Food physical chemistry

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 8 min

Food physical chemistry is considered to be a branch of Food chemistry[1][2] concerned with the study of both physical and chemical interactions in foods in terms of physical and chemical principles applied to food systems, as well as the applications of physical/chemical techniques and instrumentation for the study of foods.[3][4][5][6] This field encompasses the "physiochemical principles of the reactions and conversions that occur during the manufacture, handling, and storage of foods."[7] Food physical chemistry concepts are often drawn from rheology, theories of transport phenomena, physical and chemical thermodynamics, chemical bonds and interaction forces, quantum mechanics and reaction kinetics, biopolymer science, colloidal interactions, nucleation, glass transitions, and freezing,[8][9] disordered/noncrystalline solids.

Techniques utilized range widely from dynamic rheometry, optical microscopy, electron microscopy, AFM, light scattering, X-ray diffraction/neutron diffraction,[10] to MRI, spectroscopy (NMR,[11] FT-NIR/IR, NIRS, ESR and EPR,[12][13] CD/VCD,[14] Fluorescence, FCS,[15][16][17][18][19] HPLC, GC-MS,[20][21] and other related analytical techniques.

Understanding food processes and the properties of foods requires a knowledge of physical chemistry and how it applies to specific foods and food processes. Food physical chemistry is essential for improving the quality of foods, their stability, and food product development. Because food science is a multi-disciplinary field, food physical chemistry is being developed through interactions with other areas of food chemistry and food science, such as food analytical chemistry, food process engineering/food processing, food and bioprocess technology, food extrusion, food quality control, food packaging, food biotechnology, and food microbiology.

Topics in Food physical chemistry

The following are examples of topics in food physical chemistry that are of interest to both the food industry and food science:

- Water in foods

- Local structure in liquid water

- Micro-crystallization in ice cream emulsions

- Dispersion and surface-adsorption processes in foods

- Water and protein activities

- Food hydration and shelf-life

- Hydrophobic interactions in foods

- Hydrogen bonding and ionic interactions in foods

- Disulfide bond breaking and formation in foods

- Food dispersions

- Structure-functionality in foods

- Food micro- and nano- structure

- Food gels and gelling mechanisms

- Cross-linking in foods

- Starch gelatinization and retrogradation

- Physico-chemical modification of carbohydrates

- Physico-chemical interactions in food formulations

- Freezing effects on foods and freeze concentration of liquids

- Glass transition in wheat gluten and wheat doughs

- Drying of foods and crops

- Rheology of wheat doughs, cheese and meat

- Rheology of extrusion processes

- Food enzyme kinetics

- Immobilized enzymes and cells

- Microencapsulation

- Carbohydrates structure and interactions with water and proteins

- Maillard browning reactions

- Lipids structures and interactions with water and food proteins

- Food proteins structure, hydration and functionality in foods

- Food protein denaturation

- Food enzymes and reaction mechanisms

- Vitamin interactions and preservation during food processing

- Interaction of salts and minerals with food proteins and water

- Color determinations and food grade coloring

- Flavors and sensorial perception of foods

- Properties of food additives

Related fields

- Food chemistry

- Food physics and Rheology

- Biophysical chemistry

- Physical chemistry

- Spectroscopy-applied

- Intermolecular forces

- Nanotechnology and nanostructures

- Chemical physics

- Molecular dynamics

- Surface chemistry and Van der Waals forces

- Chemical reactions and Reaction chemistry

- Quantum chemistry

- Quantum genetics

- Molecular models of DNA and Molecular modelling of proteins and viruses

- Bioorganic chemistry

- Polymer chemistry

- Biochemistry and Biological chemistry

- Complex system biology

- Integrative biology

- Mathematical biophysics

- Systems biology

- Genomics, Proteomics, Interactomics, Structural bioinformatics and Cheminformatics

- Food technology, Food engineering, Food safety and Food biotechnology

- Agricultural biotechnology

- Immobilized cells and enzymes

- Microencapsulation of food additives and vitamins, etc.

- Agricultural biotechnology

- Chemical engineering

- Plant biology and Crop sciences

- Animal sciences

Techniques gallery: High-Field NMR, CARS (Raman spectroscopy), Fluorescence confocal microscopy and Hyperspectral imaging

-

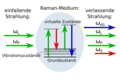

Stoks and anti-Stokes shifts

-

CARS Raman Spectroscopy

-

Hyperspectral Imaging Cube

-

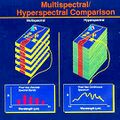

Multi-spectral Imaging principle

-

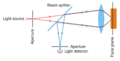

Confocal Imaging Principle

-

Fluorescence microscope

-

Yeast membrane protein imaging

-

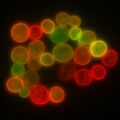

Dividing cell fluorescence

-

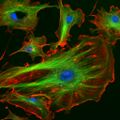

HeLa cancer cells

-

FISH fluorescence technique

-

Red blood cell pathology

-

Carboxyzome

See also

- Food chemistry

- Biophysical chemistry

- Protein–protein interactions

- Food processing

- Food engineering

- Food rheology

- Food extrusion

- Food packaging,

- food biotechnology

- Food safety

- Food science

- Food technology

- International Academy of Quantum Molecular Science

- List of important publications in chemistry § Physical chemistry

- List of unsolved problems in chemistry § Physical chemistry problems

References

- ↑ John M. de Man.1999. Principles of Food Chemistry (Food Science Text Series), Springer Science, Third Edition

- ↑ John M. de Man. 2009. Food process engineering and technology, Academic Press, Elsevier: London and New York, 1st edn.

- ↑ Pieter Walstra. 2003. Physical Chemistry Of Foods. Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, 873 pages

- ↑ Physical Chemistry Of Food Processes: Fundamental Aspects.1992. van Nostrand-Reinhold vol.1., 1st Edition,

- ↑ Henry G. Schwartzberg, Richard W. Hartel. 1992. Physical Chemistry of Foods. IFT Basic Symposium Series, Marcel Dekker, Inc.:New York, 793 pages

- ↑ Physical Chemistry of Food Processes, Advanced Techniques, Structures and Applications. 1994. van Nostrand-Reinhold vols.1-2., 1st Edition, 998 pages; 3rd edn. Minuteman Press, 2010; vols. 2-3, fifth edition (in press)

- ↑ Pieter Walstra. 2003. Physical Chemistry Of Foods. Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, 873 pages

- ↑ Pieter Walstra. 2003. Physical Chemistry Of Foods. Marcel Dekker, Inc.: New York, 873 pages

- ↑ Physical Chemistry Of Food Processes: Fundamental Aspects.1992.van Nostrand-Reinhold vol.1., 1st Edition,

- ↑ Physical Chemistry of Food Processes, Advanced Techniques, Structures and Applications.1994. van Nostrand-Reinhold vols.1-2., 1st Edition, 998 pages; 3rd edn. Minuteman Press, 2010; vols. 2-3, fifth edition (in press)

- ↑ https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1952/ First Nobel Prize for NMR in Physics, in 1952

- ↑ http://www.ismrm.org/12/aboutzavoisky.htm ESR discovery in 1941

- ↑ Abragam, A.; Bleaney, B. Electron paramagnetic resonance of transition ions. Clarendon Press:Oxford, 1970, 1,116 pages.

- ↑ Physical Chemistry of Food Processes, Advanced Techniques, Structures and Applications.1994. van Nostrand-Reinhold vols.1-2., 1st Edition, 998 pages; 3rd edn. Minuteman Press, 2010; vols. 2-3, fifth edition (in press)

- ↑ Magde D.; Elson E. L.; Webb W. W. (1972). "Thermodynamic fluctuations in a reacting system: Measurement by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, (1972)". Phys Rev Lett 29 (11): 705–708. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.29.705.

- ↑ Ehrenberg, M., Rigler, R. (1974). "Rotational brownian motion and fluorescence intensity fluctuations". Chem Phys 4 (3): 390–401. doi:10.1016/0301-0104(74)85005-6. ISSN 0301-0104. Bibcode: 1974CP......4..390E.

- ↑ Elson E. L., Magde D. (1974). "Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy I. Conceptual basis and theory, (1974)". Biopolymers 13: 1–27. doi:10.1002/bip.1974.360130102.

- ↑ Magde D.; Elson E. L.; Webb W. W. (1974). "Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy II. An experimental realization, (1974)". Biopolymers 13 (1): 29–61. doi:10.1002/bip.1974.360130103. PMID 4818131.

- ↑ Thompson N L 1991 Topics in Fluorescence Spectroscopy Techniques vol 1, ed J R Lakowicz (New York: Plenum) pp 337–78

- ↑ Gohlke, R. S. (1959). "Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry and Gas-Liquid Partition Chromatography". Analytical Chemistry 31 (4): 535–541. doi:10.1021/ac50164a024.

- ↑ Gohlke, R; McLafferty, Fred W. (1993). "Early gas chromatography/mass spectrometry". Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 4 (5): 367–71. doi:10.1016/1044-0305(93)85001-E. PMID 24234933.

Journals

- Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry

- Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society

- Biophysical Chemistry journal

- Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry

- Starke/ Starch Journal

- Journal of Dairy Science (JDS)

- Chemical Physics Letters

- Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie (1887)

- Biopolymers

- Journal of Food Science (IFT, USA)

- International Journal of Food Science & Technology

- Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics (1947)

- Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture

- Polymer Preprints (ACS)

- Integrative Biology Journal of the Royal Society of Chemistry

- Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry (An RSC Journal)

- Nature

- Nature Precedings

- Journal of Biological Chemistry

- Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

External links

- ACS Division of Agricultural and Food Chemistry (AGFD)

- American Chemical Society (ACS)

- Institute of Food Science and Technology (IFST), (formerly IFT)

- Dairy Science and Food Technology

- Physical Chemistry. (Keith J. Laidler, John H. Meiser and Bryan C. Sanctuary)

- The World of Physical Chemistry (Keith J. Laidler, 1993)

- Physical Chemistry from Ostwald to Pauling (John W. Servos, 1996)

- 100 Years of Physical Chemistry (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2004)

- The Cambridge History of Science: The modern physical and mathematical sciences (Mary Jo Nye, 2003)

|

KSF

KSF