Slavoj Žižek

Topic: Biography

From HandWiki - Reading time: 24 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 24 min

Slavoj Žižek | |

|---|---|

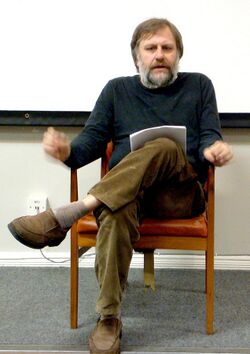

Žižek in Liverpool, England, 2008 | |

| Born | 21 March 1949 Ljubljana, PR Slovenia, FPR Yugoslavia |

| Education |

|

| Era | 20th-/21st-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School |

|

| Institutions | |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | Interpassivity Over-identification Ideology as an unconscious fantasy that structures reality Revival of dialectical materialism |

Slavoj Žižek (/ˈslɑːvɔɪ ˈʒiːʒɛk/ (![]() listen) SLAH-voy ZHEE-zhek; Slovene: [ˈslaʋɔj ˈʒiʒɛk]; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian philosopher, currently a researcher at the Department of Philosophy of the University of Ljubljana Faculty of Arts, and International director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities of the University of London.[2] He is also Global Eminent Scholar at Kyung Hee University in Seoul. He works in subjects including continental philosophy, political theory, cultural studies, psychoanalysis, film criticism, Marxism, Hegelianism and theology.

listen) SLAH-voy ZHEE-zhek; Slovene: [ˈslaʋɔj ˈʒiʒɛk]; born 21 March 1949) is a Slovenian philosopher, currently a researcher at the Department of Philosophy of the University of Ljubljana Faculty of Arts, and International director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities of the University of London.[2] He is also Global Eminent Scholar at Kyung Hee University in Seoul. He works in subjects including continental philosophy, political theory, cultural studies, psychoanalysis, film criticism, Marxism, Hegelianism and theology.

In 1989 Žižek published his first English-language text, The Sublime Object of Ideology, in which he departed from traditional Marxist theory to develop a materialist conception of ideology that drew heavily on Lacanian psychoanalysis and Hegelian idealism.[3][4] His theoretical work became increasingly eclectic and political in the 1990s, dealing frequently in the critical analysis of disparate forms of popular culture and making him a popular figure of the academic left.[3][5]

Žižek's idiosyncratic style, popular academic works, frequent magazine op-eds, and critical assimilation of high and low culture have gained him international influence, controversy, criticism and a substantial audience outside academia.[6][7][8][9][10] In 2012, Foreign Policy listed Žižek on its list of Top 100 Global Thinkers, calling him "a celebrity philosopher"[11] while elsewhere he has been dubbed the "Elvis of cultural theory"[12] and "the most dangerous philosopher in the West".[13] A 2005 documentary film entitled Zizek! chronicled Žižek's work. A journal, the International Journal of Žižek Studies, was founded by professors David J. Gunkel and Paul A. Taylor to engage with his work.[14][15]

Biography

Early life

Žižek was born in Ljubljana, SR Slovenia, Yugoslavia, into a middle-class family.[16] His father Jože Žižek was an economist and civil servant from the region of Prekmurje in eastern Slovenia. His mother Vesna, native of the Gorizia Hills in the Slovenian Littoral, was an accountant in a state enterprise. His parents were atheists.[17] He spent most of his childhood in the coastal town of Portorož, where he was exposed to Western film, theory and popular culture.[4][18] When Slavoj was a teenager his family moved back to Ljubljana where he attended Bežigrad High School.[18] In the 1960s and early 1970s, Slavoj encountered western philosophy in Zagreb. [citation needed]

Education

In 1967, during an era of liberalization in Titoist Yugoslavia, Žižek enrolled at the University of Ljubljana and studied philosophy and sociology.[19]

He had already begun reading French structuralists prior to entering university, and in 1967 he published the first translation of a text by Jacques Derrida into Slovenian.[20][20] Žižek frequented the circles of dissident intellectuals, including the Heideggerian philosophers Tine Hribar and Ivo Urbančič,[20] and published articles in alternative magazines, such as Praxis, Tribuna and Problemi, which he also edited.[18] In 1971 he accepted a job as an assistant researcher with the promise of tenure, but was dismissed after his Master's thesis was denounced by the authorities as being "non-Marxist".[21] He graduated from the University of Ljubljana in 1981 with a Doctor of Arts in Philosophy for his dissertation entitled The Theoretical and Practical Relevance of French Structuralism.[19]

He spent the next few years undertaking national service in the Yugoslav army in Karlovac.[19]

Career

During the 1980s, Žižek edited and translated Jacques Lacan, Sigmund Freud, and Louis Althusser.[22] He used Jacques Lacan's work to interpret Hegelian and Marxist philosophy.

In 1985, Žižek completed a second doctorate (Doctor of Philosophy in psychoanalysis) at the University of Paris VIII[19] under Jacques-Alain Miller and François Regnault.

He wrote the introduction to Slovene translations of G. K. Chesterton's and John Le Carré's detective novels.[23] In 1988, he published his first book dedicated entirely to film theory.[citation needed] He achieved international recognition as a social theorist with the 1989 publication of his first book in English, The Sublime Object of Ideology.[3][4]

Žižek has been publishing in journals such as Lacanian Ink and In These Times in the United States, the New Left Review and The London Review of Books in the United Kingdom, and with the Slovenian left-liberal magazine Mladina and newspapers Dnevnik and Delo. He also cooperates with the Polish leftist magazine Krytyka Polityczna, regional southeast European left-wing journal Novi Plamen, and serves on the editorial board of the psychoanalytical journal Problemi.[citation needed] Žižek is a series editor of the Northwestern University Press series Diaeresis that publishes works that "deal not only with philosophy, but also will intervene at the levels of ideology critique, politics, and art theory."[24]

Politics

In the late 1980s, Žižek came to public attention as a columnist for the alternative youth magazine Mladina, which was critical of Tito's policies, Yugoslav politics, especially the militarization of society. He was a member of the Communist Party of Slovenia until October 1988, when he quit in protest against the JBTZ trial together with 32 other Slovenian intellectuals.[25] Between 1988 and 1990, he was actively involved in several political and civil society movements which fought for the democratization of Slovenia, most notably the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights.[26] In the first free elections in 1990, he ran as the Liberal Democratic Party's candidate for the former four-person collective presidency of Slovenia.[3]

Despite his activity in liberal democratic projects, Žižek has remained committed to the communist ideal and has been critical of right-wing circles, such as nationalists, conservatives, and classical liberals both in Slovenia and worldwide. He wrote that the convention center in which nationalist Slovene writers hold their conventions should be blown up, adding, "Since we live in the time without any sense of irony, I must add I don't mean it literally."[27] Similarly, he jokingly made the following comment in May 2013, during Subversive Festival: "If they don't support SYRIZA, then, in my vision of the democratic future, all these people will get from me [is] a first-class one-way ticket to [a] gulag." In response, the right-wing New Democracy party claimed Žižek's comments should be understood literally, not ironically.[28][29]

In a 2008 interview with Amy Goodman on Democracy Now!, he described himself as a "communist in a qualified sense," and in another appearance in October 2009 he described himself as a "radical leftist."[30][31] The following year Žižek appeared in the Arte documentary Marx Reloaded in which he defended the idea of communism.[32]

In 2013, he corresponded with imprisoned Russian activist and Pussy Riot member Nadezhda Tolokonnikova.[33]

All hearts were beating for you as long as you were perceived as just another version of the liberal-democratic protest against the authoritarian state. The moment it became clear that you rejected global capitalism, reporting on Pussy Riot became much more ambiguous.

In 2016, during a conversation with Gary Younge at a Guardian Live event, Žižek endorsed Donald Trump for the US presidency in the 2016 election. He described Trump as a paradox, basically a centrist liberal in most of his positions, desperately trying to mask this by dirty jokes and stupidities.[34] In an opinion piece, published e.g. in Die Zeit, he described the then frontrunner candidate Hillary Clinton as the much less suitable alternative.[35] In an interview with the BBC, Žižek did however state that he thought Trump was "horrible" and his support would have been based on an attempt to encourage the Democratic Party to return to more leftist ideals.[36]

Just before the 2017 French presidential election, Žižek stated that one could not choose between Macron and Le Pen, arguing that the neoliberalism of Macron just gives rise to neofascism anyway. This was in response to many on the left calling for support for Macron to prevent a Le Pen victory.[37]

Public life

In 2003, Žižek wrote text to accompany Bruce Weber's photographs in a catalog for Abercrombie & Fitch. Questioned as to the seemliness of a major intellectual writing ad copy, Žižek told The Boston Globe, "If I were asked to choose between doing things like this to earn money and becoming fully employed as an American academic, kissing ass to get a tenured post, I would with pleasure choose writing for such journals!"[38]

Žižek and his thought have been the subject of several documentaries. The 1996 Liebe Dein Symptom wie Dich selbst! is a German documentary on him. In the 2004 The Reality of the Virtual, Žižek gave a one-hour lecture on his interpretation of Lacan's tripartite thesis of the imaginary, the symbolic, and the real.[citation needed] Zizek! is a 2005 documentary by Astra Taylor on his philosophy. The 2006 The Pervert's Guide to Cinema and 2012 The Pervert's Guide to Ideology also portray Žižek's ideas and cultural criticism. Examined Life (2008) features Žižek speaking about his conception of ecology at a garbage dump. He was also featured in the 2011 Marx Reloaded, directed by Jason Barker.[citation needed]

Foreign Policy named Žižek one of its 2012 Top 100 Global Thinkers "for giving voice to an era of absurdity."[11]

In 2019 Žižek began hosting a mini-series called How to Watch the News with Slavoj Žižek on the RT network.[39] In April, Žižek debated professor and psychologist Jordan Peterson at the Sony Centre in Toronto, Canada over happiness under capitalism versus Marxism.[40][41]

Personal life

Žižek has been married four times. His last wife is the Slovene journalist, columnist, and philosopher Jela Krečič, daughter of the architectural historian Peter Krečič.[42][43] He has a son.[44]

He is a fluent speaker of Slovene, Serbo-Croatian, French, German and English.[45]

Impact

His body of writing spans dense theoretical polemics, academic tomes, and accessible introductory books; in addition, he has taken part in various film projects, including two documentary collaborations with director Sophie Fiennes, The Pervert's Guide to Cinema (2006) and The Pervert's Guide to Ideology (2012). His work has impacted both academic and widespread public audiences (see for example his commentary in the 2003 Abercrombie and Fitch Quarterly).

Hundreds of academics have addressed aspects of Žižek's work in professional papers,[46] and in 2007, the International Journal of Žižek Studies was established for the discussion of his work.

Thought

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

(Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Ontology, ideology, and the Real

- Against Karl Marx's concept of ideology as described in The German Ideology, false consciousness prevents people from seeing how things really are. Building upon Althusser, ideology is thoroughly unconscious and functions as a series of justifications and spontaneous socio-symbolic rituals which support virtual authorities.

- The Real is not experienced as something which is ordered in a way that gives satisfactory meaning to all its parts in relation to one another. Instead the Real is experienced as through the lens of hegemonic systems of representation and reproduction, while resisting full inscription into the ordering system ascribed to it. This in turn may lead subjects to experience the Real as generating political resistance.

Drawing on Lacan's notion of the barred subject, the subject is a purely negative entity, a void of negativity (in the Hegelian sense), which allows for the flexibility and reflexivity of the Cartesian cogito (transcendental subject).[3][50] Though consciousness is opaque (following Hegel), the epistemological gap between the In-itself and For-itself is immanent to reality itself;.[51] The antinomies of Kant, quantum physics, and Alain Badiou's 'materialist' principle that 'The One is Not', point towards an inconsistent ("Barred") Real itself (that Lacan conceptualized prior).[52]

Although there are multiple Symbolic interpretations of the Real, they are not all relatively "true". Two instances of the Real can be identified: the abject Real (or "real Real"), which cannot be wholly integrated into the symbolic order, and the symbolic Real, a set of signifiers that can never be properly integrated into the horizon of sense of a subject. The truth is revealed in the process of transiting the contradictions; or the real is a "minimal difference", the gap between the infinite judgement of a reductionist materialism and experience as lived,[53] the "Parallax" of dialectical antagonisms are inherent to reality itself and dialectical materialism (contra Friedrich Engels) is a new materialist Hegelianism, incorporating the insights of Lacanian psychoanalysis, set theory, quantum physics, and contemporary continental philosophy.

Political thought and the postmodern subject

Žižek argues:

- The state is a system of regulatory institutions that shape our behavior. Its power is purely symbolic and has no normative force outside of collective behavior. In this way, the term the law signifies society's basic principles, which enable interaction by prohibiting certain acts.[54]

- Political decisions have become depoliticized and accepted as natural conclusions. For example, controversial policy decisions (such as reductions in social welfare spending) are presented as apparently "objective" necessities. Although governments make claims about increased citizen participation and democracy, the important decisions are still made in the interests of capital. The two-party system dominant in the United States and elsewhere produces a similar illusion.[55] It is still necessary to engage in particular conflicts – such as labor disputes – but the trick is to relate these individual events to the larger struggle. Particular demands, if executed well, might serve as metaphorical condensation for the system and its injustices. The real political conflict is between an ordered structure of society and those without a place in it.[56] In stark contrast to the intellectual tenets of the European "universalist Left" in general, and those Jürgen Habermas defined as postnational in particular, pro-sovereignty and pro-independence processes opened in Europe are good.[57]

- The postmodern subject is cynical toward official institutions, yet at the same time believes in conspiracies. When we lost our shared belief in a single power, we constructed another of the Other in order to escape the unbearable freedom that we faced.[58] It is not enough to merely know that you are being lied to, particularly when continuing to live a normal life under capitalism. For example, that despite people being aware of ideology, they may continue to act as automata, mistakenly believing that they are thereby expressing their radical freedom. Although one may possess a self-awareness, just because one understands what one is doing does not mean that one is doing the right thing.[59]

- Religion is not an enemy but rather one of the fields of struggle. Atheism is good. Religious fundamentalists are in a way no different from "godless Stalinist Communists". They both value divine will and salvation over moral or ethical action.[60][61]

Criticism

There are two main themes of critique of Žižek's ideas: his failure to articulate an alternative or program in the face of his denunciation of contemporary social, political, and economic arrangements, and his lack of rigor in argumentation.[62]

Ambiguity and unclear alternatives

Žižek's philosophical and political positions are not always clearly understandable, and his work has been criticized for a failure to take a consistent stance.[63] While he has claimed to stand by a revolutionary Marxist project, his lack of vision concerning the possible circumstances which could lead to successful revolution makes it unclear what that project consists of. According to John Gray and John Holbo, his theoretical argument often lacks grounding in historical fact, which makes him more provocative than insightful.[62][64][65]

Roger Scruton has written in "Fools, Frauds and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left", "To summarize Žižek's position is not easy: he slips between philosophical and psychoanalytical ways of arguing, and is spell-bound by Lacan's gnomic utterances. He is a lover of paradox, and believes strongly in what Hegel called 'the labour of the negative' though taking the idea, as always, one stage further towards the brick wall of paradox".[66]

Žižek's refusal to present an alternative vision has led critics to accuse him of using unsustainable Marxist categories of analysis and having a 19th-century understanding of class.[67] For example, Ernesto Laclau argued that "Žižek uses class as a sort of deus ex machina to play the role of the good guy against the multicultural devils."[68] The use of such analysis, however, is not systematic and draws on critical accounts of Stalinism and Maoism, as well as post-structuralism and Lacanian psychoanalysis.[69]

Žižek does not agree with critics who claim he believes in a historical necessity:

There is no such thing as the Communist big Other, there's no historical necessity or teleology directing and guiding our actions. (In Slovene: "Ni komunističnega velikega Drugega, nobene zgodovinske nujnosti ali teleologije, ki bi usmerjala in vodila naša dejanja".)[27]

In his book Living in the End Times, Žižek suggests that the criticism of his positions is itself ambiguous and multilateral:

[...] I am attacked for being anti-Semitic and for spreading Zionist lies, for being a covert Slovene nationalist and unpatriotic traitor to my nation, for being a crypto-Stalinist defending terror and for spreading Bourgeois lies about Communism... so maybe, just maybe I am on right path, the path of fidelity to freedom."[70]

Heterodox style and scholarship

Critics complain of a theoretical chaos in which questions and answers are confused and in which Žižek constantly recycles old ideas which were scientifically refuted long ago or which in reality have quite a different meaning than Žižek gives to them.[71] Harpham calls Žižek's style "a stream of nonconsecutive units arranged in arbitrary sequences that solicit a sporadic and discontinuous attention."[72] O'Neill concurs: "a dizzying array of wildly entertaining and often quite maddening rhetorical strategies are deployed in order to beguile, browbeat, dumbfound, dazzle, confuse, mislead, overwhelm, and generally subdue the reader into acceptance."[73]

Such presentation has laid him open to accusations of misreading other philosophers, particularly Jacques Lacan and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Žižek carries over many concepts from Lacan's teachings into the sphere of political and social theory, but has a tendency to do so in an extreme deviation from its psychoanalytic context.[74] Similarly, according to some critics, Žižek's conflation of Lacan's unconscious with Hegel's unconscious is mistaken. Noah Horwitz, in an effort to dissociate Lacan from Hegel, interprets the Lacanian unconscious and the Hegelian unconscious as two totally different mechanisms. Horwitz points out, in Lacan and Hegel's differing approaches to the topic of speech, that Lacan's unconscious reveals itself to us in parapraxis, or "slips-of-the-tongue". We are therefore, according to Lacan, alienated from language through the revelation of our desire (even if that desire originated with the Other, as he claims, it remains peculiar to us). In Hegel's unconscious, however, we are alienated from language whenever we attempt to articulate a particular and end up articulating a universal. For example, if I say 'the dog is with me', although I am trying to say something about this particular dog at this particular time, I actually produce the universal category 'dog', and therefore express a generality, not the particularity I desire. Hegel's argument implies that, at the level of sense-certainty, we can never express the true nature of reality. Lacan's argument implies, to the contrary, that speech reveals the true structure of a particular unconscious mind.[75]

In a very negative review of Žižek's book Less than Nothing, the British political philosopher John Gray attacked Žižek for his celebrations of violence, his failure to ground his theories in historical facts, and his ‘formless radicalism’ which, according to Gray, professes to be communist yet lacks the conviction that communism could ever be successfully realized. Gray concluded that Žižek's work, though entertaining, is intellectually worthless: "Achieving a deceptive substance by endlessly reiterating an essentially empty vision, Žižek's work amounts in the end to less than nothing."[62]

Accusations of self-plagiarism in 2014

Žižek's tendency to recycle portions of his own texts in subsequent works resulted in the accusation of self-plagiarism by The New York Times in 2014, after Žižek published an op-ed in the magazine which contained portions of his writing from an earlier book.[76] In response, Žižek expressed perplexity at the harsh tone of the denunciation, emphasizing that the recycled passages in question only acted as references from his theoretical books to supplement otherwise original writing.[76]

On 11 July 2014, American weekly newsmagazine Newsweek reported that in an article published in 2006 Žižek plagiarized substantial passages from an earlier review that first appeared in the journal American Renaissance, a publication condemned by the Southern Poverty Law Center as the organ of a "white nationalist hate group."[77] However, in response to the allegations, Žižek stated:

When I was writing the text on Derrida which contains the problematic passages, a friend told me about Kevin Macdonald's theories, and I asked him to send me a brief resume. The friend send [sic] it to me, assuring me that I can use it freely since it merely resumes another's line of thought. Consequently, I did just that – and I sincerely apologize for not knowing that my friend's resume was largely borrowed from Stanley Hornbeck's review of Macdonald's book. [...] As any reader can quickly establish, the problematic passages are purely informative, a report on another's theory for which I have no affinity whatsoever; all I do after this brief resume is quickly dismissing Macdonald's theory as a new chapter in the long process of the destruction of Reason. In no way can I thus be accused of plagiarizing another's line of thought, of "stealing ideas". I nonetheless deeply regret the incident.[78]

Chomsky

Noam Chomsky is critical of Žižek, saying that he is guilty of "using fancy terms like polysyllables and pretending you have a theory when you have no theory whatsoever", and also that Žižek’s theories never go "beyond the level of something you can explain in five minutes to a twelve-year-old".[79]

Published works

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Liebe Dein Symptom wie Dich selbst! | Lecturer (as himself) |

| 2004 | The Reality of the Virtual | Script author, lecturer (as himself) |

| 2005 | Zizek! | Lecturer (as himself) |

| 2006 | The Pervert's Guide to Cinema | Screenwriter, presenter (as himself) |

| 2012 | The Pervert's Guide to Ideology | Screenwriter, presenter (as himself) |

| 2016 | Houston, We Have a Problem! | As himself |

| 2018 | Turn On (The Mute Series)[80] | Based on an idea by Slavoj Žižek |

Bibliography

Žižek is a prolific writer and has published in numerous languages.

References

Citations

- ↑ Bostjan Nedoh (ed.), Lacan and Deleuze: A Disjunctive Synthesis, Edinburgh University Press, 2016, p. 193: "Žižek is convinced that post-Hegelian psychoanalytic drive theory is both compatible with and even integral to a Hegelianism reinvented for the twenty-first century."

- ↑ "Slavoj Zizek - International Director — The Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities, Birkbeck, University of London". http://www.bbk.ac.uk/bih/aboutus/staff/zizek.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Slavoj Zizek - Slovene philosopher and cultural theorist". http://www.britannica.com/biography/Slavoj-Zizek.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Slavoj Žižek," by Matthew Sharpe, The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ISSN 2161-0002, http://www.iep.utm.edu/zizek/. 27 September 2015.

- ↑ Kirk Boyle. "The Four Fundamental Concepts of Slavoj Žižek's Psychoanalytic Marxism." International Journal of Žižek Studies. Vol 2.1. (link)

- ↑ Germany, SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg. "SPIEGEL Interview with Slavoj Zizek: 'The Greatest Threat to Europe Is Its Inertia'". http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/slavoj-zizek-greatest-threat-to-europe-is-it-s-inertia-a-1023506.html.

- ↑ "Slavoj Zizek: the world's hippest philosopher". https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/authorinterviews/7871302/Slavoj-Zizek-the-worlds-hippest-philosopher.html.

- ↑ Engelhart, Katie. "Slavoj Zizek: I am not the world's hippest philosopher!". http://www.salon.com/2012/12/29/slavoj_zizek_i_am_not_the_worlds_hippest_philosopher/.

- ↑ O'Hagan, Sean (13 January 2013). "Slavoj Žižek: a philosopher to sing about". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2013/jan/13/observer-profile-slavoj-zizek-opera/. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ↑ "Žižek – The most dangerous thinker in the west?". 23 September 2010. https://ceasefiremagazine.co.uk/zizek-the-most-dangerous-thinker-in-the-west/.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "The FP Top 100 Global Thinkers". Foreign Policy. 26 November 2012. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20121130221322/http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2012/11/26/the_fp_100_global_thinkers?page=0,33. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ "International Journal of Žižek Studies, home page". http://zizekstudies.org/index.php/ijzs/index. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ↑ "Slavoj Zizek - VICE - United Kingdom". https://www.vice.com/en_uk/video/slavoj-zizek.

- ↑ "About the Journal". http://zizekstudies.org/index.php/IJZS/about/editorialPolicies#focusAndScope. "The International Journal of Žižek Studies (IJŽS) is an online, peer-reviewed academic journal devoted to investigating, elaborating, and critiquing the work of Slavoj Žižek."

- ↑ "Žižek Studies" (in en). 31 October 2019. https://www.peterlang.com/view/title/65200?tab=aboutauthor. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ↑ "Kdo je kdaj: Slavoj Žižek. Tisti poslednji marksist, ki je iz filozofije naredil pop in iz popa filozofijo" (in Slovenian). Mladina. 24 October 2004. http://www.mladina.si/tednik/200442/clanek/nar-kdo_je_kdaj--ursa_matos/. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ↑ Slovenski biografski leksikon (Ljubljana: SAZU, 1991), XV. edition

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Slovenska pomlad: Slavoj Žižek (Webpage run by the National Museum of Modern History in Ljubljana)". Slovenskapomlad.si. 29 September 1988. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111003180230/http://www.slovenskapomlad.si/2?id=20. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Tony Meyers Slavoj Zizek - His Life lacan.com, from: Slavoj Zizek, London: Routledge, 2003.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "Tednik, številka 42, Slavoj Žižek". Mladina.Si. 24 October 2004. http://www.mladina.si/tednik/200442/clanek/nar-kdo_je_kdaj--ursa_matos/. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ↑ Žižek's response to the article "Če sem v kaj resnično zaljubljena, sem v življenje Sobotna priloga Dela, p. 37 (19.1. 2008)

- ↑ "Prevajalci – Društvo slovenskih književnih prevajalcev". Dskp-drustvo.si. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120105042135/http://www.dskp-drustvo.si/prevajalci.php. Retrieved 7 January 2012.

- ↑ Sean Sheehan (2012). Zizek: A Guide for the Perplexed. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 10. ISBN 978-1441180872. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=TsDgpEkMGdcC&pg=PA10&lpg=PA10.

- ↑ "Diaeresis series page". Northwestern University Press. http://www.nupress.northwestern.edu/content/diaeresis. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- ↑ "Skupinski protestni izstop iz ZKS". Slovenska Pomlad. 28 October 1998. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111003180147/http://www.slovenskapomlad.si/1?id=103.

- ↑ Odbor za varstvo človekovih pravic. Slovenska Pomlad. 3 June 1998. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111003180306/http://www.slovenskapomlad.si/1?id=31&aofs=3.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Interview with Žižek – part two, Delo, 2 March 2013.

- ↑ Sabby Mionis (6 March 2012). "Israel must fight to keep neo-Nazis out of Greece's government". Haaretz. http://www.haaretz.com/opinion/israel-must-fight-to-keep-neo-nazis-out-of-greece-s-government-1.416802. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ "Slovenian philosopher Zizek proposes 'gulag' for those who do not support SYRIZA". 20 May 2013. http://www.ekathimerini.com/4dcgi/_w_articles_wsite1_1_20/05/2013_499789. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ↑ Democracy Now! television program online transcript, 11 March 2008.

- ↑ "Slovenian Philosopher Slavoj Zizek on Capitalism, Healthcare, Latin American "Populism" and the "Farcical" Financial Crisis". Democracynow.org. http://www.democracynow.org/2009/10/15/slovenian_philosopher_slavoj_zizek_on_the. Retrieved 13 August 2010.

- ↑ "Marx Reloaded and the revolutionary turn | BTURN" (in en-US). http://bturn.com/10228/marx-reloaded-and-the-revolutionary-turn.

- ↑ "Nadezhda Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot's prison letters to Slavoj Žižek". https://www.theguardian.com/music/2013/nov/15/pussy-riot-nadezhda-tolokonnikova-slavoj-zizek.

- ↑ Browne, Marcus (28 April 2016). "Slavoj Žižek: 'Trump is really a centrist liberal'". The Gurdfian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/apr/28/slavoj-zizek-donald-trump-is-really-a-centrist-liberal.

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj (6 November 2016). "Die schlimme Wohlfühlwahl Trump ist abstoßend. Was ist noch abstoßender? Der wirtschaftshörige und aggressive Konsens, für den Hillary Clinton steht.". DIE ZEIT Nr. 45/2016. http://www.zeit.de/2016/45/hillary-clinton-donald-trump-positionierung-us-wahl.

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj. "Slavoj Zizek on Trump and Brexit - BBC News". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ZUCemb2plE.

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj (3 May 2017). "Don’t Believe the Liberals – There Is No Real Choice between Le Pen and Macron." TheIndependent.co.UK. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ↑ Glenn, Joshua. "The Examined Life: Enjoy Your Chinos!", The Boston Globe. 6 July 2003. H2.

- ↑ "How to Watch the News with Slavoj Žižek". https://www.rt.com/shows/how-watch-news-with-slavoj-zizek/. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ↑ Raju Mudhar; Brendan Kennedy (April 19, 2019). "Jordan Peterson, Slavoj Zizek each draw fans at sold-out debate". Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2019/04/19/jordan-peterson-slavoj-zizek-each-draw-fans-at-sold-out-debate.html.

- ↑ Stephen Marche (April 20, 2019). "The 'debate of the century': what happened when Jordan Peterson debated Slavoj Žižek". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/apr/20/jordan-peterson-slavoj-zizek-happiness-capitalism-marxism.

- ↑ "Žižka vzela Jela z Dela". Delo. 1 July 2013. http://www.delo.si/druzba/panorama/zizka-vzela-jela-z-dela.html. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ "Philosopher and Beauty". Delo. 29 March 2005. http://www.delo.si/clanek/8516. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- ↑ Forster, Katie (10 December 2016). "Interview: Slavoj Žižek: ‘We are all basically evil, egotistical, disgusting’." TheGuardian.com. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ Ippolit Belinski (30 June 2017). "Slavoj Žižek - A plea for bureaucratic socialism (June 2017)." Youtube.com. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ "Google Scholar search for Zizek". Google Scholar. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?num=50&hl=en&lr=&c2coff=1&q=slavoj+zizek&btnG=Search. Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj. The Sublime Object of Ideology. New York: Verso, 1989.

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj (2012-05-22). Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism. Verso Books. ISBN 9781844678976. https://books.google.com/books?id=XxYQCoaEU7AC.

- ↑ Zizek, Slavoj (2014-10-07). Absolute Recoil: Towards A New Foundation Of Dialectical Materialism. Verso Books. ISBN 9781781686836. https://books.google.com/books?id=i8xNBAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Sinnerbrink, Robert (2008). "The Hegelian 'Night of the World': Žižek on Subjectivity, Negativity, and Universality". International Journal of Žižek Studies 2 (2). ISSN 1751-8229. http://zizekstudies.org/index.php/ijzs/article/view/136. Retrieved 17 August 2012. "This extraordinary analysis of the transcendental imagination, critique of Heidegger, and rereading of Hegelian 'night of the world,' together contribute to a reassertion of the radicality of the 'Cartesian subject'—that thoroughly repudiated theoretical spectre which nonetheless continues to 'haunt Western academia' (1999: 1–5). This unorthodox reading of the Hegelian 'night of the world'—the radical negativity that haunts subjectivity—is developed further in an explicitly political direction, which helps explain a critique of the 'Fukuyamaian' consensus, shared both by moral-religious conservatives and libertarian 'postmodernists', that global capitalism remains the 'unsurpassable horizon of our times'.".

- ↑ Eyers, Tom; Harman, Graham; Johnston, Adrian; Gaufey, Guy Le; McGowan, Todd; Rousselle, Duane; Riha, Jelica Šumič; Riha, Rado (2013-01-01). Umbr(a): The Object. Umbr(a) Journal. ISBN 9780979953965. https://books.google.com/books?id=k7QbBAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Zizek, Slavoj (2012-05-22). Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism. Verso Books. ISBN 9781844679027. https://books.google.com/books?id=FAqM5rxWWKwC.

- ↑ Zizek, On Belief

- ↑ Žižek, For They Know Not What They Do

- ↑ A Plea for Intolerance

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj (1999). "Political Subjectivization and Its Vicissitudes". The Ticklish Subject: the absent centre of political ontology. London: Verso. ISBN 9781859848944.

- ↑ Žižek: "The force of universalism is in you Basques, not in the Spanish state", Interview in ARGIA (27 June 2010)

- ↑ Žižek, Looking Awry: an Introduction to Jacques Lacan through Popular Culture

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj (18 March 1999). "You May!". London Review of Books 21 (6). http://www.lrb.co.uk/v21/n06/slavoj-zizek/you-may. Retrieved 20 August 2012. "But the notion is undermined by the rise of what might be called 'Post-Modern racism', the surprising characteristic of which is its insensitivity to reflection – a neo-Nazi skinhead who beats up black people knows what he's doing, but does it anyway. Reflexivisation has transformed the structure of social dominance. Take the public image of Bill Gates....".

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj. "Atheism is a legacy worth fighting for". The New York Times. 13 March 2006.

- ↑ Zizek, Slavoj. "Atheism is a Legacy Worth Fighting For". News.Genius.com. Retrieved Mon., 18 August 2014.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Gray, John (12 July 2012). "The Violent Visions of Slavoj Žižek". New York Review of Books. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2012/jul/12/violent-visions-slavoj-zizek/. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ↑ Kuhn, Gabriel (2011). The Anarchist Hypothesis, or Badiou, Žižek, and the Anti-Anarchist Prejudice Alpine Anarchist. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- ↑ Holbo, John (1 January 2004). "On Žižek and Trilling". Philosophy and Literature 28 (2): 430–440. doi:10.1353/phl.2004.0029. "...an unhealthy anti-liberal is one, like Z+iz=ek, who ticks and tocks in unreflective revulsion at liberalism, pantomiming that he is de Maistre (or Abraham) or Robespierre (or Lenin) by turns, lest he look like Mill.".

- ↑ Holbo, John (17 December 2010). "Zizek on the Financial Collapse – and Liberalism". Crooked Timbers. http://crookedtimber.org/2010/12/17/zizek-on-the-financial-collapse-and-liberalism/. Retrieved 21 August 2012. "To review: Zizek does this liberal = neoliberal thing. Which is no good. And he doesn't even have much to say about economics. And Zizek does this liberal = self-hating pc white intellectuals thing. Which is no good."

- ↑ Scruton, Roger (2015). Fools, Frauds and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left. Bloomsbury. p. 256. ISBN 1408187337.

- ↑ Žižek, Slavoj (July 3, 2012). "Slavoj Zizek responds to his critics". Jacobin. https://www.jacobinmag.com/2012/07/slavoj-zizek-responds-to-his-critics/. Retrieved 13 April 2018.

- ↑ Butler, Judith, Ernesto Laclau and Slavoj Žižek Contingency, Hegemony, Universality: Contemporary Dialogues on the Left. Verso. London, New York City 2000. pp. 202–206

- ↑ Bill Van Auken; Adam Haig (12 November 2010). "Zizek in Manhattan: An intellectual charlatan masquerading as "left"". World Socialist Web Site. http://www.wsws.org/articles/2010/nov2010/zize-n12.shtml. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ Slavoj Žižek. "Living in the End Times".

- ↑ See e.g. David Bordwell, "Slavoj Žižek: Say Anything", DavidBordwell.net blog, April 2005.[1]; Philipp Oehmke, "Welcome to the Slavoj Zizek Show". Der Spiegel Online (International edition), 7 August 2010 [2]; Jonathan Rée, "Less Than Nothing by Slavoj Žižek – review. A march through Slavoj Žižek's 'masterwork'". The Guardian, 27 June 2012.[3]

- ↑ Harpham "Doing the Impossible: Slavoj Žižek and the End of Knowledge"

- ↑ O'Neill, "The Last Analysis of Slavoj Žižek"

- ↑ Ian Parker, Slavoj Žižek: A Critical Introduction (Pluto Press: London and Sterling, 2004) p.78-80. For example, Žižek's appropriation of Lacan's discussion of Antigone in his 1959/1960 seminar, The Ethics of Psychoanalysis. In this seminar, Lacan uses Antigone to defend the claim that "the only thing of which one can be guilty is of having given ground relative to one's desire" (Slavoj Žižek, The Metastases of Enjoyment, Verso: London, 1994; p. 69). However, as Parker notes, Antigone's act (burying her dead brother in the knowledge that she will be buried alive) was never intended to effect a revolutionary change in the political status quo; yet, despite this, Žižek frequently cites Antigone as a paradigm of ethico-political action.

- ↑ Noah Horwitz, "Contra the Slovenians: Returning to Lacan and away from Hegel" (Philosophy Today, Spring 2005, pp. 24–32.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "Slavoj Žižek On 'Self Plagiarism' in The New York Times: What's the Big Deal?". 10 September 2014. http://www.newsweek.com/slavoj-zizek-self-plagiarized-new-york-times-269221.

- ↑ "Did Marxist Philosophy Superstar Slavoj Žižek Plagiarize a White Nationalist Journal?". Newsweek. 11 July 2014. http://www.newsweek.com/did-marxist-philosophy-superstar-slavoj-zizek-plagiarize-white-nationalist-journal-258433. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ↑ Dean, Michelle. "Slavoj Žižek Sorta Kinda Admits Plagiarizing White Supremacist Journal". Gawker Online. http://gawker.com/slavoj-zizek-sorta-kinda-admits-plagiarizing-white-supr-1604590014. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ↑ Springer, Mike (28 June 2013). "Noam Chomsky Slams Žižek and Lacan: Empty 'Posturing'", OpenCulture.com, Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ↑ "TURN ON — from The MUTE Series". http://www.muteseries.com/films/turn_on.php.

Works cited

- Canning, P. "The Sublime Theorist of Slovenia: Peter Canning Interviews Slavoj Žižek" in Artforum, Issue 31, March 1993, pp. 84–9.

- Sharpe, Matthew, Slavoj Žižek: A Little Piece of the Real, Hants: Ashgate, 2004.

- Parker, Ian, Slavoj Žižek: A Critical Introduction, London: Pluto Press, 2004.

- Butler, Rex, Slavoj Žižek: Live Theory, London: Continuum, 2004.

- Kay, Sarah, Žižek: A Critical Introduction, London: Polity, 2003.

- Myers, Tony, Slavoj Žižek (Routledge Critical Thinkers)London: Routledge, 2003.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Slavoj Žižek. |

- Slavoj Žižek at Curlie

- Slavoj Žižek on Big Think

- Slavoj Žižek Faculty Page at European Graduate School

- Žižek's entry in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Žižek bibliography at Lacanian Ink magazine

- Column archive at The Guardian

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Slavoj Žižek on Charlie Rose

- Slavoj Žižek on IMDb

- Wendy Brown, Costas Douzinas, Stephen Frosh, and Zizek at the London Critical Theory Summer School – Friday Debate 2012

KSF

KSF