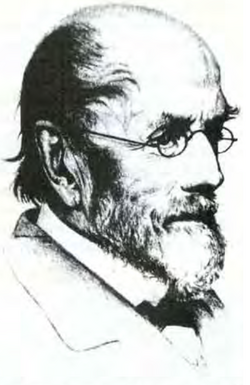

Hensleigh Wedgwood

Topic: Biography

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

Hensleigh Wedgwood | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 21 January 1803 Tarrant Gunville, Dorset, England |

| Died | 2 June 1891 (aged 88) Gower Street, London, England[1] |

| Resting place | Stoke Minster (The Church of St. Peter ad Vincula) [ ⚑ ] 53°00′15″N 02°10′53″W / 53.00417°N 2.18139°W |

| Alma mater | Christ's College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Barrister, magistrate, Philologist |

| Known for | Writing on English etymology |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 6 |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

Hensleigh Wedgwood (21 January 1803 – 2 June 1891) was a British etymologist, philologist and barrister, author of A Dictionary of English Etymology. He was a cousin of Charles Darwin, whom his sister Emma married in 1839.[1]

Early life

Wedgwood was born at Tarrant Gunville in Dorset, the fourth son of Josiah Wedgwood II and Elizabeth Allen of Cresselly, Pembrokeshire.[1]

He was educated at Rugby School, then entered St John's College, Cambridge in 1820 but switched to Christ's College the following year.[2] Although he did well in maths, graduating as 8th wrangler, he finished bottom in the classical tripos at Cambridge in 1824, for which he was awarded the first "wooden wedge", equivalent to the wooden spoon,[1] and jokingly named for him.[3]

Career

After leaving Cambridge, Wedgwood read for the chancery bar. In 1828, he qualified as a barrister, but never practised.[1] Between 1831 and 1837, he served as a police magistrate and sat at the Surrey magistrates' court at Union Hall, Southwark.[4]

A notable case that came before him during his tenure was that of James Pratt and John Smith in 1835, whom he committed to trial after their arrest for homosexual acts.[5] After their trial and conviction at the Central Criminal Court, the two became the last to be executed for sodomy in England. This was in spite of Wedgwood himself calling for a commutation of their death sentences in a letter to the Home Secretary.[6][7]

In 1837, Wedgwood resigned from the magistracy after deciding that one of his duties, the administrations of oaths, was inconsistent with the commandments of the New Testament.[8] Between 1838 and 1849, he held the post of Registrar of Metropolitan Public Carriage.[1]

His main fields of study were philology and etymology. His Dictionary of Etymology was published in 1857. He was a founding member of the Philological Society.[1]

Spiritualism

Wedgwood became interested in spiritualism and attended séances. In 1874, he attempted to get T.H. Huxley involved in spiritualism by sending him an alleged spirit photograph. Huxley was not impressed and suggested the photograph had been produced fraudulently by the use of a second image placed on the plate inside the camera. Hensleigh refused to believe this explanation and considered the photograph to be genuine.[9]

Wedgwood was a member of the British National Association of Spiritualists and a vice-president of the Society for Psychical Research.[10]

Personal life

He married, in 1832, Frances Emma Elizabeth "Fanny" Mackintosh (1800–1889), daughter of Catherine "Kitty" Allen (his maternal aunt) and James Mackintosh.[1] Their children include:

- Frances Julia Wedgwood (1833–1913), feminist, philosopher and writer.[11]

- James Mackintosh Wedgwood (1834–1864)[11]

- Miles Wedgwood (1835-1836)[12]

- Ernest Hensleigh Wedgwood (1837–1898)[11]

- Katherine Euphemia Wedgwood (1839–1934), married Thomas Farrer, 1st Baron Farrer.[11]

- Alfred Allen Wedgwood (1842–1892), father of J. I. Wedgwood.[11]

- Hope Elizabeth (1844–1935) married her cousin Godfrey Wedgwood.[11]

Wedgwood died on 2 June 1891 at his house at 94 Gower Street, London.[1] He was buried at the Church of St. Peter ad Vincula, Stoke on Trent, now known as Stoke Minster. His funeral on 4 June 1891 was noted in his sister's diary.[13]

His estate after death was valued at £123,694 (this would have been worth approximately £17 million in 2022) which was left to his wife Fanny and their five surviving children.[8]

Legacy

A collection of around 550 books from his library is held by the library of the University of Birmingham. They were donated to the university by his daughter, Frances Julia Wedgwood.[14]

Partial list of works

- The Principles of Geometrical Demonstration, 1844

- On the Development of Understanding, 1848.

- The Geometry of the Three First Books of Euclid by Direct Proofs from Definitions Alone, 1856.

- On the Origin of Language, 1866.

- A Dictionary of English Etymology, Second Edition, 1872.

- Contested Etymologies in the Dictionary of Rev. W. W. Skeat, 1882.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Herford, C.H.; Rev. John D. Haigh (2004). "Wedgwood, Hensleigh (1803–1891)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28965. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/28965. Retrieved 9 May 2010. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Wedgewood (or Wedgwood), Hensleigh (WGWT820H)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge. http://venn.lib.cam.ac.uk/cgi-bin/search-2018.pl?sur=&suro=w&fir=&firo=c&cit=&cito=c&c=all&z=all&tex=WGWT820H&sye=&eye=&col=all&maxcount=50.

- ↑ Bristed, Charles Astor (1852). Five years in an English university. G.P. Putnam. p. 253. https://archive.org/details/fiveyearsinanen00brisgoog.

- ↑ Bryant, Chris (2024). James and John. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 112-113. ISBN 978-1-5266-4497-8.

- ↑ Bryant, Chris (2024). James and John. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 116-117. ISBN 978-1-5266-4497-8.

- ↑ Cocks (2010) p. 38

- ↑ Upchurch (2009), p. 112.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bryant, Chris (2024). James and John. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 116-117. ISBN 978-1-5266-4497-8.

- ↑ Browne, E. Janet. (2003). Charles Darwin: The Power of Place, Volume 2. Princeton University Press. p. 404. ISBN 978-0691114392

- ↑ Oppenheim, Janet. (1988). The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850-1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0521347679

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Litchfield, Henrietta E. (1915). Emma Darwin, A century of family letters, 1792-1896. London: John Murray. p. xxvii.

- ↑ Marshall, Madison (2022). Reading kinship: intellectual influence, authorial formation, and the father-daughter relationship of Hensleigh and Julia 'Snow' Wedgwood. pp. 39, 319, https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/32691/.

- ↑ "Renshaw's Diary & Almanack 1891". http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=CUL-DAR242%5B.55%5D&viewtype=image&pageseq=1.

- ↑ "The Hensleigh Wedgwood collection". University of Birmingham. http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/facilities/cadbury/rarebooks/wedgwood.aspx.

Bibliography

- Cocks, H.G. (2010). Nameless Offences, Homosexual Desire in the 19th Century. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781848850903.

- Marshall, Madison (2022). Reading Kinship: Intellectual Influence, Authorial Formation and the Father-Daughter Relationship of Hensleigh and Julia 'Snow' Wedgwood. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/32691/

- Upchurch, Charles (2009). Before Wilde: Sex between Men in Britain's Age of Reform. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520258532.

External links

- Hensleigh Wedgwood profile, darwin.lib.cam.ac.uk

- Hensleigh Wedgwood and The Wooden Spoon @ Ward's Book of Days, wardsbookofdays.com

|

KSF

KSF