Nucleomodulin

Topic: Biology

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 5 min

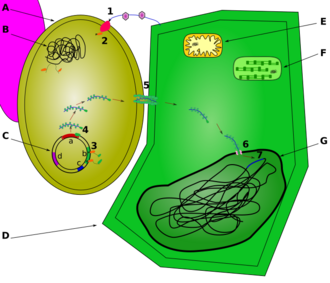

Nucleomodulins are a family of bacterial proteins that enter the nucleus of eukaryotic cells.[1]

This term comes from the contraction between "nucleus" and "modulins", which are microbial molecules that modulate the behaviour of eukaryotic cells. Nucleomodulins are produced by pathogenic or symbiotic bacteria. They act on various processes in the nucleus: remodelling of the chromatin structure,[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][excessive citations] transcription,[13][14] splicing of pre-messenger RNA,[15][16] cell division.[17]

The identification of nucleomodulins in several species of bacterial pathogens of humans, animals and plants has led to the emergence of the concept that direct control of the nucleus is one of the most sophisticated strategies used by microbes to bypass host defences. Nucleomodulins can be directly secreted into the intracellular medium after entry of the bacteria into the cell, like Listeria monocytogenes, or they can be injected from the extracellular medium or intracellular organelles using a type III or IV bacterial secretion system, also known as a "molecular syringe".[citation needed]

More recently, it has been shown that some of them, such as YopM from Yersinia pestis and IpaH9.8 from Shigella flexneri, can autonomously penetrate eukaryotic cells thanks to a membrane transduction domain.[18]

The diversity of molecular mechanisms triggered by nucleomodulins [1][19] is a source of inspiration for new biotechnologies. They are true nano-machines capable of hijacking a multitude of nuclear processes. In research, nucleomodulins are the subject of in-depth studies that have led to the discovery of new human nuclear regulators, such as the epigenetic regulator BAHD1.[8]

Examples

Agrobacterium tumefaciens, responsible for crown gall disease, produces an arsenal of Vir proteins, including VirD2 and VirE2, enabling the precise integration of a piece of its DNA, called T-DNA, into that of the host plant [20]

Listeria monocytogenes, responsible for listeriosis, can modulate the expression of immunity genes. One of the mechanisms at play involves the bacterial protein LntA, which inhibits the function of the epigenetic regulator BAHD1. The action of this nucleomodulin is associated with chromatin decompaction and activation of an interferon response genes.[8][21]

Shigella flexneri, responsible for shigellosis, secretes the IpaH9.8 protein targeting a mRNA splicing protein that disrupts the production of protein isoforms and the inflammatory response in humans.[16]

Legionella pneumophila, responsible for legionellosis, secretes an enzyme with histone methyltransferase activity capable of methylating histones at different chromosome loci [22] or at the level of ribosomal DNA (rDNA) in the nucleolus.[23]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Bierne, Hélène; Cossart, Pascale (May 2012). "When bacteria target the nucleus: the emerging family of nucleomodulins". Cellular Microbiology 14 (5): 622–33. doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01758.x. ISSN 1462-5822. PMID 22289128.

- ↑ Skrzypek, E.; Cowan, C.; Straley, S. C. (December 1998). "Targeting of the Yersinia pestis YopM protein into HeLa cells and intracellular trafficking to the nucleus". Molecular Microbiology 30 (5): 1051–65. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01135.x. ISSN 0950-382X. PMID 9988481.

- ↑ Li, Hongtao; Xu, Hao; Zhou, Yan; Zhang, Jie (2007-02-16). "The phosphothreonine lyase activity of a bacterial type III effector family". Science 315 (5814): 1000–3. doi:10.1126/science.1138960. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 17303758. Bibcode: 2007Sci...315.1000L.

- ↑ Arbibe, Laurence; Kim, Dong Wook; Batsche, Eric; Pedron, Thierry (January 2007). "An injected bacterial effector targets chromatin access for transcription factor NF-kappaB to alter transcription of host genes involved in immune responses". Nature Immunology 8 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1038/ni1423. ISSN 1529-2908. PMID 17159983.

- ↑ Pennini, Meghan E.; Perrinet, Stéphanie; Dautry-Varsat, Alice; Subtil, Agathe (2010-07-15). "Histone methylation by NUE, a novel nuclear effector of the intracellular pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis". PLOS Pathogens 6 (7): e1000995. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000995. ISSN 1553-7374. PMID 20657819.

- ↑ Rolando, Monica; Sanulli, Serena; Rusniok, Christophe; Gomez-Valero, Laura (April 2013). "Legionella pneumophila Effector RomA Uniquely Modifies Host Chromatin to Repress Gene Expression and Promote Intracellular Bacterial Replication" (in en). Cell Host & Microbe 13 (4): 395–405. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.004. PMID 23601102.

- ↑ Li, Ting; Lu, Qiuhe; Wang, Guolun; Xu, Hao (August 2013). "SET‐domain bacterial effectors target heterochromatin protein 1 to activate host rDNA transcription" (in en). EMBO Reports 14 (8): 733–40. doi:10.1038/embor.2013.86. ISSN 1469-221X. PMID 23797873.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Lebreton, Alice; Lakisic, Goran; Job, Viviana; Fritsch, Lauriane (2011-03-11). "A bacterial protein targets the BAHD1 chromatin complex to stimulate type III interferon response". Science 331 (6022): 1319–21. doi:10.1126/science.1200120. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 21252314. Bibcode: 2011Sci...331.1319L. https://hal-cea.archives-ouvertes.fr/cea-00819299/file/Science_2011_post-print.pdf.

- ↑ Rennoll-Bankert, Kristen E.; Garcia-Garcia, Jose C.; Sinclair, Sara H.; Dumler, J. Stephen (November 2015). "Chromatin-bound bacterial effector ankyrin A recruits histone deacetylase 1 and modifies host gene expression: AnkA recruits HDAC1 to modify CYBB expression" (in en). Cellular Microbiology 17 (11): 1640–52. doi:10.1111/cmi.12461. PMID 25996657.

- ↑ Farris, Tierra R.; Dunphy, Paige S.; Zhu, Bing; Kibler, Clayton E. (November 2016). "Ehrlichia chaffeensis TRP32 Is a Nucleomodulin That Directly Regulates Expression of Host Genes Governing Differentiation and Proliferation" (in en). Infection and Immunity 84 (11): 3182–3194. doi:10.1128/IAI.00657-16. ISSN 0019-9567. PMID 27572329.

- ↑ Mitra, Shubhajit; Dunphy, Paige S.; Das, Seema; Zhu, Bing (2018-01-22). "Ehrlichia chaffeensis TRP120 Effector Targets and Recruits Host Polycomb Group Proteins for Degradation To Promote Intracellular Infection" (in en). Infection and Immunity 86 (4): e00845–17, /iai/86/4/e00845–17.atom. doi:10.1128/IAI.00845-17. ISSN 0019-9567. PMID 29358333.

- ↑ Yaseen, Imtiyaz; Kaur, Prabhjot; Nandicoori, Vinay Kumar; Khosla, Sanjeev (December 2015). "Mycobacteria modulate host epigenetic machinery by Rv1988 methylation of a non-tail arginine of histone H3" (in en). Nature Communications 6 (1): 8922. doi:10.1038/ncomms9922. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 26568365. Bibcode: 2015NatCo...6.8922Y.

- ↑ Kay, Sabine; Hahn, Simone; Marois, Eric; Hause, Gerd (2007-10-26). "A Bacterial Effector Acts as a Plant Transcription Factor and Induces a Cell Size Regulator" (in en). Science 318 (5850): 648–651. doi:10.1126/science.1144956. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17962565. Bibcode: 2007Sci...318..648K.

- ↑ Römer, Patrick; Hahn, Simone; Jordan, Tina; Strauß, Tina (2007-10-26). "Plant Pathogen Recognition Mediated by Promoter Activation of the Pepper Bs3 Resistance Gene" (in en). Science 318 (5850): 645–8. doi:10.1126/science.1144958. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17962564. Bibcode: 2007Sci...318..645R.

- ↑ Toyotome, Takahito; Suzuki, Toshihiko; Kuwae, Asaomi; Nonaka, Takashi (2001-08-24). "Shigella Protein IpaH 9.8 Is Secreted from Bacteria within Mammalian Cells and Transported to the Nucleus" (in en). Journal of Biological Chemistry 276 (34): 32071–32079. doi:10.1074/jbc.M101882200. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 11418613.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Okuda, Jun; Toyotome, Takahito; Kataoka, Naoyuki; Ohno, Mutsuhito (July 2005). "Shigella effector IpaH9.8 binds to a splicing factor U2AF35 to modulate host immune responses" (in en). Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 333 (2): 531–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.145. PMID 15950937.

- ↑ Taieb, Frédéric; Nougayrède, Jean-Philippe; Oswald, Eric (2011-03-29). "Cycle Inhibiting Factors (Cifs): Cyclomodulins That Usurp the Ubiquitin-Dependent Degradation Pathway of Host Cells" (in en). Toxins 3 (4): 356–68. doi:10.3390/toxins3040356. ISSN 2072-6651. PMID 22069713.

- ↑ Norkowski, Stefanie; Körner, Britta; Greune, Lilo; Stolle, Anne-Sophie; Lubos, Marie-Luise; Hardwidge, Philip R.; Schmidt, M. Alexander; Rüter, Christian (2018-06-01). "Bacterial LPX motif-harboring virulence factors constitute a species-spanning family of cell-penetrating effectors" (in en). Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 75 (12): 2273–2289. doi:10.1007/s00018-017-2733-4. ISSN 1420-9071. PMID 29285573.

- ↑ Bierne, Hélène (2017), "Cross Talk Between Bacteria and the Host Epigenetic Machinery", in Doerfler, Walter; Casadesús, Josep (in en), Epigenetics of Infectious Diseases, Epigenetics and Human Health, Springer International Publishing, pp. 113–158, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-55021-3_6, ISBN 978-3-319-55021-3

- ↑ Pelczar, Pawel; Kalck, Véronique; Gomez, Divina; Hohn, Barbara (June 2004). "Agrobacterium proteins VirD2 and VirE2 mediate precise integration of synthetic T-DNA complexes in mammalian cells". EMBO Reports 5 (6): 632–7. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400165. ISSN 1469-221X. PMID 15153934.

- ↑ Lebreton, Alice; Job, Viviana; Ragon, Marie; Le Monnier, Alban (2014-01-21). "Structural basis for the inhibition of the chromatin repressor BAHD1 by the bacterial nucleomodulin LntA". mBio 5 (1): e00775-13. doi:10.1128/mBio.00775-13. ISSN 2150-7511. PMID 24449750.

- ↑ Rolando, Monica et al. (April 2013). "Legionella pneumophila Effector RomA Uniquely Modifies Host Chromatin to Repress Gene Expression and Promote Intracellular Bacterial Replication" (in en). Cell Host & Microbe 13 (4): 395–405. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.004. PMID 23601102.

- ↑ Li, Ting et al. (August 2013). "SET‐domain bacterial effectors target heterochromatin protein 1 to activate host rDNA transcription" (in en). EMBO Reports 14 (8): 733–740. doi:10.1038/embor.2013.86. ISSN 1469-221X. PMID 23797873.

|

KSF

KSF