Settling

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 7 min

Settling is the process by which particulates move towards the bottom of a liquid and form a sediment. Particles that experience a force, either due to gravity or due to centrifugal motion will tend to move in a uniform manner in the direction exerted by that force. For gravity settling, this means that the particles will tend to fall to the bottom of the vessel, forming sludge or slurry at the vessel base. Settling is an important operation in many applications, such as mining, wastewater and drinking water treatment, biological science, space propellant reignition,[1] and scooping.

Physics

For settling particles that are considered individually, i.e. dilute particle solutions, there are two main forces enacting upon any particle. The primary force is an applied force, such as gravity, and a drag force that is due to the motion of the particle through the fluid. The applied force is usually not affected by the particle's velocity, whereas the drag force is a function of the particle velocity.

For a particle at rest no drag force will be exhibited, which causes the particle to accelerate due to the applied force. When the particle accelerates, the drag force acts in the direction opposite to the particle's motion, retarding further acceleration, in the absence of other forces drag directly opposes the applied force. As the particle increases in velocity eventually the drag force and the applied force will approximately equate, causing no further change in the particle's velocity. This velocity is known as the terminal velocity, settling velocity or fall velocity of the particle. This is readily measurable by examining the rate of fall of individual particles.

The terminal velocity of the particle is affected by many parameters, i.e. anything that will alter the particle's drag. Hence the terminal velocity is most notably dependent upon grain size, the shape (roundness and sphericity) and density of the grains, as well as to the viscosity and density of the fluid.

Single particle drag

Stokes' drag

For dilute suspensions, Stokes' law predicts the settling velocity of small spheres in fluid, either air or water. This originates due to the strength of viscous forces at the surface of the particle providing the majority of the retarding force. Stokes' law finds many applications in the natural sciences, and is given by:

where w is the settling velocity, ρ is density (the subscripts p and f indicate particle and fluid respectively), g is the acceleration due to gravity, r is the radius of the particle and μ is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid.

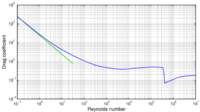

Stokes' law applies when the Reynolds number, Re, of the particle is less than 0.1. Experimentally Stokes' law is found to hold within 1% for , within 3% for and within 9% .[2] With increasing Reynolds numbers, Stokes law begins to break down due to the increasing importance of fluid inertia, requiring the use of empirical solutions to calculate drag forces.

Newtonian drag

Defining a drag coefficient, , as the ratio of the force experienced by the particle divided by the impact pressure of the fluid, a coefficient that can be considered as the transfer of available fluid force into drag is established. In this region the inertia of the impacting fluid is responsible for the majority of force transfer to the particle.

For a spherical particle in the Stokes regime this value is not constant, however in the Newtonian drag regime the drag on a sphere can be approximated by a constant, 0.44. This constant value implies that the efficiency of transfer of energy from the fluid to the particle is not a function of fluid velocity.

As such the terminal velocity of a particle in a Newtonian regime can again be obtained by equating the drag force to the applied force, resulting in the following expression

Transitional drag

In the intermediate region between Stokes drag and Newtonian drag, there exists a transitional regime, where the analytical solution to the problem of a falling sphere becomes problematic. To solve this, empirical expressions are used to calculate drag in this region. One such empirical equation is that of Schiller and Naumann, and may be valid for :[3]

Hindered settling

Stokes, transitional and Newtonian settling describe the behaviour of a single spherical particle in an infinite fluid, known as free settling. However this model has limitations in practical application. Alternate considerations, such as the interaction of particles in the fluid, or the interaction of the particles with the container walls can modify the settling behaviour. Settling that has these forces in appreciable magnitude is known as hindered settling. Subsequently, semi-analytic or empirical solutions may be used to perform meaningful hindered settling calculations.

Applications

The solid-gas flow systems are present in many industrial applications, as dry, catalytic reactors, settling tanks, pneumatic conveying of solids, among others. Obviously, in industrial operations the drag rule is not simple as a single sphere settling in a stationary fluid. However, this knowledge indicates how drag behaves in more complex systems, which are designed and studied by engineers applying empirical and more sophisticated tools.

For example, 'settling tanks' are used for separating solids and/or oil from another liquid. In food processing, the vegetable is crushed and placed inside of a settling tank with water. The oil floats to the top of the water then is collected. In drinking water and waste water treatment a flocculant or coagulant is often added prior to settling to form larger particles that settle out quickly in a settling tank or (lamella) clarifier, leaving the water with a lower turbidity.

In winemaking, the French term for this process is débourbage. This step usually occurs in white wine production before the start of fermentation.[4]

Settleable solids analysis

Settleable solids are the particulates that settle out of a still fluid. Settleable solids can be quantified for a suspension using an Imhoff cone. The standard Imhoff cone of transparent glass or plastic holds one liter of liquid and has calibrated markings to measure the volume of solids accumulated in the bottom of the conical container after settling for one hour. A standardized Imhoff cone procedure is commonly used to measure suspended solids in wastewater or stormwater runoff. The simplicity of the method makes it popular for estimating water quality. To numerically gauge the stability of suspended solids and predict agglomeration and sedimentation events, zeta potential is commonly analyzed. This parameter indicates the electrostatic repulsion between solid particles and can be used to predict whether aggregation and settling will occur over time.

The water sample to be measured should be representative of the total stream. Samples are best collected from the discharge falling from a pipe or over a weir, because samples skimmed from the top of a flowing channel may fail to capture larger, high-density solids moving along the bottom of the channel. The sampling bucket is vigorously stirred to uniformly re-suspend all collected solids immediately before pouring the volume required to fill the cone. The filled cone is immediately placed in a stationary holding rack to allow quiescent settling. The rack should be located away from heating sources, including direct sunlight, which might cause currents within the cone from thermal density changes of the liquid contents. After 45 minutes of settling, the cone is partially rotated about its axis of symmetry just enough to dislodge any settled material adhering to the side of the cone. Accumulated sediment is observed and measured fifteen minutes later, after one hour of total settling time.[5]

See also

- Drag equation – Equation for the force of drag

- Chemistry:Zeta potential – Electrokinetic potential in colloidal dispersions

- Sedimentation – Tendency for particles in suspension to settle down

- Chemistry:Settling basin

- Chemistry:Suspension – Heterogeneous mixture of solid particles dispersed in a medium

- Earth:Total suspended solids – Water quality parameter

References

- ↑ Zegler, Frank; Bernard Kutter (2010-09-02). "Evolving to a Depot-Based Space Transportation Architecture". AIAA SPACE 2010 Conference & Exposition. AIAA. Archived from the original on 2013-05-10. https://web.archive.org/web/20130510002706/http://www.ulalaunch.com/site/docs/publications/DepotBasedTransportationArchitecture2010.pdf. Retrieved 2011-01-25. "It consumes waste hydrogen and oxygen to produce power, generate settling and attitude control thrust."

- ↑ Martin Rhodes. Introduction to Particle Technology.

- ↑ Chemical Engineering. 2. Pergamon press. 1955.

- ↑ Robinson, J. (ed) (2006) "The Oxford Companion to Wine" Third Edition p. 223 Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-860990-6

- ↑ Franson, Mary Ann (1975) Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater 14th edition, APHA, AWWA & WPCF ISBN 0-87553-078-8 pp. 89–91, 95–96

External links

- Settleable solids methodology

- Stokes Law terminal velocity calculator

- Terminal settling velocity calculator for all Reynolds Numbers

- Hindered settling, design of a continuous thickener by Coe and Clevenger

|

KSF

KSF