Estrogen (medication)

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 45 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 45 min

| Estrogen (medication) | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

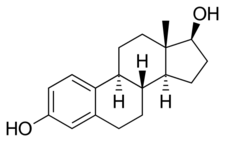

Estradiol, the major estrogen sex hormone in humans and a widely used medication. | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Contraception, menopause, hypogonadism, transgender women, prostate cancer, breast cancer, others |

| ATC code | G03C |

| Biological target | Estrogen receptors (ERα, ERβ, mERs (e.g., GPER, others)) |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D004967 |

An estrogen (E) is a type of medication which is used most commonly in hormonal birth control and menopausal hormone therapy, and as part of feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women.[1] They can also be used in the treatment of hormone-sensitive cancers like breast cancer and prostate cancer and for various other indications. Estrogens are used alone or in combination with progestogens.[1] They are available in a wide variety of formulations and for use by many different routes of administration.[1] Examples of estrogens include bioidentical estradiol, natural conjugated estrogens, synthetic steroidal estrogens like ethinylestradiol, and synthetic nonsteroidal estrogens like diethylstilbestrol.[1] Estrogens are one of three types of sex hormone agonists, the others being androgens/anabolic steroids like testosterone and progestogens like progesterone.

Side effects of estrogens include breast tenderness, breast enlargement, headache, nausea, fluid retention, and edema among others.[1] Other side effects of estrogens include an increased risk of blood clots, cardiovascular disease, and, when combined with most progestogens, breast cancer.[1] In men, estrogens can cause breast development, feminization, infertility, low testosterone levels, and sexual dysfunction among others.

Estrogens are agonists of the estrogen receptors, the biological targets of endogenous estrogens like estradiol. They have important effects in many tissues in the body, including in the female reproductive system (uterus, vagina, and ovaries), the breasts, bone, fat, the liver, and the brain among others.[1] Unlike other medications like progestins and anabolic steroids, estrogens do not have other hormonal activities.[1] Estrogens also have antigonadotropic effects and at sufficiently high dosages can strongly suppress sex hormone production.[1] Estrogens mediate their contraceptive effects in combination with progestins by inhibiting ovulation.

Estrogens were first introduced for medical use in the early 1930s. They started to be used in birth control in combination with progestins in the 1950s.[2] A variety of different estrogens have been marketed for clinical use in humans or use in veterinary medicine, although only a handful of these are widely used.[3][4][5][6][7] These medications can be grouped into different types based on origin and chemical structure.[1] Estrogens are available widely throughout the world and are used in most forms of hormonal birth control and in all menopausal hormone therapy regimens.[3][4][6][5][1]

Medical uses

Birth control

Estrogens have contraceptive effects and are used in combination with progestins (synthetic progestogens) in birth control to prevent pregnancy in women. This is referred to as combined hormonal contraception. The contraceptive effects of estrogens are mediated by their antigonadotropic effects and hence by inhibition of ovulation. Most combined oral contraceptives contain ethinylestradiol or its prodrug mestranol as the estrogen component, but a few contain estradiol or estradiol valerate. Ethinylestradiol is generally used in oral contraceptives instead of estradiol because it has superior oral pharmacokinetics (higher bioavailability and less interindividual variability) and controls vaginal bleeding more effectively. This is due to its synthetic nature and its resistance to metabolism in certain tissues such as the intestines, liver, and uterus relative to estradiol. Besides oral contraceptives, other forms of combined hormonal contraception include contraceptive patches, contraceptive vaginal rings, and combined injectable contraceptives. Contraceptive patches and vaginal rings contain ethinylestradiol as the estrogen component, while combined injectable contraceptives contain estradiol or more typically an estradiol ester.

Hormone therapy

Menopause

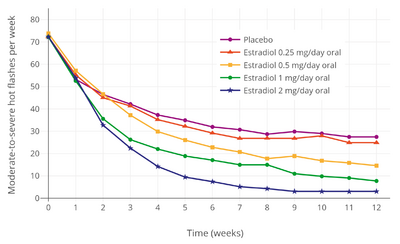

Estrogen and other hormones are given to postmenopausal women in order to prevent osteoporosis as well as treat the symptoms of menopause such as hot flashes, vaginal dryness, urinary stress incontinence, chilly sensations, dizziness, fatigue, irritability, and sweating. Fractures of the spine, wrist, and hips decrease by 50 to 70% and spinal bone density increases by approximately 5% in those women treated with estrogen within 3 years of the onset of menopause and for 5 to 10 years thereafter.

Before the specific dangers of conjugated estrogens were well understood, standard therapy was 0.625 mg/day of conjugated estrogens (such as Premarin). There are, however, risks associated with conjugated estrogen therapy. Among the older postmenopausal women studied as part of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), an orally administered conjugated estrogen supplement was found to be associated with an increased risk of dangerous blood clotting. The WHI studies used one type of estrogen supplement, a high oral dose of conjugated estrogens (Premarin alone and with medroxyprogesterone acetate as Prempro).[10]

In a study by the NIH, esterified estrogens were not proven to pose the same risks to health as conjugated estrogens. Menopausal hormone therapy has favorable effects on serum cholesterol levels, and when initiated immediately upon menopause may reduce the incidence of cardiovascular disease, although this hypothesis has yet to be tested in randomized trials. Estrogen appears to have a protector effect on atherosclerosis: it lowers LDL and triglycerides, it raises HDL levels and has endothelial vasodilatation properties plus an anti-inflammatory component.

Research is underway to determine if risks of estrogen supplement use are the same for all methods of delivery. In particular, estrogen applied topically may have a different spectrum of side effects than when administered orally,[11] and transdermal estrogens do not affect clotting as they are absorbed directly into the systemic circulation, avoiding first-pass metabolism in the liver. This route of administration is thus preferred in women with a history of thromboembolic disease.

Estrogen is also used in the therapy of vaginal atrophy, hypoestrogenism (as a result of hypogonadism, oophorectomy, or primary ovarian failure), amenorrhea, dysmenorrhea, and oligomenorrhea. Estrogens can also be used to suppress lactation after child birth.

Synthetic estrogens, such as 17α-substituted estrogens like ethinylestradiol and its C3 esters and ethers mestranol, quinestrol, and ethinylestradiol sulfonate, and nonsteroidal estrogens like the stilbestrols diethylstilbestrol, hexestrol, and dienestrol, are no longer used in menopausal hormone therapy, owing to their disproportionate effects on liver protein synthesis and associated health risks.[12]

Hypogonadism

Estrogens are used along with progestogens to treat hypogonadism and delayed puberty in women.

Transgender women

Estrogens are used along with antiandrogens and progestogens as a component of feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women and other transfeminine individuals.[13][14][15]

Hormonal cancer

Prostate cancer

High-dose estrogen therapy with a variety of estrogens such as diethylstilbestrol, ethinylestradiol, polyestradiol phosphate, estradiol undecylate, estradiol valerate, and estradiol has been used to treat prostate cancer in men.[16] It is effective because estrogens are functional antiandrogens, capable of suppressing testosterone levels to castrate concentrations and decreasing free testosterone levels by increasing sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) production. High-dose estrogen therapy is associated with poor tolerability and safety, namely gynecomastia and cardiovascular complications such as thrombosis.[additional citation(s) needed] For this reason, has largely been replaced by newer antiandrogens such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and nonsteroidal antiandrogens. It is still sometimes used in the treatment of prostate cancer however,[16] and newer estrogens with atypical profiles such as GTx-758 that have improved tolerability profiles are being studied for possible application in prostate cancer.

Breast cancer

High-dose estrogen therapy with potent synthetic estrogens such as diethylstilbestrol and ethinylestradiol was used in the past in the palliation treatment of breast cancer.[17] Its effectiveness is approximately equivalent to that of antiestrogen therapy with selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) like tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors like anastrozole.[17] The use of high-dose estrogen therapy in breast cancer has mostly been superseded by antiestrogen therapy due to the improved safety profile of the latter.[17] High-dose estrogen therapy was the standard of care for the palliative treatment of breast cancer in women up to the late 1970s or early 1980s.[18]

Other uses

Infertility

Estrogens may be used in treatment of infertility in women when there is a need to develop sperm-friendly cervical mucous or an appropriate uterine lining.[19][20]

Pregnancy support

Estrogens like diethylstilbestrol were formerly used in high doses to help support pregnancy.[21] However, subsequent research showed diethylstilbestrol to be ineffective as well as harmful.[21]

Lactation suppression

Estrogens can be used to suppress lactation, for instance in the treatment of breast engorgement or galactorrhea.[22] However, high doses are needed, the effectiveness is uncertain, and high doses of estrogens in the postpartum period can increase the risk of blood clots.[23]

Tall stature

Estrogen has been used to induce growth attenuation in tall girls.[24]

Estrogen-induced growth attenuation was used as part of the controversial Ashley Treatment to keep a developmentally disabled girl from growing to adult size.[25]

Acromegaly

Estrogens have been used to treat acromegaly.[26][27][28] This is because they suppress growth hormone-induced insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) production in the liver.[26][27][28]

Sexual deviance

High-dose estrogen therapy has been used successfully in the treatment of sexual deviance such as paraphilias in men.[29][30] However, it has been found to produce many side effects (e.g., gynecomastia, feminization, cardiovascular disease, blood clots), and so is no longer recommended for such purposes.[29] High-dose estrogen therapy works by suppressing testosterone levels, similarly to high-dose progestogen therapy and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) modulator therapy.[29] Lower dosages of estrogens have also been used in combination with high-dose progestogen therapy in the treatment of sexual deviance in men.[29] High incidence of sexual dysfunction has similarly been associated with high-dose estrogen therapy in men treated with it for prostate cancer.[31]

Breast enhancement

Estrogens are involved in breast development and may be used as a form of hormonal breast enhancement to increase the size of the breasts.[32][33][34][35][36] However, acute or temporary breast enlargement is a well-known side effect of estrogens, and increases in breast size tend to regress following discontinuation of treatment.[32][34][35] Aside from those without prior established breast development, evidence is lacking for a sustained increase in breast size with estrogens.[32][34][35]

Depression

Published 2019 and 2020 guidelines from the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) and European Menopause and Andropause Society (EMAS) have reviewed the topic of estrogen therapy for depressive symptoms in the peri- and postmenopause.[37][38] There is some evidence that estrogens are effective in the treatment of depression in perimenopausal women.[37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47] The magnitude of benefit appears to be similar to that of classical antidepressants.[37][38] There is also some evidence that estrogens may improve mood and well-being in non-depressed perimenopausal women.[37][38][42][40] Estrogens do not appear to be effective in the treatment of depression in postmenopausal women.[37][38] This suggests that there is a window of opportunity for effective treatment of depressive symptoms with estrogens.[37] Research on combined estrogen and progestogen therapy for depressive symptoms in the peri- and postmenopause is scarce and inconclusive.[37][38] Estrogens may augment the mood benefits of antidepressants in middle-aged and older women.[37][38] Menopausal hormone therapy is not currently approved for the treatment of depressive symptoms in the peri- or postmenopause in either the United States or the United Kingdom due to insufficient evidence of effectiveness.[37][38][42] More research is needed on the issue of estrogen therapy for depressive symptoms associated with menopause.[45][43]

Schizophrenia

Estrogens appear to be useful in the treatment of schizophrenia in both women and men.[48][49][50][51]

Acne

Systemic estrogen therapy at adequate doses is effective for and has been used in the treatment of acne in both females and males, but causes major side effects such as feminization and gynecomastia in males.[52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59]

Available forms

| Generic name | Class | Brand name | Route | Intr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conjugated estrogens | S/ester[lower-alpha 1] | Premarin | PO, IM, TD, V | 1941 |

| Dienestrol[lower-alpha 2] | NS | Synestrol[lower-alpha 3] | PO | 1947 |

| Diethylstilbestrol[lower-alpha 2] | NS | Stilbestrol[lower-alpha 3] | PO, TD, V | 1939 |

| Esterified estrogens | NS/ester[lower-alpha 1] | Estratab | PO | 1970 |

| Estetrol[lower-alpha 4] | S | Donesta[lower-alpha 3] | PO | N/A |

| Estradiol | S | Estrace[lower-alpha 3] | PO, IM, SC, SL, TD, V | 1935 |

| Estradiol acetate | S/ester | Femring[lower-alpha 3] | PO, V | 2001 |

| Estradiol benzoate | S/ester | Progynon B | IM | 1933 |

| Estradiol cypionate | S/ester | Depo-Estradiol | IM | 1952 |

| Estradiol enanthate | S/ester | Deladroxate[lower-alpha 3] | IM | 1970s |

| Estradiol valerate | S/ester | Progynon Depot[lower-alpha 3] | PO, IM | 1954 |

| Estramustine phosphate[lower-alpha 5] | S/ester | Emcyt[lower-alpha 3] | PO | 1970s |

| Estriol | S | Theelol[lower-alpha 3] | PO, V | 1930 |

| Estropipate[lower-alpha 2] | S/ester | Ogen | PO | 1968 |

| Ethinylestradiol | S/alkyl | Estinyl[lower-alpha 3] | PO, TD, V | 1943 |

| Fosfestrol[lower-alpha 2] | NS/ester | Honvan[lower-alpha 3] | IM | 1947 |

| Hexestrol[lower-alpha 2] | NS | Synestrol[lower-alpha 3] | PO, IM | 1940s |

| Mestranol[lower-alpha 2] | S/alkyl/ether | Enovid[lower-alpha 3] | PO | 1957 |

| Methylestradiol[lower-alpha 2] | S/alkyl | Ginecosid[lower-alpha 3] | PO | 1955 |

| Polyestradiol phosphate[lower-alpha 2] | S/ester | Estradurin | IM | 1957 |

| Prasterone[lower-alpha 6] | Prohormone | Intrarosa[lower-alpha 3] | PO, IM, V | 1970s |

| Zeranol[lower-alpha 7] | NS | Ralgro[lower-alpha 3] | PO | 1970s |

| ||||

Estrogens that have been marketed come in two major types, steroidal estrogens and nonsteroidal estrogens.[1][60]

Steroidal estrogens

Estradiol, estrone, and estriol have all been approved as pharmaceutical drugs and are used medically.[1] Estetrol is currently under development for medical indications, but has not yet been approved in any country.[61] A variety of synthetic estrogen esters, such as estradiol valerate, estradiol cypionate, estradiol acetate, estradiol benzoate, estradiol undecylate, and polyestradiol phosphate, are used clinically.[1] The aforementioned compounds behave as prodrugs to estradiol, and are much longer-lasting in comparison when administered by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection.[1] Esters of estrone and estriol also exist and are or have been used in clinical medicine, for example estrone sulfate (e.g., as estropipate), estriol succinate, and estriol glucuronide (as Emmenin and Progynon).[1]

Ethinylestradiol is a more potent synthetic analogue of estradiol that is used widely in hormonal contraceptives.[1] Other synthetic derivatives of estradiol related to ethinylestradiol that are used clinically include mestranol, quinestrol, ethinylestradiol sulfonate, moxestrol, and methylestradiol. Conjugated estrogens (brand name Premarin), an estrogen product manufactured from the urine of pregnant mares and commonly used in menopausal hormone therapy, is a mixture of natural estrogens including estrone sulfate and equine estrogens such as equilin sulfate and 17β-dihydroequilin sulfate.[1] A related and very similar product to conjugated estrogens, differing from it only in composition, is esterified estrogens.[1]

Testosterone, prasterone (dehydroepiandrosterone; DHEA), boldenone (δ1-testosterone), and nandrolone (19-nortestosterone) are naturally occurring androgens/anabolic steroids (AAS) which form estradiol as an active metabolite in small amounts and can produce estrogenic effects, most notably gynecomastia in men at sufficiently high dosages.[62] Similarly, a number of synthetic AAS, including methyltestosterone, metandienone, normethandrone, and norethandrolone, produce methylestradiol or ethylestradiol as an active metabolite in small quantities, and can produce estrogenic effects as well.[62] A few progestins, specifically the 19-nortestosterone derivatives norethisterone, noretynodrel, and tibolone, metabolize into estrogens (e.g., ethinylestradiol) and can produce estrogenic effects as well.[1][63]

Nonsteroidal estrogens

Diethylstilbestrol is a nonsteroidal estrogen that is no longer used medically. It is a member of the stilbestrol group. Other stilbestrol estrogens that have been used clinically include benzestrol, dienestrol, dienestrol acetate, diethylstilbestrol dipropionate, fosfestrol, hexestrol, and methestrol dipropionate. Chlorotrianisene, methallenestril, and doisynoestrol are nonsteroidal estrogens structurally distinct from the stilbestrols that have also been used clinically. While used widely in the past, nonsteroidal estrogens have mostly been discontinued and are now rarely if ever used medically.

Contraindications

Estrogens have various contraindications.[64][65][66][67] An example is history of thromboembolism (blood clots).[64][65][66][67]

Side effects

The most common side effects of estrogens in general include breast tenderness, breast enlargement, headache, nausea, fluid retention, and edema. In women, estrogens can additionally cause vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, and anovulation, whereas in men, estrogens can additionally cause gynecomastia (male breast development), feminization, demasculinization, sexual dysfunction (reduced libido and erectile dysfunction), hypogonadism, testicular atrophy, and infertility.

Estrogens can or may increase the risk of uncommon or rare but potentially serious issues including endometrial hyperplasia, endometrial cancer, cardiovascular complications (e.g., blood clots, stroke, heart attack), cholestatic hepatotoxicity, gallbladder disease (e.g., gallstones), hyperprolactinemia, prolactinoma, and dementia. These adverse effects are moderated by the concomitant use of a progestogen, the type of progestogen used, and the dosage and route of estrogen used.

Around half of women with epilepsy who menstruate have a lowered seizure threshold around ovulation, most likely from the heightened estrogen levels at that time. This results in an increased risk of seizures in these women.

High doses of synthetic estrogens like ethinylestradiol and diethylstilbestrol can produce prominent untoward side effects like nausea, vomiting, headache, malaise, and dizziness, among others.[68][69][70] Conversely, natural estrogens like estradiol and conjugated estrogens are rarely associated with such effects.[68][69][70] The preceding side effects of synthetic estrogens do not appear to occur in pregnant women, who already have very high estrogen levels.[68] This suggests that these effects are due to estrogenic activity.[68] Synthetic estrogens have markedly stronger effects on the liver and hepatic protein synthesis than natural estrogens.[1][71][72][70][73] This is related to the fact that synthetic estrogens like ethinylestradiol are much more resistant to metabolism in the liver than natural estrogens.[1][74][73]

Long-term effects

Endometrial hyperplasia and cancer

Unopposed estrogen therapy stimulates the growth of the endometrium and is associated with a dramatically increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer in postmenopausal women.[75] The risk of endometrial hyperplasia is greatly increased by 6 months of treatment (OR = 5.4) and further increased after 36 months of treatment (OR = 16.0).[75] This can eventually progress to endometrial cancer, and the risk of endometrial cancer similarly increases with duration of treatment (less than one year, RR = 1.4; many years (e.g., more than 10 years), RR = 15.0).[75] The risk of endometrial cancer also stays significantly elevated many years after stopping unopposed estrogen therapy, even after 15 years or more (RR = 5.8).[75]

Progestogens prevent the effects of estrogens on the endometrium.[75] As a result, they are able to completely block the increase in risk of endometrial hyperplasia caused by estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women, and are even able to decrease it below baseline (OR = 0.3 with continuous estrogen–progestogen therapy).[75] Continuous estrogen–progestogen therapy is more protective than sequential therapy, and a longer duration of treatment with continuous therapy is also more protective.[75] The increase in risk of endometrial cancer is similarly decreased with continuous estrogen–progestogen therapy (RR = 0.2–0.7).[75] For these reasons, progestogens are always used alongside estrogens in women who have intact uteruses.[75]

Cardiovascular events

Estrogens affect liver protein synthesis and thereby influence the cardiovascular system.[1] They have been found to affect the production of a variety of coagulation and fibrinolytic factors, including increased factor IX, von Willebrand factor, thrombin–antithrombin complex (TAT), fragment 1+2, and D-dimer and decreased fibrinogen, factor VII, antithrombin, protein S, protein C, tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1).[1] Although this is true for oral estrogen, transdermal estradiol has been found only to reduce PAI-1 and protein S, and to a lesser extent than oral estrogen.[1] Due to its effects on liver protein synthesis, oral estrogen is procoagulant, and has been found to increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), including of both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE).[1] Conversely, modern oral contraceptives are not associated with an increase in the risk of stroke and myocardial infarction (heart attack) in healthy, non-smoking premenopausal women of any age, except in those with hypertension (high blood pressure).[76][77] However, a small but significant increase in the risk of stroke, though not of myocardial infarction, has been found in menopausal women taking hormone replacement therapy.[78] An increase in the risk of stroke has also been associated with older high-dose oral contraceptives that are no longer used.[79]

Menopausal hormone therapy with replacement dosages of estrogens and progestogens has been associated with a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events such as VTE.[80][81] However, such risks have been found to vary depending on the type of estrogen and the route of administration.[80][81] The risk of VTE is increased by approximately 2-fold in women taking oral estrogen for menopausal hormone therapy.[80][81] However, clinical research to date has generally not distinguished between conjugated estrogens and estradiol.[81] This is of importance because conjugated estrogens have been found to be more resistant to hepatic metabolism than estradiol and to increase clotting factors to a greater extent.[1] Only a few clinical studies have compared oral conjugated estrogens and oral estradiol.[81] Oral conjugated estrogens have been found to possess a significantly greater risk of thromboembolic and cardiovascular complications than oral estradiol (OR = 2.08) and oral esterified estrogens (OR = 1.78).[81][82][83] However, in another study, the increase in VTE risk with 0.625 mg/day oral conjugated estrogens plus medroxyprogesterone acetate and 1 or 2 mg/day oral estradiol plus norethisterone acetate was found to be equivalent (RR = 4.0 and 3.9, respectively).[84][85] Other studies have found oral estradiol to be associated with an increase in risk of VTE similarly (RR = 3.5 in one, OR = 3.54 in first year of use in another).[81][86] As of present, there are no randomized controlled trials comparing oral conjugated estrogens and oral estradiol in terms of thromboembolic and cardiovascular risks that would allow for unambiguous conclusions, and additional research is needed to clarify this issue.[81][80] In contrast to oral estrogens as a group, transdermal estradiol at typical menopausal replacement dosages has not been found to increase the risk of VTE or other cardiovascular events.[80][78][81]

Both combined birth control pills (which contain ethinylestradiol and a progestin) and pregnancy are associated with about a 4-fold increase in risk of VTE, with the risk increase being slightly greater with the latter (OR = 4.03 and 4.24, respectively).[87] The risk of VTE during the postpartum period is 5-fold higher than during pregnancy.[87] Other research has found that the rate of VTE is 1 to 5 in 10,000 woman-years in women who are not pregnant or taking a birth control pill, 3 to 9 in 10,000 woman-years in women who are on a birth control pill, 5 to 20 in 10,000 women-years in pregnant women, and 40 to 65 in 10,000 women-years in postpartum women.[88] For birth control pills, VTE risk with high doses of ethinylestradiol (>50 μg, e.g., 100 to 150 μg) has been reported to be approximately twice that of low doses of ethinylestradiol (e.g., 20 to 50 μg).[76] As such, high doses of ethinylestradiol are no longer used in combined oral contraceptives, and all modern combined oral contraceptives contain 50 μg ethinylestradiol or less.[89][90] The absolute risk of VTE in pregnancy is about 0.5 to 2 in 1,000 (0.125%).[91]

Aside from type of estrogen and the route of administration, the risk of VTE with oral estrogen is also moderated by other factors, including the concomitant use of a progestogen, dosage, age, and smoking.[92][85] The combination of oral estrogen and a progestogen has been found to double the risk of VTE relative to oral estrogen alone (RR = 2.05 for estrogen monotherapy, and RR = 2.02 for combined estrogen–progestogen therapy in comparison).[92] However, while this is true for most progestogens, there appears to be no increase in VTE risk relative to oral estrogen alone with the addition of oral progesterone or the atypical progestin dydrogesterone.[92][93][94] The dosage of oral estrogen appears to be important for VTE risk, as 1 mg/day oral estradiol increased VTE incidence by 2.2-fold while 2 mg/day oral estradiol increased VTE incidence by 4.5-fold (both in combination with norethisterone acetate).[85] The risk of VTE and other cardiovascular complications with oral estrogen–progestogen therapy increases dramatically with age.[92] In the oral conjugated estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate arm of the WHI, the risks of VTE stratified by age were as follows: age 50 to 59, RR = 2.27; age 60 to 69, RR = 4.28; and age 70 to 79, RR = 7.46.[92] Conversely, in the oral conjugated estrogens monotherapy arm of the WHI, the risk of VTE increased with age similarly but was much lower: age 50 to 59, RR = 1.22; age 60 to 69, RR = 1.3; and age 70 to 79, RR = 1.44.[92] In addition to menopausal hormone therapy, cardiovascular mortality has been found to increase considerably with age in women taking ethinylestradiol-containing combined oral contraceptives and in pregnant women.[95][96] In addition, smoking has been found to exponentially increase cardiovascular mortality in conjunction with combined oral contraceptive use and older age.[95][96] Whereas the risk of cardiovascular death is 0.06 per 100,000 in women who are age 15 to 34 years, are taking a combined oral contraceptive, and do not smoke, this increases by 50-fold to 3.0 per 100,000 in women who are age 35 to 44 years, are taking a combined oral contraceptive, and do not smoke.[95][96] Moreover, in women who do smoke, the risk of cardiovascular death in these two groups increases to 1.73 per 100,000 (29-fold higher relative to non-smokers) and 19.4 per 100,000 (6.5-fold higher relative to non-smokers), respectively.[95][96]

Although estrogens influence the hepatic production of coagulant and fibrinolytic factors and increase the risk of VTE and sometimes stroke, they also influence the liver synthesis of blood lipids and can have beneficial effects on the cardiovascular system.[1] With oral estradiol, there are increases in circulating triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein A1, and apolipoprotein A2, and decreases in total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, apolipoprotein B, and lipoprotein(a).[1] Transdermal estradiol has less-pronounced effects on these proteins and, in contrast to oral estradiol, reduces triglycerides.[1] Through these effects, both oral and transdermal estrogens can protect against atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease in menopausal women with intact arterial endothelium that is without severe lesions.[1]

Approximately 95% of orally ingested estradiol is inactivated during first-pass metabolism.[77] Nonetheless, levels of estradiol in the liver with oral administration are supraphysiological and approximately 4- to 5-fold higher than in circulation due to the first-pass.[1][97] This does not occur with parenteral routes of estradiol, such as transdermal, vaginal, or injection.[1] In contrast to estradiol, ethinylestradiol is much more resistant to hepatic metabolism, with a mean oral bioavailability of approximately 45%,[98] and the transdermal route has a similar impact on hepatic protein synthesis as the oral route.[99] Conjugated estrogens are also more resistant to hepatic metabolism than estradiol and show disproportionate effects on hepatic protein production as well, although not to the same magnitude as ethinylestradiol.[1] These differences are considered to be responsible for the greater risk of cardiovascular events with ethinylestradiol and conjugated estrogens relative to estradiol.[1]

High-dosage oral synthetic estrogens like diethylstilbestrol and ethinylestradiol are associated with fairly high rates of severe cardiovascular complications.[100][101] Diethylstilbestrol has been associated with an up to 35% risk of cardiovascular toxicity and death and a 15% incidence of VTE in men treated with it for prostate cancer.[100][101] In contrast to oral synthetic estrogens, high-dosage polyestradiol phosphate and transdermal estradiol have not been found to increase the risk of cardiovascular mortality or thromboembolism in men with prostate cancer, although significantly increased cardiovascular morbidity (due mainly to an increase in non-fatal ischemic heart events and heart decompensation) has been observed with polyestradiol phosphate.[101][102][103]

Sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) levels indicate hepatic estrogenic exposure and may be a surrogate marker for coagulation and VTE risk with estrogen therapy, although this topic has been debated.[104][105][106] SHBG levels with birth control pills containing different progestins are increased by 1.5 to 2-fold with levonorgestrel, 2.5- to 4-fold with desogestrel and gestodene, 3.5- to 4-fold with drospirenone and dienogest, and 4- to 5-fold with cyproterone acetate.[104] Contraceptive vaginal rings and contraceptive patches likewise have been found to increase SHBG levels by 2.5-fold and 3.5-fold, respectively.[104] Birth control pills containing high doses of ethinylestradiol (>50 μg) can increase SHBG levels by 5- to 10-fold, which is similar to the increase that occurs during pregnancy.[107] Conversely, increases in SHBG levels are much lower with estradiol, especially when used parenterally.[108][109][110][111][112] High-dose parenteral polyestradiol phosphate therapy has been found to increase SHBG levels by about 1.5-fold.[111]

| v]] · [[Template talk:Risk of venous thromboembolism with hormone therapy and birth control pills (QResearch/CPRD) | d]] · e

Risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) with hormone therapy and birth control (QResearch/CPRD) | ||

| Type | Route | Medications | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menopausal hormone therapy | Oral | Estradiol alone ≤1 mg/day >1 mg/day |

1.27 (1.16–1.39)* 1.22 (1.09–1.37)* 1.35 (1.18–1.55)* |

| Conjugated estrogens alone ≤0.625 mg/day >0.625 mg/day |

1.49 (1.39–1.60)* 1.40 (1.28–1.53)* 1.71 (1.51–1.93)* | ||

| Estradiol/medroxyprogesterone acetate | 1.44 (1.09–1.89)* | ||

| Estradiol/dydrogesterone ≤1 mg/day E2 >1 mg/day E2 |

1.18 (0.98–1.42) 1.12 (0.90–1.40) 1.34 (0.94–1.90) | ||

| Estradiol/norethisterone ≤1 mg/day E2 >1 mg/day E2 |

1.68 (1.57–1.80)* 1.38 (1.23–1.56)* 1.84 (1.69–2.00)* | ||

| Estradiol/norgestrel or estradiol/drospirenone | 1.42 (1.00–2.03) | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/medroxyprogesterone acetate | 2.10 (1.92–2.31)* | ||

| Conjugated estrogens/norgestrel ≤0.625 mg/day CEEs >0.625 mg/day CEEs |

1.73 (1.57–1.91)* 1.53 (1.36–1.72)* 2.38 (1.99–2.85)* | ||

| Tibolone alone | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) | ||

| Raloxifene alone | 1.49 (1.24–1.79)* | ||

| Transdermal | Estradiol alone ≤50 μg/day >50 μg/day |

0.96 (0.88–1.04) 0.94 (0.85–1.03) 1.05 (0.88–1.24) | |

| Conjugated estrogens alone | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | ||

| Estradiol/progestogen | 0.88 (0.73–1.01) | ||

| Vaginal | Estradiol alone | 0.84 (0.73–0.97) | |

| Combined birth control | Oral | Ethinylestradiol/norethisterone | 2.56 (2.15–3.06)* |

| Ethinylestradiol/levonorgestrel | 2.38 (2.18–2.59)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/norgestimate | 2.53 (2.17–2.96)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/desogestrel | 4.28 (3.66–5.01)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/gestodene | 3.64 (3.00–4.43)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/drospirenone | 4.12 (3.43–4.96)* | ||

| Ethinylestradiol/cyproterone acetate | 4.27 (3.57–5.11)* | ||

| Notes: (1) Nested case–control studies (2015, 2019) based on data from the QResearch and Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) databases. (2) Bioidentical progesterone was not included, but is known to be associated with no additional risk. Footnotes: * = Statistically significant (p < 0.01). Sources: See template. | |||

Breast cancer

Estrogens are responsible for breast development and, in relation to this, are strongly implicated in the development of breast cancer.[113][114] In addition, estrogens stimulate the growth and accelerate the progression of ER-positive breast cancer.[115][116] In accordance, antiestrogens like the selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) tamoxifen, the ER antagonist fulvestrant, and the aromatase inhibitors (AIs) anastrozole and exemestane are all effective in the treatment of ER-positive breast cancer.[117][118][119] Antiestrogens are also effective in the prevention of breast cancer.[120][121][122] Paradoxically, high-dose estrogen therapy is effective in the treatment of breast cancer as well and has about the same degree of effectiveness as antiestrogen therapy, although it is far less commonly used due to adverse effects.[123][124] The usefulness of high-dose estrogen therapy in the treatment of ER-positive breast cancer is attributed to a bimodal effect in which high concentrations of estrogens signal breast cancer cells to undergo apoptosis, in contrast to lower concentrations of estrogens which stimulate their growth.[123][124]

A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 studies assessed the risk of breast cancer in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women treated with estrogens for menopausal symptoms.[125] They found that treatment with estradiol only is not associated with an increased risk of breast cancer (OR = 0.90 in RCTs and OR = 1.11 in observational studies).[125] This was in accordance with a previous analysis of estrogen-only treatment with estradiol or conjugated estrogens which similarly found no increased risk (RR = 0.99).[125] Moreover, another study found that the risk of breast cancer with estradiol and conjugated estrogens was not significantly different (RR = 1.15 for conjugated estrogens versus estradiol).[125] These findings are paradoxical because oophorectomy in premenopausal women and antiestrogen therapy in postmenopausal women are well-established as considerably reducing the risk of breast cancer (RR = 0.208 to 0.708 for chemoprevention with antiestrogens in postmenopausal women).[120][121][122] However, there are indications that there may be a ceiling effect such that past a certain low concentration threshold (e.g., approximately 10.2 pg/mL for estradiol), additional estrogens alone may not further increase the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women.[126] There are also indications that the fluctuations in estrogen levels across the normal menstrual cycle in premenopausal women may be important for breast cancer risk.[127]

In contrast to estrogen-only therapy, combined estrogen and progestogen treatment, although dependent on the progestogen used, is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.[125][128] The increase in risk is dependent on the duration of treatment, with more than five years (OR = 2.43) having a significantly greater risk than less than five years (OR = 1.49).[125] In addition, sequential estrogen–progestogen treatment (OR = 1.76) is associated with a lower risk increase than continuous treatment (OR = 2.90), which has a comparably much higher risk.[125] The increase in risk also differs according to the specific progestogen used.[125] Treatment with estradiol plus medroxyprogesterone acetate (OR = 1.19), norethisterone acetate (OR = 1.44), levonorgestrel (OR = 1.47), or a mixed progestogen subgroup (OR = 1.99) were all associated with an increased risk.[125] In a previous review, the increase in breast cancer risk was found to not be significantly different between these three progestogens.[125] Conversely, there is no significant increase in risk of breast cancer with bioidentical progesterone (OR = 1.00) or with the atypical progestin dydrogesterone (OR = 1.10).[125] In accordance, another study found similarly that the risk of breast cancer was not significantly increased with estrogen–progesterone (RR = 1.00) or estrogen–dydrogesterone (RR = 1.16) but was increased for estrogen combined with other progestins (RR = 1.69).[75] These progestins included chlormadinone acetate, cyproterone acetate, medrogestone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, nomegestrol acetate, norethisterone acetate, and promegestone, with the associations for breast cancer risk not differing significantly between the different progestins in this group.[75]

In contrast to cisgender women, breast cancer is extremely rare in men and transgender women treated with estrogens and/or progestogens, and gynecomastia or breast development in such individuals does not appear to be associated with an increased risk of breast cancer.[129][130][131][132] Likewise, breast cancer has never been reported in women with complete androgen insensitivity syndrome, who similarly have a male genotype (46,XY), in spite of the fact that these women have well-developed breasts.[133][134] The reasons for these differences are unknown. However, the dramatically increased risk of breast cancer (20- to 58-fold) in men with Klinefelter's syndrome, who have somewhat of a hybrid of a male and a female genotype (47,XXY), suggests that it may have to do with the sex chromosomes.[132][135][136]

Cholestatic hepatotoxicity

Estrogens, along with progesterone, can rarely cause cholestatic hepatotoxicity, particularly at very high concentrations.[137][138][139] This is seen in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, which occurs in 0.4 to 15% of pregnancies (highly variable depending on the country).[140][141][142][143]

Gallbladder disease

Estrogen therapy has been associated with gallbladder disease, including risk of gallstone formation.[144][145][146][147] A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis found that menopausal hormone therapy significantly increased the risk of gallstones (RR = 1.79) while oral contraceptives did not significantly increase the risk (RR = 1.19).[147] Biliary sludge appears in 5 to 30% of women during pregnancy, and definitive gallstones persisting postpartum become established in approximately 5%.[148]

Overdose

Estrogens are relatively safe in overdose and symptoms manifest mainly as reversible feminization.

Interactions

Inducers of cytochrome P450 enzymes like carbamazepine and phenytoin can accelerate the metabolism of estrogens and thereby decrease their bioavailability and circulating levels. Inhibitors of such enzymes can have the opposite effect and can increase estrogen levels and bioavailability.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Estrogens act as selective agonists of the estrogen receptors (ERs), the ERα and the ERβ. They may also bind to and activate membrane estrogen receptors (mERs) such as the GPER. Estrogens do not have off-target activity at other steroid hormone receptors such as the androgen, progesterone, glucocorticoid, or mineralocorticoid receptors, nor do they have neurosteroid activity by interacting with neurotransmitter receptors, unlike various progestogens and some other steroids. Given by subcutaneous injection in mice, estradiol is about 10-fold more potent than estrone and about 100-fold more potent than estriol.[149]

Estrogens have antigonadotropic effects at sufficiently high concentrations via activation of the ER and hence can suppress the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. This is caused by negative feedback, resulting in a suppression in secretion and decreased circulating levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). The antigonadotropic effects of estrogens interfere with fertility and gonadal sex hormone production. They are responsible for the hormonal contraceptive effects of estrogens. In addition, they allow estrogens to act as functional antiandrogens by suppressing gonadal testosterone production. At sufficiently high doses, estrogens are able to suppress testosterone levels into the castrate range in men.[150]

Estrogens differ significantly in their pharmacological properties.[1][151][152] For instance, due to structural differences and accompanying differences in metabolism, estrogens differ from one another in their tissue selectivity; synthetic estrogens like ethinylestradiol and diethylstilbestrol are not inactivated as efficiently as estradiol in tissues like the liver and uterus and as a result have disproportionate effects in these tissues.[1] This can result in issues such as a relatively higher risk of thromboembolism.[1]

In-vitro pharmacodynamics

In-vivo pharmacodynamics

| Estrogen | Form | Major brand names | EPD | CIC-D | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estradiol | Oil solution | – | 40–60 mg | – | 1–2 mg ≈ 1–2 days | |

| Aqueous suspension | Aquadiol, Diogyn, Progynon, Mego-E | ? | 3.5 mg | 0.5–2 mg ≈ 2–7 days; 3.5 mg ≈ >5 days | ||

| Microspheres | Juvenum-E, Juvenum | ? | – | 1 mg ≈ 30 days | ||

| Estradiol benzoate | Oil solution | Progynon-B | 25–35 mg | – | 1.66 mg ≈ 2–3 days; 5 mg ≈ 3–6 days | |

| Aqueous suspension | Agofollin-Depot, Ovocyclin M | 20 mg | – | 10 mg ≈ 16–21 days | ||

| Emulsion | Menformon-Emulsion, Di-Pro-Emulsion | ? | – | 10 mg ≈ 14–21 days | ||

| Estradiol dipropionate | Oil solution | Agofollin, Di-Ovocylin, Progynon DP | 25–30 mg | – | 5 mg ≈ 5–8 days | |

| Estradiol valerate | Oil solution | Delestrogen, Progynon Depot, Mesigyna | 20–30 mg | 5 mg | 5 mg ≈ 7–8 days; 10 mg ≈ 10–14 days; 40 mg ≈ 14–21 days; 100 mg ≈ 21–28 days | |

| Estradiol benzoate butyrate | Oil solution | Redimen, Soluna, Unijab | ? | 10 mg | 10 mg ≈ 21 days | |

| Estradiol cypionate | Oil solution | Depo-Estradiol, Depofemin | 20–30 mg | – | 5 mg ≈ 11–14 days | |

| Aqueous suspension | Cyclofem, Lunelle | ? | 5 mg | 5 mg ≈ 14–24 days | ||

| Estradiol enanthate | Oil solution | Perlutal, Topasel, Yectames | ? | 5–10 mg | 10 mg ≈ 20–30 days | |

| Estradiol dienanthate | Oil solution | Climacteron, Lactimex, Lactostat | ? | – | 7.5 mg ≈ >40 days | |

| Estradiol undecylate | Oil solution | Delestrec, Progynon Depot 100 | ? | – | 10–20 mg ≈ 40–60 days; 25–50 mg ≈ 60–120 days | |

| Polyestradiol phosphate | Aqueous solution | Estradurin | 40–60 mg | – | 40 mg ≈ 30 days; 80 mg ≈ 60 days; 160 mg ≈ 120 days | |

| Estrone | Oil solution | Estrone, Kestrin, Theelin | ? | – | 1–2 mg ≈ 2–3 days | |

| Aqueous suspension | Estrone Aq. Susp., Kestrone, Theelin Aq. | ? | – | 0.1–2 mg ≈ 2–7 days | ||

| Estriol | Oil solution | – | ? | – | 1–2 mg ≈ 1–4 days | |

| Polyestriol phosphate | Aqueous solution | Gynäsan, Klimadurin, Triodurin | ? | – | 50 mg ≈ 30 days; 80 mg ≈ 60 days | |

| Notes: All aqueous suspensions are of microcrystalline particle size. Estradiol production during the menstrual cycle is 30–640 µg/day (6.4–8.6 mg total per month or cycle). The vaginal epithelium maturation dosage of estradiol benzoate or estradiol valerate has been reported as 5 to 7 mg/week. An effective ovulation-inhibiting dose of estradiol undecylate is 20–30 mg/month. Sources: See template. | ||||||

Pharmacokinetics

Estrogens can be administered via a variety of routes, including by mouth, sublingual, transdermal/topical (gel, patch), vaginal (gel, tablet, ring), rectal, intramuscular, subcutaneous, intravenous, and subcutaneous implant. Natural estrogens generally have low oral bioavailability while synthetic estrogens have higher bioavailability. Parenteral routes have higher bioavailability. Estrogens are typically bound to albumin and/or sex hormone-binding globulin in the circulation. They are metabolized in the liver by hydroxylation (via cytochrome P450 enzymes), dehydrogenation (via 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase), and conjugation (via sulfation and glucuronidation). The elimination half-lives of estrogens vary by estrogen and route of administration. Estrogens are eliminated mainly by the kidneys via the urine as conjugates.

| Compound | RBA to SHBG (%) |

Bound to SHBG (%) |

Bound to albumin (%) |

Total bound (%) |

MCR (L/day/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17β-Estradiol | 50 | 37 | 61 | 98 | 580 |

| Estrone | 12 | 16 | 80 | 96 | 1050 |

| Estriol | 0.3 | 1 | 91 | 92 | 1110 |

| Estrone sulfate | 0 | 0 | 99 | 99 | 80 |

| 17β-Dihydroequilin | 30 | ? | ? | ? | 1250 |

| Equilin | 8 | 26 | 13 | ? | 2640 |

| 17β-Dihydroequilin sulfate | 0 | ? | ? | ? | 375 |

| Equilin sulfate | 0 | ? | ? | ? | 175 |

| Δ8-Estrone | ? | ? | ? | ? | 1710 |

| Notes: RBA for SHBG (%) is compared to 100% for testosterone. Sources: See template. | |||||

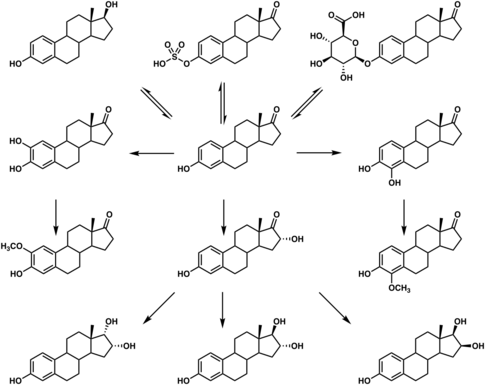

Chemistry

Estrogens can be grouped as steroidal or nonsteroidal. The steroidal estrogens are estranes and include estradiol and its analogues, such as ethinylestradiol and conjugated estrogens like equilin sulfate. Nonsteroidal estrogens belong predominantly to the stilbestrol group of compounds and include diethylstilbestrol and hexestrol, among others.

Estrogen esters are esters and prodrugs of the corresponding parent estrogens. Examples include estradiol valerate and diethylstilbestrol dipropionate, which are prodrugs of estradiol and diethylstilbestrol, respectively. Estrogen esters with fatty acid esters have increased lipophilicity and a prolonged duration of action when administered by intramuscular or subcutaneous injection. Some estrogen esters, such as polyestradiol phosphate, polyestriol phosphate, and polydiethylstilbestrol phosphate, are in the form of polymers.

History

| Generic name | Class | Brand name | Route | Intr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorotrianisene | NS | Tace[lower-alpha 1] | PO | 1952 |

| Conjugated estriol | S/ester | Emmenin[lower-alpha 1] | PO | 1930 |

| Diethylstilbestrol dipropionate | NS/ester | Synestrin[lower-alpha 1] | IM | 1940s |

| Estradiol dipropionate | S/ester | Agofollin[lower-alpha 1] | IM | 1939 |

| Estrogenic substances | S | Amniotin[lower-alpha 1] | PO, IM, TD, V | 1929 |

| Estrone | S | Theelin[lower-alpha 1] | IM | 1929 |

| Ethinylestradiol sulfonate | S/alkyl/ester | Deposiston[lower-alpha 1] | PO | 1978 |

| Methallenestril | NS/ether | Vallestril | PO | 1950s |

| Moxestrol | S/alkyl | Surestryl | PO | 1970s |

| Polyestriol phosphate | S/ester | Triodurin[lower-alpha 1] | IM | 1968 |

| Quinestrol | S/alkyl/ether | Estrovis | PO | 1960s |

Ovarian extracts were available in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but were inert or had extremely low estrogenic activity and were regarded as ineffective.[156][157][158] In 1927, Selmar and Aschheim discovered that large amounts of estrogens were present in the urine of pregnant women.[157][159][160] This rich source of estrogens, produced by the placenta, allowed for the development of potent estrogenic formulations for scientific and clinical use.[157][160][161] The first pharmaceutical estrogen product was a conjugated estriol called Progynon, a placental extract, and was introduced for medical use by the Germany pharmaceutical company Schering in 1928.[162][163][164][165][166][167][168][169] In 1929, Adolf Butenandt and Edward Adelbert Doisy independently isolated and purified estrone, the first estrogen to be discovered.[170] The estrogen preparations Amniotin (Squibb), Progynon (Schering), and Theelin (Parke-Davis) were all on the market by 1929,[156] and various additional preparations such as Emmenin, Folliculin, Menformon, Oestroform, and Progynon B, containing purified estrogens or mixtures of estrogens, were on the market by 1934.[157][171][172] Estrogens were originally known under a variety of different names including estrogens, estrins, follicular hormones, folliculins, gynecogens, folliculoids, and female sex hormones, among others.[173][171]

An estrogen patch was reportedly marketed by Searle in 1928,[174][175] and an estrogen nasal spray was studied by 1929.[176]

In 1938, British scientists obtained a patent on a newly formulated nonsteroidal estrogen, diethylstilbestrol (DES), that was cheaper and more powerful than the previously manufactured estrogens. Soon after, concerns over the side effects of DES were raised in scientific journals while the drug manufacturers came together to lobby for governmental approval of DES. It was only until 1941 when estrogen therapy was finally approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of menopausal symptoms.[177] Conjugated estrogens (brand name Premarin) was introduced in 1941 and succeeded Emmenin, the sales of which had begun to drop after 1940 due to competition from DES.[178] Ethinylestradiol was synthesized in 1938 by Hans Herloff Inhoffen and Walter Hohlweg at Schering AG in Berlin[179][180][181][182][183] and was approved by the FDA in the U.S. on 25 June 1943 and marketed by Schering as Estinyl.[184]

Micronized estradiol, via the oral route, was first evaluated in 1972,[185] and this was followed by the evaluation of vaginal and intranasal micronized estradiol in 1977.[186] Oral micronized estradiol was first approved in the United States under the brand name Estrace in 1975.[187]

Society and culture

Availability

Estrogens are widely available throughout the world.[4]

Research

Male birth control

High-dose estrogen therapy is effective in suppressing spermatogenesis and fertility in men, and hence as a male contraceptive.[188][189] It works both by strongly suppressing gonadotropin secretion and gonadal testosterone production and via direct effects on the testes.[189][190] After a sufficient course of therapy, only Sertoli cells and spermatogonia remain in the seminiferous tubules of the testes, with a variety of other testicular abnormalities observable.[188][189] The use of estrogens for contraception in men is precluded by major side effects such as sexual dysfunction, feminization, gynecomastia, and metabolic changes.[188] In addition, there is evidence that with long-term therapy, fertility and gonadal sex hormone production in men may not return following discontinuation of high-dose estrogen therapy.[190]

Eating disorders

Estrogen has been used as a treatment for women with bulimia nervosa, in addition to cognitive behavioral therapy, which is the established standard for treatment in bulimia cases. The estrogen research hypothesizes that the disease may be linked to a hormonal imbalance in the brain.[191]

Miscellaneous

Estrogens have been used in studies which indicate that they may be effective in the treatment of traumatic liver injury.[192]

In humans and mice, estrogens promote wound healing.[193]

Estrogen therapy has been proposed as a potential treatment for autism but clinical studies are needed.[194]

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration". Climacteric 8 (Suppl 1): 3–63. 2005. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947. http://hormonebalance.org/images/documents/Kuhl%2005%20%20Pharm%20Estro%20Progest%20Climacteric_1313155660.pdf.

- ↑ Kuhl H (2011). "Pharmacology of Progestogens". J Reproduktionsmed Endokrinol 8 (1): 157–177. http://www.kup.at/kup/pdf/10168.pdf.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "IBM Watson Health Products: Please Login". http://www.micromedexsolutions.com.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sweetman, Sean C., ed (2009). "Sex Hormones and their Modulators". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (36th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85369-840-1. https://www.medicinescomplete.com/mc/martindale/2009/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "List of Estrogens". https://www.drugs.com/drug-class/estrogens.html.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=5GpcTQD_L2oC.

- ↑ J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=0vXTBwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ "Initial 17beta-estradiol dose for treating vasomotor symptoms". Obstet Gynecol 95 (5): 726–31. May 2000. doi:10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00643-2. PMID 10775738.

- ↑ Wiegratz, I.; Kuhl, H. (2007). "Praxis der Hormontherapie in der Peri- und Postmenopause". Gynäkologische Endokrinologie 5 (3): 141–149. doi:10.1007/s10304-007-0194-9. ISSN 1610-2894.

- ↑ "NIH – Menopausal Hormone Therapy Information". National Institutes of Health. 27 August 2007. http://www.nih.gov/PHTindex.htm.

- ↑ "Effects of transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on cardiovascular risk factors". Treat Endocrinol 5 (1): 37–51. 2006. doi:10.2165/00024677-200605010-00005. PMID 16396517.

- ↑ Alfred S. Wolf; H.P.G. Schneider (12 March 2013). Östrogene in Diagnostik und Therapie. Springer-Verlag. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-3-642-75101-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=IArLBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA77.

- ↑ "Hormonal and Surgical Treatment Options for Transgender Women and Transfeminine Spectrum Persons". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 40 (1): 99–111. March 2017. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.006. PMID 28159148.

- ↑ "Hormone therapy for transgender patients". Transl Androl Urol 5 (6): 877–884. December 2016. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04. PMID 28078219.

- ↑ "Oestrogen and anti-androgen therapy for transgender women". Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 5 (4): 291–300. April 2017. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(16)30319-9. PMID 27916515.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "The evolving role of estrogen therapy in prostate cancer". Clin Genitourinary Cancer 1 (2): 81–9. 2002. doi:10.3816/CGC.2002.n.009. PMID 15046698.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 William R. Miller; James N. Ingle (8 March 2002). Endocrine Therapy in Breast Cancer. CRC Press. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-0-203-90983-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=00_LBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA49.

- ↑ Maximov, Philipp Y.; McDaniel, Russell E.; Jordan, V. Craig (2013). "Discovery and Pharmacology of Nonsteroidal Estrogens and Antiestrogens". Tamoxifen. Milestones in Drug Therapy. pp. 1–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-0664-0_1. ISBN 978-3-0348-0663-3.

- ↑ J. Aiman (6 December 2012). Infertility: Diagnosis and Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-1-4613-8265-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=D4_TBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA133.

- ↑ Glenn L. Schattman; Sandro Esteves; Ashok Agarwal (12 May 2015). Unexplained Infertility: Pathophysiology, Evaluation and Treatment. Springer. pp. 266–. ISBN 978-1-4939-2140-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=wCdACQAAQBAJ&pg=PA266.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Oestrogen supplementation, mainly diethylstilbestrol, for preventing miscarriages and other adverse pregnancy outcomes". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010 (3): CD004353. 2003. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004353. PMID 12918007.

- ↑ J.B. Josimovich (11 November 2013). Gynecologic Endocrinology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 482–. ISBN 978-1-4613-2157-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=9vv2BwAAQBAJ&pg=PA482.

- ↑ Marshall S. Shapo (30 December 2008). Experimenting with the Consumer: The Mass Testing of Risky Products on the American Public: The Mass Testing of Risky Products on the American Public. ABC-CLIO. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-0-313-36529-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=VoVfwfe339oC&pg=PA137.

- ↑ "Tall girls: the social shaping of a medical therapy". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160 (10): 1077–8. 2006. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.10.1035. PMID 17018462.

- ↑ "Attenuating growth in children with profound developmental disability: a new approach to an old dilemma". Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 160 (10): 1013–7. 2006. doi:10.1001/archpedi.160.10.1013. PMID 17018459.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "Estrogens and selective estrogen receptor modulators in acromegaly". Endocrine 54 (2): 306–314. November 2016. doi:10.1007/s12020-016-1118-z. PMID 27704479.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Estrogen and selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for the treatment of acromegaly: a meta-analysis of published observational studies". Pituitary 17 (3): 284–95. June 2014. doi:10.1007/s11102-013-0504-2. PMID 23925896.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Estrogen treatment for acromegaly". Pituitary 15 (4): 601–7. December 2012. doi:10.1007/s11102-012-0426-4. PMID 22933045.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 "The World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the biological treatment of paraphilias". World J. Biol. Psychiatry 11 (4): 604–55. 2010. doi:10.3109/15622971003671628. PMID 20459370.

- ↑ Bradford, J. M. W. (1990). "The Antiandrogen and Hormonal Treatment of Sex Offenders". Handbook of Sexual Assault. Springer US. pp. 297–310. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-0915-2_17. ISBN 978-1-4899-0917-6.

- ↑ "Flutamide. A preliminary review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties, and therapeutic efficacy in advanced prostatic cancer". Drugs 38 (2): 185–203. August 1989. doi:10.2165/00003495-198938020-00003. PMID 2670515. "A favourable feature of flutamide therapy has been its lesser effect on libido and sexual potency; fewer than 20% of patients treated with flutamide alone reported such changes. In contrast, nearly all patients treated with oestrogens or estramustine phosphate reported loss of sexual potency. [...] In comparative therapeutic trials, loss of potency has occurred in all patients treated with stilboestrol or estramustine phosphate compared with 0 to 20% of those given flutamide alone (Johansson et al. 1987; Lund & Rasmussen 1988).".

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Gunther Göretzlehner; Christian Lauritzen; Thomas Römer; Winfried Rossmanith (1 January 2012). Praktische Hormontherapie in der Gynäkologie. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 385–. ISBN 978-3-11-024568-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=TIs2WhfYzZ4C&pg=PA385.

- ↑ R.E. Mansel; Oystein Fodstad; Wen G. Jiang (14 June 2007). Metastasis of Breast Cancer. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 217–. ISBN 978-1-4020-5866-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=14pb5b6gT-oC&pg=PA217.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 "Hormonal breast augmentation: prognostic relevance of insulin-like growth factor-I". Gynecol. Endocrinol. 12 (2): 123–7. 1998. doi:10.3109/09513599809024960. PMID 9610425.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Lauritzen, C (1980). "Hormonkur kann hypoplastischer Mamma aufhelfen" (in de). Selecta (Planegg: Selecta-Verlag) 22 (43): 3798–3801. ISSN 0582-4877. OCLC 643821347.

- ↑ Kaiser, Rolf; Leidenberger, Freimut A. (1991). Hormonbehandlung in der gynäkologischen Praxis (6 ed.). Stuttgart, New York: Georg Thieme Verlag. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-3133574075.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 37.5 37.6 37.7 37.8 "Guidelines for the Evaluation and Treatment of Perimenopausal Depression: Summary and Recommendations". J Womens Health (Larchmt) 28 (2): 117–134. February 2019. doi:10.1089/jwh.2018.27099.mensocrec. PMID 30182804.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 38.7 "Management of depressive symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women: EMAS position statement". Maturitas 131: 91–101. January 2020. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.11.002. PMID 31740049.

- ↑ "Depression during perimenopause: the role of the obstetrician-gynecologist". Arch Womens Ment Health 23 (1): 1–10. 2020. doi:10.1007/s00737-019-0950-6. PMID 30758732.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Cognition, Mood and Sleep in Menopausal Transition: The Role of Menopause Hormone Therapy". Medicina 55 (10): 668. October 2019. doi:10.3390/medicina55100668. PMID 31581598.

- ↑ "Hormone therapy and mood in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women: a narrative review". Menopause 22 (5): 564–78. May 2015. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000323. PMID 25203891.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 "Pharmacotherapeutic approaches to treating depression during the perimenopause". Expert Opin Pharmacother 20 (15): 1837–1845. October 2019. doi:10.1080/14656566.2019.1645122. PMID 31355688.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Efficacy of estradiol in perimenopausal depression: so much promise and so few answers". Depress Anxiety 32 (8): 539–49. August 2015. doi:10.1002/da.22391. PMID 26130315.

- ↑ "A meta-analysis of the effect of hormone replacement therapy upon depressed mood". Psychoneuroendocrinology 22 (3): 189–212. April 1997. doi:10.1016/s0306-4530(96)00034-0. PMID 9203229.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "Is there a role for reproductive steroids in the etiology and treatment of affective disorders?". Dialogues Clin Neurosci 20 (3): 187–196. September 2018. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2018.20.3/drubinow. PMID 30581288.

- ↑ Myoraku, Alison; Robakis, Thalia; Rasgon, Natalie (2018). "Estrogen-Based Hormone Therapy for Depression Related to Reproductive Events". Current Treatment Options in Psychiatry 5 (4): 416–424. doi:10.1007/s40501-018-0156-y. ISSN 2196-3061.

- ↑ Cheng, Yu-Shian; Tseng, Ping-Tao; Tu, Yu-Kang; Wu, Yi-Cheng; Su, Kuan-Pin; Wu, Ching-Kuan; Li, Dian-Jeng; Chen, Tien-Yu et al. (19 September 2019), Hormonal and Pharmacologic Interventions for Depressive Symptoms in Peri- And/Or Post-Menopausal Women: A Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials, doi:10.2139/ssrn.3457416

- ↑ "Estrogen augmentation in schizophrenia: a quantitative review of current evidence". Schizophr. Res. 141 (2–3): 179–84. November 2012. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2012.08.016. PMID 22998932.

- ↑ "Treating schizophrenia during menopause". Menopause 24 (5): 582–588. May 2017. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000772. PMID 27824682.

- ↑ "Estrogens and the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia: Possible neuroprotective mechanisms". Front Neuroendocrinol 47: 19–33. October 2017. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2017.06.003. PMID 28673758.

- ↑ "Considering the role of adolescent sex steroids in schizophrenia". J. Neuroendocrinol. 30 (2): e12538. February 2018. doi:10.1111/jne.12538. PMID 28941299.

- ↑ "Homeostasis of the sebaceous gland and mechanisms of acne pathogenesis". Br. J. Dermatol. 181 (4): 677–690. October 2019. doi:10.1111/bjd.17981. PMID 31056753.

- ↑ "Treatment of acne vulgaris". J Am Med Assoc 146 (12): 1107–13. July 1951. doi:10.1001/jama.1951.03670120017005. PMID 14841085.

- ↑ "Diethylstilbestrol therapy in young men with acne; correlation with the urinary 17-ketosteroids". AMA Arch Derm Syphilol 65 (5): 601–8. May 1952. doi:10.1001/archderm.1952.01530240093012. PMID 14914180.

- ↑ "Use of synthetic estrogenic substance chlorotrianisene (TACE) in treatment of acne". AMA Arch Derm Syphilol 69 (4): 418–27. April 1954. doi:10.1001/archderm.1954.01540160020004. PMID 13147544.

- ↑ "The acne problem". AMA Arch Derm Syphilol 67 (2): 173–83. February 1953. doi:10.1001/archderm.1953.01540020051010. PMID 13029903.

- ↑ "The management of acne vulgaris". Postgrad Med 12 (1): 34–40. July 1952. doi:10.1080/00325481.1952.11708046. PMID 14957675.

- ↑ "Acne, estrogens and spermatozoa". Arch Dermatol 81: 53–8. January 1960. doi:10.1001/archderm.1960.03730010057006. PMID 14425194.

- ↑ "Sebaceous gland suppression with ethinyl estradiol and diethylstilbestrol". Arch Dermatol 108 (2): 210–4. August 1973. doi:10.1001/archderm.1973.01620230010003. PMID 4269283.

- ↑ "Non-steroidal steroid receptor modulators". IDrugs 9 (7): 488–94. July 2006. doi:10.2174/0929867053764671. PMID 16821162.

- ↑ "Drospirenone/Estetrol - Mithra Pharmaceuticals - AdisInsight". http://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800034634.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Llewellyn, William (2011). Anabolics. Molecular Nutrition Llc. pp. 9–10,294–297,385–394,402–412,444–454,460–467,483–490,575–583. ISBN 978-0-9828280-1-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=afKLA-6wW0oC&pg=PT10.

- ↑ "Inherent estrogenicity of norethindrone and norethynodrel: comparison with other synthetic progestins and progesterone". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 22 (10): 1033–9. 1962. doi:10.1210/jcem-22-10-1033. PMID 13942007.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "Clinical use of oestrogens and progestogens". Maturitas 12 (3): 199–214. September 1990. doi:10.1016/0378-5122(90)90004-P. PMID 2215269.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Christian Lauritzen; John W. W. Studd (22 June 2005). Current Management of the Menopause. CRC Press. pp. 95–98,488. ISBN 978-0-203-48612-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=WD7S7677xUUC&pg=PA95.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Laurtizen, Christian (2001). "Hormone Substitution Before, During and After Menopause". in Fisch, Franz H.. Menopause – Andropause: Hormone Replacement Therapy Through the Ages. Krause & Pachernegg: Gablitz. pp. 67–88. ISBN 978-3-901299-34-6. https://www.kup.at/kup/pdf/4978.pdf.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Midwinter, Audrey (1976). "Contraindications to estrogen therapy and management of the menopausal syndrome in these cases". in Campbell, Stuart. The Management of the Menopause & Post-Menopausal Years: The Proceedings of the International Symposium held in London 24–26 November 1975 Arranged by the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, The University of London. MTP Press Limited. pp. 377–382. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-6165-7_33. ISBN 978-94-011-6167-1.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 68.2 68.3 "Ethinyl oestradiol". Br Med J 2 (4583): 809–12. November 1948. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4583.809. PMID 18890306.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Lebech, P. E. (1976). "Effects and Side-effects of Estrogen Therapy". Consensus on Menopause Research. Springer Netherlands. pp. 44–47. doi:10.1007/978-94-011-7179-3_10. ISBN 978-94-011-7181-6.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 "Estrogen replacement therapy". Clin Obstet Gynecol 29 (2): 407–30. June 1986. doi:10.1097/00003081-198606000-00022. PMID 3522011.

- ↑ "Are all estrogens the same?". Maturitas 47 (4): 269–75. April 2004. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2003.11.009. PMID 15063479.

- ↑ "A risk-benefit assessment of estrogen therapy in postmenopausal women". Drug Saf 5 (5): 345–58. 1990. doi:10.2165/00002018-199005050-00004. PMID 2222868.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Whitehead, M. (January 1982). "Oestrogens: Relative Potencies and Hepatic Effects After Different Routes of Administration". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 3 (sup1): S11–S16. doi:10.3109/01443618209083065. ISSN 0144-3615.

- ↑ "Pharmaco- and toxicokinetics of selected exogenous and endogenous estrogens: a review of the data and identification of knowledge gaps". Crit Rev Toxicol 44 (8): 696–724. September 2014. doi:10.3109/10408444.2014.930813. PMID 25099693.

- ↑ 75.00 75.01 75.02 75.03 75.04 75.05 75.06 75.07 75.08 75.09 75.10 "Are progestins really necessary as part of a combined HRT regimen?". Climacteric 16 (Suppl 1): 79–84. 2013. doi:10.3109/13697137.2013.803311. PMID 23651281.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "Oral Contraceptives and HRT Risk of Thrombosis". Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost. 24 (2): 217–225. 2018. doi:10.1177/1076029616683802. PMID 28049361.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 "Hormonal contraceptives: pharmacology tailored to women's health". Hum. Reprod. Update 22 (5): 634–46. 2016. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmw016. PMID 27307386.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 "Oral vs Transdermal Estrogen Therapy and Vascular Events: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 100 (11): 4012–20. 2015. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-2237. PMID 26544651.

- ↑ Gregory Y. H. Lip; John E. Hall (28 June 2007). Comprehensive Hypertension E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 865–. ISBN 978-0-323-07067-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=XQajBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA865.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 80.3 80.4 "Hormones and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women". Climacteric 17 (Suppl 2): 34–7. 2014. doi:10.3109/13697137.2014.956717. PMID 25223916.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 81.2 81.3 81.4 81.5 81.6 81.7 81.8 "Menopausal hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism". Prz Menopauzalny 13 (5): 267–72. October 2014. doi:10.5114/pm.2014.46468. PMID 26327865.

- ↑ "Lower risk of cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women taking oral estradiol compared with oral conjugated equine estrogens". JAMA Intern Med 174 (1): 25–31. January 2014. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11074. PMID 24081194.

- ↑ "Esterified estrogens and conjugated equine estrogens and the risk of venous thrombosis". JAMA 292 (13): 1581–7. October 2004. doi:10.1001/jama.292.13.1581. PMID 15467060.

- ↑ "How do you decide on hormone replacement therapy in women with risk of venous thromboembolism?". Blood Rev. 31 (3): 151–157. May 2017. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2016.12.001. PMID 27998619.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 "The risk of venous thrombosis in women over 50 years old using oral contraception or postmenopausal hormone therapy". J. Thromb. Haemost. 11 (1): 124–31. January 2013. doi:10.1111/jth.12060. PMID 23136837.

- ↑ "Hormone replacement therapy with estradiol and risk of venous thromboembolism—a population-based case-control study". Thromb. Haemost. 82 (4): 1218–21. October 1999. doi:10.1055/s-0037-1614363. PMID 10544901.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 "The epidemiology of venous thromboembolism". J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 41 (1): 3–14. 2016. doi:10.1007/s11239-015-1311-6. PMID 26780736.

- ↑ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: Updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone". https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-updated-information-about-risk-blood-clots-women-taking-birth-control.

- ↑ Pramilla Senanayake; Malcolm Potts (14 April 2008). Atlas of Contraception, Second Edition. CRC Press. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-0-203-34732-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=7dDKBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA44.

- ↑ Shlomo Melmed (2016). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 665–. ISBN 978-0-323-29738-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=YZ8_CwAAQBAJ&pg=PA665.

- ↑ "Pregnancy and venous thromboembolism". Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 26 (6): 469–75. 2014. doi:10.1097/GCO.0000000000000115. PMID 25304605. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2FGCO.0000000000000115.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 92.2 92.3 92.4 92.5 "Menopausal hormone therapy: a better and safer future". Climacteric 21 (5): 454–461. March 2018. doi:10.1080/13697137.2018.1439915. PMID 29526116.

- ↑ "Oral estradiol and dydrogesterone combination therapy in postmenopausal women: review of efficacy and safety". Maturitas 76 (1): 10–21. September 2013. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2013.05.018. PMID 23835005. "Dydrogesterone did not increase the risk of VTE associated with oral estrogen (odds ratio (OR) 0.9, 95% CI 0.4–2.3). Other progestogens (OR 3.9, 95% CI 1.5–10.0) were found to further increase the risk of VTE associated with oral estrogen (OR 4.2, 95% CI 1.5–11.6).".

- ↑ "Risk of cardiovascular outcomes in users of estradiol/dydrogesterone or other HRT preparations". Climacteric 12 (5): 445–53. October 2009. doi:10.1080/13697130902780853. PMID 19565370. "The adjusted relative risk of developing a VTE tended to be lower for E/D users (OR 0.84; 95% CI 0.37–1.92) than for users of other HRT (OR 1.42; 95% CI 1.10–1.82), compared to non-users.".

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 95.2 95.3 "Estimates of the risk of cardiovascular death attributable to low-dose oral contraceptives in the United States". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 180 (1 Pt 1): 241–9. January 1999. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70182-1. PMID 9914611.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 96.2 96.3 Kenneth L. Becker (2001). Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1027–. ISBN 978-0-7817-1750-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=FVfzRvaucq8C&pg=PA1027.

- ↑ Marc A. Fritz; Leon Speroff (28 March 2012). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 753–. ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=KZLubBxJEwEC&pg=PA753.

- ↑ "Ethinyl estradiol and 17β-estradiol in combined oral contraceptives: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and risk assessment". Contraception 87 (6): 706–27. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2012.12.011. PMID 23375353.

- ↑ Rogerio A. Lobo (5 June 2007). Treatment of the Postmenopausal Woman: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Academic Press. pp. 177, 770–771. ISBN 978-0-08-055309-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=gywV9hkcyOMC&pg=PA770.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 "Diethylstilboestrol for the treatment of prostate cancer: past, present and future". Scand J Urol 48 (1): 4–14. February 2014. doi:10.3109/21681805.2013.861508. PMID 24256023.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 101.2 "Androgen Deprivation Therapy and the Re-emergence of Parenteral Estrogen in Prostate Cancer". Oncol Hematol Rev 10 (1): 42–47. 2014. doi:10.17925/ohr.2014.10.1.42. PMID 24932461.

- ↑ Waun Ki Hong; James F. Holland (2010). Holland-Frei Cancer Medicine 8. PMPH-USA. pp. 753–. ISBN 978-1-60795-014-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=R0FbhLsWHBEC&pg=PA753.

- ↑ "Estradiol for the mitigation of adverse effects of androgen deprivation therapy". Endocr. Relat. Cancer 24 (8): R297–R313. August 2017. doi:10.1530/ERC-17-0153. PMID 28667081.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 "Can changes in sex hormone binding globulin predict the risk of venous thromboembolism with combined oral contraceptive pills?". Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 81 (6): 482–90. June 2002. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0412.2002.810603.x. PMID 12047300.

- ↑ "Sex hormone-binding globulin as a marker for the thrombotic risk of hormonal contraceptives". J. Thromb. Haemost. 10 (6): 992–7. June 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04720.x. PMID 22469296.

- ↑ "Sex hormone-binding globulin: not a surrogate marker for venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives". Contraception 78 (3): 201–3. September 2008. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.04.004. PMID 18692609.

- ↑ Stephen J. Winters; Ilpo T. Huhtaniemi (25 April 2017). Male Hypogonadism: Basic, Clinical and Therapeutic Principles. Humana Press. pp. 307–. ISBN 978-3-319-53298-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=UFi-DgAAQBAJ&pg=PA307.

- ↑ "Clinical opinion: the biologic and pharmacologic principles of estrogen therapy for symptomatic menopause". MedGenMed 8 (1): 85. March 2006. PMID 16915215.

- ↑ "Are all estrogens created equal? A review of oral vs. transdermal therapy". J Womens Health (Larchmt) 21 (2): 161–9. February 2012. doi:10.1089/jwh.2011.2839. PMID 22011208.

- ↑ "Single drug polyestradiol phosphate therapy in prostatic cancer". Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 11 (Suppl 2): S101–3. 1988. doi:10.1097/00000421-198801102-00024. PMID 3242384.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 "Estrogen therapy and liver function--metabolic effects of oral and parenteral administration". Prostate 14 (4): 389–95. 1989. doi:10.1002/pros.2990140410. PMID 2664738.

- ↑ "Estrogen induction of liver proteins and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol: comparison between estradiol valerate and ethinyl estradiol". Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 22 (4): 198–205. 1986. doi:10.1159/000298914. PMID 3817605.

- ↑ "The role of estrogen in the initiation of breast cancer". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 102 (1–5): 89–96. 2006. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.09.004. PMID 17113977.

- ↑ "Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer". Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 40 (3): 473–84, vii. 2011. doi:10.1016/j.ecl.2011.05.009. PMID 21889715.

- ↑ "Estrogen receptor agonists/antagonists in breast cancer therapy: A critical review". Bioorg. Chem. 71: 257–274. 2017. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.02.011. PMID 28274582.

- ↑ "Estrogen and progesterone receptors in breast cancer". Future Oncol 10 (14): 2293–301. 2014. doi:10.2217/fon.14.110. PMID 25471040.

- ↑ "Endocrine therapy for advanced/metastatic breast cancer". Hematol. Oncol. Clin. North Am. 27 (4): 715–36, viii. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.hoc.2013.05.004. PMID 23915741.

- ↑ "Current medical treatment of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer". World J Biol Chem 6 (3): 231–9. 2015. doi:10.4331/wjbc.v6.i3.231. PMID 26322178.

- ↑ "Fulvestrant for hormone-sensitive metastatic breast cancer". Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1 (1): CD011093. 2017. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011093.pub2. PMID 28043088.