Eukaryote

Topic: Biology

From HandWiki - Reading time: 21 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 21 min

| Eukaryota | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota (Chatton, 1925) Whittaker & Margulis, 1978 |

| Supergroups and kingdoms[2] | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

The eukaryotes (/juːˈkærioʊts, -əts/) constitute the domain of Eukarya, organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms are eukaryotes. They constitute a major group of life forms alongside the two groups of prokaryotes: the Bacteria and the Archaea. Eukaryotes represent a small minority of the number of organisms, but given their generally much larger size, their collective global biomass is much larger than that of prokaryotes.

The eukaryotes seemingly emerged in the Archaea, within the Asgard archaea. This implies that there are only two domains of life, Bacteria and Archaea, with eukaryotes incorporated among the Archaea. Eukaryotes first emerged during the Paleoproterozoic, likely as flagellated cells. The leading evolutionary theory is they were created by symbiogenesis between an anaerobic Asgard archaean and an aerobic proteobacterium, which formed the mitochondria. A second episode of symbiogenesis with a cyanobacterium created the plants, with chloroplasts.

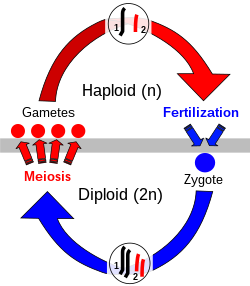

Eukaryotic cells contain membrane-bound organelles such as the nucleus, the endoplasmic reticulum, and the Golgi apparatus. Eukaryotes may be either unicellular or multicellular. In comparison, prokaryotes are typically unicellular. Unicellular eukaryotes are sometimes called protists. Eukaryotes can reproduce both asexually through mitosis and sexually through meiosis and gamete fusion (fertilization).

Diversity

Eukaryotes are organisms that range from microscopic single cells, such as picozoans under 3 micrometres across,[5] to animals like the blue whale, weighing up to 190 tonnes and measuring up to 33.6 metres (110 ft) long,[6] or plants like the coast redwood, up to 120 metres (390 ft) tall.[7] Many eukaryotes are unicellular; the informal grouping called protists includes many of these, with some multicellular forms like the giant kelp up to 200 feet (61 m) long.[8] The multicellular eukaryotes include the animals, plants, and fungi, but again, these groups too contain many unicellular species.[9] Eukaryotic cells are typically much larger than those of prokaryotes—the bacteria and the archaea—having a volume of around 10,000 times greater.[10][11] Eukaryotes represent a small minority of the number of organisms, but, as many of them are much larger, their collective global biomass (468 gigatons) is far larger than that of prokaryotes (77 gigatons), with plants alone accounting for over 81% of the total biomass of Earth.[12]

- Eukaryotes range in size from single cells to organisms weighing many tons

The eukaryotes are a diverse lineage, consisting mainly of microscopic organisms.[13] Multicellularity in some form has evolved independently at least 25 times within the eukaryotes.[14][15] Complex multicellular organisms, not counting the aggregation of amoebae to form slime molds, have evolved within only six eukaryotic lineages: animals, symbiomycotan fungi, brown algae, red algae, green algae, and land plants.[16] Eukaryotes are grouped by genomic similarities, so that groups often lack visible shared characteristics.[13]

Distinguishing features

Nucleus

The defining feature of eukaryotes is that their cells have nuclei. This gives them their name, from the Greek εὖ (eu, "well" or "good") and κάρυον (karyon, "nut" or "kernel", here meaning "nucleus").[17] Eukaryotic cells have a variety of internal membrane-bound structures, called organelles, and a cytoskeleton which defines the cell's organization and shape. The nucleus stores the cell's DNA, which is divided into linear bundles called chromosomes;[18] these are separated into two matching sets by a microtubular spindle during nuclear division, in the distinctively eukaryotic process of mitosis.[19]

Biochemistry

Eukaryotes differ from prokaryotes in multiple ways, with unique biochemical pathways such as sterane synthesis.[20] The eukaryotic signature proteins have no homology to proteins in other domains of life, but appear to be universal among eukaryotes. They include the proteins of the cytoskeleton, the complex transcription machinery, the membrane-sorting systems, the nuclear pore, and some enzymes in the biochemical pathways.[21]

Internal membranes

Eukaryote cells include a variety of membrane-bound structures, together forming the endomembrane system.[22] Simple compartments, called vesicles and vacuoles, can form by budding off other membranes. Many cells ingest food and other materials through a process of endocytosis, where the outer membrane invaginates and then pinches off to form a vesicle.[23] Some cell products can leave in a vesicle through exocytosis.[24]

The nucleus is surrounded by a double membrane known as the nuclear envelope, with nuclear pores that allow material to move in and out.[25] Various tube- and sheet-like extensions of the nuclear membrane form the endoplasmic reticulum, which is involved in protein transport and maturation. It includes the rough endoplasmic reticulum, covered in ribosomes which synthesize proteins; these enter the interior space or lumen. Subsequently, they generally enter vesicles, which bud off from the smooth endoplasmic reticulum.[26] In most eukaryotes, these protein-carrying vesicles are released and further modified in stacks of flattened vesicles (cisternae), the Golgi apparatus.[27]

Vesicles may be specialized; for instance, lysosomes contain digestive enzymes that break down biomolecules in the cytoplasm.[28]

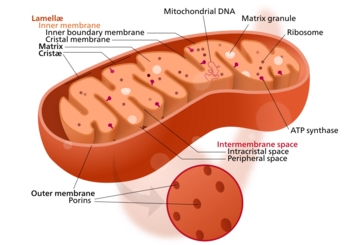

Mitochondria

Mitochondria are organelles in eukaryotic cells. The mitochondrion is commonly called "the powerhouse of the cell",[29] for its function providing energy by oxidising sugars or fats to produce the energy-storing molecule ATP.[30][31] Mitochondria have two surrounding membranes, each a phospholipid bilayer; the inner of which is folded into invaginations called cristae where aerobic respiration takes place.[32]

Mitochondria contain their own DNA, which has close structural similarities to bacterial DNA, from which it originated, and which encodes rRNA and tRNA genes that produce RNA which is closer in structure to bacterial RNA than to eukaryote RNA.[33]

Some eukaryotes, such as the metamonads Giardia and Trichomonas, and the amoebozoan Pelomyxa, appear to lack mitochondria, but all contain mitochondrion-derived organelles, like hydrogenosomes or mitosomes, having lost their mitochondria secondarily.[34] They obtain energy by enzymatic action in the cytoplasm.[35][34]

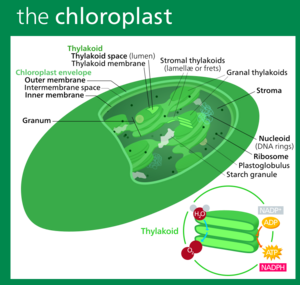

Plastids

Plants and various groups of algae have plastids as well as mitochondria. Plastids, like mitochondria, have their own DNA and are developed from endosymbionts, in this case cyanobacteria. They usually take the form of chloroplasts which, like cyanobacteria, contain chlorophyll and produce organic compounds (such as glucose) through photosynthesis. Others are involved in storing food. Although plastids probably had a single origin, not all plastid-containing groups are closely related. Instead, some eukaryotes have obtained them from others through secondary endosymbiosis or ingestion.[36] The capture and sequestering of photosynthetic cells and chloroplasts, kleptoplasty, occurs in many types of modern eukaryotic organisms.[37][38]

Cytoskeletal structures

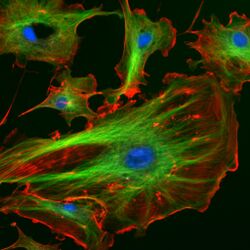

The cytoskeleton provides stiffening structure and points of attachment for motor structures that enable the cell to move, change shape, or transport materials. The motor structures are microfilaments of actin and actin-binding proteins, including α-actinin, fimbrin, and filamin are present in submembranous cortical layers and bundles. Motor proteins of microtubules, dynein and kinesin, and myosin of actin filaments, provide dynamic character of the network.[39][40]

Many eukaryotes have long slender motile cytoplasmic projections, called flagella, or multiple shorter structures called cilia. These organelles are variously involved in movement, feeding, and sensation. They are composed mainly of tubulin, and are entirely distinct from prokaryotic flagella. They are supported by a bundle of microtubules arising from a centriole, characteristically arranged as nine doublets surrounding two singlets. Flagella may have hairs (mastigonemes), as in many Stramenopiles. Their interior is continuous with the cell's cytoplasm.[41][42]

Centrioles are often present, even in cells and groups that do not have flagella, but conifers and flowering plants have neither. They generally occur in groups that give rise to various microtubular roots. These form a primary component of the cytoskeleton, and are often assembled over the course of several cell divisions, with one flagellum retained from the parent and the other derived from it. Centrioles produce the spindle during nuclear division.[43]

Cell wall

The cells of plants, algae, fungi and most chromalveolates, but not animals, are surrounded by a cell wall. This is a layer outside the cell membrane, providing the cell with structural support, protection, and a filtering mechanism. The cell wall also prevents over-expansion when water enters the cell.[44]

The major polysaccharides making up the primary cell wall of land plants are cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin. The cellulose microfibrils are linked together with hemicellulose, embedded in a pectin matrix. The most common hemicellulose in the primary cell wall is xyloglucan.[45]

Sexual reproduction

Eukaryotes have a life cycle that involves sexual reproduction, alternating between a haploid phase, where only one copy of each chromosome is present in each cell, and a diploid phase, with two copies of each chromosome in each cell. The diploid phase is formed by fusion of two haploid gametes, such as eggs and spermatozoa, to form a zygote; this may grow into a body, with its cells dividing by mitosis, and at some stage produce haploid gametes through meiosis, a division that reduces the number of chromosomes and creates genetic variability.[46] There is considerable variation in this pattern. Plants have both haploid and diploid multicellular phases.[47] Eukaryotes have lower metabolic rates and longer generation times than prokaryotes, because they are larger and therefore have a smaller surface area to volume ratio.[48]

The evolution of sexual reproduction may be a primordial characteristic of eukaryotes. Based on a phylogenetic analysis, Dacks and Roger have proposed that facultative sex was present in the group's common ancestor.[49] A core set of genes that function in meiosis is present in both Trichomonas vaginalis and Giardia intestinalis, two organisms previously thought to be asexual.[50][51] Since these two species are descendants of lineages that diverged early from the eukaryotic evolutionary tree, core meiotic genes, and hence sex, were likely present in the common ancestor of eukaryotes.[50][51] Species once thought to be asexual, such as Leishmania parasites, have a sexual cycle.[52] Amoebae, previously regarded as asexual, are anciently sexual; present-day asexual groups likely arose recently.[53]

Evolution

History of classification

In antiquity, the two lineages of animals and plants were recognized by Aristotle and Theophrastus. The lineages were given the taxonomic rank of Kingdom by Linnaeus in the 18th century. Though he included the fungi with plants with some reservations, it was later realized that they are quite distinct and warrant a separate kingdom.[55] The various single-cell eukaryotes were originally placed with plants or animals when they became known. In 1818, the German biologist Georg A. Goldfuss coined the word protozoa to refer to organisms such as ciliates,[56] and this group was expanded until Ernst Haeckel made it a kingdom encompassing all single-celled eukaryotes, the Protista, in 1866.[57][58][59] The eukaryotes thus came to be seen as four kingdoms:

- Kingdom Protista

- Kingdom Plantae

- Kingdom Fungi

- Kingdom Animalia

The protists were at that time thought to be "primitive forms", and thus an evolutionary grade, united by their primitive unicellular nature.[58] Understanding of the oldest branchings in the tree of life only developed substantially with DNA sequencing, leading to a system of domains rather than kingdoms as top level rank being put forward by Carl Woese, Otto Kandler, and Mark Wheelis in 1990, uniting all the eukaryote kingdoms in the domain "Eucarya", stating, however, that "'eukaryotes' will continue to be an acceptable common synonym".[3][60] In 1996, the evolutionary biologist Lynn Margulis proposed to replace Kingdoms and Domains with "inclusive" names to create a "symbiosis-based phylogeny", giving the description "Eukarya (symbiosis-derived nucleated organisms)".[4]

Phylogeny

By 2014, a rough consensus started to emerge from the phylogenomic studies of the previous two decades.[9][61] The majority of eukaryotes can be placed in one of two large clades dubbed Amorphea (similar in composition to the unikont hypothesis) and the Diphoda (formerly bikonts), which includes plants and most algal lineages. A third major grouping, the Excavata, has been abandoned as a formal group as it is paraphyletic.[2] The proposed phylogeny below includes only one group of excavates (Discoba),[62] and incorporates the 2021 proposal that picozoans are close relatives of rhodophytes.[63] The Provora are a group of microbial predators discovered in 2022.[1] The Metamonada are hard to place, being sister possibly to Discoba, possibly to Malawimonada.[13]

| Eukaryotes |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2200 mya? |

Origin of eukaryotes

The origin of the eukaryotic cell, or eukaryogenesis, is a milestone in the evolution of life, since eukaryotes include all complex cells and almost all multicellular organisms. The last eukaryotic common ancestor (LECA) is the hypothetical origin of all living eukaryotes,[65] and was most likely a biological population, not a single individual.[66] The LECA is believed to have been a protist with a nucleus, at least one centriole and flagellum, facultatively aerobic mitochondria, sex (meiosis and syngamy), a dormant cyst with a cell wall of chitin or cellulose, and peroxisomes.[67][68][69]

An endosymbiotic union between a motile anaerobic archaean and an aerobic alphaproteobacterium gave rise to the LECA and all eukaryotes, with mitochondria. A second, much later endosymbiosis with a cyanobacterium gave rise to the ancestor of plants, with chloroplasts.[64]

The presence of eukaryotic biomarkers in archaea points towards an archaeal origin. The genomes of Asgard archaea have plenty of Eukaryotic signature protein genes, which play a crucial role in the development of the cytoskeleton and complex cellular structures characteristic of eukaryotes. In 2022, cryo-electron tomography demonstrated that Asgard archaea have a complex actin-based cytoskeleton, providing the first direct visual evidence of the archaeal ancestry of eukaryotes.[70]

Fossils

The timing of the origin of eukaryotes is hard to determine but the discovery of Qingshania magnificia, the earliest multicelluar eukaryote from North China which lived during 1.635 billion years ago, suggests that the crown group eukaryotes would have originated from the late Paleoproterozoic (Statherian); the earliest unequivocal unicellular eukaryotes which lived during approximately 1.65 billion years ago are also discovered from North China: Tappania plana, Shuiyousphaeridium macroreticulatum, Dictyosphaera macroreticulata, Germinosphaera alveolata, and Valeria lophostriata.[71]

Some acritarchs are known from at least 1.65 billion years ago, and a fossil, Grypania, which may be an alga, is as much as 2.1 billion years old.[72][73] The "problematic"[74] fossil Diskagma has been found in paleosols 2.2 billion years old.[74]

Structures proposed to represent "large colonial organisms" have been found in the black shales of the Palaeoproterozoic such as the Francevillian B Formation, in Gabon, dubbed the "Francevillian biota" which is dated at 2.1 billion years old.[75][76] However, the status of these structures as fossils is contested, with other authors suggesting that they might represent pseudofossils.[77] The oldest fossils than can unambiguously be assigned to eukaryotes are from the Ruyang Group of China, dating to approximately 1.8-1.6 billion years ago.[78] Fossils that are clearly related to modern groups start appearing an estimated 1.2 billion years ago, in the form of red algae, though recent work suggests the existence of fossilized filamentous algae in the Vindhya basin dating back perhaps to 1.6 to 1.7 billion years ago.[79]

The presence of steranes, eukaryotic-specific biomarkers, in Australia n shales previously indicated that eukaryotes were present in these rocks dated at 2.7 billion years old,[20][80] but these Archaean biomarkers have been rebutted as later contaminants.[81] The oldest valid biomarker records are only around 800 million years old.[82] In contrast, a molecular clock analysis suggests the emergence of sterol biosynthesis as early as 2.3 billion years ago.[83] The nature of steranes as eukaryotic biomarkers is further complicated by the production of sterols by some bacteria.[84][85]

Whenever their origins, eukaryotes may not have become ecologically dominant until much later; a massive increase in the zinc composition of marine sediments 800 million years ago has been attributed to the rise of substantial populations of eukaryotes, which preferentially consume and incorporate zinc relative to prokaryotes, approximately a billion years after their origin (at the latest).[86]

See also

- Eukaryote hybrid genome

- List of sequenced eukaryotic genomes

- Parakaryon myojinensis

- Vault (organelle)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Microbial predators form a new supergroup of eukaryotes". Nature 612 (7941): 714–719. December 2022. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05511-5. PMID 36477531. Bibcode: 2022Natur.612..714T.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Revisions to the Classification, Nomenclature, and Diversity of Eukaryotes". The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology 66 (1): 4–119. January 2019. doi:10.1111/jeu.12691. PMID 30257078.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 87 (12): 4576–4579. June 1990. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. PMID 2112744. Bibcode: 1990PNAS...87.4576W.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Margulis, Lynn (6 February 1996). "Archaeal-eubacterial mergers in the origin of Eukarya: phylogenetic classification of life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 93 (3): 1071–1076. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.3.1071. PMID 8577716. Bibcode: 1996PNAS...93.1071M.

- ↑ Seenivasan, Ramkumar; Sausen, Nicole; Medlin, Linda K.; Melkonian, Michael (26 March 2013). "Picomonas judraskeda Gen. Et Sp. Nov.: The First Identified Member of the Picozoa Phylum Nov., a Widespread Group of Picoeukaryotes, Formerly Known as 'Picobiliphytes'". PLOS ONE 8 (3): e59565. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059565. PMID 23555709. Bibcode: 2013PLoSO...859565S.

- ↑ Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. Enfield, Middlesex : Guinness Superlatives. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9. https://archive.org/details/guinnessbookofan00wood.

- ↑ Earle CJ, ed (2017). "Sequoia sempervirens". The Gymnosperm Database. http://www.conifers.org/cu/Sequoia.php.

- ↑ van den Hoek, C.; Mann, D.G.; Jahns, H.M. (1995). Algae An Introduction to Phycology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30419-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=xuUoiFesSHMC.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "The eukaryotic tree of life from a global phylogenomic perspective". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 6 (5): a016147. May 2014. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a016147. PMID 24789819.

- ↑ DeRennaux, B. (2001). "Eukaryotes, Origin of". Encyclopedia of Biodiversity. 2. Elsevier. pp. 329–332. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-384719-5.00174-x. ISBN 9780123847201.

- ↑ "Deep-sea microorganisms and the origin of the eukaryotic cell". Japanese Journal of Protozoology 47 (1,2): 29–48. 2014. http://protistology.jp/journal/jjp47/JJP47YAMAGUCHI.pdf.

- ↑ Bar-On, Yinon M.; Phillips, Rob; Milo, Ron (2018-05-17). "The biomass distribution on Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115 (25): 6506–6511. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711842115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 29784790. Bibcode: 2018PNAS..115.6506B.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Burki, Fabien; Roger, Andrew J.; Brown, Matthew W.; Simpson, Alastair G.B. (2020). "The New Tree of Eukaryotes". Trends in Ecology & Evolution (Elsevier BV) 35 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2019.08.008. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 31606140.

- ↑ Grosberg, RK; Strathmann, RR (2007). "The evolution of multicellularity: A minor major transition?". Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 38: 621–654. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102403.114735. https://grosberglab.faculty.ucdavis.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/453/2017/05/2007-Grosberg-R.-K.-and-R.-R.-Strathmann.pdf.

- ↑ Parfrey, L.W.; Lahr, D.J.G. (2013). "Multicellularity arose several times in the evolution of eukaryotes". BioEssays 35 (4): 339–347. doi:10.1002/bies.201200143. PMID 23315654. http://www.producao.usp.br/bitstream/handle/BDPI/45022/339_ftp.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- ↑ Popper, Zoë A.; Michel, Gurvan; Hervé, Cécile; Domozych, David S.; Willats, William G.T.; Tuohy, Maria G.; Kloareg, Bernard; Stengel, Dagmar B. (2011). "Evolution and diversity of plant cell walls: From algae to flowering plants". Annual Review of Plant Biology 62: 567–590. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103809. PMID 21351878.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "eukaryotic". Online Etymology Dictionary. https://www.etymonline.com/?term=eukaryotic.

- ↑ Bonev, B; Cavalli, G (14 October 2016). "Organization and function of the 3D genome". Nature Reviews Genetics 17 (11): 661–678. doi:10.1038/nrg.2016.112. PMID 27739532.

- ↑ "Mitosis - an overview". https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/mitosis.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Archean molecular fossils and the early rise of eukaryotes". Science 285 (5430): 1033–1036. August 1999. doi:10.1126/science.285.5430.1033. PMID 10446042. Bibcode: 1999Sci...285.1033B.

- ↑ "The origin of the eukaryotic cell: a genomic investigation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (3): 1420–5. February 2002. doi:10.1073/pnas.032658599. PMID 11805300. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99.1420H.

- ↑ "Evolutionary Integration of Chloroplast Metabolism with the Metabolic Networks of the Cells". Functional Genomics and Evolution of Photosynthetic Systems. Springer. 2011. p. 215. ISBN 978-94-007-1533-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=WfzEgaLibuwC&pg=PA215. Retrieved 27 October 2015.

- ↑ Endocytosis. Oxford University Press. 2001. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-19-963851-2.

- ↑ Stalder, Danièle; Gershlick, David C. (November 2020). "Direct trafficking pathways from the Golgi apparatus to the plasma membrane". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 107: 112–125. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.04.001. PMID 32317144.

- ↑ "The nuclear envelope". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2 (3): a000539. March 2010. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a000539. PMID 20300205.

- ↑ "Endoplasmic Reticulum (Rough and Smooth)". British Society for Cell Biology. http://bscb.org/learning-resources/softcell-e-learning/endoplasmic-reticulum-rough-and-smooth/.

- ↑ "Golgi Apparatus". British Society for Cell Biology. http://bscb.org/learning-resources/softcell-e-learning/golgi-apparatus/.

- ↑ "Lysosome". British Society for Cell Biology. http://bscb.org/learning-resources/softcell-e-learning/lysosome/.

- ↑ "Transcriptional profiling of lung cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension". Pulmonary Circulation 10 (1): 131–144. July 1957. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0757-131. PMID 32166015. Bibcode: 1957SciAm.197a.131S.

- ↑ Fundamentals of Biochemistry (2nd ed.). John Wiley and Sons. 2006. pp. 547, 556. ISBN 978-0471214953. https://archive.org/details/fundamentalsofbi00voet_0/page/547.

- ↑ "Re: Are there eukaryotic cells without mitochondria?". madsci.org. 1 May 2006. http://www.madsci.org/posts/archives/2006-05/1146679455.Ev.r.html.

- ↑ Zick, M; Rabl, R; Reichert, AS (January 2009). "Cristae formation-linking ultrastructure and function of mitochondria.". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research 1793 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.06.013. PMID 18620004.

- ↑ "28: The Origins of Life". Molecular Biology of the Gene (Fourth ed.). Menlo Park, California: The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company, Inc.. 1988. p. 1154. ISBN 978-0-8053-9614-0. https://archive.org/details/molecularbiology0004unse/page/1154.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "A Eukaryote without a Mitochondrial Organelle". Current Biology 26 (10): 1274–1284. May 2016. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.03.053. PMID 27185558.

- ↑ "Scientists Shocked To Discover Eukaryote With NO Mitochondria". 13 May 2016. http://www.iflscience.com/plants-and-animals/first-eukaryote-found-lack-mitochondria.

- ↑ "Origin and Evolution of Plastids: Genomic View on the Unification and Diversity of Plastids". The Structure and Function of Plastids. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration. 23. Springer Netherlands. 2006. pp. 75–102. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4061-0_4. ISBN 978-1-4020-4060-3.

- ↑ "Chloroplast DNA content in Dinophysis (Dinophyceae) from different cell cycle stages is consistent with kleptoplasty". Environ. Microbiol. 10 (9): 2411–7. September 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01666.x. PMID 18518896. Bibcode: 2008EnvMi..10.2411M.

- ↑ "Did some red alga-derived plastids evolve via kleptoplastidy? A hypothesis". Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 93 (1): 201–222. February 2018. doi:10.1111/brv.12340. PMID 28544184.

- ↑ Alberts, Bruce; Johnson, Alexander; Lewis, Julian; Raff, Martin; Roberts, Keith; Walter, Peter (2002-01-01). "Molecular Motors". Molecular Biology of the Cell (4th ed.). New York: Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-3218-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK26888/.

- ↑ "Motor Proteins". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 10 (5): a021931. May 2018. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a021931. PMID 29716949.

- ↑ "Prokaryotic motility structures". Microbiology 149 (Pt 2): 295–304. February 2003. doi:10.1099/mic.0.25948-0. PMID 12624192.

- ↑ "Assembly and motility of eukaryotic cilia and flagella. Lessons from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii". Plant Physiology 127 (4): 1500–7. December 2001. doi:10.1104/pp.010807. PMID 11743094.

- ↑ The centrosome and its role in the organization of microtubules. International Review of Cytology. 106. 1987. pp. 227–293. doi:10.1016/S0074-7696(08)61714-3. ISBN 978-0-12-364506-7.

- ↑ The Surprising Archaea: Discovering Another Domain of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2000. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-19-511183-5.

- ↑ "The Structure and Functions of Xyloglucan". Journal of Experimental Botany 40 (1): 1–11. 1989. doi:10.1093/jxb/40.1.1.

- ↑ Hamilton, Matthew B. (2009). Population genetics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4051-3277-0. https://archive.org/details/populationgeneti00hami.

- ↑ Taylor, TN; Kerp, H; Hass, H (2005). "Life history biology of early land plants: Deciphering the gametophyte phase". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 102 (16): 5892–5897. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501985102. PMID 15809414.

- ↑ "Energetics and genetics across the prokaryote-eukaryote divide". Biology Direct 6 (1): 35. June 2011. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-6-35. PMID 21714941.

- ↑ "The first sexual lineage and the relevance of facultative sex". Journal of Molecular Evolution 48 (6): 779–783. June 1999. doi:10.1007/PL00013156. PMID 10229582. Bibcode: 1999JMolE..48..779D.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "A phylogenomic inventory of meiotic genes; evidence for sex in Giardia and an early eukaryotic origin of meiosis". Current Biology 15 (2): 185–191. January 2005. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.01.003. PMID 15668177.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 "An expanded inventory of conserved meiotic genes provides evidence for sex in Trichomonas vaginalis". PLOS ONE 3 (8): e2879. August 2007. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002879. PMID 18663385. Bibcode: 2008PLoSO...3.2879M.

- ↑ "Demonstration of genetic exchange during cyclical development of Leishmania in the sand fly vector". Science 324 (5924): 265–268. April 2009. doi:10.1126/science.1169464. PMID 19359589. Bibcode: 2009Sci...324..265A.

- ↑ "The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating evidence for sex in amoeboid organisms". Proceedings: Biological Sciences 278 (1715): 2081–2090. July 2011. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0289. PMID 21429931.

- ↑ , Wikidata Q123558544

- ↑ "Taxonomic proposals for the classification of marine yeasts and other yeast-like fungi including the smuts". Botanica Marina 23: 361–373. 1980.

- ↑ Goldfuß (1818). "Ueber die Classification der Zoophyten" (in de). Isis, Oder, Encyclopädische Zeitung von Oken 2 (6): 1008–1019. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/47614#page/530/mode/1up. Retrieved 15 March 2019. From p. 1008: "Erste Klasse. Urthiere. Protozoa." (First class. Primordial animals. Protozoa.) [Note: each column of each page of this journal is numbered; there are two columns per page.]

- ↑ "Not plants or animals: a brief history of the origin of Kingdoms Protozoa, Protista and Protoctista". International Microbiology 2 (4): 207–221. 1999. PMID 10943416. http://www.im.microbios.org/08december99/03%20Scamardella.pdf.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Protozoa, Protista, Protoctista: what's in a name?". Journal of the History of Biology 22 (2): 277–305. 1989. doi:10.1007/BF00139515. PMID 11542176. https://zenodo.org/record/1232387. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- ↑ "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms". Science 163 (3863): 150–60. January 1969. doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150. PMID 5762760. Bibcode: 1969Sci...163..150W.

- ↑ Knoll, Andrew H. (1992). "The Early Evolution of Eukaryotes: A Geological Perspective". Science 256 (5057): 622–627. doi:10.1126/science.1585174. PMID 1585174. Bibcode: 1992Sci...256..622K. "Eucarya, or eukaryotes".

- ↑ "Untangling the early diversification of eukaryotes: a phylogenomic study of the evolutionary origins of Centrohelida, Haptophyta and Cryptista". Proceedings: Biological Sciences 283 (1823): 20152802. January 2016. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2802. PMID 26817772.

- ↑ Brown, Matthew W.; Heiss, Aaron A.; Kamikawa, Ryoma; Inagaki, Yuji; Yabuki, Akinori; Tice, Alexander K; Shiratori, Takashi; Ishida, Ken-Ichiro et al. (2018-01-19). "Phylogenomics Places Orphan Protistan Lineages in a Novel Eukaryotic Super-Group". Genome Biology and Evolution 10 (2): 427–433. doi:10.1093/gbe/evy014. PMID 29360967.

- ↑ "Picozoa are archaeplastids without plastid". Nature Communications 12 (1): 6651. 2021. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-26918-0. PMID 34789758. PMC 8599508. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-189959.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "The role of symbiosis in eukaryotic evolution". Origins and Evolution of Life: An astrobiological perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2011. pp. 326–339. ISBN 978-0-521-76131-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=m3oFebknu1cC&pg=PA326. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ↑ "Origin and Early Evolution of the Eukaryotic Cell". Annual Review of Microbiology 75 (1): 631–647. October 2021. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062213. PMID 34343017.

- ↑ "Concepts of the last eukaryotic common ancestor". Nature Ecology & Evolution 3 (3): 338–344. March 2019. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0796-3. PMID 30778187. Bibcode: 2019NatEE...3..338O.

- ↑ "Predatory protists". Current Biology 30 (10): R510–R516. May 2020. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.052. PMID 32428491.

- ↑ "A molecular timescale for eukaryote evolution with implications for the origin of red algal-derived plastids". Nature Communications 12 (1): 1879. March 2021. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22044-z. PMID 33767194. Bibcode: 2021NatCo..12.1879S.

- ↑ Koumandou, V. Lila; Wickstead, Bill; Ginger, Michael L.; van der Giezen, Mark; Dacks, Joel B.; Field, Mark C. (2013). "Molecular paleontology and complexity in the last eukaryotic common ancestor". Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 48 (4): 373–396. doi:10.3109/10409238.2013.821444. PMID 23895660.

- ↑ "Actin cytoskeleton and complex cell architecture in an Asgard archaean". Nature 613 (7943): 332–339. 2023. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05550-y. PMID 36544020. Bibcode: 2023Natur.613..332R.

- ↑ Miao, L.; Yin, Z.; Knoll, A. H.; Qu, Y.; Zhu, M. (2024). "1.63-billion-year-old multicellular eukaryotes from the Chuanlinggou Formation in North China". Science Advances 10 (4): eadk3208. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adk3208.

- ↑ "Megascopic eukaryotic algae from the 2.1-billion-year-old negaunee iron-formation, Michigan". Science 257 (5067): 232–5. July 1992. doi:10.1126/science.1631544. PMID 1631544. Bibcode: 1992Sci...257..232H.

- ↑ "Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 361 (1470): 1023–1038. June 2006. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1843. PMID 16754612.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 "Problematic urn-shaped fossils from a Paleoproterozoic (2.2 Ga) paleosol in South Africa.". Precambrian Research 235: 71–87. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.precamres.2013.05.015. Bibcode: 2013PreR..235...71R.

- ↑ "Large colonial organisms with coordinated growth in oxygenated environments 2.1 Gyr ago". Nature 466 (7302): 100–104. July 2010. doi:10.1038/nature09166. PMID 20596019. Bibcode: 2010Natur.466..100A.

- ↑ El Albani, Abderrazak (2023). "A search for life in Palaeoproterozoic marine sediments using Zn isotopes and geochemistry". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 623: 118169. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118169. Bibcode: 2023E&PSL.61218169E.

- ↑ Ossa Ossa, Frantz; Pons, Marie-Laure; Bekker, Andrey; Hofmann, Axel; Poulton, Simon W. et al. (2023). "Zinc enrichment and isotopic fractionation in a marine habitat of the c. 2.1 Ga Francevillian Group: A signature of zinc utilization by eukaryotes?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 611: 118147. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2023.118147.

- ↑ Fakhraee, Mojtaba; Tarhan, Lidya G.; Reinhard, Christopher T.; Crowe, Sean A.; Lyons, Timothy W.; Planavsky, Noah J. (May 2023). "Earth's surface oxygenation and the rise of eukaryotic life: Relationships to the Lomagundi positive carbon isotope excursion revisited" (in en). Earth-Science Reviews 240: 104398. doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2023.104398. Bibcode: 2023ESRv..24004398F. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0012825223000879.

- ↑ "The controversial "Cambrian" fossils of the Vindhyan are real but more than a billion years older". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106 (19): 7729–7734. May 2009. doi:10.1073/pnas.0812460106. PMID 19416859. Bibcode: 2009PNAS..106.7729B.

- ↑ "Mass extinctions: the microbes strike back". New Scientist: 40–43. 9 February 2008. https://www.newscientist.com/channel/life/mg19726421.900-mass-extinctions-the-microbes-strike-back.html. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ↑ "Reappraisal of hydrocarbon biomarkers in Archean rocks". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 112 (19): 5915–5920. May 2015. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419563112. PMID 25918387. Bibcode: 2015PNAS..112.5915F.

- ↑ "The rise of algae in Cryogenian oceans and the emergence of animals". Nature 548 (7669): 578–581. August 2017. doi:10.1038/nature23457. PMID 28813409. Bibcode: 2017Natur.548..578B.

- ↑ "Paleoproterozoic sterol biosynthesis and the rise of oxygen". Nature 543 (7645): 420–423. March 2017. doi:10.1038/nature21412. PMID 28264195. Bibcode: 2017Natur.543..420G.

- ↑ "Sterol Synthesis in Diverse Bacteria". Frontiers in Microbiology 7: 990. 2016-06-24. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00990. PMID 27446030.

- ↑ "Evolution of bacterial steroid biosynthesis and its impact on eukaryogenesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118 (25): e2101276118. June 2021. doi:10.1073/pnas.2101276118. PMID 34131078. Bibcode: 2021PNAS..11801276H.

- ↑ "Tracking the rise of eukaryotes to ecological dominance with zinc isotopes". Geobiology 16 (4): 341–352. June 2018. doi:10.1111/gbi.12289. PMID 29869832. Bibcode: 2018Gbio...16..341I.

External links

Wikidata ☰ Q19088 entry

|

KSF

KSF