Texture

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

In physical chemistry[unreliable source?] and materials science, texture is the distribution of crystallographic orientations of a polycrystalline sample (it is also part of the geological fabric). A sample in which these orientations are fully random is said to have no distinct texture. If the crystallographic orientations are not random, but have some preferred orientation, then the sample has a weak, moderate or strong texture. The degree is dependent on the percentage of crystals having the preferred orientation.

Texture is seen in almost all engineered materials, and can have a great influence on materials properties. The texture forms in materials during thermo-mechanical processes, for example during production processes e.g. rolling. Consequently, the rolling process is often followed by a heat treatment to reduce the amount of unwanted texture. Controlling the production process in combination with the characterization of texture and the material's microstructure help to determine the materials properties, i.e. the processing-microstructure-texture-property relationship.[2][3][4] Also, geologic rocks show texture due to their thermo-mechanic history of formation processes.

One extreme case is a complete lack of texture: a solid with perfectly random crystallite orientation will have isotropic properties at length scales sufficiently larger than the size of the crystallites. The opposite extreme is a perfect single crystal, which likely has anisotropic properties by geometric necessity.

Characterization and representation

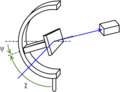

Texture can be determined by various methods.[5] Some methods allow a quantitative analysis of the texture, while others are only qualitative. Among the quantitative techniques, the most widely used is X-ray diffraction using texture goniometers, followed by the electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) method in scanning electron microscopes. Qualitative analysis can be done by Laue photography, simple X-ray diffraction or with a polarized microscope. Neutron and synchrotron high-energy X-ray diffraction are suitable for determining textures of bulk materials and in situ analysis, whereas laboratory x-ray diffraction instruments are more appropriate for analyzing textures of thin films.

Texture is often represented using a pole figure, in which a specified crystallographic axis (or pole) from each of a representative number of crystallites is plotted in a stereographic projection, along with directions relevant to the material's processing history. These directions define the so-called sample reference frame and are, because the investigation of textures started from the cold working of metals, usually referred to as the rolling direction RD, the transverse direction TD and the normal direction ND. For drawn metal wires the cylindrical fiber axis turned out as the sample direction around which preferred orientation is typically observed (see below).

-

Four circles diffractometer, or Eulerian cradle, for texture measurement with X-ray diffraction

-

χ mode for reflection measurement

-

Ω mode for transmission measurement

Common textures

There are several textures that are commonly found in processed (cubic) materials. They are named either by the scientist that discovered them, or by the material they are most found in. These are given in Miller indices for simplification purposes.

- Cube component: (001)[100]

- Brass component: (110)[-112]

- Copper component: (112)[11-1]

- S component: (123)[63-4]

Orientation distribution function

The full 3D representation of crystallographic texture is given by the orientation distribution function (ODF) which can be achieved through evaluation of a set of pole figures or diffraction patterns. Subsequently, all pole figures can be derived from the ODF.

The ODF is defined as the volume fraction of grains with a certain orientation .

The orientation is normally identified using three Euler angles. The Euler angles then describe the transition from the sample’s reference frame into the crystallographic reference frame of each individual grain of the polycrystal. One thus ends up with a large set of different Euler angles, the distribution of which is described by the ODF.

The orientation distribution function, ODF, cannot be measured directly by any technique. Traditionally both X-ray diffraction and EBSD may collect pole figures. Different methodologies exist to obtain the ODF from the pole figures or data in general. They can be classified based on how they represent the ODF. Some represent the ODF as a function, sum of functions or expand it in a series of harmonic functions. Others, known as discrete methods, divide the ODF space in cells and focus on determining the value of the ODF in each cell.

Origins

In wire and fiber, all crystals tend to have nearly identical orientation in the axial direction, but nearly random radial orientation. The most familiar exceptions to this rule are fiberglass, which has no crystal structure, and carbon fiber, in which the crystalline anisotropy is so great that a good-quality filament will be a distorted single crystal with approximately cylindrical symmetry (often compared to a jelly roll). Single-crystal fibers are also not uncommon.

The making of metal sheet often involves compression in one direction and, in efficient rolling operations, tension in another, which can orient crystallites in both axes by a process known as grain flow. However, cold work destroys much of the crystalline order, and the new crystallites that arise with annealing usually have a different texture. Control of texture is extremely important in the making of silicon steel sheet for transformer cores (to reduce magnetic hysteresis) and of aluminium cans (since deep drawing requires extreme and relatively uniform plasticity).

Texture in ceramics usually arises because the crystallites in a slurry have shapes that depend on crystalline orientation, often needle- or plate-shaped. These particles align themselves as water leaves the slurry, or as clay is formed.

Casting or other fluid-to-solid transitions (i.e., thin-film deposition) produce textured solids when there is enough time and activation energy for atoms to find places in existing crystals, rather than condensing as an amorphous solid or starting new crystals of random orientation. Some facets of a crystal (often the close-packed planes) grow more rapidly than others, and the crystallites for which one of these planes faces in the direction of growth will usually out-compete crystals in other orientations. In the extreme, only one crystal will survive after a certain length: this is exploited in the Czochralski process (unless a seed crystal is used) and in the casting of turbine blades and other creep-sensitive parts.

Texture and materials properties

Material properties such as strength,[6] chemical reactivity,[7] stress corrosion cracking resistance,[8] weldability,[9] deformation behavior,[6][7] resistance to radiation damage,[10][11] and magnetic susceptibility[12] can be highly dependent on the material’s texture and related changes in microstructure. In many materials, properties are texture-specific, and development of unfavorable textures when the material is fabricated or in use can create weaknesses that can initiate or exacerbate failures.[6][7] Parts can fail to perform due to unfavorable textures in their component materials.[7][12] Failures can correlate with the crystalline textures formed during fabrication or use of that component.[6][9] Consequently, consideration of textures that are present in and that could form in engineered components while in use can be a critical when making decisions about the selection of some materials and methods employed to manufacture parts with those materials.[6][9] When parts fail during use or abuse, understanding the textures that occur within those parts can be crucial to meaningful interpretation of failure analysis data.[6][7]

Thin film textures

As the result of substrate effects producing preferred crystallite orientations, pronounced textures tend to occur in thin films.[13] Modern technological devices to a large extent rely on polycrystalline thin films with thicknesses in the nanometer and micrometer ranges. This holds, for instance, for all microelectronic and most optoelectronic systems or sensoric and superconducting layers. Most thin film textures may be categorized as one of two different types: (1) for so-called fiber textures the orientation of a certain lattice plane is preferentially parallel to the substrate plane; (2) in biaxial textures the in-plane orientation of crystallites also tend to align with respect to the sample. The latter phenomenon is accordingly observed in nearly epitaxial growth processes, where certain crystallographic axes of crystals in the layer tend to align along a particular crystallographic orientation of the (single-crystal) substrate.

Tailoring the texture on demand has become an important task in thin film technology. In the case of oxide compounds intended for transparent conducting films or surface acoustic wave (SAW) devices, for instance, the polar axis should be aligned along the substrate normal.[14] Another example is given by cables from high-temperature superconductors that are being developed as oxide multilayer systems deposited on metallic ribbons.[15] The adjustment of the biaxial texture in YBa2Cu3O7−δ layers turned out as the decisive prerequisite for achieving sufficiently large critical currents.[16]

The degree of texture is often subjected to an evolution during thin film growth[17] and the most pronounced textures are only obtained after the layer has achieved a certain thickness. Thin film growers thus require information about the texture profile or the texture gradient in order to optimize the deposition process. The determination of texture gradients by x-ray scattering, however, is not straightforward, because different depths of a specimen contribute to the signal. Techniques that allow for the adequate deconvolution of diffraction intensity were developed only recently.[18][19]

References

- ↑ "High energy X-rays: A tool for advanced bulk investigations in materials science and physics". Textures Microstruct. 35 (3/4): 219–52. 2003. doi:10.1080/07303300310001634952.

- ↑ Bahl, Sumit; Nithilaksh, P. L.; Suwas, Satyam; Kailas, Satish V.; Chatterjee, Kaushik (2017). "Processing–Microstructure–Crystallographic Texture–Surface Property Relationships in Friction Stir Processing of Titanium" (in en). Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance 26 (9): 4206–4216. doi:10.1007/s11665-017-2865-6. ISSN 1059-9495. Bibcode: 2017JMEP...26.4206B. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11665-017-2865-6.

- ↑ Proceedings of the International Conference on microstructure and texture in steels and other materials ; February 5-7, 2008, Jamshedpur, India. Arunansu Haldar, Satyam Suwas, Debashish Bhattacharjee, Tata Iron and Steel Company, Indian Institute of Metals. London: Springer. 2009. ISBN 978-1-84882-454-6. OCLC 489216165. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/489216165.

- ↑ Murty, S. V. S. Narayana; Nayan, Niraj; Kumar, Pankaj; Narayanan, P. Ramesh; Sharma, S. C.; George, Koshy M. (2014-01-01). "Microstructure–texture–mechanical properties relationship in multi-pass warm rolled Ti–6Al–4V Alloy" (in en). Materials Science and Engineering: A 589: 174–181. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2013.09.087. ISSN 0921-5093. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0921509313010812.

- ↑ H.-R. Wenk; P. Van Houtte (2004). "Texture and anisotropy". Rep. Prog. Phys. 67 (8): 1367–1428. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/67/8/R02. Bibcode: 2004RPPh...67.1367W.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 O. Engler; V. Randle (2009). Introduction to Texture Analysis: Macrotexture, Microtexture, and Orientation Mapping, Second Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6365-3.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 U. F. Kocks, C. N. Tomé, H. -R. Wenk and H. Mecking (2000). Texture and Anisotropy: Preferred Orientations in Polycrystals and their effects on Materials Properties.. Cambridge University Press.. ISBN 978-0-521-79420-6.

- ↑ D. B. Knorr, J. M. Peltier, and R. M. Pelloux, "Influence of Crystallographic Texture and Test Temperature on Initiation and Propagation of Iodine Stress-Corrosion Cracks in Zircaloy" (1972). Zirconium in the Nuclear Industry: Sixth International Symposium. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM. pp. 627–651.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Peter Rudling; A. Strasser; F. Garzarolli. (2007). Welding of Zirconium Alloys. Sweden: Advanced Nuclear Technology International. pp. 4–3(4–13). http://www.antinternational.com/fileadmin/Products_and_handbooks/IZNA/First_chapter_IZNA_7_STR_Weld.pdf.

- ↑ Y. S. Kim; H. K. Woo; K. S. Im; S. I. Kwun (2002). The Cause for Enhanced Corrosion of Zirconium Alloys by Hydrides. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM. 277. ISBN 978-0-8031-2895-8.

- ↑ Brachet J.; Portier L.; Forgeron T.; Hivroz J.; Hamon D.; Guilbert T.; Bredel T.; Yvon P. et al. (2002). Influence of Hydrogen Content on the α/β Phase Transformation Temperatures and on the Thermal-Mechanical Behavior of Zy-4, M4 (ZrSnFeV), and M5™ (ZrNbO) Alloys During the First Phase of LOCA Transient. Philadelphia, PA: ASTM. 685. ISBN 978-0-8031-2895-8.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 B. C. Cullity (1956). Elements of X-Ray Diffraction. United States of America: Addison-Wesley. pp. 273–274. https://archive.org/details/elementsofxraydi00cull.

- ↑ Highly oriented TiO2 films on quartz substrates Surface coatings and technology

- ↑ M. Birkholz, B. Selle, F. Fenske and W. Fuhs (2003). "Structure-Function Relationship between Preferred Orientation of Crystallites and Electrical Resistivity in Thin Polycrystalline ZnO:Al Films". Phys. Rev. B 68 (20): 205414. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.68.205414. Bibcode: 2003PhRvB..68t5414B.

- ↑ A. Goyal, M. Parans Paranthaman and U. Schoop (2004). "The RABiTS Approach: Using Rolling-Assisted Biaxially Textured Substrates for High-Performance YBCO Superconductors". MRS Bull. 29 (August): 552–561. doi:10.1557/mrs2004.161.

- ↑ Y. Iijima, K. Kakimoto, Y. Yamada, T. Izumi, T. Saitoh and Y. Shiohara (2004). "Research and Development of Biaxially Textured IBAD-GZO Templates for Coated Superconductors". MRS Bull. 29 (August): 564–571. doi:10.1557/mrs2004.162.

- ↑ F. Fenske, B. Selle, M. Birkholz (2005). "Preferred Orientation and Anisotropic Growth in Polycrystalline ZnO:Al Films Prepared by Magnetron Sputtering". Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. Lett. 44 (21): L662–L664. doi:10.1143/JJAP.44.L662. Bibcode: 2005JaJAP..44L.662F. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/40829388.

- ↑ J. Bonarski (2006). "X-ray texture tomography of near-surface areas". Progress in Materials Science 51: 61–149. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2005.05.001.

- ↑ M. Birkholz (2007). "Modelling of diffraction from fiber texture gradients in thin polycrystalline films". J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40 (4): 735–742. doi:10.1107/S0021889807027240. Bibcode: 2007JApCr..40..735B. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/200045406.

Further reading

- Bunge, H.-J. "Mathematische Methoden der Texturanalyse" (1969) Akademie-Verlag, Berlin

- Bunge, H.-J. "Texture Analysis in Materials Science" (1983) Butterworth, London

- Kocks, U. F., Tomé, C. N., Wenk, H.-R., Beaudoin, A. J., Mecking, H. "Texture and Anisotropy – Preferred Orientations in Polycrystals and Their Effect on Materials Properties" (2000) Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-79420-X

- Birkholz, M., chapter 5 of "Thin Film Analysis by X-ray Scattering" (2006) Wiley-VCH, Weinheim ISBN 3-527-31052-5

External links

- aluMatter: Representing Texture

- MTEX MATLAB toolbox for Texture Analysis

- Labotex, ODF/texture analysis software for Microsoft Windows

- Crystallographic Texture

- Combined Analysis

KSF

KSF