Microbead

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 17 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 17 min

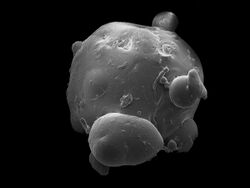

Microbeads are manufactured solid plastic particles of less than one millimeter in their largest dimension.[1] They are most frequently made of polyethylene but can be of other petrochemical plastics such as polypropylene and polystyrene. They are used in exfoliating personal care products, toothpastes, and in biomedical and health-science research.[2]

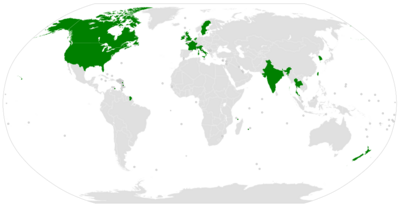

Microbeads can cause plastic particle water pollution and pose an environmental hazard for aquatic animals in freshwater and ocean water. In the United States, the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015 phased out microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics by July 2017.[3] Several other countries have also banned microbeads from rinse-off cosmetics, including Canada, France, New Zealand, Sweden, Taiwan, and the United Kingdom.

Types

Microbeads are manufactured solid plastic particles of less than one millimeter in their largest dimension[4] when they are first created, and are typically created using material such as polyethylene (PE), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), nylon (PA), polypropylene (PP), and polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA).[5] The most frequently used materials are polyethylene or other petrochemical plastics such as polypropylene and polystyrene.[6][7] Microbeads are commercially available in particle sizes from 10 micrometres (0.00039 in) to 1 millimetre (0.039 in).[8] Low melting temperature and fast phase transitions make them especially suitable for creating porous structures in ceramics and other materials.[9]

Regional differences

The parameters for what qualifies as a microbead change subtly based on location and the corresponding legal jurisdiction; minor distinctions in the definition may be encountered from one country to another.[10] For example, the U.S. official definition for a microbead, as per the Microbead-Free Waters Act 2015 laid out by Congress, is "any solid plastic particle less than 5 millimeters in size that was created with the intention of being used to exfoliate or cleanse the human body."[11] On the other hand, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), the governmental agency responsible for Canada's microbead ban, settled on a definition which includes only plastics with diameters between 0.5 microns and 2 millimeters; although a diameter range of 0.1 microns to 5 millimeters was initially proposed, the definition was revised after consultation with members of industry and meeting resistance from plastic manufacturers who claimed that many of their raw materials (for example, those needed to make bottles for soft drinks) would be covered by the ban, affecting their business unduly.[10][12] While the intent clause in the American law leaves open a loophole for producers of other equally frivolous and environmentally destructive products to potentially exploit in the future—as long as their use case does not involve grooming or personal care—the Canadian law has already been criticized publicly for its overly restrictive nature, which could cripple its efficacy in practice; in response to the revised definition, concerned conservation groups (including the Sierra Club of Canada) have raised warnings about the law's wording, fearing that Canada may "become a dumping ground for [those] microbead-containing products" which are now banned in the United States.[10]

Use

Microbeads are added as an exfoliating agent to cosmetics and personal care products, such as soap, facial scrub, and toothpastes.[13] They may be added to over-the-counter drugs to make them easier to swallow.[14] In biomedical and health science research, microbeads are used in microscopy techniques, fluid visualization, fluid flow analysis, and process troubleshooting.[15][16]

Sphericity and particle size uniformity create a ball-bearing effect in creams and lotions, resulting in a silky texture and spreadability. Smoothness and roundness can provide lubrication. Colored microspheres add visual appeal to cosmetic products.[17]

Environmental effects

When microbeads are washed down the drain, they subsequently pass unfiltered through sewage treatment plants and make their way into rivers and canals, resulting in plastic particle water pollution.[18] The beads can absorb and concentrate pollutants like pesticides and polycyclic hydrocarbons.[13][19] Microbeads have been found to pollute the Great Lakes in high concentrations, particularly Lake Erie. A study from the State University of New York, found anywhere from 1,500 to 1.1 million microbeads per square mile on the surface of the Great Lakes.[20]

One study suggested that environmentally relevant levels of polyethylene microbeads had no impact on larvae.[21] Some wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in the U.S. and Europe can remove microbeads with an efficiency of greater than 98%, others may not.[22][23] As such, other sources of microplastic pollution (e.g. microfibers/fibers and car tires) are more likely to be associated with environmental hazards.[24]

A variety of wildlife, from insect larvae, small fish, amphibians and turtles to birds and larger mammals, mistake microbeads for their food source. This ingestion of plastics introduces the potential for toxicity not only to these animals but to other species higher in the food chain.[25][26] Harmful chemicals thus transferred can include hydrophobic pollutants that collect on the surface of the water such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).[27]

Because the negative impacts of microbeads are a recent discovery, there is still debate about the extent to which they harm various marine life. Despite this uncertainty in the scientific community, there is widespread consensus that microbeads are harmful to marine life. Current methods for cleaning microplastics from the ocean are inefficient, unscalable, and economically infeasible, which serves to intensify the harms they pose.[28] Because their lifespan cannot easily be reduced, the current best method to reduce pollution is to invest in their prohibition.

Banning production and sale in cosmetics

In 2012, the North Sea Foundation and the Plastic Soup Foundation launched an app allowing Dutch consumers to check whether personal care products contain microbeads.[29] In the summer of 2013, the United Nations Environment Programme and UK-based NGO Fauna and Flora International joined the partnership to further develop the app for international audiences. The app has enjoyed success, convincing a number of large multinationals to stop using microbeads,[30] and is available in seven languages. There are many natural and biodegradable alternatives to microbeads that have no environmental impact when washed down the drain, as they will either decompose or get filtered out before being released into the natural environment. Some examples to use as natural exfoliates include ground-up almonds, oatmeal, sea salt, and coconut husks.[31] Burt's Bees and St. Ives use apricot pits and cocoa husks in its products instead of microbeads to reduce their negative environmental impact.[32]

Due to the increase in bans of microbeads in the United States, many cosmetic companies had also been phasing out microbeads from their production lines.[33] L'Oréal had phased out polyethylene microbeads in the exfoliates, cleansers and shower gels from its products by 2017.[34] Johnson and Johnson, who had already started to phase out microbeads at the end of 2015, had stopped producing polyethylene microbeads in their products by 2017.[35] Lastly, Crest had phased out microbeads in its toothpastes in the U.S. by February 2016, and globally by 2017.[36]

The following countries have taken action towards ban on microbeads.

| State | Sales ban effective date | Scope |

|---|---|---|

| 29 December 2022 | Ban on import, manufacture, and sale of microbeads in cosmetics.[37] | |

| 1 January 2018 | Ban on microbeads smaller than 5 mm in size. | |

| 31 December 2022 | Ban on sale, following a ban on production two years earlier (31 December 2020).[38] | |

| 1 January 2018 | Ban on import, manufacture, and sale of microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics.[39] | |

| 20 February 2020 | Ban on microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics.[40] | |

| 1 January 2020 | Ban on microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics.[41][42] | |

| 7 June 2018 | Ban on import, manufacture, and sale of microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics.[43] | |

| 1 July 2017 | Ban on sale of microbeads in cosmetics.[44] | |

| 1 January 2019 | Ban on sale of microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics, following an earlier ban on import and manufacture (1 July 2018).[45] | |

| 1 July 2018 | Ban on sale of microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics, following an earlier ban on import and manufacture (1 January 2018).[46] | |

| 1 January 2020 | Ban on import, manufacture, and sale of microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics.[47] | |

| 1 October 2018 | Ban on the use of microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics and personal care products. England and Scotland (19 June 2018), Wales (30 June 2018), Northern Ireland (1 October 2018). | |

| 1 July 2017 | Ban on manufacture of microbeads for rinse-off cosmetics at the federal level. |

Australia

In 2016, the federal and state governments agreed to support a voluntary industry phase-out of microbeads in rinse-off personal care, cosmetic, and cleaning products. An independent assessment in 2020 found that more than 99% of products it inspected were microbead-free.[48] The New South Wales state government banned the supply of rinse-off personal care products containing microbeads, effective from 1 November 2022.[49]

Canada

On May 18, 2015, Canada took its first steps toward banning microbeads when a Member of Parliament from Toronto, John McKay, introduced Bill C-680, which would ban the sale of microbeads.[50] The first Canadian province to take action against microbeads was Ontario, where Maire-France Lalonde, a Member of the Provincial Parliament, introduced the Microbead Elimination and Monitoring Act.[51] This bill enforced the ban of manufacturing microbeads in cosmetics, facial scrubs or washes, and similar products. The bill also proposed that there would be yearly samples taken from the Canadian Great Lakes, which would be analyzed for traces of microbeads.[51]

Pointe-Claire mayor Morris Trudeau and members of the City Council requested Pointe-Claire residents to sign a petition asking governments of Canada and Quebec to ban "the use of plastic microbeads in cosmetic and cleansing products." Trudeau suggested that if Quebec banned microbeads, manufactures would be encouraged to stop producing them in their products.[52] Megan Leslie, Halifax Member of Parliament, presented a motion against microbeads in the House of Commons, which received "unanimous support" and was hoping for them to be listed under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act as a toxin.[53]

On June 29, 2016, the Federal Government of Canada added microbeads in the Canadian Environmental Protection Act under Schedule 1 as a toxic substance.[33][54] The import or manufacture of toiletries containing microbeads was banned on January 1, 2018, and sales were banned from July 1, 2018.[55][56] Microbeads in natural health products and non-prescription drugs were also banned in 2019.[57][33]

Ireland

In November 2016, Simon Coveney, the Minister for Housing, Planning, Community and Local Government, said that the Fine Gael–led government would press for an EU-wide ban on microbeads and rejected a Green Party bill banning them on the basis that it might conflict with the EU's freedom of movement of goods.[58][59] In June 2019, Coveney's successor Eoghan Murphy introduced the Microbeads (Prohibition) Bill 2019, which would ban manufacture, sale, and export of rinse-off microbead products.[60] The government also intends to include microbeads when updating the law on preventing marine pollution.[59][61] Microbeads were banned in February 2020.[40]

Netherlands

The Netherlands was the first country to announce its intent to be free of microbeads in cosmetics by the end of 2016.[62] State Secretary for Infrastructure and the Environment Mansveld has said she is pleased with the progress made by the members of the Nederlandse Cosmetica Vereniging (NCV), the Dutch trade organisation for producers and importers of cosmetics,[63] who have ceased using microbeads or are working towards removing microbeads from their product. Among the NCV's members are large multinationals such as Unilever, L'Oréal, Colgate-Palmolive, Henkel, and Johnson & Johnson.[citation needed]

South Africa

A ban on microbeads has been proposed in South Africa after microplastic pollution was found in tap water.[64]

United Kingdom

The British government has banned the production of microbeads in rinse-off cosmetics and cleaning products in England[65] effective 9 January 2018,[66] followed by a sales ban on 19 June 2018.[67][68] Scotland introduced its own manufacture and sales ban on the same day[69][68] and Wales introduced its on 30 June 2018.[70] The ban was extended to Northern Ireland from 11 March 2019.[71]

United States

National

At the federal level, the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015 prohibits the manufacture and introduction into interstate commerce of rinse-off cosmetics containing intentionally-added plastic microbeads by July 1, 2017. Representative Frank Pallone proposed the bill in 2014 (H.R. 4895, reintroduced in 2015 as H.R. 1321). On December 7, 2015, his proposal was narrowed by amendment to rinse-off cosmetics, and passed unanimously by the House.[72] The American Chemistry Council and other industry groups supported the final bill,[13][73][74] which the Senate passed on December 18, 2015, and the president signed on December 28, 2015.[72] Since the act took effect, the use of microbeads in toothpaste and other rinse-off cosmetic products has been discontinued in the U.S.;[75] however, since 2015, many industries have instead shifted toward using FDA-approved "rinse-off" metallized-plastic glitter as their primary abrasive agent.[76][77][78]

States

Illinois became the first U.S. state to enact legislation banning the manufacture and sale of products containing microbeads; the two-part ban went into effect in 2018 and 2019.[79] The Personal Care Products Council, a trade group for the cosmetics industry, came out in support of the Illinois bill.[80] Other states have followed.

(As of October 2015), all state bans except California's ban, had allowed biodegradable microbeads.[81][82] Johnson & Johnson and Procter & Gamble opposed the California law.[83]

| State/territory | Date enacted | Effective date | Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| October 8, 2015[83] | January 1, 2018 (manufacture of personal care products) – Jan. 1, 2020 (sale of over-the-counter drugs) | Restricted to rinse-off cosmetics that contain more than 1 ppm of microbeads. Does not allow biodegradable microbeads.[82][84] | |

| March 26, 2015 | Jan. 1, 2018 (manufacture of personal care products) – Jan. 1, 2020 (sale of over-the-counter drugs)[85] | Restricted to rinse-off cosmetics. Allows biodegradable microbeads. | |

| June 30, 2015 | Jan. 1, 2018 (manufacture of personal care products) – Jan. 1, 2020 (sale of over-the-counter drugs)[86] | Restricted to rinse-off cosmetics. Allows biodegradable microbeads. | |

| June 8, 2014[87] | Jan. 1, 2018 (manufacture of personal care products) – Jan. 1, 2020 (sale of over-the-counter drugs)[88] | Restricted to rinse-off cosmetics. Allows biodegradable microbeads. Excludes prescription drugs. | |

| April 15, 2015 | Jan. 1, 2018 (manufacture of personal care products) – Jan. 1, 2020 (sale of over-the-counter drugs) | Restricted to rinse-off cosmetics. Allows biodegradable microbeads.[89] | |

| March 2015 | Jan. 1, 2018 (manufacture of personal care products) – Jan. 1, 2020 (sale of over-the-counter drugs) | Restricted to rinse-off cosmetics. Allows biodegradable microbeads. | |

| May 12, 2015 | Jan. 1, 2018 (manufacture of personal care products) – Jan. 1, 2020 (sale of over-the-counter drugs)[90] | Restricted to rinse-off cosmetics. Allows biodegradable microbeads. | |

| March 2015[91][92] | Jan. 1, 2018 (manufacture of personal care products) – Jan. 1, 2020 (sale of over-the-counter drugs)[93] | Restricted to rinse-off cosmetics. Allows biodegradable microbeads.[94] | |

| July 1, 2015[95] | January 1, 2018 (manufacture of personal care products) – Jan. 1, 2020 (sale of over-the-counter drugs) | Restricted to rinse-off cosmetics. Allows biodegradable microbeads. Excludes prescription drugs. |

In 2014, legislation was voted on but failed to pass in New York.[96]

Local

In 2015, Erie County, New York, passed the first local ban in the state of New York. It banned the sale and distribution of all plastic microbeads (including biodegradable ones) including from personal care products.[97] (As of September 2015), its prohibition on sales was stronger than any other law in the country.[98] It was enacted on August 12, 2015,[99] and took effect in February 2016.[100]

In November 2015, four other NY counties followed suit.[101]

See also

- Cenosphere

- Expandable microsphere

- Glass microsphere

- Microplastics

- Glitter

- Nurdle (bead)

- Plastic particle water pollution

References

- ↑ Arthur et al. (eds.). 2009. Proceedings of the International Research Workshop on the Occurrence, Effects, and Fate of Microplastic Marine Debris. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Technical Memorandum. NOS-OR&R-30

- ↑ "Microbeads, Meal kits, You and Yours - BBC Radio 4". http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07lfkq2.

- ↑ "H.R.1321 - Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015". Congress.gov. 28 December 2015. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1321.

- ↑ Imam, Jareen (19 September 2015). "8 trillion microbeads pollute U.S. aquatic habitats daily". CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2015/09/19/us/8-trillion-microbeads-pollute-water-daily-irpt/index.html.

- ↑ "Microbeads – A Science Summary July 2015". https://www.ec.gc.ca/ese-ees/ADDA4C5F-F397-48D5-AD17-63F989EBD0E5/Microbeads_Science%20Summary_EN.pdf.

- ↑ "Microbeads". 5 Gyres. http://www.5gyres.org/microbeads/.

- ↑ "Microbeads – A Science Summary". Environment Canada. July 2015. http://www.ec.gc.ca/ese-ees/default.asp?lang=En&n=ADDA4C5F-1.

- ↑ Graham, Karen (2017-09-07). "Removing microplastics from tap water starts at treatment plants". http://www.digitaljournal.com/tech-and-science/technology/removing-microplastics-from-tap-water-starts-at-treatment-plants/article/501870.

- ↑ Liu, P.S.; Chen, G.F. (2014). "Producing Polymer Foams". Porous Materials. pp. 345–382. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-407788-1.00007-1. ISBN 978-0-12-407788-1.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Microbeads: "Tip of the Toxic Plastic-berg"? Regulation, Alternatives, and Future Implications". https://issp.uottawa.ca/sites/issp.uottawa.ca/files/microbeads_-_literature_review_2.pdf.

- ↑ "Text – H.R.1321 – 114th Congress (2015–2016): Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015". 28 December 2015. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1321/text.

- ↑ "Microbeads – A Science Summary July 2015". https://www.ec.gc.ca/ese-ees/ADDA4C5F-F397-48D5-AD17-63F989EBD0E5/Microbeads_Science%20Summary_EN.pdf.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Danny Lewis (10 December 2015). "Five Things to Know About Congress' Vote to Ban Microbeads". Smithsonian magazine. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/five-things-know-about-congress-vote-ban-microbeads-180957501/.

- ↑ Snead, Florence (2018-06-19). "The products with microbeads you will no longer be able to buy from today" (in en-GB). https://inews.co.uk/news/environment/plastic-microbead-ban-products-you-wont-be-able-to-buy/.

- ↑ "Opaque Polyethylene Microspheres for Coatings Applications". http://www.pcimag.com/Articles/Feature_Article/BNP_GUID_9-5-2006_A_10000000000000723862.

- ↑ Kieler, Ashlee (2015-12-29). "Say Goodbye To Microbeads: President Signs Act To Ban Microscopic Plastic Particles". https://consumerist.com/2015/12/29/say-goodbye-to-microbeads-president-signs-act-to-ban-microscopic-plastic-particles/.

- ↑ Solid Polyethylene Microspheres for effects in color cosmetics Cosmetics and Toiletries.com, April 2010

- ↑ Fendall, L.S.; Sewell, M.A. (2009). "Contributing to marine pollution by washing your face: microplastics in facial cleansers". Marine Pollution Bulletin 58 (8): 1225–1228. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.04.025. PMID 19481226.

- ↑ Johnston, Christopher (June 25, 2013). "Personal Grooming Products May Be Harming Great Lakes Marine Life.". http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/microplastic-pollution-in-the-great-lakes/.

- ↑ "Plastic microbeads pile up into problems for the Great Lakes". 30 July 2014. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/tiny-plastic-microbeads-pile-problems-great-lakes/.

- ↑ Kaposi, Katrina L.; Mos, Benjamin; Kelaher, Brendan P.; Dworjanyn, Symon A. (4 February 2014). "Ingestion of Microplastic Has Limited Impact on a Marine Larva". Environmental Science & Technology 48 (3): 1638–1645. doi:10.1021/es404295e. PMID 24341789. Bibcode: 2014EnST...48.1638K.

- ↑ Murphy, Fionn; Ewins, Ciaran; Carbonnier, Frederic; Quinn, Brian (7 June 2016). "Wastewater Treatment Works (WwTW) as a Source of Microplastics in the Aquatic Environment". Environmental Science & Technology 50 (11): 5800–5808. doi:10.1021/acs.est.5b05416. PMID 27191224. Bibcode: 2016EnST...50.5800M. https://myresearchspace.uws.ac.uk/ws/files/262183/160418_Waste_Water_Treatment_Works_WwTW_as_a_Source_of_Microplastics_in_the_Aquatic_Environment.pdf.

- ↑ Carr, Steve A.; Liu, Jin; Tesoro, Arnold G. (March 2016). "Transport and fate of microplastic particles in wastewater treatment plants". Water Research 91: 174–182. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2016.01.002. PMID 26795302.

- ↑ Lea, Robert (2021-01-13). "The True Extent of Microplastic Pollution Caused by Clothing Revealed" (in en). https://www.azocleantech.com/news.aspx?newsID=28642.

- ↑ Gunawardana, Maleesha. "The Macro Problems of Microbeads In Sri Lankan Seas" (in en). https://roar.media/english/life/environment-wildlife/the-macro-problems-of-microbeads.

- ↑ Hettiarachchi, Dineshani (13 June 2020). "Microplastics – The silent killer". http://www.themorning.lk/microplastics-the-silent-killer/.

- ↑ Nalbone, Jennifer; Schneiderman, Eric T; Srolovic, Lemuel M (2014). Unseen threat: how microbeads harm New York waters, wildlife, health and environment. Office of the Attorney General. OCLC 927110175. https://nysl.ptfs.com/data/Library1/Library1/pdf/927110175.pdf.

- ↑ Pan, Yusheng; Gao, Shu-Hong; Ge, Chang; Qun, Gao; Huang, Sijing; Kang, Yuanyuan; Luo, Gaoyang; Zhang, Ziqi et al. (13 Jan 2023). "Removing microplastics from aquatic environments: A critical review". Environmental Science and Ecotechnology. doi:10.1016/j.ese.2022.100222. PMID 36483746. PMC 9722483. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9722483/. Retrieved 24 Jan 2024.

- ↑ "In short - Beat the Microbead". Beat the Microbead. http://www.beatthemicrobead.org/en/in-short.

- ↑ "Results - Beat the Microbead". Beat the Microbead. http://www.beatthemicrobead.org/en/results.

- ↑ "Micro plastics in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Region.". June 4, 2015. http://glslcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Microbeads-Fact-Sheet_June-2015.pdf.

- ↑ "Facial scrubs polluting Great Lakes with plastic". July 31, 2013. http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/thunder-bay/facial-scrubs-polluting-great-lakes-with-plastic-1.1327850.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Xanthos, Dirk; Walker, Tony Himani R. (May 2017). "International policies to reduce plastic marine pollution from single-use plastics (plastic bags and microbeads): A review". Marine Pollution Bulletin 118 (1–2): 17–26. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.02.048. PMID 28238328.

- ↑ "L'oread commits to phase out all polyethylene microbeads from its scrubs by 2017.". January 29, 2014. http://www.loreal.com/media/news/2014/jan/l'oréal-commits-to-phase-out-all-polyethylene-microbeads-from-its-scrubs-by-2017.

- ↑ "Microbeads". Johnson and Johnson. December 10, 2016. http://www.safetyandcarecommitment.com/ingredient-info/other/microbeads.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions About Microbeads". August 23, 2014. http://crestfaq.tumblr.com.

- ↑ Havens, Raissa. "Argentina Prohibits Plastic Microbeads in Cosmetic Products". https://msc.ul.com/en/resources/article/argentina-prohibits-plastic-microbeads-in-cosmetic-products/.

- ↑ "China to ban production of cosmetics containing microbeads by 2020 end". 5 December 2019. https://www.globalcosmeticsnews.com/china-to-ban-production-of-cosmetics-containing-microbeads-by-2020-end/.

- ↑ "France to ban microplastics in some cosmetics products". https://chemicalwatch.com/50368/france-to-ban-microplastics-in-some-cosmetics-products.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "Green News Ireland is under construction". https://greennews.ie/microbead-law-ireland/.

- ↑ "Italy to ban microplastics used in rinse-off cosmetics products". https://chemicalwatch.com/67533/italy-to-ban-microplastics-used-in-rinse-off-cosmetics-products?q=microbead.

- ↑ "Ban on microbeads in UK, Italy and New Zealand - Beat the Microbead". 22 December 2017. https://www.beatthemicrobead.org/ban-on-microbeads-in-uk-italy-and-new-zealand/.

- ↑ "Plastic microbeads ban - Ministry for the Environment". http://www.mfe.govt.nz/waste/plastic-microbeads.

- ↑ "Korea Bans Plastic Microbeads in Cosmetics". 2017-07-04. https://cosmetic.chemlinked.com/news/cosmetic-news/korea-bans-plastic-microbeads-cosmetics.

- ↑ "Sweden adopts microbeads ban in rinse-off cosmetics". https://chemicalwatch.com/63737/sweden-adopts-microbeads-ban-in-rinse-off-cosmetics.

- ↑ "Taipei brings forward microbeads ban". https://chemicalwatch.com/asiahub/58391/.

- ↑ "Thailand's plastic ban prompts producers to be eco-friendly". https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Business-trends/Thailand-s-plastic-ban-prompts-producers-to-be-eco-friendly.

- ↑ "Plastic microbeads". 11 October 2021. https://www.dcceew.gov.au/environment/protection/waste/plastics-and-packaging/plastic-microbeads#2020-independent-microbead-assessment.

- ↑ "Microbeads". 1 June 2022. https://www.epa.nsw.gov.au/your-environment/waste/reducing-your-household-waste/what-are-microbeads.

- ↑ "Bill C-680". http://www.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?Language=E&Mode=1&DocId=7983635.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Lalonde, Maire-France. "Bill 75, Microbead Elimination and Monitoring Act, 2015". http://www.ontla.on.ca/web/bills/bills_detail.do?locale=en&BillID=3194&detailPage=bills_detail_debates.

- ↑ "Pointe-Claire asks for a ban on plastic microbeads". September 11, 2015. http://www.pointe-claire.ca/en/information-city-of-pointe.html.

- ↑ Windsor, Hillary (April 16, 2015). "Megan Leslie wants a ban on microbeads.". http://www.thecoast.ca/halifax/megan-leslie-wants-a-ban-on-microbeads/Content?oid=4601345.

- ↑ "Statement by Environmental Defence's Maggie MacDonald on federal government's decision on microbeads - Environmental Defence". 29 June 2016. http://environmentaldefence.ca/2016/06/29/statement-environmental-defences-maggie-macdonald-federal-governments-decision-microbeads/.

- ↑ "Canada Has Officially Banned Toiletries That Contain Plastic Microbeads". https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/canada-bans-microbeads/.

- ↑ "Canadian government moves to ban plastic microbeads in toiletries by July 2018". 4 November 2016. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2016/11/04/canadian-government-moves-to-ban-plastic-microbeads-in-toiletries-by-july-2018.html.

- ↑ Pettipas, Shauna; Bernier, Meagan; Walker, Tony R. (June 2016). "A Canadian policy framework to mitigate plastic marine pollution". Marine Policy 68: 117–122. doi:10.1016/j.marpol.2016.02.025.

- ↑ "Written answers: Environmental Policy". 16 November 2016. https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2016-11-16a.312.; "Seanad debates: Micro-plastic and Micro-bead Pollution Prevention Bill 2016: Second Stage". 23 November 2016. https://www.kildarestreet.com/sendebates/?id=2016-11-23a.523.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Kiernan, Eddie (2016-11-23). "Minister Coveney addresses the Green Party's Private Members Bill on Microbeads". Department of Housing, Planning, Community and Local Government (Press release). Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- ↑ "Ireland to be first EU country to ban plastic microbeads in cleaners, Dáil told". Irish Times. 20 June 2019. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/politics/oireachtas/ireland-to-be-first-eu-country-to-ban-plastic-microbeads-in-cleaners-d%C3%A1il-told-1.3932542.; "Microbeads (Prohibition) Bill 2019 – No. 41 of 2019" (in en-ie). Oireachtas. 14 June 2019. https://www.oireachtas.ie/en/bills/bill/2019/41/?tab=debates.

- ↑ "Written answers: Maritime Spatial Planning". 20 June 2018. https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id=2018-06-20a.530.

- ↑ "Beat the Microbead: Nederland spreekt zich uit" (in NL). Plastic Soup Foundation. October 29, 2014. http://plasticsoupfoundation.org/nieuws/beat-the-microbead-nederland-spreekt-zich-uit/.

- ↑ "Appreciatie RIVM rapport en stand van zaken microplastics en geneesmiddelen". Rijksoverheid. October 28, 2014. https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/kst-27625-329.html.

- ↑ "Government considering ban on microbeads after Gauteng drinking water is found to be contaminated". https://www.news24.com/SouthAfrica/News/government-considering-ban-on-microbeads-after-gauteng-drinking-water-is-found-to-be-contaminated-20180809.

- ↑ "The Environmental Protection (Microbeads) (England) Regulations 2017". http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2017/1312/contents/made.

- ↑ "Plastic microbeads ban enters force in UK". The Guardian. 9 January 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/jan/09/plastic-microbeads-ban-enters-force-in-uk.

- ↑ "Face scrubs and toothpastes hit as ban on microbeads begins". https://news.sky.com/story/face-scrubs-and-toothpastes-hit-as-ban-on-microbeads-begins-11409212.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 "World leading microbeads ban comes into force". https://www.gov.uk/government/news/world-leading-microbeads-ban-comes-into-force.

- ↑ "Scotland announces microbeads ban". https://chemicalwatch.com/63809/scotland-announces-microbeads-ban.

- ↑ "Wales to ban microbeads from June". https://chemicalwatch.com/63541/wales-to-ban-microbeads-from-june.

- ↑ "The Environmental Protection (Microbeads) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2019". UK Government. 11 July 2018. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/nisr/2019/18/made.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 "Statement by the Press Secretary on H.R. 1321, S. 2425". whitehouse.gov. 2015. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2015/12/28/statement-press-secretary-hr-1321-s-2425.

- ↑ Kari, Embree (2015-12-08). "U.S. House passes legislation to ban plastic microbeads". http://www.plasticstoday.com/articles/us-house-passes-legislation-to-ban-plastic-microbeads-151208.

- ↑ "H.R.1321 - To amend the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to prohibit the manufacture and introduction or delivery for introduction into interstate commerce of rinse-off cosmetics containing intentionally-added plastic microbeads.". Congress.gov. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/1321/.

- ↑ "What Are Microbeads In Toothpaste?". Colgate. https://www.colgate.com/en-us/oral-health/brushing-and-flossing/what-are-microbeads-in-toothpaste.

- ↑ Caity Weaver (December 21, 2018). "What Is Glitter? A strange journey to the glitter factory.". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/21/style/glitter-factory.html.

- ↑ Trisha Bartle (October 17, 2022). "TikTok Is Going Deep On The Glitter Conspiracy Theories–Is It Toothpaste, Boats, Or Something Else?". Collective World. https://collective.world/tiktok-is-going-deep-on-the-glitter-conspiracy-theories-is-it-toothpaste-boats-or-something-else/.

- ↑ Beccy Corkill (December 21, 2022). "The Glitter Conspiracy Theory: Who Is Taking All Of The Glitter?". IFLScience. https://www.iflscience.com/the-glitter-conspiracy-theory-who-is-taking-all-of-the-glitter-66761.

- ↑ "Governor Quinn Signs Bill to Ban Microbeads, Protect Illinois Waterways". Illinois Government News Network. June 8, 2014. http://www3.illinois.gov/PressReleases/ShowPressRelease.cfm?SubjectID=2&RecNum=12313.

- ↑ Johnson, Jim (May 9, 2014). "Momentum building for plastic microbead bans". Plastics News. http://www.plasticsnews.com/article/20140509/NEWS/140509903/momentum-building-for-plastic-microbead-bans.

- ↑ Paul Rogers (9 October 2015) Plastic microbeads and state coal investments banned as Gov. Jerry Brown signs new laws East Bay Times.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Phil Willon California lawmakers approve ban on plastic microbeads LA Times, 8 September 2015

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Mason, Melanie (October 8, 2015). "Products with plastic microbeads to be banned under new California law". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/local/political/la-me-pc-plastic-microbeads-ban-20151008-story.html.

- ↑ California Lawmakers Approve Ban On Plastic Microbeads In Cosmetics Lydia O'Connor, The Huffington Post,8 September 2015

- ↑ "HOUSE BILL 15-1144". State of Colorado. http://www.leg.state.co.us/clics/clics2015a/csl.nsf/billcontainers/98235FBAF6C0BC3387257DC70059AA2A/$FILE/1144_ren.pdf.

- ↑ "Bill No. 1502". State of Connecticut. http://cga.ct.gov/2015/TOB/S/2015SB-01502-R00-SB.htm.

- ↑ "Governor Quinn Signs Bill to Ban Microbeads, Protect Illinois Waterways". State of Illinois. June 8, 2014. http://www3.illinois.gov/PressReleases/ShowPressRelease.cfm?SubjectID=2&RecNum=12313.

- ↑ "Microbead-free waters". Illinois General Assembly. http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/documents/041500050K52.5.htm.

- ↑ "HOUSE ENROLLED ACT No. 1185". State of Indiana. https://iga.in.gov/legislative/2015/bills/house/1185#document-8b918881.

- ↑ "House Bill 216". State of Maryland. http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2015RS/fnotes/bil_0006/hb0216.pdf.

- ↑ Johnson, Brent (24 October 2014). "Bill to ban microbeads in N.J. heads to Christie's desk". NJ Advance media for NJ.com. http://www.nj.com/politics/index.ssf/2014/10/bill_to_ban_microbeads_in_nj_heads_to_christies_desk.html.

- ↑ Sergio Bichao (March 23, 2015). "Products with microbeads will disappear from N.J. stores thanks to new ban". Mycentarlnewjersey.com (Gannett). http://www.mycentraljersey.com/story/news/local/new-jersey/2015/03/23/products-microbeads-will-disappear-nj-stores-thanks-new-ban/70338692/.

- ↑ "ASSEMBLY, No. 3083". State of New Jersey. 2014. http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2014/Bills/A3500/3083_I1.HTM.

- ↑ "CHAPTER 28". New Jersey Office of Legislative Services. http://www.njleg.state.nj.us/2014/Bills/PL15/28_.HTM.

- ↑ O'Brien, Brendan (July 1, 2015). "Wisconsin Governor Walker signs bill banning microbeads". Reuters. https://news.yahoo.com/wisconsin-governor-walker-signs-bill-banning-microbeads-002857108--sector.html.

- ↑ Abrams, Rachel (May 22, 2015). "Fighting Pollution From Microbeads Used in Soaps and Creams". New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/23/business/energy-environment/california-takes-step-to-ban-microbeads-used-in-soaps-and-creams.html.

- ↑ "Local Law #3, 2015". Erie County. 2015. http://www2.erie.gov/legislature/sites/www2.erie.gov.legislature/files/uploads/Session_Folders/2015/Session_17/Local%20Law%20No.3%202015.PDF.

- ↑ Warner, Gene (11 August 2015). "Consumers, companies prepare for Erie County microbead ban". The Buffalo News. http://www.buffalonews.com/city-region/erie-county/consumers-companies-prepare-for-erie-county-microbead-ban-20150811.

- ↑ "Law signed to ban microbeads in Erie County". WGRZ.com. August 12, 2015. http://www.wgrz.com/story/news/2015/08/12/law-signed-to-ban-microbeads-in-erie-county/31575995/.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Erie County Appears To Be Not Fully Enforcing Microbead Ban". http://spectrumlocalnews.com/nys/buffalo/politics/2016/05/5/microbead-ban.

- ↑ "Microbeads to no longer be sold in Albany Co.". News 10. November 9, 2015. http://news10.com/2015/11/09/microbeads-to-no-longer-be-sold-in-albany-co/.

External links

|

KSF

KSF