Psychedelic drug

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 36 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 36 min

| Psychedelic | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

Chemical structure of psilocybin, the main active constituent of psilocybin-containing mushrooms and one of the most well-known serotonergic psychedelics. | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Serotonergic psychedelic; Classical psychedelic; Classical hallucinogen; Serotonergic hallucinogen; Psychotomomimetic; Entheogen |

| Use | Recreational, spiritual, medical, microdosing |

| Mechanism of action | Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonism |

| Biological target | Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor |

| Chemical class | Tryptamines; Phenethylamines; Lysergamides; Others |

| Part of a series on |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

Psychedelics are a subclass of hallucinogenic drugs whose primary effect is to trigger non-ordinary mental states (known as psychedelic experiences or "trips") and a perceived "expansion of consciousness".[1][2] Also referred to as classic hallucinogens or serotonergic hallucinogens, the term psychedelic is sometimes used more broadly to include various other types of hallucinogens as well, such as those which are atypical or adjacent to psychedelia like salvia and MDMA, respectively.[3]

Classic psychedelics generally cause specific psychological, visual, and auditory changes, and oftentimes a substantially altered state of consciousness.[4][5][6][7] They have had the largest influence on science and culture, and include mescaline, LSD, psilocybin, and DMT.[8][9] There are a large number of both naturally occurring and synthetic serotonergic psychedelics.[10][11]

Most psychedelic drugs fall into one of the three families of chemical compounds: tryptamines, phenethylamines, or lysergamides. They produce their psychedelic effects by binding to and activating a receptor in the brain called the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, and hence are a type of serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonist.[1][12][13][5][3] By activating serotonin 5-HT2A receptors,[14] they modulate the activity of key circuits in the brain involved with sensory perception and cognition. However, the exact nature of how psychedelics induce changes in perception and cognition via the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor is still unknown.[15] The psychedelic experience is often compared to non-ordinary forms of consciousness such as those experienced in meditation,[16][2] mystical experiences,[7][6] and near-death experiences,[6] which also appear to be partially underpinned by altered default mode network activity.[17] The phenomenon of ego death is often described as a key feature of the psychedelic experience.[16][2][6]

Many psychedelic drugs are illegal to possess without lawful authorisation, exemption or license worldwide under the UN conventions, with occasional exceptions for religious use or research contexts. Despite these controls, recreational use of psychedelics is common.[18][19] There is also a long history of use of naturally occurring psychedelics as entheogens dating back thousands of years. Legal barriers have made the scientific study of psychedelics more difficult. Research has been conducted, however, and studies show that psychedelics are physiologically safe and rarely lead to addiction.[20][21] Studies conducted using psilocybin in a psychotherapeutic setting reveal that psychedelic drugs may assist with treating depression, anxiety, alcohol addiction, and nicotine addiction.[5][22] Although further research is needed, existing results suggest that psychedelics could be effective treatments for certain mental health conditions.[23][24][25][19] A 2022 survey by YouGov found that 28% of Americans had used a psychedelic at some point in their life.[26]

Examples

- LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) is a derivative of lysergic acid, which is obtained from the hydrolysis of ergotamine. Ergotamine is an alkaloid found in the fungus Claviceps purpurea (ergot), which primarily infects rye. LSD is both the prototypical psychedelic and the prototypical lysergamide. As a lysergamide, LSD contains both a tryptamine and phenethylamine group within its structure. Uniquely among psychedelics, LSD agonises dopamine receptors as well as serotonin receptors.[27][28]

- Psilocin (4-HO-DMT) is the dephosphorylated active metabolite of the indole alkaloid psilocybin and a substituted tryptamine, which is produced by hundreds of species of psilocybin-containing mushrooms. Of the classical psychedelics, psilocybin has attracted the greatest academic interest regarding its ability to manifest mystical experiences,[29] although all psychedelics are capable of doing so to variable degrees. 4-AcO-DMT (O-acetylpsilocin or psilacetin) is a synthetic acetylated analogue of psilocin and is a prodrug of psilocin similarly to psilocybin.

- Mescaline (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine) is a phenethylamine alkaloid found in various species of cacti, the best-known of these being peyote (Lophophora williamsii) and the San Pedro cactus (Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi, syn. Echinopsis pachanoi). Mescaline has effects comparable to those of LSD and psilocybin.[30] Ceremonial San Pedro use seems to be characterized by relatively strong spiritual experiences, and low incidence of challenging experiences.[31]

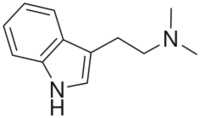

- DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) is an indole alkaloid found in various species of plants. Traditionally, it is consumed by tribes in South America in the form of ayahuasca. A brew is used that consists of DMT-containing plants as well as plants containing MAOIs, specifically harmaline, which allows DMT to be consumed orally without being rendered inactive by monoamine oxidase enzymes in the digestive system.[32] A pharmaceutical version of ayahuasca is called pharmahuasca.[33] In the Western world, DMT is more commonly consumed via the vaporisation of freebase DMT. Whereas ayahuasca typically lasts for several hours, inhalation has an onset measured in seconds and has effects measured in minutes, being much more intense.[34] Particularly in vaporised form, DMT has the ability to cause users to enter a hallucinatory realm fully detached from reality, being typically characterised by hyperbolic geometry, and described as defying visual or verbal description.[35] Users have also reported encountering and communicating with entities within this hallucinatory state.[36] DMT is the archetypal substituted tryptamine, being the structural scaffold of psilocybin and, to a lesser extent, the lysergamides.

- 2C-B (2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromophenethylamine) is a substituted phenethylamine first synthesized in 1974 by Alexander Shulgin.[37] 2C-B is both a psychedelic and a mild entactogen, with its psychedelic effects increasing and its entactogenic effects decreasing with dose.[38][39][40] 2C-B is the most well-known compound in the 2C family, their general structure being discovered as a result of modifying the structure of mescaline.[37]{{page needed|date=January 2023} synthetic phenethylamine psychedelic.

MDMA ("ecstasy") is sometimes said to also have weak psychedelic effects, but it acts and is classified mainly as an entactogen rather than as a hallucinogen.[41] Certain related drugs like MDA and MMDA have greater psychedelic effects however.[37]

Uses

Recreational

Recreational use of psychedelics has been common since the psychedelic era of the mid-1960s and continues to feature at festivals and events such as Burning Man.[18][19] A 2013 survey found that 13.4% of American adults had used a psychedelic at some point in their lives.[43]

A June 2024 report by the RAND Corporation indicated that psilocybin mushrooms are currently the most widely used psychedelic drug among U.S. adults. According to the RAND national survey, 3.1% of adults reported psilocybin use in the past year, while about 12% reported lifetime use. Similar lifetime prevalence was reported for LSD, whereas MDMA (ecstasy) showed lower lifetime use at 7.6%. Fewer than 1% of adults reported using any psychedelic in the past month.[44]

A nationwide survey of 11,299 adults in Germany, published in 2025, found that 5.0% of respondents reported lifetime psychedelic use, with 0.7% reporting use within the past six months.[45] Approximately 3% of respondents had used LSD, LSD analogues, psilocybin, or related substances at least once in their lifetime, and 0.5% had done so within the past six months. Lifetime prevalence of medium-to-high dosing (3.9%) was higher than microdosing (2.7%). Usage patterns varied by sociodemographic characteristics, including sex, age, residence, income, and marital status.

Traditional

A number of frequently mentioned or traditional psychedelics such as Ayahuasca (which contains DMT), San Pedro, Peyote, and Peruvian torch (which all contain mescaline), Psilocybe mushrooms (which contain psilocin/psilocybin) and Tabernanthe iboga (which contains the unique psychedelic ibogaine) all have a long and extensive history of spiritual, shamanic and traditional usage by indigenous peoples in various world regions, particularly in Latin America, but also Gabon, Africa in the case of iboga.[46] Different countries and/or regions have come to be associated with traditional or spiritual use of particular psychedelics, such as the ancient and entheogenic use of psilocybe mushrooms by the native Mazatec people of Oaxaca, Mexico[47] or the use of the ayahuasca brew in the Amazon basin, particularly in Peru for spiritual and physical healing as well as for religious festivals.[48] Peyote has also been used for several thousand years in the Rio Grande Valley in North America by native tribes as an entheogen.[49] In the Andean region of South America, the San Pedro cactus (Trichocereus macrogonus var. pachanoi, syn. Echinopsis pachanoi) has a long history of use, possibly as a traditional medicine. Archaeological studies have found evidence of use going back two thousand years, to Moche culture,[50] Nazca culture,[51] and Chavín culture. Although authorities of the Roman Catholic church attempted to suppress its use after the Spanish conquest,[52] this failed, as shown by the Christian element in the common name "San Pedro cactus" – Saint Peter cactus. The name has its origin in the belief that just as St Peter holds the keys to heaven, the effects of the cactus allow users "to reach heaven while still on earth."[53] In 2022, the Peruvian Ministry of Culture declared the traditional use of San Pedro cactus in northern Peru as cultural heritage.[54]

Although people of Western culture have tended to use psychedelics for either psychotherapeutic or recreational reasons, most indigenous cultures, particularly in South America, have seemingly tended to use psychedelics for more supernatural reasons such as divination. This can often be related to "healing" or health as well but typically in the context of finding out what is wrong with the individual, such as using psychedelic states to "identify" a disease and/or its cause, locate lost objects, and identify a victim or even perpetrator of sorcery.[55] In some cultures and regions, even psychedelics themselves, such as ayahuasca and the psychedelic lichen of eastern Ecuador (Dictyonema huaorani) that supposedly contains both 5-MeO-DMT and psilocybin, have also been used by witches and sorcerers to conduct their malicious magic, similarly to nightshade deliriants like brugmansia and latua.[55]

Medical

Psychedelic therapy (or psychedelic-assisted therapy) is the proposed use of psychedelic drugs to treat mental disorders.[56] As of 2021, psychedelic drugs are controlled substances in most countries and psychedelic therapy is not legally available outside clinical trials, with some exceptions.[57][58]

The procedure for psychedelic therapy differs from that of therapies using conventional psychiatric medications. While conventional medications are usually taken without supervision at least once daily, in contemporary psychedelic therapy the drug is administered in a single session (or sometimes up to three sessions) in a therapeutic context.[59] The therapeutic team prepares the patient for the experience beforehand and helps them integrate insights from the drug experience afterwards.[60][61][62] After ingesting the drug, the patient normally wears eyeshades and listens to music to facilitate focus on the psychedelic experience, with the therapeutic team interrupting only to provide reassurance if adverse effects such as anxiety or disorientation arise.[60][61]

As of 2022, the body of high-quality evidence on psychedelic therapy remains relatively small and more, larger studies are needed to reliably show the effectiveness and safety of psychedelic therapy's various forms and applications.[23][24] On the basis of favorable early results, ongoing research is examining proposed psychedelic therapies for conditions including major depressive disorder,[23][63] and anxiety and depression linked to terminal illness.[23][64] The United States Food and Drug Administration has granted breakthrough therapy status, which expedites the assessment of promising drug therapies for potential approval, to psilocybin therapy for treatment-resistant depression and major depressive disorder.[57]

It has been proposed that psychedelics used for therapeutic purposes may act as active "super placebos".[65][66][67]

Microdosing

Psychedelic microdosing is the practice of using sub-threshold doses (microdoses) of psychedelics in an attempt to improve creativity, boost physical energy level, emotional balance, increase performance on problems-solving tasks and to treat anxiety, depression and addiction.[68][69] The practice of microdosing has become more widespread in the 21st century with more people claiming long-term benefits from the practice.[70][71]

A 2022 study recognized signatures of psilocybin microdosing in natural language and concluded that low amount of psychedelics have potential for application, and ecological observation of microdosing schedules.[72][73]

Dosing

The table below provides doses of major serotonergic psychedelics as well as the entactogen and mild psychedelic MDMA ("ecstasy") that have been determined on the basis of clinical studies.[74][75][76][77][78][79][80] Other dosingschemes have also been reported.[76]

| Psychedelic | LSDa | Psilocybin | Mescalineb | DMT (i.v.)c | MDMAd | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subthreshold or microdoses | <10 μg | <2.5 mg | <75 mg | N/A | N/A | ||

| Low dose/minidose | 20–50 μg | 5–10 mg | 100–200 mg | 0.6 mg/min | 25–50 mg | ||

| Intermediate/good effect dose | 100 μg | 20 mg | 500 mg | 1.2 mg/min | 125–200 mg | ||

| High/ego-dissolution dose | 200 μg | 30–40 mg | 1,000 mg | 1.8 mg/min | N/A | ||

| Notes: (1) All doses are for oral administration unless otherwise indicated. (2) For the psychedelics, doses are considered to be roughly equivalent in terms of peak or overall response. Footnotes: a = As LSD free base (100 μg LSD base = 146 μg LSD tartrate). b = As mescaline hydrochloride. c = As DMT fumarate given as constant infusions for >30 minutes. d = As MDMA hydrochloride. | |||||||

In the case of dried psilocybin-containing mushrooms, microdoses are 0.1 g to 0.3 g and psychedelic doses are 1.0 g to 3.5–5.0 g.[81][82][83] The preceding 1.0 to 5.0 g range corresponds to psilocybin doses of about 10 to 50 mg.[83] Psilocybin-containing mushrooms vary in their psilocybin and psilocin content, but are typically around 1% of the dried weight of the mushrooms (in terms of total or combined psilocybin and psilocin content).[82][84][85][83][86][87][88][89] Psilocybin and psilocin are similar in potency and dose but psilocin is about 1.4-fold more active, this being related to the difference in molecular weight between the two compounds.[85][90][91]

Some psychedelics, such as 2C-B, 2C-E, and 4-HO-DiPT, have been said to have steep dose–response curves, meaning that the difference in dose between a light experience and an overwhelming disconnection from reality can be small.[37]: 506, 518 [92]: 467

Effects

Psychedelic effects

Although several attempts have been made, starting in the 19th and 20th centuries, to define common phenomenological structures of the effects produced by classic psychedelics, a universally accepted taxonomy does not yet exist.[93][94] At lower doses, features of psychedelic experiences include sensory alterations, such as the warping of surfaces, shape suggestibility, pareidolia, and color variations. Users often report intense colors that they have not previously experienced, and repetitive geometric shapes or form constants are common as well. Higher doses often cause intense and fundamental alterations of sensory (notably visual) perception, such as synesthesia or the experience of additional spatial or temporal dimensions.[95] Tryptamines are well documented to cause classic psychedelic states, such as increased empathy, visual distortions (drifting, morphing, breathing, melting of various surfaces and objects), auditory hallucinations, ego dissolution or ego death with high enough dose, mystical, transpersonal and spiritual experiences, autonomous "entity" encounters, time distortion, closed eye hallucinations and complete detachment from reality with a high enough dose.[96] Luis Luna describes psychedelic experiences as having a distinctly gnosis-like quality, and says that they offer "learning experiences that elevate consciousness and can make a profound contribution to personal development."[97] Czech psychiatrist Stanislav Grof studied the effects of psychedelics like LSD early in his career and said of the experience, that it commonly includes "complex revelatory insights into the nature of existence… typically accompanied by a sense of certainty that this knowledge is ultimately more relevant and 'real' than the perceptions and beliefs we share in everyday life." Traditionally, the standard model for the subjective phenomenological effects of psychedelics has typically been based on LSD, with anything that is considered "psychedelic" evidently being compared to it and its specific effects.[5]

Good trips are reportedly deeply pleasurable, and typically involve intense joy or euphoria, a greater appreciation for life, reduced anxiety, a sense of spiritual enlightenment, and a sense of belonging or interconnectedness with the universe.[98][99] Negative experiences, colloquially known as "bad trips," evoke an array of dark emotions, such as irrational fear, anxiety, panic, paranoia, dread, distrustfulness, hopelessness, and even suicidal ideation.[100] While it is impossible to predict when a bad trip will occur, one's mood, surroundings, sleep, hydration, social setting, and other factors can be controlled (colloquially referred to as "set and setting") to minimize the risk of a bad trip.[101][102] The concept of "set and setting" also generally appears to be more applicable to psychedelics than to other types of hallucinogens such as deliriants, hypnotics and dissociative anesthetics.[103]

Psychedelics include naturally occurring tryptamines like psilocybin and DMT, the naturally occurring phenethylamine mescaline, and naturally occurring lysergamides like ergine (lysergic acid amide; LSA), as well as synthetic analogues and derivatives like LSD and 2C-B. Many of these psychedelics cause remarkably similar effects, despite their different chemical structures. However, many users anecdotally report that the three major families have subjectively different qualities in the "feel" of the experience, which are difficult to describe.{{Citation needed|date=April 2025} l differences between the drugs; for instance, 5-MeO-DMT rarely produces the visual effects typical of other psychedelics.[5][104] As additional examples, DiPT is said to primarily affect the auditory sense,[105][37] 2C-T-17[37] and ASR-3001 (5-MeO-iPALT)[106][107][108] are said to produce psychedelic effects on thinking or "head space" with few or no visuals, and N-methyltryptamine (NMT) has been said to be a primarily spatial psychedelic.[109][110]

The visuals of psychedelics have been reproduced in video and image form using artificial intelligence.[111][112][113][114][115]

Some rare individuals do not experience hallucinogenic effects with serotonergic psychedelics.[116]

Other psychoactive effects

Some psychedelics have been associated with other psychoactive effects in addition to their hallucinogenic effects.[117][118][37] For example, psychedelics like LSD and DOM have been described as having mild stimulant and/or "psychic-energizing" (i.e., acute antidepressant) effects.[117][118] Some psychedelics and related drugs, like DOET (low doses), Ariadne, and ASR-2001 (2CB-5PrO), have been investigated specifically for such effects.[118][37][119][120][107] 2C-B has been said to have mild entactogenic effects at low doses.[38][39][40]

Some drugs, such as MDxx compounds like MDMA and MDA as well as α-alkyltryptamines like α-methyltryptamine (AMT), are entactogens and/or stimulants acting at monoamine transporters in addition to having varying degrees of psychedelic effects.[121][41][37]

Psychedelic afterglows

Psychedelics are associated with an afterglow, also known as positive subacute or post-experience effects, which may last days or even weeks after the psychedelic experience.[122][123][124][125] These effects include reduction in psychopathology and increased well-being, mood, mindfulness, social functioning, spirituality, and executive functioning, and positive behavioral changes.[122] They also include mixed changes in personality, values, attitudes, creativity, and flexibility, as well as adverse effects like headaches, sleep disturbances, and sometimes increased psychological distress.[122] The afterglow period has been associated with changes in brain function, neuroplasticity, and immune system function.[124][126][127][128] Both psychological and pharmacological effects may be involved in the afterglow phenomenon.[123]

In 1898, the English writer and intellectual Havelock Ellis reported a heightened perceptual sensitivity to "the more delicate phenomena of light and shade and color" for a prolonged period of time after his exposure to mescaline.[129] The term "psychedelic afterglow" was first formally coined in the 1960s.[122] Albert Hofmann, the discoverer of LSD, said the following about the aftermath of his first full LSD experience in his 1980 book LSD: My Problem Child:[130]

Exhausted, I then slept, to awake next morning refreshed, with a clear head, though still somewhat tired physically. A sensation of well-being and renewed life flowed through me. Breakfast tasted delicious and gave me extraordinary pleasure. When I later walked out into the garden, in which the sun shone now after a spring rain, everything glistened and sparkled in a fresh light. The world was as if newly created. All my senses vibrated in a condition of highest sensitivity, which persisted for the entire day.

During a speech on his 100th birthday in 2006, Hofmann additionally said of LSD:[131]

It gave me an inner joy, an open mindedness, a gratefulness, open eyes and an internal sensitivity for the miracles of creation... I think that in human evolution it has never been as necessary to have this substance LSD. It is just a tool to turn us into what we are supposed to be.

Adverse effects

Psychedelic drugs are addictive psychologically, with little to no physical addiction in classical psychedelics.[20][21][5]

Risks do exist during an unsupervised psychedelic experience, however; Ira Byock wrote in 2018 in the Journal of Palliative Medicine that psilocybin is safe when administered to a properly screened patient and supervised by a qualified professional with appropriate set and setting. However, he called for an "abundance of caution" because in the absence of these conditions a range of negative reactions is possible, including "fear, a prolonged sense of dread, or full panic." He notes that driving or even walking in public can be dangerous during a psychedelic experience because of impaired hand-eye coordination and fine motor control.[132] In some cases, individuals taking psychedelics have performed dangerous or fatal acts because they believed they possessed superhuman powers.[5]

Psilocybin-induced states of mind share features with states experienced in psychosis, and while a causal relationship between psilocybin and the onset of psychosis has not been established as of 2011, researchers have called for investigation of the relationship.[133] Many of the persistent negative perceptions of psychological risks are unsupported by the currently available scientific evidence, with the majority of reported adverse effects not being observed in a regulated and/or medical context.[134] A population study on associations between psychedelic use and mental illness published in 2013 found no evidence that psychedelic use was associated with increased prevalence of any mental illness.[135] In any case, induction of psychosis has been associated with psychedelics in small percentages of individuals, and the rates appear to be higher in people with schizophrenia.[136]

Using psychedelics poses certain risks of re-experiencing of the drug's effects, including flashbacks and hallucinogen persisting perception disorder (HPPD).[133] These non-psychotic effects are poorly studied, but the permanent symptoms (also called "endless trip") are considered to be rare.[137]

Serotonergic psychedelics are agonists not only of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor but also of the serotonin 5-HT2B receptor and other serotonin receptors.[138][139] A potential risk of frequent repeated use of serotonergic psychedelics is cardiac fibrosis and valvulopathy caused by serotonin 5-HT2B receptor activation.[138][139] However, single high doses or widely spaced doses (e.g., months) are widely thought to be safe and concerns about cardiac toxicity apply more to chronic psychedelic microdosing or very frequent use (e.g., weekly).[138][139] Selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists that do not activate the serotonin 5-HT2B receptor or other serotonin receptors, such as 25CN-NBOH, DMBMPP, and LPH-5, have been developed and are being studied.[140][141][142] Selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists are expected to avoid the cardiac risks of serotonin 5-HT2B receptor activation.[142]

Overdose

There have been a handful of cases of fatal overdose with LSD, psilocybin, and mescaline.[143][144] There have also been cases of death with dimethyltryptamine (DMT), 5-MeO-DMT, 2C-B, Bromo-DragonFLY, NBOMes like 25I-NBOMe, and other psychedelics.[143][145] LSD and psilocybin appear to have very wide margins of safety with overdose, whereas mescaline and 2C-B have much narrower margins, and NBOMes appear to be especially toxic and uniquely linked to serotonin syndrome-type symptoms.[143] Major psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin do not cause serotonin syndrome, which is thought to be due to the fact that they act as partial agonists of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[146][143][147] Conversely, psychedelics like NBOMes have higher activational efficacy at this receptor.[146][147] In terms of extrapolated human lethal doses based on animal studies and human case reports, lethal doses of psychedelics relative to typical recreational doses are estimated to be 1,000-fold for LSD, 200-fold for psilocybin, 50-fold for oral DMT (as ayahuasca), and 24-fold for mescaline.[143] Estimates for other psychedelics, like 5-MeO-DMT and 2C-B, could not be made.[143]

Interactions

Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists can block the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics.[148] Numerous drugs act as serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, for instance antidepressants like trazodone and mirtazapine, antipsychotics like quetiapine, olanzapine, and risperidone, and other agents like ketanserin, pimavanserin, cyproheptadine, and pizotifen.[148][149] Such drugs are sometimes referred to as "trip killers" due to their ability to prevent or abort the hallucinogenic effects of psychedelics.[150][149][151] Besides serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, non-hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor partial agonists, such as lisuride, may also block the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics.[152][153]

The serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist buspirone has been found to markedly reduce the hallucinogenic effects of psilocybin in humans.[148][154][155] Conversely, the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor antagonist pindolol has been found to potentiate the hallucinogenic effects of DMT by 2- to 3-fold in humans.[155][156] Serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonism may modify and self-inhibit the effects of psychedelics that possess this property.[104][157][154][158][159][160] A particularly notable example is 5-methoxytryptamine derivatives such as 5-MeO-DMT, which are more potent serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonists than other psychedelics and have qualitatively unique and differing hallucinogenic effects.[104][160][161]

Benzodiazepines, for example diazepam, alprazolam, clonazepam, and lorazepam, as well as alcohol, which act as GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators, have been limitedly studied in combination with psychedelics and are not currently known to directly interact with them.[162][148] However, these GABAergic drugs produce effects such as anxiolysis, sedation, and amnesia, and in relation to this, may diminish or otherwise oppose the effects of psychedelics.[148][150][149][151][163] As a result of this, benzodiazepines and alcohol are often used by recreational users as "trip killers" to manage difficult hallucinogenic experiences with psychedelics, for instance experiences with prominent anxiety.[150][149][151] The safety of this strategy is not entirely clear and might have risks.[150][162][149][151] However, benzodiazepines have been used clinically to manage the adverse psychological effects of psychedelics, for instance in clinical studies and in the emergency department.[162][164][165][166][167] A clinical trial of psilocybin and midazolam coadministration found that midazolam clouded the effects of psilocybin and impaired memory of the experience.[168][169] Benzodiazepines might interfere with the therapeutic effects of psychedelics, such as sustained antidepressant effects.[170][171]

Some serotonergic psychedelics, for instance dimethyltryptamine (DMT) and 5-MeO-DMT, are highly susceptible substrates for monoamine oxidase (MAO), specifically MAO-A, and hence can be greatly potentiated by monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).[148][172][173] An example of this is ayahuasca, in which plants containing both DMT and harmala alkaloids acting as MAOIs such as harmine and harmaline are combined.[172] This allows DMT to become orally active and to have a much longer duration of action than usual.[172] The 2C psychedelics, such as 2C-B, 2C-I, and 2C-E, are also substrates of both MAO-A and MAO-B, and may likewise be greatly potentiated by MAOIs.[174][175] Examples of MAOIs that may potentiate psychedelics behaving as MAO-A and/or MAO-B substrates include phenelzine, tranylcypromine, isocarboxazid, moclobemide, and selegiline.[148] Combination of MAO-substrate psychedelics with MAOIs can result in overdose and serious toxicity, including death.[148][174] Other psychedelics, such as LSD, are not substrates of MAO and are not potentiated by MAOIs.[148] The extent to which psilocin (and by extension psilocybin) is metabolized by MAO, specifically MAO-A, is not fully clear, but has ranged from 4% to 33% in different studies based on metabolite excretion.[176][79][85] However, circulating levels of the deaminated metabolite of psilocin are far higher than those of free unmetabolized psilocin with psilocybin administration.[177][178] An early clinical study of psilocybin in combination with short-term tranylcypromine pretreatment found that tranylcypromine marginally potentiated the peripheral effects of psilocybin, including pressor effects and mydriasis, but overall did not significantly modify the psychoactive and hallucinogenic effects of the psilocybin, although some of its emotional effects were said to be reduced and some of its perceptual effects were said to be amplified.[179][180][181]

Some psychedelics are substrates of cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzymes, for instance LSD being a substrate of CYP2D6 as well as of several other CYP450 enzymes.[148][182] As such, CYP450 inhibitors may increase exposure to CYP450-substrate psychedelics such as LSD and thereby potentiate their effects as well as risks.[148][182] A clinical study found that administration of LSD to people taking paroxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and strong CYP2D6 inhibitor, increased LSD exposure by about 1.5-fold.[182] The combination was well-tolerated and did not modify the pleasant subjective effects or physiological effects of LSD, whereas negative effects of LSD, including "bad drug effect", anxiety, and nausea, were reduced.[182] Similarly to the findings with a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor, a pharmacogenomic clinical study with LSD found that LSD levels were 75% higher in people with non-functional CYP2D6 (poor metabolizers) compared to those with functional CYP2D6.[148][183]

Serotonin syndrome can be caused by combining psychedelics with other serotonergic drugs, including certain antidepressants, opioids, psychostimulants (e.g. MDMA), serotonin 5-HT1 receptor agonists (e.g. triptans), herbs or supplements, and others.[184][185][186][187]

A high rate of seizures has been reported when people on lithium have taken serotonergic psychedelics.[179][188][189] In an analysis of online reports, 47% of 62 accounts reported seizures when a psychedelic was taken while on lithium.[179][188][189] The mechanism of this interaction is unclear.[179][189]

Pharmacology

Mechanism of action

Most serotonergic psychedelics act as non-selective agonists of serotonin receptors, including of the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors, but often also of other serotonin receptors, such as the serotonin 5-HT1 receptors.[74][190] They are thought to mediate their hallucinogenic effects specifically by activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.[191][11] Psychedelics (including tryptamines like psilocin, DMT, and 5-MeO-DMT; phenethylamines like mescaline, DOM, and 2C-B; and ergolines and lysergamides like LSD) all act as agonists of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.[157][191][141] Some psychedelics, such as phenethylamines like DOM and 2C-B, show high selectivity for the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors over other serotonin receptors.[191][141] There is a very strong correlation between 5-HT2A receptor affinity and human hallucinogenic potency.[191] In addition, the intensity of hallucinogenic effects in humans is directly correlated with the level of serotonin 5-HT2A receptor occupancy as measured with positron emission tomography (PET) imaging.[191][11] Serotonin 5-HT2A receptor blockade with drugs like the semi-selective ketanserin and the non-selective risperidone can abolish the hallucinogenic effects of psychedelics in humans.[191][11] However, studies with more selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, like pimavanserin, are still needed.[192]

In animals, potency for stimulus generalization to the psychedelic DOM in drug discrimination tests is strongly correlated with serotonin 5-HT2A receptor affinity.[191][11] Non-selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, like ketanserin and pirenperone, and selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, like volinanserin (MDL-100907), abolish the stimulus generalization of psychedelics in drug discrimination tests.[191] Conversely, serotonin 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptor antagonists are ineffective.[191] The potencies of serotonin 5-HT2 receptor antagonists in blocking psychedelic substitution are strongly correlated with their serotonin 5-HT2A receptor affinities.[191] Highly selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists have recently been developed and show stimulus generalization to psychedelics, whereas selective serotonin 5-HT2C receptor agonists do not do so.[191] The head-twitch response (HTR) is induced by serotonergic psychedelics and is a behavioral proxy of psychedelic-like effects in animals.[191][193] The HTR is invariably induced by serotonergic psychedelics, is blocked by selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonists, and is abolished in serotonin 5-HT2A receptor knockout mice.[191][11] In addition, there is a strong correlation between hallucinogenic potency in humans and potency in the HTR assay.[11][194] Moreover, the HTR paradigm is one of the only animal tests that can distinguish between hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists and non-hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists, such as lisuride.[191] In accordance with the preceding animal and human findings, it has been said that the evidence that the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor mediates the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics is overwhelming.[11]

The serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activates several downstream signaling pathways.[11][195][196] These include the Gq, β-arrestin2, and other pathways.[11][196] Activation of both the Gq and β-arrestin2 pathways have been implicated in mediating the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics.[11][195][197] However, subsequently, activation of the Gq pathway and not β-arrestin2 has been implicated.[196][195][197][126][198] Interestingly, Gq signaling appeared to mediate hallucinogenic-like effects, whereas β-arrestin2 mediated receptor downregulation and tachyphylaxis.[196][198] The lack of psychedelic effects with non-hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists may be due to partial agonism of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor with efficacy insufficient to produce psychedelic effects or may be due to biased agonism of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor.[191] There appears to be a threshold level of Gq activation (in terms of intrinsic activity, with Emax >70%) required for production of hallucinogenic effects.[141][197][198] Full agonists and partial agonists above this threshold are psychedelic 5-HT2A receptor agonists, whereas partial agonists below this threshold, such as lisuride, 2-bromo-LSD, 6-fluoro-DET, 6-MeO-DMT, and Ariadne, are non-hallucinogenic 5-HT2A receptor agonists.[141][198][153][152][120] In addition, biased agonists that activate β-arrestin2 signaling but not Gq signaling, such as ITI-1549, IHCH-7086, and 25N-N1-Nap, are non-hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists.[141][198][199]

The hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics may be critically mediated by serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activation in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).[191] Layer V pyramidal neurons in this area are especially discussed.[191][200] Activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in the mPFC results in marked excitatory and inhibitory effects as well as increased release of glutamate and GABA.[191] Direct injection of serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists into the mPFC produces the HTR.[191] Drugs that suppress glutamatergic activity in the mPFC, including AMPA receptor antagonists, metabotropic glutamate mGlu2/3 receptor agonists, μ-opioid receptor agonists, and adenosine A1 receptor agonists, block or suppress many of the neurochemical and behavioral effects of serotonergic psychedelics, including the HTR.[191][201] Metabotropic glutamate mGlu2 receptors are primarily expressed as presynaptic autoreceptors and have inhibitory effects on glutamate release.[191][202] Serotonergic psychedelics have been found to produce frontal cortex hyperactivity in humans in PET and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) imaging studies.[191] The PFC projects to many other cortical and subcortical brain areas, such as the locus coeruleus, nucleus accumbens, and amygdala, among others, and activation of the PFC by serotonergic psychedelics may thereby indirectly modulate these areas.[191] In addition to the PFC, there is moderate to high expression of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in the primary visual cortex (V1), as well as expression of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in other visual areas, and activation of these receptors may contribute to or mediate the visual effects of serotonergic psychedelics.[191][11][203][204][205] Serotonergic psychedelics also directly or indirectly modulate a variety of other brain areas, like the claustrum, and this may be involved in their effects as well.[11][206][207]

Serotonin, as well as drugs that increase serotonin levels, like the serotonin precursor 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and serotonin releasing agents, are non-hallucinogenic in humans despite increasing activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors.[202][208][209][210] Serotonin is a hydrophilic molecule which cannot easily cross biological membranes without active transport, and the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor is usually expressed as a cell surface receptor that is readily accessible to extracellular serotonin.[208][210] The HTR, a behavioral proxy of psychedelic-like effects, appears to be mediated by activation of intracellularly expressed serotonin 5-HT2A receptors in a population of mPFC neurons that do not also express the serotonin transporter (SERT) and hence cannot be activated by serotonin.[208][210] In contrast to serotonin, serotonergic psychedelics are more lipophilic than serotonin and are able to readily enter these neurons and activate the serotonin 5-HT2A receptors within them.[208][210] Artificial expression of the SERT in this population of neurons in animals resulted in a serotonin releasing agent that doesn't normally produce the HTR being able to do so.[210] Although serotonin itself is non-hallucinogenic, at very high concentrations achieved pharmacologically (e.g., injected into the brain or with massive doses of 5-HTP) it can produce psychedelic-like effects in animals by being metabolized by indolethylamine N-methyltransferase (INMT) into more lipophilic N-methylated tryptamines like N-methylserotonin and bufotenin (N,N-dimethylserotonin).[211][193][202][212][208][210]

In addition to their hallucinogenic effects, serotonergic psychedelics may also produce a variety of other effects, including psychoplastogenic (i.e., neuroplasticity-enhancing),[213][214][215][216] antidepressant,[141][217][126] anxiolytic,[218][219] empathy-enhancing or prosocial effects,[220][221][222] anti-obsessional,[223][224][225][226][227] anti-addictive,[228][229][230][231] anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects,[232][233][234][235][236] analgesic effects,[237][238][239] and/or antimigraine effects.[240][241][242] While psychedelics themselves are also being clinically evaluated for these potential therapeutic benefits, non-hallucinogenic serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists, which are often analogues of serotonergic psychedelics, have been developed and are being studied for potential use in medicine in an attempt to provide some such benefits without hallucinogenic effects.[141][243][244]

Although the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics are thought to be mediated by serotonin 5-HT2A receptor activation, interactions with other receptors, such as the serotonin 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2B, and 5-HT2C receptors among many others, may additionally contribute to and modulate their effects.[191][245] Certain psychedelics, including LSD and psilocin, have been reported to act as highly potent positive allosteric modulators of the tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB), one of the signaling receptors of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF).[216][246][245][247] However, subsequent studies failed to reproduce these findings and instead found no interaction of LSD or psilocin with TrkB.[248] Moreover, the psychoplastogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics, including dendritogenesis, spinogenesis, and synaptogenesis, appear to be mediated by activation of serotonin 5-HT2A receptors, whereas psychedelics do not generally stimulate neurogenesis.[216][215][245]

The factors responsible for differences in psychoactive and hallucinogenic effects between different psychedelics are incompletely understood but may include (1) differences in selectivity for the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor or off-target activity; (2) differences in functional selectivity for different serotonin 5-HT2A receptor downstream signaling pathways; and (3) differences in patterns or balances of distribution to different brain areas.[13][4][104][249]

Chemistry

The three major chemical groups of serotonergic psychedelics include the tryptamines, phenethylamines, and lysergamides, which each have different profiles of pharmacological activity.[13][197]

Tryptamines

Tryptamines are derivatives of tryptamine and are structurally related to the monoamine neurotransmitter serotonin (also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT). Many tryptamines act as non-selective serotonin receptor agonists, including of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor. Some tryptamines also act as monoamine releasing agents, including of serotonin, norepinephrine, and/or dopamine. Examples of psychedelic tryptamines include psilocin and psilocybin, dimethyltryptamine (DMT), 5-MeO-DMT, bufotenin, α-methyltryptamine (αMT), 4-AcO-DMT (psilacetin), 4-HO-MET, 5-MeO-MiPT, and 5-MeO-DiPT, among others.[13][250] Harmala alkaloids like harmaline and iboga-type alkaloids like ibogaine are cyclized tryptamines and may also be considered hallucinogenic tryptamines.[251][252]

Phenethylamines

Phenethylamines, as well as amphetamines (α-methylphenethylamines), are derivatives of β-phenethylamine and are structurally related to the monoamine neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. Some phenethylamines and amphetamines, particularly those with methoxy and other substitions on the phenyl ring, are potent serotonin 5-HT2 receptor agonists, including of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor, and can produce psychedelic effects. In contrast to phenethylamines and amphetamines generally, most psychedelic phenethylamines are not monoamine releasing agents.[253][254] Examples of psychedelic phenethylamines and amphetamines include mescaline and other scalines like trimethoxyamphetamine (TMA) and escaline, the 2C drugs like 2C-B, 2C-E, and 2C-I, the DOx drugs like DOB, DOI, and DOM, certain MDxx drugs like MDA and MDMA (weak psychedelics), and the NBOMe (25x-NBx) drugs like 25I-NBOMe, among others.[13]

Lysergamides

Lysergamides are ergoline derivatives related to the ergot alkaloids. They are notable in containing both tryptamine and phenethylamine within their chemical structures. As such, ergolines and lysergamides may be considered structurally related to the monoamine neurotransmitters. Many ergolines and lysergamides act as highly promiscuous ligands of monoamine receptors, including of serotonin, dopamine, and adrenergic receptors. Some lysergamides are efficacious serotonin 5-HT2A receptor agonists and thereby produce psychedelic effects. Examples of psychedelic lysergamides include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), ergine (lysergic acid amide; LSA), isoergine (isolysergic acid amide; iso-LSA), ETH-LAD, AL-LAD, 1P-LSD, 1S-LSD, ALD-52 (1A-LSD), LA-SS-Az (LSZ), ergonovine (ergometrine; lysergic acid propanolamide), methylergometrine (methylergonovine), and methysergide (methylmethylergonovine), among others.[13] Ergine, isoergine, and ergonovine occur naturally in morning glories and certain fungi like ergot and Periglandula species, while others like LSD are synthetic. LSD is among the most potent psychedelics, as well as psychoactive drugs in general, that are known.[13]

Others

Other psychedelics not belonging to any of the above three structural families have been discovered, for instance certain arylpiperazine derivatives like quipazine,[255][256] the antiretroviral drug efavirenz,[257][258][259][260][261] and simplified or partial lysergamides (which are also conformationally constrained tryptamines and/or phenethylamines) like NDTDI and DEMPDHPCA.[262][263][264]

History

Early history

Psychedelics occurring in plants, fungi, and animals have been used by indigenous peoples throughout the world for thousands of years.[265][266][267][268] These psychedelics and their sources include psilocybin and psilocin in psilocybin-containing mushrooms (teonanacatl), dimethyltryptamine (DMT) in ayahuasca (a combination typically of Psychotria viridis and Banisteriopsis caapi), bufotenin in Anadenanthera trees, 5-MeO-DMT in the Colorado River Toad, mescaline in peyote (peyotl) and San Pedro cacti, and ergine and isoergine in morning glories (ololiuqui, tlitliltzin) and ergot, among others.[265][266][267][268] The kykeon of the Eleusinian Mysteries in Ancient Greece might have been a psychedelic, for instance ergot or psilocybin-containing mushrooms.[269][270][268] The earliest archeological evidence of the use of psychedelic plants and fungi by humans dates back roughly 10,000 years.[265][268]

Western characterization

Psychedelics were discovered by the Western world and the scientific community relatively late.[266] The use of hallucinogenic snuffs by indigenous South American people was first observed by Western explorers like Christopher Columbus as early as 1496.[271][249][272] The first written description of an observed psychedelic experience, with cohoba, was published by Ramon Pane in 1511.[273] Spanish explorers observed the use of psilocybin-containing mushrooms (teonanacatl) in Mexico as early as 1519 with the arrival of Hernán Cortés.[86][274] Spanish ethnographer Bernardino de Sahagún traveled to Mexico in 1529 and described the use of these mushrooms in his books.[86] The botanists Richard Spruce and Alfred Russel Wallace observed and described the use of ayahuasca in the Amazon in the 1850s.[266][274]

The phenethylamine psychedelic mescaline

Mescaline is sometimes described as the "first psychedelic", as it was the first to be discovered and characterized by the Western world.[275] American physician John Raleigh Briggs, living in Texas, learned of peyote from Native Americans and Mexicans, who told him that it produced "beautiful visions" and made them journey into the "spirit world".[276][275][277] He obtained mescal buttons from Mexico and published a journal article about trying a very low dose of them in May 1887.[276][275][277] This article is said to have brought peyote into North American pharmacology.[276][277] Briggs described the physiological effects of his experience, such as increased heart rate, and of experiencing "intoxication".[276][277] The article was read by George Davis, of Parke, Davis and Company, who then obtained the buttons from Briggs in June 1887.[276][275] Parke-Davis attempted to market peyote as a cardiac stimulant and for other uses, but met with little success.[276][275] The German pharmacologist Louis Lewin obtained mescal buttons from Parke-Davis during a trip to the United States in 1887 and began studying them and sharing his findings.[275][266]

The first known published description of a hallucinogenic peyote experience was by American neurologist Silas Weir Mitchell in December 1896.[266][278] After reading Mitchell's article, others, including psychologist and sexologist Havelock Ellis, American psychologist William James, and German pharmacologist, chemist, and Lewin rival Arthur Heffter, among others, tried peyote and described their experiences.[275][279][266][274][280] Heffter isolated and ingested mescaline from peyote, experiencing psychedelic effects with the pure compound, in 1897, and published his findings in 1898.[281][276][266][274][282]

Austrian chemist Ernst Späth synthesized mescaline for the first time in 1919.[275] The German pharmaceutical company Merck then began distributing pharmaceutical mescaline in 1920.[275] The German psychiatrist Kurt Beringer, a student of Lewin and an acquaintance of Hermann Hesse and Carl Jung, became the father of psychedelic psychiatry and conducted experiments with mescaline in more than 60 people starting in 1921.[275][266] He published his monograph on the subject, Der Meskalinrausch (Mescaline Intoxication), in 1927.[275][266][283] German–American psychologist Heinrich Klüver published his monograph, Mescal: The Divine Plant and Its Psychological Effects, in English in 1928.[275][266][284] He is said to have been the first to attempt to provide a phenomenological description of the psychedelic experience.[266]

Tryptamine and lysergamide psychedelics

Austrian anthropologist and ethnobotanist Blas Pablo Reko, traveling through Central and South America, wrote of the use of teonanacatl by native Mexican people in Oaxaca in 1919.[266] Reko subsequently sent samples of teonanacatl (Psilocybe mexicana) as well as Ipomoea violacea (morning glory) seeds to Swedish anthropologist Henry Wassén in 1937.[266] Reko had obtained the mushroom sample from Austrian engineer Robert Weitlaner who was working in Mexico.[266] Eventually, Wassén forwarded Reko and Weitlaner's mushroom sample to Harvard University, where the mushrooms came to the attention of American ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes.[266][86] However, they had decomposed so badly that they could not be identified.[266][86] Prior to Wassén obtaining specimens around 1936, the existence of teonanacatl was very controversial and was debated and even denied by some.[86] In 1938, a small group of Westerners, which included Weitlaner's daughter and American anthropologist Jean Basset Johnson, attended a mushroom ceremony.[266][86] They were the first Westerners known to do so and described the event.[266][86] Schultes published reviews of teonanacatl being a hallucinogenic mushroom in the late 1930s.[266][285] Schultes obtained specimens of three of the hallucinogenic mushrooms used in ceremonies, including Psilocybe caerulescens, Panaeolus campanulatus, and Stropharia cubensis, but further investigations of the mushrooms were interrupted by World War II.[86]

Ergine (lysergic acid amide; LSA) and isoergine (isolysergic acid amide; iso-LSA) were first identified from hydrolysis of ergot alkaloids in 1932 and 1936, respectively.[249][286][287] In 1938, Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann, working at Sandoz Laboratories, synthesized lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), a synthetic derivative of ergine, while developing new oxytocic drugs derived from ergot.[266] LSD was not further investigated and was placed in storage for 5 years.[266] In 1943 however, Hofmann worked with LSD again and accidentally discovered its hallucinogenic effects when minute amounts of the potent psychedelic absorbed through his skin.[266][265] His subsequent self-experiment with LSD three days later on April 19 is the psychedelic holiday Bicycle Day.[288] Hofmann and his colleague, psychiatrist Werner Stoll, first described LSD in 1943 and first described its psychedelic effects in 1947.[266][289][290][291][292] LSD began being distributed by Sandoz Laboratories for research purposes under the brand name Delysid in 1949.[293][294]

Schultes described the indigenous and shamanic use of dimethyltryptamine (DMT)-containing psychedelic plants in 1954 and also described the use of hallucinogenic morning glories in the 1950s.[266] The psychedelic effects of synthesized DMT were described by Hungarian chemist and psychiatrist Stephen Szára in 1956.[274][295][266][296][297] Osmond described the hallucinogenic and other effects of morning glory seeds in clinical studies in 1955.[249] Hofmann identified and described ergine and isoergine as the active constituents of morning glory seeds in 1960.[265][298][299][300] Their hallucinogenic effects were first described by Hofmann in 1963.[249][299]

In 1952, couple and amateur ethnomycologists R. Gordon Wasson and Valentina Wasson learned of the ritual use of hallucinogenic mushrooms in the 16th century in Mexico from the published work of Schultes.[86][301] They made several trips to Mexico in search of the mushrooms.[86][301] In mid-1955, the Wassons participated in a mushroom ceremony with Mazatec curandera Maria Sabina in Huautla de Jiménez, Oaxaca, Mexico.[86][301] Gordon Wasson published his experience in an article for Life magazine titled "Seeking the Magic Mushroom" in 1957, while Valentina Wasson published her experience as "I Ate the Sacred Mushroom" in This Week magazine the same year.[86][301] Later in 1957, a second expedition was made by the Wassons to Mexico with French mycologist Roger Heim.[86] Heim identified several of the mushrooms as belonging to the genus Psilocybe.[86] They collected samples of the mushrooms and Heim sent a sample to Hofmann.[86] Hofmann identified psilocybin as the active constituent in 1958 and developed a chemical synthesis for it.[86][274][266] Sandoz Pharmaceuticals began distributing tablets of psilocybin under the brand name Indocybin in 1960.[86]

French scientists Césaire Phisalix and Gabriel Bertrand isolated bufotenin from Bufo toads in 1893 and named it.[302][303][304] The compound was first isolated to purity by Austrian chemist Hans Handovsky in 1920.[302] Clinical studies assessed the effects of bufotenin and were published starting in 1956.[302][305][173] However, the findings of these studies were conflicting, and bufotenin developed a long-standing reputation of being inactive and toxic.[302][305][173] American ethnobotanist Jonathan Ott and colleagues subsequently showed in 2001 that bufotenin is in fact a psychedelic and does not necessarily produce major adverse effects, although marked nausea and vomiting are prominent.[173][306][307] The related psychedelic 5-MeO-DMT was first synthesized by Japanese chemists Toshio Hoshino and Kenya Shimodaira in 1935.[308][309] It was later isolated from Dictyoloma incanescens in 1959.[309] Subsequently, 5-MeO-DMT was isolated from numerous other plants and fungi.[309][308] The compound was isolated from the skin of toads, specifically the Colorado River toad (Incilius alvarius, formerly Bufo alvarius), by Italian chemist and pharmacologist Vittorio Erspamer in 1967.[308][309][310] A 1984 pamphlet by Albert Most (real name Ken Nelson), titled Bufo Alvarius: the Psychedelic Toad of the Sonoran Desert, described how to obtain and use Colorado River toad secretions as a psychedelic drug, and this started its recreational use.[311][312][309]

Mid-20th-century research, popularization, and prohibition

Extensive clinical research on almost exclusively LSD, mescaline, and psilocybin was conducted in the 1950s and 1960s.[274] However, the amount of research done on psilocybin was nowhere near that of LSD.[274] Psychedelics like LSD started to become more visible in the mainstream sphere in the 1950s.[274] English writer Aldous Huxley tried mescaline, which he had obtained from English psychiatrist Humphry Osmond, in 1953, and described its effects in his 1954 book The Doors of Perception.[274][313][314] British politician Christopher Mayhew tried mescaline in 1955 and this was reported on in the media.[265] Osmond, in correspondence with Huxley, coined the term "psychedelic", meaning "mind-manifesting", in 1956.[315][314]

Psychedelics became widely recreationally used by the public, for instance by the hippies, during the counterculture of the 1960s.[266] Harvard psychologists Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert began studying LSD and psilocybin in the early 1960s and ended up being fired from the university in 1963.[274] Sandoz Laboratories ceased distribution of Delysid in 1965.[274] Psychedelics became controlled substances in the United States and internationally in the 1960s and 1970s.[274][265] By the end of the 1960s, psychedelic clinical research throughout the world had largely ceased.[266]

Besides public research, it was eventually learned that the United States government had also conducted research into psychedelics, as possible mind-control and truth-serum drugs, in the 1940s through the 1970s, for instance Project MKUltra by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the Edgewood Arsenal research by the U.S. Army.[316][317]

Creation of other synthetic psychedelics

The psychedelic effects of 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA), a synthetic analogue of mescaline that had been derived from amphetamine in 1910, were discovered by American chemist and pharmacologist Gordon Alles in 1930, but weren't subsequently described by him until 1959.[318][319][320][321] 3,4,5-Trimethoxyamphetamine (TMA), another synthetic mescaline analogue, was first described in 1947 and its psychedelic effects were described in 1955.[322][323][324][325] 2,4,5-Trimethoxyphenethylamine (2C-O), a synthetic positional isomer of mescaline, was synthesized and claimed to be psychedelic similarly to mescaline in 1931, but later trials found it to be inactive.[325][326] Various synthetic tryptamine psychedelics, such as diethyltryptamine (DET), 4-PO-DET (CEY-19), and 4-HO-DET (CZ-74), were developed in the late 1950s.[327][328][329] In addition, the synthetic α-alkyltryptamine analogues α-methyltryptamine (AMT; Indopan) and α-ethyltryptamine (AET; Monase), which are psychedelics and/or entactogens, were marketed and clinically used at non-hallucinogenic doses as antidepressants in the early 1960s, but were quickly withdrawn due to physical toxicity.[330][331][121] Numerous synthetic psychedelic tryptamines were known by the mid-1970s.[249]

Alexander Shulgin, an American chemist working at Dow Chemical Company, tried mescaline by 1960.[118][332] This experience has been described as "the most consequential mescaline trip of the sixties", as it caused Shulgin to redirect his focus and life's work to psychedelic chemistry.[118][332] Starting in the 1960s, Shulgin synthesized and gradually described hundreds of novel synthetic psychedelics as well as entactogens in scientific publications and published books such as PiHKAL (1991) and TiHKAL (1997).[274][265][118] Notable major examples of these drugs have included the DOx psychedelic DOM, the 2C psychedelic 2C-B, and the MDxx entactogen MDMA, among others.[265][41][319] However, MDMA was not an original creation of Shulgin's but had previously been first synthesized in 1912 and had surfaced as a recreational drug related to MDA by the mid- to late-1960s.[333][334][319] Instead, Shulgin had merely served to help popularize and spread awareness about MDMA and its unique effects.[333][334][319]

MDMA became outlawed in the mid-1980s.[265][335] In response to this, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) was founded by Rick Doblin in 1986 and began efforts to develop MDMA and other psychedelics as medicines.[335] American chemist David E. Nichols has developed numerous novel psychedelics and entactogens from the 1970s to present.[336][337][338] Swiss chemist Daniel Trachsel, sometimes referred to as the "German Shulgin", has also developed and published numerous novel psychedelics as well as entactogens since the 1990s.[339][340]

NBOMe psychedelics such as 25I-NBOMe, derived from structural modification of 2C psychedelics, were first described by Ralf Heim and colleagues by 2000.[341][342][343] The NBOMe drugs were subsequently encountered as novel recreational drugs by 2010, and by 2012 had eclipsed other psychedelics like LSD and psilocybin-containing mushrooms in popularity, at least for a time.[344][345][346]

Psychedelics, serotonin, and their actions

Serotonin, also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and originally called enteramine, was discovered by Vittorio Erspamer in the 1930s[347] and its structural identity was fully characterized in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[347][348][349] Serotonin was discovered in the brain by Betty Twarog and Irvine Page in 1953.[347][348][350] It was quickly noticed that LSD contains the serotonin-like tryptamine scaffold within its chemical structure.[347][348] Shortly thereafter, it was found that LSD showed serotonin-like effects and could antagonize serotonin in certain assays.[347][348] Studies in the 1960s and 1970s showed that various serotonin antagonists could block the behavioral effects of psychedelics in animals.[351][4][352][353][354] The serotonin receptors, including the serotonin 5-HT2 receptors, were elucidated by the late 1970s.[347][348][355] Mediation of the hallucinogenic effects of psychedelics by serotonin 5-HT2 receptor agonism was proposed by Richard Glennon and other researchers by the early 1980s.[351][191][4][356][357] The human serotonin 5-HT2A receptor was first cloned in 1990.[347][358] The hallucinogenic effects of psilocybin in humans were shown to be blocked by the selective serotonin 5-HT2A receptor antagonist ketanserin by Franz Vollenweider and colleagues in 1998, solidifying theoretical notions that agonism of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor mediates the hallucinogenic effects of serotonergic psychedelics.[347][359]

Psychedelic renaissance

Since the prohibition of the 1960s and 1970s, clinical research into psychedelics started to resume by the 1990s, for instance the studies of DMT by Rick Strassman, and they have once again started to be developed as pharmaceutical drugs for potential medical use.[268][274][295][360] A so-called "psychedelic renaissance", in which interest in psychedelics has resurged, began in the late 2010s and early 2020s.[361][362][363] Michael Pollan's 2018 book How to Change Your Mind, which was also adapted into a Netflix series in 2022, was especially impactful in terms of increasing mainstream awareness and interest in psychedelics.[364][365][366] More than 100 clinical trials of four major psychedelics, including psilocybin, LSD, ayahuasca, and MDMA, were identified as being underway in 2024.[365][367]

Society and culture

Etymology and nomenclature

The term psychedelic was coined by the psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond during written correspondence with author Aldous Huxley (written in a rhyme: "To fathom Hell or soar angelic/Just take a pinch of psychedelic."[368]) and presented to the New York Academy of Sciences by Osmond in 1957.[369] It is irregularly[370] derived from the Greek words ψυχή (psychḗ, meaning 'mind, soul') and δηλείν (dēleín, meaning 'to manifest'), with the intended meaning "mind manifesting" or alternatively "soul manifesting", and the implication that psychedelics can reveal unused potentials of the human mind.[371] The term was loathed by American ethnobotanist Richard Schultes but championed by American psychologist Timothy Leary.[372]

Aldous Huxley had suggested his own coinage phanerothyme (Greek phaneroein- "to make manifest or visible" and Greek thymos "soul", thus "to reveal the soul") to Osmond in 1956.[373] Recently, the term entheogen (meaning "that which produces the divine within") has come into use to denote the use of psychedelic drugs, as well as various other types of psychoactive substances, in a religious, spiritual, and mystical context.[4]

In 2004, David E. Nichols wrote the following about the nomenclature used for psychedelic drugs:[4]

Many different names have been proposed over the years for this drug class. The famous German toxicologist Louis Lewin used the name phantastica earlier in this century, and as we shall see later, such a descriptor is not so farfetched. The most popular names—hallucinogen, psychotomimetic, and psychedelic ("mind manifesting")—have often been used interchangeably. Hallucinogen is now, however, the most common designation in the scientific literature, although it is an inaccurate descriptor of the actual effects of these drugs. In the lay press, the term psychedelic is still the most popular and has held sway for nearly four decades. Most recently, there has been a movement in nonscientific circles to recognize the ability of these substances to provoke mystical experiences and evoke feelings of spiritual significance. Thus, the term entheogen, derived from the Greek word entheos, which means "god within", was introduced by Ruck et al. and has seen increasing use. This term suggests that these substances reveal or allow a connection to the "divine within". Although it seems unlikely that this name will ever be accepted in formal scientific circles, its use has dramatically increased in the popular media and on internet sites. Indeed, in much of the counterculture that uses these substances, entheogen has replaced psychedelic as the name of choice and we may expect to see this trend continue.

Robin Carhart-Harris and Guy Goodwin write that the term psychedelic is preferable to hallucinogen for describing classical psychedelics because of the term hallucinogen's "arguably misleading emphasis on these compounds' hallucinogenic properties."[374]

While the term psychedelic is most commonly used to refer only to serotonergic hallucinogens,[5][13][375][57] it is sometimes used for a much broader range of drugs, including entactogens, dissociatives, and atypical hallucinogens/psychoactives such as Amanita muscaria, Cannabis sativa, Nymphaea nouchali and Salvia divinorum.[24][376] Thus, the term serotonergic psychedelic is sometimes used for the narrower class.[377][378] It is important to check the definition of a given source.[4] This article uses the more common, narrower definition of psychedelic.

Surrounding culture

Psychedelic culture includes manifestations such as psychedelic music,[379] psychedelic art,[380] psychedelic literature,[381] psychedelic film,[382] and psychedelic festivals.[383] Examples of psychedelic music are found in the work of 1960s rock bands like the Grateful Dead, Jefferson Airplane, The 13th Floor Elevators, and Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd. Many psychedelic bands and elements of the psychedelic subculture originated in San Francisco during the mid to late 1960s.[384]

Legal status

Many psychedelics are classified under Schedule I of the United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971 as drugs with the greatest potential to cause harm and no acceptable medical uses.[385] In addition, many countries have analogue laws; for example, in the United States, the Federal Analogue Act of 1986 automatically forbids any drugs sharing similar chemical structures or chemical formulas to prohibited substances if sold for human consumption.[386]

In July 2022, though, under the United States Food and Drug Administration, the drug psilocybin was on track to be approved of as a treatment for depression, and MDMA as a treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder.[387]

U.S. states such as Oregon and Colorado have also instituted decriminalization and legalization measures for accessing psychedelics[388] and states like New Hampshire are attempting to do the same.[389] J.D. Tuccille argues that increasing rates of use of psychedelics in defiance of the law are likely to result in more widespread legalization and decriminalization of access to the substances in the United States (as has happened with alcohol and cannabis).[390]

Research

Therapeutic effects

Psychedelic substances which may have therapeutic uses include psilocybin, LSD, and mescaline.[25] During the 1950s and 1960s, lack of informed consent in some scientific trials on psychedelics led to significant, long-lasting harm to some participants.[25] Since then, research regarding the effectiveness of psychedelic therapy has been conducted under strict ethical guidelines, with fully informed consent and a pre-screening to avoid people with psychosis taking part.[25] Psychedelics, particularly psilocybin, show potential therapeutic benefits for depression, anxiety, and other mental disorders, with generally mild and transient adverse effects.[391]

It has long been known that psychedelics promote neurite growth and neuroplasticity and are potent psychoplastogens.[392][393][394] There is evidence that psychedelics induce molecular and cellular adaptations related to neuroplasticity and that these could potentially underlie therapeutic benefits.[395][396]

The British critical psychiatrist Joanna Moncrieff has critiqued the use and study of psychedelic and related drugs like psilocybin, MDMA, and ketamine for treatment of psychiatric disorders, highlighting concerns including excessive hype around these drugs, questionable biologically-based theories of benefit, blurred lines between medical and recreational use, flawed clinical trial findings, financial conflicts of interest, strong expectancy effects and large placebo responses, small and short-term benefits over placebo, and their potential for difficult experiences and adverse effects.[397]

See also

- Bwiti

- Cognitive liberty

- Concord Prison Experiment

- Designer drug

- Dissociative drug

- Deliriant

- Drug harmfulness

- Hallucinogenic fish

- Hallucinogenic plants in Chinese herbals

- Hamilton's Pharmacopeia

- Ibogaine

- List of psychedelic chemists

- Marsh Chapel Experiment

- Mystical psychosis

- Psychedelia

- REBUS, neurological model

- Serotonergic cell groups

- Tabernanthe iboga

- Trip killer

- Trip report

References

Further reading

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Winstock, Ar; Timmerman, C; Davies, E; Maier, Lj; Zhuparris, A; Ferris, Ja; Barratt, Mj; Kuypers, Kpc (2021). Global Drug Survey (GDS) 2020 Psychedelics Key Findings Report.

External links

- Psychedelic Timeline - Tom Frame - Psychedelic Times

- Psychedelic drugs - Massviews Analysis - Wikipedia

Template:Psychedelics Template:Major Drug Groups Template:Drug use Template:Serotonin receptor modulators Template:Chemical classes of psychoactive drugs

KSF

KSF![Synthetic mescaline. This psychedelic was the first to be isolated.[42]](https://handwiki.org/wiki/images/thumb/c/cf/Synthetic_mescaline_powder_i2001e0151_ccby3.jpg/154px-Synthetic_mescaline_powder_i2001e0151_ccby3.jpg)