Isaac Hays

Topic: Biography

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

Isaac Hays | |

|---|---|

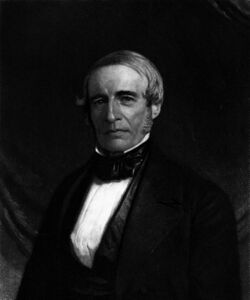

Isaac Hays c. 1850 | |

| Born | July 5, 1796 |

| Died | April 12, 1879 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Ophthalmologist, Editor |

| Signature | |

Isaac Hays (July 5, 1796 – April 12, 1879) was an American ophthalmologist, medical ethicist, and naturalist. A founding member of the American Medical Association, and the first president of the Philadelphia Ophthalmological Society, Hays published the first study of non-congential colorblindness and the first case of astigmatism in America. He was editor or co-editor of The American Journal of the Medical Sciences for over 50 years.

Early life and education

Isaac Hays was born on July 5, 1796, the second child and eldest son of Samuel and Richea (Gratz) Hays, and a nephew of educator and philanthropist Rebecca Gratz.[1] Hays's wealthy Philadelphia family was involved in the East India trade. After earning his bachelor's degree from the University of Pennsylvania in 1816, Hays briefly joined the family business, then opted to enter the Medical School of the University of Pennsylvania. Nathaniel Chapman mentored Hays during his training, beginning a decades-long friendship and professional collaboration.[2]

Ophthalmologist

Hays practiced ophthalmology for three and a half decades. Soon after graduating from the Medical School in 1820, Hays was appointed to the staff of McClellan's Institution for Diseases of the Eye and Ear. He later moved to the Pennsylvania Infirmary for Diseases of the Eye and Ear, and upon its opening in 1834 joined the staff of the Wills Hospital for the Relief of the Indigent Blind and Lame.[3] He remained at Wills until 1854, when he resigned due to "the pressure of literary work".[4]

During his stint at the Pennsylvania Infirmary, Hays wrote medical articles and contributed a chapter to William Potts Dewees's textbook Practice of Medicine (1833). At Wills, Hays published the first study of noncongenital color blindness, reported the first case of astigmatism in America, and devised a needle-knife for cataract surgery.[5]

Editor

Hubbell deemed Hays "fitted by Nature and by training for literary work"[6] and Hays's output would seem to confirm that judgment. More significant than his articles on medical and scientific topics, however, was his work as an editor.

He spent fifty-two years as editor or co-editor of The American Journal of the Medical Sciences.[7] He joined Nathaniel Chapman's staff in 1820 (then called the Philadelphia Journal of Medical and Physical Sciences), became the sole editor in 1841, and upon his retirement passed the editorial duties to his son, I. Minis Hays. Hays took particular care to include ophthalmology articles (the specialty did not have its own journal until 1862) and "Hays' journal" was very well regarded.[8]

Hays edited American editions of various books, including Sir William Lawrence's A Treatise on Diseases of the Eye (1843) and T. Wharton Jones's Principles and Practice of Ophthalmic Medicine and Surgery (1849), and supplemented the original material with his own.[9]

Natural scientist

Hays was among those Philadelphians who stubbornly advocated for an incremental theory of evolution, describing fossil vertebrates in the 1830s and '40s as supporting the theory of natural selection that eventually was elaborated by Charles Darwin in Origin of Species (1859).[10]

Hays argued that his name (Saurodon) for a New Jersey specimen should replace Richard Harlan's Saurocephalus on the grounds that Harlan's 1824 description of a specimen from Iowa was inaccurate.[11] Today, Saurodon and Saurocephalus are both genera belonging to the subfamily Saurodontinae.

In 1830, John D. Godman described a fossil specimen from Orange County, NY, as a new type of elephant, dubbing it Tetracaulodon. Harlan (whom Godman disliked and had accused of plagiarism) argued it was a juvenile mastodon. Hays took Godman's part, publishing a paper on the subject, Descriptions of the inferior maxillary bones of mastodons (1833). Across the Atlantic, Richard Owen initially joined Godman's camp and English transplant George Featherstonhaugh lectured in support of the juvenile mastodon theory that eventually prevailed worldwide.[12]

Hays was friends with Isaac Lea, who named the snail species Epioblasma haysiana (originally Unio haysianus)[13]: 35–36 and Elimia haysiana (originally Melania haysiana)[14] after Hays.

Organizations

Hays was among the founders of the American Medical Association, serving as its first treasurer and chairman of the Committee on Publications. He is also credited with the authorship of the AMA's first Code of Ethics.[15]

Hays was an honorary member of the American Ophthalmological Society (founded in 1864)[16] and the first president of the Philadelphia Ophthalmological Society (1870).[17] He took an active role in non-medical organizations, including the Academy of Natural Sciences, the Boston Academy of Arts and Sciences,[18] the American Philosophical Society,[19] and the Franklin Institute.[20]

Family

Hays married Sarah Ann Minis in Savannah on May 7, 1834. Sarah (affectionately called Sally) was the daughter of Isaac and Divinah (Cohen) Minis.[21] An old Savannah family, the Minises were among forty-one Jewish settlers who departed England in 1733[22] and Philip Minis (Sarah's paternal grandfather) had the distinction of being the first white child born in Georgia.[23]

Isaac and Sarah Hays had seven children: Joseph Gratz, William Dewees, Henrietta Minis, Theodore Minis, Frank, Isaac Minis, and Robert Griffin. All but Theodore and Robert survived to adulthood.[24] Isaac Minis Hays followed in his father's footsteps, training as an ophthalmologist, writing on medical subjects, joining learned societies, and editing The American Journal of the Medical Sciences.[25]

Isaac Hays died in 1879 during an influenza epidemic in Philadelphia. He left his first and only book, American Cyclopedia of Practical Medicine and Surgery, unfinished.[26]

Notes

- ↑ Stern, 87, 106.

- ↑ Morgenstern.

- ↑ Morgenstern.

- ↑ Hubbell, 44.

- ↑ Morgenstern.

- ↑ Hubbell, 43.

- ↑ "Medical journal celebrates 175th anniversary". http://www.emory.edu/EMORY_REPORT/erarchive/1995/January/ERjan.30/1.30.95med.journ.175.ann.html.

- ↑ Morgenstern.

- ↑ Morgenstern

- ↑ Thomson, 82-3.

- ↑ Thomson, 83.

- ↑ Thomson 83-4.

- ↑ Lea, Isaac (1834). "Observations on the naiades; and descriptions of new species of that, and other families". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 5: 23–119. doi:10.2307/1004939. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/35957690#page/57/mode/1up.

- ↑ Lea, Isaac (1842). "Continuation of Mr. Lea's paper on fresh water and land shells". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 9: 25. https://archive.org/stream/mobot31753003645519#page/25/mode/1up.

- ↑ Morgenstern.

- ↑ Morgenstern.

- ↑ Risley.

- ↑ Morgenstern.

- ↑ Carson, xi.

- ↑ Jones, 172.

- ↑ Stern, 194.

- ↑ Greenberg, 27, 31.

- ↑ Stern, 194.

- ↑ Stern, 106.

- ↑ Carson, xii-xiii.

- ↑ Morgenstern.

References

- Carson, Hampton L. "Address by Hampton L. Carson in Commemoration of I. Minis Hays." Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society Vol. LXV (1926): iii-xxxii.

- Greenberg, Mark I. "One Religion, Different Worlds: Sephardic and Ashkenazic Immigrants in Eighteenth-Century Savannah." In Jewish Roots in Southern Soil: A New History, edited by Marcie Cohen Ferris and Mark I. Greenberg, 27–45. Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England for Brandeis University Press, 2006.

- Hubbell, Alvin Allace. The Development of Ophthalmology in America, 1800 to 1870. Chicago: W. T. Keener & Company, 1908.

- Jones, Thomas P., editor. Journal of the Franklin Institute Vol. XXI. Philadelphia: Franklin Institute, 1838.

- Morgenstern, Leon. "Isaac Hays, MD: Nineteenth-Century Pioneer in Ophthalmology." Archives of Ophthalmology Vol. 122, No. 3 (2004): 385–387. Accessed July 6, 2011.

- Risley, Samuel D. "The Philadelphia Ophthalmological Society." Ophthalmic Literature Vol. VI, No. 1 (1916): 3–4.

- Stern, Malcolm Henry. First American Jewish Families: 600 Genealogies, 1654-1988. Ottenheimer Publishers, 1991. Online at The Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives. Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion: Cincinnati, OH. Accessed July 6, 2011.

- Thomson, Keith. Legacy of the Mastodon: The Golden Age of Fossils in America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008.

KSF

KSF