Haloacetic acids

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 4 min

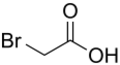

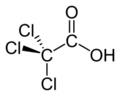

Haloacetic acids are carboxylic acids in which a halogen atom takes the place of a hydrogen atom in acetic acid. In a monohaloacetic acid, a single halogen replaces a hydrogen atom; for example, in bromoacetic acid. Further substitution of hydrogen atoms with halogens can occur, as in dichloroacetic acid and trichloroacetic acid.

The inductive effect caused by the electronegative halogens often result in the higher acidity of these compounds by stabilising the negative charge of the conjugate base.

Contaminants in treated water

Haloacetic acids (HAAs) are a common undesirable by-product of water treatment by chlorination. Exposure to such disinfection by-products in drinking water, at high levels over many years, has been associated with a number of health outcomes by epidemiological studies.[1]

HAAs can be formed following chlorination, ozonation or chloramination of water, as chlorine from the water disinfection process can react with organic matter and small amounts of bromide present in water.[2] HAAs are highly chemically stable, and therefore persist in water after formation.[3]

A study published in August 2006 found that total levels of HAAs in drinking water were not affected by storage or boiling, but that filtration was effective in decreasing levels.[4]

HAA5

In the United States, the EPA regulates the five HAAs most commonly found in drinking water, collectively referred to as "HAA5."[2] These are:

- monochloroacetic acid (MCA)

- dichloroacetic acid (DCA)

- trichloroacetic acid (TCA)

- monobromoacetic acid (MBA)

- dibromoacetic acid (DBA)

The regulation limit for these five acids combined is 60 parts per billion (ppb).[5]

HAA9

The designation "HAA9" refers to a larger group of HAAs, including all of the acids in HAA5, along with:

- bromochloroacetic acid

- bromodichloroacetic acid

- chlorodibromoacetic acid

- tribromoacetic acid

The level of these four acids in drinking water is not regulated by the EPA.[6][7]

Health Effects

Haloacetic acids are readily absorbed by the human body after being ingested, and can be absorbed slightly through the skin. At high concentrations, HAAs have irritating and corrosive properties; however, typical concentrations of HAAs found in drinking water are usually extremely low. HAAs are typically eliminated from the bodily through normal processes between 1 day and 2 weeks after ingestion, depending on the type of acid.[2]

Highly concentrated HAAs have been found to cause toxicity in various organs, including the liver and pancreas, in animal studies. This includes an increased risk of cancer, particularly of the liver and bladder. For this reason, the EPA considers a few HAAs (namely DCA and TCA) as potential human carcinogens.[2] They may also cause developmental and reproductive problems during pregnancy.[8] However, short-term adverse health effects are unlikely after ingesting dilute quantities of HAAs,[2] and the long-term low-level risks associated with drinking treated water with residual HAAs are much lower than the risks of drinking untreated water.[9]

See also

References

- ↑ "Drinking Water". http://cehtp.org/faq/drinking_water/drinking_water_contaminants_disinfection_byproducts_(dbp).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Haloacetic Acids (five) (HAA5): Health Information Summary". New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services. https://www.des.nh.gov/sites/g/files/ehbemt341/files/documents/ard-ehp-36.pdf.

- ↑ "Occurrence Assessment for the Final Stage 2 Disinfectants and Disinfection Byproducts Rule". United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://nepis.epa.gov/Exe/ZyPDF.cgi?Dockey=P1005ED2.txt.

- ↑ Levesque, S; Rodriguez, MJ; Serodes, J; Beaulieu, C; Proulx, F (2006). "Effects of indoor drinking water handling on trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids". Water Res 40 (15): 2921–30. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2006.06.004. PMID 16889815.

- ↑ "Disinfection Byproducts: A Reference Resource". United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://archive.epa.gov/enviro/html/icr/web/html/gloss_dbp.html.

- ↑ "Column Name: HAA9". United States Environmental Protection Agency. https://archive.epa.gov/enviro/html/icr/web/html/haa9.html.

- ↑ "Haloacetic acids (HAA9)". Environmental Working Group. https://www.ewg.org/tapwater/contaminant.php?contamcode=E432#.

- ↑ "Haloacetic Acids in Public Water and Health". Iowa Department of Public Health. https://tracking.idph.iowa.gov/Environment/Public-Drinking-Water/Public-Water-and-Health/HAA5-in-Public-Water-and-Health#:~:text=Haloacetic%20Acids%20are%20a%20family,substances%20in%20the%20source%20water..

- ↑ "Disinfection byproducts: HAA5" (in en-US). Minnesota Department of Health. https://data.web.health.state.mn.us/haa5-messaging.

Further reading

External links

- Haloacetic Acids (For Private Water and Health Regulated Public Water Supplies)

- "Drinking Water Contaminants – Standards and Regulations". US Environmental Protection Agency.

|

KSF

KSF