Copper compounds

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

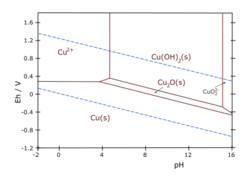

Copper forms a rich variety of compounds, usually with oxidation states +1 and +2, which are often called cuprous and cupric, respectively.[1] Copper compounds, whether organic complexes or organometallics, promote or catalyse numerous chemical and biological processes.[2]

Binary compounds

Cuprous halides with fluorine, chlorine, bromine, and iodine are known, as are cupric halides with fluorine, chlorine, and bromine. Attempts to prepare copper(II) iodide yield only copper(I) iodide and iodine.[1]

- 2 Cu2+ + 4 I− → 2 CuI + I2

Coordination chemistry

Cu–O and Cu–N complexes

Copper forms coordination complexes with ligands. In aqueous solution, copper(II) exists as [Cu(H2O)6]2+. This complex exhibits the fastest water exchange rate (speed of water ligands attaching and detaching) for any transition metal aquo complex. Adding aqueous sodium hydroxide causes the precipitation of light blue solid copper(II) hydroxide. A simplified equation is:

- Cu2+ + 2 OH− → Cu(OH)2

Aqueous ammonia results in the same precipitate. Upon adding excess ammonia, the precipitate dissolves, forming tetraamminecopper(II):

- Cu(H2O)4(OH)2 + 4 NH3 → [Cu(H2O)2(NH3)4]2+ + 2 H2O + 2 OH−

Many other oxyanions form complexes; these include copper(II) acetate, copper(II) nitrate, and copper(II) carbonate. Copper(II) sulfate forms a blue crystalline pentahydrate, the most familiar copper compound in the laboratory. It is used in a fungicide called the Bordeaux mixture.[3]

Polyols, compounds containing more than one alcohol functional group, generally interact with cupric salts. For example, copper salts are used to test for reducing sugars. Specifically, using Benedict's reagent and Fehling's solution the presence of the sugar is signaled by a color change from blue Cu(II) to reddish copper(I) oxide.[4] Schweizer's reagent and related complexes with ethylenediamine and other amines dissolve cellulose.[5] Amino acids such as cystine form very stable chelate complexes with copper(II).[6][7][8] Many wet-chemical tests for copper ions exist, one involving potassium ferrocyanide, which gives a brown precipitate with copper(II) salts.

Cu–X complexes

Copper also forms complexes with halides. In Cs2CuCl4, CuCl42− exhibits a distorted (flattened) tetrahedral geometry, whereas in [Pt(NH3)4][CuCl4], it adopts a planar configuration. Green CuBr3− and violet CuBr42− are also known.[9] Monovalent copper forms luminescent CunXn clusters (where X = Br, Cl, I), exhibiting diverse optical properties.[10][11]

Organocopper chemistry

Compounds that contain a carbon-copper bond are known as organocopper compounds. They are very reactive towards oxygen to form copper(I) oxide and have many uses in chemistry. They are synthesized by treating copper(I) compounds with Grignard reagents, terminal alkynes or organolithium reagents;[12] in particular, the last reaction described produces a Gilman reagent. These can undergo substitution with alkyl halides to form coupling products; as such, they are important in the field of organic synthesis. Copper(I) acetylide is highly shock-sensitive but is an intermediate in reactions such as the Cadiot-Chodkiewicz coupling[13] and the Sonogashira coupling.[14] Conjugate addition to enones[15] and carbocupration of alkynes[16] can also be achieved with organocopper compounds. Copper(I) forms a variety of weak complexes with alkenes and carbon monoxide, especially in the presence of amine ligands.[17]

Copper(III) and copper(IV)

Copper(III) is most often found in oxides. A simple example is potassium cuprate, KCuO2, a blue-black solid.[18] The most extensively studied copper(III) compounds are the cuprate superconductors. Yttrium barium copper oxide (YBa2Cu3O7) consists of both Cu(II) and Cu(III) centres. Like oxide, fluoride is a highly basic anion[19] and is known to stabilize metal ions in high oxidation states. Both copper(III) and even copper(IV) fluorides are known, K3CuF6 and Cs2CuF6, respectively.[1]

Some copper proteins form oxo complexes, which also feature copper(III).[20] With tetrapeptides, purple-colored copper(III) complexes are stabilized by the deprotonated amide ligands.[21]

Complexes of copper(III) are also found as intermediates in reactions of organocopper compounds.[22] For example, in the Kharasch–Sosnovsky reaction.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Holleman, A.F.; Wiberg, N. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ↑ Trammell, Rachel; Rajabimoghadam, Khashayar; Garcia-Bosch, Isaac (30 January 2019). "Copper-Promoted Functionalization of Organic Molecules: from Biologically Relevant Cu/O2 Model Systems to Organometallic Transformations". Chemical Reviews 119 (4): 2954–3031. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00368. PMID 30698952.

- ↑ Wiley-Vch (2 April 2007). "Nonsystematic (Contact) Fungicides". Ullmann's Agrochemicals. Wiley. p. 623. ISBN 978-3-527-31604-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=cItuoO9zSjkC&pg=PA623.

- ↑ Ralph L. Shriner, Christine K.F. Hermann, Terence C. Morrill, David Y. Curtin, Reynold C. Fuson "The Systematic Identification of Organic Compounds" 8th edition, J. Wiley, Hoboken. ISBN 0-471-21503-1

- ↑ Saalwächter, Kay; Burchard, Walther; Klüfers, Peter; Kettenbach, G.; Mayer, Peter; Klemm, Dieter; Dugarmaa, Saran (2000). "Cellulose Solutions in Water Containing Metal Complexes". Macromolecules 33 (11): 4094–4107. doi:10.1021/ma991893m. Bibcode: 2000MaMol..33.4094S.

- ↑ Deodhar, S., Huckaby, J., Delahoussaye, M. and DeCoster, M.A., 2014, August. High-aspect ratio bio-metallic nanocomposites for cellular interactions. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 64, No. 1, p. 012014). https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/64/1/012014/meta.

- ↑ Kelly, K.C., Wasserman, J.R., Deodhar, S., Huckaby, J. and DeCoster, M.A., 2015. Generation of scalable, metallic high-aspect ratio nanocomposites in a biological liquid medium. Journal of Visualized Experiments, (101), p.e52901. https://www.jove.com/t/52901/generation-scalable-metallic-high-aspect-ratio-nanocomposites.

- ↑ Karan, A., Darder, M., Kansakar, U., Norcross, Z. and DeCoster, M.A., 2018. Integration of a Copper-Containing Biohybrid (CuHARS) with Cellulose for Subsequent Degradation and Biomedical Control. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(5), p.844. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/15/5/844

- ↑ R.A. Howald; D.P. Keeton (1966). "Charge transfer spectra and structure of the copper (II) halide complexes". Spectrochimica Acta 22 (7): 1211–1222. doi:10.1016/0371-1951(66)80024-3. Bibcode: 1966AcSpe..22.1211H.

- ↑ Abraham Mensah; Juan-Juan Shao; Jian-Ling Ni; Guang-Jun Li; Fang-Ming Wang; Li-Zhuang Chen (2022). "Recent Progress in Luminescent Cu(I) Halide Complexes: A Mini-Review". Frontiers in Chemistry 9: 1127. doi:10.3389/fchem.2021.816363. PMID 35145957. Bibcode: 2022FrCh....9.1127W.

- ↑ Hiromi Araki, Kiyoshi Tsuge, Yoichi Sasaki, Shoji Ishizaka, and Noboru Kitamura (2005). "Luminescence Ranging from Red to Blue: A Series of Copper(I)−Halide Complexes Having Rhombic {Cu2(μ-X)2} (X = Br and I) Units with N-Heteroaromatic Ligands". Inorg. Chem. 44 (26): 9667–9675. doi:10.1021/ic0510359. PMID 16363835.

- ↑ "Modern Organocopper Chemistry" Norbert Krause, Ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2002. ISBN 978-3-527-29773-3.

- ↑ Berná, José; Goldup, Stephen; Lee, Ai-Lan; Leigh, David; Symes, Mark; Teobaldi, Gilberto; Zerbetto, Fransesco (26 May 2008). "Cadiot–Chodkiewicz Active Template Synthesis of Rotaxanes and Switchable Molecular Shuttles with Weak Intercomponent Interactions". Angewandte Chemie 120 (23): 4464–4468. doi:10.1002/ange.200800891. Bibcode: 2008AngCh.120.4464B.

- ↑ Rafael Chinchilla; Carmen Nájera (2007). "The Sonogashira Reaction: A Booming Methodology in Synthetic Organic Chemistry". Chemical Reviews 107 (3): 874–922. doi:10.1021/cr050992x. PMID 17305399.

- ↑ "An Addition of an Ethylcopper Complex to 1-Octyne: (E)-5-Ethyl-1,4-Undecadiene". Organic Syntheses 64: 1. 1986. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.064.0001.

- ↑ Kharasch, M.S.; Tawney, P.O. (1941). "Factors Determining the Course and Mechanisms of Grignard Reactions. II. The Effect of Metallic Compounds on the Reaction between Isophorone and Methylmagnesium Bromide". Journal of the American Chemical Society 63 (9): 2308–2316. doi:10.1021/ja01854a005. Bibcode: 1941JAChS..63.2308K.

- ↑ Imai, Sadako; Fujisawa, Kiyoshi; Kobayashi, Takako; Shirasawa, Nobuhiko; Fujii, Hiroshi; Yoshimura, Tetsuhiko; Kitajima, Nobumasa; Moro-oka, Yoshihiko (1998). "63Cu NMR Study of Copper(I) Carbonyl Complexes with Various Hydrotris(pyrazolyl)borates: Correlation between 63Cu Chemical Shifts and CO Stretching Vibrations". Inorganic Chemistry 37 (12): 3066–3070. doi:10.1021/ic970138r.

- ↑ G. Brauer, ed (1963). "Potassium Cuprate (III)". Handbook of Preparative Inorganic Chemistry. 1 (2nd ed.). NY: Academic Press. p. 1015.

- ↑ Schwesinger, Reinhard; Link, Reinhard; Wenzl, Peter; Kossek, Sebastian (2006). "Anhydrous phosphazenium fluorides as sources for extremely reactive fluoride ions in solution". Chemistry: A European Journal 12 (2): 438–45. doi:10.1002/chem.200500838. PMID 16196062. Bibcode: 2006ChEuJ..12..438S.

- ↑ Lewis, E.A.; Tolman, W.B. (2004). "Reactivity of Dioxygen-Copper Systems". Chemical Reviews 104 (2): 1047–1076. doi:10.1021/cr020633r. PMID 14871149.

- ↑ McDonald, M.R.; Fredericks, F.C.; Margerum, D.W. (1997). "Characterization of Copper(III)–Tetrapeptide Complexes with Histidine as the Third Residue". Inorganic Chemistry 36 (14): 3119–3124. doi:10.1021/ic9608713. PMID 11669966.

- ↑ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 1187. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

|

KSF

KSF