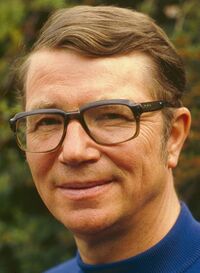

Colin Wilson

Topic: Biography

From HandWiki - Reading time: 16 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 16 min

Colin Wilson | |

|---|---|

Wilson in Cornwall, 1984 | |

| Born | Colin Henry Wilson Leicester, Leicestershire, England |

| Died | 5 December 2013 (aged 82) St Austell, Cornwall, England |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Nationality | British |

| Period | Active: 1956–2013, 20th century |

| Genre |

|

| Literary movement | Angry young men |

| Notable works |

|

Colin Henry Wilson (26 June 1931 – 5 December 2013) was an English existentialist philosopher-novelist. He also wrote widely on true crime, mysticism and the paranormal,[1] eventually writing more than a hundred books.[2] Wilson called his philosophy "new existentialism" or "phenomenological existentialism",[3] and maintained his life work was "that of a philosopher, and (his) purpose to create a new and optimistic existentialism".[4]

Early life

Wilson was born on 26 June 1931 in Leicester,[5] the first child of Arthur and Annetta Wilson. His father worked in a shoe factory.[6] At the age of eleven he attended Gateway Secondary Technical School, where his interest in science began to blossom. By the age of 14 he had compiled a multi-volume work of essays covering many aspects of science entitled A Manual of General Science. But by the time he left school at sixteen, his interests were already switching to literature. His discovery of George Bernard Shaw's work, particularly Man and Superman, was a landmark. He started to write stories, plays, and essays in earnest – a long "sequel" to Man and Superman made him consider himself to be 'Shaw's natural successor.' After two unfulfilling jobs – one as a laboratory assistant at his old school – he drifted into the Civil Service, but found little to occupy his time.

In the autumn of 1949, he was conscripted into the Royal Air Force but soon found himself clashing with authority, eventually feigning homosexuality in order to be dismissed. Upon leaving he took up a succession of menial jobs, spent some time wandering around Europe, and finally returned to Leicester in 1951. There he married his first wife, (Dorothy) Betty Troop, and moved to London, where a son, Roderick Gerard, was born. He later wrote a semi-autobiograpical novel, Adrift in Soho, that was based on his time in London. But the marriage rapidly disintegrated as he drifted in and out of several jobs. During this traumatic period, Wilson was continually working and reworking the novel that was eventually published as Ritual in the Dark (1960).[7] He also met three young writers who became close friends – Bill Hopkins, Stuart Holroyd and Laura Del-Rivo.[8] Another trip to Europe followed, and he spent some time in Paris attempting to sell magazine subscriptions. Returning to Leicester again, he met Joy Stewart – later to become his second wife and mother of their three children – who accompanied him to London. There he continued to work on Ritual in the Dark, receiving some advice from Angus Wilson (no relation) – then deputy superintendent of the British Museum's Reading Room – and slept rough (in a sleeping bag) on Hampstead Heath to save money.[9]

On Christmas Day, 1954, alone in his room, he sat down on his bed and began to write in his journal. He described his feelings as follows:

It struck me that I was in the position of so many of my favourite characters in fiction: Dostoyevsky's Raskolnikov, Rilke's Malte Laurids Brigge, the young writer in Hamsun's Hunger: alone in my room, feeling totally cut off from the rest of society. It was not a position I relished . . . Yet an inner compulsion had forced me into this position of isolation. I began writing about it in my journal, trying to pin it down. And then, quite suddenly, I saw that I had the makings of a book. I turned to the back of my journal and wrote at the head of the page: 'Notes for a book The Outsider in Literature'

The Outsider

Gollancz published the 24-year-old Wilson's The Outsider in 1956. The work examines the role of the social "outsider" in seminal works by various key literary and cultural figures – such as Albert Camus, Jean-Paul Sartre, Ernest Hemingway, Hermann Hesse, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, William James, T. E. Lawrence, Vaslav Nijinsky and Vincent van Gogh – and discusses Wilson's perception of social alienation in their work. The book became a best-seller and helped popularise existentialism in Britain.[10] It has never been out of print and has been translated into more than thirty languages.

Career

Non-fiction writing

Wilson became associated with the "angry young men" of British literature. He contributed to Declaration, an anthology of manifestos by writers associated with the movement, and was also anthologised in a popular paperback sampler, Protest: The Beat Generation and the Angry Young Men.[11][12] Some viewed Wilson and his friends Bill Hopkins and Stuart Holroyd as a sub-group of the "Angries", more concerned with "religious values" than with liberal or socialist politics.[13] Critics on the left swiftly labelled them as fascist; commentator Kenneth Allsop called them "the law givers".[13][14] Controversially, during the 1950s Wilson expressed critical support for some of the ideas of Oswald Mosley the leader of Union Movement and after Mosley's death in December 1980, Wilson contributed articles to Mosley's former secretary Jeffrey Hamm's Lodestar magazine.[15]

The success of The Outsider notwithstanding, Wilson's second book, Religion and the Rebel (1957), was universally panned by critics although Wilson himself claimed it was a more comprehensive book than the first one. While The Outsider was focused on documenting the subject of mental strain and near-insanity, Religion and the Rebel was focused on how to expand our consciousness and transform us into visionaries. Time (magazine) magazine published a review, headlined "Scrambled Egghead", that pilloried the book.[16] Undaunted, Wilson continued to expound his positive "new" existentialism in the six philosophical books known as "The Outsider Cycle", all written within the first ten years of his literary career. These books were summarised by Introduction to the New Existentialism (1966). When the book was re-printed in 1980 as The New Existentialism, Wilson wrote: "If I have contributed anything to existentialism – or, for that matter, to twentieth century thought in general, here it is. I am willing to stand or fall by it."

In The Age of Defeat (1959) – book 3 of "The Outsider Cycle" – he bemoaned the loss of the hero in twentieth century life and literature, convinced that we were becoming embroiled in what he termed "the fallacy of insignificance". It was this theory that encouraged celebrated American psychologist Abraham Maslow to contact him in 1963. The two corresponded regularly and met on several occasions before Maslow's death in 1970. Wilson wrote a biography and assessment of Maslow's work, New Pathways in Psychology: Maslow and the Post-Freudian Revolution, based on audiotapes that Maslow had provided, which was published in 1972. Maslow's observation of "peak experiences" in his students – those sudden moments of overwhelming happiness that we all experience from time to time – provided Wilson with an important clue in his search for the mechanism that might control the Outsider's "moments of vision". Maslow, however, was convinced that peak experiences could not be induced; Colin Wilson thought otherwise and, indeed, in later books like Access to Inner Worlds (1983) and Super Consciousness (2009), suggested how they could be induced at will.

Wilson was also known for what he termed "Existential Criticism", which suggested that a work of art should not just be judged by the principles of literary criticism or theory alone but also by what it has to say, in particular about the meaning and purpose of existence. In his pioneering essay for Chicago Review (Volume 13, no. 2, 1959, pp. 152–181) he wrote:

No art can be judged by purely aesthetic standards, although a painting or a piece of music may appear to give a purely aesthetic pleasure. Aesthetic enjoyment is an intensification of the vital response, and this response forms the basis of all value judgements. The existentialist contends that all values are connected with the problems of human existence, the stature of man, the purpose of life. These values are inherent in all works of art, in addition to their aesthetic values, and are closely connected with them.

He went on to write several more essays and books on the subject. Among the latter were The Strength to Dream (1962), Eagle and Earwig (1965), Poetry and Mysticism (1970) The Craft of the Novel (1975), The Bicameral Critic (1985) and The Books in My Life (1998). He also applied existential criticism to many of the hundreds of book reviews he wrote for journals including Books & Bookmen, The Literary Review, The London Magazine, John O'London's, The Spectator and The Aylesford Review throughout his career. Some of these were gathered together in a book entitled Existential Criticism: Selected Book Reviews, published in 2009.

Meanwhile, the prolific Wilson found time to write about other subjects that interested him, even on occasion when his level of expertise might be questionable. The title of his opinionated 1964 volume on music appreciation, Brandy of the Damned, inspired by his enthusiasm for record collecting,[17] used for its title a self-deprecating reference from the onetime music critic Bernard Shaw. The full quote (from Man and Superman) is: "Hell is full of musical amateurs: music is the brandy of the damned. May not one lost soul be permitted to abstain?”

By the late 1960s Wilson had become increasingly interested in metaphysical and occult themes. In 1971, he published The Occult: A History, featuring interpretations on Aleister Crowley, George Gurdjieff, Helena Blavatsky, Kabbalah, primitive magic, Franz Mesmer, Grigori Rasputin, Daniel Dunglas Home and Paracelsus, among others. He also wrote a markedly unsympathetic biography of Crowley, Aleister Crowley: The Nature of the Beast, and has written biographies on other spiritual and psychological visionaries, including Gurdjieff, Carl Jung, Wilhelm Reich, Rudolf Steiner, and P. D. Ouspensky.

Originally, Wilson focused on the cultivation of what he called "Faculty X", which he saw as leading to an increased sense of meaning, and on abilities such as telepathy and the awareness of other energies. In his later work he suggests the possibility of life after death and the existence of spirits, which he personally analyses as an active member of the Ghost Club.

He also wrote non-fiction books on crime, ranging from encyclopedias to studies of serial killing. He had an ongoing interest in the life and times of Jack the Ripper and in sex crime in general.

Fiction

Wilson explored his ideas on human potential and consciousness in fiction, mostly detective fiction or science fiction, including several Cthulhu Mythos pieces; often writing a non-fiction work and a novel concurrently – as a way of putting his ideas into action. He wrote:

For me [fiction] is a manner of philosophizing....Philosophy may be only a shadow of the reality it tries to grasp, but the novel is altogether more satisfactory. I am almost tempted to say that no philosopher is qualified to do his job unless he is also a novelist....I would certainly exchange any of the works of Whitehead or Wittgenstein for the novels they ought to have written.[18]

Like some of his non-fiction work, many of Wilson's novels from Ritual in the Dark (1960) onwards have been concerned with the psychology of murder—especially that of serial killing. However, he has also written science fiction of a philosophical bent, including The Mind Parasites (1967), The Philosopher's Stone (1969), The Space Vampires (1976) and the four-volume Spider-World series: Spider World: The Tower (1987), Spider World: the Delta (1987), Spider World: The Magician (1992) and Spider World: Shadowland (2003); novels described by one critic as "an artistic achievement of the highest order... destined to be regarded to be one of the central products of the twentieth century imagination."[19] Wilson wrote the Spider World series in response to a suggestion made to him by Roald Dahl to 'write a novel for children.' He also said he'd 'like to be remembered as the man who wrote Spider World.’

In The Strength to Dream (1961) Wilson attacked H. P. Lovecraft as "sick" and as "a bad writer" who had "rejected reality"—but he grudgingly praised Lovecraft's story "The Shadow Out of Time" as capable science fiction. August Derleth, incensed by Wilson's treatment of Lovecraft in The Strength to Dream, then dared Wilson to write what became The Mind Parasites—to expound his philosophical ideas in the guise of fiction.[20] In the preface to The Mind Parasites, Wilson concedes that Lovecraft, "far more than Hemingway or Faulkner, or even Kafka, is a symbol of the outsider-artist in the 20th century" and asks: "what would have happened if Lovecraft had possessed a private income—enough, say, to allow him to spend his winters in Italy and his summers in Greece or Switzerland?" answering that in his [Wilson's] opinion "[h]e would undoubtedly have produced less, but what he did produce would have been highly polished, without the pulp magazine cliches that disfigure so much of his work. And he would have given free rein to his love of curious and remote erudition, so that his work would have been, in some respect, closer to that of Anatole France or the contemporary Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges".[21] Wilson also discusses Lovecraft in Order of Assassins (1972) and in the prefatory note to The Philosopher's Stone (1969). His short novel The Return of the Lloigor (1969/1974) also has roots in the Cthulhu Mythos – its central character works on the real book the Voynich manuscript, but discovers it to be a mediaeval Arabic version of the Necronomicon – as does his 2002 novel The Tomb of the Old Ones.

Adaptations

Tobe Hooper directed the film Lifeforce, an adaptation written by Dan O'Bannon based on Wilson's novel The Space Vampires.[22] After its release, Colin Wilson recalled that author John Fowles regarded the film adaptation of Fowles' own novel The Magus as the worst film adaptation of a novel ever. Wilson told Fowles there was now a worse one.[23]

A film of his 1961 novel Adrift in Soho by director Pablo Behrens was released by Burning Films in 2018.

Illness and death

After a major spinal operation in 2011,[24] Wilson suffered a stroke and lost his ability to speak.[25] He was admitted to hospital in October 2013 for pneumonia. He died on 5 December 2013 and was buried in the churchyard at Gorran Churchtown in Cornwall.[5] A memorial service for him was held at St James's Church, Piccadilly, London, on 14 October 2014.

Reception

Howard F. Dossor, author of a book about Wilson’s career, wrote appreciatively: "Wilson constitutes one of the most significant challenges to twentieth-century critics. It seems most likely that critics analysing his work in the middle of the twenty-first century, will be puzzled that his contemporaries paid such inadequate attention to him. But it is not merely for their sake that he should be examined. Critics who turn to him will find themselves involved in the central questions of our age and will be in touch with a mind that has disclosed an extraordinary resilience in addressing them."[26] Critic Nicolas Tredell agreed: "The twenty-first century may look back on Colin Wilson as one of the novelists who foresaw the future of fiction, and something, perhaps, of the future of man."[27]

Science writer Martin Gardner saw Wilson as an intelligent writer who was duped by paranormal claims. He once commented that "Colin bought it all. With unparalleled egotism and scientific ignorance he believed almost everything he read about the paranormal, no matter how outrageous." Gardner described Wilson's book The Geller Phenomenon as "the most gullible book ever written about the Israeli charlatan". Gardner concluded that Wilson had decayed into an "occult eccentric" writing books for the "lunatic fringe".[28] The psychologist Dorothy Rowe gave Wilson's book Men of Mystery a negative review and wrote that it "does nothing to advance research into the paranormal".[29] Benjamin Radford has written that Wilson had a "bias toward mystery-mongering" and that he ignored scientific and skeptical arguments on some of the topics he wrote about. Radford described Wilson's book The Mammoth Encyclopedia of the Unsolved as "riddled with errors and obfuscating omissions, betraying a bizarre disregard for accuracy".[30]

In 2016 the first full-length biography of Wilson, Beyond the Robot: The Life and Work of Colin Wilson, by Gary Lachman, appeared. It received a positive endorsement from Philip Pullman, who wrote that "Wilson was always far better and more interesting than fashionable opinion claimed, and in Lachman he has found a biographer who can respond to the whole range of his work with sympathy and understanding, in a style which, like Wilson's own, is always immensely readable." Michael Dirda in The Washington Post called Wilson a "controversial writer who explored the nature of human consciousness in dozens of books" and said that Lachman, a "leading student of the western esoteric tradition, writes with "exceptional grace, forcefulness, and clarity."[31] Brett Taylor "enjoyed" the biography, but said that "a more critical author might have written a book that argued for the subject's worth in a broader and more convincing context. Lachman displays credulity on occult matters and an admiration for Wilson's sometimes dodgy philosophy."[32]

On 1 July 2016, the First International Colin Wilson Conference took place at the University of Nottingham. A second conference took place at the same venue on 6 July 2018. The Third Conference was held in Nottingham on September 1-3, 2023 which included the premiere of the Figgis-West eight-part documentary film series Colin Wilson: his life and work. Directed and edited by Jason Figgis, the documentary is a detailed study of Wilson's life and work which includes interviews with Uri Geller, Gary Lachman,Tahir Shah, Damon Wilson, Jason Figgis, John West, Martha Rafferty and Philip Pullman.[33]

Wilson's archive is held at the Manuscripts and Special Collections Department at the University of Nottingham in the United Kingdom. It contains the entirety of his published work plus manuscripts, correspondence and journals. [34]

Bibliography

References

- ↑ "Colin Wilson, author of The Outsider, dies aged 82" BBC News, 13 December 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Gary Lachman, Beyond the Robot: The Life and Work of Colin Wilson, Penguin (2016), xiv

- ↑ Introduction to the New Existentialism (1966), p.9

- ↑ Quote from Philosophy Now, Obituary of Colin Wilson, here (link) , accessed March 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Williamson, Marcus (8 December 2013). "Colin Wilson: Author (Obituary)". The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/obituaries/colin-wilson-author-8991678.html.

- ↑ Colin Wilson, Dreaming to Some Purpose (Arrow, 2005)

- ↑ Colin Wilson's 'Ritual in the Dark' "Colin Wilson: Ritual in the Dark". http://www.londonfictions.com/colin-wilson-ritual-in-the-dark.html.

- ↑ Laura Del Rivo 'The Furnished Room' "Laura Del-Rivo: The Furnished Room". http://www.londonfictions.com/laura-del-rivo-the-furnished-room.html.

- ↑ Desert Island Discs Archive: 1976–1980

- ↑ Kenneth Allsop, The Angry Decade; A Survey of the Cultural Revolt of the Nineteen Fifties. London: Peter Owen Ltd.

- ↑ Maschler, Tom, ed (1957). Declaration. London: MacGibbon and Kee.

- ↑ Feldman, Gene and Gartneberg, Max (editors) (1958). Protest: The Beat Generation and the Angry Young Men. New York: Citadel Press.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Allsop, Kenneth (1958). The Angry Decade; A Survey of the Cultural Revolt of the Nineteen Fifties. London: Peter Owen Ltd.

- ↑ Holroyd, Stuart (1975). Contraries: A Personal Progression. London: The Bodley Head Ltd.

- ↑ Skidelsky, Robert Oswald Mosley p.503, p.511, Lodestar No.1-Winter 1985/86, No.4-Autumn/Winter 1986, No.7-Winter 1987/88, No.8-Spring 1988, No.9-Summer 1988, No.11-Spring 1989, No.12-Summer 1989

- ↑ Colin Wilson, The Angry Years Robson Books, 2007

- ↑ Eric Sams. 'Colin Wilson on Music' in The Musical Times, April 1967, p 329-330

- ↑ Voyage to a Beginning (Cecil Woolf, 1968, p. 160-1)

- ↑ Howard F Dossor: Colin Wilson: the man and his mind, Element, 1990, p. 284

- ↑ Wilson, Colin (2005). The Mind Parasites (original preface). Monkfish. p. xvii. ISBN 0974935999.

- ↑ Wilson, Colin (1975). The Mind Parasites. Oneiric Press. p. 112. https://www.amazon.com/Mind-Parasites-Colin-Wilson/dp/B000WU0PP8.

- ↑ Mitchell, Charles P. (2001). A guide to apocalyptic cinema. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 112. ISBN 9780313315275. https://books.google.com/books?id=bmmrKvOwa_IC&q=%22space+vampires%22+lifeforce&pg=PA112.

- ↑ Wilson, Colin (2005). Dreaming to Some Purpose. Monkfish. p. chapter 20. ISBN 0099471477.

- ↑ "COLIN WILSON DIES AT 82". http://www.colinwilsonworld.co.uk/Pages/News.aspx.

- ↑ "The Quietus – Anthony Reynolds Discusses Colin Wilson". http://thequietus.com/articles/09789-anthony-rey%C2%ADnolds-colin-wilson-interview.

- ↑ Howard F. Dossor Colin Wilson: the Man and His Mind (1990) Element Books, pp 318–319. ISBN 1-85230-176-7

- ↑ Nicolas Tredell Novels to Some Purpose: the fiction of Colin Wilson (2015) Paupers' Press, . ISBN 9780956866363

- ↑ Gardner, Martin (1984). Order and Surprise. Oxford University Press. pp. 361–364. ISBN 0-19-286051-8

- ↑ Rowe, Dorothy (26 January 1981). "Men of mystery". New Scientist (London): pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Radford, Benjamin (2013). "Colin Wilson: A Case Study in Mystery Mongering" . Center for Inquiry. Retrieved 16 March 2014.

- ↑ "Ufos, alien abductions, the occult: to one man, the building blocks of scholarship" Michael Dirda The Washington Post 31 August 2016.

- ↑ Taylor, Brett (2018). "Colin Wilson's Idiosyncratic Literary Legacy". Skeptical Inquirer 42 (2): 54–56.

- ↑ "Colin Wilson Conference". http://pauperspress.co.uk/conference.html.

- ↑ "Colin Wilson Archive". https://mss-cat.nottingham.ac.uk/CalmView/Overview.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&q=Related_Name_Code:NA78779.

Further reading

- Bendau, Clifford P. Colin Wilson: The Outsider and Beyond (1979), San Bernardino: Borgo Press ISBN 0-89370-229-3

- Campion, Sidney R. The Sound Barrier: a study of the ideas of Colin Wilson (2011), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-81-0

- Coulthard, Philip. The Lurker at the Indifference Threshold: Feral Phenomenology for the 21st Century (2019) Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 9780995597822

- Dalgleish, Tim The Guerilla Philosopher: Colin Wilson and Existentialism (1993), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-47-0

- Dossor, Howard F. Colin Wilson: the bicameral critic: selected shorter writings (1985), Salem: Salem House ISBN 0-88162-047-5

- Dossor, Howard F. Colin Wilson: the man and his mind (1990) Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element Books ISBN 1-85230-176-7

- Dossor, Howard F. The Philosophy of Colin Wilson: three perspectives (1996), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-58-6

- Greenwell, Tom. Chepstow Road: a literary comedy in two acts (2002) Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-78-0

- Lachman, Gary. Beyond the Robot: the life and work of Colin Wilson (2016) New York: TarcherPerigee ISBN 9780399173080

- Lachman, Gary. Two essays on Colin Wilson (1994), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-52-7

- Moorhouse, John & Newman, Paul. Colin Wilson, two essays (1988), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-11-X

- Newman, Paul. Murder as an Antidote for Boredom: the novels of Laura Del Rivo, Colin Wilson and Bill Hopkins (1996), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-57-8

- Rapatahana, Vaughan. More than the Existentialist Outsider: reflections on the work of Colin Wilson (2019), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 9780995597839

- Robertson, Vaughan. Wilson as Mystic (2001), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-74-8

- Salwak, Dale (ed). Interviews with Britain's Angry Young Men (1984) San Bernardino: Borgo Press ISBN 0-89370-259-5

- Shand, John & Lachman, Gary. Colin Wilson as Philosopher (1996), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-59-4

- Smalldon, Jeffrey. Human Nature Stained: Colin Wilson and the existential study of modern murder (1991) Nottingham: Paupers'Press ISBN 0-946650-28-4

- Spurgeon, Brad. Colin Wilson: philosopher of optimism, (2006), Manchester: Michael Butterworth ISBN 0-9552672-0-X

- Stanley, Colin An Evolutionary Leap: Colin Wilson and Psychology, (2016), London: Karnac ISBN 9781782204442

- Stanley, Colin (ed). Around the Outsider: essays presented to Colin Wilson on the occasion of his 80th birthday, (2011), Winchester: O-Books ISBN 978-1-84694-668-4

- Stanley, Colin (ed). Colin Wilson, a celebration: essays and recollections (1988), London: Cecil Woolf ISBN 0-900821-91-4

- Stanley, Colin. The Ultimate Colin Wilson Bibliography 1956–2015 (2015) Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 9780956866356

- Stanley, Colin. Colin Wilson's Existential Literary Criticism: a guide for students (2014). Nottingham: Paupers' Press. ISBN 9780956866349

- Stanley, Colin. Colin Wilson's 'Occult Trilogy': a guide for students (2013). Alresford: Axis Mundi Books. ISBN 9781846947063

- Stanley, Colin. Colin Wilson's 'Outsider Cycle': a guide for students (2009). Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-96-9

- Stanley, Colin. The Nature of Freedom' and other essays (1990), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-17-9

- Stanley, Colin (ed). Proceedings of the First International Colin Wilson Conference, University of Nottingham, July 1, 2016 (2017) Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 9781443881722

- Stanley, Colin (ed). Reflections on the work of Colin Wilson: Proceedings of the Second International Colin Wilson Conference, University of Nottingham July 6-8, 2018 (2019). Newcastle-Upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 978-1-5275-2774-4

- Stanley, Colin (ed). The Sage of Tetherdown: Recollections of Colin Wilson by his friends (2020) Nottingham: Paupers' Press. ISBN 9780995597884

- Stanley, Colin. The Writing of Colin Wilson's 'Adrift in Soho' (2016) ISBN 9780956866370

- Tredell, Nicolas. The Novels of Colin Wilson (1982) London: Vision Press ISBN 0-85478-035-1

- Tredell, Nicolas. Novels to Some Purpose: the fiction of Colin Wilson (2015) Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 9780956866363

- Trowell, Michael. Colin Wilson, the positive approach (1990), Nottingham: Paupers' Press ISBN 0-946650-25-X

- Weigel, John A. Colin Wilson (1975) Boston: Twayne Publishers ISBN 0-8057-1575-4

External links

- Colin Wilson on IMDb

- Colin Wilson Papers (2 document boxes) housed at the Eaton Collection of Science Fiction and Fantasy of the University of California, Riverside Libraries. Includes correspondence by Wilson, galley proofs and manuscripts of Wilson's works in the science fiction genre, material regarding Uri Geller, press clippings, and interviews with Wilson.

- The Colin Wilson Collection at the University of Nottingham, United Kingdom – This is Wilson's bibliographer Colin Stanley's collection of books, articles, manuscripts, letters, photographs and assorted ephemera now at the University of Nottingham. Regularly updated by Stanley. Now contains, by arrangement with the Colin Wilson Estate, about 80 original manuscripts.

- Colin Wilson Collection at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin.

- Colin Wilson World – "an appreciation" with some Wilson contributions

- The Colin Wilson Page [1996 to 2001] at Internet Archive (archived 2008-09-14)

- Abraxas– Wilson-related journal

- The Phenomenology of Excess – a multimedia Wilson site, approved by its subject

- Harry Ritchie, "Look back in wonder", The Guardian (reviews), 12 August 2006

- Entry in The Literary Encyclopedia by Colin Stanley

- Paupers' Press – including the Centre for Colin Wilson Studies

- An article by Colin Stanley on Wilson's debut novel, Ritual in the Dark at London Fictions

- Colin Stanley on Wilson's Adrift in Soho at London Fictions

- Colin Wilson at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Lyrics

Interviews

- 'Suddenly Awakened', interview for Poetic Mind.

- Audio Interview by William H. Kennedy Sphinx Radio, 9/28/08

- Interview by Gary Lachman, Fortean Times, October 2004

- Colin Wilson's August 2005 interview @ The New York Times

- Creel Commission Interview with Colin Wilson.

- Colin Wilson interviewed on poetry and the peak experience

- Colin Wilson interviewed by Lynn Barber 2004

- Colin Wilson: Philosopher of Optimism

|

KSF

KSF