Tryptamine

Topic: Chemistry

From HandWiki - Reading time: 22 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 22 min

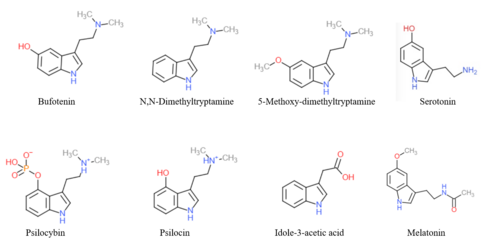

Tryptamine is an indolamine metabolite of the essential amino acid tryptophan.[1][2] The chemical structure is defined by an indole—a fused benzene and pyrrole ring, and a 2-aminoethyl group at the second carbon (third aromatic atom, with the first one being the heterocyclic nitrogen).[1] The structure of tryptamine is a shared feature of certain aminergic neuromodulators including melatonin, serotonin, bufotenin and psychedelic derivatives such as dimethyltryptamine (DMT), psilocybin, psilocin and others.[3][4][5]

Tryptamine has been shown to activate serotonin receptors[6][7] and trace amine-associated receptors expressed in the mammalian brain, and regulates the activity of dopaminergic, serotonergic and glutamatergic systems.[8][9] In the human gut, bacteria convert dietary tryptophan to tryptamine, which activates 5-HT4 receptors and regulates gastrointestinal motility.[2][10][11]

Multiple tryptamine-derived drugs have been developed to treat migraines, while trace amine-associated receptors are being explored as a potential treatment target for neuropsychiatric disorders.[12][13][14]

Natural occurrences

For a list of plants, fungi and animals containing tryptamines, see List of psychoactive plants and List of naturally occurring tryptamines.

Mammalian brain

Endogenous levels of tryptamine in the mammalian brain are less than 100 ng per gram of tissue.[4][9] However, elevated levels of trace amines have been observed in patients with certain neuropsychiatric disorders taking medications, such as bipolar depression and schizophrenia.[15]

Mammalian gut microbiome

Tryptamine is relatively abundant in the gut and feces of humans and rodents.[2][10] Commensal bacteria, including Ruminococcus gnavus and Clostridium sporogenes in the gastrointestinal tract, possess the enzyme tryptophan decarboxylase, which aids in the conversion of dietary tryptophan to tryptamine.[2] Tryptamine is a ligand for gut epithelial serotonin type 4 (5-HT4) receptors and regulates gastrointestinal electrolyte balance through colonic secretions.[10]

Metabolism

Biosynthesis

To yield tryptamine in vivo, tryptophan decarboxylase removes the carboxylic acid group on the α-carbon of tryptophan.[4] Synthetic modifications to tryptamine can produce serotonin and melatonin; however, these pathways do not occur naturally as the main pathway for endogenous neurotransmitter synthesis.[16]

Catabolism

Monoamine oxidases A and B are the primary enzymes involved in tryptamine metabolism to produce indole-3-acetaldehyde, however it is unclear which isoform is specific to tryptamine degradation.[17]

Figure

Biological activity

| Target | Affinity (Ki, nM) | Species |

|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | 32–105 (Ki) 899–>10,000 (EC50) ND (Emax) |

Human Human Human |

| 5-HT1B | 36–525 | Human |

| 5-HT1D | 23–521 | Human |

| 5-HT1E | 2,559 | Human |

| 5-HT1F | 2,409 | Human |

| 5-HT2A | 37–4,070 (Ki) 7.4–257 (EC50) 71–104% (Emax) |

Human Human Human |

| 5-HT2B | 25–113 (Ki) 29.5 (EC50) 92% (Emax) |

Human Human Human |

| 5-HT2C | 17–3,000 (Ki) 1.17–45.7 (EC50) 85–108% (Emax) |

Human Human Human |

| 5-HT3 | ND | ND |

| 5-HT4 | >10,000 13,500 (EC50) 96% (Emax) |

Mouse Pig Pig |

| 5-HT5A | ND | ND |

| 5-HT6 | 70–438 | Human |

| 5-HT7 | 148–158 | Human |

| α2A | 19,000 | Rat |

| TAAR1 | 1,400 (Ki) 2,700 (EC50) 117% (Emax) 130 (Ki) 410 (EC50) 91% (Emax) 1,084 (Ki) 2,210–21,000 (EC50) 73% (Emax) |

Mouse Mouse Mouse Rat Rat Rat Human Human Human |

| SERT | 32.6 (EC50) a | Rat |

| NET | 716 (EC50) a | Rat |

| DAT | 164 (EC50) a | Rat |

| Note: The smaller the value, the more avidly the compound binds to or activates the site. Footnotes: a = Neurotransmitter release. Refs: Main:[18][19] Additional:[20][21][22][6][23][24][25][26][27][28][29] | ||

Serotonin receptor agonist

Tryptamine is known to act as a serotonin receptor agonist, although its potency is limited by rapid inactivation by monoamine oxidases.[30][6][7][31][32][33] It has specifically been found to act as a full agonist of the serotonin 5-HT2A receptor (EC50 = 7.36 ± 0.56 nM; Emax = 104 ± 4%).[6] Tryptamine was of much lower potency in stimulating the 5-HT2A receptor β-arrestin pathway (EC50 = 3,485 ± 234 nM; Emax = 108 ± 16%).[6] In contrast to the 5-HT2A receptor, tryptamine was found to be inactive at the serotonin 5-HT1A receptor.[6]

Gastrointestinal motility

Tryptamine produced by mutualistic bacteria in the human gut activates serotonin GPCRs ubiquitously expressed along the colonic epithelium.[10] Upon tryptamine binding, the activated 5-HT4 receptor undergoes a conformational change which allows its Gs alpha subunit to exchange GDP for GTP, and its liberation from the 5-HT4 receptor and βγ subunit.[10] GTP-bound Gs activates adenylyl cyclase, which catalyzes the conversion of ATP into cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).[10] cAMP opens chloride and potassium ion channels to drive colonic electrolyte secretion and promote intestinal motility.[11][34]

Monoamine releasing agent

Tryptamine has been found to act as a monoamine releasing agent (MRA).[30][6][23] It is a releaser of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, in that order of potency (EC50 = 32.6 nM, 164 nM, and 716 nM, respectively).[30][6][23] That is, it acts as a serotonin–norepinephrine–dopamine releasing agent (SNDRA).[6][23]

| Compound | 5-HT | NE | DA | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptamine | 32.6 | 716 | 164 | [6][23] | ||

| Serotonin | 44.4 | >10,000 | ≥1,960 | [35][36] | ||

| Phenethylamine | >10,000 | 10.9 | 39.5 | [37][38][36] | ||

| Tyramine | 2,775 | 40.6 | 119 | [35][36] | ||

| 5-Methoxytryptamine | 2,169 | >10,000 | >10,000 | [23] | ||

| N-Methyltryptamine | 22.4 | 733 | 321 | [6] | ||

| Dimethyltryptamine | 114 | 4,166 | >10,000 | [6] | ||

| Psilocin | 561 | >10,000 | >10,000 | [39][6] | ||

| Bufotenin | 30.5 | >10,000 | >10,000 | [6] | ||

| 5-MeO-DMT | >10,000 | >10,000 | >10,000 | [40] | ||

| α-Methyltryptamine | 21.7–68 | 79–112 | 78.6–180 | [40] | ||

| α-Ethyltryptamine | 23.2 | 640 | 232 | [23] | ||

| D-Amphetamine | 698–1,765 | 6.6–7.2 | 5.8–24.8 | [35][41] | ||

| Notes: The smaller the value, the more strongly the drug releases the neurotransmitter. The assays were done in rat brain synaptosomes and human potencies may be different. See also Monoamine releasing agent § Activity profiles for a larger table with more compounds. Refs:[42][43] | ||||||

Monoaminergic activity enhancer

Tryptamine is a monoaminergic activity enhancer (MAE) of serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine in addition to its serotonin receptor agonism.[44][45] That is, it enhances the action potential-mediated release of these monoamine neurotransmitters.[44][45] The MAE actions of tryptamine and other MAEs may be mediated by TAAR1 agonism.[46][47] Synthetic and more potent MAEs like benzofuranylpropylaminopentane (BPAP) and indolylpropylaminopentane (IPAP) have been derived from tryptamine.[44][45][48][49][50]

TAAR1 agonist

Tryptamine is an agonist of the trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1).[21] It is a potent TAAR1 full agonist in rats, a weak TAAR1 full agonist in mice, and a very weak TAAR1 partial agonist in humans.[21] Tryptamine may act as a trace neuromodulator in some species via activation of TAAR1 signaling.[21][51]

The TAAR1 is a stimulatory G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that is weakly expressed in the intracellular compartment of both pre- and postsynaptic neurons.[9] TAAR1 agonists have been implicated in regulating monoaminergic neurotransmission, for instance by activating G protein-coupled inwardly-rectifying potassium channels (GIRKs) and reducing neuronal firing via facilitation of membrane hyperpolarization through the efflux of potassium ions.[21][52]

TAAR1 agonists are under investigation as a novel treatment for neuropsychiatric conditions like schizophrenia, drug addiction, and depression.[9] The TAAR1 is expressed in brain structures associated with dopamine systems, such as the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and serotonin systems in the dorsal raphe nuclei (DRN).[9] Additionally, the human TAAR1 gene is localized at 6q23.2 on the human chromosome, which is a susceptibility locus for mood disorders and schizophrenia.[21] Activation of TAAR1 suggests a potential novel treatment for neuropsychiatric disorders, as TAAR1 agonists produce antipsychotic-like, anti-addictive, and antidepressant-like effects in animals.[52][21]

| Compound | Human TAAR1 | Mouse TAAR1 | Rat TAAR1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC50 (nM) | Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM) | Ki (nM) | EC50 (nM) | Ki (nM) | |

| Tryptamine | 21,000 | N/A | 2,700 | 1,400 | 410 | 130 |

| Serotonin | >50,000 | N/A | >50,000 | N/A | 5,200 | N/A |

| Psilocin | >30,000 | N/A | 2,700 | 17,000 | 920 | 1,400 |

| Dimethyltryptamine | >10,000 | N/A | 1,200 | 3,300 | 1,500 | 22,000 |

| Notes: (1) EC50 and Ki values are in nanomolar (nM). (2) EC50 reflects the concentration required to elicit 50% of the maximum TAAR1 response. (3) The smaller the Ki value, the stronger the compound binds to the receptor. | ||||||

Effects in animals and humans

In a published clinical study, tryptamine, at a total dose of 23 to 277 mg by intravenous infusion, produced hallucinogenic effects or perceptual disturbances similar to those of small doses of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).[53][54][6][55] It also produced other LSD-like effects, including pupil dilation, increased blood pressure, and increased force of the patellar reflex.[53][6][54][55] Tryptamine produced side effects including nausea, vomiting, dizziness, tingling sensations, sweating, and bodily heaviness among others as well.[53][55] Conversely, there were no changes in heart rate or respiratory rate.[55] The onset of the effects was rapid and the duration was very short.[30][6][54][55] This can be attributed to the very rapid metabolism of tryptamine by monoamine oxidase (MAO) and its very short elimination half-life.[30][6][54][55]

In animals, tryptamine, alone and/or in combination with a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), produces behavioral changes such as hyperlocomotion and reversal of reserpine-induced behavioral depression.[53][30][56][57] In addition, it produces effects like hyperthermia, tachycardia, myoclonus, and seizures or convulsions, among others.[53][30][56][57] Findings on tryptamine and the head-twitch response in rodents have been mixed, with some studies reporting no effect,[58][59] some studies reporting induction of head twitches by tryptamine,[60][61][62] and others reporting that tryptamine actually antagonized 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP)-induced head twitches.[56][58] Another study found that combination of tryptamine with an MAOI dose-dependently produced head twitches.[63] Head twitches in rodents are a behavioral proxy of psychedelic-like effects.[64][65] Many of the effects of tryptamine can be reversed by serotonin receptor antagonists like metergoline, metitepine (methiothepin), and cyproheptadine.[30][56][57][53] Conversely, the effects of tryptamine in animals are profoundly augmented by MAOIs due to inhibition of its metabolism.[30][57][53]

Tryptamine seems to also elevate prolactin and cortisol levels in animals and/or humans.[57]

The LD50 values of tryptamine in animals include 100 mg/kg i.p. in mice, 500 mg/kg s.c. in mice, and 223 mg/kg i.p. in rats.[66]

Pharmacokinetics

Tryptamine produced endogenously or administered peripherally is readily able to cross the blood–brain barrier and enter the central nervous system.[57][56] This is in contrast to serotonin, which is peripherally selective.[57]

Tryptamine is metabolized by monoamine oxidase (MAO) to form indole-3-acetic acid (IAA).[57][30][56] Its metabolism is described as extremely rapid and its elimination half-life and duration as very short.[30][6][54][55] In addition, its duration is described as shorter than that of dimethyltryptamine (DMT).[53] Brain tryptamine levels are increased up to 300-fold by MAOIs in animals.[56] In addition, the effects of exogenous tryptamine are strongly augmented by monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).[30][56]

Tryptamine is excreted in urine and its rate of urinary excretion has been reported to be pH-dependent.[55][67][68]

Chemistry

Tryptamine is a substituted tryptamine derivative and trace amine and is structurally related to the amino acid tryptophan.

The experimental log P of tryptamine is 1.55.[66]

Derivatives

The endogenous monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) and melatonin (5-methoxy-N-acetyltryptamine), as well as trace amines like N-methyltryptamine (NMT), N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), and bufotenin (N,N-dimethylserotonin), are derivatives of tryptamine.

A variety of drugs, including both naturally occurring and pharmaceutical substances, are derivatives of tryptamine. These include the tryptamine psychedelics like psilocybin, psilocin, DMT, and 5-MeO-DMT; tryptamine stimulants, entactogens, psychedelics, and/or antidepressants like α-methyltryptamine (αMT) and α-ethyltryptamine (αET); triptan antimigraine agents like sumatriptan; certain antipsychotics like oxypertine; and the sleep aid melatonin.

Various other drugs, including ergolines and lysergamides like the psychedelic lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), the antimigraine agents ergotamine, dihydroergotamine, and methysergide, and the antiparkinsonian agents bromocriptine, cabergoline, lisuride, and pergolide; β-carbolines like harmine (some of which are monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)); Iboga alkaloids like the hallucinogen ibogaine; yohimbans like the α2 blocker yohimbine; antipsychotics like ciclindole and flucindole; and the MAOI antidepressant metralindole, can all be thought of as cyclized tryptamine derivatives.

Drugs very closely related to tryptamines, but technically not tryptamines themselves, include certain triptans like avitriptan and naratriptan; the antipsychotics sertindole and tepirindole; and the MAOI antidepressants pirlindole and tetrindole.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Tryptamine". https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/1150.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Jenkins, Trisha A.; Nguyen, Jason C. D.; Polglaze, Kate E.; Bertrand, Paul P. (2016-01-20). "Influence of Tryptophan and Serotonin on Mood and Cognition with a Possible Role of the Gut-Brain Axis". Nutrients 8 (1): 56. doi:10.3390/nu8010056. ISSN 2072-6643. PMID 26805875.

- ↑ Tylš, Filip; Páleníček, Tomáš; Horáček, Jiří (2014-03-01). "Psilocybin – Summary of knowledge and new perspectives" (in en). European Neuropsychopharmacology 24 (3): 342–356. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006. ISSN 0924-977X. PMID 24444771. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924977X13003519.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Tittarelli, Roberta; Mannocchi, Giulio; Pantano, Flaminia; Romolo, Francesco Saverio (2015). "Recreational Use, Analysis and Toxicity of Tryptamines". Current Neuropharmacology 13 (1): 26–46. doi:10.2174/1570159X13666141210222409. ISSN 1570-159X. PMID 26074742.

- ↑ "The Ayahuasca Phenomenon" (in en-gb). 21 November 2014. https://maps.org/articles/5408-the-ayahuasca-phenomenon.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 "Interaction of psychoactive tryptamines with biogenic amine transporters and serotonin receptor subtypes". Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231 (21): 4135–4144. October 2014. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3557-7. PMID 24800892. "[Tryptamine (T): [...] Psychoactive effects: Psychoactive, short acting due to metabolism, increased blood pressure, similar to LSD".

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Tryptamine: a metabolite of tryptophan implicated in various neuropsychiatric disorders". Metab Brain Dis 8 (1): 1–44. March 1993. doi:10.1007/BF01000528. PMID 8098507.

- ↑ Khan, Muhammad Zahid; Nawaz, Waqas (2016-10-01). "The emerging roles of human trace amines and human trace amine-associated receptors (hTAARs) in central nervous system" (in en). Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 83: 439–449. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.07.002. ISSN 0753-3322. PMID 27424325. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S075333221630556X.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Berry, Mark D.; Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Hoener, Marius C.; Shahid, Mohammed (2017-12-01). "Pharmacology of human trace amine-associated receptors: Therapeutic opportunities and challenges" (in en). Pharmacology & Therapeutics 180: 161–180. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.002. ISSN 0163-7258. PMID 28723415.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Bhattarai, Yogesh; Williams, Brianna B.; Battaglioli, Eric J.; Whitaker, Weston R.; Till, Lisa; Grover, Madhusudan; Linden, David R.; Akiba, Yasutada et al. (2018-06-13). "Gut Microbiota-Produced Tryptamine Activates an Epithelial G-Protein-Coupled Receptor to Increase Colonic Secretion" (in en). Cell Host & Microbe 23 (6): 775–785.e5. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.004. ISSN 1931-3128. PMID 29902441.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Field, Michael (2003). "Intestinal ion transport and the pathophysiology of diarrhea". Journal of Clinical Investigation 111 (7): 931–943. doi:10.1172/JCI200318326. ISSN 0021-9738. PMID 12671039.

- ↑ "Serotonin Receptor Agonists (Triptans)", LiverTox: Clinical and Research Information on Drug-Induced Liver Injury (Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases), 2012, PMID 31644023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548713/, retrieved 2020-10-15

- ↑ "New Compound Related to Psychedelic Ibogaine Could Treat Addiction, Depression" (in EN). 2020-12-09. https://www.ucdavis.edu/news/new-compound-related-psychedelic-ibogaine-could-treat-addiction-depression.

- ↑ ServiceDec. 9, Robert F.. "Chemists re-engineer a psychedelic to treat depression and addiction in rodents" (in en). https://www.science.org/content/article/chemists-re-engineer-psychedelic-treat-depression-and-addiction-rodents.

- ↑ Miller, Gregory M. (2011). "The Emerging Role of Trace Amine Associated Receptor 1 in the Functional Regulation of Monoamine Transporters and Dopaminergic Activity". Journal of Neurochemistry 116 (2): 164–176. doi:10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. ISSN 0022-3042. PMID 21073468.

- ↑ "Serotonin Synthesis and Metabolism". 2020. https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/technical-documents/articles/biology/rbi-handbook/non-peptide-receptors-synthesis-and-metabolism/serotonin-synthesis-and-metabolism.html.

- ↑ "MetaCyc L-tryptophan degradation VI (via tryptamine)". https://biocyc.org/META/new-image?object=PWY-3181.

- ↑ "PDSP Database" (in zu). https://pdsp.unc.edu/databases/pdsp.php?testFreeRadio=testFreeRadio&testLigand=Tryptamine&kiAllRadio=all&doQuery=Submit+Query.

- ↑ Liu, Tiqing. "BindingDB BDBM50024210 1H-indole-3-ethanamine::2-(1H-indol-3-yl)ethanamine::2-(3-indolyl)ethylamine::CHEMBL6640::tryptamine". https://www.bindingdb.org/rwd/bind/chemsearch/marvin/MolStructure.jsp?monomerid=50024210.

- ↑ "5-HT2 receptor binding, functional activity and selectivity in N-benzyltryptamines". PLOS ONE 14 (1). 2019. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0209804. PMID 30629611. Bibcode: 2019PLoSO..1409804T.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 Gainetdinov, Raul R.; Hoener, Marius C.; Berry, Mark D. (2018-07-01). "Trace Amines and Their Receptors" (in en). Pharmacological Reviews 70 (3): 549–620. doi:10.1124/pr.117.015305. ISSN 0031-6997. PMID 29941461. https://pharmrev.aspetjournals.org/content/70/3/549.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "In Vitro Characterization of Psychoactive Substances at Rat, Mouse, and Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1". J Pharmacol Exp Ther 357 (1): 134–144. April 2016. doi:10.1124/jpet.115.229765. PMID 26791601. https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/74120533/eae6c6e62565b82d46b4d111bbea0f77b9c2-libre.pdf?1635931703=&response-content-disposition=inline%3B+filename%3DIn_Vitro_Characterization_of_Psychoactiv.pdf&Expires=1746838268&Signature=Sy4fJ90yUhxs68314NxYsW5PAaNrBGePRu35WRR4PIF-3YC7Z~sLdnCn5wfqqbLg9bDEGdt~oW55ugMP3D3jgA0BoRI~~GOb0NQOwrtfUEQK1PQs1uuN9qg5Y1ct8z5NsABm44RgtukkwRMdU6fO7OlfIsQ68hOiFk129Ll7UYqldxD2f1xhE2fTTfsxSpb8cMCJzHn7-ItqLdwnAUPFK7WggDIjmY1kCnaHLwIxMwdJCAq8L6DYzSTg7pZkbR8qlou~GXbTPQt~gYpyZTJp5hgW-7V6K5wLlQ7Z2xE7B0f9wEfuc1W1QNafg125Tr-vvAe4LEGKXV58bnn1bpfWKw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAJLOHF5GGSLRBV4ZA.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 "Alpha-ethyltryptamines as dual dopamine-serotonin releasers". Bioorg Med Chem Lett 24 (19): 4754–4758. October 2014. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.07.062. PMID 25193229.

- ↑ "Functional characterization of agonists at recombinant human 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptors in CHO-K1 cells". Br J Pharmacol 128 (1): 13–20. September 1999. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0702751. PMID 10498829.

- ↑ van Wijngaarden, I.; Soudijn, W. (1997). "5-HT2A, 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C receptor ligands". Pharmacochemistry Library. 27. Elsevier. pp. 161–197. doi:10.1016/s0165-7208(97)80013-x. ISBN 978-0-444-82041-9.

- ↑ "A cane toad (Rhinella marina) N-methyltransferase converts primary indolethylamines to tertiary psychedelic amines". J Biol Chem 299 (10). October 2023. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2023.105231. PMID 37690691.

- ↑ Chen, Xue; Li, Jing; Yu, Lisa; Dhananjaya, D; Maule, Francesca; Cook, Sarah; Chang, Limei; Gallant, Jonathan et al. (10 March 2023), Bioproduction platform using a novel cane toad (Rhinella marina) N-methyltransferase for psychedelic-inspired drug discovery, doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2667175/v1, https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-2667175/latest.pdf, retrieved 18 March 2025

- ↑ "Agonist high and low affinity state ratios predict drug intrinsic activity and a revised ternary complex mechanism at serotonin 5-HT(2A) and 5-HT(2C) receptors". Synapse 35 (2): 144–150. February 2000. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(200002)35:2<144::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 10611640.

- ↑ "Characterization of the 5-HT4 receptor mediating tachycardia in piglet isolated right atrium". Br J Pharmacol 110 (3): 1023–1030. November 1993. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13916.x. PMID 8298790.

- ↑ 30.00 30.01 30.02 30.03 30.04 30.05 30.06 30.07 30.08 30.09 30.10 30.11 "Tryptamine: a neuromodulator or neurotransmitter in mammalian brain?". Prog Neurobiol 19 (1–2): 117–139. 1982. doi:10.1016/0301-0082(82)90023-5. PMID 6131482.

- ↑ "Vasoconstrictor and vasodilator responses to tryptamine of rat-isolated perfused mesentery: comparison with tyramine and β-phenylethylamine". Br J Pharmacol 165 (7): 2191–2202. April 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01706.x. PMID 21958009.

- ↑ "Tryptamine-induced vasoconstrictor responses in rat caudal arteries are mediated predominantly via 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors". Br J Pharmacol 84 (4): 919–925. April 1985. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1985.tb17386.x. PMID 3159458.

- ↑ "Central serotonin receptors as targets for drug research". J Med Chem 30 (1): 1–12. January 1987. doi:10.1021/jm00384a001. PMID 3543362. "Table II. Affinities of Selected Phenalkylamines for 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 Binding Sites".

- ↑ "Microbiome-Lax May Relieve Constipation" (in en-US). 2018-06-15. https://www.genengnews.com/topics/omics/microbiome-lax-may-relieve-constipation/.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 "Amphetamine-type central nervous system stimulants release norepinephrine more potently than they release dopamine and serotonin". Synapse 39 (1): 32–41. January 2001. doi:10.1002/1098-2396(20010101)39:1<32::AID-SYN5>3.0.CO;2-3. PMID 11071707.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 "Dopamine-releasing agents". Dopamine Transporters: Chemistry, Biology and Pharmacology. Hoboken [NJ]: Wiley. July 2008. pp. 305–320. ISBN 978-0-470-11790-3. OCLC 181862653. https://bitnest.netfirms.com/external/Books/Dopamine-releasing-agents_c11.pdf.

- ↑ "Behavioral, biological, and chemical perspectives on atypical agents targeting the dopamine transporter". Drug and Alcohol Dependence 147: 1–19. February 2015. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.005. PMID 25548026.

- ↑ Forsyth, Andrea N (22 May 2012). "Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Rigid Analogues of Methamphetamines". https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1436/.

- ↑ "Studies of the biogenic amine transporters. 14. Identification of low-efficacy "partial" substrates for the biogenic amine transporters". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 341 (1): 251–262. April 2012. doi:10.1124/jpet.111.188946. PMID 22271821.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "The effects of non-medically used psychoactive drugs on monoamine neurotransmission in rat brain". European Journal of Pharmacology 559 (2–3): 132–137. March 2007. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.11.075. PMID 17223101.

- ↑ "Powerful cocaine-like actions of 3,4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), a principal constituent of psychoactive 'bath salts' products". Neuropsychopharmacology 38 (4): 552–562. 2013. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.204. PMID 23072836.

- ↑ "Monoamine transporters and psychostimulant drugs". Eur J Pharmacol 479 (1–3): 23–40. October 2003. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2003.08.054. PMID 14612135.

- ↑ "Therapeutic potential of monoamine transporter substrates". Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 6 (17): 1845–1859. 2006. doi:10.2174/156802606778249766. PMID 17017961. https://zenodo.org/record/1235860.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "Pharmacological studies with endogenous enhancer substances: beta-phenylethylamine, tryptamine, and their synthetic derivatives". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 28 (3): 421–427. May 2004. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2003.11.016. PMID 15093948.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 "Enhancer regulation/endogenous and synthetic enhancer compounds: a neurochemical concept of the innate and acquired drives". Neurochem Res 28 (8): 1275–1297. August 2003. doi:10.1023/a:1024224311289. PMID 12834268.

- ↑ "Enhancer Regulation of Dopaminergic Neurochemical Transmission in the Striatum". Int J Mol Sci 23 (15): 8543. August 2022. doi:10.3390/ijms23158543. PMID 35955676.

- ↑ "Striking Neurochemical and Behavioral Differences in the Mode of Action of Selegiline and Rasagiline". Int J Mol Sci 24 (17). August 2023. doi:10.3390/ijms241713334. PMID 37686140.

- ↑ "Antiaging compounds: (-)deprenyl (selegeline) and (-)1-(benzofuran-2-yl)-2-propylaminopentane, [(-)BPAP, a selective highly potent enhancer of the impulse propagation mediated release of catecholamine and serotonin in the brain"]. CNS Drug Rev 7 (3): 317–45. 2001. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2001.tb00202.x. PMID 11607046.

- ↑ "Structure-activity studies leading to (-)1-(benzofuran-2-yl)-2-propylaminopentane, ((-)BPAP), a highly potent, selective enhancer of the impulse propagation mediated release of catecholamines and serotonin in the brain". Bioorg Med Chem 9 (5): 1197–1212. May 2001. doi:10.1016/s0968-0896(01)00002-5. PMID 11377178.

- ↑ "(-)1-(Benzofuran-2-yl)-2-propylaminopentane, [(-)BPAP, a selective enhancer of the impulse propagation mediated release of catecholamines and serotonin in the brain"]. British Journal of Pharmacology 128 (8): 1723–1732. December 1999. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0702995. PMID 10588928.

- ↑ Zucchi, R; Chiellini, G; Scanlan, T S; Grandy, D K (2006). "Trace amine-associated receptors and their ligands". British Journal of Pharmacology 149 (8): 967–978. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706948. ISSN 0007-1188. PMID 17088868.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Grandy, David K.; Miller, Gregory M.; Li, Jun-Xu (2016-02-01). ""TAARgeting Addiction" The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution". Drug and Alcohol Dependence 159: 9–16. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.014. ISSN 0376-8716. PMID 26644139.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 53.5 53.6 53.7 Martin, W. R.; Sloan, J. W. (1977). "Pharmacology and Classification of LSD-like Hallucinogens". Drug Addiction II. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 305–368. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-66709-1_3. ISBN 978-3-642-66711-4. "MARTIN and SLOAN (1970) found that intravenously infused tryptamine increased blood pressure, dilated pupils, enhanced the patellar reflex, and produced perceptual distortions. [...] Tryptamine, but not DMT, increases locomotor activity in the mouse, while both antagonize reserpine depression (V ANE et al., 1961). [...] In the rat, tryptamine causes backward locomotion, Straub tail, bradypnea and dyspnea, and clonic convulsions (TEDESCHI et al., 1959). [...] Tryptamine produces a variety of changes in the cat causing signs of sympathetic activation including mydriasis, retraction of nictitating membrane, piloerection, motor signs such as extension of limbs and convulsions and affective changes such as hissing and snarling (LAIDLAW, 1912). [...]"

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 54.3 54.4 Shulgin, A. (1997). Tihkal: The Continuation. Transform Press. #53. T. ISBN 978-0-9630096-9-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=jl_ik66IumUC. Retrieved 17 August 2024. "(with 250 mg, intravenously) "Tryptamine was infused intravenously over a period of up to 7.5 minutes. Physical changes included an increases in blood pressure, in the amplitude of the patellar reflex, and in pupillary diameter. The subjective changes are not unlike those seen with small doses of LSD. A point-by-point comparison between the tryptamine and LSD syndromes reveals a close similarity which is consistent with the hypothesis that tryptamine and LSD have a common mode of action.""

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 55.4 55.5 55.6 55.7 "Effects of infused tryptamine in man". Psychopharmacologia 18 (3): 231–237. 1970. doi:10.1007/BF00412669. PMID 4922520.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 56.6 56.7 Kellar, Kenneth J.; Cascio, Caren S. (1986). "Tryptamine and Phenylethylamine Recognition Sites in Brain". Receptor Binding. 4. New Jersey: Humana Press. pp. 119–138. doi:10.1385/0-89603-078-4:119. ISBN 0-89603-078-4.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 57.5 57.6 57.7 Murphy, D. L.; Tamarkin, L.; Garrick, N. A.; Taylor, P. L.; Markey, S. P. (1985). "Trace Indoleamines in the Central Nervous System". Neuropsychopharmacology of the Trace Amines. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. 343–360. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-5010-4_36. ISBN 978-1-4612-9397-2.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "In vivo pharmacological studies on the interactions between tryptamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine". Br J Pharmacol 73 (2): 485–493. June 1981. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb10447.x. PMID 6972243.

- ↑ "The behavioural effects of intravenously administered tryptamine in mice". Neuropharmacology 26 (1): 49–53. January 1987. doi:10.1016/0028-3908(87)90043-8. PMID 3561719.

- ↑ "Animal models of the serotonin syndrome: a systematic review". Behav Brain Res 256: 328–345. November 2013. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2013.08.045. PMID 24004848.

- ↑ "Effect of tryptamine on the behavior of mice". J Pharmacobiodyn 9 (1): 68–73. January 1986. doi:10.1248/bpb1978.9.68. PMID 2940357.

- ↑ "Effects of 5,7-dihydroxytryptamine and 6-hydroxydopamine on head-twitch response induced by serotonin, p-chloroamphetamine, and tryptamine in mice". Psychopharmacology (Berl) 95 (1): 124–131. 1988. doi:10.1007/BF00212780. PMID 3133691.

- ↑ Irons, Jane; Robinson, C. M.; Marsden, C. A. (1984). "5ht Involvement in Tryptamine Induced Behaviour in Mice". Neurobiology of the Trace Amines. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press. pp. 423–427. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-5312-9_35. ISBN 978-1-4612-9781-9.

- ↑ "Head-twitch response in rodents induced by the hallucinogen 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine: a comprehensive history, a re-evaluation of mechanisms, and its utility as a model". Drug Test Anal 4 (7–8): 556–576. 2012. doi:10.1002/dta.1333. PMID 22517680.

- ↑ Kozlenkov, Alexey; González-Maeso, Javier (2013). "Animal Models and Hallucinogenic Drugs". The Neuroscience of Hallucinations. New York, NY: Springer New York. pp. 253–277. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4121-2_14. ISBN 978-1-4614-4120-5.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "Tryptamine". https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/1150.

- ↑ "Tryptamine, N,N-dimethyltryptamine, N,N-dimethyl-5-hydroxytryptamine and 5-methoxytryptamine in human blood and urine". Nature 206 (988): 1052. June 1965. doi:10.1038/2061052a0. PMID 5839067. Bibcode: 1965Natur.206.1052F.

- ↑ "The dependence of tryptamine excretion on urinary pH". Clin Chim Acta 65 (3): 339–342. December 1975. doi:10.1016/0009-8981(75)90259-4. PMID 1161.

External links

- Tryptamine FAQ - Erowid

- Tryptamine - Isomer Design

- Tryptamine - TiHKAL - Erowid

- Tryptamine - TiHKAL - Isomer Design

Template:Chemical classes of psychoactive drugs Template:Chocolate

|

KSF

KSF