Commercial classification of chemicals

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

Following the commercial classification of chemicals, chemicals produced by chemical industry can be divided essentially into three broad categories:

- commodity chemicals: are chemicals produced in large quantities and in general their applications can be traced back to their chemical structure; for this reason, two commodities produced by two different suppliers but with the same chemical structure and purity are almost identical and they can be easily interchanged; they are produced by continuous plant and in general their cost is relatively low; examples of chemical commodities are ammonia and ethylene oxide;[1]

- speciality chemicals (or specialty chemicals): are constituted by a mixture of different chemical substances, that is designed and produced in order to be applied to a specific application; the formulation of specialities is the result of scientific researches carried out by the producer company, so each formulation and associated properties are unique and for this reason in the majority of the cases it is not possible to easily interchange two different specialities produced by two different suppliers; examples of applications of speciality chemicals are pharmaceuticals industry and agriculture; they are produced by batch plant and in general their cost is higher if compared with commodity chemicals;[1]

- Fine chemicals: as the commodity chemicals, they are chemical substances characterized by their chemical structure, but, on the contrary of commodity chemicals, they are produced in a small quantity; fine chemicals can be used as components in the formulation of speciality chemicals;[2] for example active ingredients of pharmaceutical drugs are fine chemicals, but the pharmaceutical drug is a speciality chemical; examples of applications of fine chemicals are: pharmaceuticals industry, agriculture, photography chemicals and electronic chemicals;[3] they are produced by batch plant and in general their cost is relatively high.

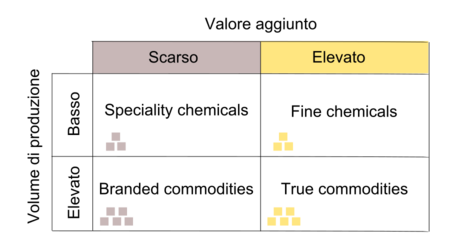

Kline matrix

Kline matrix was presented for the first time in 1970 by Charles Howard Kline.[5] It is a more detailed classification of the previous one, that distinguished chemical commodities into two subclasses, called respectively "true commodities" and "pseudocommodities". In general the classification of chemical industry products by the Kline matrix is related to the chemicals' worldwide production (measured for example in tons/year) and to their value added.[6]

Following this classification, the chemical industry products are divided into four categories:

- true commodity: high production and high value added

- fine chemical: low production and high value added

- pseudo-commodity (or branded commodity): high production and low value added

- speciality chemical: low production and low value added.

Basic chemicals

The concept of basic chemicals is very close to chemical commodities. In fact basic chemicals are chemical substances used as a starting material for the production of a wide variety of other chemicals; for this reason they are in general commodities, because they are highly demanded. Some examples of basic chemicals are: ethylene, benzene, chlorine and sulfuric acid.[7]

High production volume chemical

High Production Volume (HPV) Chemicals is another commercial classification of chemical substances very close to chemical commodities. This categories is used in United States of America and includes all the chemicals produced or imported by US in an amount higher than 1 million pounds.[8]

It is supposed that the number of commercialized chemical products is around 70,000 and around 5% of them are High production volume chemicals.[8]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Encyclopedia of chemical technology. 6: Chlorocarbons and chlorohydrocarbons-C2 to combustion technology (4. ed.- 1993 ed.). New York: Wiley. 1993. pp. 536. ISBN 978-0-471-52674-2.

- ↑ Pollak, Peter (2007). Fine chemicals: the industry and the business. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience. ISBN 978-0-470-05075-0.

- ↑ Mullin, Rick. "Fine Chemicals". pp. 41-49. http://pubs.acs.org/supplements/chemchronicles2/pdf/041.pdf.

- ↑ David J. Brennan, Process Industry Economics: An International Perspective, IChemE, 1998, pp. 14-16. ISBN 0852954611.

- ↑ "Charles H. Kline, 73, Chemical Consultant" (in en-US). The New York Times. 1992-04-28. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/04/28/obituaries/charles-h-kline-73-chemical-consultant.html.

- ↑ Emisawa Hiroshi, "How to Manage for Maximum Profit."

- ↑ (in Italian) http://scuole.federchimica.it/Universita/Schede_di_approfondimento_sui_settori/Chimica_di_base.aspx

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "High Production Volume (HPV) Chemicals". http://scorecard.goodguide.com/chemical-profiles/def/hpv.html.

See also

|

KSF

KSF