Thermodynamics of the universe

Topic: Astronomy

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

| Part of a series on |

| Physical cosmology |

|---|

|

The thermodynamics of the universe is dictated by which form of energy dominates it - relativistic particles which are referred to as radiation, or non-relativistic particles which are referred to as matter. The former are particles whose rest mass is zero or negligible compared to their energy, and therefore move at the speed of light or very close to it; the latter are particles whose kinetic energy is much lower than their rest mass and therefore move much slower than the speed of light. The intermediate case is not treated well analytically.

Energy density in the expanding universe

If the universe is expanding adiabatically then it will satisfy the first law of thermodynamics:

where is the total heat which is assumed to be constant, is the internal energy of the matter and radiation in the universe, is the pressure and the volume.

One then finds an equation for the energy density , and so

where in the last equality we used the fact that the total volume of the universe is proportional to , being the scale factor of the universe.

In fact this is a wrong derivation because it assumes that the pressure is doing work as increases. However, in the average universe, the pressure is the same everywhere, and thus there is no under-pressure region against which the pressure can do work. The above equation can be directly obtained from the equations of motion governing the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric: by dividing the equation above with and identifying (the energy density), we get one of the FLRW equations of motions.

In the comoving coordinates, is equal to the mass density . For radiation, whereas for matter and the pressure can be neglected. Thus we get:

For radiation thus is proportional to

For matter thus is proportional to

This can be understood as follows: For matter, the energy density is equal (in our approximation) to the rest mass density. This is inversely proportional to the volume, and is therefore proportional to . For radiation, the energy density depends on the temperature as well, and is therefore proportional to . As the universe expands it cools down, so depends on as well. In fact, since the energy of a relativistic particle is inversely proportional to its wavelength, which is proportional to , the energy density of the radiation must be proportional to .

From this discussion it is also obvious that the temperature of radiation is inversely proportional to the scale factor .

Rate of expansion of the universe

Plugging this information to the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker equations of motion and neglecting both the cosmological constant and the curvature parameter , which is justified for the early universe (), one gets the following equation:

is the energy density, and one finds the following behavior:

- In a radiation-dominated universe:

- In a matter-dominated universe:

One can further show that the universe was radiation-dominated as long as the energy density was of the order of 10 eV to the fourth, or higher. Since the energy density keeps going down, this was no longer true when the universe was 70,000 years old, when it became matter dominant.

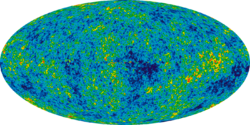

In the universe today, matter is mainly in forms of galaxies and dark matter, while the radiation is the cosmic microwave background radiation, the cosmic neutrino background (if the neutrino rest mass is high enough then the latter is formally matter), and finally, mostly in the form of dark energy.

Dark energy and cosmic inflation

Dark energy is a hypothetical form of energy that permeates all of space and its negative pressure coincides with an acceleration in the expansion of the universe. Positive pressure coincides with a deceleration as does the gravity of energy and mass. There is no known cause and effect in fundamental physics, so it is not assumed the pressures or gravity "cause" a reduction or acceleration in the expansion of the universe, nor vice versa. For example, the energy in the gravitional field of the universe that coincides with its expansion is equal and opposite to the mass energy of the universe and it is not assumed (and the equations do not indicate) that the expansion created the positive mass energy and negative gravitational energy, nor vice versa.

According to the equation above,

Thus the more negative the pressure is, the less the energy density reduces as the universe expands. In other words, Dark energy dilutes less than any other form of energy, and will therefore eventually dominate the universe, as all other energy densities gets diluted faster with the expansion of the universe.

In fact, if the dark energy is created by a cosmological constant or a constant scalar field, then its pressure is minus its energy density , and therefore its energy density remains constant (as is expected by definition).

Dark energy is usually assumed to be the Casimir energy of the vacuum, with possible contributions from the energy density of scalar fields which has a non-zero value at the vacuum. It may be that this field can decay at some time in the distant future, leading to a new vacuum state, different than the one we are living in. This is a phase transition, where the dark energy is reduced and huge amounts of energy in conventional forms (i.e. particles) are produced.

Such a series of events is in fact thought to have already occurred in the early universe, where first a cosmological constant much larger than the present one came to dominate the universe, bringing about cosmic inflation. At the end of this epoch, a phase transition occurred where the cosmological constant was reduced to its present value and huge amounts of energy were produced, from which all the radiation and matter of the early universe came about.

See also

- Physical cosmology

- Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker metric

- Dark energy

- Cosmic inflation

- Thermodynamics

- First law of thermodynamics

KSF

KSF