Paulo Freire

Topic: Biography

From HandWiki - Reading time: 20 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 20 min

Paulo Freire | |

|---|---|

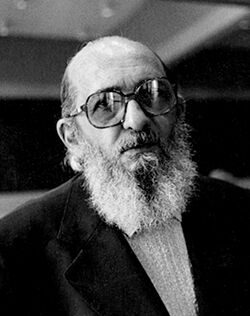

Freire in 1977 | |

| Born | Paulo Reglus Neves Freire 19 September 1921 Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil |

| Died | 2 May 1997 (aged 75) São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil |

| Education | Universidade Federal de Pernambuco |

| Political party | Workers' Party |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Scholarly background | |

| Influences |

|

| Scholarly work | |

| Discipline | |

| School or tradition | |

| Doctoral students | Mario Sergio Cortella |

| Notable works | Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) |

| Notable ideas |

|

| Influenced |

|

| Signature | |

Paulo Reglus Neves Freire[lower-alpha 1] (19 September 1921 – 2 May 1997) was a Brazilian educator and philosopher who was a leading advocate of critical pedagogy. His influential work Pedagogy of the Oppressed is generally considered one of the foundational texts of the critical pedagogy movement,[23][24][25] and was the third most cited book in the social sciences as of 2016[update] according to Google Scholar.[26]

Biography

Freire was born on 19 September 1921 to a middle-class family in Recife, the capital of the northeastern Brazilian state of Pernambuco. He became familiar with poverty and hunger from an early age as a result of the Great Depression. In 1931 his family moved to the more affordable city of Jaboatão dos Guararapes, 18 km west of Recife. His father died on 31 October 1934.[27]

During his childhood and adolescence, Freire ended up four grades behind, and his social life revolved around playing pick-up football with other poor children, from whom he claims to have learned a great deal. These experiences would shape his concerns for the poor and would help to construct his particular educational viewpoint. Freire stated that poverty and hunger severely affected his ability to learn. These experiences influenced his decision to dedicate his life to improving the lives of the poor: "I didn't understand anything because of my hunger. I wasn't dumb. It wasn't lack of interest. My social condition didn't allow me to have an education. Experience showed me once again the relationship between social class and knowledge".[28] Eventually, his family's misfortunes turned around and their prospects improved.[28]

Freire enrolled in law school at the University of Recife in 1943. He also studied philosophy, more specifically phenomenology, and the psychology of language. Although admitted to the legal bar, he never practiced law and instead worked as a secondary school Portuguese teacher. In 1944, he married Elza Maia Costa de Oliveira, a fellow teacher. The two worked together and had five children.[29]

In 1946, Freire was appointed director of the Pernambuco Department of Education and Culture. Working primarily among the illiterate poor, Freire began to develop an educational praxis that would have an influence on the liberation theology movement of the 1970s. In 1940s Brazil, literacy was a requirement for voting in presidential elections.[30][31]

File:Paulo Freire (1963).tif In 1961, he was appointed director of the Department of Cultural Extension at the University of Recife. In 1962, he had the first opportunity for large-scale application of his theories, when, in an experiment, 300 sugarcane harvesters were taught to read and write in just 45 days. In response to this experiment, the Brazilian government approved the creation of thousands of cultural circles across the country.[32]

The 1964 Brazilian coup d'état put an end to Freire's literacy effort, as the ruling military junta did not endorse it. Freire was subsequently imprisoned as a traitor for 70 days. After a brief exile in Bolivia, Freire worked in Chile for five years for the Christian Democratic Agrarian Reform Movement and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. In 1967, Freire published his first book, Education as the Practice of Freedom. He followed it up with his most famous work, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which was first published in 1968.

After a positive international reception of his work, Freire was offered a visiting professorship at Harvard University in 1969. The next year, Pedagogy of the Oppressed was published in Spanish and English, vastly expanding its reach. Because of political feuds between Freire, a Christian socialist, and Brazil's successive right-wing authoritarian military governments, the book went unpublished in Brazil until 1974, when, starting with the presidency of Ernesto Geisel, the military junta started a process of slow and controlled political liberalisation.[citation needed]

Following a year in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Freire moved to Geneva to work as a special education advisor to the World Council of Churches. During this time Freire acted as an advisor on education reform in several former Portuguese colonies in Africa, particularly Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique.

In 1979, he first visited Brazil after more than a decade of exile, eventually moving back in 1980. Freire joined the Workers' Party (PT) in São Paulo and acted as a supervisor for its adult literacy project from 1980 to 1986. When the Workers' Party won the 1988 São Paulo mayoral elections in 1988, Freire was appointed municipal Secretary of Education.

Freire is widely considered the grandfather of Critical Education Theory.

Freire died of heart failure on 2 May 1997, in São Paulo.[33]

Pedagogy

There is no such thing as a neutral education process. Education either functions as an instrument which is used to facilitate the integration of generations into the logic of the present system and bring about conformity to it, or it becomes the "practice of freedom", the means by which men and women deal critically with reality and discover how to participate in the transformation of their world.

— Jane Thompson, drawing on Paulo Freire[34]

Freire contributed a philosophy of education which blended classical approaches stemming from Plato and modern Marxist, post-Marxist, and anti-colonialist thinkers. His Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1968) can be read as an extension of, or reply to, Frantz Fanon's The Wretched of the Earth (1961), which emphasized the need to provide native populations with an education which was simultaneously new and modern, rather than traditional, and anti-colonial – not simply an extension of the colonizing culture.

In Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Freire, reprising the oppressors–oppressed distinction, applies the distinction to education, championing that education should allow the oppressed to regain their sense of humanity, in turn overcoming their condition. Nevertheless, he acknowledges that for this to occur, the oppressed individual must play a role in their liberation.

No pedagogy which is truly liberating can remain distant from the oppressed by treating them as unfortunates and by presenting for their emulation models from among the oppressors. The oppressed must be their own example in the struggle for their redemption.[35]

Likewise, oppressors must be willing to rethink their way of life and to examine their own role in oppression if true liberation is to occur: "Those who authentically commit themselves to the people must re-examine themselves constantly".[36]

Freire believed education could not be divorced from politics; the act of teaching and learning are considered political acts in and of themselves. Freire defined this connection as a main tenet of critical pedagogy. Teachers and students must be made aware of the politics that surround education. The way students are taught and what they are taught serves a political agenda. Teachers, themselves, have political notions they bring into the classroom.[37] Freire believed that

Education makes sense because women and men learn that through learning they can make and remake themselves, because women and men are able to take responsibility for themselves as beings capable of knowing—of knowing that they know and knowing that they don't.[38]

Criticism of the "banking model" of education

In terms of pedagogy, Freire is best known for his attack on what he called the "banking" concept of education, in which students are viewed as empty accounts to be filled by teachers. He notes that "it transforms students into receiving objects [and] attempts to control thinking and action, lead[ing] men and women to adjust to the world, inhibit[ing] their creative power."[39] The basic critique was not entirely novel, and paralleled Jean-Jacques Rousseau's conception of children as active learners, as opposed to a tabula rasa view, more akin to the banking model.[40] John Dewey was also strongly critical of the transmission of mere facts as the goal of education. Dewey often described education as a mechanism for social change, stating that "education is a regulation of the process of coming to share in the social consciousness; and that the adjustment of individual activity on the basis of this social consciousness is the only sure method of social reconstruction".[41] Freire's work revived this view and placed it in context with contemporary theories and practices of education, laying the foundation for what would later be termed critical pedagogy.

Culture of silence

According to Freire, unequal social relations create a "culture of silence" that instills the oppressed with a negative, passive and suppressed self-image; learners must, then, develop a critical consciousness in order to recognize that this culture of silence is created to oppress.[42] A culture of silence can also cause the "dominated individuals [to] lose the means by which to critically respond to the culture that is forced on them by a dominant culture."[43]

He considers social, race and class dynamics to be interlaced into the conventional education system, through which this culture of silence eliminates the "paths of thought that lead to a language of critique."[44]

Legacy and reception

Since the publication of the English-language edition in 1970, Pedagogy of the Oppressed has had a large impact in education and pedagogy worldwide,({{{1}}}, {{{2}}}) especially as a defining work of critical pedagogy. According to Israeli writer and education reform theorist Sol Stern, it has "achieved near-iconic status in America's teacher-training programs".[45] Connections have also been made between Freire's non-dualism theory in pedagogy and Eastern philosophical traditions such as the Advaita Vedanta.[46]

In 1977, the Adult Learning Project, based on Freire's work, was established in the Gorgie-Dalry neighborhood of Edinburgh, Scotland.[47] This project had the participation of approximately 200 people in the first years, and had among its aims to provide affordable and relevant local learning opportunities and to build a network of local tutors.[47] In Scotland, Freire's ideas of popular education influenced activist movements[48] not only in Edinburgh but also in Glasgow.[49]

Freire's major exponents in North America are bell hooks,[50] Henry Giroux, Peter McLaren, Donaldo Macedo, Antonia Darder, Joe L. Kincheloe, Shirley R. Steinberg, Carlos Alberto Torres, and Ira Shor.[51] One of McLaren's edited texts, Paulo Freire: A Critical Encounter, expounds upon Freire's impact in the field of critical pedagogy. McLaren has also provided a comparative study concerning Paulo Freire and Argentinian revolutionary icon Che Guevara. Freire's work influenced the radical math movement in the United States, which emphasizes social justice issues and critical pedagogy as components of mathematical curricula.[52]

In South Africa, Freire's ideas and methods were central to the 1970s Black Consciousness Movement, often associated with Steve Biko,[53][54] as well as the trade union movement in the 1970s and 1980s, and the United Democratic Front in the 1980s.[55] The radical doctor Abu Baker Asvat was among the many prominent anti-apartheid activists who used Freire's methods.[56] Today there is a Paulo Freire Project at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in Pietermaritzburg[57] and Abahlali baseMjondolo, a radical movement of the urban poor, continues to use Freirian methods.[58]

In 1991, the Paulo Freire Institute was established in São Paulo to extend and elaborate upon his theories of popular education. The institute has started projects in many countries and is headquartered at the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies, where it actively maintains the Freire archives. Its director is UCLA professor Carlos Torres, the author of several Freirean works, including the 1978 A praxis educativa de Paulo Freire.[59][60]

In 1999 PAULO, a national training organisation named in honour of Freire, was established in the United Kingdom. This agency was approved by the New Labour Government to represent some 300,000 community-based education practitioners working across the UK. PAULO was given formal responsibility for setting the occupational training standards for people working in this field.[61]

The Paulo and Nita Freire Project for International Critical Pedagogy was founded at McGill University. Here Joe L. Kincheloe and Shirley R. Steinberg worked to create a dialogical forum for critical scholars around the world to promote research and re-create a Freirean pedagogy in a multinational domain.[62] After the death of Kincheloe, the project was transformed into a virtual global resource.[63]

In 2012, a group of educators in Western Massachusetts, United States, received permission to name a public school after Freire. The Holyoke, Massachusetts, Paulo Freire Social Justice Charter School opened in September 2013.[64] The school moved to the former Pope Francis Catholic High School building in Chicopee, Massachusetts, in 2019.[65]

In 2012, Paolo Freire Charter High School opened in Newark, New Jersey. The state closed the school in 2017 due to lagging test scores and lack of "instructional rigor."[66]

Shortly before his death, Freire was working on a book of ecopedagogy, a platform of work carried on by many of the Freire Institutes and Freirean Associations around the world today. It has been influential in helping to develop planetary education projects such as the Earth Charter as well as countless international grassroots campaigns in the spirit of Freirean popular education generally.[67]

Freirean literacy methods have been adopted throughout the developing world. In the Philippines, Catholic "basal Christian communities" adopted Freire's methods in community education. Papua New Guinea, Freirean literacy methods were used as part of the World Bank-funded Southern Highlands Rural Development Program's Literacy Campaign. Freirean approaches also lie at the heart of the "Dragon Dreaming" approach to community programs that have spread to 20 countries by 2014.[68]

Awards and honors

- King Baudouin International Development Prize 1980: Paulo Freire was the first person to receive this prize. He was nominated by Mathew Zachariah, Professor of Education at the University of Calgary.

- Prize for Outstanding Christian Educators, with his wife Elza

- UNESCO Prize for Peace Education 1986

- Honorary Doctorate, the University of Nebraska at Omaha, 1996, along with Augusto Boal, during their residency at the Second Pedagogy and Theatre of the Oppressed Conference in Omaha.

- Honorary Degree from Claremont Graduate University, 1992

- Honorary Doctorate from The Open University, 1973

- Inducted, International Adult and Continuing Education Hall of Fame, 2008[69]

- Honorary Degree from the University of Illinois at Chicago, 1993.[70]

Bibliography

Freire wrote and co-wrote over 20 books on education, pedagogy and related themes.[71]

Some of his works include:

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, Continuum.

- Freire, P. (1970). Cultural Action for Freedom. [Cambridge], Harvard Educational Review.

- Freire, P. (1973). Education for Critical Consciousness. New York, Seabury Press.

- Freire, P. (1975). Conscientization. Geneva, World Council of Churches.

- Freire, P. (1976). Education, the Practice of Freedom. London, Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative.

- Freire, P. (1978). Pedagogy in Process: The Letters to Guinea-Bissau. New York, A Continuum Book: The Seabury Press.

- Freire, P. (1985). The Politics of Education: Culture, Power, and Liberation. South Hadley, Massachusetts , Bergin & Garvey.

- Freire, P. & D.P. Macedo (1987). Literacy: Reading the Word & the World. South Hadley, MA, Bergin & Garvey Publishers.

- Freire, P. & I. Shor (1987). Freire for the Classroom: A Sourcebook for Liberators Teaching.

- Freire, P. and H. Giroux & P. McLaren (1988). Teachers as Intellectuals: Towards a Critical Pedagogy of Learning.

- Freire, P. & I. Shor (1988). Cultural Wars: School and Society in the Conservative Restoration, 1969–1984.

- Freire, P. (1993). Pedagogy of the City. New York, Continuum.

- Faundez, Antonion, and Paulo Freire (1992). Learning to Question: A Pedagogy of Liberation. Trans. Tony Coates, New York, Continuum.

- Freire, P. and A.M.A. Freire (1994). Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York, Continuum.

- Freire, P. (1997). Mentoring the Mentor: A Critical Dialogue with Paulo Freire. New York, P. Lang.

- Freire, P. & A.M.A. Freire (1997). Pedagogy of the Heart. New York, Continuum.

- Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy and Civic Courage. Lanham, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Freire, P. (1998). Politics and Education. Los Angeles, UCLA Latin American Center Publications.

- Freire, P. (1998). Teachers as Cultural Workers: Letters to Those Who Dare Teach. Boulder, CO, Westview Press.

See also

- Adult education

- Michael Apple

- John Asimakopoulos

- Clodomir Santos de Morais

- Culture circle

- Dialogic education

- Dialogic learning

- Dialogic pedagogy

- Raya Dunayevskaya

- Education in Brazil

- Lewis Gordon

- James D. Kirylo

- Landless Workers' Movement

- Marxist humanism

- Paulo Freire University

- Peer mentoring

- Popular education

- Praxis intervention

- Problem-posing education

- Rouge Forum

- Second Episcopal Conference of Latin America

- Structure and agency

Notes

- ↑ English pronunciation: /ˈfrɛəri/ FRAIR-ee; Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈpawlu ˈfɾejɾi] (

listen).[citation needed]

listen).[citation needed]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Stone 2013, p. 45.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kirkendall 2010, p. 21.

- ↑ Kahn & Kellner 2008, p. 30.

- ↑ Rocha 2018, pp. 371–372.

- ↑ https://iftm.edu.br/simpos/2018/anais/758-%20Pronto%20ANAIS.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 Díaz n.d.

- ↑ Rocha 2018, pp. 371–372, 379.

- ↑ Fateh 2020, p. 2.

- ↑ "Review Board | Visual Culture & Gender". http://vcg.emitto.net/index.php/vcg/reviewBoard.

- ↑ Ballengee Morris 2008, pp. 55, 60, 65.

- ↑ Ballengee Morris 2008, p. 55.

- ↑ Kirylo 2011, pp. 244–245.

- ↑ Luschei & Soto-Peña 2019, p. 122.

- ↑ Flecha 2013, p. 21.

- ↑ Kohan 2018, p. 619.

- ↑ Prodnik & Hamelink 2017, p. 271.

- ↑ "Karen Keifer-Boyd, Ph.D.". http://www.personal.psu.edu/faculty/k/t/ktk2/syllabi/3362/khome.html.

- ↑ Kirylo 2011, p. xxii.

- ↑ https://thelearningexchange.ca/projects/allan-luke-the-new-literacies/ approx. 1:47

- ↑ https://cabodostrabalhos.ces.uc.pt/n14/documentos/06_MoaraCrivelente.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ↑ Kirylo 2011, p. 258.

- ↑ "Our Programs | Georgia Conflict Center". https://www.gaconflict.org/our-programs?32d2740e_page=2.

- ↑ Wyllie, Justin (7 June 2012). "Review of Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed". https://thenewobserver.co.uk/2012/06/07/review-of-paulo-freires-pedagogy-of-the-oppressed-2/.

- ↑ Barmania, Sima (26 October 2011). "Why Paulo Freire's 'Pedagogy of the Oppressed' Is Just as Relevant Today as Ever". London. http://blogs.independent.co.uk/2011/10/26/why-paulo-freires-pedagogy-of-the-oppressed-is-just-as-relevant-today-as-ever/.

- ↑ "Paulo Freire". infed. 2002. http://www.infed.org/thinkers/et-freir.htm.

- ↑ Elliott D. Green (2016-05-12). "What are the most-cited publications in the social sciences (according to Google Scholar)?". London School of Economics and Political Science. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/66752.

- ↑ Freire 1996.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Stevens, Christy. "Paulo Freire". Iowa City, IO: University of Iowa. http://mingo.info-science.uiowa.edu/~stevens/critped/freire.htm.

- ↑ Ramalho, Tania (2018-11-20) (in en), Paulo Freire and Communication Studies, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.608, ISBN 978-0-19-022861-3, https://oxfordre.com/communication/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228613-e-608, retrieved 2024-01-13

- ↑ Bethell 2000.

- ↑ "The Great Leap Forward: The Political Economy of Education in Brazil, 1889–1930". HBS Working Knowledge. 29 April 2010. https://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/the-great-leap-forward-the-political-economy-of-education-in-brazil-1889-1930.

- ↑ Oxman, Richard (26 April 2017). "Securing Sweetness For Sugarcane Souls: A Tribute To Paulo Freire" (in en-US). Countercurrents. https://countercurrents.org/2017/04/securing-sweetness-for-sugarcane-souls-a-tribute-to-paulo-freire/.

- ↑ Pace, Eric (6 May 1997). "Paulo Freire, 75, Is Dead; Educator of the Poor in Brazil". The New York Times: p. D23. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1997/05/06/world/paulo-freire-75-is-dead-educator-of-the-poor-in-brazil.html.

- ↑ Mayo 1999, p. 5.

- ↑ Freire 1971, p. 39.

- ↑ Freire 1971, p. 47.

- ↑ Kincheloe 2008.

- ↑ Freire 2016, p. 15.

- ↑ Freire 1971, p. 64.

- ↑ Bogle, Steven (2021). "A critique of A Curriculum for Excellence through the works of Paulo Freire". https://theses.gla.ac.uk/82405/13/2021BogleMPhil%28R%29.pdf.

- ↑ Dewey 1897, p. 16.

- ↑ "Marxist education:Education by Freire". Tx.cpusa.org. http://tx.cpusa.org/school/classics/freire.htm.

- ↑ "Paulo Freire". Education.miami.edu. http://www.education.miami.edu/ep/contemporaryed/Paulo_Freire/paulo_freire.html.

- ↑ Giroux, Henry A. (2001). "Culture, Power and Transformation in the Work of Paulo Freire". in Schultz, Fred. Sources: Notable Selections in Education Selections in Education (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Dushkin. p. 80. Cited in Cortez, John. "Culture, Power and Transformation in the Work of Paulo Freire, by Henry A. Giroux". New York: Fordham University. p. 5. http://faculty.fordham.edu/kpking/classes/uege5102-pres-and-newmedia/Giroux-John-Cortez-Presentation.pdf.

- ↑ Stern, Sol (Spring 2009). "Pedagogy of the Oppressor". City Journal (New York: Manhattan Institute for Policy Research). https://www.city-journal.org/html/pedagogy-oppressor-13168.html. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ↑ Sriraman 2008.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Kirkwood & Kirkwood 2011.

- ↑ Kane 2010.

- ↑ "Paulo Freire". 24 May 1997. https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/12326184.paulo-freire/.

- ↑ hooks, bell (1994). Teaching to transgress : education as the practice of freedom. New York. ISBN 0-415-90807-8. OCLC 30668295. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/30668295.

- ↑ "Paulo Freire | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy" (in en-US). https://iep.utm.edu/freire/.

- ↑ "Radical Math". http://www.radicalmath.org/.

- ↑ Timmel, Sally (29 December 2015). "Anne Hope – A Woman of Substance in Anti-Apartheid Movement". Cape Times. Cape Town. https://www.iol.co.za/capetimes/opinion/anne-hope-a-woman-of-substance-in-anti-apartheid-movement-1964986.

- ↑ Liberation and Development: Black Consciousness Community Programs in South Africa, Leslie Anne Hadfield,2016

- ↑ Pithouse, Richard (4 August 2017). "Art of Listening Is at Heart of True Democracy". Mail & Guardian (Johannesburg). https://mg.co.za/article/2017-08-04-00-art-of-listening-is-at-heart-of-true-democracy.

- ↑ Abu Baker Asvat: a forgotten revolutionary, Imraan Buccus, New Frame, 8 November 2021

- ↑ "Paulo Freire Project". http://cae.ukzn.ac.za/PauloFreireProject.aspx.

- ↑ Paulo Freire and Popular Struggle in South Africa, Zamalotshwa Sefatsa, Tricontinental Institute for Social Research, 9 November 2020

- ↑ "About | School of Education & Information Studies" (in en). https://www.pfi.seis.ucla.edu/about.

- ↑ Torres, Carlos Alberto (1977). "A práxis educativa de Paulo Freire" (in pt). Produção de terceiros sobre Paulo Freire; Série Livros. https://acervo.paulofreire.org/handle/7891/1628.

- ↑ "Latest version of the UK's National Occupational Standards for Community Development out – IACD" (in en-US). https://www.iacdglobal.org/2015/10/31/latest-version-of-the-uks-national-occupational-standards-for-community-development-out/.

- ↑ "The Paulo and Nita Freire Project for Critical Pedagogy, McGill University | Centre for Culture, Identity and Education". https://ccie.educ.ubc.ca/the-paulo-and-nita-freire-project-for-critical-pedagogy-mcgill-university/.

- ↑ "The Freire Project" (in en). https://freireproject.com/.

- ↑ Vaznis, James (28 February 2012). "State Approves Four New Charter Schools". The Boston Globe. https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2012/02/28/state-approves-four-new-charter-schools/vJSYRGhkz9rgEBqwaPMyGI/story.html.

- ↑ Christensen, Dusty (June 24, 2021). "Dozens protest as Paulo Freire charter school axes half its teachers". Daily Hampshire Gazette. https://www.gazettenet.com/Paulo-Freire-Social-Justice-Charter-School-union-alleges-union-busting-41135304.

- ↑ Clark, Adam (2017-03-02). "Here are the specific reasons N.J. closed these 4 charter schools" (in en). https://www.nj.com/education/2017/03/heres_why_nj_closed_these_4_charter_schools.html.

- ↑ Earth Charter Initiative Secretariat. "The Earth Charter and Education for Social Change". https://earthcharter.org/wp-content/assets/virtual-library2/images/uploads/X-%20The%20Earth%20Charter%20and%20Education%20for%20Social%20Change.pdf.

- ↑ Disterheft, Antje (2015). "PARTICIPATORY APPROACHES IN HIGHER EDUCATION'S SUSTAINABILITY PRACTICES: A MIXED-METHODS STUDY LEADING TO A PROPOSAL OF A NEW ASSESSMENT MODEL". https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/303043452.pdf.

- ↑ "International Adult Continuing Education Hall of Fame". http://www.halloffame.outreach.ou.edu/by_year/HOF_2008.html.

- ↑ "Honorary Degrees | Commencement | University of Illinois at Chicago". https://commencement.uic.edu/about/history/honorary-degrees/.

- ↑ "Bibliography". Pedagogy of the oppressed. http://www.pedagogyoftheoppressed.com/bibliography/.

Works cited

- Aitken, Mel; Shaw, Mae, eds (2018). "Pedagogy of the Oppressed". Concept 9 (3). ISSN 2042-6968. http://concept.lib.ed.ac.uk/article/view/2849/3906.

- Arney, Lance A. (2007). Political Pedagogy and Art Education with Youth in a Street Situation in Salvador, Brazil: An Ethnographic Evaluation of the Street Education Program of Projeto Axé (MA thesis). Tampa, Florida: University of South Florida. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Ballengee Morris, Christine (2008). "Paulo Freire: Community-Based Arts Education". Journal of Thought 43 (1–2): 55–69. ISSN 2375-270X.

- Bethell, Leslie (2000). "Politics in Brazil: From Elections Without Democracy to Democracy Without Citizenship". Daedalus 129 (2): 1–27. ISSN 1548-6192.

- Blunden, Andy (2013). "Contradiction, Consciousness, and Generativity: Hegel's Roots in Freire's Work". in Lake, Robert; Kress, Tricia. Paulo Freire's Intellectual Roots: Toward Historicity in Praxis. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 11–28. doi:10.5040/9781472553164.ch-001. ISBN 978-1-4411-1380-1. http://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/1002832/1fb090e71ce54337371cb171375ebda9.pdf. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- Clare, Roberta (n.d.). "Paulo Freire". Christian Educators of the 20th Century. La Mirada, California: Biola University. https://www.biola.edu/talbot/ce20/database/paulo-freire. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- Cruz, Ana L. (2013). "Paulo and Nita: Sharing Life, Love and Intellect – An Introduction". International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 5 (1): 5–10. ISSN 2157-1074. http://libjournal.uncg.edu/ijcp/article/view/770. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- Dewey, John (1897). My Pedagogic Creed. New York: E. L. Kellogg & Co.. https://archive.org/details/mypedagogiccree00dewegoog. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- Díaz, Kim (n.d.). "Paulo Freire (1921–1997)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://iep.utm.edu/freire/. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- Fateh, Mohammad (2020). A Historical Analysis on Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) and Abed's Reception of Paulo Freire's Critical Literacy in Designing BRAC's Functional Education Curriculum in Bangladesh from 1972 to 1981 (MEd thesis). Kingston, Ontario: Queen's University. hdl:1974/27558.

- Flecha, Ramón (2013). "Life Experiences with Paulo and Nita". International Journal of Critical Pedagogy 5 (1): 17–24. ISSN 2157-1074. http://libjournal.uncg.edu/ijcp/article/view/772. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- Freire, Paulo (1971). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Herder and Herder. OCLC 1036794065.

- ——— (1985). The Politics of Education: Culture, Power, and Liberation. Critical Studies in Education. Westport, Connecticut: Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 978-0-89789-043-4.

- ——— (1996). Letters to Cristina: Reflections on My Life and Work. New York: Routledge.

- ——— (2016). Pedagogy of Indignation. Abingdon, England: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315632902. ISBN 978-1-59451-050-2.

- Grollios, Georgios (2016). Paulo Freire and the Curriculum. Abingdon, England: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315632988. ISBN 978-1-59451-747-1.

- Kahn, Richard; Kellner, Douglas (2008). "Paulo Freire and Ivan Illich: Technology, Politics, and the Reconstruction of Education". in Torres, Carlos Alberto; Noguera, Pedro. Social Justice Education for Teachers: Paulo Freire and the Possible Dream. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers. pp. 13–34. doi:10.1163/9789460911446_003. ISBN 978-94-6091-144-6.

- Kane, Liam (2010). "Community Development: Learning from Popular Education in Latin America". Community Development Journal 45 (3): 276–286. doi:10.1093/cdj/bsq021. ISSN 1468-2656.

- Kirkendall, Andrew J. (2010). Paulo Freire and the Cold War Politics of Literacy. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-3419-0.

- Kirkwood, Gerri; Kirkwood, Colin (2011). Living Adult Education: Freire in Scotland (2nd ed.). Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers. ISBN 978-94-6091-552-9.

- Kirylo, James D. (2011). Paulo Freire: The Man from Recife. Counterpoints: Studies in the Postmodern Theory of Education. 385. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0879-2.

- Kohan, Walter Omar (2018). "Paulo Freire and Philosophy for Children: A Critical Dialogue". Studies in Philosophy and Education 37 (6): 615–629. doi:10.1007/s11217-018-9613-8. ISSN 1573-191X.

- Kress, Tricia; Lake, Robert (2013). "Freire and Marx in Dialogue". in Lake, Robert; Kress, Tricia. Paulo Freire's Intellectual Roots: Toward Historicity in Praxis. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 29–52. doi:10.5040/9781472553164.ch-002. ISBN 978-1-4411-1380-1. http://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/1002832/1fb090e71ce54337371cb171375ebda9.pdf. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- Lake, Robert; Dagostino, Vicki (2013). "Converging Self/Other Awareness: Erich Fromm and Paulo Freire on Transcending the Fear of Freedom". in Lake, Robert; Kress, Tricia. Paulo Freire's Intellectual Roots: Toward Historicity in Praxis. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 101–126. doi:10.5040/9781472553164.ch-006. ISBN 978-1-4411-1380-1. http://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/1002832/1fb090e71ce54337371cb171375ebda9.pdf. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- Luschei, Thomas F.; Soto-Peña, Michelle (2019). "Beyond Achievement: Colombia's Escuela Nueva and the Creation of Active Citizens". in Aman, Robert; Ireland, Timothy. Educational Alternatives in Latin America. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 113–141. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-53450-3_6. ISBN 978-3-319-53450-3. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-53450-3.pdf. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Mayo, Peter (1999). Gramsci, Freire, and Adult Education: Possibilities for Transformative Action. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-85649-614-8.

- ——— (2013). "The Gramscian Influence". in Lake, Robert; Kress, Tricia. Paulo Freire's Intellectual Roots: Toward Historicity in Praxis. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 53–64. doi:10.5040/9781472553164.ch-003. ISBN 978-1-4411-1380-1. http://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/1002832/1fb090e71ce54337371cb171375ebda9.pdf. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- McKenna, Brian (2013). "Paulo Freire's Blunt Challenge to Anthropology: Create a Pedagogy of the Oppressed for Your Times". Critique of Anthropology 33 (4): 447–475. doi:10.1177/0308275X13499383. ISSN 0308-275X.

- Ordóñez, Jacinto (1981). Paulo Freire's Concept of Freedom: A Philosophical Analysis (PhD dissertation). Chicago: Loyola University of Chicago. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- Peters, Michael A.; Besley, Tina (2015). "Introduction". in Peters, Michael A.; Besley, Tina. Paulo Freire: The Global Legacy. Counterpoints: Studies in the Postmodern Theory of Education. 500. New York: Peter Lang. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-1-4539-1408-3.

- Prodnik, Jernej Amon; Hamelink, Cees (2017). ""Well Friends, Let's Play Jazz": An Interview with Cees Hamelink". TripleC 15 (1): 262–284. doi:10.31269/triplec.v15i1.861. ISSN 1726-670X.

- Reynolds, William M. (2013). "Liberation Theology and Paulo Freire: On the Side of the Poor". in Lake, Robert; Kress, Tricia. Paulo Freire's Intellectual Roots: Toward Historicity in Praxis. New York: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 127–144. doi:10.5040/9781472553164.ch-007. ISBN 978-1-4411-1380-1. http://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/1002832/1fb090e71ce54337371cb171375ebda9.pdf. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- Rocha, Samuel D. (2018). "'Ser Mais': The Personalism of Paulo Freire". Philosophy of Education: 371–384. doi:10.47925/74.371. https://educationjournal.web.illinois.edu/ojs/index.php/pes/article/view/195. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Salas, Maria del Mar Ramis (2018). "Contributions of Freire's Theory to Dialogic Education". Social and Education History 7 (3): 277–299. doi:10.17583/hse.2018.3749. ISSN 2014-3567.

- Sriraman, Bharath (2008). "On the Origins of Social Justice: Darwin, Freire, Marx and Vivekananda". in Sriraman, Bharath. International Perspectives on Social Justice in Mathematics Education. The Montana Mathematics Enthusiast: Monograph Series in Mathematics Education. 1. Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age Publishing. pp. 1–6. ISBN 978-1-59311-880-8.

- Stone, Sandra J. (2013). "Ana Maria Araújo Freire: Scholar, Humanitarian, and Carrying on Paulo Freire's Legacy". in Kirylo, James D.. A Critical Pedagogy of Resistance. Transgressions. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers. pp. 45–47. doi:10.1007/978-94-6209-374-4_12. ISBN 978-94-6209-374-4.

Further reading

- Coben, Diana (1998). Radical Heroes: Gramsci, Freire and the Politics of Adult Education. New York: Garland Press.

- Darder, Antonia (2015). Freire and Education. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-53840-4.

- ——— (2017). Reinventing Paulo Freire: A Pedagogy of Love (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-67531-5.

- Elias, John (1994). Paulo Freire: Pedagogue of Liberation. Florida: Krieger.

- Ernest, Paul; Greer, Brian; Sriraman, Bharath, eds (2009). Critical Issues in Mathematics Education. The Montana Mathematics Enthusiast: Monograph Series in Mathematics Education. Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60752-039-9.

- Freire, Ana Maria Araújo; Vittoria, Paolo (2007). "Dialogue on Paulo Freire". Interamerican Journal of Education for Democracy 1 (1): 97–117. ISSN 1941-7799. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/ried/article/view/115/195. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Freire, Paulo, ed (1997). Mentoring the Mentor: A Critical Dialogue with Paulo Freire. Counterpoints: Studies in the Postmodern Theory of Education. 60. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-0-8204-3798-9.

- Gadotti, Moacir (1994). Reading Paulo Freire: His Life and Work. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1923-6.

- Gibson, Richard (1994). The Promethean Literacy: Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of Reading, Praxis and Liberation (dissertation). University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University. Archived from the original on 9 November 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Gottesman, Isaac (2016). The Critical Turn in Education: From Marxist Critique to Poststructuralist Feminism to Critical Theories of Race. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315769967. ISBN 978-1-315-76996-7.

- Kincheloe, Joe L. (2004). Critical Pedagogy Primer. New York: Peter Lang.

- Kirylo, James D.; Boyd, Drick (2017). Paulo Freire: His Faith, Spirituality, and Theology. Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers. doi:10.1007/978-94-6351-056-1. ISBN 978-94-6351-056-1.

- Mann, Bernhard, The Pedagogical and Political Concepts of Mahatma Gandhi and Paulo Freire. In: Claußen, B. (Ed.) International Studies in Political Socialization and ion. Bd. 8. Hamburg 1996. ISBN 3-926952-97-0

- McLaren, Peter (2000). Che Guevara, Paulo Freire and the Pedagogy of Revolution. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8476-9533-1.

- McLaren, Peter; Lankshear, Colin, eds (1994). Politics of Liberation: Paths from Freire. London: Routledge.

- McLaren, Peter; Leonard, Peter, eds (1993). Paulo Freire: A Critical Encounter. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-42026-3. https://libcom.org/files/peter-mclaren-paulo-freire-a-critical-encounter-1.pdf. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- Mayo, Peter (2004). Liberating Praxis: Paulo Freire's Legacy for Radical Education and Politics. Critical Studies in Education and Culture. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-89789-786-0.

- Morrow, Raymond A.; Torres, Carlos Alberto (2002). Reading Freire and Habermas: Critical Pedagogy and Transformative Social Change. New York: Teachers College Press. ISBN 978-0-8077-4202-0.

- O'Cadiz, Maria del Pilar; Wong, Pia Lindquist; Torres, Carlos Alberto (1997). Education and Democracy: Paulo Freire, Social Movements and Educational Reform in São Paulo. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press.

- Roberts, Peter (2000). Education, Literacy, and Humanization Exploring the Work of Paulo Freire. Westport, Connecticut: Bergin & Garvey.

- Rossatto, César Augusto (2005). Engaging Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of Possibility: From Blind to Transformative Optimism. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-7836-4.

- Schugurensky, Daniel (2011). Paulo Freire. London: Continuum.

- Taylor, Paul V. (1993). The Texts of Paulo Freire. Buckingham, England: Open University Press.

- Torres, Carlos Alberto (2014). First Freire: Early Writings in Social Justice Education. New York: Teachers College Press. ISBN 978-0-8077-5533-4.

- Vittoria, Paolo (2016). Narrating Paulo Freire: Toward a Pedagogy of Dialogue. London: IEPS Publisher.

External links

- Inquiry-Based Learning at Curlie

- Digital Library Paulo Freire (Pt-Br)

- Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire

- PopEd Toolkit - Exercises/Links inspired by Freire's work

- Interview with Maria Araújo Freire on her marriage to Paulo Freire

- A dialogue with Paulo Freire and Ira Shor (1988)

| Awards | ||

|---|---|---|

| New award | King Baudouin International Development Prize 1980–1981 With: Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research |

Succeeded by A. T. Ariyaratne |

| Preceded by Indar Jit Rikhye |

UNESCO Prize for Peace Education 1986 |

Succeeded by Laurence Deonna |

|

KSF

KSF