Confrontation analysis

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

Confrontation analysis (also known as dilemma analysis) is an operational analysis technique used to structure, understand, and analyze multi-party interactions, such as negotiations or conflicts. It serves as the mathematical foundation for drama theory.

While based on game theory, confrontation analysis differs in that it focuses on the idea that players may redefine the game during the interaction, often due to the influence of emotions. In traditional game theory, players generally work within a fixed set of rules (represented by a decision matrix). However, confrontation analysis sees the interaction as a sequence of linked decisions, where the rules or perceptions of the game can shift over time, influenced by emotional dilemmas or psychological factors that arise during the interaction.[1]

Derivation and use

Confrontation analysis was devised by Professor Nigel Howard in the early 1990s drawing from his work on game theory and metagame analysis. It has been turned to defence,[2] political, legal, financial[3] and commercial applications.[4]

Much of the theoretical background to General Rupert Smith's book The Utility of Force drew its inspiration from the theory of confrontation analysis.

I am in debt to Professor Nigel Howard, whose explanation of Confrontation Analysis and Game Theory at a seminar in 1998 excited my interest. Our subsequent discussions helped me to order my thoughts and the lessons I had learned into a coherent structure with the result that, for the first time, I was able to understand my experiences within a theoretical model which allowed me to use them further

– General Rupert Smith, The Utility of Force (p.xvi)

Confrontation analysis can also be used in a decision workshop as structure to support role-playing[3] for training, analysis and decision rehearsal.

Confrontation analysis was continually developed by Professor Nigel Howard during his lifetime and was considerably revised and simplified (from Version 1 to Version 2) a year or so before his death. This means that much of what he wrote was about Version 1, although much of the follow-on work since then has embraced Version 2.

Method (Version 2)

Confrontation analysis looks on an interaction as a sequence of confrontations. During each confrontation the parties communicate until they have made their positions[6] clear to one another. These positions can be expressed as a card table (also known as an options board[5]) of yes/no decisions. For each decision each party communicates what they would like to happen (their position[6]) and what will happen if they cannot agree (the threatened future). These interactions produce dilemmas[1] and the card table changes as players attempt to eliminate these.

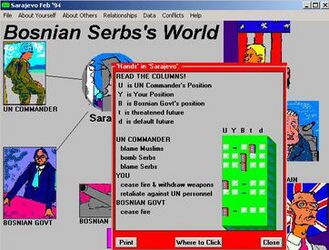

Consider the example on the right (Initial Card Table), taken from the 1995 Bosnian Conflict.[7] This represents an interaction between the Bosnian Serbs and the United Nations forces over the safe areas. The Bosnian Serbs had Bosniak enclaves surrounded and were threatening to attack.

Each side had a position as to what they wanted to happen:

The Bosnian Serbs wanted (see 4th column):

- To be able to attack the enclaves

- NOT to withdraw their heavy weapons from the enclaves

- For the UN NOT to use air strikes

The UN wanted (See 5th column):

- The Bosnian Serbs NOT to attack the enclaves

- The Bosnian Serbs to withdraw their heavy weapons

- The Bosnian Serbs NOT to take hostages.

If no further changes were made then what the sides were saying would happen was (see 1st column):

- The Bosnian Serbs said they would attack the enclaves

- The Bosnian Serbs said they would NOT withdraw their heavy weapons

- The Bosnian Serbs said they would take hostages if the UN uses air strikes

- The UN said it would initiate air strikes. However the Bosnian Serbs DID NOT BELIEVE them. (Hence the question mark on the Card Table).

Confrontation analysis then specifies a number of precisely defined dilemmas[1] that occur to the parties following from the structure of the card tables. It states that motivated by the desire to eliminate these dilemmas, the parties involved will CHANGE THE CARD TABLE, to eliminate their problem.

In the situation at the start the Bosnian Serbs have no dilemmas, but the UN has four. It has three persuasion dilemmas[8] in that the Bosnian Serbs are not going to do the three things they want them to (not attack the enclaves, withdraw the heavy weapons and not take hostages). It also has a rejection dilemma[9] in that the Bosnian Serbs do not believe they will actually use the air strikes, as they think the UN will submit to their position, for fear of having hostages taken.

Faced with these dilemmas, the UN modified the card table to eliminate its dilemmas. It took two actions:

Firstly, it withdrew its forces from the positions where they were vulnerable to being taken hostage. This action eliminated the Bosnian Serbs' option (card) of taking hostages.

Secondly, with the addition of the Rapid Reaction Force, and in particular its artillery the UN had an additional capability to engage Bosnian Serb weapons; they added the card "Use artillery against Bosnian Serbs". Because of this, the UN's threat of air strikes became more credible. The situation changed to that of the Second Card Table:

The Bosnian Serbs wanted (see 4th column):

- To be able to attack the enclaves

- NOT to withdraw heavy weapons from the enclaves

- For the UN NOT to use air strikes

- For the UN NOT to use artillery

The UN wanted (See 5th column):

- The Bosnian Serbs NOT to attack the enclaves

- The Bosnian Serbs to withdraw their heavy weapons

If no further changes were made then what the sides were saying would happen was (see 1st column):

- The Bosnian Serbs said they would attack the enclaves, but the UN did not believe them.

- The Bosnian Serbs said they would NOT withdraw their heavy weapons, but the UN did not believe them.

- The UN said it would use artillery. The Bosnian Serbs believed this.

- The UN said it would use air strikes. This time, however, the Bosnian Serbs believed them.

Faced with this new situation, the Bosnian Serbs modified their position to accept the UN proposal. The final table was an agreement as shown in the Final Card table (see thumbnail and picture).

Confrontation analysis does not necessarily produce a win-win solution (although end states are more likely to remain stable if they do); however, the word confrontation should not necessarily imply that any negotiations should be carried out in an aggressive way.

The card tables are isomorphic to game theory models, but are not built with the aim of finding a solution. Instead, the aim is to find the dilemmas facing characters and so help to predict how they will change the table itself. Such prediction requires not only analysis of the model and its dilemmas, but also exploration of the reality outside the model; without this it is impossible to decide which ways of changing the model in order to eliminate dilemmas might be rationalized by the characters.

Sometimes analysis of the ticks and crosses can be supported by values showing the payoff to each of the parties.[10]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 See definition of Dilemma

- ↑ See The future of Libya

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "role playing... can also be used by investors in the form of "confrontation analysis' such as that organised by former military analyst Mike Young's [1]" – Greek Dungeons and German Dragons, James Macintosh, Financial Times, 9 November 2011.

- ↑ See Letting agency case study

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 See definition of Options Board/Card table

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 See definition of Position

- ↑ This example developed from that described in Smith R, Tait A, Howard N (1999) Confrontations in War and Peace. Proceedings of the 6th international Command and Control Research and Technology Symposium, U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland, 19–20 June 2001

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 See definition of Persuasion Dilemma

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 See definition of Rejection Dilemma

- ↑ See understanding the tables used in confrontation analysis

External links

- Decision Workshops - A public domain website about how to do confrontation analysis with many examples

- Dilemma Explorer - A software application to do Version 2 of Confrontation Analysis

- Confrontation Manager — A software application using Version 1 of Confrontation Analysis.

- Confronteer an iPhone app to do Version 2 of Confrontation Analysis.

- N. Howard, 'Confrontation Analysis: How to win operations other than war', CCRP Publications, 1999 (used Version 1 of Confrontation Analysis)

- P. Bennett, J. Bryant and N. Howard, 'Drama Theory and Confrontation Analysis' — can be found (along with other recent PSM methods) in: J. V. Rosenhead and J. Mingers (eds) Rational Analysis for a Problematic World Revisited: problem structuring methods for complexity, uncertainty and conflict, Wiley, 2001. (Version 1)

- J. Bryant, The Six Dilemmas of Collaboration: inter-organisational relationships as drama, Wiley, 2003. (Version 1)

- N. Howard, Paradoxes of Rationality', MIT Press, 1971 (Version 1)

- How to structure disputes using Confrontation Analysis contains an illustrated explanation of Version 2 of Confrontation Analysis.

- Speed Confrontation Management a brief "How to" manual on doing Confrontation Analysis without using an Options Table.

|

KSF

KSF