Glycation

Topic: Biology

From HandWiki - Reading time: 3 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 3 min

Glycation (sometimes called non-enzymatic glycosylation) is the covalent attachment of a sugar to a protein or lipid. Typical sugars that participate in glycation are glucose, fructose, or their derivatives. Glycation is a biomarker for diabetes and is implicated in some diseases and in aging.[1][2][3] Glycation end products are believed to play a causative role in the vascular complications of diabetes mellitus.[4] In contrast with glycation, glycosylation is the enzyme-mediated ATP-dependent attachment of sugars to protein or lipid. Glycosylation occurs at defined sites on the target molecule. It is a common form of post-translational modification of proteins and is required for the functioning of the mature protein.

Biochemistry

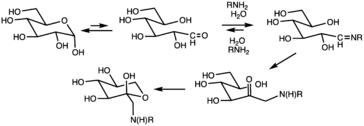

Glycations occur mainly in the bloodstream to a small proportion of the absorbed simple sugars: glucose, fructose, and galactose. It appears that fructose has approximately ten times the glycation activity of glucose, the primary body fuel.[7] Glycation can occur through Amadori reactions, Schiff base reactions, and Maillard reactions; which lead to advanced glycation end products (AGEs).

Biomedical implications

Red blood cells have a consistent lifespan of 120 days and are accessible for measurement of glycated hemoglobin. Measurement of HbA1c—the predominant form of glycated hemoglobin—enables medium-term blood sugar control to be monitored in diabetes.

Some glycation product are implicated in many age-related chronic diseases. Glycation cardiovascular diseases (the endothelium, fibrinogen, and collagen are damaged), Alzheimer's disease (amyloid proteins are side-products of the reactions progressing to AGEs),[8][9]

Long-lived cells (such as nerves and different types of brain cell), long-lasting proteins (such as crystallins of the lens and cornea), and DNA can sustain substantial glycation over time. Damage by glycation results in stiffening of the collagen in the blood vessel walls, leading to high blood pressure, especially in diabetes.[10] Glycations also cause weakening of the collagen in the blood vessel walls,[citation needed] which may lead to micro- or macro-aneurysm; this may cause strokes if in the brain.

See also

- Advanced glycation end-product

- Alagebrium

- Fructose

- Galactose

- Glucose

- Glycosylation

- List of aging processes

Additional reading

- "Failure of common glycation assays to detect glycation by fructose". Clin. Chem. 38 (7): 1301–3. July 1992. doi:10.1093/clinchem/38.7.1301. PMID 1623595.

- Vlassara H (June 2005). "Advanced glycation in health and disease: role of the modern environment". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1043 (1): 452–60. doi:10.1196/annals.1333.051. PMID 16037266. Bibcode: 2005NYASA1043..452V.

References

- ↑ Glenn, J.; Stitt, A. (2009). "The role of advanced glycation end products in retinal ageing and disease". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 1790 (10): 1109–1116. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.04.016. PMID 19409449.

- ↑ Semba, R. D.; Ferrucci, L.; Sun, K.; Beck, J.; Dalal, M.; Varadhan, R.; Walston, J.; Guralnik, J. M. et al. (2009). "Advanced glycation end products and their circulating receptors predict cardiovascular disease mortality in older community-dwelling women". Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 21 (2): 182–190. doi:10.1007/BF03325227. PMID 19448391.

- ↑ Semba, R.; Najjar, S.; Sun, K.; Lakatta, E.; Ferrucci, L. (2009). "Serum carboxymethyl-lysine, an advanced glycation end product, is associated with increased aortic pulse wave velocity in adults". American Journal of Hypertension 22 (1): 74–79. doi:10.1038/ajh.2008.320. PMID 19023277.

- ↑ Yan, S. F.; D'Agati, V.; Schmidt, A. M.; Ramasamy, R. (2007). "Receptor for Advanced Glycation Endproducts (RAGE): a formidable force in the pathogenesis of the cardiovascular complications of diabetes & aging". Current Molecular Medicine 7 (8): 699–710. doi:10.2174/156652407783220732. PMID 18331228.

- ↑ Yaylayan, Varoujan A.; Huyghues-Despointes, Alexis (1994). "Chemistry of Amadori Rearrangement Products: Analysis, Synthesis, Kinetics, Reactions, and Spectroscopic Properties". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 34 (4): 321–69. doi:10.1080/10408399409527667. PMID 7945894.

- ↑ Bellier, Justine; Nokin, Marie-Julie; Lardé, Eva; Karoyan, Philippe; Peulen, Olivier; Castronovo, Vincent; Bellahcène, Akeila (2019). "Methylglyoxal, a Potent Inducer of AGEs, Connects between Diabetes and Cancer". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 148: 200–211. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2019.01.002. PMID 30664892.

- ↑ "Role of fructose in glycation and cross-linking of proteins". Biochemistry 27 (6): 1901–7. March 1988. doi:10.1021/bi00406a016. PMID 3132203.

- ↑ Münch, Gerald (27 February 1997). "Influence of advanced glycation end-products and AGE-inhibitors on nucleation-dependent polymerization of β-amyloid peptide". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 1360 (1): 17–29. doi:10.1016/S0925-4439(96)00062-2. PMID 9061036.

- ↑ Munch, G; Deuther-Conrad W; Gasic-Milenkovic J. (2002). "Glycoxidative stress creates a vicious cycle of neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease--a target for neuroprotective treatment strategies?". J Neural Transm Suppl 62 (62): 303–307. doi:10.1007/978-3-7091-6139-5_28. PMID 12456073.

- ↑ Soldatos, G.; Cooper ME (Dec 2006). "Advanced glycation end products and vascular structure and function". Curr Hypertens Rep 8 (6): 472–478. doi:10.1007/s11906-006-0025-8. PMID 17087858.

KSF

KSF