Allenes

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 16 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 16 min

In organic chemistry, allenes are organic compounds in which one carbon atom has double bonds with each of its two adjacent carbon atoms (R

2C=C=CR

2, where R is H or some organyl group).[1] Allenes are classified as cumulated dienes. The parent compound of this class is propadiene (H

2C=C=CH

2), which is itself also called allene. An group of the structure R

2C=C=CR– is called allenyl, where R is H or some alkyl group. Compounds with an allene-type structure but with more than three carbon atoms are members of a larger class of compounds called cumulenes with X=C=Y bonding.

History

For many years, allenes were viewed as curiosities but thought to be synthetically useless and difficult to prepare and to work with.[2][3] Reportedly,[4] the first synthesis of an allene, glutinic acid, was performed in an attempt to prove the non-existence of this class of compounds.[5][6] The situation began to change in the 1950s, and more than 300 papers on allenes have been published in 2012 alone.[7] These compounds are not just interesting intermediates but synthetically valuable targets themselves; for example, over 150 natural products are known with an allene or cumulene fragment.[4]

Structure and properties

Geometry

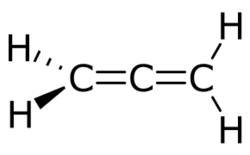

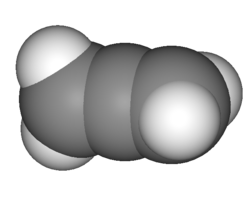

The central carbon atom of allenes forms two sigma bonds and two pi bonds. The central carbon atom is sp-hybridized, and the two terminal carbon atoms are sp2-hybridized. The bond angle formed by the three carbon atoms is 180°, indicating linear geometry for the central carbon atom. The two terminal carbon atoms are planar, and these planes are twisted 90° from each other. The structure can also be viewed as an "extended tetrahedral" with a similar shape to methane, an analogy that is continued into the stereochemical analysis of certain derivative molecules.

Symmetry

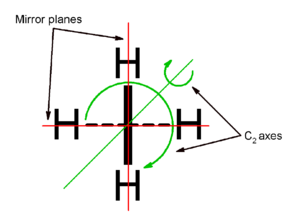

The symmetry and isomerism of allenes has long fascinated organic chemists.[8] For allenes with four identical substituents, there exist two twofold axes of rotation through the central carbon atom, inclined at 45° to the CH2 planes at either end of the molecule. The molecule can thus be thought of as a two-bladed propeller. A third twofold axis of rotation passes through the C=C=C bonds, and there is a mirror plane passing through both CH2 planes. Thus this class of molecules belong to the D2d point group. Because of the symmetry, an unsubstituted allene has no net dipole moment, that is, it is a non-polar molecule.

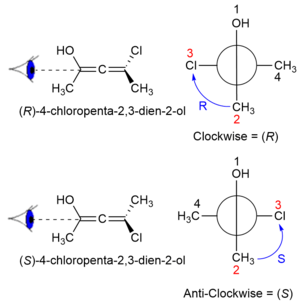

An allene with two different substituents on each of the two carbon atoms will be chiral because there will no longer be any mirror planes. The chirality of these types of allenes was first predicted in 1875 by Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff, but not proven experimentally until 1935.[9] Where A has a greater priority than B according to the Cahn–Ingold–Prelog priority rules, the configuration of the axial chirality can be determined by considering the substituents on the front atom followed by the back atom when viewed along the allene axis. For the back atom, only the group of higher priority need be considered.

Chiral allenes have been recently used as building blocks in the construction of organic materials with exceptional chiroptical properties.[10] There are a few examples of drug molecule having an allene system in their structure.[11] Mycomycin, an antibiotic with tuberculostatic properties,[12] is a typical example. This drug exhibits enantiomerism due to the presence of a suitably substituted allene system.

Although the semi-localized textbook σ-π separation model describes the bonding of allene using a pair of localized orthogonal π orbitals, the full molecular orbital description of the bonding is more subtle. The symmetry-correct doubly-degenerate HOMOs of allene (adapted to the D2d point group) can either be represented by a pair of orthogonal MOs or as twisted helical linear combinations of these orthogonal MOs. The symmetry of the system and the degeneracy of these orbitals imply that both descriptions are correct (in the same way that there are infinitely many ways to depict the doubly-degenerate HOMOs and LUMOs of benzene that correspond to different choices of eigenfunctions in a two-dimensional eigenspace). However, this degeneracy is lifted in substituted allenes, and the helical picture becomes the only symmetry-correct description for the HOMO and HOMO–1 of the C2-symmetric 1,3-dimethylallene.[13][14] This qualitative MO description extends to higher odd-carbon cumulenes (e.g., 1,2,3,4-pentatetraene).

Chemical and spectral properties

Allenes differ considerably from other alkenes in terms of their chemical properties. Compared to isolated and conjugated dienes, they are considerably less stable: comparing the isomeric pentadienes, the allenic 1,2-pentadiene has a heat of formation of 33.6 kcal/mol, compared to 18.1 kcal/mol for (E)-1,3-pentadiene and 25.4 kcal/mol for the isolated 1,4-pentadiene.[15]

The C–H bonds of allenes are considerably weaker and more acidic compared to typical vinylic C–H bonds: the bond dissociation energy is 87.7 kcal/mol (compared to 111 kcal/mol in ethylene), while the gas-phase acidity is 381 kcal/mol (compared to 409 kcal/mol for ethylene[16]), making it slightly more acidic than the propargylic C–H bond of propyne (382 kcal/mol).

The 13C NMR spectrum of allenes is characterized by the signal of the sp-hybridized carbon atom, resonating at a characteristic 200-220 ppm. In contrast, the sp2-hybridized carbon atoms resonate around 80 ppm in a region typical for alkyne and nitrile carbon atoms, while the protons of a CH2 group of a terminal allene resonate at around 4.5 ppm — somewhat upfield of a typical vinylic proton.[17]

Allenes possess a rich cycloaddition chemistry, including both [4+2] and [2+2] modes of addition,[18][19] as well as undergoing formal cycloaddition processes catalyzed by transition metals.[20][21] Allenes also serve as substrates for transition metal catalyzed hydrofunctionalization reactions.[22][23][24]

Synthesis

Although allenes often require specialized syntheses, the parent allene, propadiene is produced industrially on a large scale as an equilibrium mixture with methylacetylene:

This mixture, known as MAPP gas, is commercially available. At 298 K, the ΔG° of this reaction is –1.9 kcal/mol, corresponding to Keq = 24.7.[25]

The first allene to be synthesized was penta-2,3-dienedioic acid, which was prepared by Burton and Pechmann in 1887. However, the structure was only correctly identified in 1954.[26]

Laboratory methods for the formation of allenes include:

- from geminal dihalocyclopropanes and organolithium compounds (or metallic sodium or magnesium) in the Skattebøl rearrangement (Doering–LaFlamme allene synthesis) via rearrangement of cyclopropylidene carbenes/carbenoids

- from reaction of certain terminal alkynes with formaldehyde, copper(I) bromide, and added base (Crabbé–Ma allene synthesis)[27][28]

- from propargylic halides by SN2′ displacement by an organocuprate[29]

- from dehydrohalogenation of certain dihalides[30]

- from reaction of a triphenylphosphinyl ester with an acid halide, a Wittig reaction accompanied by dehydrohalogenation[31][32]

- from propargylic alcohols via the Myers allene synthesis protocol—a stereospecific process

- from metalation of allene or substituted allenes with BuLi and reaction with electrophiles (RX, R3SiX, D2O, etc.)[33]

The chemistry of allenes has been reviewed in a number of books[2][34][35][36] and journal articles.[3][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44] Some key approaches towards allenes are outlined in the following scheme:[45][46][47][48]

One of the older methods is the Skattebøl rearrangement[45][49][50] (also called the Doering–Moore–Skattebøl or Doering–LaFlamme[51][52] rearrangement), in which a gem-dihalocyclopropane 3 is treated with an organolithium compound (or dissolving metal) and the presumed intermediate rearranges into an allene either directly or via carbene-like species. Notably, even strained allenes can be generated by this procedure.[53] Modifications involving leaving groups of different nature are also known.[45] Arguably, the most convenient modern method of allene synthesis is by sigmatropic rearrangement of propargylic substrates.[46][47][48] Johnson–Claisen[48] and Ireland–Claisen[54] rearrangements of ketene acetals 4 have been used a number of times to prepare allenic esters and acids. Reactions of vinyl ethers 5 (the Saucy–Marbet rearrangement) give allene aldehydes,[55] while propargylic sulfenates 6 give allene sulfoxides.[56][57] Allenes can also be prepared by nucleophilic substitution in 9 and 10 (nucleophile Nu− can be a hydride anion), 1,2-elimination from 8, proton transfer in 7, and other, less general, methods.[46][47]

Use and occurrence

The dominant use of allenes is allene itself, which, in equilibrium with propyne is a component of MAP gas.[58]

Research

The reactivity of substituted allenes has been well explored.[59][60][61][62]

The two π-bonds are located at the 90° angle to each other, and thus require a reagent to approach from somewhat different directions. With an appropriate substitution pattern, allenes exhibit axial chirality as predicted by van’t Hoff as early as 1875.[63][62] Protonation of allenes gives cations 11 that undergo further transformations.[64] Reactions with soft electrophiles (e.g. Br+) deliver positively charged onium ions 13.[65] Transition-metal-catalysed reactions proceed via allylic intermediates 15 and have attracted significant interest in recent years.[66][67] Numerous cycloadditions are also known, including [4+2]-, (2+1)-, and [2+2]-variants, which deliver, e.g., 12, 14, and 16, respectively.[59][68][69][70]

Occurrence

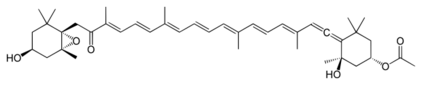

Numerous natural products contain the allene functional group. Noteworthy are the pigments fucoxanthin and peridinin. Little is known about the biosynthesis, although it is conjectured that they are often generated from alkyne precursors.[71]

Allenes serve as ligands in organometallic chemistry. A typical complex is Pt(η2-allene)(PPh3)2. Ni(0) reagents catalyze the cyclooligomerization of allene.[72] Using a suitable catalyst (e.g. Wilkinson's catalyst), it is possible to reduce just one of the double bonds of an allene.[73]

Delta convention

Many rings or ring systems are known by semisystematic names that assume a maximum number of noncumulative bonds. To unambiguously specify derivatives that include cumulated bonds (and hence fewer hydrogen atoms than would be expected from the skeleton), a lowercase delta may be used with a subscript indicating the number of cumulated double bonds from that atom, e.g. 8δ2-benzocyclononene. This may be combined with the λ-convention for specifying nonstandard valency states, e.g. 2λ4δ2,5λ4δ2-thieno[3,4-c]thiophene.[74]

See also

- Compounds with three or more adjacent carbon–carbon double bonds are called cumulenes.

References

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "allenes". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00238

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 The Chemistry of the Allenes (vol. 1−3); Landor, S. R., Ed.; cademic Press: London, 1982.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Taylor, David R. (1967-06-01). "The Chemistry of Allenes" (in en). Chemical Reviews 67 (3): 317–359. doi:10.1021/cr60247a004. ISSN 0009-2665. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/cr60247a004.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hoffmann-Röder, Anja; Krause, Norbert (2004-02-27). "Synthesis and Properties of Allenic Natural Products and Pharmaceuticals" (in en). Angewandte Chemie International Edition 43 (10): 1196–1216. doi:10.1002/anie.200300628. ISSN 1433-7851. PMID 14991780. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.200300628.

- ↑ Burton, B. S.; von Pechmann, H. (January 1887). "Ueber die Einwirkung von Chlorphosphor auf Acetondicarbonsäureäther" (in de). Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft 20 (1): 145–149. doi:10.1002/cber.18870200136. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cber.18870200136.

- ↑ Jones, E. R. H.; Mansfield, G. H.; Whiting, M. C. (1954). "Researches on acetylenic compounds. Part XLVII. The prototropic rearrangements of some acetylenic dicarboxylic acids" (in en). Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 3208–3212. doi:10.1039/jr9540003208. ISSN 0368-1769. http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=jr9540003208.

- ↑ Data from the Web of Science database.

- ↑ Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1, https://books.google.com/books?id=JDR-nZpojeEC&printsec=frontcover

- ↑ Maitland, Peter; Mills, W. H. (1935). "Experimental Demonstration of the Allene Asymmetry". Nature 135 (3424): 994. doi:10.1038/135994a0. Bibcode: 1935Natur.135Q.994M.

- ↑ Rivera Fuentes, Pablo; Diederich, François (2012). "Allenes in Molecular Materials". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51 (12): 2818–2828. doi:10.1002/anie.201108001. PMID 22308109.

- ↑ Celmer, Walter D.; Solomons, I. A. (1952). "The Structure of the Antibiotic Mycomycin". Journal of the American Chemical Society 74 (7): 1870–1871. doi:10.1021/ja01127a529. ISSN 0002-7863. http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja01127a529.

- ↑ JENKINS, D E (1950). "Mycomycin: a new antibiotic with tuberculostatic properties.". J Lab Clin Med 36 (5): 841–2. PMID 14784717.

- ↑ H. Hendon, Christopher; Tiana, Davide; T. Murray, Alexander; R. Carbery, David; Walsh, Aron (2013). "Helical frontier orbitals of conjugated linear molecules" (in en). Chemical Science 4 (11): 4278–4284. doi:10.1039/C3SC52061G.

- ↑ Garner, Marc H.; Hoffmann, Roald; Rettrup, Sten; Solomon, Gemma C. (2018-06-27). "Coarctate and Möbius: The Helical Orbitals of Allene and Other Cumulenes". ACS Central Science 4 (6): 688–700. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.8b00086. ISSN 2374-7943. PMID 29974064.

- ↑ Informatics, NIST Office of Data and (1997) (in en). Welcome to the NIST WebBook. doi:10.18434/T4D303. https://webbook.nist.gov/index.html.en-us.en. Retrieved 2020-10-17.

- ↑ Alabugin, Igor V. (2016-09-19) (in en). Stereoelectronic Effects: A Bridge Between Structure and Reactivity. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. doi:10.1002/9781118906378. ISBN 978-1-118-90637-8. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/9781118906378.

- ↑ Pretsch, Ernö, 1942- (2009). Structure determination of organic compounds : tables of spectral data. Bühlmann, P. (Philippe), 1964-, Badertscher, M. (Fourth, Revised and Enlarged ed.). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-93810-1. OCLC 405547697. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/405547697.

- ↑ Alcaide, Benito; Almendros, Pedro; Aragoncillo, Cristina (2010-01-28). "Exploiting [2+2 cycloaddition chemistry: achievements with allenes"] (in en). Chemical Society Reviews 39 (2): 783–816. doi:10.1039/B913749A. ISSN 1460-4744. PMID 20111793. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2010/cs/b913749a.

- ↑ Pasto, Daniel J. (January 1984). "Recent developments in allene chemistry" (in en). Tetrahedron 40 (15): 2805–2827. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91289-X. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S004040200191289X.

- ↑ Alcaide, Benito; Almendros, Pedro (August 2004). "The Allenic Pauson−Khand Reaction in Synthesis" (in en). European Journal of Organic Chemistry 2004 (16): 3377–3383. doi:10.1002/ejoc.200400023. ISSN 1434-193X. http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ejoc.200400023.

- ↑ Mascareñas, José L.; Varela, Iván; López, Fernando (2019-02-19). "Allenes and Derivatives in Gold(I)- and Platinum(II)-Catalyzed Formal Cycloadditions" (in en). Accounts of Chemical Research 52 (2): 465–479. doi:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00567. ISSN 0001-4842. PMID 30640446.

- ↑ Zi, Weiwei; Toste, F. Dean (2016-08-08). "Recent advances in enantioselective gold catalysis" (in en). Chemical Society Reviews 45 (16): 4567–4589. doi:10.1039/C5CS00929D. ISSN 1460-4744. PMID 26890605. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2016/cs/c5cs00929d.

- ↑ Lee, Mitchell; Nguyen, Mary; Brandt, Chance; Kaminsky, Werner; Lalic, Gojko (2017-12-04). "Catalytic Hydroalkylation of Allenes" (in en). Angewandte Chemie International Edition 56 (49): 15703–15707. doi:10.1002/anie.201709144. PMID 29052303.

- ↑ Kim, Seung Wook; Meyer, Cole C.; Mai, Binh Khanh; Liu, Peng; Krische, Michael J. (2019-10-04). "Inversion of Enantioselectivity in Allene Gas versus Allyl Acetate Reductive Aldehyde Allylation Guided by Metal-Centered Stereogenicity: An Experimental and Computational Study". ACS Catalysis 9 (10): 9158–9163. doi:10.1021/acscatal.9b03695. PMID 31857913.

- ↑ Robinson, Marin S.; Polak, Mark L.; Bierbaum, Veronica M.; DePuy, Charles H.; Lineberger, W. C. (1995-06-01). "Experimental Studies of Allene, Methylacetylene, and the Propargyl Radical: Bond Dissociation Energies, Gas-Phase Acidities, and Ion-Molecule Chemistry". Journal of the American Chemical Society 117 (25): 6766–6778. doi:10.1021/ja00130a017. ISSN 0002-7863. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00130a017.

- ↑ Jones, E. R. H.; Mansfield, G. H.; Whiting, M. C. (1954-01-01). "Researches on acetylenic compounds. Part XLVII. The prototropic rearrangements of some acetylenic dicarboxylic acids" (in en). Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 3208–3212. doi:10.1039/JR9540003208. ISSN 0368-1769. https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/1954/jr/jr9540003208.

- ↑ Crabbé, Pierre; Nassim, Bahman; Robert-Lopes, Maria-Teresa. "One-Step Homologation of Acetylenes to Allenes: 4-Hydroxynona-1,2-diene [1,2-Nonadien-4-ol"]. Organic Syntheses 63: 203. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.063.0203. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=CV7P0276.; Collective Volume, 7, pp. 276

- ↑ Luo, Hongwen; Ma, Dengke; Ma, Shengming (2017). "Buta-2,3-dien-1-ol". Organic Syntheses: 153–166. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.094.0153. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=v94p0153.

- ↑ Yoshikai, Naohiko; Nakamura, Eiichi (2012-04-11). "Mechanisms of Nucleophilic Organocopper(I) Reactions" (in en). Chemical Reviews 112 (4): 2339–2372. doi:10.1021/cr200241f. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 22111574. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cr200241f.

- ↑ Cripps, H. N.; Kiefer, E. F.. "Allene". Organic Syntheses 42: 12. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.042.0012. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=CV5P0022.; Collective Volume, 5, pp. 22

- ↑ Lang, Robert W.; Hansen, Hans-Jürgen (1980). "Eine einfache Allencarbonsäureester-Synthese mittels der Wittig-Reaktion". Helv. Chim. Acta 63 (2): 438–455. doi:10.1002/hlca.19800630215.

- ↑ Lang, Robert W.; Hansen, Hans-Jürgen. "α-Allenic Esters from α-Phosphoranylidene Esters and Acid Chlorides: Ethyl 2,3-Pentadienoate [2,3-Pentadienoic acid, ethyl ester"]. Organic Syntheses 62: 202. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.062.0202. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=CV7P0232.; Collective Volume, 7, pp. 232

- ↑ Michelot, Didier; Clinet, Jean-Claude; Linstrumelle, Gérard (1982-01-01). "Allenyllithium Reagents (VI)1. A Highly Regioselective Metalation of Allenic Hydrocarbons2. A Route to Mono, DI, TRI or Tetrasubstituted Allenes". Synthetic Communications 12 (10): 739–747. doi:10.1080/00397918208061912. ISSN 0039-7911. https://doi.org/10.1080/00397918208061912.

- ↑ The chemistry of ketenes, allenes and related compounds. Part 1. Saul Patai. Chichester: Wiley. 1980. ISBN 978-0-470-77160-0. OCLC 501315951. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/501315951.

- ↑ The chemistry of ketenes, allenes and related compounds. Part 2. Saul Patai. Chichester: Wiley. 1980. ISBN 978-0-470-77161-7. OCLC 520990503. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/520990503.

- ↑ Brandsma, L. (2004). Synthesis of acetylenes, allenes and cumulenes : methods and techniques. H. D. Verkruijsse (1st ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-125751-4. OCLC 162570992. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/162570992.

- ↑ Pasto, Daniel J. (January 1984). "Recent developments in allene chemistry" (in en). Tetrahedron 40 (15): 2805–2827. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91289-X. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S004040200191289X.

- ↑ Zimmer, Reinhold; Dinesh, Chimmanamada U.; Nandanan, Erathodiyil; Khan, Faiz Ahmed (2000-08-01). "Palladium-Catalyzed Reactions of Allenes" (in en). Chemical Reviews 100 (8): 3067–3126. doi:10.1021/cr9902796. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 11749314. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cr9902796.

- ↑ Ma, Shengming (2009-10-20). "Electrophilic Addition and Cyclization Reactions of Allenes" (in en). Accounts of Chemical Research 42 (10): 1679–1688. doi:10.1021/ar900153r. ISSN 0001-4842. PMID 19603781. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ar900153r.

- ↑ Alcaide, Benito; Almendros, Pedro; Aragoncillo, Cristina (2010). "Exploiting [2+2 cycloaddition chemistry: achievements with allenes"] (in en). Chem. Soc. Rev. 39 (2): 783–816. doi:10.1039/B913749A. ISSN 0306-0012. PMID 20111793. http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=B913749A.

- ↑ Pinho e Melo, Teresa M. V. D. (July 2011). "Allenes as building blocks in heterocyclic chemistry" (in en). Monatshefte für Chemie - Chemical Monthly 142 (7): 681–697. doi:10.1007/s00706-011-0505-7. ISSN 0026-9247. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00706-011-0505-7.

- ↑ López, Fernando; Mascareñas, José Luis (2011-01-10). "Allenes as Three-Carbon Units in Catalytic Cycloadditions: New Opportunities with Transition-Metal Catalysts" (in en). Chemistry – A European Journal 17 (2): 418–428. doi:10.1002/chem.201002366. ISSN 0947-6539. PMID 21207554. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/chem.201002366.

- ↑ Aubert, Corinne; Fensterbank, Louis; Garcia, Pierre; Malacria, Max; Simonneau, Antoine (2011-03-09). "Transition Metal Catalyzed Cycloisomerizations of 1, n -Allenynes and -Allenenes" (in en). Chemical Reviews 111 (3): 1954–1993. doi:10.1021/cr100376w. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 21391568. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cr100376w.

- ↑ Krause, Norbert; Winter, Christian (2011-03-09). "Gold-Catalyzed Nucleophilic Cyclization of Functionalized Allenes: A Powerful Access to Carbo- and Heterocycles" (in en). Chemical Reviews 111 (3): 1994–2009. doi:10.1021/cr1004088. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 21314182. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cr1004088.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Sydnes, Leiv K. (2003-04-01). "Allenes from Cyclopropanes and Their Use in Organic SynthesisRecent Developments" (in en). Chemical Reviews 103 (4): 1133–1150. doi:10.1021/cr010025w. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 12683779. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cr010025w.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 Brummond, Kay; DeForrest, Jolie (March 2007). "Synthesizing Allenes Today (1982-2006)" (in en). Synthesis 2007 (6): 795–818. doi:10.1055/s-2007-965963. ISSN 0039-7881. http://www.thieme-connect.de/DOI/DOI?10.1055/s-2007-965963.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Yu, Shichao; Ma, Shengming (2011). "How easy are the syntheses of allenes?" (in en). Chemical Communications 47 (19): 5384–5418. doi:10.1039/C0CC05640E. ISSN 1359-7345. PMID 21409186. http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=C0CC05640E.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Tejedor, David; Méndez-Abt, Gabriela; Cotos, Leandro; García-Tellado, Fernando (2013). "Propargyl Claisen rearrangement: allene synthesis and beyond" (in en). Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (2): 458–471. doi:10.1039/C2CS35311C. ISSN 0306-0012. PMID 23034723. http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=C2CS35311C.

- ↑ Skattebøl, Lars; Nilsson, Martin; Lindberg, Bengt; McKay, James; Munch-Petersen, Jon (1963). "The Synthesis of Allenes from 1,1-Dihalocyclopropane Derivatives and Alkyllithium." (in en). Acta Chemica Scandinavica 17: 1683–1693. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.17-1683. ISSN 0904-213X.

- ↑ Moore, William R.; Ward, Harold R. (December 1962). "The Formation of Allenes from gem-Dihalocyclopropanes by Reaction with Alkyllithium Reagents 1,2" (in en). The Journal of Organic Chemistry 27 (12): 4179–4181. doi:10.1021/jo01059a013. ISSN 0022-3263. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jo01059a013.

- ↑ Fedoryński, Michał (2003-04-01). "Syntheses of gem -Dihalocyclopropanes and Their Use in Organic Synthesis" (in en). Chemical Reviews 103 (4): 1099–1132. doi:10.1021/cr0100087. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 12683778. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cr0100087.

- ↑ Kurti, Laszlo (2005). Strategic Applications of Named Reactions in Organic Synthesis : Background and Detailed Mechanisms.. Barbara Czako. Burlington: Elsevier Science. pp. 758. ISBN 978-0-08-057541-4. OCLC 850164343. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/850164343.

- ↑ Shi, Min; Shao, Li-Xiong; Lu, Jian-Mei; Wei, Yin; Mizuno, Kazuhiko; Maeda, Hajime (2010-10-13). "Chemistry of Vinylidenecyclopropanes" (in en). Chemical Reviews 110 (10): 5883–5913. doi:10.1021/cr900381k. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 20518460. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cr900381k.

- ↑ Ireland, Robert E.; Mueller, Richard H.; Willard, Alvin K. (May 1976). "The ester enolate Claisen rearrangement. Stereochemical control through stereoselective enolate formation" (in en). Journal of the American Chemical Society 98 (10): 2868–2877. doi:10.1021/ja00426a033. ISSN 0002-7863. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ja00426a033.

- ↑ Kurtz, Kimberly C.M.; Frederick, Michael O.; Lambeth, Robert H.; Mulder, Jason A.; Tracey, Michael R.; Hsung, Richard P. (April 2006). "Synthesis of chiral allenes from ynamides through a highly stereoselective Saucy–Marbet rearrangement" (in en). Tetrahedron 62 (16): 3928–3938. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2005.11.087. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0040402006001268.

- ↑ Mukai, Chisato; Kobayashi, Minoru; Kubota, Shoko; Takahashi, Yukie; Kitagaki, Shinji (March 2004). "Construction of Azacycles Based on Endo-Mode Cyclization of Allenes" (in en). The Journal of Organic Chemistry 69 (6): 2128–2136. doi:10.1021/jo035729f. ISSN 0022-3263. PMID 15058962. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jo035729f.

- ↑ Mukai, Chisato; Ohta, Masaru; Yamashita, Haruhisa; Kitagaki, Shinji (October 2004). "Base-Catalyzed Endo-Mode Cyclization of Allenes: Easy Preparation of Five- to Nine-Membered Oxacycles" (in en). The Journal of Organic Chemistry 69 (20): 6867–6873. doi:10.1021/jo0488614. ISSN 0022-3263. PMID 15387613. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jo0488614.

- ↑ Buckl, Klaus; Meiswinkel, Andreas (2008). "Propyne". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.m22_m01. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Pasto, Daniel J. (January 1984). "Recent developments in allene chemistry" (in en). Tetrahedron 40 (15): 2805–2827. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)91289-X. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S004040200191289X.

- ↑ Ma, Shengming (2009-10-20). "Electrophilic Addition and Cyclization Reactions of Allenes" (in en). Accounts of Chemical Research 42 (10): 1679–1688. doi:10.1021/ar900153r. ISSN 0001-4842. PMID 19603781. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ar900153r.

- ↑ Yu, Shichao; Ma, Shengming (2012-03-26). "Allenes in Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis and Natural Product Syntheses" (in en). Angewandte Chemie International Edition 51 (13): 3074–3112. doi:10.1002/anie.201101460. PMID 22271630. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.201101460.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Ma, Shengming (2005-07-01). "Some Typical Advances in the Synthetic Applications of Allenes" (in en). Chemical Reviews 105 (7): 2829–2872. doi:10.1021/cr020024j. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 16011326. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/cr020024j.

- ↑ Van ’t Hoff, J. H. La Chimie dans l’Espace; P.M. Bazendijk, 1875; p. 43.

- ↑ Fleming, Ian (2010). Molecular orbitals and organic chemical reactions (Reference ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. pp. 526. ISBN 978-0-470-68949-3. OCLC 607520014. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/607520014.

- ↑ Brandsma, L. (2004). Synthesis of acetylenes, allenes and cumulenes : methods and techniques. H. D. Verkruijsse (1st ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-125751-4. OCLC 162570992. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/162570992.

- ↑ Ma, Shengming (2006-01-01). "Transition-metal-catalyzed reactions of allenes". Pure and Applied Chemistry 78 (2): 197–208. doi:10.1351/pac200678020197. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ↑ Bates, Roderick W.; Satcharoen, Vachiraporn (2002-03-06). "Nucleophilic transition metal based cyclization of allenes". Chemical Society Reviews 31 (1): 12–21. doi:10.1039/b103904k. PMID 12108979. http://xlink.rsc.org/?DOI=b103904k.

- ↑ Cherney, Emily C.; Green, Jason C.; Baran, Phil S. (2013-08-19). "Synthesis of ent -Kaurane and Beyerane Diterpenoids by Controlled Fragmentations of Overbred Intermediates" (in en). Angewandte Chemie International Edition 52 (34): 9019–9022. doi:10.1002/anie.201304609. PMID 23861294.

- ↑ Wiesner, K. (August 1975). "On the stereochemistry of photoaddition between α,β-unsaturated ketones and olefins" (in en). Tetrahedron 31 (15): 1655–1658. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(75)85082-4. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0040402075850824.

- ↑ Rahman, W.; Kuivila, Henry G. (March 1966). "Synthesis of Some Alkylidenecyclopropanes from Allenes 1" (in en). The Journal of Organic Chemistry 31 (3): 772–776. doi:10.1021/jo01341a029. ISSN 0022-3263. https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jo01341a029.

- ↑ Krause, Norbert; Hoffmann-Röder, Anja (2004). "18. Allenic Natural Products and Pharmaceuticals". in Krause, Norbert; Hashmi, A. Stephen K.. Modern Allene Chemistry. pp. 997–1040. doi:10.1002/9783527619573.ch18. ISBN 9783527619573.

- ↑ Otsuka, Sei; Nakamura, Akira "Acetylene and allene complexes: their implication in homogeneous catalysis" Advances in Organometallic Chemistry 1976, volume 14, pp. 245-83. doi:10.1016/S0065-3055(08)60654-1.

- ↑ Bhagwat, M. M.; Devaprabhakara, D. (1972). "Selective hydrogenation of allenes with chlorotris-(triphenylphosphine) rhodium catalyst". Tetrahedron Letters 13 (15): 1391–1392. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)84636-0.

- ↑ "Nomenclature for cyclic organic compounds with contiguous formal double bonds (the δ-convention)". Pure Appl. Chem. 60: 1395-1401. 1988. doi:10.1351/pac198860091395. http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iupac/hetero/De.html.

Further reading

- Brummond, Kay M. (editor). Allene chemistry (special thematic issue). Beilstein Journal of Organic Chemistry 7: 394–943.

External links

KSF

KSF