Bacterial growth

Topic: Biology

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

Bacterial growth[1] is proliferation of bacterium into two daughter cells, in a process called binary fission. Providing no mutation event occurs, the resulting daughter cells are genetically identical to the original cell. Hence, bacterial growth occurs. Both daughter cells from the division do not necessarily survive. However, if the surviving number exceeds unity on average, the bacterial population undergoes exponential growth. The measurement of an exponential bacterial growth curve in batch culture was traditionally a part of the training of all microbiologists; the basic means requires bacterial enumeration (cell counting) by direct and individual (microscopic, flow cytometry[2]), direct and bulk (biomass), indirect and individual (colony counting), or indirect and bulk (most probable number, turbidity, nutrient uptake) methods. Models reconcile theory with the measurements.[3]

Phases

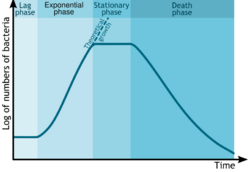

In autecological studies, the growth of bacteria (or other microorganisms, as protozoa, microalgae or yeasts) in batch culture can be modeled with four different phases: lag phase (A), log phase or exponential phase (B), stationary phase (C), and death phase (D).[4]

- During lag phase, bacteria adapt themselves to growth conditions. It is the period where the individual bacteria are maturing and not yet able to divide. During the lag phase of the bacterial growth cycle, the synthesis of RNA, enzymes and other molecules occurs. During the lag phase cells change very little because the cells do not immediately reproduce in a new medium. This period of little to no cell division is called the lag phase and can last for 1 hour to several days. During this phase cells are not dormant.[5]

- The log phase (sometimes called the logarithmic phase or the exponential phase) is a period characterized by cell doubling.[6] The number of new bacteria appearing per unit time is proportional to the present population. If growth is not limited, doubling will continue at a constant rate so both the number of cells and the rate of population increase doubles with each consecutive time period. For this type of exponential growth, plotting the natural logarithm of cell number against time produces a straight line. The slope of this line is the specific growth rate of the organism, which is a measure of the number of divisions per cell per unit time.[6] The actual rate of this growth (i.e. the slope of the line in the figure) depends upon the growth conditions, which affect the frequency of cell division events and the probability of both daughter cells surviving. Under controlled conditions, cyanobacteria can double their population four times a day and then they can triple their population.[7] Exponential growth cannot continue indefinitely, however, because the medium is soon depleted of nutrients and enriched with wastes.

- The stationary phase is often due to a growth-limiting factor such as the depletion of an essential nutrient, and/or the formation of an inhibitory product such as an organic acid. Stationary phase results from a situation in which growth rate and death rate are equal. The number of new cells created is limited by the growth factor and as a result the rate of cell growth matches the rate of cell death. The result is a “smooth,” horizontal linear part of the curve during the stationary phase. Mutations can occur during stationary phase. Bridges et al. (2001)[8] presented evidence that DNA damage is responsible for many of the mutations arising in the genomes of stationary phase or starving bacteria. Endogenously generated reactive oxygen species appear to be a major source of such damages.[8] Bacteria in this phase sometimes enter dormancy, using hibernation factors to slow their metabolism.[9]

- At death phase (decline phase), bacteria die. This could be caused by lack of nutrients, environmental temperature above or below the tolerance band for the species, or other injurious conditions.

This basic batch culture growth model draws out and emphasizes aspects of bacterial growth which may differ from the growth of macrofauna. It emphasizes clonality, asexual binary division, the short development time relative to replication itself, the seemingly low death rate, the need to move from a dormant state to a reproductive state or to condition the media, and finally, the tendency of lab adapted strains to exhaust their nutrients. In reality, even in batch culture, the four phases are not well defined. The cells do not reproduce in synchrony without explicit and continual prompting (as in experiments with stalked bacteria [10]) and their exponential phase growth is often not ever a constant rate, but instead a slowly decaying rate, a constant stochastic response to pressures both to reproduce and to go dormant in the face of declining nutrient concentrations and increasing waste concentrations.

The decrease in number of bacteria may even become logarithmic. Hence, this phase of growth may also be called as negative logarithmic or negative exponential growth phase.[1]

Near the end of the logarithmic phase of a batch culture, competence for natural genetic transformation may be induced, as in Bacillus subtilis[11] and in other bacteria. Natural genetic transformation is a form of DNA transfer that appears to be an adaptation for repairing DNA damages.

Batch culture is the most common laboratory growth method in which bacterial growth is studied, but it is only one of many. It is ideally spatially unstructured and temporally structured. The bacterial culture is incubated in a closed vessel with a single batch of medium. In some experimental regimes, some of the bacterial culture is periodically removed and added to fresh sterile medium. In the extreme case, this leads to the continual renewal of the nutrients. This is a chemostat, also known as continuous culture. It is ideally spatially unstructured and temporally unstructured, in a steady state defined by the rates of nutrient supply and bacterial growth. In comparison to batch culture, bacteria are maintained in exponential growth phase, and the growth rate of the bacteria is known. Related devices include turbidostats and auxostats. When Escherichia coli is growing very slowly with a doubling time of 16 hours in a chemostat most cells have a single chromosome.[2]

Bacterial growth can be suppressed with bacteriostats, without necessarily killing the bacteria. Certain toxins can be used to suppress bacterial growth or kill bacteria. Antibiotics (or, more properly, antibacterial drugs) are drugs used to kill bacteria; they can have side effects or even cause adverse reactions in people, however they are not classified as toxins. In a synecological, true-to-nature situation in which more than one bacterial species is present, the growth of microbes is more dynamic and continual.

Liquid is not the only laboratory environment for bacterial growth. Spatially structured environments such as biofilms or agar surfaces present additional complex growth models.

The 5th phase: Long-term stationary phase

Long-term stationary phase, unlike early stationary phase (in which there is little cell division), is a highly dynamic period in which the birth and death rates are balanced. It's been proven that after death phase E. coli can be maintained in batch culture for long periods without adding nutrients.[12][13] By providing sterile distilled water to maintain volume and osmolarity, aerobically grown cultures can be maintained at densities of ~106 colony-forming units (CFUs) per ml for more than 5 years without the addition of nutrients in batch culture.[14]

Environmental conditions

Environmental factors influence rate of bacterial growth such as acidity (pH), temperature, water activity, macro and micro nutrients, oxygen levels, and toxins. Conditions tend to be relatively consistent between bacteria with the exception of extremophiles. Bacterium have optimal growth conditions under which they thrive, but once outside of those conditions the stress can result in either reduced or stalled growth, dormancy (such as formation spores), or death. Maintaining sub-optimal growth conditions is a key principle to food preservation.

Temperature

Low temperatures tend to reduce growth rates which has led to refrigeration being instrumental in food preservation. Depending on temperature, bacteria can be classified as:

- Psychrophiles

Psychrophiles are extremophilic cold-loving bacteria or archaea with an optimal temperature for growth at about 15°C or lower (maximal temperature for growth at 20°C, minimal temperature for growth at 0°C or lower). Psychrophiles are typically found in Earth's extremely cold ecosystems, such as polar ice-cap regions, permafrost, polar surface, and deep oceans.[15]

- Mesophiles

Mesophiles are bacteria that thrive at moderate temperatures, growing best between 20 and 45°C. These temperatures align with the natural body temperatures of humans, which is why many human pathogens are mesophiles.[16]

- Thermophiles

Thrive under temperatures from 45 to more than 100°C.[17]

Acidity

Optimal acidity for bacteria tends to be around pH 6.5 to 7.0 (neutral), those living in lesser pH being acidophiles and higher alkalophiles. Some bacteria can change the pH such as by excreting acid resulting in sub-optimal conditions.[18]

Water activity

Oxygen

Bacteria can be aerobes or anaerobes. Depending on the degree of oxygen required bacteria can fall into the following classes:

- facultative-anaerobes-ie aerotolerant absence or minimal oxygen required for their growth

- obligate-anaerobes grow only in complete absence of oxygen

- facultative aerobes-can grow either in presence or minimal oxygen

- obligate aerobes-grow only in the presence of oxygen

Micronutrients

Ample nutrients

Toxic compounds

Toxic compounds such as ethanol can hinder growth or kill bacteria. This is used beneficially for disinfection and in food preservation.

See also

References

- ↑ "Microbial Primer: Bacterial growth kinetics". Microbiology 170 (2): 001428. February 2024. doi:10.1099/mic.0.001428. PMID 38329407.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Cell cycle parameters of slowly growing Escherichia coli B/r studied by flow cytometry". J. Bacteriol. 154 (2): 656–62. 1983. doi:10.1128/jb.154.2.656-662.1983. PMID 6341358.

- ↑ "Modeling of the Bacterial Growth Curve". Applied and Environmental Microbiology 56 (6): 1875–1881. 1990. doi:10.1128/aem.56.6.1875-1881.1990. PMID 16348228. Bibcode: 1990ApEnM..56.1875Z.

- ↑ "Bacterial Growth Curve". University of Cincinnati Clermont College. 17 July 2004. http://biology.clc.uc.edu/fankhauser/labs/microbiology/growth_curve/growth_curve.htm.

- ↑ Microbiology An Introduction (Tenth ed.). Pearson Benjamin Cummings. 2010. ISBN 978-0-321-55007-1.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Bacterial Growth". BACANOVA project. European Commission. http://www.ifr.ac.uk/bacanova/project_backg.html.

- ↑ "Marshall T. Savage - An Exponentialist View". Famous Exponentialists. Exponentialist homepage. 15 December 2011. http://members.optusnet.com.au/exponentialist/Savage.htm.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Effect of endogenous carotenoids on "adaptive" mutation in Escherichia coli FC40". Mutat. Res. 473 (1): 109–19. 2001. doi:10.1016/s0027-5107(00)00144-5. PMID 11166030. Bibcode: 2001MRFMM.473..109B.

- ↑ Samorodnitsky, Dan (2024-06-05). "Most Life on Earth is Dormant, After Pulling an 'Emergency Brake'" (in en). https://www.quantamagazine.org/most-life-on-earth-is-dormant-after-pulling-an-emergency-brake-20240605/.

- ↑ Novick A (1955). "Growth of Bacteria". Annual Review of Microbiology 9: 97–110. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.09.100155.000525. PMID 13259461.

- ↑ "Requirements for Transformation in Bacillus Subtilis". J. Bacteriol. 81 (5): 741–6. 1961. doi:10.1128/JB.81.5.741-746.1961. PMID 16561900.

- ↑ "Studies on the Life and Death of Bacteria: I. The Senescent Phase in Aging Cultures and the Probable Mechanisms Involved". Journal of Bacteriology 38 (3): 249–261. September 1939. doi:10.1128/jb.38.3.249-261.1939. PMID 16560248.

- ↑ "Evolution of microbial diversity during prolonged starvation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 96 (7): 4023–4027. March 1999. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.7.4023. PMID 10097156. Bibcode: 1999PNAS...96.4023F.

- ↑ "Long-term survival during stationary phase: evolution and the GASP phenotype". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 4 (2): 113–120. February 2006. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1340. PMID 16415927.

- ↑ "Psychrophiles and Psychrotrophs". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. 16 April 2007. doi:10.1002/9780470015902.a0000402.pub2. ISBN 9780470016176.

- ↑ "Mesophile" (in en). Biology-Online Dictionary. https://www.biology-online.org/dictionary/Mesophile.

- ↑ "Thermophilic Bacteria". Journal of Bacteriology 4 (4): 301–306. July 1919. doi:10.1128/jb.4.4.301-306.1919. PMID 16558843.

- ↑ "Effect of pH on Growth Rate". http://www.brooklyn.cuny.edu/bc/ahp/CellBio/Growth/MGpH.html.

External links

- An examination of the exponential growth of bacterial populations

- Science aid: Bacterial Growth High school (GCSE, Alevel) resource.

- Microbial Growth, BioMineWiki

- From the Wolfram Demonstrations Project — requires CDF player (free):

- The Final Number of Bacterial Cells

- Simulating Microbial Count Records with an Expanded Fermi Solution Model

- Incipient Growth Processes with Competing Mechanisms

- Modified Logistic Isothermal Microbial Growth Ratio

- Generalized Logistic (Verhulst) Isothermal Microbial Growth

- Microbial Population Growth, Mortality, and Transitions between Them

- Diauxic Growth of Bacteria on Two Substrates

This article includes material from an article posted on 26 April 2003 on Nupedia; written by Nagina Parmar; reviewed and approved by the Biology group; editor, Gaytha Langlois; lead reviewer, Gaytha Langlois; lead copyeditors, Ruth Ifcher. and Jan Hogle.

|

KSF

KSF