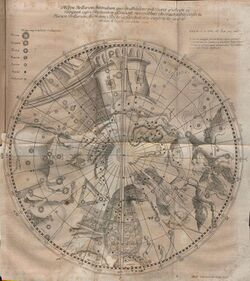

Southern celestial hemisphere

Topic: Astronomy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 3 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 3 min

The southern celestial hemisphere, also called the Southern Sky, is the southern half of the celestial sphere; that is, it lies south of the celestial equator. This arbitrary sphere, on which seemingly fixed stars form constellations, appears to rotate westward around a polar axis due to Earth's rotation.

At any given time, the entire Southern Sky is visible from the geographic South Pole, while less of this hemisphere is visible the further north the observer is located. The northern counterpart is the northern celestial hemisphere.

Astronomy

In the context of astronomical discussions or writing about celestial mapping, it may also simply then be referred to as the Southern Hemisphere.

For the purpose of celestial mapping, the sky is considered by astronomers as the inside of a sphere divided in two halves by the celestial equator.[according to whom?] The Southern Sky or Southern Hemisphere is, therefore, that half of the celestial sphere that is south of the celestial equator. Even if this one is the ideal projection of the terrestrial equatorial onto the imaginary celestial sphere, the Northern and Southern celestial hemispheres must not be confused with descriptions of the terrestrial hemispheres of Earth itself.[according to whom?]

Observation

From the South Pole, in good visibility conditions, the Southern Sky features over 2,000 fixed stars that are easily visible to the naked eye, while about 20,000 to 40,000 with the aided eye.[citation needed][dubious ] In large cities, about 300 to 500 stars can be seen depending on the extent of light and air pollution.[citation needed] The farther north, the fewer are visible to the observer.[citation needed]

The brightest stars are all larger than the Sun.[dubious ] Sirius in the constellation of Canis Major has the brightest apparent magnitude of –1.46; it has a radius twice that of the Sun and is 8.6 light-years away. Canopus and the next fixed star Toliman (α Centauri), 4.2 light-years away, are also located in the Southern Sky, having declinations around –60° – too close to the south celestial pole that neither are visible from Central Europe.[1]

History

The Southern Sky was first substantially charted by English astronomer Edmond Halley,[2] and published by him in 1679.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ David Ellyard, Wil Tirion: The Southern Sky Guide. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge 2009, ISBN 978-0-521-71405-1

- ↑ "Edmond Halley (1656–1742)". 2014. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/halley_edmond.shtml.

- ↑ Kanas, Nick (2012). Star Maps: History, Artistry, and Cartography (2nd ed.). Chickester, U.K.: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-0917-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=bae3LP4tfP4C&pg=PA123.

KSF

KSF