Plutarch of Athens

Topic: Biography

From HandWiki - Reading time: 3 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 3 min

Plutarch of Athens | |

|---|---|

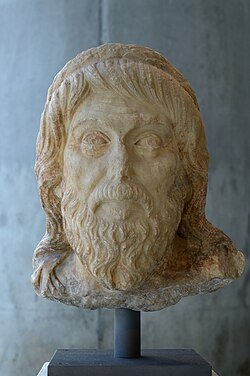

Portrait of a philosopher, early 5th century AD. The portrait most likely represents the Neo-Platonic philosopher Plutarch of Athens. Acropolis Museum Athens, Acr. 1313. | |

| Born | 350 AD |

| Died | 430 AD |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Neoplatonism |

| Notable students | Syrianus, Proclus |

Main interests | Platonism, Aristotelianism |

Influences

| |

Influenced

| |

Plutarch of Athens (Greek: Πλούταρχος ὁ Ἀθηναῖος; c. 350 – 430 AD) was a Greek philosopher and Neoplatonist who taught in Athens at the beginning of the 5th century. He reestablished the Platonic Academy there and became its leader. He wrote commentaries on Aristotle and Plato, emphasizing the doctrines which they had in common.

Life

He was the son of Nestorius and father of Hierius and Asclepigenia, who were his colleagues in the school. The origin of Neoplatonism in Athens is not known, but Plutarch is generally seen as the person who reestablished Plato's Academy in its Neoplatonist form. Plutarch and his followers (the "Platonic Succession") claimed to be the disciples of Iamblichus, and through him of Porphyry and Plotinus. Numbered among his disciples were Syrianus, who succeeded him as head of the school, and Proclus.

Philosophy

Plutarch's main principle was that the study of Aristotle must precede that of Plato, and like the Middle Platonists believed in the continuity between the two authors. With this object he wrote a commentary on Aristotle's On the Soul (De Anima) which was the most important contribution to Aristotelian literature since the time of Alexander of Aphrodisias; and a commentary on the Timaeus of Plato. His example was followed by Syrianus and others of the school. This critical spirit reached its greatest height in Proclus, the ablest exponent of this latter-day syncretism.

Plutarch was versed in all the theurgic traditions of the school, and believed, along with Iamblichus, in the possibility of attaining to communion with the Deity by the medium of the theurgic rites. Unlike the Alexandrists and the early Renaissance writers, he maintained that the soul which is bound up in the body by the ties of imagination and sensation does not perish with the corporeal media of sensation.

In psychology, while believing that Reason is the basis and foundation of all consciousness, he interposed between sensation and thought the faculty of Imagination, which, as distinct from both, is the activity of the soul under the stimulus of unceasing sensation. In other words, it provides the raw material for the operation of Reason. Reason is present in children as an inoperative potentiality, in adults as working upon the data of sensation and imagination, and, in its pure activity, it is the transcendental or pure intelligence of God.

References

- Suda, Domninos, Hegias, Nikolaos, Odainathos, Proklos o Lukios.

- Marinus, Vita Procli, 12.

- Photius, Bibliotheca, 242.

- Andron, Cosmin (2008), "Ploutarchos of Athens",The Routledge Encyclopedia of Ancient Natural Scientists, eds. Georgia Irby-Massie and Paul T. Keyser, Routledge.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Plutarch, of Athens". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Plutarch, of Athens". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

KSF

KSF