Coral reefs of the Solomon Islands

Topic: Earth

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 18 min

Aerial view of Solomon Islands | |

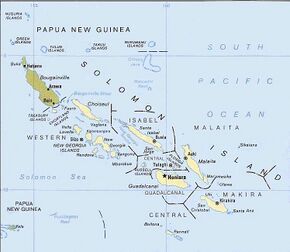

The Solomon Islands archipelago | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] 9°28′S 159°49′E / 9.467°S 159.817°E |

| Archipelago | Solomon Islands archipelago |

| Total islands | 6 main islands and more than 986 smaller islands |

| Major islands | Choiseul, the New Georgia Islands, Santa Isabel, Malaita, Makira (San Cristobal), Guadalcanal. |

| Administration | |

Solomon Islands | |

The Coral reefs of the Solomon Islands consists of six major islands and over 986 smaller islands,[1] in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and northwest of Vanuatu. The Solomon Islands lie between latitudes 5° and 13°S, and longitudes 155° and 169°E. The distance between the westernmost and easternmost islands is about 1,500 km (930 mi). The Santa Cruz Islands are situated north of Vanuatu and are especially isolated at more than 200 km (120 mi) from the other islands. The Solomon Islands (the Solomons) has the 22nd largest Exclusive Economic Zone of 1,589,477 km2 (613,701 sq mi) of the Pacific Ocean.

The Solomons has a rich and diverse marine life, including coral reefs and seagrass meadows. The islands are part of the Coral Triangle, the region of the western Pacific with the World's greatest diversity of corals and coral reef species. The recognizable reef systems in the Solomons are: fringing reef, patch reef, barrier reef, atoll reefs and lagoon environment.[1] The baseline survey of marine biodiversity in 2004,[2][3] identified the Solomons as having the second highest diversity of corals in the World, second only to the Raja Ampat Islands in eastern Indonesia.[4]

The Coral reefs of the Solomons make up nearly 6,750 km2 (2,610 sq mi) of total coral reef area.[5] There are 113 Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMA) containing an estimated 155 no-take zones in the Solomons. The largest LMMA, with a contiguous 13 km (10 mi) no-take zone, is on Tetepare Island.[6]

More than 90% of inshore coastal areas, reefs and islets in the Solomons are owned and managed under the customary marine tenure system, under which family units, clans, or tribes have rights to access and use marine resources. This kinship group ownership system is recognised under the Solomon Islands Constitution.[7] The methods of management of marine resources under the customary marine tenure system include limited entry, closed seasons, closed areas, size limits, species prohibitions and restrictions on the use of fishing equipment.[7] The success or failure of conservation efforts on coral reefs largely depends on the attitudes of the communities owning them.[8]

Areas of high biodiversity and conservation value

A total 12 offshore sites and 53 inshore sites have been identified as Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) - areas of high biodiversity and conservation.[9] The highest-scoring sites were Marovo Lagoon and the Arnavon Community Marine Conservation Area.[9] The offshore sites are Roncador Reef, Ontong Java Atoll, Tikopia, and Vanikoro, an island in the Santa Cruz group.[9]

KBAs include:

- Reef sites and lagoons within Western Province, including Kennedy Island (Kasolo Island), Tetepare Island, Marovo Lagoon (which covers 450 km2 (170 sq mi),[10] the Zaira Resource Management Area on the western coast of Vangunu Island and New Georgia Island, and Mushroom Island at the edge of Roviana Lagoon, on the southern side of New Georgia.[9]

- Reef sites and lagoons within Choiseul Province including Zinoa Island that is located on the south-west side of Choiseul Island and includes the Zinoa Marine Conservation Area, which covers 150 ha or 1.5 km2 (0.58 sq mi) and consists of two small islands and associated reefs; Rabakel is a marine protected area (MPA), measuring 0.22 km2 (0.085 sq mi), at the northern end of Choiseul Island that includes a stretch of fringing coral reef; Moli Island, off the western side of Choiseul Island, which has a locally managed marine area (LMMA) that includes a stretch of fringing coral reef; and Muzo Island that is located towards the southern end of Choiseul Island that is fringed by a coral reef and is sheltered from strong wave action by a barrier reef directly to the south.[9]

- Reef sites and lagoons within Isabel Province including: the Arnavon Community Marine Conservation Area.[9]

- Reef sites and lagoons within Malaita Province including Langa Langa Lagoon or Akwalaafu; Lau Lagoon, the coral reef lagoon off the coast of Fanalei and Walande villages on the eastern side of Malaita Island; and Ndai or Dai, which is a small (3 by 7 kilometres (1.9 mi × 4.3 mi) elevated coral reef island 43 km (30 mi) off the northern end of Malaita Island.[9]

- Reef sites in Rennell and Bellona Province including Rennell Island,[9] and the Indispensable Reefs, which are a chain of three large coral atolls in the Coral Sea spread over a length of 114 km (70 mi), approximately 1,500 km (930 mi) south of Rennell Island. The atolls enclose deep lagoons. North Reef has two narrow openings in the north and northwest, with no islets. The reef has a total area of 100 km2 (39 sq mi), including the lagoon and reef flat. Middle Reef has a total area of 300 km2 (120 sq mi). A small islet is located near the center of the reef. South Reef has a total area of 100 km2 (39 sq mi).[9]

Structure of the reefs of the Solomon Islands

The Solomon Islands are located at the edge of the Solomon Sea Plate, the Pacific Plate and other oceanic tectonic plates. These autochthonous geological systems have tilted to push up and create some of islands, and some of islands are volcanic in origin.[11][12]

The coral reefs are developed by the carbonate-based skeletons of a variety of animals and algae. Slowly, over time, the reefs have built up to the surface in oceans.[13] Coral reefs are found in shallow, warm salt water. The sunlight filters through clear water and allows microscopic organisms to live and reproduce. Coral reefs are composed of tiny, fragile animals known as coral polyps. Coral reefs are significantly important because of the biodiversity, and are at risk from the detrimental effects of human action and inaction, such as overfishing; and heightened levels of nutrients in the water due to pollution from human waste, which feeds the growth of Macroalgae species (seaweed).

The coral reefs of the Solomons are predominantly fringing reefs, although Ontong Java Atoll and Sikaiana, are examples of coral atolls. Long submerged barrier reefs are uncommon in Solomons,[14] although there are some examples, including in the Reef Islands, a line of four reefs stretches westwards for 21 km (10 mi) while the Great Reef, which is further north, is about 25 km (20 mi) long.[8]

The fringing reefs of the Solomons are found off the mountainous volcanic islands of the Solomon Islands archipelago, which includes Choiseul, the Shortland Islands, the New Georgia Islands, Santa Isabel, the Russell Islands, the Florida Islands, Tulagi, Malaita, Maramasike, Ulawa, Owaraha (Santa Ana), Makira (San Cristobal), and the main island of Guadalcanal. Bougainville Island is the largest island in the archipelago, while it is geographically part of the Solomon Islands archipelago, it is politically an autonomous region of Papua New Guinea. The volcanic islands with fringing reefs include the remote, tiny outliers, Tikopia, Anuta, and Fatutaka.[8]

The largest coral reef systems in the Solomons are located where large lagoons are protected by raised or semi-submerged barrier reefs or by raised limestone islands, such as, Marovo Lagoon and Roviana Lagoon (on the southern side of New Georgia Island.[8] There are some large lagoon complexes are that are protected by volcanic islands, raised islands, sand cays, or barrier reefs. Examples of such as reefs are (1) Marau Sound in the eastern part of Guadalcanal; (2) Lau Lagoon on the northeast coast of Malaita; (3) in the vicinity of Vangunu in southeastern New Georgia; (4) in Gizo, on Vonavona island, and the lagoon of New Georgia; (5) along the northeastern coast of Choiseul; (6) on both sides of Manning Strait between Choiseul and Santa Isabel Island; (7) and adjacent to the Shortland Islands near Bougainville.[14]

Sikaiana (formerly called the Stewart Islands) is a small atoll 212 kilometres (132 miles) northeast of Malaita is almost 14 kilometres (8.7 miles) in length and its lagoon, known as Te Moana, is totally enclosed by the coral reef. Sikaiana is an example of a coral atoll formed from an oceanic volcano, with a coral reef growing around the shore of the volcano and then, over several million years, the volcano becomes extinct, eroded and subsided completely beneath the surface of the ocean. The reef and the small coral islets on top of it are all that is left of the original island, and a lagoon has taken the place of the former volcano. For the atoll to persist, the coral reef must be maintained at the sea surface, with coral growth matching any relative change in sea level (subsidence of the island or rising oceans).[15] On the atolls, an annular reef rim surrounds the lagoon, and may include natural reef channels.[16]

Rennell has a land area of 660 square kilometres (250 sq mi) that is about 80 kilometres (50 mi) long and 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) wide. It is the second largest raised coral atoll in the world.[17] Rennell Island is an example of a reef island also formed from an oceanic volcano that has a completely closed rim of dry land, with the remnants of a lagoon that has no direct connection to the open sea.

The Marovo lagoon is the second largest saltwater lagoon in the World at 700 km2 (270 sq mi). Huvadhu Atoll in the Maldives is the largest saltwater lagoon at 3,152 km2 (1,217 sq mi). Marovo lagoon is surrounded by Vangunu Island and Nggatokae Island, both extinct volcanic islands, at [ ⚑ ] 8°29′S 158°04′E / 8.48°S 158.07°E. It is part of the New Georgia Islands, which are located to the northwest of Guadalcanal and is protected by a double barrier reef system.

The volcanic island of Malaita includes, on the northwest coast, the Langa Langa Lagoon and the Lau Lagoon on the northeast coast. The Langa Langa Lagoon or Akwalaafu, is 18 by 21 kilometres (11 mi × 13 mi). The Lau Lagoon is more than 35 km (20 mi) long and contains about 60 artificial islands built on the reef.[18][19][20] The people of the Lau Lagoon continue to live on the reef islands.[21][19][20]

State of the reefs of the Solomon Islands

Surveys of marine biodiversity

The baseline survey of marine biodiversity in 2004,[22] identified 494 coral species, including nine potentially new species and extended the known range of 122 coral species to include the Solomons.[23] The 2004 survey also recorded 1,019 species of reef fish, of which 47 were species range extensions.[24]

There are 3 species of pearl oysters: Black-lip oyster (Pinctada margaritifera), White-lip oyster (Pinctada maxima), and Pteria penguin.[25][14]

Six species of giant clam (Tridacna) occur: Tridacna crocea; Hippopus hippopus; Tridacna squamosa; Tridacna maxima; Tridacna derasa (southern giant clam or Smooth giant clam); and Tridacna gigas, which can grow to 1 metre (3.281 ft).[10] These giant clams have been overharvested and restrictions now protect the resource for local subsistence use only. Only farmed shells are allowed to be marketed commercially.[8][25]

Erect coralline algae (red algae), and Halimeda (green macroalgae) was commonly found throughout the Solomons, particularly at depths deeper than 15 meters.[10]

Reef sites and lagoons within Western Province were surveyed in 2014 near Gizo, Munda, Marovo Lagoon and Nono Lagoon, both located in the New Georgia Islands. These areas had an average Live Coral Cover (LCC) ranging from 18 to 49%. The sites with the highest LCC in the Western Province and second highest in the Solomons were on the exposed side of the fringing reef near Marovo Lagoon measuring an average of 49% LCC. The exposed side of the fringing reef of Marovo Lagoon had an average of 38% LCC. The sites with the lowest live coral cover were found near Munda with an average of 18% LCC.[10] The exposed side of the fringing reef of Marovo Lagoon was dominated by Acropora, followed by Porites, Montipora, Millepora, and Echinopora. Munda was dominated by Acropora, followed by Porites, Montipora and Agariciidae.[10]

Nono Lagoon had an average overall LCC of 32%; with individual sites ranging from 20% to 50% LCC. The lagoon floor cover included leather corals, sponges, and other soft corals such as (Sinularia and Sacrophotons). The algal community within Nono Lagoon was dominated by crustose coralline algae which accounted for 47% of the total algae observed, with the next most dominant algae being turf algae accounting for 29% of the total algae.[10]

The coral diversity in the Western Province was evenly spread among common reef-building genera including Porites, Acropora, Montipora, Pocillopora, Pocillopora, Turbinaria and Millepora (hydrocorals). Isopora was one of the most abundant coral genera in the reefs off Gizo.[10]

Reef sites within Temotu Province were surveyed in 2014 around the Reef Islands, Utupua, Vanikoro and Tinakula and were identified as having some of the highest coral diversity when compared to the other sites surveyed in the Solomons. The Reef Islands are small, uplifted coral islands with an average of 31% LCC. These reefs have the highest percentage of erect coralline algae of all the areas surveyed in the Solomons and are abundant with Halimeda (green macroalgae) that accounted for 38% of the total algae measured. Crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci), were found on the reefs in numbers that indicated an active outbreak was occurring.[10] Vanikoro and Utupua are both small atolls found within the Temotu province that had relatively high live coral cover ranging from 42% to 44% respectively. Utupua had an average of 38 of algae of its reefs present, dominated by erect coralline algae 44% coverage of the reef system. Tinakula had lower levels of live coral cover as the volcano of Tinakula had erupted in 2012 so that there was an essentially new reef system beginning to form around the half of the island's reef that was damaged in the eruption. The Reef Islands and Utupua were dominated by Acropora and Porites. Tinakula was dominated by Acropora, Porites, Montipora and Millepora.[10] Vanikoro was also dominated by crustose coralline algae at 32%, however, there was a notable amount of erect coralline algae, particularly Halimeda, accounting for 21% of the total algae observed. A total of 40 different genera were observed at Vanikoro, which was dominated by Acropora, followed by Porites.[10]

Reef sites and lagoons within Isabel Province were surveyed in 2014 around Kerehikapa and Sikopo within the boundaries of the Arnavon Community Marine Conservation Area, as well as the area around Malakobi, which lies outside the conservation area. The site at Kerehikapa had an average of 51% LCC, which was the highest average live coral cover of all areas surveyed in the Solomons. One site had the highest overall with 69% LCC. Algae accounted for an average of 30% around Kerehikapa and was composed predominately of crustose coralline algae and turf algae. Kerehikapa was dominated by Acropora, followed by Porites. These two dominant genera accounted for over 40% of the coral observed at this site.[10]

Sikopo had only 30% LCC when compared to Kerehikapa with significant amounts of coral rubble and very little reef structure, which may have been damage caused by the tsunami that struck Isabel Province in April 2007. The dominant genera around Sikopo were Acropora and Montipora, with Cyphastrea at greater levels as compared to other regions of the Solomons.[10] The survey outside of the conservation area at Malakobi identified live coral cover ranged drastically from 8-45%. The average algal cover of 52% was evenly spread among crustose coralline algae, erect coralline algae, macroalgae and turf algae. Malakobi was dominated by Acropora, Isopora and Porites.[10]

Threats to reefs and marine ecosystems

The reefs in the Solomons are exposed to the effects of pollution and over-utilisation of the reef resources by the residents of the islands,[5] and are facing detrimental effects on them due to a variety of factors that are the consequence of Climate Change such as: bleaching; an increased number of destructive tropical cyclones and the potential threat of ocean acidification that would be the result of a lowered pH of ocean waters caused by increased carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere, which results in more CO2 dissolving into the ocean.

There are a variety of human activities that are threats to reefs and marine ecosystems, including: Blast fishing using dynamite; the harvesting of coral for lime production for betel nut chewing; mining of corals for construction purposes (e.g., building of seawalls and other structures); and fishing of species that are important in maintaining the functioning of the reef ecosystem.[8] The forms of pollution include: sewage and waste from houses or factories, such as the processing of fish; sedimentation from run-off following removal of trees through logging in the forests; and plastics and other non-degradable refuse entering the ocean.[1][14][26][27]

Bleaching

There was a 36-month bleaching event on the reefs of the Solomons in 2014–2017.[6] The bleaching was a consequence of an increase in ocean temperatures that happened during the El Niño events. Bleaching events can alter the community composition of coral reefs by changing the relative abundance of corals based on the susceptibility of different species of corals to bleaching-induced mortality. Branching corals such as Acropora (staghorn corals), which tend to be more susceptible to bleaching-induced mortality.[6]

Bleaching is a process that expels the photosynthetic algae from the corals' "stomachs" or polyps.[28] This algae is called zooxanthellae. It is vital to the reef's life because it provides the coral with nutrients; it is also responsible for the color.[29] The process is called bleaching because when the algae is ejected from the coral reef the animal loses its pigment. Zooxanthella densities are continually changing; bleaching is an extreme example of what naturally happens.[30]

Surveys in 2016 identified that the reefs around New Georgia Island and Kolombangara Island in Western Province had substantially survived the thermal anomalies that caused extensive coral bleaching in other parts of the Indo-Pacific as the result of heat stress when water temperatures were recorded as high as 30 °C (86 °F; 303 K), even down as far as 25 metres (82.02 ft) during an El Niño event.[31]

The survey of reefs in 2018 at 13 sites in the Western Province, and at 4 islands (Mbabanga, Tetepare, Uepi, Gatokae) in the New Georgia Islands, concluded that reef-building capacity (percentage cover of reef building organisms: hard corals and coralline algae), as the indicator of the resilience of reefs to large-scale disturbances, was high across the sites.[6] The average percent cover of active reef builders at these sites in Western Province (44.6%) was comparable to that of remote uninhabited islands in the Central Pacific (45.2%), and substantially greater than inhabited islands (27.3%) in the same region.[6] The conclusion reached was that the surveyed reefs in the Western Province remain healthy and functional in the face of recent global and local stressors. The conclusion was that the relatively healthy status of the reefs likely reflects local variation in seawater temperature and low levels of bleaching stress.[6]

However, in January 2021, the reefs around Marovo Lagoon including the Zaira Resource Management Area on the western coast of Vangunu Island, and New Georgia Island were reported as suffering a widespread coral bleaching event.[31]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kool, J., T. Brewer, M. Mills, and R. Pressey. (2010). Ridges to Reefs Conservation Plan for Solomon Islands (Report). Townsville: ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies. https://www.academia.edu/1919368. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ Turak, E. edited by Green, A., P. Lokani, W. Atu, P. Ramohia, P. Thomas and J. Almany (2006). Solomon Islands Marine Assessment: Technical report of survey conducted May 13 to June 17, 2004. TNC Pacific Island Countries Report No. 1/06 (Report). DC: World Resources Institute. pp. 65–109. https://www.conservationgateway.org/Documents/SolomonIslandsMarineAssessmentReport-Full.pdf. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ Veron, J. E. N., and E. Turak, edited by Green, A., P. Lokani, W. Atu, P. Ramohia, P. Thomas and J. Almany (2006). Solomon Islands Marine Assessment: Technical report of survey conducted May 13 to June 17, 2004. TNC Pacific Island Countries Report No. 1/06 (Report). DC: World Resources Institute. https://www.conservationgateway.org/Documents/SolomonIslandsMarineAssessmentReport-Full.pdf. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ Doubilet, David. "Ultra Marine: In far eastern Indonesia, the Raja Ampat islands embrace a phenomenal coral wilderness". National Geographic, September 2007. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2007/09/indonesia/doubilet-text.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Burke, L., Reytar, K., Spalding, M., Perry, A., Knight, M., Kushner, B., Starkhouse, B., Waite, R. and White, A. (2012). Reefs at Risk Revisited in the Coral Triangle (Report). DC: World Resources Institute. https://pdf.wri.org/reefs_at_risk_revisited_coral_triangle.pdf. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Denley D., Metaxas A., Scheibling R. (2020). "Subregional variation in cover and diversity of hard coral (Scleractinia) in the Western Province, Solomon Islands following an unprecedented global bleaching event". PLOS ONE 15 (11): e0242153. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0242153. PMID 33175873. Bibcode: 2020PLoSO..1542153D.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Sulu R., Boso, D., Vave-Karamui A., Mauli S. (2014). State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands (Report). Asian Development Bank. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.1991.7280. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281947995. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Sulu, Reuben & C., Hay & Ramohia, P. & Lam, M. (2003). The status of Solomon Islands coral reefs (Report). Centre IRD de Nouméa. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/282170987. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 Ceccarelli DM, Wini-Simeon, Sullivan, Wendt, Vave-Karamui, Masu, Nicolay-Grosse Hokamp, Davey, Fernandes (2018). Biophysically Special, Unique Marine Areas of the Solomon Islands (Report). MACBIO, (GIZ, IUCN, SPREP), Suva. ISBN 978-0-9975451-6-6. http://macbio-pacific.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/SUMA-Solomon-Islands-Digital-High-Resolution.pdf. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ 10.00 10.01 10.02 10.03 10.04 10.05 10.06 10.07 10.08 10.09 10.10 10.11 10.12 Carlton, R., Dempsey, A., Lubarsky, K., Akao, I., Faisal, M., and Purkis, S. (2020). Global Reef Expedition: Solomon Islands (Final Report) (Report). The Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation. ISBN 978-0-9975451-6-6. https://www.livingoceansfoundation.org/publication/global-reef-expedition-solomon-islands-final-report/. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ Coleman P.J. (July 1970). "Baseline marine biological surveys of the Phoenix Islands as Part of the Melanesian Re-entrant, Southwest Pacific". Pacific Science 24: 289–314. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/4058/1/v24n3-289-314.pdf. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ Stoddart, D. R. (28 August 1969). "Geomorphology of the Solomon Islands Coral Reefs". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 255 (800): 355–382. doi:10.1098/rstb.1969.0016. Bibcode: 1969RSPTB.255..355S.

- ↑ Woodroffe, C. D. & Biribo, N. (2011). "Atolls". in D. Hopley. Encyclopedia of Modern Coral Reefs: structure, form and process. The Netherlands: Springer. pp. 51–71. https://ro.uow.edu.au/scipapers/1060.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 ADB project officers (2014). Regional State of the Coral Triangle - Coral Triangle Marine Resources: Their Status, Economies, and Management (Report). Asian Development Bank. https://solomonislands-data.sprep.org/system/files/Regional-State-of-the-Coral-Triangle-Report.pdf. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ Erickson, Jon (2003). Marine Geology: Exploring the New Frontiers of the Ocean. Facts on File, Inc.. pp. 126–128. ISBN 978-0-8160-4874-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=CYCiFksxZckC&pg=PA126.

- ↑ McNeil, F. S. (1954). "Organic reefs and banks and associated detrital sediments". American Journal of Science 252 (7): 385–401. doi:10.2475/ajs.252.7.385. Bibcode: 1954AmJS..252..385M. "on p. 396 McNeil defines atoll as an annular reef enclosing a lagoon in which there are no promontories other than reefs and composed of reef detritus".

- ↑ Joshua Calder (2006). "Largest Coral Atoll in the world". World Island Information. http://www.worldislandinfo.com/MISINFORMATION.htm.

- ↑ "Historical Photographs of Malaita". University of Queensland. http://www.uq.edu.au/hprc/beattie-malaita.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Jan van der Ploeg, Meshach Sukulu, Hugh Govan, Tessa Minter and Hampus Eriksson (3 September 2020). "The people of the artificial island of Foueda, Lau Lagoon, Malaita, Solomon Islands: Traditional fishing methods, fisheries management and the roles of men and women in fishing". Sustainability 12 (17): 7225. doi:10.3390/su12177225.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Bennie Buga and Veikila Vuki (July 2012). "Sinking Islands, Drowned Logic; Climate Change and Community-Based Adaptation Discourses in Solomon Islands". SPC Women in Fisheries Information Bulletin #22. https://spccfpstore1.blob.core.windows.net/digitallibrary-docs/files/1a/1aaa84b03a9020b6ddbcda77f1c284d5.pdf?sv=2015-12-11&sr=b&sig=snbEpzdX4mcTvlAyLjgJdmSTScBhO%2F61Za1n5adodyg%3D&se=2021-10-10T22%3A35%3A09Z&sp=r&rscc=public%2C%20max-age%3D864000%2C%20max-stale%3D86400&rsct=application%2Fpdf&rscd=inline%3B%20filename%3D%22WIF22_42_Buga.pdf%22.

- ↑ Stanley, David (1999). South Pacific Handbook. Moon South Pacific. p. 895.

- ↑ Turak, E. edited by Green, A., P. Lokani, W. Atu, P. Ramohia, P. Thomas and J. Almany (2006). Solomon Islands Marine Assessment: Technical report of survey conducted May 13 to June 17, 2004. TNC Pacific Island Countries Report No. 1/06 (Report). DC: World Resources Institute. pp. 64–109. https://www.conservationgateway.org/Documents/SolomonIslandsMarineAssessmentReport-Full.pdf. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ Veron, J. E. N., and E. Turak, edited by Green, A., P. Lokani, W. Atu, P. Ramohia, P. Thomas and J. Almany (2006). Solomon Islands Marine Assessment: Technical report of survey conducted May 13 to June 17, 2004. TNC Pacific Island Countries Report No. 1/06 (Report). DC: World Resources Institute. pp. 35–63.

- ↑ Allen, G. R., edited by Green, A., P. Lokani, W. Atu, P. Ramohia, P. Thomas and J. Almany (2006). Solomon Islands Marine Assessment: Technical report of survey conducted May 13 to June 17, 2004. TNC Pacific Island Countries Report No. 1/06 (Report). DC: World Resources Institute. pp. 196–267.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Peter Ramohia, edited by Green, A., P. Lokani, W. Atu, P. Ramohia, P. Thomas and J. Almany (2006). Solomon Islands Marine Assessment: Technical report of survey conducted May 13 to June 17, 2004. TNC Pacific Island Countries Report No. 1/06 (Report). DC: World Resources Institute. pp. 339–343.

- ↑ Simon Albert, Ian Tibbetts, James Udy (2013). Solomon Islands Marine Life (Report). The University of Queensland, Brisbane. ISBN 978-1-74272-098-2. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:322975. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ van der Ploeg J, Jupiter S, Hughes A, Eriksson H, Boso D and Govan H. (2020). Coral reef conservation in Solomon Islands: Overcoming the policy implementation gap (Report). Penang, Malaysia: WorldFish; Honiara, Solomon Islands: Wildlife Conservation Society and Locally Managed Marine Area network. Program Report: 2020-39. https://library.sprep.org/sites/default/files/2021-01/coral-reef-conservation-solomon-islands.pdf. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ Blackman, Stuart (September 2004). "Life's a bleach". The Scientist 18 (18). Gale A123079900. https://www.the-scientist.com/briefs/lifes-a-bleach-49546.

- ↑ Hughes, T. P.; Baird, AH; Bellwood, DR; Card, M; Connolly, SR; Folke, C; Grosberg, R; Hoegh-Guldberg, O et al. (15 August 2003). "Climate Change, Human Impacts, and the Resilience of Coral Reefs". Science 301 (5635): 929–933. doi:10.1126/science.1085046. PMID 12920289. Bibcode: 2003Sci...301..929H.

- ↑ Eric Borneman (2008). "Reefkeeping". Reefkeeping Magazine. http://www.reefkeeping.com/issues/2004-09/eb/.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Widespread Bleaching Spotted in Solomon Islands Coral Reefs". Wildlife Conservation Society. 5 March 2021. https://newsroom.wcs.org/News-Releases/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/15878/Widespread-Bleaching-Spotted-in-Solomon-Islands-Coral-Reefs.aspx.

KSF

KSF