Coenzyme Q10

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

This article is missing information about biological function (weight too low compared to dietary), need a section with links to Q cycle and Complex III at minimum. (September 2022) |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-[(2E,6E,10E,14E,18E,22E,26E,30E,34E)-3,7,11,15,19,23,27,31,35,39-Decamethyltetraconta-2,6,10,14,18,22,26,30,34,38-decaen-1-yl]-5,6-dimethoxy-3-methylcyclohexa-2,5-diene-1,4-dione | |

Other names

Q10, CoQ10 /ˌkoʊˌkjuːˈtɛn/ | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C59H90O4 | |

| Molar mass | 863.365 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | yellow or orange solid |

| Melting point | 48–52 °C (118–126 °F; 321–325 K) |

| insoluble | |

| Pharmacology | |

| 1=ATC code }} | C01EB09 (WHO) |

| Related compounds | |

Related quinones

|

1,4-Benzoquinone Plastoquinone Ubiquinol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Coenzyme Q is a coenzyme family that is ubiquitous in animals and many Pseudomonadota[1] (hence its other name, ubiquinone). In humans, the most common form is coenzyme Q10, also called CoQ10 (/ˌkoʊkjuːˈtɛn/) or ubiquinone-10.

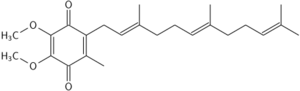

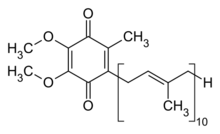

Coenzyme Q10 is a 1,4-benzoquinone, in which Q refers to the quinone chemical group and 10 refers to the number of isoprenyl chemical subunits (shown enclosed in brackets in the diagram) in its tail. In natural ubiquinones, there are from six to ten subunits in the tail.

This family of fat-soluble substances, which resemble vitamins, is present in all respiring eukaryotic cells, primarily in the mitochondria. It is a component of the electron transport chain and participates in aerobic cellular respiration, which generates energy in the form of ATP. Ninety-five percent of the human body's energy is generated this way.[2][3] Organs with the highest energy requirements—such as the heart, liver, and kidney—have the highest CoQ10 concentrations.[4][5][6]

There are three redox states of CoQ: fully oxidized (ubiquinone), semiquinone (ubisemiquinone), and fully reduced (ubiquinol). The capacity of this molecule to act as a two-electron carrier (moving between the quinone and quinol form) and a one-electron carrier (moving between the semiquinone and one of these other forms) is central to its role in the electron transport chain due to the iron–sulfur clusters that can only accept one electron at a time, and as a free-radical–scavenging antioxidant.

Deficiency and toxicity

There are two major pathways of deficiency of CoQ10 in humans: reduced biosynthesis, and increased use by the body. Biosynthesis is the major source of CoQ10. Biosynthesis requires at least 12 genes, and mutations in many of them cause CoQ deficiency. CoQ10 levels also may be affected by other genetic defects (such as mutations of mitochondrial DNA, ETFDH, APTX, FXN, and BRAF, genes that are not directly related to the CoQ10 biosynthetic process). Some of these, such as mutations in COQ6, can lead to serious diseases such as steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome with sensorineural deafness.

Some adverse effects, largely gastrointestinal, are reported with very high intakes. The observed safe level (OSL) risk assessment method indicated that the evidence of safety is strong at intakes up to 1200 mg/day, and this level is identified as the OSL.[7]

Assessment

Although CoQ10 may be measured in blood plasma, these measurements reflect dietary intake rather than tissue status. Currently, most clinical centers measure CoQ10 levels in cultured skin fibroblasts, muscle biopsies, and blood mononuclear cells.[8] Culture fibroblasts can be used also to evaluate the rate of endogenous CoQ10 biosynthesis, by measuring the uptake of 14C-labelled p-hydroxybenzoate.[9]

Statins

While statins may reduce coenzyme Q10 in the blood it is unclear if they reduce coenzyme Q10 in muscle.[10] Evidence does not support that supplementation improves side effects from statins.[10] However, a more recent metanalysis conducted in China, one of the world's largest producers of this supplement, concluded that, "CoQ10 supplementation ameliorated SAMSs [statin‐associated muscle symptoms], implying that CoQ10 supplementation might be a complementary approach to ameliorate statin‐induced myopathy."[11]

Dietary supplement

Regulation and composition

CoQ10 is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of any medical condition.[12][13] However, it is sold as a dietary supplement in the name of UbiQ 300 & UbiQ 100, not subject to the same regulations as medicinal drugs, and is an ingredient in some cosmetics.[14][15] The manufacture of CoQ10 is not regulated, and different batches and brands may vary significantly:[12] a 2004 laboratory analysis by ConsumerLab.com of CoQ10 supplements on sale in the US found that some did not contain the quantity identified on the product label. Amounts ranged from "no detectable CoQ10", through 75% of stated dose, up to a 75% excess.[16][17]

Generally, CoQ10 is well tolerated. The most common side effects are gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, appetite suppression, and abdominal pain), rashes, and headaches.[18]

While there is no established ideal dosage of CoQ10, a typical daily dose is 100–200 milligrams. Different formulations have varying declared amounts of CoQ10 and other ingredients.

Heart disease

A 2014 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to make a conclusion about its use for the prevention of heart disease.[19] A 2016 Cochrane review concluded that CoQ10 had no effect on blood pressure.[20] A 2021 Cochrane review found "no convincing evidence to support or refute" the use of CoQ10 for the treatment of heart failure.[21]

In a 2017 meta-analysis of people with heart failure 30–100 mg/d of CoQ10 resulted in 31% lower mortality. Exercise capacity was also increased. No significant difference was found in the endpoints of left heart ejection fraction and New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification.[22]

In a 2023 meta-analysis of older people ubiquinone was compared with ubiquinol. The results demonstrate a beneficial cardiovascular effect of ubichinone. This could not be confirmed for ubiquinol.[23]

Migraine headaches

The Canadian Headache Society guideline for migraine prophylaxis recommends, based on low-quality evidence, that 300 mg of CoQ10 be offered as a choice for prophylaxis.[24]

Statin myopathy

Although CoQ10 has been used to treat purported muscle-related side effects of statin medications, a 2015 meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that CoQ10 had no effect on statin myopathy.[25] A 2018 meta-analysis concluded that there was preliminary evidence for oral CoQ10 reducing statin-associated muscle symptoms, including muscle pain, muscle weakness, muscle cramps and muscle tiredness.[11]

Cancer

(As of 2014) no large clinical trials of CoQ10 in cancer treatment had been conducted.[12] The US's National Cancer Institute identified issues with the few, small studies that had been carried out, stating, "the way the studies were done and the amount of information reported made it unclear if benefits were caused by the CoQ10 or by something else".[12] The American Cancer Society concluded, "CoQ10 may reduce the effectiveness of chemo and radiation therapy, so most oncologists would recommend avoiding it during cancer treatment."[26]

Dental disease

A 1995 review study found that there is no clinical benefit to the use of CoQ10 in the treatment of periodontal disease.[27]

Chronic kidney disease

A review of the effects of CoQ10 supplementation in people with CKD was proposed in 2019.[28]

Additional uses

Coenzyme Q10 has also been utilized as an active ingredient in cosmeceuticals and as an inactive ingredient in sunscreen formulations. When applied topically in skincare products it demonstrates some ability to reduce oxidative stress in the skin,[29] delay signs of intrinsic skin aging, reverse signs of extrinsic skin aging,[30][31] assist in fading dyspigmentation,[32][33] increase stability of certain sunscreen actives,[34] increase the SPF of sunscreens,[35] and afford some infrared protection to sunscreens.[36][37] Much of the research on the skin benefits of ubiquinone show that it works synergistically with other topical antioxidants to improve the skin and cosmetic formulations.

Interactions

Coenzyme Q10 has potential to inhibit the effects of theophylline as well as the anticoagulant warfarin; coenzyme Q10 may interfere with warfarin's actions by interacting with cytochrome p450 enzymes thereby reducing the INR, a measure of blood clotting.[38] The structure of coenzyme Q10 is very similar to that of vitamin K, which competes with and counteracts warfarin's anticoagulation effects. Coenzyme Q10 should be avoided in patients currently taking warfarin due to the increased risk of clotting.[18]

Chemical properties

The oxidized structure of CoQ10 is shown below. The various kinds of Coenzyme Q may be distinguished by the number of isoprenoid subunits in their side-chains. The most common coenzyme Q in human mitochondria is CoQ10. Q refers to the quinone head and 10 refers to the number of isoprene repeats in the tail. The molecule below has three isoprenoid units and would be called Q3.

In its pure state, it is an orange-coloured lipophile powder, and has no taste nor odour.[39]:230

Biosynthesis

Biosynthesis occurs in most human tissue. There are three major steps:

- Creation of the benzoquinone structure (using phenylalanine or tyrosine, via 4-hydroxybenzoate)

- Creation of the isoprene side chain (using acetyl-CoA)

- The joining or condensation of the above two structures

The initial two reactions occur in mitochondria, the endoplasmic reticulum, and peroxisomes, indicating multiple sites of synthesis in animal cells.[40]

An important enzyme in this pathway is HMG-CoA reductase, usually a target for intervention in cardiovascular complications. The "statin" family of cholesterol-reducing medications inhibits HMG-CoA reductase. One possible side effect of statins is decreased production of CoQ10, which may be connected to the development of myopathy and rhabdomyolysis. However, the role statins play in CoQ deficiency is controversial. Although statins reduce blood levels of CoQ, studies on the effects of muscle levels of CoQ are yet to come. CoQ supplementation also does not reduce side effects of statin medications.[8][10]

Genes involved include PDSS1, PDSS2, COQ2, and ADCK3 (COQ8, CABC1).[41]

Organisms other than human use somewhat different source chemicals to produce the benzoquinone structure and the isoprene structure. For example, the bacteria E. coli produces the former from chorismate and the latter from a non-mevalonate source. The common yeast S. cerevisiae, however, derives the former from either chorismate or tyrosine and the latter from mevalonate. Most organisms share the common 4-hydroxybenzoate intermediate, yet again uses different steps to arrive at the "Q" structure.[42]

Absorption and metabolism

Absorption

CoQ10 is a crystalline powder insoluble in water. Absorption follows the same process as that of lipids; the uptake mechanism appears to be similar to that of vitamin E, another lipid-soluble nutrient. This process in the human body involves secretion into the small intestine of pancreatic enzymes and bile, which facilitates emulsification and micelle formation required for absorption of lipophilic substances.[43] Food intake (and the presence of lipids) stimulates bodily biliary excretion of bile acids and greatly enhances absorption of CoQ10. Exogenous CoQ10 is absorbed from the small intestine and is best absorbed if taken with a meal. Serum concentration of CoQ10 in fed condition is higher than in fasting conditions.[44][45]

Metabolism

Data on the metabolism of CoQ10 in animals and humans are limited.[46] A study with 14C-labeled CoQ10 in rats showed most of the radioactivity in the liver two hours after oral administration when the peak plasma radioactivity was observed, but CoQ9 (with only 9 isoprenyl units) is the predominant form of coenzyme Q in rats.[47] It appears that CoQ10 is metabolised in all tissues, while a major route for its elimination is biliary and fecal excretion. After the withdrawal of CoQ10 supplementation, the levels return to normal within a few days, irrespective of the type of formulation used.[48]

Pharmacokinetics

Some reports have been published on the pharmacokinetics of CoQ10. The plasma peak can be observed 2–6 hours after oral administration, depending mainly on the design of the study. In some studies, a second plasma peak also was observed at approximately 24 hours after administration, probably due to both enterohepatic recycling and redistribution from the liver to circulation.[43] Tomono et al. used deuterium-labeled crystalline CoQ10 to investigate pharmacokinetics in humans and determined an elimination half-time of 33 hours.[49]

Improving the bioavailability of CoQ10

The importance of how drugs are formulated for bioavailability is well known. In order to find a principle to boost the bioavailability of CoQ10 after oral administration, several new approaches have been taken; different formulations and forms have been developed and tested on animals and humans.[46]

Reduction of particle size

Nanoparticles have been explored as a delivery system for various drugs, such as improving the oral bioavailability of drugs with poor absorption characteristics.[50] However, this has not proved successful with CoQ10, although reports have differed widely.[51][52] The use of aqueous suspension of finely powdered CoQ10 in pure water also reveals only a minor effect.[48]

Soft-gel capsules with CoQ10 in oil suspension

A successful approach is to use the emulsion system to facilitate absorption from the gastrointestinal tract and to improve bioavailability. Emulsions of soybean oil (lipid microspheres) could be stabilised very effectively by lecithin and were used in the preparation of softgel capsules. In one of the first such attempts, Ozawa et al. performed a pharmacokinetic study on beagles in which the emulsion of CoQ10 in soybean oil was investigated; about twice the plasma CoQ10 level than that of the control tablet preparation was determined during administration of a lipid microsphere.[48] Although an almost negligible improvement of bioavailability was observed by Kommuru et al. with oil-based softgel capsules in a later study on dogs,[53] the significantly increased bioavailability of CoQ10 was confirmed for several oil-based formulations in most other studies.[54]

Novel forms of CoQ10 with increased water-solubility

Facilitating drug absorption by increasing its solubility in water is a common pharmaceutical strategy and also has been shown to be successful for CoQ10. Various approaches have been developed to achieve this goal, with many of them producing significantly better results over oil-based softgel capsules in spite of the many attempts to optimize their composition.[46] Examples of such approaches are use of the aqueous dispersion of solid CoQ10 with the polymer tyloxapol,[55] formulations based on various solubilising agents, such as hydrogenated lecithin,[56] and complexation with cyclodextrins; among the latter, the complex with β-cyclodextrin has been found to have highly increased bioavailability[57][58] and also is used in pharmaceutical and food industries for CoQ10-fortification.[46]

History

In 1950, G. N. Festenstein was the first to isolate a small amount of CoQ10 from the lining of a horse's gut at Liverpool, England. In subsequent studies the compound was briefly called substance SA, it was deemed to be quinone, and it was noted that it could be found from many tissues of a number of animals.[59]

In 1957, Frederick L. Crane and colleagues at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Enzyme Institute isolated the same compound from mitochondrial membranes of beef heart and noted that it transported electrons within mitochondria. They called it Q-275 for short as it was a quinone.[60][59] Soon they noted that Q-275 and substance SA studied in England may be the same compound. This was confirmed later that year and Q-275/substance SA was renamed ubiquinone as it was a ubiquitous quinone that could be found from all animal tissues.[59][39]

In 1958, its full chemical structure was reported by D. E. Wolf and colleagues working under Karl Folkers at Merck in Rahway.[61][59][39] Later that year D. E. Green and colleagues belonging to the Wisconsin research group suggested that ubiquinone should be called either mitoquinone or coenzyme Q due to its participation to the mitochondrial electron transport chain.[59][39]

In 1966, A. Mellors and A. L. Tappel at the University of California were the first to show that reduced CoQ6 was an effective antioxidant in cells.[62][39]

In 1960s Peter D. Mitchell enlarged upon the understanding of mitochondrial function via his theory of electrochemical gradient, which involves CoQ10, and in late 1970s studies of Lars Ernster enlargened upon the importance of CoQ10 as an antioxidant. The 1980s witnessed a steep rise in the number of clinical trials involving CoQ10.[39]

Dietary concentrations

Detailed reviews on occurrence of CoQ10 and dietary intake were published in 2010.[63] Besides the endogenous synthesis within organisms, CoQ10 also is supplied to the organism by various foods. Despite the scientific community's great interest in this compound, however, a very limited number of studies have been performed to determine the contents of CoQ10 in dietary components. The first reports on this aspect were published in 1959, but the sensitivity and selectivity of the analytical methods at that time did not allow reliable analyses, especially for products with low concentrations.[63] Since then, developments in analytical chemistry have enabled a more reliable determination of CoQ10 concentrations in various foods:

| Food | CoQ10 concentration (mg/kg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Oils | soybean | 54–280 |

| olive | 40–160 | |

| grapeseed | 64–73 | |

| sunflower | 4–15 | |

| canola | 64–73 | |

| Beef | heart | 113 |

| liver | 39–50 | |

| muscle | 26–40 | |

| Pork | heart | 12–128 |

| liver | 23–54 | |

| muscle | 14–45 | |

| Chicken | breast | 8–17 |

| thigh | 24–25 | |

| wing | 11 | |

| Fish | sardine | 5–64 |

| mackerel: | ||

| – red flesh | 43–67 | |

| – white flesh | 11–16 | |

| salmon | 4–8 | |

| tuna | 5 | |

| Nuts | peanut | 27 |

| walnut | 19 | |

| sesame seed | 18–23 | |

| pistachio | 20 | |

| hazelnut | 17 | |

| almond | 5–14 | |

| Vegetables | parsley | 8–26 |

| broccoli | 6–9 | |

| cauliflower | 2–7 | |

| spinach | up to 10 | |

| Chinese cabbage | 2–5 | |

| Fruit | avocado | 10 |

| blackcurrant | 3 | |

| grape | 6–7 | |

| strawberry | 1 | |

| orange | 1–2 | |

| grapefruit | 1 | |

| apple | 1 | |

| banana | 1 | |

Vegetable oils are the richest sources of dietary CoQ10; Meat and fish also are quite rich in CoQ10 levels over 50 mg/kg may be found in beef, pork, and chicken heart and liver. Dairy products are much poorer sources of CoQ10 than animal tissues. Among vegetables, parsley and perilla are the richest CoQ10 sources, but significant differences in their CoQ10 levels may be found in the literature. Broccoli, grapes, and cauliflower are modest sources of CoQ10. Most fruit and berries represent a poor to very poor source of CoQ10, with the exception of avocados, which have a relatively high CoQ10 content.[63]

Intake

In the developed world, the estimated daily intake of CoQ10 has been determined at 3–6 mg per day, derived primarily from meat.[63]

South Koreans have an estimated average daily CoQ (Q9 + Q10) intake of 11.6 mg/d, derived primarily from kimchi.[64]

Effect of heat and processing

Cooking by frying reduces CoQ10 content by 14–32%.[65]

See also

- Idebenone – synthetic analog with reduced oxidant generating properties

- Mitoquinone mesylate – synthetic analog with improved mitochondrial permeability

References

- ↑ "Occurrence, biosynthesis and function of isoprenoid quinones". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1797 (9): 1587–2105. 2010. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.06.007. PMID 20599680.

- ↑ "Biochemical, physiological and medical aspects of ubiquinone function". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 1271 (1): 195–204. May 1995. doi:10.1016/0925-4439(95)00028-3. PMID 7599208.

- ↑ Dutton, P. L.; Ohnishi, T.; Darrouzet, E.; Leonard, M. A.; Sharp, R. E.; Cibney, B. R.; Daldal, F.; Moser, C. C. (2000). "4 Coenzyme Q oxidation reduction reactions in mitochondrial electron transport". in Kagan, V. E.. Coenzyme Q: Molecular mechanisms in health and disease. Boca Raton: CRC Press. pp. 65–82.

- ↑ "Human serum ubiquinol-10 levels and relationship to serum lipids". International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. Internationale Zeitschrift für Vitamin- und Ernahrungsforschung. Journal International de Vitaminologie et de Nutrition 59 (3): 288–92. 1989. PMID 2599795.

- ↑ "Distribution and redox state of ubiquinones in rat and human tissues". Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 295 (2): 230–4. June 1992. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(92)90511-T. PMID 1586151.

- ↑ "Enzymic and non-enzymic antioxidants in epidermis and dermis of human skin". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 102 (1): 122–4. January 1994. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12371744. PMID 8288904.

- ↑ "Risk assessment for coenzyme Q10 (Ubiquinone)". Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 45 (3): 282–8. August 2006. doi:10.1016/j.yrtph.2006.05.006. PMID 16814438.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Coenzyme Q deficiency in muscle". Current Opinion in Neurology 24 (5): 449–56. October 2011. doi:10.1097/WCO.0b013e32834ab528. PMID 21844807.

- ↑ "Analysis of coenzyme Q10 in muscle and fibroblasts for the diagnosis of CoQ10 deficiency syndromes". Clinical Biochemistry 41 (9): 697–700. June 2008. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2008.03.007. PMID 18387363.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Coenzyme Q10 supplementation in the management of statin-associated myalgia". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 74 (11): 786–793. June 2017. doi:10.2146/ajhp160714. PMID 28546301.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Effects of Coenzyme Q10 on Statin-Induced Myopathy: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials". Journal of the American Heart Association 7 (19): e009835. October 2018. doi:10.1161/JAHA.118.009835. PMID 30371340.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 White, J. (14 May 2014). "PDQ® Coenzyme Q10". National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/cam/coenzymeQ10/HealthProfessional.

- ↑ "Mitochondrial disorders in children: Co-enzyme Q10". UK: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 28 March 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/advice/es11/resources/mitochondrial-disorders-in-children-coenzyme-q10-pdf-1158110303173.

- ↑ Hojerová, J (May 2000). "[Coenzyme Q10--its importance, properties and use in nutrition and cosmetics].". Ceska a Slovenska Farmacie: Casopis Ceske Farmaceuticke Spolecnosti a Slovenske Farmaceuticke Spolecnosti 49 (3): 119–23. PMID 10953455.

- ↑ "What is coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) and why is it in skin care products?" (in en). https://www.webmd.com/beauty/qa/what-is-coenzyme-q10-coq10-and-why-is-it-in-skin-care-products.

- ↑ "ConsumerLab.com finds discrepancies in strength of CoQ10 supplements". Townsend Letter for Doctors and Patients: p. 19. Aug–Sep 2004.

- ↑ "ConsumerLab.com finds discrepancies in strength of CoQ10 supplements". Jan 2004. https://www.consumerlab.com/news/coq10-coenzyme-q10-tests/01-13-2004/.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Coenzyme Q10: a therapy for hypertension and statin-induced myalgia?". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 77 (7): 435–42. July 2010. doi:10.3949/ccjm.77a.09078. PMID 20601617.

- ↑ "Co-enzyme Q10 supplementation for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014 (12): CD010405. 4 December 2014. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010405.pub2. PMID 25474484.

- ↑ "Blood pressure lowering efficacy of coenzyme Q10 for primary hypertension". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 (3): CD007435. March 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007435.pub3. PMID 26935713.

- ↑ Al Saadi, Tareq; Assaf, Yazan; Farwati, Medhat; Turkmani, Khaled; Al-Mouakeh, Ahmad; Shebli, Baraa; Khoja, Mohammed; Essali, Adib et al. (2021-02-03). Cochrane Heart Group. ed. "Coenzyme Q10 for heart failure" (in en). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021 (2): CD008684. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008684.pub3. PMID 35608922.

- ↑ "Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in patients with cardiac failure: a meta-analysis of clinical trials". BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 17 (1): 196. July 2017. doi:10.1186/s12872-017-0628-9. PMID 28738783.

- ↑ Fladerer, Johannes-Paul; Grollitsch, Selina (16 November 2023). "Comparison of Coenzyme Q10 (Ubiquinone) and Reduced Coenzyme Q10 (Ubiquinol) as Supplement to Prevent Cardiovascular Disease and Reduce Cardiovascular Mortality". Current Cardiology Reports. doi:10.1007/s11886-023-01992-6.

- ↑ "Canadian Headache Society guideline for migraine prophylaxis". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences 39 (2 Suppl 2): S1-59. March 2012. PMID 22683887.

- ↑ "Effects of coenzyme Q10 on statin-induced myopathy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Mayo Clinic Proceedings 90 (1): 24–34. January 2015. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.08.021. PMID 25440725.

- ↑ "Coenzyme Q10". American Cancer Society. http://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatmentsandsideeffects/complementaryandalternativemedicine/pharmacologicalandbiologicaltreatment/coenzyme-q10.

- ↑ "Coenzyme Q10 and periodontal treatment: is there any beneficial effect?". British Dental Journal 178 (6): 209–13. March 1995. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4808715. PMID 7718355.

- ↑ Xu, Yongxing; Liu, Juan; Han, Enhong; Wang, Yan; Gao, Jianjun (2019). "Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in patients with chronic kidney disease: protocol for a systematic review". BMJ Open 9 (5): e029053. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029053. ISSN 2044-6055. PMID 31092669.

- ↑ Knott, Anja; Achterberg, Volker; Smuda, Christoph; Mielke, Heiko; Sperling, Gabi; Dunckelmann, Katja; Vogelsang, Alexandra; Krüger, Andrea et al. (2015-11-12). "Topical treatment with coenzyme Q10-containing formulas improves skin's Q10 level and provides antioxidative effects". Biofactors 41 (6): 383–390. doi:10.1002/biof.1239. ISSN 0951-6433. PMID 26648450.

- ↑ Addor, Flavia Alvim Sant'anna (2017). "Antioxidants in dermatology". Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia 92 (3): 356–362. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20175697. ISSN 0365-0596. PMID 29186248.

- ↑ Blatt, Thomas; Wittern, Klaus-Peter; Wenck, Horst; Staeb, Franz (2004-03-01). "CoQ10, a topical energizer for aging skin" (in English). Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 50 (3): P76. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2003.10.628. ISSN 0190-9622. https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(03)03634-X/abstract.

- ↑ Zhang, M.; Dang, L.; Guo, F.; Wang, X.; Zhao, W.; Zhao, R. (June 2012). "Coenzyme Q(10) enhances dermal elastin expression, inhibits IL-1α production and melanin synthesis in vitro". International Journal of Cosmetic Science 34 (3): 273–279. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2494.2012.00713.x. ISSN 1468-2494. PMID 22339577. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22339577/.

- ↑ Hseu, You-Cheng; Ho, Yi-Geng; Mathew, Dony Chacko; Yen, Hung-Rong; Chen, Xuan-Zao; Yang, Hsin-Ling (2019-06-01). "The in vitro and in vivo depigmenting activity of Coenzyme Q10 through the down-regulation of α-MSH signaling pathways and induction of Nrf2/ARE-mediated antioxidant genes in UVA-irradiated skin keratinocytes" (in en). Biochemical Pharmacology 164: 299–310. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2019.04.015. ISSN 0006-2952. PMID 30991050. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006295219301509.

- ↑ Afonso, S.; Horita, K.; Sousa e Silva, J. P.; Almeida, I. F.; Amaral, M. H.; Lobão, P. A.; Costa, P. C.; Miranda, Margarida S. et al. (November 2014). "Photodegradation of avobenzone: stabilization effect of antioxidants". Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 140: 36–40. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.07.004. ISSN 1873-2682. PMID 25086322. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25086322/.

- ↑ Wu, Haiyou; Zhong, Zhangfeng; Lin, Sien; Qiu, Chuqun; Xie, Peitao; Lv, Simin; Cui, Liao; Wu, Tie (2020-08-19). "Coenzyme Q10 Sunscreen Prevents Progression of Ultraviolet-Induced Skin Damage in Mice" (in en). BioMed Research International 2020: 1–8. doi:10.1155/2020/9039843. PMID 32923487.

- ↑ Grether-Beck, Susanne; Marini, Alessandra; Jaenicke, Thomas; Krutmann, Jean (January 2015). "Effective photoprotection of human skin against infrared A radiation by topically applied antioxidants: results from a vehicle controlled, double-blind, randomized study". Photochemistry and Photobiology 91 (1): 248–250. doi:10.1111/php.12375. ISSN 1751-1097. PMID 25349107. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25349107/.

- ↑ Lim, Henry W.; Arellano-Mendoza, Maria-Ivonne; Stengel, Fernando (March 2017). "Current challenges in photoprotection". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 76 (3S1): S91–S99. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.040. ISSN 1097-6787. PMID 28038886.

- ↑ Sharma, A; Fonarow, GC; Butler, J; Ezekowitz, JA; Felker, GM (April 2016). "Coenzyme Q10 and Heart Failure: A State-of-the-Art Review". Circulation: Heart Failure 9 (4): e002639. doi:10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002639. PMID 27012265.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 "Nourishing and health benefits of coenzyme Q10". Czech Journal of Food Sciences 26 (4): 229–241. 2008. doi:10.17221/1122-cjfs.

- ↑ "Coenzyme Q--biosynthesis and functions". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 396 (1): 74–9. May 2010. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.147. PMID 20494114.

- ↑ Espinós, Carmen; Felipo, Vicente; Palau, Francesc (2009). Inherited Neuromuscular Diseases: Translation from Pathomechanisms to Therapies. Springer. pp. 122ff. ISBN 978-90-481-2812-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=uxQ_pjKNhE8C&pg=PA122. Retrieved 4 January 2011.

- ↑ "Ubiquinone biosynthesis in microorganisms". FEMS Microbiology Letters 203 (2): 131–9. September 2001. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10831.x. PMID 11583838.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Coenzyme Q10: absorption, tissue uptake, metabolism and pharmacokinetics". Free Radical Research 40 (5): 445–53. May 2006. doi:10.1080/10715760600617843. PMID 16551570.

- ↑ Bogentoft 1991[verification needed]

- ↑ "Improvement in intestinal coenzyme q10 absorption by food intake". Yakugaku Zasshi 127 (8): 1251–4. August 2007. doi:10.1248/yakushi.127.1251. PMID 17666877.[verification needed]

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 Žmitek (2008). "Improving the bioavailability of CoQ10". Agro Food Industry Hi Tech 19 (4): 9. http://www.teknoscienze.com/leafpdf/schema/index.html?folder=144&pagina=10. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ↑ Kishi, H.; Kanamori, N.; Nisii, S.; Hiraoka, E.; Okamoto, T.; Kishi, T. (1964). "Metabolism and Exogenous Coenzyme Q10 in vivo and Bioavailability of Coenzyme Q10 Preparations in Japan". Biomedical and Clinical Aspects of Coenzyme Q. Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 131–142.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 "Intestinal absorption enhancement of coenzyme Q10 with a lipid microsphere". Arzneimittel-Forschung 36 (4): 689–90. April 1986. PMID 3718593.

- ↑ "Pharmacokinetic study of deuterium-labelled coenzyme Q10 in man". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Therapy, and Toxicology 24 (10): 536–41. October 1986. PMID 3781673.

- ↑ "Biologically erodable microspheres as potential oral drug delivery systems". Nature 386 (6623): 410–4. March 1997. doi:10.1038/386410a0. PMID 9121559. Bibcode: 1997Natur.386..410M.

- ↑ "Preparation and characterization of novel coenzyme Q10 nanoparticles engineered from microemulsion precursors". AAPS PharmSciTech 4 (3): E32. 2003. doi:10.1208/pt040332. PMID 14621964.[verification needed]

- ↑ "Comparative bioavailability of two novel coenzyme Q10 preparations in humans". International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 41 (1): 42–8. January 2003. doi:10.5414/CPP41042. PMID 12564745.[verification needed]

- ↑ "Stability and bioequivalence studies of two marketed formulations of coenzyme Q10 in beagle dogs". Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 47 (7): 1024–8. July 1999. doi:10.1248/cpb.47.1024. PMID 10434405.

- ↑ "Plasma coenzyme Q10 response to oral ingestion of coenzyme Q10 formulations". Mitochondrion 7 Suppl (Suppl): S78-88. June 2007. doi:10.1016/j.mito.2007.03.003. PMID 17482886.[verification needed]

- ↑ Westesen, K. & B. Siekmann, "Particles with modified physicochemical properties, their preparation and uses", US patent 6197349, published 2001

- ↑ Ohashi, H.; T. Takami & N. Koyama et al., "Aqueous solution containing ubidecarenone", US patent 4483873, published 1984

- ↑ "Relative bioavailability of two forms of a novel water-soluble coenzyme Q10". Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism 52 (4): 281–7. 2008. doi:10.1159/000129661. PMID 18645245.

- ↑ Kagan, Daniel; Madhavi, Doddabele (2010). "A Study on the Bioavailability of a Novel Sustained-Release Coenzyme Q10-β-Cyclodextrin Complex". Integrative Medicine 9 (1).

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 59.4 "Ubiquinone". Nature 182 (4652): 1764–7. December 1958. doi:10.1038/1821764a0. PMID 13622652. Bibcode: 1958Natur.182.1764M.

- ↑ "Isolation of a quinone from beef heart mitochondria". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 25 (1): 220–1. July 1957. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(57)90457-2. PMID 13445756.

- ↑ "Coenzyme Q. I. structure studies on the coenzyme Q group". Journal of the American Chemical Society 80 (17): 4752. 1958. doi:10.1021/ja01550a096. ISSN 0002-7863.

- ↑ "Quinones and quinols as inhibitors of lipid peroxidation". Lipids 1 (4): 282–4. July 1966. doi:10.1007/BF02531617. PMID 17805631.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 63.4 "Coenzyme Q10 contents in foods and fortification strategies". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 50 (4): 269–80. April 2010. doi:10.1080/10408390902773037. PMID 20301015.

- ↑ doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2011.03.018

- ↑ "The coenzyme Q10 content of the average Danish diet". International Journal for Vitamin and Nutrition Research. Internationale Zeitschrift für Vitamin- und Ernahrungsforschung. Journal International de Vitaminologie et de Nutrition 67 (2): 123–9. 1997. PMID 9129255.

External links

- "List of USP Verified CoQ10 Ingredients". U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention. http://www.usp.org/USPVerified/ingredients/ingredients.html.

- "Coenzyme Q10". National Cancer Institute. 23 September 2005. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/cam/coenzymeQ10/patient.

- Bonakdar, Robert Alan; Guarneri, Erminia (15 September 2005). "Coenzyme Q10". American Family Physician 72 (6): 1065–1070. PMID 16190504. http://www.aafp.org/afp/20050915/1065.html. Retrieved 13 November 2008.

|

KSF

KSF