Shenzhou 6

Topic: Astronomy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 15 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 15 min

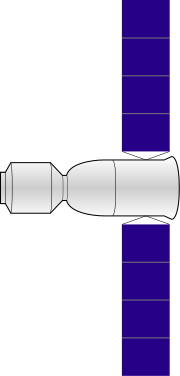

Diagram of the Shenzhou capsule-stack, without deployed orbit module solar cells | |

| Operator | |

|---|---|

| COSPAR ID | 2005-040A |

| SATCAT no. | 28879 |

| Mission duration | 4 days, 19 hours, 33 minutes |

| Orbits completed | 76[1] |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft type | Shenzhou |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 2 |

| Members | |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | October 12, 2005, 01:00:05.583 UTC |

| Rocket | Chang Zheng 2F |

| Launch site | Jiuquan LA-4/SLS-1 |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | October 16, 2005, 20:33 UTC |

| Landing site | Amugulang pasture, Hongger Township Siziwang Banner, Inner Mongolia[vague] |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

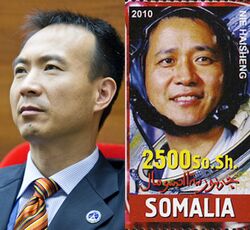

(L-R) Jùnlóng and Hǎishèng Shenzhou missions | |

Shenzhou 6 (Chinese: 神舟六号; pinyin: Shénzhōu lìuhào) was the second human spaceflight of the Chinese space program, launched on October 12, 2005, on a Long March 2F rocket from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center. The Shenzhou spacecraft carried a crew of Fèi Jùnlóng (费俊龙) and Niè Hǎishèng (聂海胜) for five days in low Earth orbit. It launched three days before the second anniversary of China's first human spaceflight, Shenzhou 5.

The crew were able to change out of their new lighter space suits, conduct scientific experiments, and enter the orbital module for the first time, giving them access to toilet facilities. The exact activities of the crew were kept secret but were thought by some to include military reconnaissance, however this is likely untrue given that similar experiments in the United States of America and USSR determined that humans in space are not suited for military reconnaissance.[2] It landed in the Siziwang Banner of Inner Mongolia on October 16, 2005, the same site as the previous crewed and uncrewed Shenzhou flights.

Crew

| Position | Crew Member | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander (指挥长) |

Fei Junlong First spaceflight | |

| Flight Engineer (操作手) |

Nie Haisheng First spaceflight | |

Backup Team 1

| Position | Crew Member | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander (指挥长) |

Liu Boming | |

| Flight Engineer (操作手) |

Jing Haipeng | |

Back-up Team 2

| Position | Crew Member | |

|---|---|---|

| Commander (指挥长) |

Zhai Zhigang | |

| Flight Engineer (操作手) |

Wu Jie | |

Crew notes

This is the first spaceflight for both crew members. The crew was introduced to the Chinese public and international media about five hours before the launch. Niè Hǎishèng celebrated his 41st birthday in space.

Huang Chunping, the chief designer of the Long March 2F rocket, was quoted in the Beijing Times as saying the crew members who would fly the mission were selected from a pool of three pairs. Five pairs of astronauts trained for the flight and about one month before launch the two pairs with the lowest performance were dropped.[3] The Ta Kung Pao newspaper had reported that Zhai Zhigang and Nie Haisheng were the leading pair, after having been in the final group of three for Shenzhou 5.

Mission highlights

Launch

The crew arrived at the spacecraft about 2 hours and 45 minutes before the launch and the hatch closed 30 minutes after their arrival. At 01:00:05.583 UTC on October 12 Shenzhou 6 lifted off from the launch pad at Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center. The launch phase was reported to be normal with the escape rocket separating 120 seconds after launch when the rocket was travelling 1,300 m/s (4300 ft/s). Sixteen seconds later the four booster rockets separated at an altitude of 52 km (32 mi). The payload fairing and first stage detached 200 seconds after launch. The second stage burned for a further 383 seconds and the spacecraft separated from the rocket 200 km (120 mi) above the Yellow Sea. The spacecraft then used its own propulsion system to place it into a 211 km by 345 km (131 by 214 statute miles) orbit, with an inclination of 42.4 degrees, about 21 minutes after launch.[4] At 01:39 UTC Chen Bingde, the Chief Commander of the Chinese space program, announced the launch was successful. The crew ate their first meal in space at 03:11 UTC.

Before the flight, the launch time had been the object of speculation by the Chinese media. For several months before the planned launch its time was only given as mid-October, or even late-September. Then on September 23 it was reported by the Hong Kong-based news agency China News Service that the launch was tentatively scheduled for 03:00 UTC on October 13. This launch time was confirmed two weeks later by Jiang Jingshan, a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering. But then on October 10 an official from the technical department of the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center said the launch was then scheduled for 01:00 UTC on October 12. This new launch time could have been designed to dodge the cold weather which had been forecast to hit the area.[5] Assembly of the rocket was reported complete on September 26.[6] On October 4, the Shenzhou 6 spacecraft was attached to the CZ-2F rocket, also known as Shenjian.[7]

Unlike the uncrewed Shenzhou flights, Shenzhou 5 and 6 were launched during daylight hours to provide greater safety in case of abort. The launch was televised live with China Central Television selling advertising for RMB¥2.56 million (United States dollar 316,000) for five seconds, to RMB¥8.56 million (US$1 million) for 30 seconds.[8] A video camera had been added to the rocket and images of it were broadcast during the ascent and the separation of the Shenzhou spacecraft.

Shortly after launch, recovery crews began searching a region from the Badain Jaran Desert in Inner Mongolia to Shaanxi for the launch escape tower, booster rockets, first stage and payload fairing. Of particular interest was the "black box" of the rocket, which contained telemetry that may not have been downlinked during the launch phase. It was found 45 minutes after launch somewhere near Otog Banner. It was first sighted by a herdswoman, Lian Hua, about 1.5 km from her home. Other wreckage from the launch was found and destroyed at its impact location or brought back to Jiuquan.[9]

General Secretary and President Hu Jintao was present at the Beijing Aerospace Control Center to watch the launch. Premier Wen Jiabao was present at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center.

Five days in orbit

The first of several orbit changing maneuvers happened as planned at 07:54:45, with a 63-second burn to circularize the orbit. Based on United States Space Command orbital elements, it was in a 332 by 336 km (206 by 209 statute miles) orbit. After about an hour and a half, the hatch between the re-entry and orbital modules was opened and, for the first time, crew were able to enter the second living compartment of the Shenzhou spacecraft. Fèi Jùnlóng was the first to enter, while Niè Hǎishèng remained in the reentry module. They would swap positions about three hours later.

At 13:32 UTC, Niè and Fèi had a seven-minute conversation with their wives and children who were in Mission Control.[10] Niè's daughter sang "Happy Birthday to You", as his birthday is October 13.

The activities of the crew were not fully revealed by the Chinese. Only vague references to experiments were made, though some were made public. One experiment involved the crew testing the reaction of the spacecraft to movement within the orbital and reentry modules. They moved between the modules, opening and closing the hatches and operating equipment with "more strength" than normally required.[11]

A second orbital maneuver occurred at 21:56 on October 13. It raised the orbit that had been lowered due to atmospheric drag, and lasted 6.5 seconds.

On October 15, Niè and Fèi had a two-minute conversation with General Secretary and President Hu Jintao, beginning at 08:29. During the conversation, Hu told them "The motherland and people are proud of you. I hope you will successfully complete your task by carrying out the mission calmly and carefully and have a triumphant return".[12]

Re-entry and landing

The re-entry process began at 19:44 on October 16 when the orbital module separated as planned from the rest of the spacecraft. Unlike with the Soyuz spacecraft, this is done before the re-entry burn, allowing the orbital module to stay in orbit for extended months-long missions or to act as a docking target for later flights. The orbital module fired its engines twice on October 19 to give it a circular orbit with a height of 355 km (221 mi).[13]

One minute after this separation, the engines on the service module ignited over the coast of West Africa to slow the spacecraft. At 20:07, the re-entry module separated and five minutes later the re-entry proper began, as the Shenzhou capsule entered the top of the atmosphere, over China. The communications blackout that occurs during re-entry started at 20:16 and two minutes later radio communication was regained with the spacecraft. The main parachute opened and the capsule began to slowly descend to a landing on the Inner Mongolia northern grasslands at 4:33 a.m. local time (20:33 UTC).[14] The capsule landed approximately 1 km (about 1000 yards) from its planned target.[15]

About half an hour after landing, the recovery forces had the hatch of the spacecraft open and first Fèi, and then Niè emerged. Hou Ying, chief designer of the landing site system, said the recovery was improved over that of Shenzhou 5.[16] After medical check-ups and a light meal the astronauts were put on a special plane bound for Beijing, where they were placed into medical isolation for the following two weeks.[17] At 21:46, Chen Bingde had declared the entire mission to be a success.

The capsule was returned to Beijing by train and handed over to China Research Institute of Space Technology at Changping railway station.[18]

The orbital module continued to orbit the Earth, gathering more information from experiments on board. The module also gave Chinese mission controllers experience at long-duration spaceflights. After 2,920 orbits of the Earth, its active mission ended on April 15, 2006. It is still in orbit, and will reenter when its orbit sufficiently decays.[19]

There were two planned landing sites for the mission. The primary site was the banner of Siziwang in Inner Mongolia. The secondary site was at the Jiuquan launch site. In addition, there were recovery forces at Yinchuan, Yulin and Handan. It is also possible for the Shenzhou spacecraft to splashdown in the ocean should the need arise, with further recovery crews in the Yellow Sea, the East China Sea and the Pacific Ocean.[20]

Some Chinese diplomats are trained and equipped for any emergency landing at sites that are not on Chinese territory. Zhang Shuting, chief designer of the emergency and rescue system, has said that emergency landing sites have been identified in Australia, Southwest Asia, North Africa, Western Europe, the United States and South America.[21] The diplomatic mission nearest to the landing site will be given the task to head any rescue mission if necessary. The Chinese government had advised Australia that emergency landing sites have been identified in New South Wales, Queensland, the Northern Territory and Western Australia. Emergency Management Australia, the Australian government agency that co-ordinates the response to major contingencies, has said they are ready to deal with any emergencies that arise during spaceflights.[22] However, the return module is designed to allow access from the outside only to those with a special key. A copy of this key has not been made available to Australian officials, but it was reported that an unnamed Chinese military attaché at the Chinese embassy in Canberra had one.[23]

Project management

As with previous Shenzhou series, Chinese military is heavily involved, and in official Chinese documents, project managers are referred as project commanders instead:

- General project manager / commander: Chen Bingde

- 1st vice general project manager / commander: Lieutenant General Hu Shixiang (胡世祥), vice director-general of General Armaments Department

- Vice general project manager / commander: Zhang Qingwei

- Vice general project manager / commander: Jiang Mianheng

- Vice general project manager / commander: Sun Laiyan

- General engineer: Wang Yongzhi

- Vice general engineer: Zhou Jianping (周建平), who was born in Wangcheng County, 1957. He obtained his M.S. from Dalian University of Technology, his Ph.D. from National University of Defense Technology, where he became a professor. From 1993 thru 1995, he studies in the United States. He would later become the general engineer for Shenzhou 7.

- Director of Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center: Major General Zhang Yulin (张育林)

- Vice director of Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center: Major General Cui Jijun (崔吉俊)

- General engineer of ground support at Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center: Wang Jingan (王金安)

Upgrades

The Chinese space officials have said that the Long March 2F rocket featured a "fire security system" on the escape tower. Speculation on what this means ranges from better fail-safes to stop accidental firings, to the addition of a fire extinguisher. The Wen Wei Po newspaper have reported that the rocket appeared the same as that used for Shenzhou 5 except that a "transition segment" was visible at the top of the Shenzhou 6 stack, attached to one end of the orbital module.

China Aerospace Science and Technology, the major manufacturer of both the Shenzhou spacecraft and the Long March rocket have said that although the flight featured a second astronaut and was much longer than Shenzhou 5, the rocket and spacecraft did not weigh much more due to optimisation of its systems.[24] Only 200 kg (about 440 lb) more was needed for the second astronaut.[25] Among the amenities on board for the crew was hot food, sleeping bags and essential sanitary equipment. The sleeping bag was hooked to a wall of the orbital module and the crew had alternating sleep periods.[26] The shock absorbers in the crew seats were redesigned so as to provide more safety to the crew in case the braking rockets fail to fire just before touchdown. The flight telemetry recorder on the spacecraft had its memory increased to about 1 gigabyte, and the read/write speed was now 10 times as fast as the computers carried on previous flights.[27] It was also about half the size of that carried on Shenzhou 5. Overall, 95% of the Shenzhou 6 space capsule is indigenously designed/produced in China, the highest rate in comparison to the previous ones.

The menu included pineapple-filled mooncakes, green vegetables, braised bamboo shoots, rice, and bean congee. In total there was 40 kg (about 88 lb) of food on board.[28] A somewhat strange aspect of the mission reported in the Chinese press was the fixation on the purity of drinking water for the astronauts, where it was claimed that their water reportedly comes from a mine 1.7 km (1.1 mi) underground and was disinfected with an electrolytic silver solution. It has thus been said by the press that they are drinking the "purest water in China".[29]

It had been reported that, on Shenzhou 5, astronaut Yang Liwei suffered from a "minor heartache" after his launch. It is thought that this refers to space adaptation syndrome experienced by about one third of astronauts during the first few days of a spaceflight. The People's Daily said that the interior design of the spacecraft has been changed to hopefully lessen the likelihood of nausea and other symptoms.

Experiments

It was announced in July 2005 that Shenzhou 6 would carry one experiment involving the sperm of pigs from Rongchang County, Chongqing.[30] But on October 11 it was revealed by Liu Luxiang, director of the Centre for Space Breeding at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, that there were no plans for animal or plant seeds on the flight. He said the focus of Shenzhou 6 was the physical reactions of the crew to the space environment.[31] This was seemingly contradicted a year and a half after the flight when sweet potatoes started being sold for Valentine's Day that had been grown from seeds reportedly taken on the flight.[32]

Morris Jones who writes for SpaceDaily.com has speculated that the lack of any other announced experiments suggested that the mission could be oriented more toward the military. The crew could have operated a large surveillance film camera, supplementing the uncrewed recoverable satellite program.

Tracking

There are 20 land-based tracking stations in the Chinese space telemetry network. These are supplemented by four Yuanwang-series tracking ships. The Beijing Aerospace Command and Control Center global map showed their positions to be:[33]

- Yuanwang 1 in the Yellow Sea

- Yuanwang 2 about 1500 km (about 900 statute miles) southwest of French Polynesia

- Yuanwang 3 off the Namibian coast

- Yuanwang 4 off the coast of Western Australia in the Indian Ocean

Only one other land-based tracking station is outside China — at Swakopmund in Namibia.

Shortly after the Shenzhou 5 flight in 2003, the Pacific nation of Kiribati established diplomatic ties with the Republic of China (Taiwan), leading the People's Republic of China (PRC) to cut off diplomatic ties under its One-China policy.[34] Following this, the PRC has dismantled a tracking station that had been built on Tarawa, the capital island of Kiribati, to track spaceflights.[35]

International reaction

Statements from the Greater China area

The Central Government of the People's Republic of China – Premier Wen Jiabao reiterated China's policy for peaceful use of space and hailed the successful launch.[36]

The Central Government of the People's Republic of China – Premier Wen Jiabao reiterated China's policy for peaceful use of space and hailed the successful launch.[36] Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China – Chief Executive Donald Tsang congratulated the motherland on the successful launch.[37]

Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China – Chief Executive Donald Tsang congratulated the motherland on the successful launch.[37] The Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) of the Republic of China (Taiwan) – Lien Chan, honorary party chairman, said the "great scientific achievement is worthy of joy and pride".[38]

The Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party) of the Republic of China (Taiwan) – Lien Chan, honorary party chairman, said the "great scientific achievement is worthy of joy and pride".[38]

Foreign countries and international organizations

Australia – Foreign Minister Alexander Downer stated that "Australia warmly welcomes the success of China's mission into space".

Australia – Foreign Minister Alexander Downer stated that "Australia warmly welcomes the success of China's mission into space". Bulgaria – President Georgi Parvanov sent a letter to Hu Jintao congratulating the PRC on the "remarkable achievements in peaceful exploitation of the outer space".[39]

Bulgaria – President Georgi Parvanov sent a letter to Hu Jintao congratulating the PRC on the "remarkable achievements in peaceful exploitation of the outer space".[39] Cameroon – Ndoumba Eloungou Nestor, secretary of Cameroon's External Relations Ministry said the launch encouraged a vast number of developing countries.[40]

Cameroon – Ndoumba Eloungou Nestor, secretary of Cameroon's External Relations Ministry said the launch encouraged a vast number of developing countries.[40] France – President Jacques Chirac congratulated the successful return of the spacecraft.[41]

France – President Jacques Chirac congratulated the successful return of the spacecraft.[41] Japan – Chief Cabinet Secretary Hiroyuki Hosoda hoped the crew would have a safe return and said development in China of crewed spacecraft was not a "military threat".[42]

Japan – Chief Cabinet Secretary Hiroyuki Hosoda hoped the crew would have a safe return and said development in China of crewed spacecraft was not a "military threat".[42] Russia – Nikolai Moiseyev, deputy head of the Russian Federal Space Agency said "another power has joined the space club" and that Russia looked "forward to further cooperation with them in all areas".[43]

Russia – Nikolai Moiseyev, deputy head of the Russian Federal Space Agency said "another power has joined the space club" and that Russia looked "forward to further cooperation with them in all areas".[43] Singapore – President S.R. Nathan sent a congratulatory letter to President Hu Jintao saying it was a proud moment for all Chinese.[44]

Singapore – President S.R. Nathan sent a congratulatory letter to President Hu Jintao saying it was a proud moment for all Chinese.[44] Uganda – Minister of State for Information Nsaba Buturo said the launch will stop the domination of outer space by a few countries in the world.[45]

Uganda – Minister of State for Information Nsaba Buturo said the launch will stop the domination of outer space by a few countries in the world.[45] United Nations – A spokesperson for United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, said that Annan extended his "warm congratulations...on the safe and successful completion of its second mission into space".[46]

United Nations – A spokesperson for United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan, said that Annan extended his "warm congratulations...on the safe and successful completion of its second mission into space".[46] United States – Deputy State Department spokesman Adam Ereli congratulated China on the launch of its second crewed spacecraft, and applauded its success as only the third nation with this capability.[47]

United States – Deputy State Department spokesman Adam Ereli congratulated China on the launch of its second crewed spacecraft, and applauded its success as only the third nation with this capability.[47]

NASA – Administrator Michael Griffin congratulated China on its launch and wished them a safe journey.[48] In his remarks, he noted "China, once again, has demonstrated that it is among the elite number of countries capable of human space flight. We wish them well on their mission, and we look forward to the safe return of their astronauts."[49]

NASA – Administrator Michael Griffin congratulated China on its launch and wished them a safe journey.[48] In his remarks, he noted "China, once again, has demonstrated that it is among the elite number of countries capable of human space flight. We wish them well on their mission, and we look forward to the safe return of their astronauts."[49]

European Space Agency – European astronaut Frank De Winne wished the crew a smooth journey. He commented on the fact that Europe had yet to create its own independent crewed spacecraft.[50]

European Space Agency – European astronaut Frank De Winne wished the crew a smooth journey. He commented on the fact that Europe had yet to create its own independent crewed spacecraft.[50]

See also

- Chinese space program

- Tiangong program

- Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center

- Long March 2F Rocket

References

- ↑ "Shenzhou VI" (in en). Archived from the original on 2020-10-01. https://web.archive.org/web/20201001192955/http://en.cmse.gov.cn/missions/shenzhouvi/. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ↑ Mark Wade. "Shenzhou 6". Encyclopedia Astronautica. http://www.astronautix.com/flights/shezhou6.htm. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ↑ "Astronauts In Training For Second Manned Spaceflight". Xinhua News Agency. March 7, 2005. http://www.spacedaily.com/news/china-05z.html.

- ↑ "Nerve hub of China's space programme". China Daily. 2005-10-13. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-10/13/content_484586.htm.

- ↑ "Cold weather may force China to postpone manned space mission: report". Agence France-Presse. 2005-10-07.

- ↑ "Shenzhou-6 spaceship finishes assembling". People's Daily. 2005-09-26. http://english.people.com.cn/200509/26/eng20050926_210970.html.

- ↑ "神六飞船与神箭在酒泉发射中心完美对接". Sina.com. 2005-10-06. http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2005-10-06/03317101389s.shtml.

- ↑ "State TV begins selling ads for China's manned space flight". Agence France-Presse. 2005-09-20. http://www.sinodaily.com/2005/050920101933.sj5y9qa3.html.

- ↑ "Rocket "black box" found in Inner Mongolia". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/12/content_3608596.htm.

- ↑ "Chinese Astronaut Calls Family from Space". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-15. http://www.china.org.cn/english/TRsummer/77436.htm.

- ↑ "Astronauts test the spacecraft". Shanghai Daily. 2005-10-13. https://www.google.com/search?q=cache:ZCpwSP6DZU8J:www.shanghaidaily.com/art/2005/10/13/202008/Astronauts_test_the_spacecraft.htm+Astronauts_test_the_spacecraft&hl=en&gl=nz.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Chinese President Praises Shenzhou 6 Crew". Space.com. 2005-10-15. http://www.space.com/missionlaunches/051015_shenzhou6_day4.html.

- ↑ "Shenzhou 6 Orbital Module Reaches Higher Orbit". Space.com. 2005-10-21. http://www.space.com/missionlaunches/051021_shenzhou6_orbital_module.html.

- ↑ "Chinese astronauts return from space". Spaceflight Now. October 16, 2005. http://www.spaceflightnow.com/news/n0510/16shenzhou6/.

- ↑ "Shenzhou-6 Landed Successfully". China Radio International. 2005-10-17. http://en.chinabroadcast.cn/2238/2005-10-17/118@277025.htm.

- ↑ "Shenzhou-6's recovery extremely satisfactory". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-17. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/17/content_3623154.htm.

- ↑ "Astronauts in medical isolation". China Central Television. 2005-10-18. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/18/content_3638323.htm.

- ↑ "Shenzhou-6 re-entry capsule handed over to developer". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-18. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/18/content_3642275.htm.

- ↑ "Orbiting Chinese Space Capsule Completes Mission". Agence France-Presse. 2006-04-15. http://www.spacedaily.com/reports/Orbiting_Chinese_Space_Capsule_Completes_Mission.html.

- ↑ "Landing field system operating after Shenzhou-6 lifts off". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/12/content_3608775.htm.

- ↑ "Shenzhou-6 able to return in emergency at any time: chief designer". People's Daily. 2005-10-14. http://english.people.com.cn/200510/14/eng20051014_214371.html.

- ↑ "Crisis? Crash near Oz". Sydney Morning Herald. 2005-10-12. http://www.smh.com.au/news/national/in-case-of-cosmic-crisis-just-crash-near-australia/2005/10/11/1128796528933.html.

- ↑ "Secrets for Chinese eyes only if space capsule falls to earth". The Australian. 2005-10-15. http://www.csuchen.de/news/viewarticle.php?id=116153.

- ↑ "Space mission set: two to orbit in Shenzhou-VI". China Daily. 2005-01-21. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-01/21/content_410892.htm.

- ↑ "China Prepares for Shenzhou VI Space Flight 13 October – Agency". Zhongguo Tongxun She. 2005-09-24. http://www.redorbit.com/news/space/250050/china_prepares_for_shenzhou_vi_space_flight_13_october_/.

- ↑ "How do astronauts eat, sleep in spaceship?". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/12/content_3609268.htm.

- ↑ "The look of Shenzhou-VI manned spaceship". People's Daily. 2005-10-13. http://english.people.com.cn/200510/12/eng20051012_213999.html.

- ↑ "Fly me to the mooncakes". Reuters. 2005-10-12. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/english/doc/2005-10/12/content_484381.htm.

- ↑ "Astronauts aboard Shenzhou-6 drink "purest" water from deep underground". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://english.people.com.cn/200510/12/eng20051012_213941.html.

- ↑ "China Space Flight to Test Cosmic Radiation on Pig Sperm". Deutsche Presse-Agentur. 2005-07-18. http://indcoup.blogspot.com/2005/07/pigs-in-space.html. [|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Official: Shenzhou VI not to carry plant seeds". China Daily. 2005-10-11. http://english.people.com.cn/200510/11/eng20051011_213771.html.

- ↑ "Lift-off for Chinese space potato". BBC News. 2007-02-12. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/6353403.stm.

- ↑ "Beijing Aerospace Command, Control Center". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/12/content_3607832.htm.

- ↑ "Diplomatic dispute won't hurt space mission". China Daily. 2003-12-01. http://www2.chinadaily.com.cn/en/doc/2003-12/01/content_286035.htm.

- ↑ "South Tarawa Island, Republic of Kiribati". http://www.globalsecurity.org/space/world/china/kiribati.htm.

- ↑ "Premier Wen Jiabao hails successful launch of spacecraft Shenzhou-6". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://english.people.com.cn/200510/12/eng20051012_213934.html.

- ↑ "HK CE congratulates launch of spacecraft Shenzhou-6". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/12/content_3608304.htm.

- ↑ "Lien Chan hails successful re-entry of Shenzhou-6". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-18. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/18/content_3638064.htm.

- ↑ "Bulgaria congratulates China on successful crewed space mission". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-18. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/18/content_3640464.htm.

- ↑ "Various countries congratulate China on 2nd crewed space mission". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-13. http://english.people.com.cn/200510/13/eng20051013_214166.html.

- ↑ "Chirac congratulates China on spaceship return". China Radio International. 2005-10-13. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/17/content_3624324.htm.

- ↑ "Japan hails China's successful launch of crewed Shenzhou-6". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/12/content_3610439.htm.

- ↑ "Russia hails China space launch". Agence France-Presse. 2005-10-12. http://www.spacedaily.com/2005/051012070219.d8c2dzqk.html.

- ↑ "Singapore hails China's successful launch of spacecraft". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/12/content_3609569.htm.

- ↑ "Uganda welcomes China's new start of access to space". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/13/content_3613110.htm.

- ↑ "Annan congratulates China on its second space mission". United Nations. 2005-10-17. https://www.un.org/apps/news/story.asp?NewsID=16265&Cr=china&Cr1=.

- ↑ "US hails China's second crewed space mission". Agence France-Presse. 2005-10-12. http://www.spacedaily.com/2005/051012202502.l5dk6tvx.html.

- ↑ "NASA Administrator Marks China's Second Human Space Flight". NASA. 2005-10-12. http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2005/oct/HQ_05343_Griffin_China_statement.html.

- ↑ "NASA Administrator Marks China's Second Human Space Flight". nasa.gov. http://www.nasa.gov/home/hqnews/2005/oct/HQ_05343_Griffin_China_statement.html.

- ↑ "European astronaut wishes China success in 2nd crewed space mission". Xinhua News Agency. 2005-10-12. http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2005-10/12/content_3608178.htm.

- Jones, Morris (March 7, 2005). "Media Rollout For Shenzhou 6". SpaceDaily. http://www.spacedaily.com/news/china-05x.html.

- Jones, Morris (September 27, 2005). "Media Weighing Up Shenzhou 6". SpaceDaily. http://www.spacedaily.com/news/china-05zzzzzzzr.html.

- "Shenzhou 6 Mission In Final Preparation For Possible Launch On October 13". SpaceDaily.com. October 6, 2005. http://spacedaily.com/news/china-05zzzzzzzzd.html.

- "Yang Liwei Says Shenzhou 6 Astronauts Capable of New Space Mission". Xinhua News Agency. October 11, 2005. http://en.chinabroadcast.cn/2238/2005-10-11/38@276204.htm.

External links

- Xinhua News Agency coverage

- Dragon Space – China's civilian, military and manned space programs

- Shenzhou 6 – China's Second Manned Space Mission

- Spacefacts data about Shenzhou 6

- Shenzhou 6 training photographs. From Xinmin Evening News (in Chinese)

- "Getting ready for space flight tomorrow—"Heroic astronaut team" makes preparations for manned spaceflight", PLA Daily. Accessed July 24, 2005

- "Satellite Spots China’s Manned Rocket", Space.com article about IKONOS satellite image of Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center

|

KSF

KSF