Royal Bank of Scotland Group

Topic: Company

From HandWiki - Reading time: 43 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 43 min

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Head Office of the Royal Bank of Scotland Group | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Public limited company | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

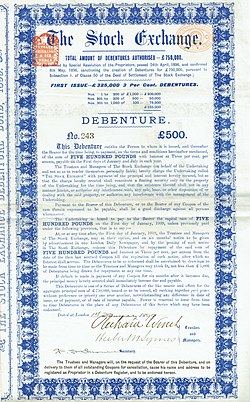

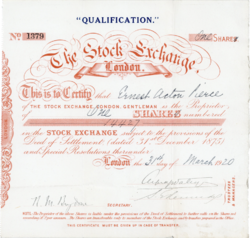

London Stock Exchange (LSE) is a stock exchange in the City of London, England , United Kingdom. As of August 2023,[update] the total market value of all companies trading on the LSE stood at $3.18 trillion.[3] Its current premises are situated in Paternoster Square close to St Paul's Cathedral in the City of London. Since 2007, it has been part of the London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG (LSE: [Script error: No such module "Stock tickers/LSE". LSEG])).[4] The LSE is the most-valued stock exchange in Europe as of 2023.[5] According to the 2020 Office for National Statistics report, approximately 12% of UK-resident individuals reported having investments in stocks and shares.[6] According to the 2020 Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) report, approximately 15% of UK adults reported having investments in stocks and shares.[7] HistoryCoffee HouseThe Royal Exchange had been founded by English financier Thomas Gresham and Sir Richard Clough on the model of the Antwerp Bourse. It was opened by Elizabeth I of England in 1571.[8][9] During the 17th century, stockbrokers were not allowed in the Royal Exchange due to their rude manners. They had to operate from other establishments in the vicinity, notably Jonathan's Coffee-House. At that coffee house, a broker named John Castaing started listing the prices of a few commodities, such as salt, coal, paper, and exchange rates in 1698. Originally, this was not a daily list and was only published a few days of the week.[10] This list and activity was later moved to Garraway's coffee house. Public auctions during this period were conducted for the duration that a length of tallow candle could burn; these were known as "by inch of candle" auctions. As stocks grew, with new companies joining to raise capital, the royal court also raised some monies. These are the earliest evidence of organised trading in marketable securities in London. Royal ExchangeAfter Gresham's Royal Exchange building was destroyed in the Great Fire of London, it was rebuilt and re-established in 1669. This was a move away from coffee houses and a step towards the modern model of stock exchange.[11] The Royal Exchange housed not only brokers but also merchants and merchandise. This was the birth of a regulated stock market, which had teething problems in the shape of unlicensed brokers. In order to regulate these, Parliament passed an Act in 1697 that levied heavy penalties, both financial and physical, on those brokering without a licence. It also set a fixed number of brokers (at 100), but this was later increased as the size of the trade grew. This limit led to several problems, one of which was that traders began leaving the Royal Exchange, either by their own decision or through expulsion, and started dealing in the streets of London. The street in which they were now dealing was known as 'Exchange Alley', or 'Change Alley'; it was suitably placed close to the Bank of England. Parliament tried to regulate this and ban the unofficial traders from the Change streets. Traders became weary of "bubbles" when companies rose quickly and fell, so they persuaded Parliament to pass a clause preventing "unchartered" companies from forming. After the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), trade at Jonathan's Coffee House boomed again. In 1773, Jonathan, together with 150 other brokers, formed a club and opened a new and more formal "Stock Exchange" in Sweeting's Alley. This now had a set entrance fee, by which traders could enter the stock room and trade securities. It was, however, not an exclusive location for trading, as trading also occurred in the Rotunda of the Bank of England. Fraud was also rife during these times and in order to deter such dealings, it was suggested that users of the stock room pay an increased fee. This was not met well and ultimately, the solution came in the form of annual fees and turning the Exchange into a Subscription room. The Subscription room created in 1801 was the first regulated exchange in London, but the transformation was not welcomed by all parties. On the first day of trading, non-members had to be expelled by a constable. In spite of the disorder, a new and bigger building was planned, at Capel Court. William Hammond laid the first foundation stone for the new building on 18 May. It was finished on 30 December when "The Stock Exchange" was incised on the entrance. First Rule Book In the Exchange's first operating years, on several occasions there was no clear set of regulations or fundamental laws for the Capel Court trading. In February 1812, the General Purpose Committee confirmed a set of recommendations, which later became the foundation of the first codified rule book of the Exchange. Even though the document was not a complex one, topics such as settlement and default were, in fact, quite comprehensive. With its new governmental commandments[12] and increasing trading volume, the Exchange was progressively becoming an accepted part of the financial life in the city. In spite of continuous criticism from newspapers and the public, the government used the Exchange's organised market (and would most likely not have managed without it) to raise the enormous amount of money required for the wars against Napoleon. Foreign and regional exchangesAfter the war and facing a booming world economy, foreign lending to countries such as Brazil, Peru and Chile was a growing market. Notably, the Foreign Market at the Exchange allowed for merchants and traders to participate, and the Royal Exchange hosted all transactions where foreign parties were involved. The constant increase in overseas business eventually meant that dealing in foreign securities had to be allowed within all of the Exchange's premises. Just as London enjoyed growth through international trade, the rest of Great Britain also benefited from the economic boom. Two other cities, in particular, showed great business development: Liverpool and Manchester. Consequently, in 1836 both the Manchester and Liverpool stock exchanges were opened. Some stock prices sometimes rose by 10%, 20% or even 30% in a week. These were times when stockbroking was considered a real business profession, and such attracted many entrepreneurs. Nevertheless, with booms came busts, and in 1835 the "Spanish panic" hit the markets, followed by a second one two years later. The Exchange before the World Wars By June 1853, both participating members and brokers were taking up so much space that the Exchange was now uncomfortably crowded, and continual expansion plans were taking place. Having already been extended west, east, and northwards, it was then decided the Exchange needed an entire new establishment. Thomas Allason was appointed as the main architect, and in March 1854, the new brick building inspired from the Great Exhibition stood ready. This was a huge improvement in both surroundings and space, with twice the floor space available. By the late 1800s, the telephone, ticker tape, and the telegraph had been invented. Those new technologies led to a revolution in the work of the Exchange. First World War As the financial centre of the world, both the City and the Stock Exchange were hit hard by the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Due to fears that borrowed money was to be called in and that foreign banks would demand their loans or raise interest, prices surged at first. The decision to close the Exchange for improved breathing space and to extend the August Bank Holiday to prohibit a run on banks, was hurried through by the committee and Parliament, respectively. The Stock Exchange ended up being closed from the end of July until the New Year, causing street business to be introduced again, as well as the "challenge system". The Exchange was set to open again on 4 January 1915 under tedious restrictions: transactions were to be in cash only. Due to the limitations and challenges on trading brought by the war, almost a thousand members quit the Exchange between 1914 and 1918. When peace returned in November 1918, the mood on the trading floor was generally cowed. In 1923, the Exchange received its own coat of arms, with the motto Dictum Meum Pactum, My Word is My Bond. Second World WarIn 1937, officials at the Exchange used their experiences from World War I to draw up plans for how to handle a new war. The main concerns included air raids and the subsequent bombing of the Exchange's perimeters, and one suggestion was a move to Denham, Buckinghamshire. This however never took place. On the first day of September 1939, the Exchange closed its doors "until further notice" and two days later World War II was declared. Unlike in the prior war, the Exchange opened its doors again six days later, on 7 September. As the war escalated into its second year, the concerns for air raids were greater than ever. Eventually, on the night of 29 December 1940, one of the greatest fires in London's history took place. The Exchange's floor was hit by a clutch of incendiary bombs, which were extinguished quickly. Trading on the floor was now drastically low and most was done over the phone to reduce the possibility of injuries. The Exchange was only closed for one more day during wartime, in 1945 due to damage from a V-2 rocket. Nonetheless, trading continued in the house's basement. Post-war After decades of uncertain if not turbulent times, stock market business boomed in the late 1950s. This spurred officials to find new, more suitable accommodation. The work on the new Stock Exchange Tower began in 1967. The Exchange's new 321 feet (98 metres) high building had 26 storeys with council and administration at the top, and middle floors let out to affiliate companies. Queen Elizabeth II opened the building on 8 November 1972; it was a new City landmark, with its 23,000 sq ft (2,100 m2) trading floor.  1973 marked a year of changes for the Stock Exchange. First, two trading prohibitions were abolished. A report from the Monopolies and Mergers Commission recommended the admittance of both women and foreign-born members on the floor. Second, in March the London Stock Exchange formally merged with the eleven British and Irish regional exchanges, including the Scottish Stock Exchange.[13] This expansion led to the creation of a new position of Chief Executive Officer; after an extensive search this post was given to Robert Fell. There were more governance changes in 1991, when the governing Council of the Exchange was replaced by a Board of Directors drawn from the Exchange's executive, customer, and user base; and the trading name became "The London Stock Exchange". FTSE 100 Index (pronounced "Footsie 100") was launched by a partnership of the Financial Times and the Stock Exchange on 3 January 1984. This turned out to be one of the most useful indices of all, and tracked the movements of the 100 leading companies listed on the Exchange. IRA bombingOn 20 July 1990, a bomb planted by the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) exploded in the men's toilets behind the visitors' gallery. The area had already been evacuated and nobody was injured.[14] About 30 minutes before the blast at 8:49 a.m., a man who said he was a member of the IRA told Reuters that a bomb had been placed at the exchange and was about to explode. Police officials said that if there had been no warning, the human toll would have been very high.[15] The explosion ripped a hole in the 23-storey building in Threadneedle Street and sent a shower of glass and concrete onto the street.[16] The long-term trend towards electronic trading platforms reduced the Exchange's attraction to visitors, and although the gallery reopened, it was closed permanently in 1992. "Big Bang"The biggest event of the 1980s was the sudden de-regulation of the financial markets in the UK in 1986. The phrase "Big Bang" was coined to describe measures, including abolition of fixed commission charges and of the distinction between stockjobbers and stockbrokers on the London Stock Exchange, as well as the change from an open outcry to electronic, screen-based trading. In 1995, the Exchange launched the Alternative Investment Market, the AIM, to allow growing companies to expand into international markets. Two years later, the Electronic Trading Service (SETS) was launched, bringing greater speed and efficiency to the market. Next, the CREST settlement service was launched. In 2000, the Exchange's shareholders voted to become a public limited company, London Stock Exchange plc. London Stock Exchange also transferred its role as UK Listing Authority to the Financial Services Authority (FSA-UKLA). EDX London, an international equity derivatives business, was created in 2003 in partnership with OM Group. The Exchange also acquired Proquote Limited, a new generation supplier of real-time market data and trading systems.   The old Stock Exchange Tower became largely redundant with Big Bang, which deregulated many of the Stock Exchange's activities: computerised systems and dealing rooms replaced face-to-face trading. In 2004, London Stock Exchange moved to a brand-new headquarters in Paternoster Square, close to St Paul's Cathedral. In 2007, the London Stock Exchange merged with Borsa Italiana, creating London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG). The Group's headquarters are in Paternoster Square. The Stock Exchange in Paternoster Square was the initial target for the protesters of Occupy London on 15 October 2011. Attempts to occupy the square were thwarted by police.[17] Police sealed off the entrance to the square as it is private property, a High Court injunction having previously been granted against public access to the square.[18] The protesters moved nearby to occupy the space in front of St Paul's Cathedral.[19] The protests were part of the global Occupy movement. On 25 April 2019, the final day of the Extinction Rebellion disruption in London, 13 activists glued themselves together in a chain, blocking the entrances of the Stock Exchange.[20][21] The protesters were all later arrested on suspicion of aggravated trespass.[21] Extinction Rebellion had said its protesters would target the financial industry "and the corrosive impacts of the ... sector on the world we live in" and activists also blocked entrances to HM Treasury and the Goldman Sachs office on Fleet Street.[22] ActivitiesPrimary marketsThere are two main markets on which companies trade on the LSE: the main market and the alternative investment market. Main MarketThe main market is home to over 1,300 large companies from 60 countries.[23] The FTSE 100 Index ("footsie") is the main share index of the 100 most highly capitalised UK companies listed on the Main Market.[24] Alternative Investment MarketThe Alternative Investment Market is LSE's international market for smaller companies. A wide range of businesses including early-stage, venture capital-backed, as well as more-established companies join AIM seeking access to growth capital. The AIM is classified as a Multilateral Trading Facility (MTF) under the 2004 MiFID directive, and as such it is a flexible market with a simpler admission process for companies wanting to be publicly listed.[25] Secondary marketsThe securities available for trading on London Stock Exchange:[26]

Post tradeThrough the Exchange's Italian arm, Borsa Italiana, the London Stock Exchange Group as a whole offers clearing and settlement services for trades through CC&G (Cassa di Compensazione e Garanzia) and Monte Titoli.[27][28] is the Groups Central Counterparty (CCP) and covers multiple asset classes throughout the Italian equity, derivatives and bond markets. CC&G also clears Turquoise derivatives. Monte Titoli (MT) is the pre-settlement, settlement, custody and asset services provider of the Group. MT operates both on-exchange and OTC trades with over 400 banks and brokers. TechnologyLondon Stock Exchange's trading platform is its own Linux-based edition named Millennium Exchange.[29] Their previous trading platform TradElect was based on Microsoft's .NET Framework, and was developed by Microsoft and Accenture. For Microsoft, LSE was a good combination of a highly visible exchange and yet a relatively modest IT problem.[30] Despite TradElect only being in use for about two years,[31] after suffering multiple periods of extended downtime and unreliability[32][33] the LSE announced in 2009 that it was planning to switch to Linux in 2010.[34][35] The main market migration to MillenniumIT technology was successfully completed in February 2011.[36] LSEG provides high-performance technology, including trading, market surveillance and post-trade systems, for over 40 organisations and exchanges, including the Group's own markets. Additional services include network connectivity, hosting and quality assurance testing. MillenniumIT, GATElab and Exactpro are among the Group's technology companies.[37] The LSE facilitates stock listings in a currency other than its "home currency". Most stocks are quoted in GBP but some are quoted in EUR while others are quoted in USD. Mergers and acquisitionsOn 3 May 2000, it was announced that the LSE would merge with the Deutsche Börse; however this fell through.[38] On 23 June 2007, the London Stock Exchange announced that it had agreed on the terms of a recommended offer to the shareholders of the Borsa Italiana S.p.A. The merger of the two companies created a leading diversified exchange group in Europe. The combined group was named the London Stock Exchange Group, but still remained two separate legal and regulatory entities. One of the long-term strategies of the joint company is to expand Borsa Italiana's efficient clearing services to other European markets. In 2007, after Borsa Italiana announced that it was exercising its call option to acquire full control of MBE Holdings; thus the combined Group would now control Mercato dei Titoli di Stato, or MTS. This merger of Borsa Italiana and MTS with LSE's existing bond-listing business enhanced the range of covered European fixed income markets. London Stock Exchange Group acquired Turquoise (TQ), a Pan-European MTF, in 2009.[39] On 9 October 2020, London Stock Exchange agreed to sell the Borsa Italiana (including Borsa's bond trading platform MTS) to Euronext for €4.3 billion (£3.9 billion) in cash.[40] Euronext completed the acquisition of the Borsa Italiana Group on 29 April 2021 for a final price of €4,444 million.[41] On 12 Dec 2022, Microsoft bought a nearly 4% stake in LSE (London Stock Exchange Group) as part of a ten-year cloud deal.[42] NASDAQ bidsIn December 2005, London Stock Exchange rejected a £1.6 billion takeover offer from Macquarie Bank. London Stock Exchange described the offer as "derisory", a sentiment echoed by shareholders in the Exchange. Shortly after Macquarie withdrew its offer, the LSE received an unsolicited approach from NASDAQ valuing the company at £2.4 billion. This too it rejected. NASDAQ later pulled its bid, and less than two weeks later on 11 April 2006, struck a deal with LSE's largest shareholder, Ameriprise Financial's Threadneedle Asset Management unit, to acquire all of that firm's stake, consisting of 35.4 million shares, at £11.75 per share.[43] NASDAQ also purchased 2.69 million additional shares, resulting in a total stake of 15%. While the seller of those shares was undisclosed, it occurred simultaneously with a sale by Scottish Widows of 2.69 million shares.[44] The move was seen as an effort to force LSE to the negotiating table, as well as to limit the Exchange's strategic flexibility.[45] Subsequent purchases increased NASDAQ's stake to 25.1%, holding off competing bids for several months.[46][47][48] United Kingdom financial rules required that NASDAQ wait for a period of time before renewing its effort. On 20 November 2006, within a month or two of the expiration of this period, NASDAQ increased its stake to 28.75% and launched a hostile offer at the minimum permitted bid of £12.43 per share, which was the highest NASDAQ had paid on the open market for its existing shares.[49] The LSE immediately rejected this bid, stating that it "substantially undervalues" the company.[50] NASDAQ revised its offer (characterized as an "unsolicited" bid, rather than a "hostile takeover attempt") on 12 December 2006, indicating that it would be able to complete the deal with 50% (plus one share) of LSE's stock, rather than the 90% it had been seeking. The U.S. exchange did not, however, raise its bid. Many hedge funds had accumulated large positions within the LSE, and many managers of those funds, as well as Furse, indicated that the bid was still not satisfactory. NASDAQ's bid was made more difficult because it had described its offer as "final", which, under British bidding rules, restricted their ability to raise its offer except under certain circumstances. In the end, NASDAQ's offer was roundly rejected by LSE shareholders. Having received acceptances of only 0.41% of rest of the register by the deadline on 10 February 2007, Nasdaq's offer duly lapsed.[51] On 20 August 2007, NASDAQ announced that it was abandoning its plan to take over the LSE and subsequently look for options to divest its 31% (61.3 million shares) shareholding in the company in light of its failed takeover attempt.[52] In September 2007, NASDAQ agreed to sell the majority of its shares to Borse Dubai, leaving the United Arab Emirates-based exchange with 28% of the LSE.[53] Proposed merger with TMX GroupOn 9 February 2011, London Stock Exchange Group announced it had agreed to merge with the Toronto-based TMX Group, the owners of the Toronto Stock Exchange, creating a combined entity with a market capitalization of listed companies equal to £3.7 trillion.[54] Xavier Rolet, CEO of the LSE Group at the time, would have headed the new enlarged company, while TMX Chief Executive Thomas Kloet would have become the new firm president. London Stock Exchange Group however announced it was terminating the merger with TMX on 29 June 2011 citing that "LSEG and TMX Group believe that the merger is highly unlikely to achieve the required two-thirds majority approval at the TMX Group shareholder meeting".[55] Even though LSEG obtained the necessary support from its shareholders, it failed to obtain the required support from TMX's shareholders. Opening timesNormal trading sessions on the main orderbook (SETS) are from 08:00 to 16:30 local time every day of the week except Saturdays, Sundays and holidays declared by the exchange in advance. The detailed schedule is as follows:

[56] Auction Periods (SETQx) SETSqx (Stock Exchange Electronic Trading Service – quotes and crosses) is a trading service for securities less liquid than those traded on SETS. The auction uncrossings are scheduled to take place at 8:00, 9:00, 11:00, 14:00, and 16:35. Observed holidays are New Year's Day, Good Friday, Easter Monday, May Bank Holiday, Spring Bank Holiday, Summer Bank Holiday, Christmas Day, and Boxing Day. If New Year's Day, Christmas Day, and/or Boxing Day falls on a weekend, the following working day is observed as a holiday. Arms

See also

References

Further reading

External links

[ ⚑ ] 51°30′54.25″N 0°5′56.77″W / 51.5150694°N 0.0991028°W

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Industry |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Founded | 1969[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Headquarters | Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Area served | Worldwide | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Products |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Revenue | £14.253 billion (2019)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| £4.232 billion (2019)[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| £3.800 billion (2019)[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total assets | £723.039 billion (2019)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Total equity | £43.556 billion (2019)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | UK Government Investments (62.4%)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Number of employees | 67,000 (2018)[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Subsidiaries |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc (also known as RBS Group) is a partly state-owned British banking and insurance holding company, based in Edinburgh, Scotland. The group operates a wide variety of banking brands offering personal and business banking, private banking, insurance and corporate finance through its offices located in Europe, North America and Asia. In the United Kingdom, its main subsidiary companies are The Royal Bank of Scotland,[5] NatWest, Ulster Bank, NatWest Markets, and Coutts.[6] The group issues banknotes in Scotland and Northern Ireland; as of 2014, the Royal Bank of Scotland was the only bank in the UK to still print £1 notes.[7]

Outside the UK, from 1988 to 2015 it owned Citizens Financial Group, a bank in the United States , and from 2005 to 2009 it was the second-largest shareholder in the Bank of China, itself the world's fifth-largest bank by market capitalisation in February 2008.[8]

Before the 2008 collapse and the general financial crisis, RBS was very briefly the largest bank in the world, and for a period was the second-largest bank in the UK and Europe and the fifth-largest in the world by market capitalisation. Subsequently, with a slumping share price and major loss of confidence, the bank fell sharply in the rankings, although in 2009 it was briefly the world's largest company by both assets (£1.9 trillion) and liabilities (£1.8 trillion).[9] It had to be bailed out by the UK government through the 2008 United Kingdom bank rescue package.[10]

The government, as of June 2018, holds and manages a 62.4% stake through UK Government Investments.[3]

In addition to its primary share listing on the London Stock Exchange, the company is also listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

On 14 February 2020, it was announced that RBS Group was to be renamed NatWest Group, taking the brand under which the majority of its business is delivered.[11][12][13] On 16 July 2020 the company announced that the rebrand would take place on 22 July 2020 but that it would make a subsequent announcement as to when the name change for the company would take effect.[14]

History

By 1969, economic conditions were becoming more difficult for the banking sector. In response, the National Commercial Bank of Scotland merged with the Royal Bank of Scotland.[15] The resulting company had 662 branches. The merger resulted in a new holding company, National and Commercial Banking Group Ltd. The English and Welsh branches were reorganised, until 1985, as Williams & Glyn's Bank, while the Scottish branches all transferred to the Royal Bank name. The holding company was renamed The Royal Bank of Scotland Group in 1979.[16]

Takeover bids

During the late 1970s and early 1980s the Royal Bank was the subject of three separate takeover approaches. In 1979, Lloyds Bank, which had previously built up a 16.4% stake in the Royal Bank, made a takeover approach for the remaining shares it did not own. The offer was rejected by the board of directors on the basis that it was detrimental to the bank's operations. However, when the Standard Chartered Bank proposed a merger with the Royal Bank in 1980, the board responded favourably. Standard Chartered Bank was headquartered in London, although most of its operations were in the Far East, and the Royal Bank saw advantages in creating a truly international banking group. Approval was received from the Bank of England, and the two banks agreed a merger plan that would have seen the Standard Chartered acquire the Royal Bank and keep the UK operations based in Edinburgh. However, the bid was scuppered by the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) which tabled a rival offer. The bid by HSBC was not backed by the Bank of England and was subsequently rejected by the Royal Bank's board. However, the British government referred both bids to the Monopolies and Mergers Commission; both were subsequently rejected as being against the public interest.[17]

The Bank did obtain an international partnership with Banco Santander Central Hispano of Spain, each bank taking a 5% stake in the other. However, this arrangement ended in 2005, when Banco Santander Central Hispano acquired UK bank Abbey National – and both banks sold their respective shareholdings.[18]

International expansion

The first international office of the bank was opened in New York in 1960. Subsequent international banks were opened in Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston and Hong Kong. In 1988 the bank acquired Citizens Financial Group, a bank based in Rhode Island, United States. Since then, Citizens has acquired several other American banks and in 2004 acquired Charter One Bank.[19]

Much later, the bank announced it was to scale back its international presence. "Let me spell it out very clearly: the days when RBS sought to be the biggest bank in the world, those days are well and truly over", Chief Executive Ross McEwan, who had been in charge of the bank for four months, said in unveiling plans to reduce costs by £5bn over four years. "Our ambition is to be a bank for U.K. customers", he added.[20]

National Westminster Bank

The late 1990s saw a new wave of consolidation in the financial services sector. In 1997, RBS formed a joint venture to set up Tesco Bank.[21][22] In 1999, the Bank of Scotland launched a hostile takeover bid for English rival NatWest. The Bank of Scotland intended to fund the deal by selling off many of the NatWest's subsidiary companies, including Ulster Bank and Coutts. However, the Royal Bank of Scotland subsequently tabled a counter-offer, sparking off the largest hostile takeover battle in UK corporate history. A key differentiation from the Bank of Scotland's bid was the Royal Bank of Scotland's plan to retain all of NatWest's subsidiaries. Although NatWest, one of the "Big Four" English clearing banks, was significantly larger than either Scottish bank, it had a recent history of poor financial performance and plans to merge with insurance company Legal & General were not well received, prompting a 26% fall in share price.[23]

On 11 February 2000, The Royal Bank of Scotland was declared the winner in the takeover battle, becoming the second largest banking group in the UK after HSBC Holdings. NatWest and the Royal Bank of Scotland became subsidiaries of the holding company, The Royal Bank of Scotland Group. NatWest as a distinct banking brand was retained, although many back-office functions of the bank were merged with the Royal Bank's, leading to over 18,000 job losses throughout the UK.[24]

Further expansion

In August 2005, the bank expanded into China, acquiring a 10% stake in the Bank of China for £1.7 billion.[25]

A new international headquarters was built at Gogarburn on the outskirts of Edinburgh, and was opened by Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh in 2005.[26]

The group was part of a consortium with Belgian bank Fortis and Spanish bank Banco Santander that acquired Dutch bank ABN AMRO on 10 October 2007. Rivals speculated that RBS had overpaid for the Dutch bank[27] although the bank pointed out that of the £49bn paid for ABN AMRO, RBS's share was only £10bn (equivalent to £167 per citizen of the UK).[28]

Coutts Bank's international businesses were renamed RBS Coutts on 1 January 2008 and remained as such until 2011, when they were rebranded Coutts & Co. Limited.[29]

2008–2009 financial crisis

On 22 April 2008 RBS announced a rights issue which aimed to raise £12bn in new capital to offset a writedown of £5.9bn resulting from credit market positions and to shore up its reserves following the purchase of ABN AMRO. This was, at the time, the largest rights issue in British corporate history.[30]

The bank also announced that it would review the possibility of divesting some of its subsidiaries to raise further funds, notably its insurance divisions Direct Line and Churchill.[31] Additionally, the bank's stake in Tesco Bank was bought by Tesco for £950 million in 2008.[21][22]

On 13 October 2008, in a move aimed at recapitalising the bank, it was announced that the British Government would take a stake of up to 58% in the Group. The aim was to "make available new tier 1 capital to UK banks and building societies to strengthen their resources permitting them to restructure their finances, while maintaining their support for the real economy, through the recapitalisation scheme which has been made available to eligible institutions".[32]

HM Treasury injected £37 billion ($64 billion, €47 billion, equivalent to £617 per citizen of the UK) of new capital into Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc, Lloyds TSB and HBOS plc, to avert financial sector collapse. The government stressed, however, that it was not "standard public ownership" and that the banks would return to private investors "at the right time".[33][34]

Alistair Darling, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, stated that the UK government would benefit from its rescue plan, for it would have some control over RBS in exchange for £5 billion in preference shares and underwriting the issuance of a further £15 billion in ordinary shares. If shareholder take-up of the share issue was 0%, then total government ownership in RBS would be 58%; and, if shareholder take-up was 100%, then total government ownership in RBS would be 0%.[35] Less than 56 million new shares were taken up by investors, or 0.24pc of the total offered by RBS in October 2008.[36]

As a consequence of this rescue, the Chief Executive of the group, Fred Goodwin, offered his resignation and it was duly accepted. Sir Tom McKillop confirmed that he would stand down from his role as chairman when his contract expired in March 2009. Goodwin was replaced by Stephen Hester, previously the Chief Executive of British Land, who commenced work at the Royal Bank of Scotland in November 2008.[37]

On 19 January 2009, the British Government announced a further injection of funds into the UK banking system in an attempt to restart personal and business lending. This would involve the creation of a state-backed insurance scheme which would allow banks to insure against existing loans going into default, in an attempt to restore the banks' confidence.[38]

At the same time the government announced its intention to convert the preference shares in RBS that it had acquired in October 2008 to ordinary shares. This would remove the 12% coupon payment (£600m p.a) on the shares but would increase the state's holding in the bank from 58% to 70%.[39]

On the same day RBS released a trading statement in which it expected to post full-year trading losses (before writedowns) of between £7bn and £8bn. The group also announced writedowns on goodwills (primarily related to the takeover of Dutch bank ABN-AMRO) of around £20bn. The combined total of £28bn would be the biggest ever annual loss in UK corporate history (the actual figure was £24.1bn). As a result, during the Blue Monday Crash, the group's share price fell over 66% in one day to 10.9p per share, from a 52-week high of 354p per share, itself a drop of 97%.[39]

Mid-2008 onwards

RBS' contractual commitment to retain the 4.26% Bank of China (BoC) stake ended on 31 December 2008, and the shares were sold on 14 January 2009. Exchange rate fluctuations meant that RBS made no profit on the deal. The Scottish press suggested two reasons for the move: the need for a bank mainly owned by HM Treasury to focus scarce capital on British markets, and the growth possibility of RBS's own China operations.[40][41]

Also in March 2009, RBS revealed that its traders had been involved in the purchase and sale of sub-prime securities under the supervision of Fred Goodwin.[42]

In September 2009, RBS and NatWest announced dramatic cuts in their overdraft fees including the unpaid item fee (from £38 to £5), the card misuse fee (from £35 to £15) and the monthly maintenance charge for going overdrawn without consent (from £28 to £20).[43] The cuts came at a time when the row over the legality of unauthorised borrowing reached the House of Lords. The fees were estimated to earn current account providers about £2.6bn a year.[44] The Consumers' Association chief executive, Peter Vicary-Smith, said: "This is a step in the right direction and a victory for consumer pressure."[43]

In November 2009, RBS announced plans to cut 3,700 jobs in addition to 16,000 already planned, while the government increased its stake in the company from 70% to 84%.[45]

In December 2009, the RBS board revolted against the main shareholder, the British government. They threatened to resign unless they were permitted to pay bonuses of £1.5bn to staff in its investment arm.[46]

More than 100 senior bank executives at the Royal Bank of Scotland were paid more than £1 million in late 2010 and total bonus payouts reached nearly £1 billion – even though the bailed-out bank reported losses of £1.1 billion for 2010. The 2010 figure was an improvement on the loss of £3.6 billion in 2009 and the record-breaking £24bn loss in 2008. The bonuses for staff in 2010 topped £950 million. The CEO Stephen Hester got £8 million in payments for the year. Len McCluskey, the general secretary of Unite the Union, said: "Taxpayers will be baffled as to how it is possible that while we own 84% of this bank it continues to so handsomely reward its investment bankers."[47]

In October 2011, Moody's downgraded the credit rating of 12 UK financial firms, including RBS, blaming financial weakness.[48]

In January 2012, there was press controversy about Hester's bonus—Hester was offered share options with a total value of £963,000 that would be held in long-term plans, and only paid out if he met strict and tough targets. If he failed to do this, it would be clawed-back. The Treasury permitted the payment because they feared the resignation of Hester and much of the board if the payment was vetoed by the government as the majority shareholder.[49] After a large amount of criticism[50][51][52][53] in the press, news emerged of Chairman Sir Philip Hampton turning down his own bonus of £1.4 million several weeks before the controversy.[51] Hester, who had been on holiday in Switzerland at the time, turned down his own bonus shortly after.[54]

In June 2012, a failure of an upgrade to payment processing software meant that a substantial proportion of customers could not transfer money to or from their accounts. This meant that RBS had to open a number of branches on a Sunday – the first time that they had had to do this.[55]

RBS released a statement on 12 June 2013 that announced a transition in which CEO Stephen Hester would stand down in December 2013 for the financial institution "to return to private ownership by the end of 2014". For his part in the procession of the transition, Hester would receive 12 months' pay and benefits worth £1.6 million, as well as the potential for £4 million in shares. The RBS stated that, as of the announcement, the search for Hester's successor would commence.[56] Ross McEwan, the head of retail banking at RBS, was selected to replace Hester in July 2013.[57]

On 4 August 2015 the UK government began the process of selling shares back to the private sector, reducing its ownership of ordinary shares from 61.3% to 51.5% and its total economic ownership (including B shares) from 78.3% to 72.9%. On 5 June 2018 the government reduced its ownership through UK Government Investments to 62.4%[58] at a loss of £2 billion.[59]

Restructuring

In June 2008 RBS sold the subsidiary Angel Trains for £3.6bn as part of an assets sale to raise cash.[60]

In March 2009, RBS announced the closure of its tax avoidance department, which had helped it avoid £500m of tax by channelling billions of pounds through securitised assets in tax havens such as the Cayman Islands. The closure was partly due to a lack of funds to continue the measures, and partly due to the 84% government stake in the bank.[61]

On 29 March 2010, GE Capital acquired Royal Bank of Scotland's factoring business in Germany. GE Capital signed an agreement with the Royal Bank of Scotland plc (RBS) to acquire 100% of RBS Factoring GmbH, RBS's factoring and invoice financing business in Germany, for an undisclosed amount. The transaction is subject to a number of conditions, including regulatory approval.[62]

Due to pressure from the UK government to shut down risky operations and prepare for tougher international regulations, in January 2012 the bank announced it would cut another 4,450 jobs and close its loss-making cash equities, corporate broking, equity capital markets, and mergers and acquisitions businesses. The move brought the total number of jobs cut since the bank was bailed out in 2008 to 34,000.[63][64]

During 2012, RBS separated its insurance business from the main group to form the Direct Line Group,[65] made up of several well-known brands including Direct Line and Churchill. RBS sold a 30% holding in the group through an initial public offering in October 2012.[66] Further shares sales in 2013 reduced RBS' holding to 28.5% by September 2013,[67] and RBS sold its remaining shares in February 2014.[68]

RBS sold its remaining stake in Citizens Financial Group in October 2015, having progressively reduced its stake through an initial public offering (IPO) started in 2014.[69]

Williams & Glyn divestment

As a condition of the British Government purchasing an 81% shareholding in the group, the European Commission ruled that the group sell a portion of its business, as the purchase was categorised as state aid. In August 2010, the group reached an agreement to sell 318 branches to Santander UK, made up of the RBS branches in England and Wales and the NatWest branches in Scotland.[70] Santander withdrew from the sale on 12 October 2012.[71]

In September 2013, the group confirmed it had reached an agreement to sell 314 branches to the Corsair consortium, made up of private equity firms and a number of institutional investors, including the Church Commissioners, which controls the property and investment assets of the Church of England. The branches, incorporating 250,000 small business customers, 1,200 medium business customers and 1.8 million personal banking customers, were due to be separated from the group in 2016 as a standalone business. The planned company would have traded as an ethical bank,[72] using the dormant Williams & Glyn's brand.[73]

In August 2016, RBS cancelled its plan to spin off Williams & Glyn as a separate business, stating that the new bank could not survive independently. It revealed it would instead seek to sell the operation to another bank.[74]

In February 2017, HM Treasury suggested that the bank should abandon the plan to sell the operation, and instead focus on initiatives to boost competition within business banking in the United Kingdom. This plan was formally approved by the European Commission in September 2017.[75]

Name change

In February 2020, RBS Group announced its intention to change its name to NatWest Group plc later in the year.[76]

Corporate structure

RBS is split into four main customer-facing franchises, each with several subsidiary businesses, and it also has a number of support functions.[77]

Personal Banking

thumb|Child & Co's headquarters in Fleet Street. The brand focuses on private banking. The segment comprises retail banking. In the United Kingdom, the group trades under the NatWest, Royal Bank of Scotland and Ulster Bank names. The CEO of this franchise is Les Matheson. Key subsidiaries include:

- NatWest

- Royal Bank of Scotland

- Ulster Bank

Commercial Banking

This franchise serves UK corporate and commercial customers, from SMEs to UK-based multinationals, and is the largest provider of banking, finance and risk management services to UK corporate and commercial customers. It also contains Lombard entity providing asset finance to corporate and commercial customers as well as some of the clients within the Private Banking franchise. The CEO of this franchise is Paul Thwaite.

Private Banking

This franchise serves high net worth customers. The key private banking subsidiaries and brands of NatWest Group that are included in this franchise are:

- Coutts & Co

- Adam and Company

- Drummonds Bank

- Child & Co.

NatWest Markets

This segment, commonly referred to as the investment banking arm of RBS, provides investment banking services and integrated financial solutions to major corporations and financial institutions around the world. NWMs areas of strength are debt financing, risk management, and investment and advisory services. NatWest Markets Securities is a key subsidiary, operating in the United States . The Interim CEO is Robert Begbie appointed in December 2019. [78]

Support functions

The group is supported by a number of functions and services departments – procurement, technology, payments, anti-money laundering, property, etc. – and support and control functions: the areas which provide core services across the bank – human resources, corporate governance, internal audit, legal, risk, etc.

Branding

RBS uses branding developed for the Bank on its merger with the National Commercial Bank of Scotland in 1969.[79] The bank's logo takes the form of an abstract symbol of four inward-pointing arrows known as the "Daisy Wheel" and is based on an arrangement of 36 piles of coins in a 6 by 6 square,[79] representing "the accumulation and concentration of wealth by the Group".[79]

Controversies

Media commentary and criticism

During Goodwin's tenure as CEO he attracted some criticism for lavish spending, including on the construction of a £350m headquarters in Edinburgh opened by the Queen in 2005[80] and $500m headquarters in the US begun in 2006,[81] and the use of a Dassault Falcon 900 jet owned by leasing subsidiary Lombard for occasional corporate travel.[82]

In February 2009 RBS reported that while Fred Goodwin was at the helm it had posted a loss of £24.1bn, the biggest loss in UK corporate history.[83] His responsibility for the expansion of RBS, which led to the losses, has drawn widespread criticism. His image was not enhanced by the news that emerged in questioning by the Treasury Select Committee of the House of Commons on 10 February 2009, that Goodwin has no technical bank training, and has no formal banking qualifications.[84]

In January 2009 The Guardian 's City editor Julia Finch identified him as one of twenty-five people who were at the heart of the financial meltdown.[85] Nick Cohen described Goodwin in The Guardian as "the characteristic villain of our day", who made £20m from RBS and left the government "with an unlimited liability for the cost of cleaning up the mess".[86] An online column by Daniel Gross labelled Goodwin "The World's Worst Banker",[81][87] a phrase echoed elsewhere in the media.[88][89] Gordon Prentice MP argued that his knighthood should be revoked as it is "wholly inappropriate and anomalous for someone to retain such a reward in these circumstances."[90]

Other members have also frequently been criticised as "fat cats" over their salary, expenses, bonuses and pensions.[91][92][93][94][95][96][97]

Fossil fuel financing

RBS was challenged over its financing of oil and coal mining by charities such as Platform London and Friends of the Earth. In 2007, RBS was promoting itself as "The Oil & Gas Bank", although the website www.oilandgasbank.com was later taken down.[98] A Platform London report criticised the bank's lending to oil and gas companies, estimating that the carbon emissions embedded within RBS' project finance reached 36.9 million tonnes in 2005, comparable to Scotland's carbon emissions.[99]

RBS provides the financial means for companies to build coal-fired power stations and dig new coal mines at sites throughout the world. RBS helped to provide an estimated £8 billion from 2006 to 2008 to energy corporation E.ON and other coal-utilising companies.[100] In 2012, 2.8% of RBS' total lending was provided to the power, oil and gas sectors combined. According to RBS' own figures, half of its deals to the energy sector were to wind power projects; although, this only included project finance and not general commercial loans.[101]

Huntingdon Life Sciences

In 2000 and 2001, staff of the bank were threatened over its provision of banking facilities for the animal testing company Huntingdon Life Sciences. The intimidation resulted in RBS withdrawing the company's overdraft facility, requiring the company to obtain alternative funding within a tight deadline.[102][103]

Canadian oil sands

Climate Camp activists criticise RBS for funding firms which extract oil from Canadian oil sands.[104] The Cree aboriginal group describe RBS as being complicit in "the biggest environmental crime on the planet".[105] In 2012, 7.2% of RBS' total oil and gas lending was to companies who derived more than 10% of their income from oil sands operations.[101]

See also

- List of banks in the United Kingdom

- List of systemically important banks

- Systemically important financial institution

- Too big to fail

- European Financial Services Roundtable

- High-yield debt

- Inter-Alpha Group of Banks

References

- ↑ RBS heritage hub. "Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc | RBS Heritage Hub". Rbs.com. https://www.rbs.com/heritage/companies/the-royal-bank-of-scotland-group-plc.html. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Annual Results 2019". Royal Bank of Scotland Group. https://www.investors.rbs.com/~/media/Files/R/RBS-IR/results-center/rbsg-ara-2019-140220-0245-v3.pdf. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ↑ "Fact sheet". Citywire. http://citywire.co.uk/new_model_adviser/share-prices-and-performance/share-factsheet.aspx?InstrumentID=170527. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ↑ The Scottish Gaelic name (Scottish Gaelic: Banca Rìoghail na h-Alba) is used by its retail banking branches in parts of Scotland, especially in signage and customer stationery.

- ↑ "The Royal Bank of Scotland". Scotbanks.org. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110719141712/http://www.scotbanks.org.uk/member_royal_bank_of_scotland.php. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "Current Banknotes". Committee of Scottish Bankers. http://www.scotbanks.org.uk/banknote_denominations.php. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ "World's largest banks". Financialranks.com. 5 February 2008. http://financialranks.com/?p=69. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ RBS et mon droit: HM deficits (FT Alphaville, accessed 20 January 2009)

- ↑ Barker, Alex (8 October 2008). "Brown says UK leads world with rescue". Financial Times. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/a3fb9670-951c-11dd-aedd-000077b07658.html?nclick_check=1. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ↑ Makortoff, Kalyeena RBS will change name to NatWest as Alison Rose begins overhaul The Guardian, 14 February 2020

- ↑ RBS Group to change its name to NatWest BBC News, 14 February 2020

- ↑ "Our plan to change our parent name". RBS. 14 February 2020. https://www.rbs.com/rbs/about/update-on-parent-name.html. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- ↑ "RBS to rebrand as Natwest Group next Wednesday". Practive Investor. https://www.proactiveinvestors.co.uk/companies/news/924385/rbs-to-rebrand-as-natwest-group-next-wednesday-924385.html. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- ↑ "National Commercial Bank of Scotland Ltd, Edinburgh, 1959–69". RBS Heritage Online. The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc. http://heritagearchives.rbs.com/wiki/National_Commercial_Bank_of_Scotland_Ltd%2C_Edinburgh%2C_1959-69. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Royal Bank of Scotland plc, Edinburgh, 1727-date". RBS Heritage Online. The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc. http://heritagearchives.rbs.com/wiki/The_Royal_Bank_of_Scotland_plc%2C_Edinburgh%2C_1727-date. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "The Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, Standard Chartered Bank Limited and The Royal Bank of Scotland Group Limited". Competition Commission. 2 September 2004. Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20110519000618/http://www.competition-commission.org.uk/rep_pub/reports/1982/150hongkong_shanghai_banking_corp_stand_chartered_bank_royal_bank_of__scotland_group_ltd.htm. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ William Kay (6 September 2004). "HBOS fury as EU backs Santander's Abbey bid". The Independent (London). https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/hbos-fury-as-eu-backs-santanders-abbey-bid-551521.html.

- ↑ "Citizens Financial Acquires Charter One". The New York Times. 5 May 2004. https://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/05/business/citizens-financial-acquires-charter-one.html?_r=0. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ↑ "RBS unveils plan to reduce global presence after posting big loss". Scotland News.Net. http://www.scotlandnews.net/index.php/sid/220259295/scat/5ba58fd38447f467/ht/RBS-unveils-plan-to-reduce-global-presence-after-posting-big-loss. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Tesco Pays £950m To Become Bank". Sky News. 28 July 2008. http://news.sky.com/skynews/Home/Business/Tesco-Pays-Royal-Bank-Of-Scotland-950m-In-New-Personal-Finance-Deal/Article/200807415058484?lpos=Business_2&lid=ARTICLE_15058484_Tesco%2BPays%2BRoyal%2BBank%2BOf%2BScotland%2B%25C2%25A3950m%2BIn%2BNew%2BPersonal%2BFinance%2BDeal. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Thelwell, Emma; Butterworth, Myra (28 July 2008). "Tesco eyes mortgages and current accounts in plan to take on UK's high street banks". The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/money/main.jhtml?view=DETAILS&grid=A1YourView&xml=/money/2008/07/28/bcntesco228.xml. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ↑ "NatWest takeover: a chronology". BBC News. 10 February 2000. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/626198.stm. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ↑ NatWest merger's mixed fortunes BBC News, 2000

- ↑ "RBS leads $3.1bn China investment". BBC News. 18 August 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/4162170.stm. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ↑ "New RBS headquarters". Scottish Government. 14 September 2005. http://www.scotland.gov.uk/News/Releases/2005/09/14110145. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ Sunderland, Ruth (8 October 2007). "Barclays boss: RBS overpaid for ABN Amro". The Guardian (London). https://www.theguardian.com/business/2007/oct/07/money1. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ↑ "Does RBS's acquisition of ABN AMRO really do what it says on the tin?". Cityam.com. http://www.cityam.com/index.php?news=8833. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "Coutts to drop RBS brand". 30 October 2011. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/4c8f95ac-0171-11e1-b177-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2NqAMHsr0. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ↑ "RBS rights issue". CNN. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20080518061624/http://www.cnn.com/2008/BUSINESS/05/15/rbs.rights.issue.ap/index.html.

- ↑ "RBS sets out £12bn rights issue". BBC News. 22 April 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/7359940.stm. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

- ↑ "Treasury statement on financial support to the banking industry" (Press release). HM Treasury. 13 October 2008. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ↑ "Brown: We'll be rock of stability". BBC News. 13 October 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/politics/7666695.stm. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ Jones, Sarah (13 October 2008). "bloomberg.com, Stocks Rebound After Government Bank Bailout; Lloyds Gains". Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601102&sid=aCMY6HCQ_Tjc&refer=ukU.K. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ Hélène Mulholland (13 October 2008). "Darling: UK taxpayer will benefit from banks rescue". The Guardian (UK). https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2008/oct/13/alistairdarling-economy. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ RBS now 58% owned by UK Government Telegraph, 28 November 2008

- ↑ "It is a good time for Hester to quit property for RBS". Thisislondon.co.uk. 14 October 2008. http://www.thisislondon.co.uk/standard-business/article-23572572-details/It%E2%80%99s+a+good+time+for+Hester+to+quit+property+for+RBS/article.do. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ UK banking plan faces criticism BBC News, 19 January 2009

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 RBS shares plunge on loss BBC News, 19 January 2009

- ↑ "RBS confirms sale of £1.6bn China stake". Edinburgh Evening News January (14). 2009. http://business.scotsman.com/bankinginsurance/RBS-confirms-sale-of-16bn.4873405.jp.

- ↑ Martin Flanagan (2009). "RBS sells Bank of China stake in a clear sign that retrenchment rules". The Scotsman January (14). http://business.scotsman.com/bankinginsurance/RBS-sells-Bank-of-China.4872360.jp.

- ↑ Winnett, Robert (20 March 2009). "RBS traders hid toxic debt". The Daily Telegraph (UK). https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/financetopics/recession/5025115/RBS-traders-hid-toxic-debt.html. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Jones, Rupert. "Royal Bank of Scotland and NatWest cut overdraft charges". The Guardian . 7 September 2009

- ↑ Osborne, Hilary. "Bank charges appeal reaches House of Lords". The Guardian 23 June 2009

- ↑ Jill Treanor (2 November 2009). "RBS axes 3,700 jobs as taxpayer stake hits 84%". Guardian (UK). https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/nov/02/rbs-slash-costs-cuts-jobs. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "RBS board could quit if government limits staff bonuses". BBC News. 3 December 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/8392147.stm. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ Treanor, Jill (21 February 2011). "RBS bankers get £950 million in bonuses despite £1.1bn loss". The Guardian (London). https://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/feb/24/rbs-bankers-bonuses-despite-loss.

- ↑ UK financial firms downgraded by Moody's rating agency, BBC News (7 October 2011)

- ↑ Treasury feared Hester and board would quit BBC 26 January 2012

- ↑ Stephen Hester bonus puts David Cameron under pressure Guardian, 27 January 2012

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Sir Philip Hampton waives £1.4m share award The Telegraph, 28 January 2012

- ↑ RBS chairman waives share-based bonus Reuters, 28 January 2012

- ↑ Ed Miliband must block Hester's Bonus Metro, 22 January 2012

- ↑ RBS boss Stephen Hester waives bonus: reaction The Guardian, 30 January 2012

- ↑ "Natwest Branches Open on Sunday To Help Customers After Computer Glitch". The Huffington Post UK. 24 June 2012. http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/2012/06/24/natwest-branches-open-on-sunday-computer-gitch_n_1621907.html. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ Robert Peston (12 June 2013). "Royal Bank of Scotland CEO Stephen Hester to stand down". BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-22881526. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ↑ Patrick Jenkins (31 July 2013). "RBS selects McEwan as new chief". Financial Times. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/0935a53c-fa0b-11e2-98e0-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3EMs3ySli. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ RBS, Equity Ownership Statistics, accessed 9 June 2018

- ↑ Agini, Samuel. "Government faces questions over £2bn hit on RBS share sale". Fnlondon.com. https://www.fnlondon.com/articles/uk-government-continues-privatisation-of-rbs-royal-bank-of-scotland-20180604. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ "RBS sells off rail stock business". BBC News. 13 June 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/7452205.stm. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ RBS avoided £500m of tax in global deals The Guardian , 13 March 2009

- ↑ "GE Capital Acquired Royal Bank of Scotland's Factoring Business in Germany". Businesswire.co.uk. 29 March 2010. http://www.businesswire.co.uk/portal/site/uk/permalink/?ndmViewId=news_view&newsId=20100329005696&newsLang=en. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ "RBS to cut 3,500 jobs over 3 years". 13 January 2012. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012. https://web.archive.org/web/20120115224649/http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2012/01/13/rbs-cut-3500-jobs-over-3-years.html.

- ↑ "RBS to cut 4,450 jobs in fresh jobs cull". Reuters. 12 January 2012. http://in.reuters.com/article/2012/01/12/rbs-idINDEE80B07C20120112.

- ↑ "Direct Line nears RBS separation". BBC News. 3 September 2012. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-scotland-business-19463398. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ Steve Slater (13 March 2013). "RBS races ahead with Direct Line sell-off". Reuters. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/03/13/uk-rbs-directline-sale-idUKBRE92C0DD20130313. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ "RBS makes £630m from sale of 20% of Direct Line". BBC News. 20 September 2013. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-24171522. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ "RBS set to make £1bn from remaining Direct Line stake". BBC News. 26 February 2014. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-26361479. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- ↑ "RBS profits rise on Citizens sale". BBC News. 30 October 2015. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-34674586. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ↑ Wray, Richard (4 August 2010). "Santander overtakes HSBC as it buys 318 RBS branches". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2010/aug/04/santander-royalbankofscotlandgroup.

- ↑ "RBS sale of 316 branches to Santander collapses". BBC News. 12 October 2012. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-19929376. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- ↑ "Church Commissioners Statement on RBS bid". The Church of England. 27 September 2013. http://www.churchofengland.org/media-centre/news/2013/09/church-commissioners-statement-on-rbs-bid.aspx. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ↑ "RBS sells 314 bank branches to Corsair consortium". BBC News. 27 September 2013. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-24304526. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- ↑ "RBS cancels Williams & Glyn project and loses another £2bn". The Telegraph. 5 August 2016. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2016/08/05/rbs-cancels-williams--glyn-project-and-loses-another-2bn/. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ↑ "RBS plans: Williams & Glyn sale should be dropped, UK says". BBC News. 17 February 2017. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-39010555. Retrieved 17 February 2017.

- ↑ "RBS Group to change its name to NatWest". BBC. 14 February 2020. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-51500062. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ↑ "Our executive management team". The Royal Bank of Scotland Group. https://www.rbs.com/rbs/about/board-and-governance/board-and-committees/executive-management-team.html. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ↑ "Robert Begbie, Interim CEO NatWest Markets". https://www.rbs.com/rbs/about/board-and-governance/board-and-committees/profiles/robert-begbie.html.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 RBS.com | About Us| Our History | Exhibition Feature | Building the Brand

- ↑ The Scotsman, 14 September 2005, Queen opens £350m bank HQ

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Slate, 1 December 2008 Who's the World's Worst Banker?

- ↑ The Times, 6 April 2004, Banking star brought down to earth over jet-set perk

- ↑ The Guardian , 26 February 2009, RBS record losses raise prospect of 95% state ownership

- ↑ "Exchiefs of Royal Bank of Scotland And HBOS Admitted To Having No Formal Banking Qualifications". The Herald. Archived from the original on 4 March 2009. https://web.archive.org/web/20090304140453/http://www.theherald.co.uk/news/news/display.var.2488353.0.Exchiefs_of_Royal_Bank_of_Scotland_and_HBOS_admitted_to_having_no_formal_banking_qualifications.php. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ↑ Julia Finch (26 January 2009). "Twenty-five people at the heart of the meltdown ... | Business". The Guardian (UK). https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/jan/26/road-ruin-recession-individuals-economy. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ↑ Cohen, Nick (18 January 2009). "It's not the poor the middle class really fear". The Guardian (UK). https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2009/jan/18/nick-cohen-middle-class. Retrieved 20 January 2009.

- ↑ "Economy: The World's Worst Banker | Newsweek Voices – Daniel Gross". Newsweek. 18 December 2008. http://www.newsweek.com/id/171688/page/1. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ↑ The Times, 20 January 2009, Hubris to nemesis: how Sir Fred Goodwin became the 'world's worst banker'

- ↑ The Journal, 26 January 2009, RBS's Fred Goodwin: the world's worst banker?

- ↑ "Ex-RBS chief 'should lose knighthood'". Politics.co.uk. http://www.politics.co.uk/news/economy-and-finance/ex-rbs-chief-should-lose-knighthood--$1267707.htm. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ↑ The Times, 13 October 2008, Brown targets fat cat pay after nationalising banks in £37 billion bailout

- ↑ The Mirror, 7 May 2009, RBS fat cat Gordon Pell given £10M pension pot

- ↑ The Guardian , 13 January 2010, Stephen Hester's fat-cat flap

- ↑ The Independent, 19 April 2004, RBS braced for shareholder showdown over fat cat bonuses

- ↑ Evening Standard, 5 February 2009, Bailed-out bankers facing curbs on fat cat bonuses

- ↑ The Scotsman, 1 February 2010, Billy Bragg takes his fight to limit RBS bonuses to Speakers' Corner

- ↑ The Telegraph, 27 March 2009, A game in which people are encouraged to get their revenge on the former Royal Bank of Scotland chief Sir Fred Goodwin has gone viral.

- ↑ "Dirty Money: Corporate Greenwash & RBS coal finance". Platform. March 2011. http://platformlondon.org/dm.pdf. Retrieved 13 February 2014.

- ↑ "The Oil & Gas Bank". Platform. March 2007. http://carbonweb.org/documents/Oil_&_Gas_Bank.pdf. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ↑ Terry Macalister (11 August 2008). "Climate change: High street banks face consumer boycott over investment in coal projects". Guardian (UK). https://www.theguardian.com/business/2008/aug/11/banking.ethicalbusiness. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 "Energy sector lending". Royal Bank of Scotland. Royal Bank of Scotland. 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20131212233927/http://www.rbs.com/sustainability/citizenship-and-environmental/energy-sector-lending.html. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ↑ Animal Rights news in the UK | Animal testing lab faces ruin as bank cancels overdraft

- ↑ Bright, Martin (21 January 2001). "Inside the labs where lives hang heavy in the balance". The Observer (UK). https://www.theguardian.com/Archive/Article/0,4273,4120748,00.html. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

- ↑ Katharine Ainger (27 August 2009). "The tactics of these rogue climate elements must not succeed". The Guardian (UK). https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2009/aug/27/climate-camp-takes-on-lobbyists. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ↑ Terry Macalister (23 August 2009). "Cree aboriginal group to join London climate camp protest over tar sands". Guardian (UK). https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/aug/23/london-tar-sands-climate-protest. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

External links

- Royal Bank of Scotland companies grouped at OpenCorporates

KSF

KSF