D-CON

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

| |

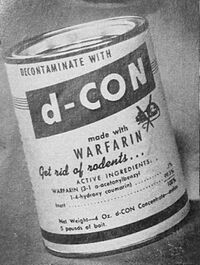

A d-CON can from 1950 | |

| Owner | Reckitt |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Introduced | 1950 |

| Previous owners |

|

| Tagline | "Get Out" "Mice Love It to Death" |

| Website | d-CONproducts.com |

d-CON is an American brand of rodent control products owned and distributed in the United States by the UK-based consumer goods company Reckitt, which includes traps and baits for use around the home for trapping and killing rats and mice. As of 2015, bait products use first-generation vitamin K anticoagulants as poison.

History

In 1950, the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation patented warfarin, a new chemical compound which had been in development since the 1930s.[1] Chicago businessman Lee Ratner secured a non-exclusive licensing agreement for the product, which had been approved for use as a rodenticide.[2][3] He then founded the d-CON Company to sell the new product, purchasing an initial supply from another company already distributing the compound.[4] (The name "d-CON" being a reference to "decontaminate".)[5] Within a short period of time, the product "revolutionized the art of rodent control".[1] Previously, farmers had to shoot rats one at a time or use high doses of toxic chemicals.[1][6] In contrast, warfarin posed minimal risk to other animals as cumulative doses were required to achieve toxicosis, and did not cause bait shyness.[1] d-CON was originally sold in 4-ounce packages of green powder for $2.98. When mixed with grain or ground meat the product produced six pounds of bait – enough to cover an average sized farm.[3][5]

Ratner hired four men to start the d-CON Company in the Summer of 1950. On September 5, a trial run of radio advertisements costing $1,000 was purchased.[5] For seven days, fifteen-minute infomercials ran on two radio stations – WIBW in Topeka and WLW in Cincinnati – during farm or news programs.[4][5] Mail order demand created by the ads was high and the following week the ads aired thrice daily on the stations. As demand remained high, more stations were added.[5] Print ads in farm papers followed.[3] By December, d-CON was spending $30,000 a week on coast-to-coast ads across 425 radio stations, and employed 60 people. According to company claims, d-CON was selling more rodent killer in a week than their nearest competitor sold in a year.[5] A month later, the company was up to 100 non-sales employees.[4]

To increase momentum for the new product, Ratner organized a 15-day experiment in Middleton, Wisconsin, a town with a particularly bad rat problem. On November 4, d-CON was distributed throughout the community free of charge. By November 19, the town's rat problem was under control with no traces of the rodents in the area.[5] Similar demonstrations throughout the country occurred twice a month.[3] Ratner secured endorsements of the U.S. Public Health Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services, and local authorities, as well as customer testimonials, all of which were featured in the company's ads. Radio advertising included segments in farm shows and sponsorship of popular general interest programs. d-CON's ad agency, Marfree Advertising, had to employ ten people to keep up with all the activity.[5]

Ratner continued the aggressive advertising campaign, turning to the relatively new medium of television.[6] McKesson & Robbins was contracted with for retail distribution.[5] At the peak of its advertising spending, d-CON had ads running on 475 television and radio stations, in every farm paper in the country, and in several major newspapers. On May 1, 1951, the company ceased mail-order distribution, having placed the product in more than 40,000 drug, grocery, and hardware stores.[3] Daytime ad buys were then expanded to support retail distribution to individual consumers.[4] Over the first eight months of its existence, d-CON had spent approximately $1 million on advertising, generating sales of $100,000 a week.[3] The company's rapid rise has been cited as a case study in effective mail-order advertising and called "as brilliant a record for a new product as you're likely to find anywhere, anytime."[7]

The success of d-CON led Ratner to expand the business, announcing plans to introduce 10 to 12 household products as subsidiaries of d-CON over the next several years. The first such product was an insecticide called Fli-Pel.[4] Although, d-CON itself became a retail-only product, the company continued aggressive mail-order sales for several years through subsidiaries such as the Grant Tool Company, Auto Grant, M-O-Lene, and Sona. In 1954, Ratner was spending more than $1 million a year on 10-minute infomercials across 300 TV stations, making the d-CON Company the nation's largest spender on mail-order TV ads. Products marketed in this manner included cleaning supplies, cosmetics, household tools, and a "rocket ignition device" for automobiles.[8] A 1955, eleven-week-long campaign costing $480,000 was described as the company's largest ever campaign by Alvin Eicoff, d-CON's vice president of advertising. The campaign consisted of a mix of 1 minute spots and 5 minute "special service" programs across 382 radio stations and a handful of TV stations. Simultaneous, a $180,000 mostly television campaign supported M-O-Lene Dry Cleaning products, and approximately $40,000 was being spent weekly on Grant Company mail-order products.[9]

In 1956, Ratner sold the d-CON brand for approximately $7 million to household product manufacturer Lehn & Fink, retaining the subsidiaries under the name The Grant Company.[2][10] In June 1966, Lehn & Fink was acquired by Sterling Drug in an all-stock merger. Subsequently, Lehn & Fink continued to operate as the household division of Sterling Drug.[11]

In the mid-1970s, warfarin resistance began to appear in mice, which prompted a need for alternative rodenticides.[12] This led to the introduction of brodifacoum in 1975, followed by d-CON's introduction of it in the commercial market in the 1980s.[13] The compound works similarly to warfarin, but requires fewer doses. Additionally, it causes an unquenchable thirst, causing rats to leave the home in search of water before dying.[14]

In 1994, Reckitt Benckiser (RB) bought Sterling Drug. In 2008, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decided to remove second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides (such as brodifacoum) from retail store shelves, listing secondary poisoning to wildlife that feeds on rats as the primary reason for action.[15][16] Accidental poisoning of pets and children was also a concern (as the case of a dog named Shania, a patient of Dr. Greg Martinez, demonstrated[17]), but a less serious one due to the effectiveness of Vitamin K as an antidote.[16] The ruling, which was slated to go into effect in 2011, applied only to retail consumers, not commercial use or agriculture.[15]

In 2011, RB initiated a legal challenge to the EPA ruling, saying alternatives were either less effective or more dangerous than brodifacoum. In 2013, the EPA passed a separate rule requiring rodent control products sold to consumers be in tamper-resistant bait stations, threatening to ban 12 d-CON products.[18] Early in 2014, California State Department of Pesticide Regulation ruled that anticoagulant rat poison sales would be restricted beginning on July 1, 2014. A suit was also filed to by RB to block the decision.[19]

In June 2014, Reckitt Benckiser and the EPA came to an agreement to end legal action. RB agreed to stop manufacturing twelve products with loose pellets or powder by the end of 2014, with distribution to retailers ending no later than March 31, 2015.[18] Retailers could continue to sell existing stock indefinitely.[16] Eight of the twelve products contained second-generation anticoagulants (brodifacoum or difethialone), which the company agreed not to use in its replacement products.[18]

Products

As of 2014, d-CON is the best selling rat poison in the United States.[16] The d-CON product line consists of traps, bait packets, and bait stations. Most products are marketed towards individual consumers for control of house mice.[20]

Ingredients

Prior to 2015, d-CON primarily used two active ingredients in the bait products. In the rat bait pellets, mouse bait pellets, place packs, and wedge baits, the active ingredient was brodifacoum, typically at 0.005% concentration.[21] In contrast, earlier d-CON products that used warfarin had 0.5% concentration.[5] In the refillable and disposable bait stations, the active ingredient was diphacinone.[22] The use of brodifacoum was discontinued at the end of 2014 following an agreement with the EPA, and was replaced with less potent first-generation vitamin K anticoagulants such as diphacinone.[15] As of 2019 the active ingredient in all bait stations has been changed to cholecalciferol.[23]

Ad strategy

The initial 1950's ad pitch emphasized the following points: rats do a large amount of damage to crops each year ("$22 a year per rat"); d-CON poses minimal risk to other animals; the product is undetectable (odorless and tasteless) by rats and does not produce bait shyness; and, the product was successfully tested in Middleton, Wisconsin. Additionally, consumers were promised discretion: the product was mailed in a "plain, unmarked wrapper".[4]

The ads, and in particular the reference to the Middleton experiment, convinced most farmers to buy only d-CON and not a cheaper warfarin competitor, according to reports by retailers who stocked multiple brands.[4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Link KP (January 1, 1959). "The discovery of dicumarol and its sequels". Circulation 19 (1): 97–107. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.19.1.97. PMID 13619027. http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/reprint/19/1/97.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Carla Ulakovic (2014). "Leonard Lee Ratner and Lucky Lee Ranch". Lehigh Acres. Carla Ulakovic. pp. 19–26. ISBN 9781467112079.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 "Mail-order Ads Power New product Into Big Seller". Printers' Ink 235: 40. 1951.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "America's Pied Piper". Sponsor 5 (1): 24–25; 44–46. January 1, 1951. https://archive.org/details/sponsor51spon.

- ↑ 5.00 5.01 5.02 5.03 5.04 5.05 5.06 5.07 5.08 5.09 "They Built a Better Mousetrap ... And Used Radio to Sell It". Broadcasting Telecasting: 22–3. December 11, 1950. http://americanradiohistory.com/Archive-BC/BC-1950/BC-1950-12-11.pdf.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Jules Freeman; Neil D. Freeman (2004). Become a Multi Millionaire in 5 Easy Lessons. Trafford Publishing. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-1412015790.

- ↑ William B. Ward (1952). Reporting Agriculture. Cornell University Press. pp. 326–7.

- ↑ "The Pitchmen in the Parlor". Broadcasting Telecasting: 81. August 9, 1954. https://archive.org/details/broadcastingtele47unse.

- ↑ "Grant Chemical, d-CON plan use of Radio-TV". Broadcasting Telecasting: 195. September 19, 1955. http://americanradiohistory.com/Archive-BC/BC-1955/1955-09-19-BC.pdf.

- ↑ Federal Communications Commission Reports. 2. 5. 1966. pp. 921–6; 946–52.

- ↑ Federal Trade Commission Decisions. 80. US Federal Trade Commission. 1972. pp. 479–480. https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/commission_decision_volumes/volume-80/ftc_volume_decision_80_january_-_june_1972pages_477-607.pdf.

- ↑ Adrian P. Meehan (December 1980). "The rodenticidal activity of reserpine and related compounds". Pesticide Science 11 (6): 555–561. doi:10.1002/ps.2780110602.

- ↑ "Brodifacoum". Toxnet. NIH. http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search/a?dbs+hsdb:@term+@DOCNO+3916. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ↑ Brendan Koerner (January 27, 2005). "Can Mouse Poison Kill You?". Slate. http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/explainer/2005/01/can_mouse_poison_kill_you.html. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Edie Lau (October 16, 2014). "Changes coming to common rodent poison". VIN News Service. http://news.vin.com/VINNews.aspx?articleId=34234. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Serena Ng; Alicia Mundy (May 30, 2014). "Rat Poison D-Con to Lose Some of Its Punch". Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/rat-poison-d-con-to-lose-some-of-its-punch-1401483224. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ↑ Martinez, DVM, Greg (April 11, 2007). "Dog Breathing Hard and Coughing Up Blood: D-con Poisoning" (in English) (YouTube video). United States: Greg Martinez DVM. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nUlW5W9rPRM. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Britt E. Erickson (June 5, 2014). "Maker Of Rat Poison d-CON To Pull Products". Chemical & Engineering News 92 (23): 10. doi:10.1021/cen-09223-notw6. http://cen.acs.org/articles/92/i23/Maker-Rat-Poison-d-CON.html. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Makers of rat poison d-Con sue California". mercurynews.com. March 31, 2014. http://www.mercurynews.com/business/ci_25461592/makers-rat-poison-d-con-sue-state. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- ↑ "d-CON Products". d-CON. http://www.d-conproducts.com/products/. Retrieved April 1, 2015.

- ↑ Small Animal Toxicoses - Rodenticides. VSPN.org. April 29, 2014. http://www.vspn.org/Library/misc/VSPN_M01287.htm. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ↑ "d-CON Bait Station". Reckitt Benckiser. http://www.rbnainfo.com/productpro/ProductSearch.do?brandId=10&productLineId=1420&searchType=PL&template=1. Retrieved April 2, 2015.

- ↑ "d-CON FAQ". Reckitt Benckiser. https://www.d-conproducts.com/faq/d-conreg-baits/#faq-3. Retrieved October 15, 2019.

External links

|

KSF

KSF