Johann Christian Poggendorff

Topic: Biography

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

Johann Christian Poggendorff | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | |

| Died | 24 January 1877 (aged 80) |

| Known for | Poggendorff cell Poggendorff illusion Mirror galvanometer Potentiometer |

Johann Christian Poggendorff (29 December 1796 – 24 January 1877), was a German physicist born in Hamburg. By far the greater and more important part of his work related to electricity and magnetism. Poggendorff is known for his electrostatic motor which is analogous to Wilhelm Holtz's electrostatic machine. In 1841 he described the use of the potentiometer for measurement of electrical potentials without current draw.[1]

Biography

Poggendorf had apprenticed himself to an apothecary in Hamburg, and when twenty-two began to earn his living as an apothecary's assistant at Itzehoe. Ambition and a strong inclination towards a scientific career led him to throw up his business and move to Berlin, where he entered Humboldt University in 1820. Here his abilities were speedily recognized, and in 1823 he was appointed meteorological observer to the Academy of Sciences.

Even at this early period he had conceived the idea of founding a physical and chemical scientific journal, and the realization of this plan was hastened by the sudden death of Ludwig Wilhelm Gilbert, the editor of Gilbert's Annalen der Physik, in 1824 Poggendorff immediately put himself in communication with the publisher, Barth of Leipzig. He became editor of Annalen der Physik und Chemie, which was to be a continuation of Gilbert's Annalen on a somewhat extended plan. Poggendorff was admirably qualified for the post, and edited the journal for 52 years, until 1876. In 1826, Poggendorff developed the mirror galvanometer, a device for detecting electric currents.

He had an extraordinary memory, well stored with scientific knowledge, both modern and historical, a cool and impartial judgment, and a strong preference for facts as against theory of the speculative kind. He was thus able to throw himself into the spirit of modern experimental science. He possessed in abundant measure the German virtue of orderliness in the arrangement of knowledge and in the conduct of business. Further he had an engaging geniality of manner and much tact in dealing with men. These qualities soon made Poggendorff's Annalen (abbreviation: Pogg. Ann.) the foremost scientific journal in Europe.

In the course of his fifty-two years editorship of the Annalen Poggendorff could not fail to acquire an unusual acquaintance with the labors of modern men of science. This knowledge, joined to what he had gathered by historical reading of equally unusual extent, he carefully digested and gave to the world in his Biographisch-literarisches Handworterbuch zur Geschichte der exacten Wissenschaften, containing notices of the lives and labors of mathematicians, astronomers, physicists, and chemists, of all peoples and all ages. This work contains an astounding collection of facts invaluable to the scientific biographer and historian. The first two volumes were published in 1863; after his death a third volume appeared in 1898, covering the period 1858-1883, and a fourth in 1904, coming down to the beginning of the 20th century.

His literary and scientific reputation speedily brought him honorable recognition. In 1830 he was made royal professor, in 1838 Hon. Ph.D. and extraordinary professor in the University of Berlin, and in 1839 member of the Berlin Academy of Sciences. In 1845, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Many offers of ordinary professorships were made to him, but he declined them all, devoting himself to his duties as editor of the Annalen, and to the pursuit of his scientific researches. He died at Berlin on 24 January 1877.[2]

His daughter Marie Poggendorff (born 12 August 1838) married Valentin Rose in 1872.

Illusion

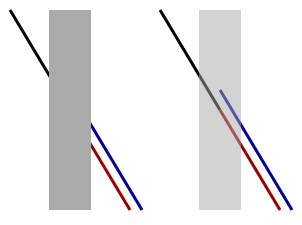

The Poggendorff Illusion is an optical illusion that involves the brain's perception of the interaction between diagonal lines and horizontal and vertical edges. It is named after Poggendorff, who discovered it in the drawing of Johann Karl Friedrich Zöllner, in which he showed the Zöllner illusion in 1860.[3] In the adjacent picture, a straight black line is obscured by a dark gray rectangle. The black line appears disjointed, although it is in fact straight; the second picture illustrates this fact.

See also

- Chromic acid cell

Publications

- (in de) Biographisch-literarisches Handwörterbuch zur Geschichte der exakten Wissenschaften. 1. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth. 1863. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=7175387.

- (in de) Biographisch-literarisches Handwörterbuch zur Geschichte der exakten Wissenschaften. 2. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth. 1863. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=7177826.

- (in de) Biographisch-literarisches Handwörterbuch zur Geschichte der exakten Wissenschaften. 3. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth. 1898. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=7180073.

- (in de) Biographisch-literarisches Handwörterbuch zur Geschichte der exakten Wissenschaften. 4. Leipzig: Johann Ambrosius Barth. 1904. https://gutenberg.beic.it/webclient/DeliveryManager?pid=6729669.

- J. C. Poggendorff, Annalen Der Physik, Ser. 2, Vol. 139, pp 513–546 (1870)

- J. C. Poggendorff, "Biographisch-Literarisches Handwörterbuch der exakten Naturwissenschaften" "(Tr. "biographic-literary hand dictionary of the exact sciences"). Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig, 1863. Two volumes, Band 2 (M-Z) at Google Books (weitergeführt in den Bänden III bis VIII durch die Sächsische Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Leipzig)

- Biographisch-Literarisches Handwörterbuch[4]

- Emil Frommel, Johann Christian Poggendorff (Berlin, 1877)

- Lebenslinien zur Geschichte der exacten Wissenschaften seit Wiederherstellung derselben. Alexander Duncker, Berlin 1853. Johann Christian Poggendorff at Google Books

- Geschichte der Physik. Joh. Ambr. Barth, Leipzig 1879. US at Google Books, US at Google Books, at the Internet Archive

References

- ↑ http://physics.kenyon.edu/EarlyApparatus/Electrical_Measurements/Potentiometer/Potentiometer.html Potentiometer, retrieved 2010 Nov 2

- ↑ American Academy of Arts and Sciences Daedalus: proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Volume 12, 1877 page 330-331

- ↑ Zöllner F (1860). "Ueber eine neue Art von Pseudoskopie und ihre Beziehungen zu den von Plateau und Oppel beschriebenen Bewegungsphänomenen". Annalen der Physik 186 (7): 500–25. doi:10.1002/andp.18601860712. Bibcode: 1860AnP...186..500Z. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k151955/f512.table.

- ↑ Website of Poggendorff's Biographisch-Literarisches Handwörterbuch

Sources

External links

- General

- Johann Christian Poggendorff at Open Library

- Poggendorff's disk, f3wm.free.fr, 2004-11-08.

- Illusion

- Poggendorf Illusion

- Circular Poggendorf Illusion

- Poggendorf Illusion

- Explanation of the Poggendorff, Hering, and Zoellner illusions

|

KSF

KSF