Acorn Computers

Topic: Company

From HandWiki - Reading time: 50 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 50 min

| |

| Industry | Computer hardware |

|---|---|

| Fate | Bought by MSDW Investment Holdings Limited |

| Founded | December 1978 |

| Founder |

|

| Defunct | 9 December 2015 |

| Headquarters | Cambridge, England, United Kingdom |

Key people |

|

| Products |

|

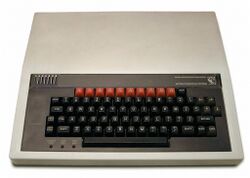

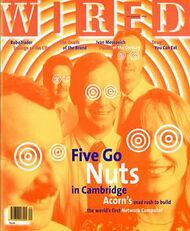

Acorn Computers Ltd. was a British computer company established in Cambridge, England, in 1978. The company produced a number of computers which were especially popular in the United Kingdom , including the Acorn Electron and the Acorn Archimedes. Acorn's BBC Micro computer dominated the UK educational computer market during the 1980s.[1]

Though the company was acquired and largely dismantled in early 1999, with various activities being dispersed amongst new and established companies, its legacy includes the development of reduced instruction set computing (RISC) personal computers. One of its operating systems, RISC OS, continues to be developed by RISC OS Open. Some activities established by Acorn lived on: technology developed by Arm, created by Acorn as a joint venture with Apple and VLSI in 1990, is dominant in the mobile phone and personal digital assistant (PDA) microprocessor market.[2]

Acorn is sometimes referred to as the "British Apple"[3][4] and has been compared to Fairchild Semiconductor for being a catalyst for start-ups.[5][6] In 2010, the company was listed by David Meyer in ZDNet as number nine in a feature of top ten "Dead IT giants".[7] Many British IT professionals gained their early experiences on Acorns, which were often more technically advanced than commercially successful US hardware.[8]

History

Early history

On 25 July 1961, Clive Sinclair founded Sinclair Radionics to develop and sell electronic devices such as calculators.[citation needed] The failure of the Black Watch wristwatch and the calculator market's move from LEDs to LCDs led to financial problems, and Sinclair approached government body the National Enterprise Board (NEB) for help.[9] After losing control of the company to the NEB, Sinclair encouraged Chris Curry to leave Radionics and get Science of Cambridge (SoC—an early name for Sinclair Research) up and running. In June 1978, SoC launched a microcomputer kit, the MK14, that Curry wanted to develop further, but Sinclair could not be persuaded so Curry resigned.[10] During the development of the MK14, Hermann Hauser, a friend of Curry's, had been visiting SoC's offices and had grown interested in the product.

CPU Ltd. (1978–1983)

Curry and Hauser decided to pursue their joint interest in microcomputers and, on 5 December 1978, they set up Cambridge Processor Unit Ltd. (CPU) as the vehicle with which to do this.[11] CPU soon obtained a consultancy contract to develop a microprocessor-based controller for a fruit machine for Ace Coin Equipment (ACE) of Wales. The ACE project was started at office space obtained at 4a Market Hill in Cambridge. Initially, the ACE controller was based on a National Semiconductor SC/MP microprocessor, but soon the switch to a MOS Technology 6502 was made.

The microcomputer systems

CPU had financed the development of a SC/MP based microcomputer system using the income from its design-and-build consultancy.

This system was launched in January 1979 as the first product of Acorn Computer Ltd., a trading name used by CPU to keep the risks of the two different lines of business separate.

The microcomputer kit was named as Acorn System 75. Acorn was chosen because the microcomputer system was to be expandable and growth-oriented. It also had the attraction of appearing before "Apple Computer" in a telephone directory.[12]

Around this time, CPU and Andy Hopper set up Orbis Ltd. to commercialise the Cambridge Ring networking system Hopper had worked on for his PhD, but it was soon decided to bring him into CPU as a director because he could promote CPU's interests at the University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory.

CPU purchased Orbis, and Hopper's Orbis shares were exchanged for shares in CPU Ltd. CPU's role gradually changed as its Acorn brand grew, and soon CPU was simply the holding company and Acorn was responsible for development work.

At some point, Curry had a disagreement with Sinclair and formally left Science of Cambridge, but did not join the other Acorn employees at Market Hill until a little while later.

The Acorn Microcomputer, later renamed the Acorn System 1, was designed by Sophie Wilson (then Roger Wilson). It was a semi-professional system aimed at engineering and laboratory users, but its price was low enough, at around £80 (equivalent to £320 in 2023),[13] to appeal to the more serious enthusiast as well. It was a very small machine built on two cards, one with an LED display, keypad, and cassette interface (the circuitry to the left of the keypad), and the other with the rest of the computer (including the CPU). Almost all CPU signals were accessible via a Eurocard connector.

The System 2 made it easier to expand the system by putting the CPU card from the System 1 in a 19-inch (480 mm) Eurocard rack that allowed a number of optional additions.[14] The System 2 typically shipped with keyboard controller, external keyboard, a text display interface, and a cassette operating system with built-in BASIC interpreter.

The System 3 moved on by adding floppy disk support,[15] and the System 4 by including a larger case with a second drive.[16] The System 5 was largely similar to the System 4, but included a newer 2 MHz version of the 6502.[17]

The Atom

Development of the Sinclair ZX80 started at Science of Cambridge in May 1979. Learning of this probably prompted Curry to conceive the Atom project to target the consumer market. Curry and another designer, Nick Toop, worked from Curry's home in the Fens on the development of this machine. It was at this time that Acorn Computers Ltd. was incorporated and Curry moved to Acorn full-time.

It was Curry who wanted to target the consumer market. Other factions within Acorn, including the engineers, were happy to be out of that market, considering a home computer to be a rather frivolous product for a company operating in the laboratory equipment market.

To keep costs down and not give the doubters reason to object to the Atom, Curry asked industrial designer Allen Boothroyd to design a case that could also function as an external keyboard for the microcomputer systems.

The internals of the System 3 were placed inside the keyboard, creating a quite typical set-up for an inexpensive home computer of the early 1980s: the relatively successful Acorn Atom.

To facilitate software development, a proprietary local area network had been installed at Market Hill. It was decided to include this, the Econet, in the Atom, and at its launch at a computer show in March 1980, eight networked Atoms were demonstrated with functions that allowed files to be shared, screens to be remotely viewed and keyboards to be remotely slaved.

BBC Micro and the Electron

After the Atom had been released into the market, Acorn contemplated building modern 16-bit processors to replace the Atom. After a great deal of discussion, Hauser suggested a compromise—an improved 6502-based machine with far greater expansion capabilities: the Proton. Acorn's technical staff had not wanted to do the Atom and they now saw the Proton as their opportunity to "do it right".[citation needed]

One of the developments proposed for the Proton was the Tube, a proprietary interface allowing a second processor to be added. This compromise would make for an affordable 6502 machine for the mass market which could be expanded with more sophisticated and expensive processors. The Tube enabled processing to be farmed out to the second processor leaving the 6502 to perform data input/output (I/O). The Tube would later be instrumental in the development of Acorn's ARM processor.[18]

In early 1980, the BBC Further Education department conceived the idea of a computer literacy programme, mostly as a follow-up to an ITV documentary, The Mighty Micro, in which Dr Christopher Evans from the UK National Physical Laboratory predicted the coming microcomputer revolution.[19] It was a very influential documentary—so much so that questions were asked in Parliament. As a result of these questions, the Department of Industry (DoI) became interested in the programme, as did BBC Enterprises, which saw an opportunity to sell a machine to go with the series. BBC Engineering was instructed to draw up an objective specification for a computer to accompany the series.

Eventually, under some pressure from the DoI to choose a British system, the BBC chose the NewBrain from Newbury Laboratories. This selection revealed the extent of the pressure brought to bear on the supposedly independent BBC's computer literacy project—Newbury was owned by the National Enterprise Board, a government agency operating in close collaboration with the DoI. The choice was also somewhat ironic given that the NewBrain started life as a Sinclair Radionics project, and it was Sinclair's preference for developing it over Science of Cambridge's MK14 that led to Curry leaving SoC to found CPU with Hauser.[citation needed] The NEB moved the NewBrain to Newbury after Sinclair left Radionics and went to SoC.

In 1980–1982, the British Department of Education and Science (DES) had begun the Microelectronics Education Programme to introduce microprocessing concepts and educational materials. In 1981, through to 1986, the DoI allocated funding to assist UK local education authorities to supply their schools with a range of computers, the BBC Micro being one of the most popular. Schools were offered 50% of the cost of computers, providing they chose one of three models: BBC Micro, ZX Spectrum or Research Machines 380Z.[20] In parallel, the DES continued to fund more materials for the computers, such as software and applied computing projects, plus teacher training.

Although the NewBrain was under heavy development by Newbury, it soon became clear that they were not going to be able to produce it—certainly not in time for the literacy programme nor to the BBC's specification. The BBC's programmes, initially scheduled for autumn 1981, were moved back to spring 1982. After Curry and Sinclair found out about the BBC's plans, the BBC allowed other manufacturers to submit their proposals. Hauser quickly drafted in Steve Furber (who had been working for Acorn on a voluntary basis since the ACE fruit machine project) and Sophie Wilson to help complete a revised version of the Proton which met the BBC's specifications. BBC visited Acorn and were given a demonstration of the Proton. Shortly afterwards, the literacy programme computer contract was awarded to Acorn, and the Proton was launched in December 1981 as the BBC Micro. In April 1984, Acorn won the Queen's Award for Technology for the BBC Micro. The award paid special tribute to the BBC Micro's advanced design, and it commended Acorn "for the development of a microcomputer system with many innovative features".

In April 1982, Sinclair launched the ZX Spectrum. Curry conceived of the Electron as Acorn's sub-£200 competitor. In many ways a cut-down BBC Micro, it used one Acorn-designed uncommitted logic array (ULA) to reproduce most of the functionality. But problems in producing the ULAs led to short supply, and the Electron, although launched in August 1983, was not on the market in sufficient numbers to capitalise on the 1983 Christmas sales period. Acorn resolved to avoid this problem in 1984 and negotiated new production contracts. Acorn became more known for its BBC Micro model B than for its other products.[21]

In 2008, the Computer Conservation Society organised an event at London's Science Museum to mark the legacy of the BBC Micro. A number of the BBC Micro's principal creators were present, and Sophie Wilson recounted to the BBC how Hermann Hauser tricked her and Steve Furber to agree to create the physical prototype in less than five days.[22] Also in 2008 a number of former staff organised a reunion event to mark the 30th anniversary of the company's formation.[23][24][25][26]

1983–1985: Acorn Computer Group

The BBC Micro sold well—so much so that Acorn's profits rose from £3000 in 1979 to £8.6 million in July 1983. In September 1983, CPU shares were liquidated and Acorn was floated on the Unlisted Securities Market as Acorn Computer Group plc, with Acorn Computers Ltd. as the microcomputer division. With a minimum tender price of 120p, the group came into existence with a market capitalisation of about £135 million.[27] CPU founders Hermann Hauser and Chris Curry's stakes in the new company were worth £64m and £51m, respectively.[28] Ten per cent of the equity was placed on the market, with the money raised from the flotation "mainly" directed towards establishing US and German subsidiaries (the flotation raising around £13.4 million[29]), although some was directed towards research and product development.[30]

By the end of 1984, Acorn Computer Group was organised into several subsidiary companies. Acorn Computers Limited was responsible for the management of the microcomputer business, research and development, and UK sales and marketing, whereas Acorn Computer Corporation and Acorn Computers International Limited dealt with sales to the US and to other international markets respectively. Acorn Computers (Far East) Limited focused on component procurement and manufacturing with some distribution responsibilities in local markets. Acornsoft Limited was responsible for development, production and marketing of software for Acorn's computer range. Vector Marketing Limited was established to handle distribution-related logistics and the increasing customer support burden. As part of Acorn's office automation aspirations, conducting "advanced software research and development", Acorn Research Center Incorporated was established in Palo Alto, California. Acorn Leasing Limited rounded out the portfolio.[31]

New RISC architecture

Even from the time of Acorn's earliest systems, the company was considering how to move on from the 6502 processor, introducing a Motorola 6809 processor card for its System 3 and System 4 models.[32] Several years later in 1985, the Acorn Communicator employed the 16-bit 65816 processor as a step up from the 6502.

The IBM PC was launched on 12 August 1981.[33] Although a version of that machine was aimed at the enthusiast market much like the BBC Micro, its real area of success was business. The successor to the PC, the XT (eXtended Technology) was introduced in early 1983. The success of these machines and the variety of Z80-based CP/M machines in the business sector demonstrated that it was a viable market, especially given that sector's ability to cope with premium prices. The development of a business machine looked like a good idea to Acorn. A development programme was started to create a business computer using Acorn's existing technology: the BBC Micro mainboard, the Tube and second processors to give CP/M, MS-DOS and Unix (Xenix) workstations.

This Acorn Business Computer (ABC) plan required a number of second processors to be made to work with the BBC Micro platform. In developing these, Acorn had to implement the Tube protocols on each processor chosen, in the process finding out, during 1983, that there were no obvious candidates to replace the 6502. Because of many-cycle uninterruptible instructions, for example, the interrupt response times of the Motorola 68000 were too slow to handle the communication protocol that the host 6502-based BBC Micro coped with easily. The National Semiconductor 32016-based model of the ABC range, was developed and later sold in 1985 as the Cambridge Workstation (using the Panos operating system).[34] Advertising for this machine in 1986 included an illustration of an office worker using the workstation. The advert claimed mainframe power at a price of £3,480 (excluding VAT). The main text of the advertisement referred to available mainframe languages, communication capabilities and the alternative option of upgrading a BBC Micro using a coprocessor.[35] The machine had shown Sophie Wilson and Steve Furber the value of memory bandwidth. It also showed that an 8 MHz 32016 was completely trounced in performance terms by a 4 MHz 6502. Furthermore, the Apple Lisa had shown the Acorn engineers that they needed to develop a windowing system; this was not going to be easy with a 2–4 MHz 6502-based system doing the graphics. Acorn would need a new architecture.[citation needed]

Acorn had investigated all of the readily available processors and found them wanting[10] or unavailable to them.[5] After testing all of the available processors and finding them lacking, Acorn decided that it needed a new architecture. Inspired by white papers on the Berkeley RISC project, Acorn seriously considered designing its own processor.[36] A visit to the Western Design Center in the US, where the 6502 was being updated by what was effectively a single-person company, showed Acorn engineers Steve Furber and Sophie Wilson they did not need massive resources and state-of-the-art research and development facilities.[37]

Sophie Wilson set about developing the instruction set, writing a simulation of the processor in BBC BASIC that ran on a BBC Micro with a 6502 second processor. It convinced the Acorn engineers that they were on the right track. Before they could go any further, however, they would need more resources. It was time for Wilson to approach Hauser and explain what was afoot. Once the go-ahead had been given, a small team was put together to implement Wilson's model in hardware.

The official Acorn RISC Machine project started in October 1983,[specify] with Acorn spending £5 million on it by 1987.[38] VLSI Technology, Inc were chosen as silicon partner, since they already supplied Acorn with ROMs and some custom chips. VLSI produced the first ARM silicon on 26 April 1985;[39] it worked first time and came to be known as ARM1. Its first practical application was as a second processor to the BBC Micro, where it was used to develop the simulation software to finish work on the support chips (VIDC, IOC, MEMC) and to speed up the operation of the CAD software used in developing ARM2. The ARM evaluation system was promoted as a means for developers to try the system for themselves. This system was used with a BBC Micro and a PC compatible version was also planned.[clarification needed] Advertising was aimed at those with technical expertise, rather than consumers and the education market, with a number of technical specifications listed in the main text of the adverts.[40] Wilson subsequently coded BBC BASIC in ARM assembly language, and the in-depth knowledge obtained from designing the instruction set allowed the code to be very dense, making ARM BBC BASIC an extremely good test for any ARM emulator.

Such was the secrecy surrounding the ARM CPU project that when Olivetti were negotiating to take a controlling share of Acorn in 1985, they were not told about the development team until after the negotiations had been finalised. In 1992, Acorn once more won the Queen's Award for Technology for the ARM.[41] Acorn's development of their RISC OS operating system required around 200 OS development staff at its peak.[42] Acorn C/C++ was released commercially by Acorn, for developers to use to compile their own applications.

Financial problems

Having become a publicly traded company in 1983 during the home computer boom, Acorn's commercial performance in 1984 proved to be consequential. Many home computer manufacturers struggled to maintain customer enthusiasm, some offering unconvincing follow-up products that failed to appeal to buyers. The more successful manufacturers, like Amstrad, emphasised the bundling of computers with essential peripherals such as monitors and cassette recorders along with value for money. The collapse of the market from the manufacturers' perspective, it was argued, was due to the "neglect of the market by the manufacturers".[43] Market adversity had led to Atari being sold,[44] and Apple nearly went bankrupt.

The Electron had been launched in 1983, but problems with the supply of its ULA meant that Acorn was not able to capitalise on the 1983 Christmas selling period.[45] A successful advertising campaign, including TV advertisements, had led to 300,000 orders, but the Malaysian suppliers were only able to supply 30,000 machines.[citation needed] The apparently strong demand for Electrons proved to be ephemeral: rather than wait, parents bought Commodore 64 or ZX Spectrum for their children's presents. Ferranti solved the production problem and in 1984, production reached its anticipated volumes, but the contracts Acorn had negotiated with its suppliers were not flexible enough to allow volumes to be reduced quickly in this unanticipated situation, and supplies of the Electron built up. At the time of the eventual financial rescue of Acorn in early 1985, it still had 100,000 unsold Electrons plus an inventory of components which had all been paid for and needed to be stored at additional expense.[46] 40,000 BBC Micros also remained unsold.[30]

After a disappointing summer season in 1984, Acorn had evidently focused on making up for lost sales over the Christmas season, with the Electron being a particular focus. However, a refusal to discount the BBC Micro also appeared to inhibit sales of that machine, with some dealers expressing dissatisfaction to the point of considering abandoning the range altogether. With rumours of another, potentially cheaper, machine coming from Acorn,[43] dealers eventually started to discount heavily after Christmas.[47] For instance, high street retailer Rumbelows sought to clear unsold Christmas stocks of around 1500 machines priced at £299, offering a discount of around £100, also bundling them with a cassette recorder and software.[48] The rumoured machine turned out to be the BBC Model B+ which was a relatively conservative upgrade and more, not less, expensive than the machine it replaced.[49] It was speculated that the perception of a more competitive machine soon to be launched might well have kept potential purchasers away from the products that Acorn needed to sell.[50]

Acorn was also spending a large portion of its reserves on development: the BBC Master was being developed; the ARM project was underway; the Acorn Business Computer entailed a lot of development work but delivered few products, with only the 32016-based model ever being sold (as the Cambridge Workstation). The company's research and development staff had grown from around 100 in 1983 to around 150 in 1984, the latter out of a total of 450 employees. Meanwhile, Acorn's chosen method of expansion into West Germany and the United States through the establishment of subsidiaries involved a "major commitment of resources", in contrast with a less costly strategy that might have emphasised collaboration with local distributors. Localisation of the BBC Micro for the US market also involved more expenditure than it otherwise might have due to a failure to consider local market conditions and preferences, with "complex technical efforts" having been made to make the machine compatible with US television standards when local market information would have indicated that "US home computer users expect to use a dedicated personal computer monitor".[30] Consequently, obtaining Federal approval for the BBC Micro in order to expand into the United States proved to be a drawn-out and expensive process that proved futile: all of the expansion devices that were intended to be sold with the BBC Micro had to be tested and radiation emissions had to be reduced. It was claimed that Acorn spent £10 million on its US operation without this localised variant of the BBC Micro establishing a significant market share.[51] The machine, however, did make an appearance in the school of Supergirl in the 1984 film Supergirl: The Movie.[52]

Acorn also made or attempted various acquisitions. The Computer Education in Schools division of ICL was acquired by Acorn in late 1983 "reportedly for less than £100,000", transferring a staff of six to Acorn's Maidenhead office to form Acorn's Educational Services division and to provide "the core of education support development within Acorn".[53] Having had a close relationship with Torch Computers in the early 1980s, Acorn sought to acquire Torch in 1984 with the intention of making Torch "effectively the business arm" of Acorn, despite a lack of clarity about competing product lines and uncertainty about the future of Acorn's still-unreleased business machine within any rationalised product range,[54] although this acquisition was never completed,[55] with Torch having pulled out as Acorn's situation deteriorated.[56]

At around the same time, Acorn also bought into Torus Systems - a company developing a "graphics-controlled local network called Icon" for the IBM PC platform - to broaden Acorn's networking expertise.[57] Icon was a solution based on Ethernet, as opposed to the Acorn-related Econet and Cambridge Ring technologies,[58][59] equipping appropriately specified IBM-compatible computers to participate on a network using a relatively low-cost Ethernet interface card utilising Intel's 82586 network controller chip.[60]: 108 Torus later released a network management solution called Tapestry,[61] based on Icon and marketed by IBM for its own networking technologies.[62] Torus also released support for the use of Novell's Advanced Netware product on its own networking hardware.[63] The company eventually entered receivership in 1990 with Acorn reporting a £242,000 loss associated with the investment.[64] Such were the ambitions of Acorn's management that a joint venture company was established in Hong Kong under the name Optical Information Systems, apparently engaging in the development of "digital, optical technology for computer data storage".[65] Involving a Hong Kong turntable manufacturer, Better Sound Reproduction Ltd., Acorn were to set up a research and development facility in Palo Alto, California, US to bring "compact laser disk drives designed as floppy disk drive replacements" to market within 18 months.[66]: 24

In February 1985, speculation about the state of Acorn's finances intensified with the appointment of a temporary chief executive, Alexander Reid, to run the company, together with the announcement that Acorn had replaced its financial advisors, Lazards, and that the company's stockbrokers, Cazenove, had resigned, ultimately leading to the suspension of Acorn shares, these having fallen to a low of 23 pence per share. With these events reportedly being the result of disagreement between Acorn and Lazards over the measures needed to rescue the company, with Lazards favouring a sale or refinancing whereby the founders would lose control, Acorn and their replacement advisors, Close Brothers, were reported to be pursuing a "radical reorganisation of the company".[55] Lazards had sought to attract financing from GEC but had failed to do so. Close Brothers also found themselves in the position of seeking a financing partner for Acorn, but in a significantly more urgent timeframe, making "financial institutions or a large computer company" the most likely candidates, these having the necessary resources and decision-making agility for a timely intervention.[30]

1985–1998: Olivetti subsidiary

The dire financial situation was brought to a head in February 1985, when one of Acorn's creditors issued a winding-up petition.[67] It would eventually emerge that Acorn owed £31.1 million to various creditors including manufacturers AB Electronics and Wong's Electronics.[68] Wong's had been awarded a $45 million contract to produce the BBC Micro for the US market.[69] During the search for potential financing partners, an Olivetti director had approached Close Brothers, ostensibly as part of Olivetti's strategy of acquiring technologically advanced small companies.[30] After a short period of negotiations, Curry and Hauser signed an agreement with Olivetti on 20 February. With the founders relinquishing control of the company and seeing their combined stake fall from 85.7% to 36.5%, the Italian computer company took a 49.3% stake in Acorn for £10.39 million, which went some way to covering Acorn's £10.9 million losses in the previous six months,[70] effectively valuing Acorn at around a tenth of its valuation of £216 million the year before.[55] Acorn's share price collapse and the suspension of its listing was attributed by some news outlets to the company's failure to establish itself in the US market, with one source citing costs of $5.5 million related to that endeavour.[71]

In July 1985, Olivetti acquired an additional £4 million of Acorn shares, raising its ownership stake in the company to 79.8%. Major creditors agreed to write off £7.9 million in debts, and the BBC agreed to waive 50% of outstanding royalty payments[72] worth a reported £2 million. This second refinancing left the Acorn founders with less than 15% ownership of the company. Meanwhile, the financial difficulties had reduced the number of employees at Acorn from a peak of 480 to around 270.[73]

With Brian Long appointed as managing director, Acorn were set to move forward with a new OEM-focused computer named the Communicator and the Cambridge Workstation, whose launch had been delayed until the end of July 1985 due to the suspension of Acorn's shares. Of subsequent significance, Hermann Hauser was also expected to announce a "VLSI chip design using a reduced instruction set".[73] Unveiled towards the end of 1985,[74] the Communicator was Acorn's answer to ICL's One Per Desk initiative. This Acorn machine was based around a 16-bit 65SC816 CPU, 128 KB RAM, expandable to 512 KB, plus additional battery-backed RAM. It had a new multi-tasking OS, four internal ROM sockets, and shipped with a software suite based on View and ViewSheet. It also had an attached telephone, communications software and auto-answer/auto-dial modem.[75] However, with Acorn's finances having sustained the development cost of the Archimedes, and with the custom systems division having contributed substantially to the company's losses in 1987,[76] a change in strategy took effect towards the end of 1987, moving away from "individual customers" and towards "volume products", resulting in 47 of Acorn's 300 staff being made redundant,[77] the closure of the custom systems division, and the abandonment of the Communicator.[76]

In February 1986, Acorn announced that it was ceasing US sales operations, and sold its remaining US BBC Microcomputers for $1.25 million to a Texas company, Basic, which was a subsidiary of Datum, the Mexican manufacturer of the Spanish version of the BBC Microcomputer (with modified Spanish keyboards for the South American market). The sales office in Woburn, Massachusetts was closed at this time.[78] Acorn was reported as having achieved "negligible U.S. sales".[79] In 1990, in contrast, Acorn set up a sales and marketing operation in Australia and New Zealand by seeking to acquire long-time distributor Barson Computers Australasia, with Acorn managing director Sam Wauchope noting Acorn's presence in Australia since 1983 and being "the only computer manufacturer whose products are recommended by all Australian state education authorities".[80]

Acorn also sought once again to expand into Germany in the 1990s, identifying the market as the largest in Europe whose technically sophisticated computer retailers were looking for opportunities to sell higher-margin products than IBM PC compatibles, with a large enthusiast community amongst existing and potential customers. Efforts were made to establish a local marketing presence and to offer localised versions of Acorn's products.[81] Despite optimistic projections of success, and with Acorn having initially invested £700,000 in the endeavour,[82] the loss-making operation was closed in 1995 as part of broader cost-cutting and restructuring in response to a decline in revenue and difficulties experienced by various Acorn divisions.[83]

Ostensibly facilitated or catalysed by Olivetti's acquisition of Acorn, reports in late 1985 indicated plans for possible collaboration between Acorn, Olivetti and Thomson in the European education sector to define a standard for an educational microcomputer system analogous to the MSX computing architecture and to the established IBM PC compatible architecture.[84] Deliberations continued into 1986, with Acorn proposing its own ARM processor architecture as the basis for the initiative, whereas Thomson had proposed the Motorola 68000.[85] Expectations that Olivetti would actively market Acorn's machines in Europe were, however, frustrated by Olivetti's own assessment of Acorn's products as "too expensive" and the proprietary operating system offering "limited flexibility". Instead, Olivetti sought to promote its M19 personal computer for the European schools market, offering it to Acorn for sale in the UK (ultimately, as the rebadged Acorn M19).[86] Olivetti would eventually offer both Acorn's Master Compact and the Thomson MO6 to the Italian market with its Prodest branding.

Collaboration involving Acorn, Olivetti and Thomson (subsequently as SGS-Thomson) continued in the context of research projects, with a consortium of vendors including AEG, Bull, Philips and ICL participating in the Multiworks initiative to develop Unix workstations as part of the European ESPRIT framework.[87] Acorn's particular role in Multiworks concerned a low-cost workstation featuring the ARM chipset, alongside a "high-cost authoring workstation" based on Olivetti's CP486 workstation.[88] The Chorus system was to be used as the basis of the Unix operating system provided.[89]

Olivetti would eventually relinquish majority control of Acorn in early 1996, selling shares to US and UK investment groups to leave the company with a shareholding in Acorn of around 45%.[90] In July 1996, Olivetti announced that it had sold 14.7% of the group to Lehman Brothers, reducing its stake at that time to 31.2%. Lehman said it planned to resell the shares to investors.[91]

BBC Master and Archimedes

The BBC Master[92] was launched in February 1986 and met with considerable success. From 1986 to 1989, about 200,000 systems were sold,[93] each costing £499, mainly to UK schools and universities. A number of enhanced versions were launched, for example, the Master 512,[94] which had 512 KB of RAM and an internal 80186 processor for MS-DOS compatibility, and the Master Turbo,[95] which had a 65C102 second processor.

The first commercial use of the ARM architecture was in the ARM Development System, a Tube-linked second processor for the BBC Master which allowed one to write programs for the new system. It sold for £4,500 and included the ARM processor, 4 MB of RAM and a set of development tools with an enhanced version of BBC BASIC. This system did not include the three support chips (VIDC, MEMC, and IOC) which were later to form part of the Archimedes system. They made their first appearance in the A500 second processor,[96] which was used internally within Acorn as a development platform, and had a similar form-factor to the ARM development system.

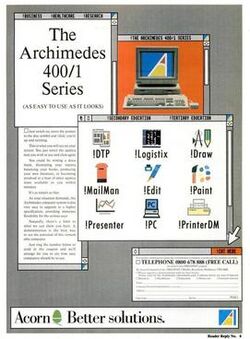

The second ARM-based product was the Acorn Archimedes desktop-computer, released in mid-1987, some 18 months after IBM launched their RISC-based RT PC.[97] The first RISC-based home computer, using the ARM (Acorn RISC Machine) chip,[98] the Archimedes was popular in the United Kingdom , Australasia and Ireland, and was considerably more powerful and advanced than most offerings of the day. The Archimedes was advertised in both printed[99] and broadcast media.[100] One example of such advertising is a mock-up of the RISC OS 2 desktop, showing some software application directories, with the advert text added within windows.[101] However, the vast majority of home users opted for an Atari ST or Amiga when looking to upgrade their 8-bit micros. As with the BBC, the Archimedes instead flourished in schools and other educational settings but just a few years later in the early 1990s this market began stratifying into the PC-dominated world. Acorn continued to produce updated models of the Archimedes, including a laptop (the A4), and in 1994 launched the Risc PC, whose top specification would later include a 233 MHz StrongARM processor. These were sold mainly into education, specialist and enthusiast markets, such as professional composers using Sibelius 7.

ARM Ltd.

Acorn's silicon partner, VLSI, had been given the task of finding new applications for the ARM CPU and support chips. Hauser's Active Book company had been developing a handheld device and for this the ARM CPU developers had created a static version of their processor, the ARM2aS.

Members of Apple's Advanced Technology Group (ATG) had made initial contact with Acorn over use of the ARM in an experimental Apple II (2) style prototype called Möbius. Experiments done in the Möbius project proved that the ARM RISC architecture could be highly attractive for certain types of future products. The Möbius project was briefly considered as the basis for a new line of Apple computers but it was stopped for fear it would compete with the Macintosh and confuse the market. However, the Möbius project evolved awareness of the ARM processor within Apple. The Möbius Team made minor changes to the ARM registers, and used their working prototype to demonstrate a variety of impressive performance benchmarks.[102]

Later Apple was developing an entirely new computing platform for its Newton. Various requirements had been set for the processor in terms of power consumption, cost and performance, and there was also a need for fully static operation in which the clock could be stopped at any time. Only the Acorn RISC Machine came close to meeting all these demands, but there were still deficiencies. The ARM did not, for example, have an integral memory management unit, as this function was being provided by the MEMC support chip and Acorn did not have the resources to develop one.[103]

Apple and Acorn began to collaborate on developing the ARM, and it was decided that this would be best achieved by a separate company.[103] The bulk of the Advanced Research and Development section of Acorn that had developed the ARM CPU formed the basis of ARM Holdings when that company was spun off in November 1990. Acorn Group and Apple Computer Inc. each had a 43% shareholding in ARM (in 1996),[104] while VLSI was an investor and first ARM licensee.[105]

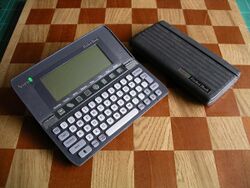

Acorn Pocket Book

In 1993, Acorn decided to offer an Acorn branded Psion Series 3 PDA, badged as an Acorn Pocket Book, with a later variant branded the Acorn Pocket Book II. Essentially a rebadged OEM version of the Series 3 with slightly different on-board software, the device was marketed as an inexpensive computer for schoolchildren, rather than as an executive tool.[106] The hardware was the same as the Series 3, but the integrated applications were different. For instance, the Pocket Book omitted the Agenda diary and Spell dictionary applications, which became an optional application, supplied on ROM SSD which could be inserted into either of the ROM bays underneath the device. Other programs were renamed: System became Desktop, Word became Write, Sheet became Abacus and Data became Cards.[107][108]

Set-top boxes

In 1994, Acorn established a new division, Online Media, focusing on interactive multimedia client hardware.[109] Online Media aimed to exploit the projected video-on-demand (VOD) boom, an interactive television system which would allow users to select and watch video content over a network.[110] In September 1994 the Cambridge Digital Interactive Television Trial of video-on-demand services was set up by Online Media, Anglia Television, Cambridge Cable (now part of Virgin Media) and Advanced Telecommunication Modules Ltd (ATML). The trial involved creating a wide area ATM network linking TV-company to subscribers' homes and delivering services such as home shopping, online education, software downloaded on-demand and the World Wide Web. The wide area network used a combination of fibre and coaxial cable, and the switches were housed in the roadside cabinets of Cambridge Cable's existing network.[111] Olivetti Research Laboratory developed the technology used by the trial. An ICL video server provided the service via ATM switches manufactured by ATML, another company set up by Hauser and Hopper. The trial commenced at a speed of 2 Mbit/s to the home, subsequently increased to 25 Mbit/s.[112]

Subscribers used Acorn Online Media Set Top Boxes. For the first six months the trial involved 10 VOD terminals;[112] the second phase was expanded to cover 100 homes and eight schools with a further 150 terminals in test labs. A number of other organisations gradually joined in, including the National Westminster Bank (NatWest), the BBC, the Post Office, Tesco, and the local education authority.[which?] Having initially deployed set-top boxes based on Risc PC hardware, a second generation of the hardware, STB2, featured the ARM7500 system-on-a-chip,[113] this having been manufactured for Online Media by VLSI,[114] and integrated MPEG video decoding hardware. (The C-Cube Microsystems CL450 part is evident on the STB20 circuit board,[115] this product being an MPEG-1 decoder introduced in May 1992.[116]) Plans were announced to expand the initiative from 250 homes to 1000, to support NatWest's cable television banking and shopping services, with video on demand provision being strengthened through the deployment of a digital video server from ICL having "a maximum capacity of several hundred gigabytes of fast hard disc storage", connected via a 155 Mbit/s link and supplementing Olivetti Research Disc Bricks already acting as smaller capacity video servers. Industry support for the Online Media platform was also announced by Oracle and Macromedia.[113]

BBC Education tested delivery of radio-on-demand programmes to primary schools, and a new educational service, Education Online, was established to deliver material such as Open University television programmes and educational software. Netherhall School was provided with an inexpensive video server and operated as a provider of trial services, with Anglia Polytechnic University taking up a similar role some time later.[111]

It was hoped that Online Media could be floated as a separate company, and a share issue raising £17.2 million of additional capital was announced in 1995,[117] this to finance the division and "underpin Acorn Group finances" against a backdrop of deteriorating financial results partly caused by an increasingly uncompetitive lower-end product range.[118] Having entered into a deal with Lightspan Partnership Inc. to supply set-top boxes for the US education market,[119] the order was cancelled and put pressure on Acorn's already straitened financial situation. Various other factors ensured that the predicted video-on-demand boom never really materialised as anticipated.[120]

Acorn subsequently planned to incorporate set-top box technology into its product range, launching an initiative entitled "No Limits to Learning" and previewing a range of products under the MediaRange brand, with the MediaSurfer being "essentially an Online Media STB with a World Wide Web browser built in", and with other products in the range being based on "focused applications" of established Acorn products.[121] Evolution of the technology continued with the launch of the STB22 model, described as "a cross between an NC (Network Computer) and a STB". This model combined set-top box features such as ATM25 networking for interactive video with more general Internet features such as Web browsing and Java application support. Described as "the icing on the cake", MPEG2 video decoding hardware was provided by a chipset from LSI. Although Acorn were reportedly hoping for the interactive television market to "eventually take off" and initiate "mass deployment" by traditional telecoms operators, corporate intranet applications were also seen as a target market. With more conservative deployments in mind, the ATM25 interface in the product could be replaced by an Ethernet interface.[122]

NewsPad

In 1994, the EU initiated the NewsPad[123] programme, with the aim of developing a common mechanism to author and deliver news electronically to consumer devices. The programme's name and format were inspired by the devices described and depicted in Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick's 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Acorn won a contract to develop a consumer device / receiver, and duly supplied a RISC OS-based touch-screen tablet computer for the pilot.[124][125][126] The device measured 8.5 × 11 inches (220 × 280 mm) and was being tried in 1996 in Spain by Ediciones Primera Plana.[127] The Barcelona-based pilot ended in 1997, but the tablet format and ARM architecture may have influenced Intel's 1999 WebPad / Web Tablet program.[128][129][130]

SchoolServer

Although Acorn had largely focused on its ARM-based product range offering RISC OS (and, for a time, RISC iX), albeit with an increasing emphasis on DOS and Windows compatibility through its PC card products,[131][132] the emergence of larger networks in education connecting systems based on different computing platforms—typically Acorn, PC and Apple Macintosh—motivated the introduction of the SchoolServer product range in 1995. The range consisted of server systems manufactured by IBM running Windows NT Server (specifically Windows NT 3.5[119]), employing a single 100 MHz PowerPC processor, with 24 MB or 32 MB of RAM, one or two 1 GB hard drives, and built-in Ethernet interfaces.[133]

Acorn bundled ANT Limited's OmniClient software to provide the connectivity support required for Acorn's own computers to access the SchoolServer's facilities, these being based on Microsoft's own SchoolServer platform and proprietary networking technologies. The adoption of such hardware and software platforms, motivated by concerns about the capabilities of Acorn's existing products (such as the Risc PC) in the server role, even apparently led to Acorn becoming a Microsoft Solution Provider despite having been "very vocal critics" of Microsoft and its technologies in the past.[119]

Other companies in the educational market introduced similar products to the SchoolServer. For instance, Datathorn Systems introduced a solution called Super Server based on the Motorola PowerStack server system,[134] which was a PowerPC-based machine capable of running Windows NT 3.51 or AIX 4.1,[135] with the Super Server project reportedly being "the product of research at both Oxford and Cambridge universities". Having approval from Acorn and offering interoperability between Acorn and PC platforms, the solution was deployed at several sites.[136]

Xemplar Education

In 1996, Acorn entered into a joint venture with Apple Computer UK called Xemplar to provide computers and services to the UK education market.[137] Described as "the unthinkable" and a "marriage of convenience", the alliance sought to reverse the declining fortunes of both Acorn and Apple in the sector, also prompting speculation that Apple's own strategy based on adoption of the PowerPC platform might lead Acorn along the same path, with Acorn already having expressed some interest in PowerPC and having introduced a PowerPC-based product in the form of its SchoolServer offering. The deal was regarded as benefiting Apple more strongly, with Acorn developers being encouraged to port their software to Mac OS, and with RISC OS effectively being sidelined to Acorn's set-top box and network computing products.[138]

Xemplar initially resisted the demand for PC-compatible products in classrooms, limiting its PC offerings to school administration.[139] A survey in 1998 found that Apple and Acorn systems at that time accounted for 47% and 1⁄3 of computers in UK primary and secondary schools respectively.[140] However, in 1999, with Acorn undergoing restructuring, the company's remaining stake in Xemplar was sold to Apple for £3 million.[141][142] By this time, Xemplar had become "a significant supplier of Wintel PCs" out of commercial necessity, with Acorn's Network Computer being the only product from its former co-owner still actively marketed by Xemplar.[141] Despite Acorn's own upheavals, Xemplar remained committed to selling Acorn products in its portfolio.[143] Renamed to Apple Xemplar Education, the operation was wound up in 2014.[144] Acorn Education and later Xemplar Education were heavily involved in Tesco's "Computers for Schools" programme in the UK, providing hardware and software in exchange for vouchers collected from Tesco purchases.[145]

The Welsh Office Multimedia/Portables Initiative (WOMPI), launched in 1996 to provide primary schools with computer equipment,[146] prescribed that Welsh schools choosing the multimedia option received multimedia PCs exclusively supplied by RM. This upset other suppliers such as Xemplar and members of the National Association of Advisers for Computers in Education (NAACE), with complaints including those about the imposition of an incompatible computing platform on small schools who were already committed to the RISC OS platform, these schools being potentially incapable of managing "a mix of machines", and the lack of appropriate Welsh language software for the Windows platform, this being of particular concern in schools where lessons were "conducted exclusively in Welsh" and where an "excellent working relationship with British software houses" had cultivated the availability of major RISC OS applications in Welsh. The range of multimedia software offered in the initiative was also criticised: "none of the scheme's CD-Roms" were in Welsh, and Acorn machines also needed additional software, at an estimated £300 in extra costs, to "make effective use" of the software titles.[147]

Network computers

This article appears to contradict the article Acorn Network Computer. (July 2011) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

When BBC2's The Money Programme screened an interview with Larry Ellison in October 1995, Acorn Online Media Managing Director Malcolm Bird realised that Ellison's network computer was, basically, an Acorn set-top box.[148] After initial discussions between Oracle Corporation and Olivetti, Hauser and Acorn a few weeks later, Bird was dispatched to San Francisco with Acorn's latest Set Top Box. Oracle had already talked seriously with computer manufacturers including Sun and Apple about the contract for putting together the NC blueprint machine; there were also rumours in the industry that said Oracle itself was working on the reference design. After Bird's visit to Oracle, Ellison visited Acorn and a deal was reached: Acorn would define the NC Reference Standard.

Ellison was expecting to announce the NC in February 1996. Sophie Wilson was put in charge of the NC project, and by mid-November a draft NC specification was ready. By January 1996 the formal details of the contract between Acorn and Oracle had been worked out,[149] and the PCB was designed and ready to be put into production.[148] In February 1996, Acorn Network Computing was founded.[104] In August 1996 it launched the Acorn Network Computer.

It was hoped that the Network Computer would create a significant new sector in which Acorn Network Computing would be a major player,[150] either selling its own products or earning money from licence fees paid by other manufacturers for the right to produce their own NCs. To that end, two of Acorn's major projects were the creation of a new 'consumer device' operating system named Galileo, and, in conjunction with Digital Semiconductor and ARM, a new StrongARM chipset consisting of the SA-1500 and SA-1501. Galileo's main feature was a guarantee of a certain quality of service to each process in which the resources (CPU, memory, etc.) required to ensure reliable operation would be kept available regardless of the behaviour of other processes.[151] The SA-1500 sported higher clock rates than existing StrongARM CPUs and, more importantly, a media-focussed coprocessor (the Attached Media Processor or AMP). The SA-1500 was to be the first release target for Galileo.[152]

After having incorporated its STB and NC business areas as separate companies, Acorn created a new wholly owned subsidiary, Acorn RISC Technologies (ART). ART focused on the development of other software and hardware technologies built on top of ARM processors.[104]

1998–1999: Element 14 and MSDW acquisition

During the first half of 1998 Acorn's management were heavily involved in the initial public offering of ARM Holdings plc which raised £18 million for Acorn throughout 1998.[153] In June 1998, Stan Boland took over as CEO of Acorn Computers from David Lee,[154] initiating a review of Acorn's core business.[153]

The company had losses of £9 million in the first nine months of the year[153] and in September 1998 the results of the review led to a significant restructuring of the company.[155] The Workstation division was to close,[156] a 40% reduction in staff, and the Risc PC 2 code-named Phoebe that was nearing completion was cancelled.[157] These actions allowed the company to reduce ongoing losses and focus on other activities.[153][158] Acorn concentrated on development of digital TV set-top boxes and high performance media centric DSP (silicon and software). It also produced a reference design for a Windows NT thin client using a Cirrus Logic system on a chip.[159][160][161]

Refocusing and discontinuation of activities

To concentrate on these two activities Acorn hired a group of former STMicroelectronics silicon-design engineers and they formed the basis of a £2 million silicon-design centre that Acorn set up in Bristol.[153][162] They also started to dispose of some of their interests in the former workstation market and in January 1999 sold their 50% interest in Xemplar Education to Apple Computer.[163][164]

Attempts were made to secure the rights to Acorn's desktop products including network computers and "various associated technologies", RISC OS, and the abandoned Phoebe workstation project by a consortium of Acorn market interests, and a memorandum of understanding was reportedly signed by both Stan Boland, representing Acorn, and former Acorn executive Peter Bondar, representing the consortium. However, Acorn pulled out of this tentative deal amidst accusations of attempts to sideline the consortium and to negotiate directly with its financial backers.[165] It was reported that Stephen Streater of Eidos may have made a £0.5 million bid for the rights to the PC range,[8] but in October 1998 the distribution rights to the existing designs of machines were granted to Castle Technology to supply Acorn's dealer network.[158][166][167] In March 1999, RISCOS Ltd acquired a licence to develop and release RISC OS.[168][169]

Chief Executive, Stan Boland, in September 1998[170]

By January 1999, Acorn Computers Limited had renamed to Element 14 Limited (though still owned by Acorn Group plc), referring to the element silicon with atomic number 14; this change was to reflect the changed nature of the business and to distance itself from the education market that Acorn Computers was most known for.[158][171] Other names had been considered by the company, but the domain name e-14.com had been registered before the official announcement.[172]

Acquisition and asset disposal

Ultimately, the widely anticipated issues around releasing Acorn's 24% shareholding in ARM, with a need for "minimising the massive tax burden posed by disposing the holding",[173] were resolved through "creative accounting courtesy of Morgan Stanley", with an offshore subsidiary of the bank acquiring Acorn, releasing the £300 million shareholding "using the purchase as a tax loss and swapping Acorn investors' shares for ARM shares", and with the bank retaining an estimated £40 million shareholding in ARM as a consequence.[174] As part of the process leading to the acquisition of Acorn by the Morgan Stanley subsidiary, MSDW Investment Holdings Limited, with the intention to "minimise the liabilities" of the group through the disposal of assets, Pace Micro Technology agreed to acquire Acorn's set-top box division for approximately £200,000,[153] also obtaining Acorn's rights and obligations with regard to RISC OS.[175]

In conjunction with the acquisition of Acorn, an offer was extended to a company "owned by Stan Boland and certain senior management to purchase ... the silicon and software design activity" for approximately £1 million. This distinct company (known as "New Jam Inc"[176]) effectively became the independent Element 14 venture,[153] acquiring the name from the former Acorn Computers Limited which then became known as Cabot 2 Limited.[177] A subsequent report put the sale price of this division of Acorn at £1.5 million, offering the prescient observation that this new business would itself be acquired for "several million pounds" by an established company in the industry.[175] This anticipated acquisition, involving Broadcom, occurred the following year.[178]

1999–2015: Legacy operations

Acorn Computers, in its new guise of Cabot 2, would continue to administer the remaining assets of the business and to "tidy up remaining contractual and logistical obligations", these including the servicing of product warranties. In late 1999, Reflex Electronics signed a five-year contract to perform warranty work and technical support for Acorn-manufactured products, renewing an earlier arrangement with Acorn.[179] Acorn Group – the parent company of Acorn Computers Limited – had itself been renamed from Acorn Computer Group in 1997, and the company was subsequently renamed Cabot 1 Limited and taken private by MSDW in February 2000.[180] The company remained active until being dissolved in December 2015.[181]

Legacy

The legacy[182] of the company's work is evidenced in spin-off technologies, with the company being described in 2013 as "the most influential business in the innovation cluster's history".[183]

Revival of the Acorn trademark

In early 2006, the dormant Acorn trademark was licensed from the France company Aristide & Co Antiquaire de Marques, by a new company based in Nottingham.[184] This company was dissolved in late 2009.

On 23 February 2018 the Acorn trademark made another return when a new company Acorn Inc. Ltd announced a brand new smartphone, the Acorn Micro C5.[185] The Acorn Micro C5 has since been discontinued.

Popular culture

In 2009, BBC4 screened Micro Men, a drama based on the rivalry between Acorn Computers and Sinclair's competing machines.[186]

TV series

Acorn products featured prominently in a number of Educational television series, including:

- The Computer Programme

- Micro Live

- Making the Most of the Micro

- Computers in Control[citation needed]

Magazines

Acorn products spawned a series of dedicated publications, including:

- Acorn User (named BBC Acorn User while its publisher was owned by the BBC)

- The Micro User (initially BBC Micro User, renamed due to a trade mark objection) / Acorn Computing

- Archive

- BEEBUG / Risc User

- Archimedes World

- Electron User

- A&B Computing

They also featured in dedicated sections of:

- Computer Shopper

- Personal Computer News

- Personal Computer World

- Computer Gamer

- Home Computing Weekly

- rem

See also

- Acornsoft

- Amber (processor core)

- Arm

- List of Acorn Electron games

- List of British computers

- Microelectronics Education Programme

- Olivetti

- RISC OS

Notes

- ↑ "History of ARM: from Acorn to Apple". 6 January 2011. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/epic/arm/8243162/History-of-ARM-from-Acorn-to-Apple.html.

- ↑ "ARM CPU Core Dominates Mobile Market". Tech-On!. Nikkei Electronics Asia. http://techon.nikkeibp.co.jp/NEA/archive/200204/177680/.

- ↑ "Acorn founder advocates moving datacentres to NZ". Stuff.co.nz. 31 January 2009. http://www.stuff.co.nz/technology/it-telcos/809498/Acorn-founder-advocates-moving-datacentres-to-NZ. "Acorn Computers, once regarded as the UK's equivalent of Apple Computer ..."

- ↑ Report on Network Computer Technology . Simon Booth, European Commission, 1999.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Shillingford, Joia (2001-03-08). "From the BBC Micro, little Acorns grew". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2001/mar/08/onlinesupplement5. "Originally, Acorn planned to use Intel's 286 chip in its Archi-medes computer. But because Intel would not let it license the 286 core and adapt it, Acorn decided to design its own."

- ↑ Athreye, Suma S. (18 July 2000). "Agglomeration and Growth: A Study of the Cambridge Hi-Tech Cluster". SIEPR Discussion Paper No. 00-42. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. http://www-siepr.stanford.edu/papers/pdf/00-42.pdf.

- ↑ Meyer, David (19 November 2010). "Dead IT giants: A top 10 of the fallen". ZDNet. http://www.zdnet.com/pictures/dead-it-giants-a-top-10-of-the-fallen/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Great oaks from little Acorns? No". Personal Computer World. 26 November 1998. http://www.computeractive.co.uk/pcw/news/1924362/great-oaks-little-acorns-no.

- ↑ Adamson, Ian; Kennedy, Richard (1986). Sinclair and the Sunrise Technology: The Deconstruction of a Myth (1st ed.). Harmondsworth, England: Penguin Books LTD. pp. 262. ISBN 978-0-14-008774-1.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Sethi, Anand (2008-04-15). "UK electronics – a fallen or sleeping giant?". EMT WorldWide. IML Group. http://www.emtworldwide.com/article/14402/UK-electronics-a-fallen-or-sleeping-giant-.aspx. "One of Sir Clive's long term employees, Chris Curry quit because of differences over the technology roadmap [...] Finding nothing readily available on the market including from the leading US chip manufacturers [...] RISC processor called ARM which basically had the design ethos of the simple 6502 but in a 32 bit RISC environment making it that much simpler to fabricate and test."

- ↑ Garnsey, Elizabeth; Lorenzoni, Gianni; Ferriani, Simone (2008). "Speciation through entrepreneurial spin-off: The Acorn-ARM story". Research Policy 37 (2): 210–224. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2007.11.006. http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/19249/1/Speciation%20through%20Entrepreneurial%20Spin-off.pdf.

- ↑ "News - Business Weekly - Technology News - Business news - Cambridge and the East of England". http://www.businessweekly.co.uk/news/cambridge-torchbearers/arm-and-man-hauser%E2%80%99s-list-legacy-stands-test-time%7Cdate=July.

- ↑ "Acorn System 1 price list". http://www.speleotrove.com/acorn/acornPriceList.gif.

- ↑ Whytehead, Chris. "Acorn System 2". The Centre for Computing History. https://chrisacorns.computinghistory.org.uk/Computers/System2.html.

- ↑ Whytehead, Chris. "Acorn System 3". The Centre for Computing History. https://chrisacorns.computinghistory.org.uk/Computers/System3.html.

- ↑ Whytehead, Chris. "Acorn System 4". The Centre for Computing History. https://chrisacorns.computinghistory.org.uk/Computers/System4.html.

- ↑ Whytehead, Chris. "Acorn System 5". The Centre for Computing History. http://acorn.chriswhy.co.uk/Computers/System5.html.

- ↑ Attack, Carol (October–December 1988). "From Atom to Arc". Acorn User. "Should Acorn abandon the 6502 processor which lay at the heart of all its machines? Should the next machine be full of the latest features or should it sacrifice advanced technology for the mass market?".

- ↑ Kibble-White, Jack (December 2005). "Standby for a Data-Blast". http://www.offthetelly.co.uk/?page_id=568.

- ↑ Langley, Nick (1989-09-09). "Schools: the early learning curve". New Scientist: pp. 65. "In 1981 the British government launched a scheme which offered schools 50% of the cost of a computer from one of three suppliers. The computers were the Sinclair Spectrum, the BBC Micro from Acorn and the Research Machines 380Z, all 8-bit machines."

- ↑ Sadauskas, Andrew (27 July 2012). "BBC Micro B lives on: Strong growth for ARM after increased tablet and smartphone use". SmartCompany. http://www.smartcompany.com.au/information-technology/050914-bbc-micro-b-lives-on-strong-growth-for-arm-after-increased-tablet-and-smartphone-use.html.

- ↑ "BBC Micro ignites memories of revolution". BBC News. 2008-03-21. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/technology/7307636.stm.

- ↑ "Acorn celebs to mark 30th anniversary with reunion". 2008-01-28. http://www.drobe.co.uk/riscos/artifact2200.html. "Top Acorn Computers luminaries are planning a reunion for former company staff to mark the firm's 30th birthday, drobe.co.uk has learned."

- ↑ Smith, Tony (2008-08-28). "Acorn alumni to toast tech pioneer's 30th anniversary". RegHardware, The Register. http://www.reghardware.com/2008/08/28/acorn_30_reunion/. "Some 400 staffers from that flag bearer of the 1980s UK home computing revolution, Acorn, are to gather next month to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the firm's foundation."

- ↑ Goodwins, Rupert; Barker, Colin (2008-08-29). "Acorn to celebrate 30th anniversary". ZDNet. http://www.zdnet.co.uk/news/desktop-hardware/2008/08/29/acorn-to-celebrate-30th-anniversary-39472541/. "Thirteenth of September will see the 30th anniversary of UK technology company Acorn Computers, famous in the 1980s 8-bit boom for its 6502-based microcomputers such as the Electron, Atom and BBC Micro. Some 400 previous employees and guests are expected at a celebratory party, which will be held in the grounds of Cherry Hinton Hall, Cambridge, close to the company's old HQ."

- ↑ "Mighty Acorn holding 30th anniversary reunion bash". Business Weekly. 2008-08-28. http://www.businessweekly.co.uk/hi-tech/10127-mighty-acorn-holding-30th-anniversary-reunion-bash?date=2011-02-01. "Around 400 ex-Acorn employees and guests are expected to attend the event in Cambridge on September 13th. It will be held in the grounds of Cherry Hinton Hall, close to the company's old headquarters building."

- ↑ "Editorial". Popular Computer Weekly: pp. 3. 6 October 1983. https://archive.org/details/popular-computing-weekly-1983-10-06/page/n2/mode/1up.

- ↑ "October 6 1983 - Electronics Times - Find Articles". 11 July 2012. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0WVI/is_1998_Oct_5/ai_59214055/.

- ↑ Acorn Computer Group PLC. Macmillan Publishers Ltd. 1990. pp. 139. ISBN 978-1-349-11287-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=rCqwCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA139. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Fleck, Vivien; Garnsey, Elizabeth (1 March 1988). "Managing Growth at Acorn Computers". Journal of General Management 13 (3): 4–23. doi:10.1177/030630708801300301. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/030630708801300301. Retrieved 19 June 2021.

- ↑ This is Acorn Computer. Acorn Computers Limited. pp. 36. http://www.computinghistory.org.uk/userdata/files/this_is_acorn_computer.pdf. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ↑ Whytehead, Chris (2 May 2014). "Acorn 6809 CPU". http://chrisacorns.computinghistory.org.uk/8bit_Upgrades/Acorn_6809_CPU.html.

- ↑ "IBM's Invention of the First Personal Computer". http://inventors.about.com/library/weekly/aa031599.htm.

- ↑ "Acorn re-enters the marketplace". New Scientist: pp. 32. 1985-08-08. "Acorn [...] unveiled two products last week – a cheap microprocessor chip and a range of scientific workstations. [...] called the Acorn Cambridge Workstation, was developed from Acorn's now defunct range of business micros and is compatible with the BBC Micro."

- ↑ Acorn Cambridge Workstation, New Scientist, 1986-04-24, https://books.google.com/books?id=_7sirll_RDUC&q=acorn+computers+%22choice+of+experience%22+-chriswhy.co.uk+-wikipedia.org&pg=PA48, retrieved 2011-10-17, "Happily, all the mainframe power you have been waiting for can now be found in a 32-bit micro – the Acorn Cambridge Workstation."[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Chisnall, David (2010-08-23). "Understanding ARM Architectures". http://www.informit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=1620207.

- ↑ Furber, Stephen B. (2000). ARM system-on-chip architecture. Boston: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-67519-6.

- ↑ Hammond, Ray (1987-06-18). "'Fastest' micro in the world". New Scientist: pp. 41. "Acorn first started working on its RISC research programme in 1983. [...] has spent £5 million developing the RISC microprocessor [...]"

- ↑ Garnsey, Elizabeth; Lorenzoni, Gianni; Ferriani, Simone (March 2008). "Speciation through entrepreneurial spin-off: The Acorn-ARM story". Research Policy 37 (2): 210–224. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2007.11.006. http://www2.sa.unibo.it/~simone.ferriani/Download/Speciation%20through%20Entrepreneurial%20Spin-off.pdf. Retrieved 2011-06-02. "[...] the first silicon was run on April 26th 1985.".

- ↑ Acorn Risc technology, New Scientist, 1986-07-31, https://books.google.com/books?id=WUO69PwV1vgC&q=new+scientist+acorn+risc&pg=PA40, retrieved 2011-05-26[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "High hopes for Advanced Risc Machines Ltd as Acorn returns to the black". Computergram International (Computer Business Review). 26 April 1992. http://www.cbronline.com/news/high_hopes_for_advanced_risc_machines_ltd_as_acorn_returns_to_the_black.

- ↑ Hansen, Martin (2004-03-01). "Castle, RISCOS Ltd., FinnyBank theatre report". Drobe. http://www.drobe.co.uk/article.php?id=990. "In Acorn's prime, 200 people worked on developing the OS [...]"

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Kewney, Guy (March 1985). "Unfinished business". Personal Computer World: pp. 94, 99. https://archive.org/details/PersonalComputerWorld1985-03/page/94/mode/1up.

- ↑ Sanger, David E. (3 July 1984). "Warner Sells Atari To Tramiel". The New York Times: pp. Late City Final Edition, Section D, Page 1, Column 6, 1115 words. http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F30B10FF395D0C708CDDAE0894DC484D81&scp=2&sq=atari+tramiel+240&st=nyt.

- ↑ Chris's Acorns Acorn Electron - Release and ULA supply issues.

- ↑ "Beeb safe, but ABCs under review". Acorn User: pp. 7. April 1985. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser033-Apr85/page/n8/mode/1up.

- ↑ Kewney, Guy (April 1985). "Acorn reprise". Personal Computer World: pp. 106–107. https://archive.org/details/PersonalComputerWorld1985-04/page/106/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Cut price BBC B's". Popular Computing Weekly: pp. 10. 28 February 1985. https://archive.org/details/popular-computing-weekly-1985-02-28/page/n9/mode/1up.

- ↑ Kewney, Guy (June 1985). "Acorn anti-climax". Personal Computer World: pp. 124. https://archive.org/details/PersonalComputerWorld1985-06/page/124/mode/1up.

- ↑ Kewney, Guy (July 1985). "Newsprint". Personal Computer World: pp. 111. https://archive.org/details/PersonalComputerWorld1985-07/page/111/mode/1up.

- ↑ Littler, Gareth (May 1985). "Amstrad Education Campaign". Amstrad Computer User: 98–99. https://archive.org/details/AmstradComputerUser06-0585/page/n97/mode/2up. Retrieved 13 February 2023.

- ↑ "Starring the Computer - Supergirl". http://www.starringthecomputer.com/feature.php?f=396.

- ↑ "Acorn shot in the arm". Popular Computing Weekly: pp. 1. 17 November 1983. https://archive.org/details/popular-computing-weekly-1983-11-17/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Acorn acquires Torch". Acorn User: pp. 7. June 1984. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser023-Jun84/page/n8/mode/1up.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 "Black week for Acorn". Popular Computing Weekly: pp. 1. 14 February 1985. https://archive.org/details/popular-computing-weekly-1985-02-14.

- ↑ "Acorn searches for way out of crisis". Personal Computer News: pp. 1. 16 February 1985. https://archive.org/details/personal-computer-news-099/page/n1/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Acorn's Icon". Acorn User: pp. 7. June 1984. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser023-Jun84/page/n8/mode/1up.

- ↑ Kewney, Guy (August 1988). "Newsprint". Personal Computer World: pp. 94. https://archive.org/details/PersonalComputerWorld1984-08/page/94/mode/1up.

- ↑ Jones, Keith (November 1984). "Britain's Torus Systems employs icons to help IBM PC users on local networks". Mini-Micro Systems: 83–84,86. https://archive.org/details/bitsavers_MiniMicroS_172417378/page/83/mode/1up. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ↑ "British Information Services Advertising Supplement". Micro Marketworld: 104–109. 12 November 1984. https://archive.org/details/sim_micro-marketworld_1984-11-12_7_22/page/107/mode/1up. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ↑ Kewney, Guy (May 1985). "Newsprint". Personal Computer World: pp. 117. https://archive.org/details/PersonalComputerWorld1985-05/page/117/mode/1up.

- ↑ Jones, Russell (May 1986). "Networking made simpler". Data Processing: 199–203. https://archive.org/details/sim_data-processing_1986-05_28_4/page/n32/mode/1up. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ↑ "Third party networking". Data Processing: 444. October 1986. https://archive.org/details/sim_data-processing_1986-10_28_8/page/n57/mode/1up. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ↑ "Hard Times". Acorn User: pp. 7. December 1990. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser101-Dec90/page/n8/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Supershorts". Computerworld: 118. 21 May 1984. https://archive.org/details/computerworld1821unse/page/118/mode/1up. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- ↑ "Breakpoints". Mini-Micro Systems: 15–16,19–20,23–24. July 1984. https://archive.org/details/bitsavers_MiniMicroS_183091910/page/24/mode/1up. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ↑ "Troubled Acorn faces winding-up order". Popular Computing Weekly: pp. 1. 21 February 1985. https://archive.org/details/popular-computing-weekly-1985-02-21.

- ↑ "Acorn's shares re-open on USM". Popular Computing Weekly: pp. 4. 14 March 1985. https://archive.org/details/popular-computing-weekly-1985-03-14/page/n3/mode/1up.

- ↑ "BBC Micro news". Practical Computing: 15. November 1983. https://worldradiohistory.com/UK/Practical-Computing/80s/Practical-Computing-1983-11-S-OCR.pdf. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ↑ "Electron in doubt after rescue". Popular Computing Weekly: pp. 1, 4. 28 February 1985. https://archive.org/details/popular-computing-weekly-1985-02-28/mode/1up.

- ↑ "International Report". Computerworld: pp. 38. 25 February 1985. https://archive.org/details/computerworld198unse/page/n37/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Olivetti cash revives Acorn". Home Computing Weekly: pp. 1. 30 July 1985. https://archive.org/details/home-computing-weekly-123.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 "The saving of Acorn - part 2". Acorn User: pp. 7. September 1985. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser038-Sep85/page/n8/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Communicator's wide appeal". Acorn User: pp. 11. December 1985. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser041-Dec85/page/n12/mode/1up.

- ↑ Whytehead, Chris. "Communicator". The Centre for Computing History. http://chrisacorns.computinghistory.org.uk/Computers/Communicator.html.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "Optimism reigns despite '87 losses". Acorn User: pp. 9. June 1988. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser071-Jun88/page/n10/mode/1up. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ↑ "Acorn staff sacked". Popular Computing Weekly: pp. 4. 17 December 1987. https://archive.org/details/NH2021_Popular_Computing_Weekly_Issue871217.pdf/page/n3/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Acorn moves out of US". Acorn User: pp. 9. February 1986. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser043-Feb86/page/n10/mode/1up.

- ↑ Warner, Edward (30 June 1986). "Centralized decision making hurts foreign firms in U.S. mart". Computerworld: pp. 118, 94. https://archive.org/details/computerworld2026unse/page/118/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Acorn Enters the Land of Oz". Acorn User: pp. 7. July 1990. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser096-Jul90/page/n8/mode/1up.

- ↑ Ensor, Philip (May 1994). "Acorn in Germany". Acorn User: pp. 69–71. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser142-May94/page/n68/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Financial stakes". Acorn User: pp. 11. August 1994. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser145-Aug94/page/n10/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Acorn's balance sheet". Acorn User: pp. 10. May 1996. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser168-May96/page/n9/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Big three go for European micro". Acorn User: pp. 7. November 1985. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser040-Nov85/page/n8/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Acorn RISCs it on micro standard". Acorn User: pp. 7. April 1986. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser045-Apr86/page/n8/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Herman Hauser moves to top Olivetti post". Your Computer: pp. 11. April 1986. https://archive.org/details/Your_Computer_Magazine_Issue_V604/page/11/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Acorn works on Unix for Europe". Acorn User: pp. 7. December 1988. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser077-Dec88/page/n8/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Multimedia Integrated Workstations". December 1993. http://research.cs.ncl.ac.uk/cabernet/www.laas.research.ec.org/esp-syn/text/2105.html.

- ↑ Davidson, C. (5 June 1991). "Europe United with Multimedia". Open Syst. 2 (5): 28–30. https://archive.org/details/sim_world-publishing-monitor_1991-08_1_8_0/page/725/mode/1up. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ↑ "Olivetti relinquishes majority control of Acorn". Acorn User: pp. 10. April 1996. https://archive.org/details/AcornUser167-Apr96/page/n9/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Olivetti Sells Shares in Acorn Computer". The New York Times (New York). 2 July 1996. https://www.nytimes.com/1996/07/02/business/international-briefs-olivetti-sells-shares-in-acorn-computer.html?scp=1&sq=acorn+computer&st=nyt. "Olivetti S.p.A. of Italy said yesterday that it had sold 14.7 percent of Acorn Computer Group P.L.C. to Lehman Brothers Inc. on Friday. Lehman did not disclose how much it paid, but at current market prices, the sale would have brought about L33.5 million ($52 million) to Olivetti, which has been posting losses. The purchase, representing 13.25 million of the British computer company's shares, reduced Olivetti's stake in Acorn to about 31.2 percent from 78.5 percent two years ago. Lehman said it intended to resell the shares to investors."

- ↑ Whytehead, Chris (31 October 2008). "Master 128". The Centre for Computing History. http://chrisacorns.computinghistory.org.uk/Computers/Master128.html.

- ↑ "The 200,000th Master finds a good home". Acorn Newsletter: pp. 3. March 1989. http://chrisacorns.computinghistory.org.uk/docs/Acorn/NL/Acorn_NewsIss9.pdf.

- ↑ Whytehead, Chris. "Master 512". The Centre for Computing History. http://chrisacorns.computinghistory.org.uk/Computers/Master512.html.

- ↑ Whytehead, Chris. "Master Turbo". The Centre for Computing History. http://chrisacorns.computinghistory.org.uk/Computers/MasterTurbo.html.