Connected space

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

In topology and related branches of mathematics, a connected space is a topological space that cannot be represented as the union of two or more disjoint non-empty open subsets. Connectedness is one of the principal topological properties that are used to distinguish topological spaces.

A subset of a topological space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is a connected set if it is a connected space when viewed as a subspace of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math].

Some related but stronger conditions are path connected, simply connected, and [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-connected. Another related notion is locally connected, which neither implies nor follows from connectedness.

Formal definition

A topological space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is said to be disconnected if it is the union of two disjoint non-empty open sets. Otherwise, [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is said to be connected. A subset of a topological space is said to be connected if it is connected under its subspace topology. Some authors exclude the empty set (with its unique topology) as a connected space, but this article does not follow that practice.

For a topological space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] the following conditions are equivalent:

- [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is connected, that is, it cannot be divided into two disjoint non-empty open sets.

- The only subsets of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] which are both open and closed (clopen sets) are [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] and the empty set.

- The only subsets of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] with empty boundary are [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] and the empty set.

- [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] cannot be written as the union of two non-empty separated sets (sets for which each is disjoint from the other's closure).

- All continuous functions from [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ \{ 0, 1 \} }[/math] are constant, where [math]\displaystyle{ \{ 0, 1 \} }[/math] is the two-point space endowed with the discrete topology.

Historically this modern formulation of the notion of connectedness (in terms of no partition of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] into two separated sets) first appeared (independently) with N.J. Lennes, Frigyes Riesz, and Felix Hausdorff at the beginning of the 20th century. See [1] for details.

Connected components

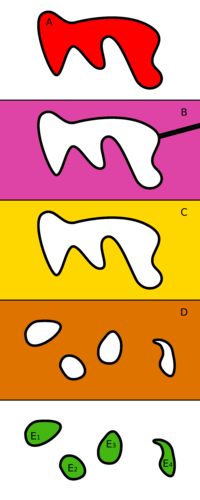

Given some point [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] in a topological space [math]\displaystyle{ X, }[/math] the union of any collection of connected subsets such that each contained [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] will once again be a connected subset. The connected component of a point [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is the union of all connected subsets of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] that contain [math]\displaystyle{ x; }[/math] it is the unique largest (with respect to [math]\displaystyle{ \subseteq }[/math]) connected subset of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] that contains [math]\displaystyle{ x. }[/math] The maximal connected subsets (ordered by inclusion [math]\displaystyle{ \subseteq }[/math]) of a non-empty topological space are called the connected components of the space. The components of any topological space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] form a partition of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]: they are disjoint, non-empty and their union is the whole space. Every component is a closed subset of the original space. It follows that, in the case where their number is finite, each component is also an open subset. However, if their number is infinite, this might not be the case; for instance, the connected components of the set of the rational numbers are the one-point sets (singletons), which are not open. Proof: Any two distinct rational numbers [math]\displaystyle{ q_1\lt q_2 }[/math] are in different components. Take an irrational number [math]\displaystyle{ q_1 \lt r \lt q_2, }[/math] and then set [math]\displaystyle{ A = \{q \in \Q : q \lt r\} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B = \{q \in \Q : q \gt r\}. }[/math] Then [math]\displaystyle{ (A,B) }[/math] is a separation of [math]\displaystyle{ \Q, }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ q_1 \in A, q_2 \in B }[/math]. Thus each component is a one-point set.

Let [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma_x }[/math] be the connected component of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] in a topological space [math]\displaystyle{ X, }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma_x' }[/math] be the intersection of all clopen sets containing [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] (called quasi-component of [math]\displaystyle{ x. }[/math]) Then [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma_x \subset \Gamma'_x }[/math] where the equality holds if [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is compact Hausdorff or locally connected. [2]

Disconnected spaces

A space in which all components are one-point sets is called totally disconnected. Related to this property, a space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is called totally separated if, for any two distinct elements [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math], there exist disjoint open sets [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] containing [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math] containing [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is the union of [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math]. Clearly, any totally separated space is totally disconnected, but the converse does not hold. For example take two copies of the rational numbers [math]\displaystyle{ \Q }[/math], and identify them at every point except zero. The resulting space, with the quotient topology, is totally disconnected. However, by considering the two copies of zero, one sees that the space is not totally separated. In fact, it is not even Hausdorff, and the condition of being totally separated is strictly stronger than the condition of being Hausdorff.

Examples

- The closed interval [math]\displaystyle{ [0, 2) }[/math] in the standard subspace topology is connected; although it can, for example, be written as the union of [math]\displaystyle{ [0, 1) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ [1, 2), }[/math] the second set is not open in the chosen topology of [math]\displaystyle{ [0, 2). }[/math]

- The union of [math]\displaystyle{ [0, 1) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ (1, 2] }[/math] is disconnected; both of these intervals are open in the standard topological space [math]\displaystyle{ [0, 1) \cup (1, 2]. }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ (0, 1) \cup \{ 3 \} }[/math] is disconnected.

- A convex subset of [math]\displaystyle{ \R^n }[/math] is connected; it is actually simply connected.

- A Euclidean plane excluding the origin, [math]\displaystyle{ (0, 0), }[/math] is connected, but is not simply connected. The three-dimensional Euclidean space without the origin is connected, and even simply connected. In contrast, the one-dimensional Euclidean space without the origin is not connected.

- A Euclidean plane with a straight line removed is not connected since it consists of two half-planes.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \R }[/math], the space of real numbers with the usual topology, is connected.

- The Sorgenfrey line is disconnected.[3]

- If even a single point is removed from [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R} }[/math], the remainder is disconnected. However, if even a countable infinity of points are removed from [math]\displaystyle{ \R^n }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ n \geq 2, }[/math] the remainder is connected. If [math]\displaystyle{ n\geq 3 }[/math], then [math]\displaystyle{ \R^n }[/math] remains simply connected after removal of countably many points.

- Any topological vector space, e.g. any Hilbert space or Banach space, over a connected field (such as [math]\displaystyle{ \R }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \Complex }[/math]), is simply connected.

- Every discrete topological space with at least two elements is disconnected, in fact such a space is totally disconnected. The simplest example is the discrete two-point space.[4]

- On the other hand, a finite set might be connected. For example, the spectrum of a discrete valuation ring consists of two points and is connected. It is an example of a Sierpiński space.

- The Cantor set is totally disconnected; since the set contains uncountably many points, it has uncountably many components.

- If a space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is homotopy equivalent to a connected space, then [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is itself connected.

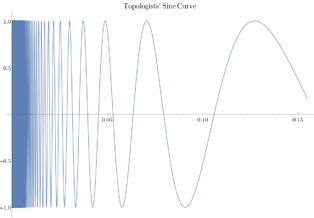

- The topologist's sine curve is an example of a set that is connected but is neither path connected nor locally connected.

- The general linear group [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{GL}(n, \R) }[/math] (that is, the group of [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-by-[math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] real, invertible matrices) consists of two connected components: the one with matrices of positive determinant and the other of negative determinant. In particular, it is not connected. In contrast, [math]\displaystyle{ \operatorname{GL}(n, \Complex) }[/math] is connected. More generally, the set of invertible bounded operators on a complex Hilbert space is connected.

- The spectra of commutative local ring and integral domains are connected. More generally, the following are equivalent[5]

- The spectrum of a commutative ring [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] is connected

- Every finitely generated projective module over [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] has constant rank.

- [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] has no idempotent [math]\displaystyle{ \ne 0, 1 }[/math] (i.e., [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] is not a product of two rings in a nontrivial way).

An example of a space that is not connected is a plane with an infinite line deleted from it. Other examples of disconnected spaces (that is, spaces which are not connected) include the plane with an annulus removed, as well as the union of two disjoint closed disks, where all examples of this paragraph bear the subspace topology induced by two-dimensional Euclidean space.

Path connectedness

A path-connected space is a stronger notion of connectedness, requiring the structure of a path. A path from a point [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] to a point [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] in a topological space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is a continuous function [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] from the unit interval [math]\displaystyle{ [0,1] }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ f(0)=x }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ f(1)=y }[/math]. A path-component of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is an equivalence class of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] under the equivalence relation which makes [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] equivalent to [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] if there is a path from [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math]. The space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is said to be path-connected (or pathwise connected or [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{0} }[/math]-connected) if there is exactly one path-component, i.e. if there is a path joining any two points in [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]. Again, many authors exclude the empty space (by this definition, however, the empty space is not path-connected because it has zero path-components; there is a unique equivalence relation on the empty set which has zero equivalence classes).

Every path-connected space is connected. The converse is not always true: examples of connected spaces that are not path-connected include the extended long line [math]\displaystyle{ L^* }[/math] and the topologist's sine curve.

Subsets of the real line [math]\displaystyle{ \R }[/math] are connected if and only if they are path-connected; these subsets are the intervals and rays of [math]\displaystyle{ \R }[/math]. Also, open subsets of [math]\displaystyle{ \R^n }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \C^n }[/math] are connected if and only if they are path-connected. Additionally, connectedness and path-connectedness are the same for finite topological spaces.

Arc connectedness

A space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is said to be arc-connected or arcwise connected if any two topologically distinguishable points can be joined by an arc, which is an embedding [math]\displaystyle{ f : [0, 1] \to X }[/math]. An arc-component of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is a maximal arc-connected subset of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math]; or equivalently an equivalence class of the equivalence relation of whether two points can be joined by an arc or by a path whose points are topologically indistinguishable.

Every Hausdorff space that is path-connected is also arc-connected; more generally this is true for a [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math]-Hausdorff space, which is a space where each image of a path is closed. An example of a space which is path-connected but not arc-connected is given by the line with two origins; its two copies of [math]\displaystyle{ 0 }[/math] can be connected by a path but not by an arc.

Intuition for path-connected spaces does not readily transfer to arc-connected spaces. Let [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] be the line with two origins. The following are facts whose analogues hold for path-connected spaces, but do not hold for arc-connected spaces:

- Continuous image of arc-connected space may not be arc-connected: for example, a quotient map from an arc-connected space to its quotient with countably many (at least 2) topologically distinguishable points cannot be arc-connected due to too small cardinality.

- Arc-components may not be disjoint. For example, [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] has two overlapping arc-components.

- Arc-connected product space may not be a product of arc-connected spaces. For example, [math]\displaystyle{ X \times \mathbb{R} }[/math] is arc-connected, but [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is not.

- Arc-components of a product space may not be products of arc-components of the marginal spaces. For example, [math]\displaystyle{ X \times \mathbb{R} }[/math] has a single arc-component, but [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] has two arc-components.

- If arc-connected subsets have a non-empty intersection, then their union may not be arc-connected. For example, the arc-components of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] intersect, but their union is not arc-connected.

Local connectedness

A topological space is said to be locally connected at a point [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] if every neighbourhood of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] contains a connected open neighbourhood. It is locally connected if it has a base of connected sets. It can be shown that a space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is locally connected if and only if every component of every open set of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is open.

Similarly, a topological space is said to be locally path-connected if it has a base of path-connected sets. An open subset of a locally path-connected space is connected if and only if it is path-connected. This generalizes the earlier statement about [math]\displaystyle{ \R^n }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \C^n }[/math], each of which is locally path-connected. More generally, any topological manifold is locally path-connected.

Locally connected does not imply connected, nor does locally path-connected imply path connected. A simple example of a locally connected (and locally path-connected) space that is not connected (or path-connected) is the union of two separated intervals in [math]\displaystyle{ \R }[/math], such as [math]\displaystyle{ (0,1) \cup (2,3) }[/math].

A classical example of a connected space that is not locally connected is the so called topologist's sine curve, defined as [math]\displaystyle{ T = \{(0,0)\} \cup \left\{ \left(x, \sin\left(\tfrac{1}{x}\right)\right) : x \in (0, 1] \right\} }[/math], with the Euclidean topology induced by inclusion in [math]\displaystyle{ \R^2 }[/math].

Set operations

The intersection of connected sets is not necessarily connected.

The union of connected sets is not necessarily connected, as can be seen by considering [math]\displaystyle{ X=(0,1) \cup (1,2) }[/math].

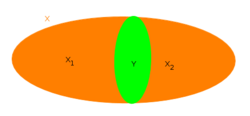

Each ellipse is a connected set, but the union is not connected, since it can be partitioned to two disjoint open sets [math]\displaystyle{ U }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math].

This means that, if the union [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is disconnected, then the collection [math]\displaystyle{ \{X_i\} }[/math] can be partitioned to two sub-collections, such that the unions of the sub-collections are disjoint and open in [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] (see picture). This implies that in several cases, a union of connected sets is necessarily connected. In particular:

- If the common intersection of all sets is not empty ([math]\displaystyle{ \bigcap X_i \neq \emptyset }[/math]), then obviously they cannot be partitioned to collections with disjoint unions. Hence the union of connected sets with non-empty intersection is connected.

- If the intersection of each pair of sets is not empty ([math]\displaystyle{ \forall i,j: X_i \cap X_j \neq \emptyset }[/math]) then again they cannot be partitioned to collections with disjoint unions, so their union must be connected.

- If the sets can be ordered as a "linked chain", i.e. indexed by integer indices and [math]\displaystyle{ \forall i: X_i \cap X_{i+1} \neq \emptyset }[/math], then again their union must be connected.

- If the sets are pairwise-disjoint and the quotient space [math]\displaystyle{ X / \{X_i\} }[/math] is connected, then X must be connected. Otherwise, if [math]\displaystyle{ U \cup V }[/math] is a separation of X then [math]\displaystyle{ q(U) \cup q(V) }[/math] is a separation of the quotient space (since [math]\displaystyle{ q(U), q(V) }[/math] are disjoint and open in the quotient space).[6]

The set difference of connected sets is not necessarily connected. However, if [math]\displaystyle{ X \supseteq Y }[/math] and their difference [math]\displaystyle{ X \setminus Y }[/math] is disconnected (and thus can be written as a union of two open sets [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ X_2 }[/math]), then the union of [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] with each such component is connected (i.e. [math]\displaystyle{ Y \cup X_{i} }[/math] is connected for all [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]).

By contradiction, suppose [math]\displaystyle{ Y \cup X_{1} }[/math] is not connected. So it can be written as the union of two disjoint open sets, e.g. [math]\displaystyle{ Y \cup X_{1}=Z_{1} \cup Z_{2} }[/math]. Because [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] is connected, it must be entirely contained in one of these components, say [math]\displaystyle{ Z_1 }[/math], and thus [math]\displaystyle{ Z_2 }[/math] is contained in [math]\displaystyle{ X_1 }[/math]. Now we know that: [math]\displaystyle{ X=\left(Y \cup X_{1}\right) \cup X_{2}=\left(Z_{1} \cup Z_{2}\right) \cup X_{2}=\left(Z_{1} \cup X_{2}\right) \cup\left(Z_{2} \cap X_{1}\right) }[/math] The two sets in the last union are disjoint and open in [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math], so there is a separation of [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math], contradicting the fact that [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is connected.

Theorems

- Main theorem of connectedness: Let [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ Y }[/math] be topological spaces and let [math]\displaystyle{ f:X\rightarrow Y }[/math] be a continuous function. If [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] is (path-)connected then the image [math]\displaystyle{ f(X) }[/math] is (path-)connected. This result can be considered a generalization of the intermediate value theorem.

- Every path-connected space is connected.

- In a locally path-connected space, every open connected set is path-connected.

- Every locally path-connected space is locally connected.

- A locally path-connected space is path-connected if and only if it is connected.

- The closure of a connected subset is connected. Furthermore, any subset between a connected subset and its closure is connected.

- The connected components are always closed (but in general not open)

- The connected components of a locally connected space are also open.

- The connected components of a space are disjoint unions of the path-connected components (which in general are neither open nor closed).

- Every quotient of a connected (resp. locally connected, path-connected, locally path-connected) space is connected (resp. locally connected, path-connected, locally path-connected).

- Every product of a family of connected (resp. path-connected) spaces is connected (resp. path-connected).

- Every open subset of a locally connected (resp. locally path-connected) space is locally connected (resp. locally path-connected).

- Every manifold is locally path-connected.

- Arc-wise connected space is path connected, but path-wise connected space may not be arc-wise connected

- Continuous image of arc-wise connected set is arc-wise connected.

Graphs

Graphs have path connected subsets, namely those subsets for which every pair of points has a path of edges joining them. But it is not always possible to find a topology on the set of points which induces the same connected sets. The 5-cycle graph (and any [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]-cycle with [math]\displaystyle{ n\gt 3 }[/math] odd) is one such example.

As a consequence, a notion of connectedness can be formulated independently of the topology on a space. To wit, there is a category of connective spaces consisting of sets with collections of connected subsets satisfying connectivity axioms; their morphisms are those functions which map connected sets to connected sets (Muscat Buhagiar). Topological spaces and graphs are special cases of connective spaces; indeed, the finite connective spaces are precisely the finite graphs.

However, every graph can be canonically made into a topological space, by treating vertices as points and edges as copies of the unit interval (see topological graph theory#Graphs as topological spaces). Then one can show that the graph is connected (in the graph theoretical sense) if and only if it is connected as a topological space.

Stronger forms of connectedness

There are stronger forms of connectedness for topological spaces, for instance:

- If there exist no two disjoint non-empty open sets in a topological space [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ X }[/math] must be connected, and thus hyperconnected spaces are also connected.

- Since a simply connected space is, by definition, also required to be path connected, any simply connected space is also connected. If the "path connectedness" requirement is dropped from the definition of simple connectivity, a simply connected space does not need to be connected.

- Yet stronger versions of connectivity include the notion of a contractible space. Every contractible space is path connected and thus also connected.

In general, any path connected space must be connected but there exist connected spaces that are not path connected. The deleted comb space furnishes such an example, as does the above-mentioned topologist's sine curve.

See also

- Connected component (graph theory)

- Connectedness locus

- Domain (mathematical analysis) – Connected open subset of a topological space

- Extremally disconnected space – Topological space in which the closure of every open set is open

- Locally connected space – Property of topological spaces

- Uniformly connected space – Type of uniform space

- Pixel connectivity

References

- ↑ Wilder, R.L. (1978). "Evolution of the Topological Concept of "Connected"". American Mathematical Monthly 85 (9): 720–726. doi:10.2307/2321676.

- ↑ "General topology - Components of the set of rational numbers". https://math.stackexchange.com/q/1314013.

- ↑ Stephen Willard (1970). General Topology. Dover. p. 191. ISBN 0-486-43479-6.

- ↑ George F. Simmons (1968). Introduction to Topology and Modern Analysis. McGraw Hill Book Company. p. 144. ISBN 0-89874-551-9.

- ↑ Charles Weibel, The K-book: An introduction to algebraic K-theory

- ↑ Brandsma, Henno (February 13, 2013). "How to prove this result involving the quotient maps and connectedness?". Stack Exchange. https://math.stackexchange.com/q/302118.

- ↑ Marek (February 13, 2013). "How to prove this result about connectedness?". Stack Exchange. https://math.stackexchange.com/q/302094.

Further reading

- Munkres, James R. (2000). Topology, Second Edition. Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-181629-2.

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Connected Set". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/ConnectedSet.html.

- Hazewinkel, Michiel, ed. (2001), "Connected space", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer Science+Business Media B.V. / Kluwer Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-1-55608-010-4, https://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Main_Page

- Muscat, J; Buhagiar, D (2006). "Connective Spaces". Mem. Fac. Sci. Eng. Shimane Univ., Series B: Math. Sc. 39: 1–13. http://www.math.shimane-u.ac.jp/memoir/39/D.Buhagiar.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-17..

|

KSF

KSF