Shell plc

Topic: Company

From HandWiki - Reading time: 56 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 56 min

Logo designed by Raymond Loewy | |

Shell Centre headquarters in London | |

| Formerly |

|

|---|---|

| Type | Public limited company |

| ISIN | GB00BP6MXD84 |

| Industry |

|

| Predecessors |

|

| Founded | April 1907 (original amalgamation) 20 July 2005 in Shell Centre, London (current entity) |

| Founders | Marcus & Samuel Samuel (Shell Transport and Trading Co.) Jean B.A. Kessler Henri Deterding Hugo Loudon (Royal Dutch Petroleum Co.) |

| Headquarters | Shell Centre, , England, UK |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | |

| Products | |

| Brands |

|

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 86,000 (2022)[3] |

| Divisions |

|

| Subsidiaries | List

|

| Website | shell |

Footnotes / references

| |

Shell plc[1][4] is a British multinational oil and gas company headquartered in London.[5] Shell is a public limited company with a primary listing on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) and secondary listings on Euronext Amsterdam and the New York Stock Exchange. A core component of Big Oil, Shell is the second largest investor-owned oil and gas company in the world by revenue (after ExxonMobil), and among the world's largest companies out of any industry.[6] Measured by both its own emissions, and the emissions of all the fossil fuels it sells, Shell was the ninth-largest corporate producer of greenhouse gas emissions in the period 1988–2015.

Shell was formed in 1907 through the merger of Royal Dutch Petroleum Company of the Netherlands and The "Shell" Transport and Trading Company of the United Kingdom. The combined company rapidly became the leading competitor of the American Standard Oil and by 1920 Shell was the largest producer of oil in the world.[7] Shell first entered the chemicals industry in 1929. Shell was one of the "Seven Sisters" which dominated the global petroleum industry from the mid-1940s to the mid-1970s. In 1964, Shell was a partner in the world's first commercial sea transportation of liquefied natural gas (LNG).[8] In 1970, Shell acquired the mining company Billiton, which it subsequently sold in 1994 and now forms part of BHP. In recent decades gas has become an increasingly important part of Shell's business[9] and Shell acquired BG Group in 2016.[9]

Shell is vertically integrated and is active in every area of the oil and gas industry, including exploration, production, refining, transport, distribution and marketing, petrochemicals, power generation, and trading. Shell has operations in over 99 countries,[10] produces around 3.7 million barrels of oil equivalent per day and has around 44,000 service stations worldwide.[11][12] As of 31 December 2019, Shell had total proved reserves of 11.1 billion barrels (1.76×109 m3) of oil equivalent.[13] Shell USA, its principal subsidiary in the United States, is one of its largest businesses.[14] Shell holds 44%[15] of Raízen, a publicly-listed joint venture with Cosan, which is the third-largest Brazil -based energy company.[16] In addition to the main Shell brand, the company also owns the Jiffy Lube, Pennzoil and Quaker State brands.

Shell is a constituent of the FTSE 100 Index and had a market capitalisation of US$199 billion on 15 September 2022, the largest of any company listed on the LSE and the 44th-largest of any company in the world.[17] By 2021 revenues, Shell is the second-largest investor-owned oil company in the world (after ExxonMobil), the largest company headquartered in the United Kingdom, the second-largest company headquartered in Europe (after Volkswagen), and the 15th largest company in the world.[18] Until its unification in 2005 as Royal Dutch Shell plc, the firm operated as a dual-listed company, whereby the British and Dutch companies maintained their legal existence and separate listings but operated as a single-unit partnership. From 2005 to 2022, the company had its headquarters in The Hague, its registered office in London and had two types of shares (A and B). In January 2022, the firm merged the A and B shares, moved its headquarters to London, and changed its legal name to Shell plc.[5][19]

History

Origins

The Royal Dutch Shell Group was created in April 1907 through the amalgamation of two rival companies: the Royal Dutch Petroleum Company (Dutch: Koninklijke Nederlandse Petroleum Maatschappij) of the Netherlands and the Shell Transport and Trading Company Limited of the United Kingdom .[20] It was a move largely driven by the need to compete globally with Standard Oil.[21] The Royal Dutch Petroleum Company was a Dutch company founded in 1890 to develop an oilfield in Pangkalan Brandan, North Sumatra,[22] and initially led by August Kessler, Hugo Loudon, and Henri Deterding. The "Shell" Transport and Trading Company (the quotation marks were part of the legal name) was a British company, founded in 1897 by Marcus Samuel, 1st Viscount Bearsted, and his brother Samuel Samuel.[23] Their father had owned an antique company in Houndsditch, London,[24] which expanded in 1833 to import and sell seashells, after which the company "Shell" took its name.[20][25][26]

For various reasons, the new firm operated as a dual-listed company, whereby the merging companies maintained their legal existence but operated as a single-unit partnership for business purposes. The terms of the merger gave 60 percent stock ownership of the new group to Royal Dutch, and 40 percent to Shell. Both became holding companies for Bataafsche Petroleum Maatschappij, containing the production and refining assets, and Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company, containing the transport and storage assets.[27] National patriotic sensibilities would not permit a full-scale merger or takeover of either of the two companies.[27] The Dutch company, Koninklijke Nederlandsche Petroleum Maatschappij at The Hague, was in charge of production and manufacture.[28] The British Anglo-Saxon Petroleum Company was based in London, to direct the transport and storage of the products.[28][26]

In 1912, Royal Dutch Shell purchased the Rothschilds' Russian oil assets in a stock deal. The Group's production portfolio then consisted of 53 percent from the East Indies, 29 percent from the Russian Empire, and 17 percent from Romania.[26][29]

20th century

During the First World War, Shell was the main supplier of fuel to the British Expeditionary Force.[30] It was also the sole supplier of aviation fuel and supplied 80 percent of the British Army's TNT.[30] It also volunteered all of its shipping to the British Admiralty.[30]

The German invasion of Romania in 1916 saw 17% of the group's worldwide production destroyed.[30] In 1919, Shell took control of the Mexican Eagle Petroleum Company and in 1921 formed Shell-Mex Limited, which marketed products under the "Shell" and "Eagle" brands in the United Kingdom. During the Genoa Conference of 1922 Royal Dutch Shell was in negotiations for a monopoly over Soviet oilfields in Baku and Grosny, although the leak of a draft treaty led to breakdown of the talks.[31] In 1929, Shell Chemicals was founded.[30] By the end of the 1920s, Shell was the world's leading oil company, producing 11 percent of the world's crude oil supply and owning 10 percent of its tanker tonnage.[30]

Located in the north bank of the River Thames in London, Shell Mex House was completed in 1931, and was the head office for Shell's marketing activity worldwide.[30] In 1932, partly in response to the difficult economic conditions of the Great Depression, Shell-Mex merged its UK marketing operations with those of BP (British Petroleum) to create Shell-Mex & BP,[32] a company that traded until the brands separated in 1975. Royal Dutch Company ranked 79th among United States corporations in the value of World War II military production contracts.[33]

The 1930s saw Shell's Mexican assets seized by the local government.[30] After the invasion of the Netherlands by Nazi Germany in 1940, the head office of the Dutch companies was moved to Curaçao.[30] In 1945, Shell's Danish headquarters in Copenhagen, at the time being used by the Gestapo, was bombed by Royal Air Force De Havilland Mosquitoes in Operation Carthage.[34]

In 1937, Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), 23.75 percent owned by Royal Dutch Shell plc,[35] signed an oil concession agreement with the Sultan of Muscat. In 1952, IPC offered financial support to raise an armed force that would assist the Sultan in occupying the interior region of Oman, an area that geologists believed to be rich in oil. This led to the 1954 outbreak of the Jebel Akhdar War in Oman that lasted for more than 5 years.[36]

Around 1952, Shell was the first company to purchase and use a computer in the Netherlands.[37] The computer, a Ferranti Mark 1*, was assembled and used at the Shell laboratory in Amsterdam. In 1970, Shell acquired the mining company Billiton, which it subsequently sold in 1994.[38]

In the 1990s, protesters criticised the company's environmental record, particularly the possible pollution caused by the proposed disposal of the Brent Spar platform into the North Sea. Despite support from the UK government, Shell reversed the decision under public pressure but maintained that sinking the platform would have been environmentally better.[39] Shell subsequently published an unequivocal commitment to sustainable development, supported by executive speeches reinforcing this commitment.[40] Shell was subsequently criticised by the European Commission and five European Union members after deciding to leave part of its decommissioned oil rigs standing in the North Sea. Shell argued that removing them would be too costly and risky. Germany said that the estimated 11,000 tonnes of raw oil and toxins remaining in the rigs would eventually seep into the sea, and called it a 'ticking timebomb'.[41]

On 15 January 1999, off the Argentina town of Magdalena, Buenos Aires, the Shell tanker Estrella pampeana collided with a German cargo ship, emptying its contents into the lake, polluting the environment, drinkable water, plants and animals. Over a decade after the spill, a referendum held in Magdalena determined the acceptance of a US$9.5 million compensatory payout from Shell.[42] Shell denied responsibility for the spill, but an Argentine court ruled in 2002 that the corporation was responsible.[43]

21st century

In 2002, Shell acquired Pennzoil-Quaker State through its American division for $22 USD per share, or about $1.8 billion USD. Through its acquisition of Pennzoil, Shell became a descendant of Standard Oil. With its acquisition, Shell inherited multiple auto part brands including Jiffy Lube, Rain-X, and Fix-a-Flat. The company was notably late in its acquisition as seen by journalists, with Shell seen as streamlining its assets around the same time of other major mergers and acquisitions in the industry, such as BP's purchase of Amoco and the merger of Exxon and Mobil.[44]

In 2004, Shell overstated its oil reserves, resulting in loss of confidence in the group, a £17 million fine by the Financial Services Authority and the departure of the chairman Philip Watts. A lawsuit resulted in the payment of $450 million to non-American shareholders in 2007.[45][46][47]

As a result of the scandal, the corporate structure was simplified. Two classes of ordinary shares, A (code RDSA) and B (code RDSB), identical but for the tax treatment of dividends, were issued for the company.[48]

In November 2004, following a period of turmoil caused by the revelation that Shell had been overstating its oil reserves, it was announced that the Shell Group would move to a single capital structure, creating a new parent company to be named Royal Dutch Shell plc, with its primary listing on the LSE, a secondary listing on Euronext Amsterdam, its headquarters and tax residency in The Hague, Netherlands and its registered office in London. The company was already incorporated in 2002 as Forthdeal Limited, a shelf corporation incorporated by Swift Incorporations Limited and Instant Companies Limited, both based in Bristol.[19] The unification was completed on 20 July 2005 and the original owners delisted their companies from the respective exchanges. On 20 July 2005, the Shell Transport & Trading Company plc was delisted from the LSE,[49] whereas, Royal Dutch Petroleum Company from the New York Stock Exchange on 18 November 2005.[50] The shares of the company were issued at a 60/40 advantage for the shareholders of Royal Dutch in line with the original ownership of the Shell Group.[51]

During the 2009 Iraqi oil services contracts tender, a consortium led by Shell (45%) and which included Petronas (30%) was awarded a production contract for the "Majnoon field" in the south of Iraq, which contains an estimated 12.6 billion barrels (2.00×109 m3) of oil.[52][53] The "West Qurna 1 field" production contract was awarded to a consortium led by ExxonMobil (60%) and included Shell (15%).[54]

In February 2010, Shell and Cosan formed a 50:50 joint-venture, Raízen, comprising all of Cosan's Brazilian ethanol, energy generation, fuel distribution and sugar activities, and all of Shell's Brazilian retail fuel and aviation distribution businesses.[55] In March 2010, Shell announced the sale of some of its assets, including its liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) business, to meet the cost of a planned $28bn capital spending programme. Shell invited buyers to submit indicative bids, due by 22 March, with a plan to raise $2–3bn from the sale.[56] In June 2010, Shell agreed to acquire all the business of East Resources for a cash consideration of $4.7 billion. The transaction included East Resources' tight gas fields.[57]

Over the course of 2013, the corporation began the sale of its US shale gas assets and canceled a US$20 billion gas project that was to be constructed in the US state of Louisiana. A new CEO Ben van Beurden was appointed in January 2014, prior to the announcement that the corporation's overall performance in 2013 was 38 percent lower than in 2012—the value of Shell's shares fell by 3 percent as a result.[58] Following the sale of the majority of its Australia n assets in February 2014, the corporation plans to sell a further US$15 billion worth of assets in the period leading up to 2015, with deals announced in Australia, Brazil and Italy.[59]

Shell announced on 8 April 2015 it had agreed to buy BG Group for £47 billion (US$70 billion), subject to shareholder and regulatory approval.[60] The acquisition was completed in February 2016, resulting in Shell surpassing Chevron Corporation and becoming the world's second largest non-state oil company.[61]

On 7 June 2016, Shell announced that it would build an ethane cracker plant near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, after spending several years doing an environmental cleanup of the proposed plant's site.[62]

In January 2017, Shell agreed to sell £2.46bn worth of North Sea assets to oil exploration firm Chrysaor.[63] In 2017, Shell sold its oil sands assets to Canadian Natural Resources in exchange of approximately 8.8% stake in that company. In May 2017, it was reported that Shell plans to sell its shares in Canadian Natural Resources fully exiting the oil sands business.[64]

On 5 November 2017, the Paradise Papers, a set of confidential electronic documents relating to offshore investment, revealed that Argentine Energy Minister Juan José Aranguren was revealed to have managed the offshore companies 'Shell Western Supply and Trading Limited' and 'Sol Antilles y Guianas Limited', both subsidiaries of Shell. One is the main bidder for the purchase of diesel oil by the government through the state owned CAMMESA (Compañía Administradora del Mercado Mayorista Eléctrico).[65]

On 30 April 2020, Shell announced that it would cut its dividend for the first time since the Second World War, due to the oil price collapse following the reduction in oil demand during the COVID-19 pandemic. Shell stated that their net income adjusted for the cost of supply dropped to US$2.9 billion in three months to 31 March. This compared with US$5.3 billion in the same period the previous year.[66] On 30 September 2020, the company said that it would cut up to 9,000 jobs as a result of the economic effects caused by the pandemic and announced a "broad restructuring".[67] In December 2020, Shell forecast another write-down of $3.5-4.5 billion for the fourth quarter due to lower oil prices, following $16.8 billion of impairment in the second quarter.[68]

In February 2021, Shell announced a loss of $21.7 billion in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic,[69] despite reducing its operating expenses by 12%, or $4.5 billion, according to a Morningstar analysis cited by Barron's.[70][71]

In November 2021, Shell announced that it is planning to relocate their headquarters to London, abandon its dual share structure, and change its name from Royal Dutch Shell plc to Shell plc.[72] The company's name change was registered in the Companies House on 21 January 2022.[19]

In December 2021, Shell pulled out of the Cambo oil field, off the Shetland Islands, claiming that "the economic case for investment in this project is not strong enough at this time, as well as having the potential for delays". The proposed oilfield had been the subject of intense campaigning by environmentalists in the run-up to the COP26 UN climate summit in Glasgow in November 2021.[73]

On 4 March 2022, during the Russian invasion of Ukraine and in the midst of the growing boycott of Russian economy and related divestments, Shell bought a cargo of discounted Russian crude oil.[74] The next day, following criticism from Ukraine's Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba, Shell defended the purchase as a short term necessity, but also announced that it intended to reduce such purchases, and it would put profits from any Russian oil it purchases into a fund that would go towards humanitarian aid to Ukraine.[75] On 8 March, Shell announced that it would stop buying Russian oil and gas and close its service stations in the country.[76]

In 2022, the major oil and gas companies, including Shell,[77] reported sharp rises in interim revenues and profits.[78] In fact, this rise in profit for Shell was so sharp, that 2022 was the company's best year, as Shell recorded double the profits from 2021, and the highest profit in its entire history.[79]

Corporate affairs

Management

On 4 August 2005, the board of directors announced the appointment of Jorma Ollila, chairman and CEO of Nokia at the time, to succeed Aad Jacobs as the company's non-executive chairman on 1 June 2006. Ollila is the first Shell chairman to be neither Dutch nor British. Other non-executive directors include Maarten van den Bergh, Wim Kok, Nina Henderson, Lord Kerr, Adelbert van Roxe, and Christine Morin-Postel.[80]

Since 3 January 2014, Ben van Beurden has been CEO of Shell.[58] His predecessor was Peter Voser who became CEO of Shell on 1 July 2009.[81]

Following a career at the corporation, in locations such as Australia and Africa, Ann Pickard was appointed as the executive vice president of the Arctic at Royal Dutch Shell, a role that was publicized in an interview with McKinsey & Company in June 2014.[82]

In January 2023, Wael Sawan succeeded Ben van Beurden as CEO.[83]

Historical leadership

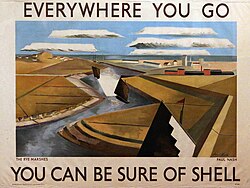

Name and logo

The name Shell is linked to The "Shell" Transport and Trading Company.[84] In 1833, the founder's father, Marcus Samuel Sr., founded an import business to sell seashells to London collectors. When collecting seashell specimens in the Caspian Sea area in 1892, the younger Samuel realised there was potential in exporting lamp oil from the region and commissioned the world's first purpose-built oil tanker, the Murex (Latin for a type of snail shell), to enter this market; by 1907 the company had a fleet. Although for several decades the company had a refinery at Shell Haven on the Thames, there is no evidence of this having provided the name.[85]

The Shell logo is one of the most familiar commercial symbols in the world. This logo is known as the "pecten" after the sea shell Pecten maximus (the giant scallop), on which its design is based. The yellow and red colours used are thought[86] to relate to the colours of the flag of Spain, as Shell built early service stations in California , previously a Spanish colony. The current revision of the logo was designed by Raymond Loewy in 1971.[87]

The slash was removed from the name "Royal Dutch/Shell" in 2005, concurrent with moves to merge the two legally separate companies (Royal Dutch and Shell) to the single legal entity which exists today.[88]

On 15 November 2021, Royal Dutch Shell plc announced plans to change its name to Shell plc.[89]

Logo evolution

-

1900–04

-

1904–09

-

1909–30

-

1930–48

-

1948–55

-

1955–70

-

1971–present

Operations

Business groupings

Shell is organised into four major business groupings:[90]

- Upstream – manages the upstream business. It searches for and recovers crude oil and natural gas and operates the upstream and midstream infrastructure necessary to deliver oil and gas to the market. Its activities are organised primarily within geographic units, although there are some activities that are managed across the business or provided through support units.

- Integrated Gas and New Energies – manages to liquefy natural gas, converting gas to liquids and low-carbon opportunities.

- Downstream – manages Shell's manufacturing, distribution, and marketing activities for oil products and chemicals. Manufacturing and supply include refinery, supply, and shipping of crude oil.

- Projects and technology – manages the delivery of Shell's major projects, provides technical services and technology capability covering both upstream and downstream activities. It is also responsible for providing functional leadership across Shell in the areas of health, safety and environment, and contracting and procurement.

Oil and gas activities

Shell's primary business is the management of a vertically integrated oil company. The development of technical and commercial expertise in all stages of this vertical integration, from the initial search for oil (exploration) through its harvesting (production), transportation, refining and finally trading and marketing established the core competencies on which the company was founded. Similar competencies were required for natural gas, which has become one of the most important businesses in which Shell is involved, and which contributes a significant proportion of the company's profits. While the vertically integrated business model provided significant economies of scale and barriers to entry, each business now seeks to be a self-supporting unit without subsidies from other parts of the company.[91]

Traditionally, Shell was a heavily decentralised business worldwide (especially in the downstream) with companies in over 100 countries, each of which operated with a high degree of independence. The upstream tended to be far more centralised with much of the technical and financial direction coming from the central offices in The Hague. The upstream oil sector is also commonly known as the "exploration and production" sector.[92]

Downstream operations, which now also includes the chemicals business, generate the majority of Shell's profits worldwide and is known for its global network of more than 40,000 petrol stations and its various oil refineries. The downstream business, which in some countries also included oil refining, generally included a retail petrol station network, lubricants manufacture and marketing, industrial fuel and lubricants sales, and a host of other product/market sectors such as LPG and bitumen. The practice in Shell was that these businesses were essentially local and that they were best managed by local "operating companies" – often with middle and senior management reinforced by expatriates.[93]

Sponsorships

Shell has a long history of motorsport sponsorship, most notably Scuderia Ferrari (1951–1964, 1966–1973 and 1996-present), BRM (1962–1966 and 1968–1972), Scuderia Toro Rosso (2007–2013 and 2016), McLaren (1967–1968 and 1984–1994), Lotus (1968–1971), Ducati Corse (since 1999), Team Penske (2011–present), Hyundai Motorsport (since 2005), AF Corse, Risi Competizione, BMW Motorsport (2015–present with also Pennzoil) and Dick Johnson Racing (1987-2004 and 2017–present).[94]

Starting in 2023, Shell became the official fuel for IndyCar Series, supplying E100 race fuel for all teams.[95]

Operations by region

Arctic

Kulluk oil rig

Following the purchase of an offshore lease in 2005, Shell initiated its US$4.5 billion Arctic drilling program in 2006, after the corporation purchased the "Kulluk" oil rig and leased the Noble Discoverer drillship.[96][97] At inception, the project was led by Pete Slaiby, a Shell executive who had previously worked in the North Sea.[98] However, after the purchase of a second offshore lease in 2008, Shell only commenced drilling work in 2012, due to the refurbishment of rigs, permit delays from the relevant authorities and lawsuits.[99][100][101] The plans to drill in the Arctic led to protests from environmental groups, particularly Greenpeace; furthermore, analysts in the energy field, as well as related industries, also expressed skepticism due to perceptions that drilling in the region is "too dangerous because of harsh conditions and remote locations".[101][102]

Further problems hampered the Arctic project after the commencement of drilling in 2012, as Shell dealt with a series of issues that involved air permits, Coast Guard certification of a marine vessel, and severe damage to essential oil-spill equipment. Additionally, difficult weather conditions resulted in the delay of drilling during mid-2012 and the already dire situation was exacerbated by the "Kulluk" incident at the end of the year. Shell had invested nearly US$5 billion by this stage of the project.[98][101]

As the Kulluk oil rig was being towed to the American state of Washington (state) to be serviced in preparation for the 2013 drilling season, a winter storm on 27 December 2012 caused the towing crews, as well as the rescue service, to lose control of the rig. As of 1 January 2013, the Kulluk was grounded off the coast Sitkalidak Island, near the eastern end of Kodiak Island. Following the accident, a Fortune magazine contacted Larry McKinney, the executive director at the Harte Research Institute for Gulf of Mexico Studies at Texas A&M, and he explained that "A two-month delay in the Arctic is not a two-month delay ... A two-month delay could wipe out the entire drilling season."[98]

It was unclear if Shell would recommence drilling in mid-2013, following the "Kulluk" incident, and, in February 2013, the corporation stated that it would "pause" its closely watched drilling project off the Alaskan coast in 2013, and will instead prepare for future exploration.[103] In January 2014, the corporation announced the extension of the suspension of its drilling program in the Arctic, with chief executive van Beurden explaining that the project is "under review" due to both market and internal issues.[104]

A June 2014 interview with Pickard indicated that, following a forensic analysis of the problems encountered in 2012, Shell will continue with the project and Pickard stated that she perceives the future of the corporation activity in the Arctic region as a long-term "marathon".[82] Pickard stated that the forensic "look back" revealed "there was an on/off switch" and further explained:

In other words, don't spend the money unless you're sure you're going to have the legal environment to go forward. Don't spend the money unless you're sure you're going to have the permit. No, I can't tell you that I'm going to have that permit until June, but we need to plan like we're going to have that permit in June. And so probably the biggest lesson is to make sure we could smooth out the on/off switches wherever we could and take control of our own destiny.[82]

Based upon the interview with Pickard, Shell is approaching the project as an investment that will reap energy resources with a lifespan of around 30 years.[82]

According to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management report in 2015 the chances of a major spill in a deep-sea Arctic drilling is 75% before century's end.[105]

Kodiak Island

In 2010, Greenpeace activists painted "No Arctic Drilling" using spilled BP oil on the side of a ship in the Gulf of Mexico that was en route to explore for Arctic oil for Shell. At the protest, Phil Radford of Greenpeace called for "President Obama [to] ban all offshore oil drilling and call for an end to the use of oil in our cars by 2030."[102]

On 16 March 2012, 52 Greenpeace activists from five different countries boarded Fennica and Nordica, multipurpose icebreakers chartered to support Shell's drilling rigs near Alaska.[106] Around the same time period, a reporter for Fortune magazine spoke with Edward Itta, an Inupiat leader and the former mayor of the North Slope Borough, who expressed that he was conflicted about Shell's plans in the Arctic, as he was concerned that an oil spill could destroy the Inupiat peoples hunting-and-fishing culture, but his borough also received major tax revenue from oil and gas production; additionally, further revenue from energy activity was considered crucial to the future of the living standard in Itta's community.[98]

In July 2012, Greenpeace activists shut down 53 Shell petrol stations in Edinburgh and London in a protest against the company's plans to drill for oil in the Arctic. Greenpeace's "Save the Arctic" campaign aims to prevent oil drilling and industrial fishing in the Arctic by declaring the uninhabited area around the North Pole a global sanctuary.[107]

A review was announced after the Kulluk oil rig ran aground near Kodiak Island in December 2012.[108]

In response, Shell filed lawsuits to seek injunctions from possible protests, and Benjamin Jealous of the NAACP and Radford argued that the legal action was "trampling Americans' rights."[109] According to Greenpeace, Shell lodged a request with Google to take down video footage of a Greenpeace protest action that occurred at the Shell-sponsored Formula One (F1) Belgian Grand Prix on 25 August 2013, in which "SaveTheArctic.org" banners appear at the winners' podium ceremony. In the video, the banners rise up automatically—activists controlled their appearance with the use of four radio car antennas—revealing the website URL, alongside an image that consists of half of a polar bear's head and half of the Shell logo.[110]

Shell then announced a "pause" in the timeline of the project in early 2013[103] and, in September 2015, the corporation announced the extension of the suspension of its drilling program in the Arctic.[111]

Polar Pioneer rig

A June 2014 interview with the corporation's new executive vice president of the Arctic indicated that Shell will continue with its activity in the region.[82][104]

In Seattle protests began in May 2015 in response to the news that the Port of Seattle made an agreement with Shell to berth rigs at the Port's Terminal 5 during the off-season of oil exploration in Alaskan waters. The arrival of Shell's new Arctic drilling vessel, Polar Pioneer (IMO number: 8754140), a semi-submersible offshore drilling rig, was greeted by large numbers of environmental protesters paddling kayaks in Elliott Bay.[112][113]

On 6 May 2015, it was reported that during a coast guard inspection of Polar Pioneer, a piece of anti-pollution gear failed, resulting in fines and delay of the operation.[114] Oil executives from Total and Eni interviewed by the The New York Times , expressed scepticism about Shell's new ambitions for offshore drilling in the Arctic, and cited economic and environmental hurdles. ConocoPhillips and Equinor (formerly Statoil) suspended Arctic drilling earlier, after Shell's failed attempt in 2012.[115]

Australia

On 20 May 2011, Shell's final investment decision for the world's first floating liquefied natural gas (FLNG) facility was finalized following the discovery of the remote offshore Prelude field—located off Australia's northwestern coast and estimated to contain about 3 trillion cubic feet of natural gas equivalent reserves—in 2007. FLNG technology is based on liquefied natural gas (LNG) developments that were pioneered in the mid-20th century and facilitates the exploitation of untapped natural gas reserves located in remote areas, often too small to extract any other way.[116][117]

The floating vessel to be used for the Prelude field, known as Prelude FLNG, is promoted as the longest floating structure in the world and will take in the equivalent of 110,000 barrels of oil per day in natural gas—at a location 200 km (125 miles) off the coast of Western Australia—and cool it into liquefied natural gas for transport and sale in Asia. The Prelude is expected to start producing LNG in 2017[118]—analysts estimated the total cost of construction at more than US$12 billion.[116][117][119]

Following the decision by the Shell fuel corporation to close its Geelong Oil Refinery in Australia in April 2013, a third consecutive annual loss was recorded for Shell's Australian refining and fuel marketing assets. Revealed in June 2013, the writedown is worth A$203 million and was preceded by a A$638m writedown in 2012 and a A$407m writedown in 2011, after the closure of the Clyde Refinery in Sydney, Australia.[120]

In February 2014, Shell sold its Australian refinery and petrol stations for US$2.6 billion (A$2.9 billion) to Swiss company Vitol.[121]

At the time of the downstream sale to Vitol, Shell was expected to continue investment into Australian upstream projects, with projects that involve Chevron Corp., Woodside Petroleum and Prelude.[59] In June 2014, Shell sold 9.5% of its 23.1% stake in Woodside Petroleum and advised that it had reached an agreement for Woodside to buy back 9.5% of its shares at a later stage. Shell became a major shareholder in Woodside after a 2001 takeover attempt was blocked by then federal Treasurer Peter Costello and the corporation has been open about its intention to sell its stake in Woodside as part of its target to shed assets. At a general body meeting, held on 1 August 2014, 72 percent of shareholders voted to approve the buy-back, short of the 75 percent vote that was required for approval. A statement from Shell read: "Royal Dutch Shell acknowledges the outcome of Woodside Petroleum Limited's shareholders' negative vote on the selective buy-back proposal. Shell is reviewing its options in relation to its remaining 13.6 percent holding."[122]

Brunei

Brunei Shell Petroleum (BSP) is a joint venture between the Government of Brunei and Shell.[123] The British Malayan Petroleum Company (BMPC), owned by Royal Dutch Shell, first found commercial amounts of oil in 1929.[124] It currently produces 350,000 barrels of oil and gas equivalent per day.[125] BSP is the largest oil and gas company in Brunei, a sector which contributes 90% of government revenue.[126] In 1954, the BMPC in Seria had a total of 1,277 European and Asian staff.[127]

China

The company has upstream operations in unconventional oil and gas in China. Shell has a joint venture with PetroChina at the Changbei tight gas field in Shaanxi, which has produced natural gas since 2008. The company has also invested in exploring for shale oil in Sichuan.[128] The other unconventional resource which Shell invested in in China was shale. The company was an early entrant in shale oil exploration in China but scaled down operations in 2014 due to difficulties with geology and population density.[129] It has a joint venture to explore for oil shale in Jilin through a joint venture with Jilin Guangzheng Mineral Development Company Limited.[130]

Hong Kong

Shell has been active in Hong Kong for a century, providing Retail, LPG, Commercial Fuel, Lubricants, Bitumen, Aviation, Marine and Chemicals services, and products. Shell also sponsored the first Hong Kong-built aircraft, Inspiration, for its around-the-world trip.[131]

India

Shell India has inaugurated its new lubricants laboratory at its Technology Centre in Bangalore.[132]

Ireland

Shell first started trading in Ireland in 1902.[133] Shell E&P Ireland (SEPIL) (previously Enterprise Energy Ireland) is an Irish exploration and production subsidiary of Royal Dutch Shell. Its headquarters are on Leeson Street in Dublin. It was acquired in May 2002.[134] Its main project is the Corrib gas project, a large gas field off the northwest coast, for which Shell has encountered controversy and protests in relation to the onshore pipeline and licence terms.[135]

In 2005, Shell disposed of its entire retail and commercial fuels business in Ireland to Topaz Energy Group. This included depots, company-owned petrol stations and supply agreements stations throughout the island of Ireland.[136] The retail outlets were re-branded as Topaz in 2008/9.[137]

The Topaz fuel network was subsequently acquired in 2015 by Couchetard[138] and these stations began re-branding to Circle K in 2018.[139]

Malaysia

Shell discovered the first oil well in Borneo in 1910, in Miri, Sarawak. Today, the oil well is a state monument known as the Grand Old Lady. In 1914, following this discovery, Shell built Borneo's first oil refinery and laid a submarine pipeline in Miri.[140][141]

Nigeria

Shell began production in Nigeria in 1958.[142] In Nigeria, Shell told US diplomats that it had placed staff in all the main ministries of the government.[143] Shell continues however upstream activities/extracting crude oil in the oil-rich Niger Delta as well as downstream/commercial activities in South Africa . In June 2013, the company announced a strategic review of its operations in Nigeria, hinting that assets could be divested.[144][145] In August 2014, the company disclosed it was in the process of finalizing the sale of its interests in four Nigerian oil fields.[146] On 29 January 2021 a Dutch court ruled that Shell was responsible for multiple oil leaks in Nigeria.[147]

The actions of companies like Shell has led to extreme environmental issues in the Niger Delta. Many pipelines in the Niger Delta owned by Shell are old and corroded. Shell has acknowledged its responsibility for keeping the pipelines new but has also denied responsibility for environmental causes.[148] The heavy contamination of the air, ground and water with toxic pollutants by the oil industry in the Niger Delta is often used as an example of ecocide.[149][150][151][152] This has led to mass protests from the Niger Delta inhabitants, Amnesty International, and Friends of the Earth the Netherlands against Shell. It has also led to action plans to boycott Shell by environmental and human rights groups.[153] In January 2013, a Dutch court rejected four out of five allegations brought against the firm over oil pollution in the Niger Delta but found a subsidiary guilty of one case of pollution, ordering compensation to be paid to a Nigerian farmer.[154]

Nordic countries

On 27 August 2007, Shell and Reitan Group, the owner of the 7-Eleven brand in Scandinavia, announced an agreement to re-brand some 269 service stations across Norway , Sweden, Finland and Denmark , subject to obtaining regulatory approvals under the different competition laws in each country.[155] In April 2010 Shell announced that the corporation is in process of trying to find a potential buyer for all of its operations in Finland and is doing similar market research concerning Swedish operations.[156][157] In October 2010 Shell's gas stations and the heavy vehicle fuel supply networks in Finland and Sweden, along with a refinery located in Gothenburg, Sweden were sold to St1, a Finnish energy company, more precisely to its major shareholding parent company Keele Oy.[158]

North America

Through most of Shell's early history, Shell USA business in the United States was substantially independent. Its stock was traded on the NYSE, and the group's central office had little direct involvement in running the operation. However, in 1984, Shell made a bid to purchase those shares of Shell Oil Company it did not own (around 30%) and, despite opposition from some minority shareholders which led to a court case, Shell completed the buyout for a sum of $5.7 billion.[159]

Philippines

Royal Dutch Shell operates in the Philippines under its subsidiary, Pilipinas Shell Petroleum Corporation or PSPC. Its headquarters is in Makati and it has facilities in the Pandacan oil depot and other key locations.[160]

In January 2010, the Bureau of Customs claimed 7.34 billion pesos worth of unpaid excise taxes against Pilipinas Shell for importing Catalytic cracked gasoline (CCG) and light catalytic cracked gasoline (LCCG) stating that those imports are bound for tariff charges.[161]

In August 2016, Pilipinas Shell filed an application to sell US$629 million worth of primary and secondary shares to the investing public (registration statement) with the SEC. This was a prelude to filing its IPO listing application with the Philippine Stock Exchange. On 3 November 2016 the Pilipinas Shell Petroleum Corporation was officially listed on the Philippine Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol SHLPH after they held its initial public offering on 19 to 25 October of the same year.[162]

Due to the economic slowdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on the global, regional and local economies, continually low refining margins, and competition with imported refined products, the management of Pilipinas Shell announced in August 2020 that the 110,000 bbl/d refinery in Tabangao, Batangas, which started operations in 1962, will be shutting down permanently and turned into an import terminal instead.[163]

Russia

In February 2022, Shell exited all its joint ventures with Gazprom because of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine[164] and, in March 2022, Shell announced that it would stop buying oil from Russia and close all its service stations there.[165] In April 2022, it emerged that Shell was to book up to $5 billion in impairment charges from exiting its interests in Russia.[166]

Singapore

Singapore is the main centre for Shell's petrochemical operations in the Asia Pacific region. Shell Eastern Petroleum limited (SEPL) have their refinery located in Singapore's Pulau Bukom island. They also operate as Shell Chemicals Seraya in Jurong Island.[167] In November 2020, Shell announced that, as part of efforts to curtail pollution emissions, it will cut its oil-processing capacity in Singapore.[168]

United Kingdom

In the UK sector of the North Sea Shell employs around 4,500 staff in Scotland as well as an additional 1,000 service contractors: however in August 2014 it announced it was laying off 250 of them, mainly in Aberdeen.[169] Shell paid no UK taxes on its North Sea operations over the period 2018 to 2021.[170]

Alternative energy

In the early 2000s Shell moved into alternative energy and there is now an embryonic "Renewables" business that has made investments in solar power, wind power, hydrogen, and forestry. The forestry business went the way of nuclear, coal, metals and electricity generation, and was disposed of in 2003. In 2006 Shell paid SolarWorld to take over its entire solar business[171] and in 2008, the company withdrew from the London Array which when built was the world's largest offshore wind farm.[172]

Shell also is involved in large-scale hydrogen projects. HydrogenForecast.com describes Shell's approach thus far as consisting of "baby steps", but with an underlying message of "extreme optimism".[173] In 2015, the company announced plans to install hydrogen fuel pumps across Germany, planning on having 400 locations in operation by 2023.[174]

Shell holds 44% of Raízen, a joint venture with Brazilian sugarcane producer Cosan which is the third-largest Brazil-based energy company by revenues and a major producer of ethanol.[16] In 2015, the company partnered with Brazilian start-up company Insolar to install solar panels in Rio de Janeiro to deliver electricity to the Santa Marta neighbourhood.[175]

Shell is the operator and major shareholder of The Shell Canada Quest Energy project, based within the Athabasca Oil Sands Project, located near Fort McMurray, Alberta.[176] It holds a 60% share, alongside Chevron Canada Limited, which holds 20%, and Marathon Canadian Oil Sands Holding Limited, which holds the final 20%.[177] Commercial operations launched in November 2015. It was the world's first commercial-scale oil and sand carbon capture storage (CCS) project.[176] It is expected to reduce CO2 emissions in Canada by 1.08 million tonnes per year.[178]

In December 2016, Shell won the auction for the 700 MW Borssele III & IV offshore wind farms at a price of 5.45 c/kWh, beating 6 other consortia.[179] In June 2018, it was announced that the company and its co-investor Partners Group had secured $1.5bn for the project, which also involves Eneco, Van Oord, and Mitsubishi/DGE.[180]

In October 2017, it bought Europe's biggest vehicle charging network, "NewMotion."[181]

In November 2017, Shell's CEO Ben van Beurden announced Shell's plan to cut half of its carbon emissions by 2050, and 20 percent by 2035. In this regard, Shell promised to spend $2 billion annually on renewable energy sources. Shell began to develop its wind energy segment in 2001, the company now operates six wind farms in the United States and is part of a plan to build two offshore wind farms in the Netherlands.[182]

In December 2017, the company announced plans to buy UK household energy and broadband provider First Utility.[183] In March 2019 it rebranded to Shell Energy and announced that all electricity would be supplied from renewable sources.[184]

In December 2018, the company announced that it had partnered with SkyNRG to begin supplying sustainable aviation fuel to airlines operating out of San Francisco Airport (SFO), including KLM, SAS, and Finnair.[185][186] In the same month, the company announced plans to double its renewable energy budget to investment in low-carbon energy to $4 billion US each year, with an aim to spend up to $2 billion US on renewable energy by 2021.[187]

In January 2018, the company acquired a 44% interest in Silicon Ranch, a solar energy company run by Matt Kisber, as part of its global New Energies project.[188] The company took over from Partners Group, paying up to an estimated $217 million for the minority interest.[189]

In February 2019, the company acquired German solar battery company Sonnen.[190] It first invested in the company in May 2018 as part of its New Energies project.[191] As of late 2021, the company had 800 employees and has installed 70.000 home battery systems.[192]

On 27 February 2019, the company acquired British VPP operator Limejump for an undisclosed amount.[193]

In July 2019, Shell installed their first 150 kW electric car chargers at its London petrol stations with payments handled via SMOOV. They also plan to provide 350 kW chargers in Europe by entering into an agreement with IONITY.[194]

On 26 January 2021, Shell said it would buy 100 per cent of Ubitricity, owner of the largest public charging network for electric vehicles in the United Kingdom, as the company expands its presence along the power supply chain.[195]

On 25 February 2021, Shell announced the acquisition of German Virtual Power Plant (VPP) company Next Kraftwerke for an undisclosed amount. Next Kraftwerke connects renewable electricity generation- and storage projects to optimize the usage of those assets. The company mostly operates in Europe.[196]

In November 2022, it was announced Shell's wholly-owned subsidiary, Shell Petroleum NV, had acquired the Odense-headquartered renewable natural gas producer, Nature Energy Biogas A/S for nearly $2 billion USD.[197]

Controversies

General issues

Shell's public rhetoric and pledges emphasize that the company is shifting towards climate-friendly, low-carbon and transition strategies.[198] However, a 2022 study found that the company's spending on clean energy was insignificant and opaque, with little to suggest that the company's discourse matched its actions.[198]

In 1989, Shell redesigned a $3-billion natural gas platform in the North Sea, raising its height one to two meters, to accommodate an anticipated sea level rise due to global warming.[199] In 2013, Royal Dutch Shell PLC reported CO

2 emissions of 81 million metric tonnes.[200]

In 2017, Shell sold non-compliant foreign fuel to consumers.[201]

In 2020, the Northern Lights CCS project was announced, which is a joint project between Equinor, Shell and Total, operating in the European Union (Norway) and aiming to store liquid CO

2 beneath the seabed.[202][203][204][205]

Environmentalists have expressed concern that Shell is processing oil from the Amazon region of South America. In the United States, the Martinez refinery (CA) and the Puget Sound Refinery (WA) carry Amazonian oil. In 2015, 14% of the Martinez refinery's gross, at 19,570 barrels per day, came from the Amazon.[206]

In 2021, Shell was ranked as the 10th most environmentally responsible company out of 120 oil, gas, and mining companies involved in resource extraction north of the Arctic Circle in the Arctic Environmental Responsibility Index (AERI).[207]

In December 2021, Royal Dutch Shell decided to move ahead with seismic tests to explore for oil in humpback whale breeding grounds along South Africa's eastern coastline.[208] On 3 December 2021, a South African high court struck down an urgent application brought by environmentalists to stop the project, which will involve a vessel regularly firing an air gun that produces a very powerful shock wave underwater to help map subsea geology. According to Greenpeace Africa and the South African Deep Sea Angling Association, this could cause "irreparable harm" to the marine environment, especially to migrating humpback whales in the area.[209]

Climate change

In 2017, a public information film ("Climate of Concern") unseen for years resurfaced and showed Shell had clear grasp of global warming 26 years earlier but has not acted accordingly since, said critics.[210][211][212]

The burning of the fossil fuels produced by Shell are responsible for 1.67% of global industrial greenhouse gas emissions from 1988 to 2015.[213] In April 2020, Shell announced plans to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or sooner.[214] However, internal documents from the company released by the Democratic-led House committee reveal a private 2020 communication saying Shell does not have any plans to bring emissions to zero for next 10–20 years.[215]

Measured by both its own emissions, and the emissions of all the fossil fuels it sells, Shell was the ninth-largest corporate producer of greenhouse gas emissions in the period 1988–2015.[216]

Climate case

On 5 April 2019, Milieudefensie (Dutch for "environmental defense"), together with six NGOs and more than 17,000 citizens, sued Shell, accusing the company of harming the climate despite knowing about global warming since 1986.[217][218] In May 2021, the district court of The Hague ruled that Shell must reduce carbon dioxide emissions by 45% by 2030 (compared to 2019 levels).[219]

Oil spills

- Shell was responsible for around 21,000 gallons of oil spilled near Tracy, California, in May 2016 due to a pipeline crack.[220]

- Shell was responsible for an 88,200-gallon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico in May 2016.[221]

- Two ruptures in a Shell Oil Co. pipeline in Altamont, California – one in September 2015 and another in May 2016 – led to questions on whether the Office of the State Fire Marshal, charged with overseeing the pipeline, was doing an adequate job.[222]

- On 29 January 2021, a Dutch court ordered Royal Dutch Shell plc's Nigerian unit to compensate for oil spills in two villages over 13 years ago. Shell Nigeria is liable for damages from pipeline leaks in the villages of Oruma and Goi, the Hague Court of Appeals said in a ruling. Shell said that it should not be liable, as the spills were the result of sabotage.[223]

Accusations of greenwashing

On 2 September 2002, Shell Chairman Philip Watts accepted the "Greenwash Lifetime Achievement Award" from the Greenwash Academy's Oscar Green, near the World Summit on Sustainable Development.[224]

In 2007, British ASA ruled against a Shell ad involving chimneys spewing flowers, which depicted Shell's waste management policies, claiming it was misleading the public about Shell's environmental impact.[225][226]

In 2008, the British ASA ruled that Shell had misled the public in an advertisement when it claimed that a $10 billion oil sands project in Alberta, Canada , was a "sustainable energy source".[227][228]

In 2021, Netherlands officials told Shell to stop running a campaign which claimed customers could turn their fuel "carbon neutral" by buying offsets, as it was concluded that this claim was devoid of evidence.[229][230]

In December 2022, U.S. House Oversight and Reform Committee Chair Carolyn Maloney and U.S. House Oversight Environment Subcommittee Chair Ro Khanna sent a memorandum to all House Oversight and Reform Committee members summarizing additional findings from the Committee's investigation into the fossil fuel industry disinformation campaign to obscure the role of fossil fuels in causing global warming, and that upon reviewing internal company documents, accused Shell along with BP, Chevron Corporation, and ExxonMobil of greenwashing their Paris Agreement carbon neutrality pledges while continuing long-term investment in fossil fuel production and sales, for engaging in a campaign to promote the use of natural gas as a clean energy source and bridge fuel to renewable energy, and of intimidating journalists reporting about the companies' climate actions and of obstructing the Committee's investigation, which ExxonMobil, Shell, and the American Petroleum Institute denied.[231][232][233]

Health and safety

A number of incidents over the years led to criticism of Shell's health and safety record, including repeated warnings by the UK Health and Safety Executive about the poor state of the company's North Sea platforms.[234]

Reaction to the War in Ukraine

Shell already had previous experience exiting markets that were subject to sanctions pressure from NATO or EU member states. In particular, in 2013, Shell announced that it was suspending its operations in Syria.[235] On 8 March 2022, Shell announced its intention to phase out all Russian hydrocarbon production and acquisition projects, including crude oil, petroleum products, natural gas and liquefied natural gas (LNG). In early 2022, the company was criticized by the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine for its slow response to the war in Ukraine.[236] As of April 2023, Shell still had shares in Russian companies, such as 27.5% in Sakhalin Energy Investment Company (SEIC), a joint venture with Gazprom (50%), Mitsui (12.5%) and Mitsubishi (10%).[237]

royaldutchshellplc.com

This domain name was first registered by a former marketing manager for Royal Dutch Shell plc, Alfred Donovan, and has been used as a "gripe site".[238] It avoids being an illegal cybersquatter as long as it is non-commercial, active, and no attempt is made to sell the domain name, as determined by WIPO proceedings.[239] In 2005, Donovan said he would relinquish the site to Shell after it "gets rid of all the management he deems responsible for its various recent woes."[240] The site has been recognized by several media outlets for its role as an Internet leak. In 2008 the Financial Times published an article based on a letter published by royaldutchshellplc.com,[241] which Reuters and The Times also covered shortly thereafter.[242][243] On 18 October 2006, the site published an article stating that Shell had for some time been supplying information to the Russian government relating to Sakhalin II.[244] The Russian energy company Gazprom subsequently obtained a 50% stake in the Sakhalin-II project.[245] Other instances where the site has acted as an Internet leak include a 2007 IT outsourcing plan,[246] as well as a 2008 internal memo where CEO Jeroen van der Veer expressed disappointment in the company's share-price performance.[247]

The gripe site has also been recognized as a source of information regarding Shell by several news sources. In the 2006 Fortune Global 500 rankings, in which Royal Dutch Shell placed third, royaldutchshellplc.com was listed alongside shell.com as a source of information.[248] In 2007 the site was described as "a hub for activists and disgruntled former employees."[249] A 2009 article called royaldutchshellplc.com "the world's most effective adversarial Web site."[250] The site has been described as "an open wound for Shell."[244]

See also

- Bataafse Petroleum Maatschappij

- Chaco War

- Fossil fuels lobby

- Lensbury

- List of companies based in London

- Shell Guides, a series of guidebooks

- Shell V-Power

- Shell Service Station (Winston-Salem, North Carolina)

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "SHELL PLC overview - Find and update company information - GOV.UK" (in en). 2002-02-05. https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/04366849.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Annual Results 2022". Shell plc. https://www.shell.com/investors/results-and-reporting/quarterly-results/_jcr_content/root/main/section/simple_505013828/simple/text_1689406490.multi.stream/1675295770390/c4588bfb8b938904cc08e44fb874ae2891b6e70a/q4-2022-qra-document.pdf.

- ↑ "About us". Shell plc. https://www.shell.co.uk/about-us.html.

- ↑ "Modern Slavery Act Statement 2022". https://www.shell.com/uk-modern-slavery-act/_jcr_content/root/main/section/call_to_action/links/item0.stream/1678297669616/bc592f9f745abb7862b8395a156b54d2165eca47/shell-plc-modern-slavery-act-statement-2022.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Shell begins trading under simpler, single-line share structure". Reuters. 31 January 2022. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/shell-begin-trading-under-simpler-single-line-share-structure-2022-01-31/.

- ↑ "Global 500" (in en). https://fortune.com/global500/.

- ↑ Garavini, Giuliano (2019). The Rise and Fall of OPEC in the Twentieth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780198832836. https://books.google.com/books?id=_W6fDwAAQBAJ. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ↑ Peebles, Malcolm (1980). Evolution of the Gas Industry. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 194. ISBN 9781349051557. https://books.google.com/books?id=BFddDwAAQBAJ&q=shell+first+lng+cargo+1964.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Fox, Justin (8 April 2015). "Stop Calling Shell an Oil Company". Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2015-04-08/maybe-it-s-time-to-stop-calling-shell-an-oil-company.

- ↑ "Tax Contribution Report". Shell. 2020. https://reports.shell.com/tax-contribution-report/2020/_assets/downloads/shell-tax-contribution-report-2020.pdf.

- ↑ "Shell at a glance". Royal Dutch Shell plc. http://www.shell.com/home/content/aboutshell/at_a_glance/.

- ↑ "8 Apr 2015 – Recommended Cash and Share Offer Announcement". Royal Dutch Shell plc. http://www.shell.com/investors/pre-combination-bg-group-publications/recommended-cash-and-share-offer-for-bg-group-plc-by-royal-dutch-shell-plc/_jcr_content/par/textimage_931903780.stream/1447807511882/0d4c28106256a8fda81c66a7abeca10ab78288bd4407420d3ae8f385a8870849/offer-announcement-royaldutchshellplc-bggroupplc.pdf.

- ↑ "Shell Annual Report and Accounts 2019Annual Report and Accounts 2019". Royal Dutch Shell. https://reports.shell.com/annual-report/2019/servicepages/downloads/files/shell_annual_report_2019.pdf.

- ↑ "Exploration & Production in the United States". Royal Dutch Shell plc. http://www.shell.us/home/content/usa/aboutshell/shell_businesses/upstream/.

- ↑ "Shareholding Structure" (in en-US). https://ri.raizen.com.br/en/about-raizen/shareholding-structure/.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Shell and Cosan join forces for $ 12 billion ethanol venture - Renewable Energy - GREEN NEWS - ECOSEED Global Green News Portal". 8 September 2010. http://ecoseed.org/en/business/renewable-energy/article/95-renewable-energy/7903-shell-and-cosan-join-forces-for-$-12-billion-ethanol-venture.

- ↑ "Largest Companies by Market Cap" (in en-us). https://companiesmarketcap.com/.

- ↑ "Global 500" (in en). https://fortune.com/global500/2022/.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 "SHELL PLC overview - Find and update company information - GOV.UK". Companies House. https://find-and-update.company-information.service.gov.uk/company/04366849.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "The beginnings". shell.com. http://www.shell.com/global/aboutshell/who-we-are/our-history/the-beginnings.html.

- ↑ Fred Aftalion (2001). A History of the International Chemical Industry. Chemical Heritage Foundation. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-941901-29-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=zTP1MFJw8CsC&pg=PA142. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ↑ Merrillees 2015, p. 60.

- ↑ "Royal Dutch Shell: History". http://www.shell.com/home/content/aboutshell/who_we_are/our_history/dir_our_history_14112006.html.

- ↑ Mark Forsyth (2011). The Etymologicon: A Circular Stroll through the Hidden Connections of the English Language. Icon Books. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-84831-319-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=KUZxTvay3PMC. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ↑ Falola, Toyin; Genova, Ann (2005). The Politics of the Global Oil Industry: An Introduction. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 30. ISBN 9780275984007. https://books.google.com/books?id=BXWasJHiT-kC&q=marcus+samuel+sold+shells&pg=PA30. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Yergin, Daniel (1991). The Prize, The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 63–77,86–87,114–127. ISBN 9780671799328.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 F. C. Gerretson (1953). History of the Royal Dutch. Brill Archive. p. 346. GGKEY:NNJNHTLUZKG. https://books.google.com/books?id=IsoUAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA346. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 F. C. Gerretson (1953). History of the Royal Dutch. Brill Archive. p. 346. GGKEY:NNJNHTLUZKG.

- ↑ Yergin, Daniel (1991). The Prize, The Epic Quest for Oil, Money & Power. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 133. ISBN 9780671799328.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 30.7 30.8 "The early 20th century". shell.com. http://www.shell.com/global/aboutshell/who-we-are/our-history/early-20th-century.html.

- ↑ Steiner, Zara (2005). The lights that failed : European international history, 1919-1933. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-151881-2. OCLC 86068902. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/86068902. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ↑ Reference and contact details: GB 1566 SMBP Title:Shell-Mex and BP Archive Dates of Creation: 1900–1975 Held at: BP Archive GB 1566 SMBP

- ↑ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.619

- ↑ Velschow, Klaus. "The Bombing of the Shellhus on March 21, 1945". http://www.milhist.dk/besattelsen/shell/shell.html.

- ↑ "United States Office of the Historian: The 1928 Red Line Agreement". https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/red-line.

- ↑ Peterson, J. E. (2 January 2013). Oman's Insurgencies: The Sultanate's Struggle for Supremacy. Saqi. ISBN 9780863567025. https://books.google.com/books?id=wkUhBQAAQBAJ&q=moff%20oman&pg=PT43. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- ↑ The Ferranti Mark 1* that went to Shell labs in Amsterdam, Netherlands (Dutch only)

- ↑ "Analysis: Cash bounty lures miners into risky empire-building". Reuters. 27 September 2010. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mining-conglomerates-analysis-idUSTRE68Q2NH20100927?pageNumber=2.

- ↑ Brent Spar's long saga BBC News, 1998

- ↑ Ek Kia, Tan (19 April 2005). "Sustainable Development in Shell". http://www.shellchemicals.com/chemicals/pdf/speeches/sydney_speech_april_2005.pdf.

- ↑ "UK facing EU outrage over 'timebomb' of North Sea oil rigs". 4 September 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/sep/04/uk-facing-eu-outrage-over-timebomb-of-north-sea-oil-rigs.

- ↑ "Argentinian town agrees to damages for oil spill". Radio Netherlands Worldwide. 18 May 2009. http://www.rnw.nl/english/article/argentinian-town-agrees-damages-oil-spill.

- ↑ "Court rules Shell must spend US$35mn on Magdalena clean-up". BNamericas. 22 November 2002. http://www.bnamericas.com/news/oilandgas/Court_rules_Shell_must_spend_US*35mn_on_Magdalena_clean-up.

- ↑ "Shell Oil To Acquire Pennzoil". New York Times. 26 March 2002. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/03/26/business/shell-oil-to-acquire-pennzoil.html.

- ↑ G. Thomas Sims (12 April 2007). "Shell Settles With Europe on Overstated Oil Reserves". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/12/business/12shell.html.

- ↑ Jill Treanor (31 May 2009). "Royal Dutch Shell to compensate shareholders for reserves scandal". The Guardian (London). https://www.theguardian.com/business/2009/may/31/royal-dutch-shell-compensation-shareholders.

- ↑ Tim Fawcett (18 March 2004). "Shell's slippery slope". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/business/3524438.stm.

- ↑ Kennon, Joshua (9 July 2013). "Royal Dutch Shell Class A vs Class B Shares". https://www.joshuakennon.com/royal-dutch-shell-class-a-vs-class-b-shares/.

- ↑ The Shell Transport & Trading Company plc delisted from LSE

- ↑ "N.V. Koninklijke Nederlandsche Petroleum Maatschappij (English translation, Royal Dutch Petroleum Company) to Withdraw its Ordinary Shares, par value 0.56 Euro, from NYSE". https://www.sec.gov/rules/delist/1-03788_111805.pdf.

- ↑ Shell shareholders agree merger BBC News, 2005

- ↑ "Iraq holds oil auction, Shell wins giant field". Reuters. 11 December 2009. http://in.reuters.com/article/idINIndia-44646120091211.

- ↑ Pagnamenta, Robin (12 December 2009). "Shell secures vital toehold in 'the new Iraq' where oil is ready to flow". The Times (London). http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/industry_sectors/natural_resources/article6954091.ece.

- ↑ 2009 Iraqi oil services contracts tender

- ↑ "Shell bets on ethanol in $21 billion deal with Brazil's Cosan". Reuters. 1 February 2010. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-cosan-shell-idUSTRE6101TW20100201.

- ↑ "Shell to fund capital spending by selling LPG assets". 1 March 2010. http://www.newstatesman.com/energy-and-clean-tech/2010/03/lpg-business-gas-shell-capital.

- ↑ "Shell Acquires East Resources' Tight Gas Fields". Infogrok.com. 31 May 2010. http://www.infogrok.com/index.php/energy-companies/shell-acquires-east-resources-tight-gas-fields.html.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Tom Bawden (17 January 2014). "Royal Dutch Shell issues shock profit warning". The Independent (London). https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/royal-dutch-shell-issues-shock-profit-warning-9066193.html.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 James Paton (21 February 2014). "Vitol to Pay Shell A$2.9 Billion for Australian Assets". Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-02-20/vitol-to-pay-a-2-9-billion-for-shell-s-australian-gas-stations.html.

- ↑ Tiffany Hsu (8 April 2015). "Shell-BG tie-up could challenge market leader Exxon Mobil". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-royal-dutch-shell-bg-group-20150408-story.html.

- ↑ Rakteem Katakey (15 February 2016). "Shell Surpasses Chevron to Become No. 2 Oil Company: Chart". Bloomberg.com. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-02-15/shell-surpasses-chevron-to-become-no-2-oil-company-chart.

- ↑ Shell takes final investment decision to build a new petrochemicals complex in Pennsylvania, US Royal Dutch Shell (06/07/2016)

- ↑ "Shell sells North Sea assets worth £2.46bn to Chrysaor". BBC News. 31 January 2017. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-38807175.

- ↑ Williams, Nia (24 May 2017). "Shell, ConocoPhillips oil sands share selloff risks flooding market". Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-shell-divestiture-canada-analysis-idUSKBN18L014.

- ↑ "Aranguren: su paso por una offshore de Shell a la que el Estado le compró gasoil por US$ 150 M". Perfil. 7 November 2017. http://www.perfil.com/paradisepapers/paradise-papers-aranguren-su-paso-por-una-offshore-de-shell-a-la-que-el-estado-le-compro-gasoil-por-us-150-m.phtml.

- ↑ Raval, Anjli (30 April 2020). "Shell cuts dividend for first time since second world war". Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/9e9419b9-63d7-4671-9dd5-527b57434777.

- ↑ McFarlane, Sarah (30 September 2020). "Shell to Cut Up to 9,000 Jobs". The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/shell-to-cut-up-to-9-000-jobs-11601457301?mod=business_lead_pos12.

- ↑ "Oil & Gas Stock Roundup: Exxon Ups Emission Goal, Shell's Q4 Update, Flurry of M&A". Yahoo Finance. 23 December 2020. https://finance.yahoo.com/news/oil-gas-stock-roundup-exxon-132201930.html.

- ↑ "Royal Dutch Shell sees huge loss as pandemic hits oil demand" (in en-GB). BBC News. 4 February 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-55931523.

- ↑ Good, Allen (8 February 2021). "Shell Increases Dividend Again With Q4 Results; Attention Turns to Upcoming Strategic Update". https://www.morningstar.com/stocks/xnys/rds.a/quote.

- ↑ Constable, Simon (11 February 2021). "Oil Prices Are Rebounding. Why Royal Dutch Shell Stock Is Looking Cheap." (in en-US). https://www.barrons.com/articles/oil-prices-are-rebounding-why-royal-dutch-shell-stock-looks-attractive-51613035800.

- ↑ "Shell plans to move headquarters to the UK". BBC. 15 November 2021. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-59288593.

- ↑ "Shell pulls out of Cambo oilfield project" (in en). 2 December 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/dec/02/shell-pulls-out-of-cambo-oilfield-project.

- ↑ Payne, Julia (4 March 2022). "Shell buys cargo of Russian crude loading mid-March from Trafigura" (in en). Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/shell-buys-cargo-russian-crude-loading-mid-march-trafigura-2022-03-04/.

- ↑ Bousso, Ron (5 March 2022). "Shell to put profits from Russian oil trade into Ukraine aid fund" (in en). Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/shell-put-profits-russian-oil-trade-into-ukraine-aid-fund-2022-03-05/.

- ↑ "Ukraine war latest: Shell to stop buying Russian oil and gas". Financial Times. 8 March 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/a29d2d7d-fb07-4976-bd76-45100df07bbf.

- ↑ "Shell makes record profits as Ukraine war shakes energy markets". Financial Times. 5 May 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/b2713bd1-afa5-4638-ab2d-be0c4e8a7ab7.

- ↑ "Oil giants reap record profits as war rages in Ukraine, energy prices soar: Here's how much they made". USA Today. 7 May 2022. https://eu.usatoday.com/story/money/economy/2022/05/07/oil-company-record-profits-2022/9686761002/.

- ↑ "Shell reports highest profits in 115 years". BBC News. 2 February 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-64489147.

- ↑ "Royal Dutch Shell: Directors & Officers". FT.com. https://markets.ft.com/data/equities/tearsheet/directors?s=RDSA:LSE.

- ↑ "Shell press release". http://www.shell.com/home/content/media/news_and_library/press_releases/2008/peter_voser_ceo_29102008.html.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 82.3 82.4 "Leading in the 21st century: An interview with Shell's Ann Pickard". June 2014. http://www.mckinsey.com/Insights/Leading_in_the_21st_century/Leading_in_the_21st_century_An_interview_with_Shells_Ann_Pickard?cid=other-eml-alt-mip-mck-oth-1406.

- ↑ Sweney, Mark (15 September 2022). "Shell appoints Wael Sawan to replace outgoing chief Ben van Beurden". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2022/sep/15/shell-appoints-wael-sawan-to-replace-outgoing-chief-ben-van-beurden.

- ↑ "About Shell – The history of the Shell logo". About Shell. Shell International B.V.. 15 June 2007. http://www.shell.com/home/content/aboutshell/who_we_are/our_history/history_of_pecten/.

- ↑ "Shell Haven celebrate a new jetty facility". Shell. http://www.shell.co.uk/media/2011-media-releases/shell-haven.html.

- ↑ Business Superbrands, Editor: Marcel Knobil, Author James Curtis (2000), Superbrands Ltd. ISBN 978-0-9528153-4-1, p. 93.

- ↑ "raymod loewy logos". designboom.com. http://www.designboom.com/portrait/loewy.html.

- ↑ "1980s to the new millennium". Shell Global. 17 December 2012. http://www.shell.com/global/aboutshell/who-we-are/our-history/1980s-to-new-century.html.

- ↑ Nasralla, Shadia; Ravikumar, Sachin (15 November 2021). "Shell ditches the Dutch, seeks move to London in overhaul". Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/uk/shell-proposes-single-share-structure-tax-residence-uk-2021-11-15/.

- ↑ "What we do". Shell. http://www.shell.com/about-us/what-we-do.html.

- ↑ "Vertical integration". The Economist. 30 March 2009. http://www.economist.com/node/13396061.

- ↑ "Industry Overview". Petroleum Services Association of Canada. http://www.psac.ca/business/industry-overview/.

- ↑ "Facelift for Shell logo in pounds 500m 'new look' drive: Petrol giant plans to update outlets in 100 countries ready for next century". The Independent. 30 August 1993. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/facelift-for-shell-logo-in-pounds-500m-new-look-drive-petrol-giant-plans-to-update-outlets-in-100-1464484.html.

- ↑ "Shell to become full-time DJR Team Penske backer". Motorsport.com. 3 October 2016. http://www.motorsport.com/v8supercars/news/shell-to-become-full-time-djr-team-penske-backer-834696/.

- ↑ "IndyCar to use fully renewable Shell fuel in 2023". The Chequered Flag. 28 May 2022. https://www.thecheckeredflag.co.uk/2022/05/indycar-to-use-fully-renewable-shell-fuel-in-2023/.

- ↑ "Shell initiates Beaufort Sea oil exploration". Offshore Magazine (Pennwell Corporation). 17 March 2006. http://www.offshore-mag.com/articles/2006/03/shell-initiates-beaufort-sea-oil-exploration.html.

- ↑ Bailey, Alan (4 February 2007). "Shell proposes 18 wells". Petroleum News 12 (5). http://www.petroleumnews.com/pntruncate/761266456.shtml.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 98.3 "What I learned aboard Shell's grounded Alaskan oil rig". 3 January 2013. http://fortune.com/2013/01/03/what-i-learned-aboard-shells-grounded-alaskan-oil-rig/.

- ↑ Eaton, Joe (27 July 2012). "Shell Scales Back 2012 Arctic Drilling Goals". National Geographic. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/energy/shell-2012-arctic-drilling-goals/.

- ↑ Demer, Lisa (27 June 2012). "Shell drill rigs depart Seattle for Arctic waters in Alaska". Anchorage Daily News. http://www.adn.com/2012/06/27/2521835/shell-drill-rigs-leave-seattle.html.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 101.2 "What Shell's Kulluk Oil Rig Accident Means for Arctic Drilling". Hearst Communication, Inc. 1 January 2013. http://www.popularmechanics.com/science/energy/coal-oil-gas/kulluk-oil-rig-accident-arctic-drilling-14928526.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 Phil Radford (24 May 2010). "[BPresident Obama: Where Does BP Begin and Obama End?"]. The Huffington Post. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/philip-radford/bpresident-obama---where_b_587756.html.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Mat Smith (27 February 2013). "Shell halts Arctic drill plans for 2013". CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2013/02/27/us/shell-alaska/index.html?hpt=us_c2.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 Terry Macalister (30 January 2014). "Shell shelves plan to drill in Alaskan Arctic this summer". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/jan/30/shell-shelves-alaskan-arctic-drilling-oil.

- ↑ Shell's Arctic oil rig departs Seattle as 'kayaktivists' warn of disaster The Guardian 15 June 2015

- ↑ Activists protest at Shell's Finnish icebreaker rental . YLE, 16 March 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ↑ Laurie Tuffrey. "Greenpeace activists shut down 74 UK Shell petrol stations". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2012/jul/16/greenpeace-activists-shell-petrol.

- ↑ Dan Joling (8 January 2013). "Salazar announces Arctic offshore drilling review; Coast Guard investigates Shell grounding". The Morning Call. The Associated Press. http://www.mcall.com/news/nationworld/sns-ap-us--shell-arctic-drill-ship-20130108,0,4095375.story.

- ↑ Phil Radford and Benjamin Jealous (17 June 2013). "How Shell is trying to send a chill through activist groups across the country". Grist.org. http://grist.org/article/how-shell-is-trying-to-send-a-chill-through-activist-groups-across-the-country/.

- ↑ "Greenpeace protest at Shell Belgian F1 Grand Prix event – video" (Video upload). The Guardian. 27 August 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/video/2013/aug/27/shell-belgian-f-1-grand-prix-greenpeace-protest.

- ↑ "Shell abandons Alaska Arctic drilling". The Guardian. 28 September 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/sep/28/shell-ceases-alaska-arctic-drilling-exploratory-well-oil-gas-disappoints.

- ↑ Beekman, Daniel (14 May 2015). "More protests planned after giant oil rig muscles in". The Seattle Times. http://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/protesters-launching-kayaks-to-unwelcome-oil-rig-to-seattle/.

- ↑ "'Paddle in Seattle' Arctic oil drilling protest". BBC. 17 May 2015. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-32770382.

- ↑ Vice (6 May 2015). "Shell Plans to Drill in the Arctic This Summer and It's Already Failed a Coast Guard Inspection". https://news.vice.com/article/shell-plans-to-drill-in-the-arctic-this-summer-and-its-already-failed-a-coast-guard-inspection.

- ↑ "Shell's Record Adds to the Anger of Those Opposing Arctic Drilling". The New York Times. 12 May 2015. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/13/us/shells-record-adds-to-the-anger-of-those-opposing-arctic-drilling.html.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 "Shell's Prelude FLNG Project: An Offshore Revolution?". Capitol Information Group, Inc. 3 June 2011. http://www.investingdaily.com/13544/shells-prelude-flng-project-an-offshore-revolution/.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 "Shell's massive Prelude hull world's biggest-ever floating vessel and first ocean-based LNG plant". Financial Post. 3 December 2013. http://business.financialpost.com/2013/12/03/record-breaking-lng-ship-launched-bigger-one-planned/?__federated=1.

- ↑ "Shell's Prelude FLNG to start production in 2017?". LNG World News. 14 April 2016. https://www.lngworldnews.com/shells-prelude-flng-to-start-production-in-2017/.