Outline of lichens

Topic: Biology

From HandWiki - Reading time: 22 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 22 min

Template:Featured list is only for Wikipedia:Featured lists.

The following outline provides an overview of and topical guide to lichens.

Lichen – composite organism made up of multiple species – a fungal partner, one or more photosynthetic partners, which can be either green algae or cyanobacteria, and, in at least 52 genera of lichens, a yeast.[1] In American English, "lichen" is pronounced the same as the verb "liken" (/ˈlaɪkən/). In British English, both this pronunciation and one rhyming with "kitchen" (/ˈlɪtʃən/) are used.[2]

What type of thing is a lichen?

A lichen can be described as all of the following:

- Life form – an entity that is alive.

- Composite organism – a symbiotic life form composed of multiple partners from different biological domains, families and kingdoms, and into different phyla, classes and divisions within those domains and kingdoms. In the case of lichens, a fungal partner (the mycobiont) combines with one or more photosynthetic partner(s) (the photobiont) as well as (in some cases) a yeast.

- Eukaryote (domain) – organisms with a cell nucleus within a nuclear envelope; both the mycobiont and any algal partners fall into this domain.[3]

-

- Ascomycota (phylum) and/or Basidiomycota (phylum)[4]

- For the biological classes and families these fungi belong to, see below.

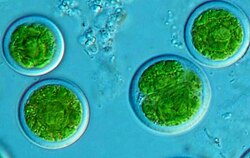

- Chlorophyta (division) – if the photobiont is a green alga, it falls into this taxonomic division.[5]

- Trebouxiophyceae (class)

- Trebouxiaceae (family)[6]

- Ulvophyceae (class)

- Trentepohliaceae (family)[6]

- Prokaryote (domain) – organisms without a cell nucleus; any cyanobacterial partner falls into this domain.[3]

-

- Cyanobacteria (phylum)[7]

Nature of lichens

(a) The cortex is the outer layer of tightly woven fungal filaments (hyphae)

(b) This photobiont layer has photosynthesizing green algae

(c) Loosely packed hyphae in the medulla

(d) A tightly woven lower cortex

(e) Anchoring hyphae called rhizines, where the fungus attaches to the substrate

Morphology

- Lichen anatomy and physiology

- Apoplast – the symbiotic interface zone between the mycobiont and photobiont, outside the cell membranes or walls of both.[8]

- Haustorium (pl. haustoria) – a root-like structure which allows the fungal partner to extract nutrients from its photosynthetic partner(s).[9]

- Lichen morphology – a lichen's external appearance and structures are very different than those of its individual partners.[10]

-

- Cephalodium (pl. cephalodia) – a gall-like structure that contains cyanobacteria[15]

- Hypha (pl. hyphae) – a long, branching, thread-like structure composed of one or more fungal cells, which typically makes up a large part of lichens; hyphae are densely compacted in the cortex and more loosely interwoven in the medulla.[16]

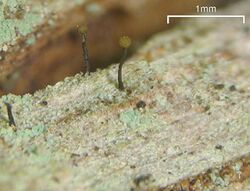

- Pycnidium (pl. pycnidia) – a flask-shaped, asexual fruiting body possessed by some lichens.[17]

- Rhizine – a root-like structure that anchors a lichen to the substrate on which it grows.[19]

- Soralium (pl. soralia) – a localized region or structure, typically a crack or pore, containing soredium.[20]

- Thallus (pl. thalli) – the vegetative body of a lichen, made up of both mycobiont and photobiont components.[21]

- Cortex – the lichen's outer layer(s), made up of tightly woven fungal filaments.[22]

- Isidium (pl. isidia) – outgrowths of the thallus which contain photobiont cells and provide means of vegetative reproduction for some lichens.[23]

- Medulla – a loose layer of interwoven fungal hyphae within the thallus.[24]

- Podetium (pl. podetia) – an upright secondary thallus, which supports the fruiting bodies of Cladonia species.[25]

Ecology

- Symbiosis in lichens – the relationship between the lichen partners can be complicated; while generally mutualistic, sometimes it is not. Recent research also shows other partners, including bacteria and "accessory" fungi, may be involved.[27]

- Asexual reproduction in lichens – many lichens reproduce asexually, using one or more of various methods which allow the dispersal of bundles of both fungal hyphae and photobionts.[28]

- Sexual reproduction in lichens – most lichens reproduce sexually using ascospores, which means they have to acquire their photobiont partners somehow after germinating.[29]

- Lichens and nitrogen cycling – some lichens (in particular those with cyanobacteria as a photobiont) can fix nitrogen.[26]

- Lichen biogeography – the study of the current distribution of extant lichens and the reasons for those distributions.[30]

- Lichen resynthesis – lichens can be artificially "recreated" by combining partners in a lab.[31]

- Lichens and pedogenesis – lichens contribute to the formation of soil by breaking down rock.[32]

- Biological soil crust – lichens are among the common dominant biota in biocrusts, one of the world's largest environmental community types in terms of area covered.[33]

- Photosynthesis in lichens

Types of lichens

Lichen lists

Lichen taxonomical classifications

Lichen systematics – Although they are composite organisms, lichens have traditionally been classified on the basis of their fungal partner. These span eight different biological classes, 39 orders, 117 families, and around 1,000 genera.[34][35]

- Ascolichen – a lichen whose fungal partner is a member of the Ascomycota, one of the two main fungal divisions.[36]

- Basidiolichen – a lichen whose fungal partner is a member of the Basidiomycota, the other of the two main fungal divisions; these are far fewer in occurrence than ascolichens.[37]

Classes

Lichens fall into eight fungal classes and several subclasses:[38]

Orders

They are split across nearly 40 orders. Those which cannot be assigned to a particular order are assigned instead to "incertae sedis" within the appropriate class. These orders were listed in Lücking, Hodkinson and Leavitt's 2016 treatise on the classification of lichenized fungi, except where otherwise noted,[38] with orders updated in 2021.[34]

- Acarosporales

- Agaricales

- Arthoniales

- Atheliales

- Baeomycetales

- Caliciales

- Candelariales

- Cantharellales

- Capnodiales

- Chaetothyriales

- Collemopsidiales

- Coniocybales

- Corticiales

- Eremithallales

- Lecanorales

- Lecideales

- Lepidostromatales

- Leprocaulales

- Lichinales

- Monoblastiales

- Odontotrematales

- Ostropales

- Peltigerales

- Pertusariales

- Phaeomoniellales

- Pleosporales

- Pyrenulales

- Rhizocarpales

- Sarrameanales

- Schaereriales[39][40]

- Strigulales

- Teloschistales

- Thelenellales[39][40]

- Thelocarpales

- Trypetheliales

- Umbilicariales

- Verrucariales

- Vezdaeales

- Xylariales

Families

They fall into 117 families. Those which cannot be assigned to a particular family are assigned instead to "incertae sedis" within the appropriate order. These were listed in Lücking, Hodkinson and Leavitt's 2016 treatise on the classification of lichenized fungi, except where otherwise noted;[35] families were updated in 2021.[34]

- Acarosporaceae

- Agyriaceae

- Andreiomycetaceae

- Aphanopsidaceae

- Arctomiaceae

- Arthoniaceae

- Arthrorhaphidaceae

- Atheliaceae

- Baeomycetaceae

- Biatorellaceae

- Brigantiaeaceae

- Caliciaceae

- Cameroniaceae

- Candelariaceae

- Carbonicolaceae

- Catillariaceae

- Celotheliaceae

- Chrysotrichaceae

- Cladoniaceae

- Clavulinaceae

- Coccocarpiaceae

- Coccotremataceae

- Coenogoniaceae

- Collemataceae

- Coniocybaceae

- Corticiaceae

- Cystocoleaceae

- Dacampiaceae

- Dactylosporaceae

- Elixiaceae

- Fuscideaceae[41]

- Gloeoheppiaceae

- Gomphillaceae

- Graphidaceae

- Gyalectaceae

- Gypsoplacaceae

- Haematommataceae

- Harpidiaceae[42]

- Helocarpaceae

- Hygrophoraceae

- Hymeneliaceae

- Icmadophilaceae

- Koerberiaceae

- Lecanographaceae

- Lecanoraceae

- Lecideaceae

- Lepidostromataceae

- Leprocaulaceae

- Letrouitiaceae

- Lichinaceae

- Lopadiaceae

- Lyrommataceae

- Malmideaceae

- Massalongiaceae

- Megalariaceae

- Megalosporaceae

- Megasporaceae

- Melaspileaceae

- Microtheliopsidaceae

- Monoblastiaceae

- Mycoporaceae

- Nephromataceae

- Ochrolechiaceae

- Opegraphaceae

- Ophioparmaceae

- Pachyascaceae

- Pannariaceae

- Parmeliaceae

- Peltigeraceae

- Peltulaceae

- Pertusariaceae

- Phaneromycetaceae[41][43]

- Phlyctidaceae

- Physciaceae

- Pilocarpaceae

- Placynthiaceae

- Protothelenellaceae

- Psilolechiaceae

- Psoraceae

- Pycnoraceae

- Pyrenotrichaceae

- Pyrenulaceae

- Ramalinaceae

- Ramboldiaceae

- Redonographaceae[41]

- Requienellaceae

- Rhizocarpaceae

- Roccellaceae

- Roccellographaceae

- Ropalosporaceae

- Sagiolechiaceae

- Sarrameanaceae

- Schaereriaceae

- Scoliciosporaceae

- Sphaerophoraceae

- Sporastatiaceae

- Stereocaulaceae

- Stictidaceae

- Strangosporaceae

- Strigulaceae

- Teloschistaceae

- Tenuitholiascaceae[44][45]

- Tephromelataceae

- Thelenellaceae

- Thelocarpaceae

- Thrombiaceae

- Trapeliaceae

- Trichosphaeriaceae[42]

- Trichotheliaceae[41]

- Trypetheliaceae

- Umbilicariaceae

- Vahliellaceae

- Varicellariaceae

- Verrucariaceae

- Vezdaeaceae

- Xanthopyreniaceae

- Xylographaceae

Genera

Extant lichens are found in more than 1000 genera. These were listed in Lücking, Hodkinson and Leavitt's 2016 treatise on the classification of lichenized fungi, except where otherwise noted.[35]

- Absconditella

- Acantholichen

- Acanthothecis

- Acanthotrema

- Acarospora

- Acarosporina

- Aciculopsora

- Acolium

- Acrocordia

- Acroscyphus

- Actinoplaca

- Adelolecia

- Aderkomyces

- Aggregatorygma

- Agonimia

- Ahtiana

- Ainoa

- Albemarlea[46]

- Alectoria

- Allantoparmelia

- Allocalicium

- Allocetraria

- Allographa[47]

- Allophoron[42]

- Alyxoria

- Amandinea

- Amazonomyces

- Amazonotrema

- Ameliella

- Amphorothecium

- Ampliotrema

- Amundsenia

- Amygdalaria

- Amylora

- Anamylopsora

- Anaptychia

- Ancistrosporella

- Andina[48]

- Andreiomyces

- Anema

- Angiactis

- Anisomeridium

- Anomalographis

- Anomomorpha

- Antennulariella

- Anthracocarpon

- Anthracothecium

- Anzia

- Anzina

- Apatoplaca

- Aphanopsis

- Aplanocalenia

- Aptrootia

- Aquacidia[49]

- Architrypethelium

- Arctocetraria

- Arctomia

- Arctoparmelia

- Argopsis

- Aridoplaca[50]

- Arrhenia

- Arthonia (list)

- Arthopyrenia

- Arthotheliopsis

- Arthothelium

- Arthrorhaphis

- Arthrosporum

- Asahinea

- Aspicilia

- Aspiciliopsis

- Aspidothelium

- Aspilidea

- Asteristion

- Asteroporum

- Asterothyrium

- Astrochapsa

- Astrothelium

- Athallia

- Athelopsis

- Atla

- Atrophysma[51]

- Aulaxina

- Auriculora

- Australiaena

- Australidea[52]

- Austrella

- Austrographa

- Austrolecia

- Austromelanelixia[53][54]

- Austroparmelina

- Austropeltum

- Austroplaca

- Austroroccella

- Austrotrema

- Awasthiella

- Bacidia

- Bacidina

- Bacidiopsora

- Bactrospora

- Baculifera

- Badimia

- Badimiella

- Baeomyces

- Baflavia

- Bagliettoa

- Bahianora

- Baidera[55]

- Bapalmuia

- Bartlettiella

- Barubria

- Bathelium

- Bellemerea

- Biatora

- Biatorella

- Biatoridium

- Bibbya[56]

- Bilimbia

- Blastenia

- Blastodesmia

- Blennothallia

- Bogoriella

- Boreoplaca

- Borinquenotrema

- Botryolepraria

- Bouvetiella

- Brasilicia

- Brianaria

- Brigantiaea

- Brodoa

- Brownliella

- Bryobilimbia

- Bryocaulon

- Bryodina

- Bryogomphus

- Bryonora

- Bryoplaca

- Bryoria

- Bryostigma

- Buellia (list)

- Buelliastrum

- Bulbothrix

- Bunodophoron

- Burrowsia[57]

- Byssolecania

- Byssoloma

- Byssotrema

- Caeruleum

- Calathaspis

- Calenia

- Caleniopsis

- Calicium

- Callome

- Calogaya

- Calopadia

- Calopadiopsis

- Caloplaca (list)

- Calotrichopsis

- Calvitimela

- Calycidium

- Cameronia

- Candelaria

- Candelariella

- Candelina

- Canoparmelia

- Caprettia

- Carassea

- Carbacanthographis

- Carbonicola

- Catapyrenium

- Catarrhospora

- Catarraphia

- Catenarina

- Catillaria

- Catillochroma

- Catinaria

- Catolechia

- Cecidonia

- Celothelium

- Cenozosia

- Cephalophysis

- Cerothallia

- Cetradonia

- Cetraria

- Cetrariella

- Cetrelia

- Cetreliopsis

- Chaenotheca

- Chapsa

- Charcotiana

- Cheiromycina

- Chiodecton

- Chirleja

- Chrismofulvea

- Chromatochlamys

- Chroodiscus

- Chrysothrix

- Cinnabaria[58]

- Ciposia

- Circinaria

- Cladia

- Cladidium

- Claurouxia

- Cladonia (list)

- Clandestinotrema

- Clathroporina

- Clauzadea

- Clauzadeana

- Clauzadella

- Clavascidium

- Cliostomum

- Clypeopyrenis

- Coccocarpia

- Coccotrema

- Coelopogon

- Coenogonium

- Collema

- Collemopsidium

- Combea

- Compositrema

- Compsocladium

- Coniangium

- Coniarthonia

- Coniocarpon

- Conotremopsis

- Constrictolumina

- Coppinsia

- Coppinsidea[59]

- Cora

- Corella

- Coronoplectrum

- Cornicularia

- Corticorygma

- Corynecystis

- Coscinocladium

- Cratiria

- Creographa

- Crespoa

- Cresponea

- Cresporhaphis[42]

- Crocellina

- Crocodia

- Crocynia

- Cruentotrema

- Crustospathula

- Crutarndina

- Cryptodictyon

- Cryptodiscus

- Crypthonia

- Cryptophaea

- Cryptothecia

- Cryptothele

- Culbersonia

- Cyanoporina

- Cyphelium

- Cyphellostereum

- Cyphobasidium

- Cystocoleus

- Dacampia

- Dactylina

- Davidgallowaya

- Degelia

- Dendriscosticta

- Dendrographa

- Dermatiscum

- Dermatocarpon

- Dermiscellum

- Diaphorographis

- Dibaeis

- Dichosporidium

- Dictyocatenulata

- Dictyographa

- Dictyomeridium

- Dictyonema

- Digitothyrea

- Dijigiella[60][61]

- Dimelaena

- Dimidiographa

- Diorygma

- Diploicia

- Diploschistella

- Diploschistes

- Diplotomma

- Dirinaria

- Dirina

- Dirinastrum

- Diromma

- Distopyrenis

- Distothelia

- Dolichocarpus

- Dolichousnea[62][54]

- Ducatina[63][64]

- Dufourea

- Dyplolabia

- Echidnocymbium

- Echinoplaca

- Edrudia

- Edwardiella

- Eiglera

- Eilifdahlia

- Elixia

- Elixjohnia[65][61]

- Emmanuelia[66]

- Emodomelanelia

- Encephalographa

- Enchylium

- Endocarpon

- Endocena

- Endohyalina

- Enterodictyon

- Enterographa

- Epilichen

- Enigmotrema

- Eopyrenula

- Ephebe

- Eremastrella

- Eremithallus

- Eremothecella

- Erinacellus

- Erioderma

- Ertzia

- Erythrodecton

- Eschatogonia

- Esslingeriana

- Eugeniella

- Eumitria[62][54]

- Euopsis

- Evernia

- Everniopsis

- Farnoldia

- Fauriea

- Feigeana

- Felipes

- Fellhanera

- Fellhaneropsis

- Ferraroa

- Fibrillithecis

- Filsoniana

- Finkia

- Fissurina

- Flabelloporina[67]

- Flakea

- Flavobathelium

- Flavocetraria

- Flavoparmelia

- Flavoplaca

- Flavopunctelia

- Flegographa

- Fluctua

- Follmannia

- Follmanniella

- Fominiella[68]

- Fouragea

- Franwilsia

- Frigidopyrenia

- Frutidella

- Fulgidea

- Fulvophyton

- Fuscidea

- Fuscoderma

- Fuscopannaria

- Gabura[42]

- Gassicurtia

- Geisleria

- Gibbosporina

- Gintarasia

- Gintarasiella[69]

- Glaucotrema

- Gloeheppia

- Glomerilla

- Glomerulophoron

- Glyphis

- Glypholecia

- Glyphopeltis

- Glyphopsis

- Glysoplaca

- Gomphillus

- Gondwania

- Gorgadesia

- Gossypiothallon

- Gowardia

- Granulopyrenis

- Graphidastra

- Graphis

- Gregorella

- Gudelia

- Gyalecta

- Gyalectaria

- Gyalectidium

- Gyalidea

- Gyalideopsis

- Gyalolechia

- Gymnoderma

- Gymnographa

- Gymnographopsis

- Gyrocollema

- Gyrographa

- Gyronactis

- Gyrotrema

- Haematomma

- Halecania

- Halegrapha

- Halographis

- Haloplaca

- Hanstrassia[70]

- Haplodina

- Haploloma

- Harpidium

- Harusavskia[71]

- Heiomasia

- Helicobolomyces[72][73]

- Helminthocarpon

- Helocarpon

- Hemithecium

- Henrica

- Heppia

- Heppsora

- Herpothallon

- Hertella

- Herteliana

- Hertelidea

- Heterocarpon

- Heterocyphelium

- Heterodermia

- Heteromyces

- Heteroplacidium

- Himantormia

- Hippocrepidea

- Homothecium

- Hormosphaeria

- Hosseusia

- Hosseusiella[74]

- Huea

- Hueidea

- Huneckia

- Hydropunctaria

- Hymenelia

- Hyperphyscia

- Hypocenomyce

- Hypoflavia

- Hypogymnia

- Hypotrachyna

- Icmadophila

- Igneoplaca

- Ikaeria[75]

- Immersaria

- Imshaugia

- Ingaderia

- Ingvariella

- Inoderma

- Involucropyrenium

- Ionaspis

- Ioplaca

- Isalonactis

- Jamesiella

- Japewia

- Japewiella

- Jarmania

- Jasonhuria

- Jenmania

- Joergensenia

- Josefpoeltia

- Julella[42]

- Kaernefeltia

- Kaernefia

- Kalbiana

- Kalbionora[76][77]

- Kalbographa

- Kashiwadia

- Kantvilasia

- Klauskalbia[78]

- Knightiella[42]

- Koerberia

- Koerberiella

- Krogia

- Kroswia

- Kuettlingeria

- Kurokawia[79]

- Labyrintha

- Lambiella

- Lasallia

- Lasioloma

- Lathagrium

- Lazarenkoella

- Lecanactis

- Lecania

- Lecanographa

- Lecanora (list)

- Lecidea (list)

- Lecidella

- Lecidoma

- Lecidopyrenopsis

- Leciophysma

- Leifidium

- Leightoniella

- Leimonis

- Leioderma

- Leiorreuma

- Lemmopsis

- Lempholemma

- Lendemeriella

- Lepidocollema

- Lepidostroma

- Lepra

- Leprantha

- Lepraria

- Leprocaulon

- Leprocollema

- Leproplaca

- Leptochidium

- Leptogidium

- Leptogium

- Leptorhaphis

- Leptotrema

- Letharia

- Lethariella

- Letrouitia

- Leucodecton

- Leucodermia

- Lichenomphalia

- Lichina

- Lichinella

- Lichinodium

- Lignoscripta

- Lithoglypha

- Lithographa

- Lithogyalideopsis

- Lithothelium

- Llimonaea

- Lobaria

- Lobariella

- Lobarina

- Lobothallia

- Loekoesia

- Loflammia

- Loflammiopsis

- Logilvia

- Lopacidia

- Lopadium

- Lopezaria

- Loxospora

- Loxosporopsis

- Lueckingia

- Lyromma

- Magmopsis

- Malcolmiella

- Malmidea

- Malmographina

- Mangoldia

- Marcelaria

- Marchandiomphalina

- Marchantiana

- Marfloraea

- Maronea

- Maronella

- Maronina[62][80]

- Masonhalea

- Massalongia

- Mastodia

- Mawsonia

- Mazaediothecium

- Mazosia

- Megalaria

- Megaloblastenia

- Megalospora

- Megalotremis

- Megaspora

- Melanelia

- Melanelixia

- Melanohalea

- Melanolecia

- Melanophloea

- Melanotopelia

- Melanotrema

- Melarthonis

- Melaspilea

- Menegazzia (list)

- Meridianelia

- Metamelanea

- Metus

- Micarea

- Microtheliopsis

- Milospium

- Miltidea

- Minksia

- Miriquidica

- Mischoblastia

- Mobergia

- Monerolechia

- Monoblastia

- Montanelia

- Moriola

- Multiclavula

- Multisporidea[81]

- Mycobilimbia

- Mycoblastus

- Mycoporum

- Myelochroa

- Myeloconis

- Myelorrhiza

- Myriolecis

- Myrionora

- Myriospora

- Myriostigma

- Myochroidea

- Nadvornikia

- Nebularia

- Neobrownliella[82]

- Neocatapyrenium

- Neophyllis

- Neopsoromopsis

- Neosergipea

- Nephroma

- Nephromopsis

- Nevesia

- Niebla

- Nigrovothelium

- Nipponoparmelia

- Nitidochapsa

- Nodobryoria

- Normandina

- Notocladonia

- Notolecidea

- Notoparmelia

- Novomicrothelia

- Nyungwea

- Obscuroplaca[83]

- Ocellomma

- Ocellularia (list)

- Ochrolechia

- Oevstedalia

- Olegblumia

- Oletheriostrigula

- Omphalodium

- Omphalora

- Opegrapha

- Opeltia[84]

- Ophioparma

- Orceolina

- Orcularia

- Orientophila

- Oropogon

- Orphniospora

- Oxnerella

- Pachnolepia

- Pachyascus

- Pachypeltis

- Pachyphysis

- Palicella

- Pallidogramme

- Pannaria

- Pannoparmelia

- Parabagliettoa

- Paracollema

- Paragyalideopsis[85][86]

- Paraingaderia

- Parainoa

- Paraporpidia

- Paraschismatomma

- Parasiphula

- Paratopeliopsis

- Paratricharia

- Parmelia

- Parmeliella

- Parmelina

- Parmelinella

- Parmeliopsis

- Parmostictina

- Parmotrema (list)

- Parmotremopsis

- Parvoplaca

- Paulia

- Peccania

- Pectenia

- Peltigera

- Peltula

- Peltularia

- Pentagenella

- Pertusaria (list)

- Petractis

- Phaeographis

- Phaeographopsis

- Phaeophyscia

- Phaeorrhiza

- Phloeopeccania

- Phlyctis

- Phoebus

- Phylliscidium

- Phyllisciella

- Phylliscidiopsis

- Phylliscum

- Phyllobaeis

- Phyllobathelium

- Phylloblastia

- Phyllocratera

- Phyllogyalidea

- Phyllopsora

- Physcia

- Physcidia

- Physciella

- Physconia

- Physma

- Piccolia

- Pilophorus

- Placidiopsis

- Placidium

- Placocarpus

- Placolecis

- Placomaronea

- Placopsis

- Placopyrenium

- Placothelium

- Placynthiella

- Placynthiopsis

- Placynthium

- Platismatia

- Platygramme

- Platythecium

- Plectocarpon

- Pleopsidium

- Pleurosticta

- Pliariona

- Podostictina

- Podotara

- Poeltiaria

- Poeltidea

- Poeltinula

- Polistroma

- Polyblastia

- Polyblastidium

- Polycauliona

- Polychidium

- Polymeridium

- Polypyrenula

- Polysporina

- Porina

- Porocyphus

- Porpidia

- Porpidinia[42]

- Protoblastenia

- Protomicarea

- Protopannaria

- Protoparmelia

- Protoparmeliopsis

- Protoroccella[42]

- Protothelenella

- Protousnea

- Psammina

- Psathyrophlyctis

- Pseudarctomia

- Pseudephebe

- Pseudevernia

- Pseudobaeomyces

- Pseudocalopadia

- Pseudochapsa

- Pseudocyphellaria

- Pseudohepatica

- Pseudoheppia

- Pseudolecanactis

- Pseudoleptogium

- Pseudopannaria

- Pseudoparmelia

- Pseudopaulia

- Pseudopeltula

- Pseudopyrenula

- Pseudoramonia

- Pseudosagedia

- Pseudoschismatomma

- Pseudothelomma

- Pseudotopeliopsis

- Psilolechia

- Psiloparmelia

- Psora

- Psorinia

- Psoroglaena

- Psoroma

- Psoromella

- Psoromidium[42]

- Psoronactis

- Psorotheciopsis

- Psorotichia

- Psorula

- Pterygiopsis

- Ptychographa

- Pulvinodecton

- Pulvinora[87]

- Punctelia

- Punctonora

- Puttea

- Pycnora

- Pycnothelia

- Pycnotrema

- Pyrenocarpon

- Pyrenocollema

- Pyrenodesmia

- Pyrenopsis

- Pyrenothrix

- Pyrenowilmsia

- Pyrenula (list)

- Pyrgillus

- Pyrrhospora

- Pyxine

- Racodium

- Racoleus

- Raesaeneniana

- Ramalea

- Ramalina

- Ramalodium

- Ramboldia

- Ramonia

- Redingeria

- Redonia

- Redonographa

- Rehmanniella[88]

- Reichlingia

- Reimnitzia

- Relicina

- Remototrachyna

- Requienella

- Rhabdodiscus

- Rhabdopsora

- Rhaphidicyrtis

- Rhexophiale

- Rhizocarpon

- Rhizolecia

- Rhizoplaca

- Ricasolia

- Rimularia

- Rinodina (list)

- Rinodinella

- Robergea

- Rocella

- Roccellographa

- Roccellina

- Roccellinastrum

- Rockefellera[89]

- Rolfidium

- Rolueckia

- Romjularia

- Ropalospora

- Rostania

- Rubrotricha

- Rufoplaca

- Rusavskia

- Sagedia

- Sagema

- Sagenidiopsis

- Sagiolechia

- Sanguinotrema

- Santessonia

- Sarcographa

- Sarcographina

- Sarcogyne

- Sarcosagium

- Sarea

- Sarrameana

- Savoronala

- Schadonia

- Schaereria

- Schismatomma

- Schistophoron

- Schizodiscus

- Schizopelte

- Schizotrema

- Schizoxylon

- Sclerococcum

- Sclerophora

- Sclerophyton

- Scleropyrenium

- Scoliciosporum

- Sculptolumina

- Scutaria

- Scytinium

- Sedelnikovaea

- Segestria

- Seirophora

- Semigyalecta

- Semiomphalina

- Septotrapelia

- Servitia

- Shackletonia

- Sigridea

- Simonyella

- Sipmaniella

- Siphula

- Siphulastrum

- Siphulella

- Sipmania

- Sirenophila

- Snippocia[90][73]

- Solenopsora

- Solitaria

- Solorina

- Solorinaria

- Sparria

- Speerschneidera

- Sphaerophorus

- Sphaerophoropsis

- Spheconisca

- Sphinctrinopsis

- Spilonema

- Sporastatia

- Sporodictyon

- Sporodophoron

- Sporopodiopsis

- Sporopodium

- Sporostigma

- Sprucidea[91][80]

- Squamarina

- Squamella

- Squamulea

- Staurospora[92][93]

- Staurolemma

- Staurothele

- Stegobolus

- Steinera

- Steineropsis

- Steinia

- Stellarangia

- Stenhammarella

- Stephanocyclos

- Stereocaulon

- Sticta

- Stictis

- Stigmatochroma

- Stigmidium

- Strangospora

- Streimannia

- Streimanniella

- Stirtonia

- Stirtoniella

- Strigula

- Stromatella

- Sulcaria

- Sulcopyrenula

- Sulzbacheromyces

- Synalissa

- Synarthonia

- Synarthothelium

- Syncesia

- Szczawinskia

- Tania

- Tapellaria

- Tapellariopsis

- Tarasginia

- Tarbertia

- Tasmidella

- Tassiloa

- Tayloriellina

- Teloschistes

- Teloschistopsis

- Tenuitholiascus[94][45]

- Tephromela

- Tetramelas

- Teuvoa

- Texosporium

- Thallinocarpon

- Thalloloma

- Thamnochrolechia

- Thamnolecania

- Thamnolia

- Thecaria

- Thecographa

- Thelenella

- Thelenidia

- Thelidiopsis

- Thelignya

- Thelliana

- Thelocarpon

- Thelomma

- Thelopsis

- Thelotrema

- Thermutis

- Thermutopsis

- Tholurna

- Thrombium

- Thyrea

- Thysanothecium

- Tibellia

- Timdalia

- Tingiopsidium

- Toensbergia

- Toninia

- Toniniopsis

- Topelia

- Topeliopsis

- Tornabea

- Trapelia

- Trapeliopsis

- Traponora

- Tremolecia

- Tremotylium[42]

- Tricharia

- Trichothelium

- Trimmatothele

- Trimmatothelopsis

- Trinathotrema

- Trizodia

- Trypetheliopsis

- Trypethelium

- Tuckermanella

- Tuckermanopsis

- Tylophorella

- Tylophoron

- Tylophoropsis

- Tylothallia

- Umbilicaria

- Upretia[95]

- Usnea

- Usnocetraria

- Usnochroma

- Vahliella

- Vainionora

- Varicellaria

- Variospora

- Verrucaria (list)

- Verruculopsis

- Verseghya[96]

- Vezdaea

- Vigneronia

- Villophora

- Violella

- Viridothelium

- Vulpicida

- Wadeana

- Wahlenbergiella

- Watsoniomyces[97]

- Wawea

- Waynea

- Wetmoreana

- Willeya

- Wirthiotrema

- Xalocoa

- Xanthocarpia

- Xanthomendoza

- Xanthoparmelia (list)

- Xanthopeltis

- Xanthopsorella

- Xanthoria

- Xenolecia

- Xenus

- Xyleborus

- Xylographa

- Xyloschistes

- Xylospora

- Yarrumia

- Yoshimuria

- Yoshimuriella

- Zahlbrucknerella

- Zeroviella

- Zwackhia

Species

In 2009, taxonomists estimated that the total number of lichen species (including those yet undiscovered) might be as high as 28,000.[98] By 2016, 19,387 species of lichens had been described and widely accepted.[99]

Lichens, by growth form

Lichen growth forms – These vary depending on the species:

- Crustose – paint-like appearance that adheres tightly to the underlying substrate.[101]

- Foliose – flattened, leafy appearance.[102]

- Fruticose – shrubby, bush-like or coral-like appearance.[102]

- Gelatinous – jelly-like interior, due to presence of cyanobacteria.[106]

- Squamulose – scaly, sometimes leafy appearance; can resemble a foliose lichen but usually has no outer cortex.[107]

- Cladoniform – squamulose, but with fruticose podetia.[108]

Lichens, by substrate

Lichens can be classified by the substrate on which they grow:

- Bryophilous lichen – on mosses or liverworts.[109]

- Corticolous lichen – on bark.[109]

- Ramicolous lichen – on twigs.[111]

- Foliicolous lichen – on plant leaves.[109]

- Lichenicolous lichen – on other lichens.[109]

- Lignicolous lichen – on wood stripped of bark.[109]

- Omnicolous lichen – on a variety of substrates.[111]

- Plasticolous lichen – on plastic.[113]

- Saxicolous lichen – on stone.[109]

- Endolithic lichen – within stone.[22]

- Terricolous lichen – on soil.[111]

- Vagrant lichen – loose, on no substrate.[114]

Lichens, by region

Africa

- List of lichens of Madagascar

- List of lichens of Namibia

Antarctica

Asia

- List of lichens of Sri Lanka

Australia

- List of lichens of Western Australia

Europe

- List of lichens of Sweden

North America

- List of lichens of Maryland

- List of lichens of Soldiers Delight – lichens of a nature reserve in Maryland

- List of lichen species of Montana

- Lichens of the Sierra Nevada (U.S.)

Oceania

Pacific

South America

Photobiont

Photobiont – the photosynthetic partner in a lichen.[116]

- Cyanolichen – a lichen with a cyanobacteria photobiont.[117]

- List of lichen photobionts

Lichen metabolites

Lichen product – organic products, known as secondary metabolites, produced by lichens; these provide a variety of protections for the lichen – from microbes, viruses, herbivores, radiation, oxidants and more.[118]

- List of lichen products

Study of lichens

Lichenology – the study of lichens.[120]

- Acharius Medal – awarded for lifetime achievement in lichenology.[121]

- Evolution of lichens – lichenization of fungi has occurred multiple times, and several pathways towards acquiring photobionts have arisen.

- List of fossil lichens

- Exsiccata (plural exsiccatae) – a published set of preserved specimens, numbered and distributed with printed labels.[122]

- History of lichenology

- Lichenometry – a process where measuring the growth of a lichen colony over time can be used to estimate the minimum age of the substrate on which it is growing.[123]

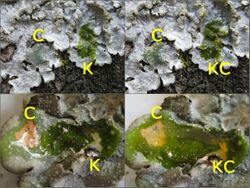

- Spot test (lichen) – chemical tests used to aid in species identification.[124]

Threats

- Lichenicolous fungus – parasitic fungus that uses lichens as a host.[125]

- List of lichenicolous fungi

- Lichens as bioindicators – lichens are sensitive to various pollutants and can be thus be used as bioindicators.[126]

Lichens in culture

- Cultural depictions of lichens

- Trouble with Lichen – science fiction novel by John Wyndham in which lichens play a major role.[130]

- Edible lichen – some lichens have traditionally been used as food.[131]

- Ethnolichenology – a branch of ethnobotany that studies human usage of lichens.[132]

Lichen organizations

- The Bryologist – peer-reviewed journal published by ABLS.

- Australasian Lichen Society

- Australasian Lichenology – official publication of the Australasian Lichen Society.

- British Lichen Society (BLS)

- The Lichenologist – peer-reviewed journal published by the BLS.

- Bryological and Lichenological Association for Central Europe (BLAM)

- Herzogia – peer-reviewed journal published by BLAM.

- Bryological and Lichenological Working Group (Bryologische en Lichenologische Werkgroep, BLWG)

- Buxbaumiella – peer-reviewed journal published by BLWG.

- Dutch Bryological and Lichenological Society

- Lindbergia – peer-reviewed journal co-published by the Dutch Bryological and Lichenological Society and the Nordic Bryological Society.

- Indian Lichenological Society

- International Association for Lichenology (IAL)

- Nordic Bryological Society

Independent lichenological journals

- Asian Journal of Mycology – an international peer-reviewed journal published by Mae Fah Luang University in Thailand.

- Bibliotheca Lichenologica – scientific monographs on lichens and mosses.

- Hattoria – an international, peer-reviewed journal issued by Hattori Botanical Laboratory.

- International Journal of Mycology and Lichenology

See also

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Van Hoose 2021.

- ↑ Cambridge Dictionary.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Favor 2005, p. 5.

- ↑ Laundon 1986, p. 3.

- ↑ Li et al. 2021, p. evab101.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Purvis 2000, p. 9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Laundon 1986, p. 2.

- ↑ Honegger 1998, p. 197.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 758.

- ↑ Baron 1999, p. 14.

- ↑ Hawksworth, Sutton & Ainsworth 1983, p. 26.

- ↑ Silverstein, Silverstein & Silverstein 1996, p. 32.

- ↑ Smith et al. 2009, p. 22.

- ↑ Smith et al. 2009, p. 30.

- ↑ Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 756.

- ↑ Hale 1983, pp. 3, 6.

- ↑ Smith et al. 2009, p. 36.

- ↑ Smith et al. 2009, p. 24.

- ↑ Hawksworth, Sutton & Ainsworth 1983, p. 330.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Smith et al. 2009, p. 38.

- ↑ Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 763.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 757.

- ↑ Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 759.

- ↑ Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 760.

- ↑ Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 761.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Henriksson & Simu 1971, p. 119.

- ↑ Smith et al. 2020, p. 134.

- ↑ Bowler & Rundel 1975, p. 328.

- ↑ Bowler & Rundel 1975, p. 326–327.

- ↑ Galloway 2012, p. 315.

- ↑ Zakeri et al. 2022, p. 80.

- ↑ Chen, Blume & Beyer 2000, p. 124.

- ↑ Green et al. 2018, p. 397.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Wijayawardene et al. 2022.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Lücking, Hodkinson & Leavitt 2016, p. 377–400.

- ↑ Bendre 2010, p. 131.

- ↑ Lepp 2014.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Lücking, Hodkinson & Leavitt 2016, p. 371.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Kraichak et al. 2018a.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Kraichak et al. 2018b.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 Wijayawardene et al. 2022, p. 162.

- ↑ 42.00 42.01 42.02 42.03 42.04 42.05 42.06 42.07 42.08 42.09 42.10 Lücking, Hodkinson & Leavitt 2017, p. 58.

- ↑ Gamundí & Spinedi 1985, p. 112.

- ↑ Jiang et al. 2020, p. 11.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Wijayawardene et al. 2022, p. 124.

- ↑ Lendemer, Harris & Ruiz 2016, p. 26.

- ↑ Lücking & Kalb 2018, p. 353.

- ↑ Wilk et al. 2021, p. 289.

- ↑ Aptroot, Sparrius & Alvarado 2018, p. 12.

- ↑ Wilk et al. 2021, p. 292.

- ↑ Spribille et al. 2020, p. 85.

- ↑ Kantvilas, Wedin & Svensson 2021, p. 400.

- ↑ Divakar et al. 2017, p. 110.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Wijayawardene et al. 2022, p. 150.

- ↑ Diederich & Ertz 2020, p. 22.

- ↑ Kistenich et al. 2018, p. 871.

- ↑ Fryday et al. 2020, p. 473.

- ↑ Wilk et al. 2021, p. 293.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2019, p. 295.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2017, p. 79.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Wijayawardene et al. 2022, p. 156.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Divakar et al. 2017, p. 109.

- ↑ Ertz et al. 2017, p. 131.

- ↑ Wijayawardene et al. 2022, p. 159.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2017, p. 86.

- ↑ Simon et al. 2020, p. 82.

- ↑ Sobreira et al. 2018, p. 67.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2017, p. 87.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2017, p. 90.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2017, p. 91.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2017, p. 96.

- ↑ Grube, Matzer & Hafellner 1995, p. 28.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Wijayawardene et al. 2022, p. 89.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2018, p. 97.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2017, p. 105.

- ↑ Wijayawardene et al. 2022, p. 98.

- ↑ Sodamuk et al. 2017, p. 15.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2021, p. 372.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2021, p. 375.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Wijayawardene et al. 2022, p. 149.

- ↑ Kalb & Aptroot 2021, p. 5.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2015, p. 328.

- ↑ Bungartz, Søchting & Arup 2021.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2017, p. 112.

- ↑ Etayo 2017, p. 335.

- ↑ Wijayawardene et al. 2022, p. 160.

- ↑ Davydov et al. 2021, p. 245.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2018, p. 107.

- ↑ Lendemer, Stone & Tripp 2017, p. 459.

- ↑ Ertz et al. 2018, p. 170.

- ↑ Cáceres et al. 2017, p. 206.

- ↑ Wijayawardene et al. 2022, p. 38.

- ↑ Grube 2018, p. 695.

- ↑ Jiang et al. 2020, p. 1.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2018, p. 24.

- ↑ Kondratyuk et al. 2016, p. 104.

- ↑ Díaz-Escandón et al. 2021, p. 501.

- ↑ Lücking et al. 2009, p. 411.

- ↑ Lücking, Hodkinson & Leavitt 2016, p. 370.

- ↑ Dobson 2011, p. 470.

- ↑ Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 16.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 102.3 102.4 The British Lichen Society 2022a.

- ↑ Temu et al. 2019, p. 1.

- ↑ Kantvilas 1996, p. 229.

- ↑ Dobson 2011, p. 26.

- ↑ Sanders 2001, p. 1033.

- ↑ Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 17.

- ↑ Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 18.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 109.2 109.3 109.4 109.5 109.6 The British Lichen Society 2022b.

- ↑ Lendemer, Buck & Harris 2016, p. 441.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 111.2 111.3 Upreti & Rai 2013, p. 2.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Lücking 2008, p. 4.

- ↑ Lücking 1998, p. 287.

- ↑ Rosentreter 1993, p. 333.

- ↑ Schultz, Zedda & Rambold 2009, p. 315.

- ↑ Purvis 2000, p. 5.

- ↑ Rikkinen 2015, p. 973.

- ↑ Goga et al. 2018, p. 1.

- ↑ Truong & Clerc 2003, p. 52.

- ↑ Merriam-Webster.

- ↑ International Association for Lichenology.

- ↑ Pfister 1985, p. 1.

- ↑ Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 84.

- ↑ Brodo, Sharnoff & Sharnoff 2001, p. 103.

- ↑ Lawrey & Diederich 2003, p. 80.

- ↑ Nimis, Scheidegger & Wolseley 2002.

- ↑ Oliver 2011, p. 1.

- ↑ Field Museum 2022.

- ↑ Turner 1977, p. 461.

- ↑ Penguin Books.

- ↑ Ivanova & Ivanov 2009, p. 11.

- ↑ Vinayaka & Krishnamurthy 2012, p. 265.

References

- Aptroot, A.; Sparrius, L.B.; Alvarado, P. (2018). "Aquacidia, a new genus to accommodate a group of skiophilous temperate Bacidia species that belong in the Pilocarpaceae (lichenized ascomycetes)". Gorteria 40: 11–14. ISSN 2542-8578. https://docslib.org/doc/1468194/aquacidia-a-new-genus-to-accommodate-a-group-of-skiophilous-temperate-bacidia-species-that-belong-in-the-pilocarpaceae-lichenized-ascomycetes.

- "Awards". International Association for Lichenology. http://www.lichenology.org/index.html?/Awards/Awards.html.

- Baron, George (1999). Understanding Lichens. Slough: Richmond Publishing. ISBN 978-0-85546-252-9.

- Bendre, Ashok M. (2010). A Text Book of Practical Botany. New Dehli: Rastogi Publications. ISBN 978-81-7133-923-5.

- Bowler, P. A.; Rundel, P. W. (June 1975). "Reproductive strategies in lichens". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 70 (4): 325–340. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1975.tb01653.x. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230018293.

- Brodo, Irwin M.; Sharnoff, Sylvia Duran; Sharnoff, Stephen (2001). Lichens of North America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08249-4. https://archive.org/details/lichensofnortham0000brod/mode/2up.

- Bungartz, F.; Søchting, U.; Arup, U. (December 2021). "Obscuroplaca gen. nov. – a replacement name for Phaeoplaca; Teloschistaceae (lichenized Ascomycota) from the Galapagos Islands". Plant and Fungal Systematics 66 (2): 240–241. doi:10.35535/pfsyst-2021-0022.

- Cáceres, Marcela Eugenia da Silva; Aptroot, André; Mendonça, Cléverton Oliveira; Santos, Lidiane Alves; Lücking, Robert (2017). "Sprucidea, a further new genus of rain forest lichens in the family Malmideaceae (Ascomycota)". Bryologist 120 (2): 202–211. doi:10.1639/0007-2745-120.2.202.

- Chen, Jie; Blume, Hans-Peter; Beyer, Lothar (March 2000). "Weathering of rocks induced by lichen colonization — a review". Catena 39 (2): 121–146. doi:10.1016/S0341-8162(99)00085-5.

- Davydov, Evgeny A.; Yakovchenko, Lidia S.; Hollinger, Jason; Bungartz, Frank; Parrinello, Christian; Printzen, Christian (2021). "The new genus Pulvinora (Lecanoraceae) for species of the 'Lecanora pringlei' group, including the new species Pulvinora stereothallina". The Bryologist 124 (2): 242–256. doi:10.1639/0007-2745-124.2.242. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/351294022.

- Díaz-Escandón, David; Hawksworth, David L.; Powell, Mark; Resl, Philipp; Spribille, Toby (February 2021). "The British chalk specialist Lecidea lichenicola auct. revealed as a new genus of Lichinomycetes". Fungal Biology 125 (7): 495–504. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2021.01.007. PMID 34140146.

- Diederich, Paul; Ertz, Damien (2020). "First checklist of lichens and lichenicolous fungi from Mauritius, with phylogenetic analyses and description of new taxa". Plant and Fungal Systematics 65 (1): 13–75. doi:10.35535/pfsyst-2020-0003.

- Divakar, Pradeep K.; Crespo, Ana; Kraichak, Ekaphan; Leavitt, Steven D.; Singh, Garima; Schmitt, Imke; Lumbsch, H. Thorsten (2017). "Using a temporal phylogenetic method to harmonize family- and genus-level classification in the largest clade of lichen-forming fungi". Fungal Diversity 84: 101–117. doi:10.1007/s13225-017-0379-z.

- Dobson, Frank S. (2011). Lichens: An Illustrated Guide to the British and Irish Species. Slough, UK: Richmond Publishing Co.. ISBN 978-0-85546-316-8.

- Ertz, Damien; Søchting, Ulrik; Gadea, Alice; Charrier, Maryvonne; Poulsen, Roar S. (2017). "Ducatina umbilicata gen. et sp. nov., a remarkable Trapeliaceae from the subantarctic islands in the Indian Ocean". The Lichenologist 49 (2): 127–140. doi:10.1017/s0024282916000700.

- Ertz, Damien; Sanderson, Neil; Łubek, Anna; Kukwa, Martin (March 2018). "Two new species of Arthoniaceae from old-growth European forests, Arthonia thoriana and Inoderma sorediatum, and a new genus for Schismatomma niveum". The Lichenologist 50 (2): 161–172. doi:10.1017/S0024282917000688.

- Etayo, Javier (2017) (in Spanish). Hongos liquenícolas de Ecuador. Opera Lilloana. San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina: Fundación Miguel Lillo. https://www.lillo.org.ar/revis/opera-lilloana/2017-opl-v50.pdf.

- Favor, Lesli J. (2005). Eukaryotic and Prokaryotic Cell Structures: Understanding Cells with and Without a Nucleus. New York: Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4042-0323-5.

- Field Museum (15 February 2022). "Lichens are in danger of losing the evolutionary race with climate change". https://phys.org/news/2022-02-lichens-danger-evolutionary-climate.html.

- Fryday, Alan M.; Medeiros, Ian D.; Siebert, Stefan J.; Pope, Nathaniel; Rajakaruna, Nishanta (2020). "Burrowsia, a new genus of lichenized fungi (Caliciaceae), plus the new species B. cataractae and Scoliciosporum fabisporum, from Mpumalanga, South Africa". South African Journal of Botany 132: 471–481. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2020.06.001.

- Galloway, D. J. (2012). "Lichen biogeography". in Nash III, Thomas H.. Lichen Biology. Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 315–335. ISBN 978-0-521-69216-8.

- Gamundí, Irma J.; Spinedi, H. A. (1985). "Phaneromyces Speg. & Hariot, a discomycetous genus of critical taxonomic position". Sydowia 38: 106–113. https://www.zobodat.at/pdf/Sydowia_38_0106-0113.pdf.

- "Glossary of Terms". The British Lichen Society. 2022b. https://britishlichensociety.org.uk/learning/glossary-terms.

- Goga, Michal; Elečko, Ján; Marcinčinová, Margaréta; Ručová, Dajana; Bačkorová, Miriam; Bačkor, Martin (2018). "Lichen Metabolites: An Overview of Some Secondary Metabolites and Their Biological Potential". in Merillon, J. M.; Ramawat, K.. Bioactive Molecules in Food. Reference Series in Phytochemistry. Springer, Cham. pp. 1–36. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-76887-8_57-1. ISBN 978-3-319-76887-8.

- Green, T. G. Allen; Pintado, Ana; Raggio, Jose; Sancho, Leopoldo Garcia (May 2018). "The lifestyle of lichens in soil crusts". The Lichenologist 50 (3): 397–410. doi:10.1017/S0024282918000130.

- Grube, M.; Matzer, M.; Hafellner, J. (January 1995). "A Preliminary Account of the Lichenicolous Arthonia Species with Reddish, K+ Reactive Pigments". The Lichenologist 27 (1): 25–42. doi:10.1006/lich.1995.9999. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/231757718.

- Grube, Martin (October 2018). "Staurospora, a new genus for a unique species with spherical ascospores in Arthoniaceae". Herzogia 31 (p1): 695–699. doi:10.13158/heia.31.1.2018.695.

- Hale, Mason E., ed (1983). The Biology of Lichens (3rd ed.). London: Edward Arnold Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7131-2867-3. https://archive.org/details/biologyoflichens0000hale/mode/2up.

- Hawksworth, David Leslie; Sutton, Brian Charles; Ainsworth, Geoffrey Clough, eds (1983). Ainsworth & Bisby's dictionary of the fungi, including lichens (7th ed.). Kew, Surrey: Commonwealth Mycological Institute. ISBN 978-0-85198-515-2. https://archive.org/details/ainsworthbisbysd0007ains/mode/2up.

- Henriksson, Elisabet; Simu, Barbro (1971). "Nitrogen Fixation by Lichens". Oikos 22 (1): 119–121. doi:10.2307/3543371.

- Honegger, Rosmarie (May 1998). "The Lichen Symbiosis – What is so Spectacular about it?". The Lichenologist 30 (3): 193–212. doi:10.1017/s002428299200015x. https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/154903/1/ZORA_NL_154903.pdf.

- Ivanova, Diana; Ivanov, Dobri (2009). "Ethnobotanical use of lichens: lichens for food review". Scripta Scientifica Medica 41 (1): 11–16. doi:10.14748/ssm.v41i1.456.

- Jiang, Shu Hua; Hawksworth, David L.; Lücking, Robert; Wei, Jiang Chun (2020). "A new genus and species of foliicolous lichen in a new family of Strigulales (Ascomycota: Dothideomycetes) reveals remarkable class-level homoplasy". IMA Fungus 11 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1186/s43008-019-0026-2. PMID 32617253.

- Kalb, Klaus; Aptroot, André (2021). "New lichens from Africa". Archive for Lichenology 28: 1–12. http://www.fschumm.de/Archive/Vol%2028_Kalb_new%20records%20Africa.pdf.

- Kantvilas, Gintaras (May 1996). "A new byssoid lichen genus from Tasmania". The Lichenologist 28 (3): 229–237. doi:10.1006/lich.1996.0020. http://nhm2.uio.no/botanisk/lav/RLL/PDF2/Lichenologist/28/28_229-237.pdf.

- Kantvilas, Gintaras; Wedin, Mats; Svensson, Måns (September 2021). "Australidea (Malmideaceae, Lecanorales), a new genus of lecideoid lichens, with notes on the genus Malcolmiella". The Lichenologist 53 (5): 395–407. doi:10.1017/s0024282921000311.

- Kondratyuk, S.Y.; Kärnefelt, I.; Thell, A.; Elix, J.A.; Kim, J.; Kondratiuk, A. S.; Hur, J.-S. (2015). "Brownlielloideae, a new subfamily in the Teloschistaceae (Lecanoromycetes, Ascomycota)". Acta Botanica Hungarica 57 (3–4): 321–343. doi:10.1556/034.57.2015.3-4.6. http://real.mtak.hu/36989/1/034.57.2015.3-4.6.pdf.

- Kondratyuk, S.Y.; Lőkös, L.; Halda, J.P.; Haji Moniri, M.; Farkas, E.; Park, J.S.; Lee, B.G.; Oh, S.O. et al. (2016). "New and noteworthy lichen-forming and lichenicolous fungi 4". Acta Botanica Hungarica 58 (1–2): 75–136. doi:10.1556/034.58.2016.1-2.4. https://docslib.org/doc/9179505/new-and-noteworthy-lichen-forming-and-lichenicolous-fungi-4.

- Kondratyuk, S.Y.; Lőkös, L.; Upreti, D. K.; Nayaka, S.; Mishra, G.K.; Ravera, S.; Jeong, M.-H.; Jang, S.-H. et al. (2017). "New monophyletic branches of the Teloschistaceae (lichen-forming Ascomycota) proved by three gene phylogeny". Acta Botanica Hungarica 59 (1–2): 71–136. doi:10.1556/034.59.2017.1-2.6. http://real.mtak.hu/50370/1/034.59.2017.1-2.6.pdf.

- Kondratyuk, S.Y.; Persson, P.-E.; Hansson, M.; Lőkös, L.; Liu, D.; Hur, J.-S.; Kärnefelt, I.; Thell, A. (2018). "Hosseusiella and Rehmanniella, two new genera in the Teloschistaceae". Acta Botanica Hungarica 60 (1–2): 89–113. doi:10.1556/034.60.2018.1-2.7. http://real.mtak.hu/79024/1/034.60.2018.1-2.7.pdf.

- Kondratyuk, S.Y.; Persson, P.E.; Hansson, M.; Mishra, G.K.; Nayaka, S.; Liu, D.; Hur, J.S.; Thell, A. (2018). "Upretia, a new caloplacoid lichen genus (Teloschistaceae, lichen-forming Ascomycota) from India". Cryptogam Biodiversity and Assessment S2018: 22–31. doi:10.21756/cab.esp5. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322739723.

- Kondratyuk, S. Y.; Lőkös, L.; Farkas, E.; Jang, S.-H.; Liu, D.; Halda, J.; Persson, P.-E.; Hansson, M. et al. (2019). "Three new genera of the Ramalinaceae (lichen-forming Ascomycota) and the phenomenon of presence of 'extraneous mycobiont DNA' in lichen associations". Acta Botanica Hungarica 61 (3–4): 275–323. doi:10.1556/034.61.2019.3-4.5. http://real.mtak.hu/106748/1/034.61.2019.3-4.5.pdf.

- Kondratyuk, S.Y.; Lőkös, L.; Kärnefelt, I.; Thell, A.; Jeong, M.-H.; Oh, S.-O.; Kondratiuk, A.S.; Farkas, E. et al. (2021). "Contributions to molecular phylogeny of lichen-forming fungi 2. Review of current monophyletic branches of the family Physciaceae". Acta Botanica Hungarica 63 (3–4): 351–390. doi:10.1556/034.63.2021.3-4.8. http://real.mtak.hu/143270/1/article-p351.pdf.

- Kraichak, E.; Huang, J.P.; Nelsen, M.; Leavitt, S.D.; Lumbsch, H.T. (2018). "A revised classification of orders and families in the two major subclasses of Lecanoromycetes (Ascomycota) based on a temporal approach.". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 20: 1–17. doi:10.1093/botlinnean/boy060/5091569. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327542144.

- Kraichak, E.; Huang, J.P.; Nelsen, M.; Leavitt, S.D.; Lumbsch, H.T. (12 September 2018). "Nomenclatural novelties". Index Fungorum 375: 1. ISSN 2049-2375. http://www.indexfungorum.org/Publications/Index%20Fungorum%20no.375.pdf.

- Kistenich, Sonja; Timdal, Einar; Bendiksby, Mika; Ekman, Stefan (2018). "Molecular systematics and character evolution in the lichen family Ramalinaceae (Ascomycota: Lecanorales)". Taxon 67 (5): 871–904. doi:10.12705/675.1.

- Laundon, Jack R. (1986). Lichens. Shire Natural History series. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-85263-811-8. https://archive.org/details/lichens0000laun/mode/2up?q=cortex.

- Lawrey, James D.; Diederich, Paul (Spring 2003). "Lichenicolous Fungi: Interactions, Evolution, and Biodiversity". The Bryologist 106 (1): 80–120. doi:10.1639/0007-2745(2003)106[0080:LFIEAB2.0.CO;2].

- Lendemer, James; Harris, Richard C.; Ruiz, Ana Maria (March 2016). "A Review of the Lichens of the Dare Regional Biodiversity Hotspot in the Mid-Atlantic Coastal Plain of North Carolina, Eastern North America". Castanea 81 (1): 1–77. doi:10.2179/15-073R2. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303094334.

- Lendemer, James C.; Buck, William R.; Harris, Richard C. (September 2016). "Two new host-specific hepaticolous species of Catinaria (Ramalinaceae)". The Lichenologist 48 (5): 441–449. doi:10.1017/S0024282916000438.

- Lendemer, James C.; Stone, Heather B.; Tripp, Erin A. (2017). "Taxonomic delimitation of the rare, eastern North American endemic lichen Santessoniella crossophylla (Pannariaceae)". The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 144 (4): 459–468. doi:10.3159/torrey-d-16-00009.1.

- Lepp, Heino (2014). "Basidiolichens". Australian National Herbarium and Australian National Botanic Gardens. https://www.anbg.gov.au/lichen/basidiolichens.html.

- Li, Xi; Hou, Zheng; Xu, Chenjie; Shi, Xuan; Yang, Lingxiao; Lewis, Louise A.; Zhong, Bojian (July 2021). "Large Phylogenomic Data sets Reveal Deep Relationships and Trait Evolution in Chlorophyte Green Algae". Genome Biology and Evolution 13 (7): 329–332. doi:10.1093/gbe/evab101. PMID 8271138.

- "Lichen". Cambridge Dictionary. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/pronunciation/english/lichen.

- "Lichen Morphology". The British Lichen Society. 2022a. https://britishlichensociety.org.uk/learning/lichen-morphology.

- "Lichenology". Merriam-Webster. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lichenology.

- Lücking, Robert (May 1998). "'Plasticolous' Lichens in a Tropical Rain Forest at La Selva Biological Station, Costa Rica". The Lichenologist 30 (3): 287–291. doi:10.1006/lich.1998.0124.

- Lücking, Robert (2008). "Foliicolous Lichenized Fungi". Flora Neotropica 103: 1–866. ISSN 0071-5794. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25660968.

- Lücking, Robert; Hodkinson, Brendan P.; Leavitt, Steven D. (Winter 2016). "The 2016 classification of lichenized fungi in the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota–Approaching one thousand genera". The Bryologist 119 (4): 361–416. doi:10.1639/0007-2745-119.4.361.

- Lücking, Robert; Hodkinson, Brendan P.; Leavitt, Steven D. (2017). "Corrections and amendments to the 2016 classification of lichenized fungi in the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota". The Bryologist 120 (1): 58–69. doi:10.1639/0007-2745-120.1.058.

- Lücking, Robert; Kalb, Klause (2018). "Formal instatement of Allographa (Graphidaceae): how to deal with a hyperdiverse genus complex with cryptic differentiation and paucity of molecular data". Herzogia 31 (p1): 535–561. doi:10.13158/heia.31.1.2018.535.

- Lücking, Robert; Rivas-Plata, E; Chavez, JL; Umaña, L; Sipman, HJM (2009). "How many tropical lichens are there… really?". Bibliotheca Lichenologica 100: 399–418.

- Nimis, Pier Luigi; Scheidegger, Christoph; Wolseley, Patricia A., eds (2002). Monitoring with Lichens - Monitoring Lichens. 7. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business. ISBN 978-94-010-0423-7.

- Oliver, Mary (March 2011). "Canaries in a coal mine: using lichens to measure nitrogen pollution". Science Findings (USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station) 131. https://www.fs.usda.gov/pnw/sciencef/scifi131.pdf.

- Pfister, Donald H. (1985). "A bibliographic account of exsiccatae containing fungi". Mycotaxon 23: 1–139. http://www.cybertruffle.org.uk/cyberliber/59575/0023/0001.htm.

- Purvis, William (2000). Lichens. Life Series. London: The Natural History Museum. ISBN 978-0-565-09153-8. https://archive.org/details/lichens00purv.

- Rikkinen, Jouko (April 2015). "Cyanolichens". Biodiversity and Conservation 24 (4): 973–993. doi:10.1007/s10531-015-0906-8.

- Rosentreter, Roger (Autumn 1993). "Vagrant Lichens in North America". The Bryologist 96 (3): 333–338. doi:10.2307/3243861.

- Sanders, William B. (December 2001). "Lichens: the interface between mycology and plant morphology". BioScience 51 (12): 1025–1035. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[1025:LTIBMA2.0.CO;2].

- Schultz, Matthias; Zedda, Luciana; Rambold, Gerhard (2009). "New records of lichen taxa from Namibia and South Africa Bibliotheca Lichenologica". in Aptroot, André; Seaward, Mark R.D.; Sparrius, Laurens B.. Biodiversity and ecology of lichens – Liber Amicorum Harrie Sipman. 99. Berlin and Stuttgart: J. Cramer. pp. 315–334. http://www.bayceer.uni-bayreuth.de/mm/en/pub/pub/66767/Schultz-BL99-315-334.pdf.

- Silverstein, Alvin; Silverstein, Virginia B.; Silverstein, Robert A. (1996). Fungi. New York: Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-3520-9. https://archive.org/details/fungisilv00silv/mode/2up.

- Simon, Antoine; Lücking, Robert; Moncada, Bibiana; Mercado-Díaz, Joel A.; Bungartz, Frank; da Silva Cáceres, Marcela Eugenia; Gumboski, Emerson Luiz; de Azevedo Martins, Suzana Maria et al. (2020). "Emmanuelia, a new genus of lobarioid lichen-forming fungi (Ascomycota: Peltigerales): phylogeny and synopsis of accepted species". Plant and Fungal Systematics 65 (1): 76–94. doi:10.35535/pfsyst-2020-0004.

- Smith, C. W.; Aptroot, A.; Coppins, B. J. et al., eds (2009). The Lichens of Great Britain and Ireland. London: The British Lichen Society. ISBN 978-0-9540418-8-5.

- Smith, Hayden B.; Dal Grande, Francesco; Muggia, Lucia; Keuler, Rachel; Divakar, Pradeep K.; Grewe, Felix; Schmitt, Imke; Lumbsch, H. Thorsten et al. (November 2020). "Metagenomic data reveal diverse fungal and algal communities associated with the lichen symbiosis". Symbiosis 82 (1–2): 133–147. doi:10.1007/s13199-020-00699-4.

- Sobreira, Priscylla Nayara Bezerra; Cáceres, Marcela Eugenia Da Silva; Maia, Leonor Costa; Lücking, Robert (July 2018). "Flabelloporina, a new genus in the Porinaceae (Ascomycota, Ostropales), with the first record of F. squamulifera from Brazil". Phytotaxa 538 (1): 67–75. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.358.1.4.

- Sodamuk, Mattika; Boonpragob, Kansri; Mongkolsuk, Pachara; Tehler, Andrs; Leavitt, Steven D.; Lumbsch, H. Thorsten (2017). "Kalbionora palaeotropica, a new genus and species from coastal forests in Southeast Asia and Australia (Malmideaceae, Ascomycota)". MycoKeys 22: 15–25. doi:10.3897/mycokeys.22.12528.

- Spribille, Toby; Fryday, Alan M.; Pérez-Ortega, Sergio; Svensson, Måns; Tønsberg, Tor; Ekman, Stefan; Holien, Håkon; Resl, Philipp et al. (March 2020). "Lichens and associated fungi from Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska". The Lichenologist 52 (2): 61–181. doi:10.1017/S0024282920000079. PMID 32788812.

- Temu, Stella Gilbert; Tibell, Sanja; Tibuhwa, Donatha Damian; Tibell, Leif (October 2019). "Crustose calicioid lichens and fungi in mountain cloud forests of Tanzania". Microorganisms 7 (11): 491. doi:10.3390/microorganisms7110491. PMID 31717781. PMC 6920850. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336852414.

- "Trouble with Lichen". Penguin Books. https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/56264/trouble-with-lichen-by-wyndham-john/9780141032986.

- Truong, Camille; Clerc, Philippe (2003). "The Parmelia borreri group (lichenized ascomycetes) in Switzerland". Botanica Helvetica 113 (1): 49–61. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234167399.

- Turner, Nancy J. (October 1977). "Economic importance of black tree lichen (Bryoria fremontii) to the Indians of western North America". Economic Botany 31 (4): 461–470. doi:10.1007/BF02912559.

- Upreti, Dalip K.; Rai, Himanshu, eds (2013). Terricolous Lichens in India. 1: Diversity Patterns and Distribution Ecology. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4614-8736-4.

- Van Hoose, Natalie (21 July 2021). "Yeast emerges as hidden third partner in lichen symbiosis". Purdue University. https://www.purdue.edu/newsroom/releases/2016/Q3/yeast-emerges-as-hidden-third-partner-in-lichen-symbiosis.html.

- Vinayaka, K. S.; Krishnamurthy, Y. L. (2012). "Ethno-lichenological Studies of Shimoga and Mysore Districts, Karnataka, India". Advances in Plant Sciences 25 (1): 265–267. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286931627.

- Wijayawardene, N.N.; Hyde, K.D.; Dai, D.Q.; Sánchez-García, M.; Goto, B.T.; Saxena, R.K. et al. (2022). "Outline of Fungi and fungus-like taxa – 2021". Mycosphere 13 (1): 53–453. doi:10.5943/mycosphere/13/1/2. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358798332.

- Wilk, Karina; Pabijan, Maciej; Saługa, Marta; Gaya, Ester; Lücking, Robert (2021). "Phylogenetic revision of South American Teloschistaceae (lichenized Ascomycota, Teloschistales) reveals three new genera and species". Mycologia 113 (2): 278–299. doi:10.1080/00275514.2020.1830672. PMID 33428561.

- Zakeri, Zakieh; Junne, Stefan; Jäger, Fabian; Dostert, Marcel; Otte, Volker; Neubauer, Peter (May 2022). "Lichen cell factories: methods for the isolation of photobiont and mycobiont partners for defined pure and co-cultivation". Microbial Cell Factories 21 (1): 80. doi:10.1186/s12934-022-01804-6. PMID 35534897.

External links

- About Lichens, from the British Lichen Society

- Australian Lichens, from the Australian National Herbarium and Australian National Botanic Gardens

- Lichen Basics, from the North American Mycological Association

|

KSF

KSF