Aromatic hydrocarbon

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 12 min

An aromatic hydrocarbon or arene[1] (or sometimes aryl hydrocarbon)[2] is a hydrocarbon with sigma bonds and delocalized pi electrons between carbon atoms forming a circle. In contrast, aliphatic hydrocarbons lack this delocalization. The term "aromatic" was assigned before the physical mechanism determining aromaticity was discovered, and referred simply to the fact that many such compounds have a sweet or pleasant odour; however, not all aromatic compounds have a sweet odour, and not all compounds with a sweet odour are aromatic. The configuration of six carbon atoms in aromatic compounds is called a "benzene ring", after the simplest possible such hydrocarbon, benzene. Aromatic hydrocarbons can be monocyclic (MAH) or polycyclic (PAH).

Not all aromatic compounds are benzene-based; aromaticity can also manifest in heteroarenes, which follow Hückel's rule (for monocyclic rings: when the number of its π electrons equals 4n + 2, where n = 0, 1, 2, 3, ...). In these compounds, at least one carbon atom is replaced by one of the heteroatoms oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur. Examples of non-benzene compounds with aromatic properties are furan, a heterocyclic compound with a five-membered ring that includes a single oxygen atom, and pyridine, a heterocyclic compound with a six-membered ring containing one nitrogen atom.[3]

Benzene ring model

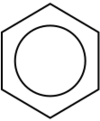

Benzene, C6H6, is the least complex aromatic hydrocarbon, and it was the first one named as such. The nature of its bonding was first recognized by August Kekulé in the 19th century. Each carbon atom in the hexagonal cycle has four electrons to share. One goes to the hydrogen atom, and one to each of the two neighbouring carbons. This leaves one electron to share with one of the two neighbouring carbon atoms, thus creating a double bond with one carbon and leaving a single bond with the other, which is why some representations of the benzene molecule portray it as a hexagon with alternating single and double bonds.

Other depictions of the structure portray the hexagon with a circle inside it, to indicate that the six electrons are floating around in delocalized molecular orbitals the size of the ring itself. This represents the equivalent nature of the six carbon–carbon bonds all of bond order 1.5; the equivalency is explained by resonance forms. The electrons are visualized as floating above and below the ring, with the electromagnetic fields they generate acting to keep the ring flat.

General properties of aromatic hydrocarbons:

- They display aromaticity

- The carbon–hydrogen ratio is high

- They burn with a strong sooty yellow flame because of the high carbon–hydrogen ratio

- They undergo electrophilic substitution reactions and nucleophilic aromatic substitutions

The circle symbol for aromaticity was introduced by Sir Robert Robinson and his student James Armit in 1925[4] and popularized starting in 1959 by the Morrison & Boyd textbook on organic chemistry. The proper use of the symbol is debated: some publications use it to any cyclic π system, while others use it only for those π systems that obey Hückel's rule. Jensen[5] argues that, in line with Robinson's original proposal, the use of the circle symbol should be limited to monocyclic 6 π-electron systems. In this way the circle symbol for a six-center six-electron bond can be compared to the Y symbol for a three-center two-electron bond.

Arene synthesis

A reaction that forms an arene compound from an unsaturated or partially unsaturated cyclic precursor is simply called an aromatization. Many laboratory methods exist for the organic synthesis of arenes from non-arene precursors. Many methods rely on cycloaddition reactions. Alkyne trimerization describes the [2+2+2] cyclization of three alkynes, in the Dötz reaction an alkyne, carbon monoxide and a chromium carbene complex are the reactants. Diels–Alder reactions of alkynes with pyrone or cyclopentadienone with expulsion of carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide also form arene compounds. In Bergman cyclization the reactants are an enyne plus a hydrogen donor.

Another set of methods is the aromatization of cyclohexanes and other aliphatic rings: reagents are catalysts used in hydrogenation such as platinum, palladium and nickel (reverse hydrogenation), quinones and the elements sulfur and selenium.[6]

Arene reactions

Arenes are reactants in many organic reactions.

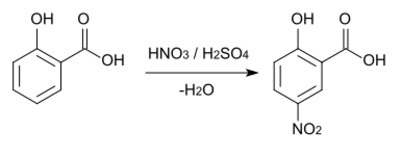

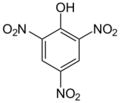

In aromatic substitution one substituent on the arene ring, usually hydrogen, is replaced by another substituent. The two main types are electrophilic aromatic substitution when the active reagent is an electrophile and nucleophilic aromatic substitution when the reagent is a nucleophile. In radical-nucleophilic aromatic substitution the active reagent is a radical. An example of electrophilic aromatic substitution is the nitration of salicylic acid:[7]

Coupling reactions

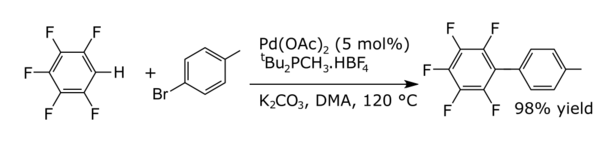

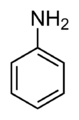

In coupling reactions a metal catalyses a coupling between two formal radical fragments. Common coupling reactions with arenes result in the formation of new carbon–carbon bonds e.g., alkylarenes, vinyl arenes, biraryls, new carbon–nitrogen bonds (anilines) or new carbon–oxygen bonds (aryloxy compounds). An example is the direct arylation of perfluorobenzenes [8]

Hydrogenation

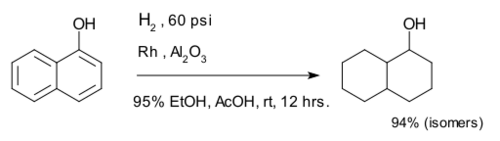

Hydrogenation of arenes create saturated rings. The compound 1-naphthol is completely reduced to a mixture of decalin-ol isomers.[9]

The compound resorcinol, hydrogenated with Raney nickel in presence of aqueous sodium hydroxide forms an enolate which is alkylated with methyl iodide to 2-methyl-1,3-cyclohexandione:[10]

Cycloadditions

Cycloaddition reaction are not common. Unusual thermal Diels–Alder reactivity of arenes can be found in the Wagner-Jauregg reaction. Other photochemical cycloaddition reactions with alkenes occur through excimers.

Dearomatization

In dearomatization reactions the aromaticity of the reactant is permanently lost.

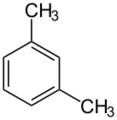

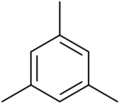

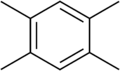

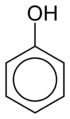

Benzene and derivatives of benzene

Benzene derivatives have from one to six substituents attached to the central benzene core. Examples of benzene compounds with just one substituent are phenol, which carries a hydroxyl group, and toluene with a methyl group. When there is more than one substituent present on the ring, their spatial relationship becomes important for which the arene substitution patterns ortho, meta, and para are devised. For example, three isomers exist for cresol because the methyl group and the hydroxyl group can be placed next to each other (ortho), one position removed from each other (meta), or two positions removed from each other (para). Xylenol has two methyl groups in addition to the hydroxyl group, and, for this structure, 6 isomers exist.

- Representative arene compounds

The arene ring has an ability to stabilize charges. This is seen in, for example, phenol (C6H5–OH), which is acidic at the hydroxyl (OH), since a charge on this oxygen (alkoxide –O−) is partially delocalized into the benzene ring.

Other monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbon

Other monocyclic aromatic hydrocarbon include Cyclotetradecaheptaene or Cyclooctadecanonaene.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are aromatic hydrocarbons that consist of fused aromatic rings and do not contain heteroatoms or carry substituents.[11] Naphthalene is the simplest example of a PAH. PAHs occur in oil, coal, and tar deposits, and are produced as byproducts of fuel burning (whether fossil fuel or biomass). As pollutants, they are of concern because some compounds have been identified as carcinogenic, mutagenic, and teratogenic. PAHs are also found in cooked foods. Studies have shown that high levels of PAHs are found, for example, in meat cooked at high temperatures such as grilling or barbecuing, and in smoked fish.[12][13][14]

They are also found in the interstellar medium, in comets, and in meteorites and are a candidate molecule to act as a basis for the earliest forms of life. In graphene the PAH motif is extended to large 2D sheets.

See also

- Aromatic substituents: Aryl, Aryloxy and Arenediyl

- Asphaltene

- Hydrodealkylation

- Simple aromatic rings

- Rhodium-platinum oxide, a catalyst used to hydrogenate aromatic compounds.

References

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "arenes". doi:10.1351/goldbook.A00435

- ↑ Mechanisms of Activation of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor by Maria Backlund, Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet.

- ↑ HighBeam Encyclopedia: aromatic compound.

- ↑ Armit, James Wilkins; Robinson, Robert (1925). "Polynuclear heterocyclic aromatic types. Part II. Some anhydronium bases". J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 127: 1604–1618.

- ↑ Jensen, William B. (April 2009). "The circle symbol for aromaticity". J. Chem. Educ. 86 (4): 423–424. doi:10.1021/ed086p423. Bibcode: 2009JChEd..86..423J. http://www.che.uc.edu/jensen/W.%20B.%20Jensen/Reprints/157.%20Aromaticity%20Circle.pdf.

- ↑ March, Jerry (1985), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (3rd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-85472-7

- ↑ Webb, K.; Seneviratne, V. (1995). "A mild oxidation of aromatic amines". Tetrahedron Letters 36 (14): 2377–2378. doi:10.1016/0040-4039(95)00281-G.

- ↑ Lafrance, M.; Rowley, C.; Woo, T.; Fagnou, K. (2006). "Catalytic intermolecular direct arylation of perfluorobenzenes.". Journal of the American Chemical Society 128 (27): 8754–8756. doi:10.1021/ja062509l. PMID 16819868.

- ↑ Meyers, A. I.; Beverung, W. N.; Gault, R.. "1-Naphthol". Organic Syntheses 51: 103. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=CV6P0371.; Collective Volume, 6

- ↑ Noland, Wayland E.; Baude, Frederic J.. "Ethyl Indole-2-carboxylate". Organic Syntheses 41: 56. http://www.orgsyn.org/demo.aspx?prep=CV5P0567.; Collective Volume, 5

- ↑ Fetzer, J. C. (2000). "The Chemistry and Analysis of the Large Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons". Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds (New York: Wiley) 27 (2): 143. doi:10.1080/10406630701268255. ISBN 0-471-36354-5.

- ↑ "Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons – Occurrence in foods, dietary exposure and health effects". European Commission, Scientific Committee on Food. December 4, 2002. http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/scf/out154_en.pdf.

- ↑ Larsson, B. K.; Sahlberg, GP; Eriksson, AT; Busk, LA (1983). "Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in grilled food". J. Agric. Food Chem. 31 (4): 867–873. doi:10.1021/jf00118a049. PMID 6352775.

- ↑ "Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)". Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. 1996. http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxfaqs/tf.asp?id=121&tid=25.

External links

KSF

KSF