Protein primary structure

Topic: Biology

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

Protein primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids in a peptide or protein.[1] By convention, the primary structure of a protein is reported starting from the amino-terminal (N) end to the carboxyl-terminal (C) end. Protein biosynthesis is most commonly performed by ribosomes in cells. Peptides can also be synthesized in the laboratory. Protein primary structures can be directly sequenced, or inferred from DNA sequences.

Formation

Biological

Amino acids are polymerised via peptide bonds to form a long backbone, with the different amino acid side chains protruding along it. In biological systems, proteins are produced during translation by a cell's ribosomes. Some organisms can also make short peptides by non-ribosomal peptide synthesis, which often use amino acids other than the standard 20, and may be cyclised, modified and cross-linked.

Chemical

Peptides can be synthesised chemically via a range of laboratory methods. Chemical methods typically synthesise peptides in the opposite order (starting at the C-terminus) to biological protein synthesis (starting at the N-terminus).

Notation

Protein sequence is typically notated as a string of letters, listing the amino acids starting at the amino-terminal end through to the carboxyl-terminal end. Either a three letter code or single letter code can be used to represent the 20 naturally occurring amino acids, as well as mixtures or ambiguous amino acids (similar to nucleic acid notation).[1][2][3]

Peptides can be directly sequenced, or inferred from DNA sequences. Large sequence databases now exist that collate known protein sequences.

| Amino Acid | 3-Letter[4] | 1-Letter[4] |

|---|---|---|

| Alanine | Ala | A |

| Arginine | Arg | R |

| Asparagine | Asn | N |

| Aspartic acid | Asp | D |

| Cysteine | Cys | C |

| Glutamic acid | Glu | E |

| Glutamine | Gln | Q |

| Glycine | Gly | G |

| Histidine | His | H |

| Isoleucine | Ile | I |

| Leucine | Leu | L |

| Lysine | Lys | K |

| Methionine | Met | M |

| Phenylalanine | Phe | F |

| Proline | Pro | P |

| Serine | Ser | S |

| Threonine | Thr | T |

| Tryptophan | Trp | W |

| Tyrosine | Tyr | Y |

| Valine | Val | V |

| Symbol | Description | Residues represented |

|---|---|---|

| X | Any amino acid, or unknown | All |

| B | Aspartate or Asparagine | D, N |

| Z | Glutamate or Glutamine | E, Q |

| J | Leucine or Isoleucine | I, L |

| Φ | Hydrophobic | V, I, L, F, W, M |

| Ω | Aromatic | F, W, Y, H |

| Ψ | Aliphatic | V, I, L, M |

| π | Small | P, G, A, S |

| ζ | Hydrophilic | S, T, H, N, Q, E, D, K, R, Y |

| + | Positively charged | K, R, H |

| - | Negatively charged | D, E |

Modification

In general, polypeptides are unbranched polymers, so their primary structure can often be specified by the sequence of amino acids along their backbone. However, proteins can become cross-linked, most commonly by disulfide bonds, and the primary structure also requires specifying the cross-linking atoms, e.g., specifying the cysteines involved in the protein's disulfide bonds. Other crosslinks include desmosine.

Isomerisation

The chiral centers of a polypeptide chain can undergo racemization. Although it does not change the sequence, it does affect the chemical properties of the sequence. In particular, the L-amino acids normally found in proteins can spontaneously isomerize at the atom to form D-amino acids, which cannot be cleaved by most proteases. Additionally, proline can form stable trans-isomers at the peptide bond.

Post-translational modification

Additionally, the protein can undergo a variety of post-translational modifications, which are briefly summarized here.

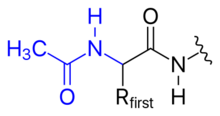

The N-terminal amino group of a polypeptide can be modified covalently, e.g.,

- acetylation

- The positive charge on the N-terminal amino group may be eliminated by changing it to an acetyl group (N-terminal blocking).

- formylation

- The N-terminal methionine usually found after translation has an N-terminus blocked with a formyl group. This formyl group (and sometimes the methionine residue itself, if followed by Gly or Ser) is removed by the enzyme deformylase.

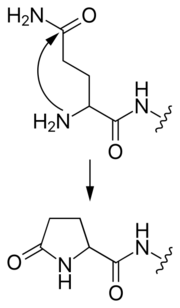

- pyroglutamate

- An N-terminal glutamine can attack itself, forming a cyclic pyroglutamate group.

- myristoylation

- Similar to acetylation. Instead of a simple methyl group, the myristoyl group has a tail of 14 hydrophobic carbons, which make it ideal for anchoring proteins to cellular membranes.

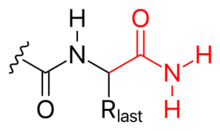

The C-terminal carboxylate group of a polypeptide can also be modified, e.g.,

- amination (see Figure)

- The C-terminus can also be blocked (thus, neutralizing its negative charge) by amination.

- glycosyl phosphatidylinositol (GPI) attachment

- Glycosyl phosphatidylinositol(GPI) is a large, hydrophobic phospholipid prosthetic group that anchors proteins to cellular membranes. It is attached to the polypeptide C-terminus through an amide linkage that then connects to ethanolamine, thence to sundry sugars and finally to the phosphatidylinositol lipid moiety.

Finally, the peptide side chains can also be modified covalently, e.g.,

- phosphorylation

- Aside from cleavage, phosphorylation is perhaps the most important chemical modification of proteins. A phosphate group can be attached to the sidechain hydroxyl group of serine, threonine and tyrosine residues, adding a negative charge at that site and producing an unnatural amino acid. Such reactions are catalyzed by kinases and the reverse reaction is catalyzed by phosphatases. The phosphorylated tyrosines are often used as "handles" by which proteins can bind to one another, whereas phosphorylation of Ser/Thr often induces conformational changes, presumably because of the introduced negative charge. The effects of phosphorylating Ser/Thr can sometimes be simulated by mutating the Ser/Thr residue to glutamate.

- A catch-all name for a set of very common and very heterogeneous chemical modifications. Sugar moieties can be attached to the sidechain hydroxyl groups of Ser/Thr or to the sidechain amide groups of Asn. Such attachments can serve many functions, ranging from increasing solubility to complex recognition. All glycosylation can be blocked with certain inhibitors, such as tunicamycin.

- deamidation (succinimide formation)

- In this modification, an asparagine or aspartate side chain attacks the following peptide bond, forming a symmetrical succinimide intermediate. Hydrolysis of the intermediate produces either aspartate or the β-amino acid, iso(Asp). For asparagine, either product results in the loss of the amide group, hence "deamidation".

- Proline residues may be hydroxylated at either of two atoms, as can lysine (at one atom). Hydroxyproline is a critical component of collagen, which becomes unstable upon its loss. The hydroxylation reaction is catalyzed by an enzyme that requires ascorbic acid (vitamin C), deficiencies in which lead to many connective-tissue diseases such as scurvy.

- Several protein residues can be methylated, most notably the positive groups of lysine and arginine. Arginine residues interact with the nucleic acid phosphate backbone and commonly form hydrogen bonds with the base residues, particularly guanine, in protein–DNA complexes. Lysine residues can be singly, doubly and even triply methylated. Methylation does not alter the positive charge on the side chain, however.

- Acetylation of the lysine amino groups is chemically analogous to the acetylation of the N-terminus. Functionally, however, the acetylation of lysine residues is used to regulate the binding of proteins to nucleic acids. The cancellation of the positive charge on the lysine weakens the electrostatic attraction for the (negatively charged) nucleic acids.

- sulfation

- Tyrosines may become sulfated on their atom. Somewhat unusually, this modification occurs in the Golgi apparatus, not in the endoplasmic reticulum. Similar to phosphorylated tyrosines, sulfated tyrosines are used for specific recognition, e.g., in chemokine receptors on the cell surface. As with phosphorylation, sulfation adds a negative charge to a previously neutral site.

- prenylation and palmitoylation

- The hydrophobic isoprene (e.g., farnesyl, geranyl, and geranylgeranyl groups) and palmitoyl groups may be added to the atom of cysteine residues to anchor proteins to cellular membranes. Unlike the GPI and myritoyl anchors, these groups are not necessarily added at the termini.

- carboxylation

- A relatively rare modification that adds an extra carboxylate group (and, hence, a double negative charge) to a glutamate side chain, producing a Gla residue. This is used to strengthen the binding to "hard" metal ions such as calcium.

- ADP-ribosylation

- The large ADP-ribosyl group can be transferred to several types of side chains within proteins, with heterogeneous effects. This modification is a target for the powerful toxins of disparate bacteria, e.g., Vibrio cholerae, Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Bordetella pertussis.

- Various full-length, folded proteins can be attached at their C-termini to the sidechain ammonium groups of lysines of other proteins. Ubiquitin is the most common of these, and usually signals that the ubiquitin-tagged protein should be degraded.

Most of the polypeptide modifications listed above occur post-translationally, i.e., after the protein has been synthesized on the ribosome, typically occurring in the endoplasmic reticulum, a subcellular organelle of the eukaryotic cell.

Many other chemical reactions (e.g., cyanylation) have been applied to proteins by chemists, although they are not found in biological systems.

Cleavage and ligation

In addition to those listed above, the most important modification of primary structure is peptide cleavage (by chemical hydrolysis or by proteases). Proteins are often synthesized in an inactive precursor form; typically, an N-terminal or C-terminal segment blocks the active site of the protein, inhibiting its function. The protein is activated by cleaving off the inhibitory peptide.

Some proteins even have the power to cleave themselves. Typically, the hydroxyl group of a serine (rarely, threonine) or the thiol group of a cysteine residue will attack the carbonyl carbon of the preceding peptide bond, forming a tetrahedrally bonded intermediate [classified as a hydroxyoxazolidine (Ser/Thr) or hydroxythiazolidine (Cys) intermediate]. This intermediate tends to revert to the amide form, expelling the attacking group, since the amide form is usually favored by free energy, (presumably due to the strong resonance stabilization of the peptide group). However, additional molecular interactions may render the amide form less stable; the amino group is expelled instead, resulting in an ester (Ser/Thr) or thioester (Cys) bond in place of the peptide bond. This chemical reaction is called an N-O acyl shift.

The ester/thioester bond can be resolved in several ways:

- Simple hydrolysis will split the polypeptide chain, where the displaced amino group becomes the new N-terminus. This is seen in the maturation of glycosylasparaginase.

- A β-elimination reaction also splits the chain, but results in a pyruvoyl group at the new N-terminus. This pyruvoyl group may be used as a covalently attached catalytic cofactor in some enzymes, especially decarboxylases such as S-adenosylmethionine decarboxylase (SAMDC) that exploit the electron-withdrawing power of the pyruvoyl group.

- Intramolecular transesterification, resulting in a branched polypeptide. In inteins, the new ester bond is broken by an intramolecular attack by the soon-to-be C-terminal asparagine.

- Intermolecular transesterification can transfer a whole segment from one polypeptide to another, as is seen in the Hedgehog protein autoprocessing.

Sequence compression

The compression of amino acid sequences is a comparatively challenging task. The existing specialized amino acid sequence compressors are low compared with that of DNA sequence compressors, mainly because of the characteristics of the data. For example, modeling inversions is harder because of the reverse information loss (from amino acids to DNA sequence). The current lossless data compressor that provides higher compression is AC2.[5] AC2 mixes various context models using Neural Networks and encodes the data using arithmetic encoding.

History

The proposal that proteins were linear chains of α-amino acids was made nearly simultaneously by two scientists at the same conference in 1902, the 74th meeting of the Society of German Scientists and Physicians, held in Karlsbad. Franz Hofmeister made the proposal in the morning, based on his observations of the biuret reaction in proteins. Hofmeister was followed a few hours later by Emil Fischer, who had amassed a wealth of chemical details supporting the peptide-bond model. For completeness, the proposal that proteins contained amide linkages was made as early as 1882 by the French chemist E. Grimaux.[6]

Despite these data and later evidence that proteolytically digested proteins yielded only oligopeptides, the idea that proteins were linear, unbranched polymers of amino acids was not accepted immediately. Some well-respected scientists such as William Astbury doubted that covalent bonds were strong enough to hold such long molecules together; they feared that thermal agitations would shake such long molecules asunder. Hermann Staudinger faced similar prejudices in the 1920s when he argued that rubber was composed of macromolecules.[6]

Thus, several alternative hypotheses arose. The colloidal protein hypothesis stated that proteins were colloidal assemblies of smaller molecules. This hypothesis was disproved in the 1920s by ultracentrifugation measurements by Theodor Svedberg that showed that proteins had a well-defined, reproducible molecular weight and by electrophoretic measurements by Arne Tiselius that indicated that proteins were single molecules. A second hypothesis, the cyclol hypothesis advanced by Dorothy Wrinch, proposed that the linear polypeptide underwent a chemical cyclol rearrangement C=O + HN C(OH)-N that crosslinked its backbone amide groups, forming a two-dimensional fabric. Other primary structures of proteins were proposed by various researchers, such as the diketopiperazine model of Emil Abderhalden and the pyrrol/piperidine model of Troensegaard in 1942. Although never given much credence, these alternative models were finally disproved when Frederick Sanger successfully sequenced insulin[when?] and by the crystallographic determination of myoglobin and hemoglobin by Max Perutz and John Kendrew[when?].

Primary structure in other molecules

Any linear-chain heteropolymer can be said to have a "primary structure" by analogy to the usage of the term for proteins, but this usage is rare compared to the extremely common usage in reference to proteins. In RNA, which also has extensive secondary structure, the linear chain of bases is generally just referred to as the "sequence" as it is in DNA (which usually forms a linear double helix with little secondary structure). Other biological polymers such as polysaccharides can also be considered to have a primary structure, although the usage is not standard.

Relation to secondary and tertiary structure

The primary structure of a biological polymer to a large extent determines the three-dimensional shape (tertiary structure). Protein sequence can be used to predict local features, such as segments of secondary structure, or trans-membrane regions. However, the complexity of protein folding currently prohibits predicting the tertiary structure of a protein from its sequence alone. Knowing the structure of a similar homologous sequence (for example a member of the same protein family) allows highly accurate prediction of the tertiary structure by homology modeling. If the full-length protein sequence is available, it is possible to estimate its general biophysical properties, such as its isoelectric point.

Sequence families are often determined by sequence clustering, and structural genomics projects aim to produce a set of representative structures to cover the sequence space of possible non-redundant sequences.

See also

- Protein sequencing

- Nucleic acid primary structure

- Translation

- Pseudo amino acid composition

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 SANGER F (1952). "The arrangement of amino acids in proteins". in M.L. Anson. Advances in Protein Chemistry. 7. pp. 1–67. doi:10.1016/S0065-3233(08)60017-0. ISBN 9780120342075.

- ↑ Aasland, Rein; Abrams, Charles; Ampe, Christophe; Ball, Linda J.; Bedford, Mark T.; Cesareni, Gianni; Gimona, Mario; Hurley, James H. et al. (2002-02-20). "Normalization of nomenclature for peptide motifs as ligands of modular protein domains". FEBS Letters 513 (1): 141–144. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(01)03295-1. ISSN 1873-3468. PMID 11911894.

- ↑ "A One-Letter Notation for Amino Acid Sequences*". European Journal of Biochemistry 5 (2): 151–153. 1968-07-01. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1968.tb00350.x. ISSN 1432-1033. PMID 11911894.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hausman, Robert E.; Cooper, Geoffrey M. (2004). The cell: a molecular approach. Washington, D.C: ASM Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-87893-214-6.

- ↑ Silva M, Pratas D, Pinho AJ (April 2021). "AC2: An Efficient Protein Sequence Compression Tool Using Artificial Neural Networks and Cache-Hash Models". Entropy 23 (5): 530. doi:10.3390/e23050530. PMID 33925812. Bibcode: 2021Entrp..23..530S.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Fruton JS (May 1979). "Early theories of protein structure". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 325 (1): xiv, 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1979.tb14125.x. PMID 378063. Bibcode: 1979NYASA.325....1F.

|

KSF

KSF