Test

Topic: Biology

From HandWiki - Reading time: 3 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 3 min

In biology, a test is the hard shell of some spherical marine animals and protists, notably sea urchins and microorganisms such as testate foraminiferans, radiolarians, and testate amoebae. The term is also applied to the covering of scale insects. The related Latin term testa is used for the hard seed coat of plant seeds.

Etymology

The anatomical term "test" derives from the Latin testa (which means a rounded bowl, amphora or bottle).

Structure

The test is a skeletal structure, made of hard material such as calcium carbonate, silica, chitin or composite materials. As such, it allows the protection of the internal organs and the attachment of soft flesh.

In sea urchins

The test of sea urchins is made of calcium carbonate, strengthened by a framework of calcite monocrystals, in a characteristic "stereomic" structure. These two ingredients provide sea urchins with a great solidity and a moderate weight, as well as the capacity to regenerate the mesh from the cuticle. According to a 2012 study,[1] the skeletal structures of sea urchins consist of 92% of "bricks" of calcite monocrystals (conferring solidity and hardness) and 8% of a "mortar" of amorphous lime (allowing flexibility and lightness). This lime is constituted itself of 99.9% of calcium carbonate, with 0.1% structural proteins, which make sea urchins animals with an extremely mineralized skeleton (which also explains their excellent conservation as fossils).[1]

In foraminiferans

The test of foraminifera, a group of single-celled organisms, is extremely evolutionarily diverse. Many different methods of constructing the test are present, from lacking a test in Reticulomyxa, proteinaceous tests in the "allogromiids", agglomerated tests made from foreign particles in many groups including textulariids, silica tests in silicoloculinids, and aragonite or calcite tests in many forms including miliolids and rotaliids. It can be of many types, including proteinaceous, agglutinated (exogenous agglomerate), porcelain-like (smooth calcite) or hyalin (lens). Foraminifera with multi-chambered tests are referred to as multilocular and develop by building new chambers in their test. These are arranged according to a geometry particular to each species: they can be rectilinear, curved, rolled up or cyclic, uniserial or multiserial. These organizational types can also be mixed, or even more complex. Miliolids have a particular arrangement of chambers known as "milioline". The surface of the test can be smooth or textured, and may be perforated with small holes.[2]

In ascidians

In ascidians the sheath is sometimes called test as well, and is composed largely of a particular type of cellulose historically termed "tunicine". From 1845 (when this was discovered by Schmidt) until 1958 (when cellulose fibres were found in mammalian connective tissue), ascidians were believed to be the only animals that synthesised cellulose.[3]

Other terms

On a strictly scientific point of view, the term "test" should be restricted to the hard shell protecting sea urchins and foraminiferans. For sessile echinoderms (like crinoids, but also many fossile groups such as cistoids or blastoids), the correct word is "theca". For diatomea, the term in use is "frustule", and for radiolarians it should be "capsule". The more common word "shell" is used for mollusks, arthropods and turtles (even if the latter ones belong to the order "Testudines").

-

Sea urchin tests (Coelopleurus exquisitus on a Phyllacanthus imperialis).

-

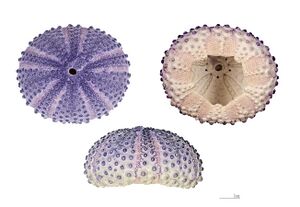

Test of a purple sea urchin.

-

Test of an irregular sea urchin (Echinocardium).

-

Foraminiferans' tests from the Adriatic Sea.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 J. Seto; Y. Ma; S. Davis; F. Meldrum; A. Gourrier; Y.Y. Kime; U. Schilde; M. Sztucki et al. (2012). "Structure-property relationships of a biological mesocrystal in the adult sea urchin spine". PNAS 109 (18): 3699–4304. doi:10.1073/pnas.1204261109. PMID 22343283.

- ↑ Saraswati, Pratul Kumar; Srinivasan, M. S. (2016), "Calcareous-Walled Microfossils" (in en), Micropaleontology (Cham: Springer International Publishing): pp. 81–119, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-14574-7_6, ISBN 978-3-319-14573-0, http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-14574-7_6, retrieved 2020-09-12

- ↑ Endean, The Test of the Ascidian, Phallusia mammillata, Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, Vol. 102, part 1, pp. 107-117, 1961.

See also

- Frustule

- Lorica (biology)

KSF

KSF