Kem Kem Group

Topic: Earth

From HandWiki - Reading time: 17 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 17 min

| Kem Kem Group Stratigraphic range: Cenomanian[1] ~100–95 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Geological group |

| Sub-units | Douira Formation, Gara Sbaa Formation |

| Underlies | Cenomanian-Turonian limestone platform (Akrabou Formation) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Sandstone |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 32°50′N 4°50′W / 32.833°N 4.833°W |

| Paleocoordinates | [ ⚑ ] 18°48′N 4°06′W / 18.8°N 4.1°W |

| Region | Er Rachidia, Tafilalt |

| Country | Morocco |

| Extent | central and eastern Morocco north and south of the Pre-African Trough |

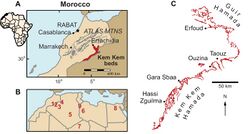

The Kem Kem Group (commonly known as the Kem Kem beds[1]) is a geological group in the Kem Kem region of eastern Morocco, whose strata date back to the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous. Its strata are subdivided into two geological formations, with the lower Ifezouane Formation and the upper Aoufous Formation used for the strata on the eastern side of the Atlas Mountains (Tinghir), with the Gara Sbaa Formation and Douira Formation used in the southern Tafilalt region.[2] It is exposed on an escarpment along the Algeria–Morocco border.

The unit unconformably overlies Paleozoic marine units of Cambrian, Silurian and Devonian ages and is itself capped by limestone platform rock of Cenomanian-Turonian age. It primarily consists of freshwater and estuarine deltaic deposits. The lower Gara Sbaa Formation primarily consists of fine and medium grained sandstone, while the Douira Formation consists of fining-upward, coarse-to-fine grained sandstones intercalated with siltstones, variegated mudstones, and occasional thin gypsiferous evaporites.[1]

Dinosaur remains are among the fossils that have been recovered from the group.[3] Recent fossil evidence in the form of isolated large abelisaurid bones and comparisons with other similarly aged deposits elsewhere in Africa indicates that the fauna of the Kem Kem Group (specifically in regard to the numerous predatory theropod dinosaurs) may have been mixed together due to the harsh and changing geology of the region, when in reality they would likely have preferred separate habitats and likely would have been separated by millions of years.[4]

Although preserving a freshwater habitat located near a river delta (with some estuarine influence that increased over time as the sea level rose), the Kem Kem deposits were quickly submerged by the sea during the Cenomanian-Turonian boundary event, and are thus overlaid by the marine deposits of the younger latest Cenomanian and early-mid Turonian-aged Akrabou Formation, which was formerly also considered a member of the Kem Kem Group, but has been differentiated from it in more recent studies due to their differing paleoenvironments.[1][5]

Vertebrate paleofauna

Cartilaginous fish

| Cartilaginous fish | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

| Acrodontidae indet.[1] | Indeterminate | Members of Hybodontoidea | |||

| Bahariyodon[1] | B. bartheli | A member of Hybodontoidea | |||

| Cenocarcharias[1] | C. tenuiplicatus | One tooth[1] | A member of the family Cretoxyrhinidae | ||

| Distobatus[1] | D. nutiae | A member of Hybodontoidea | |||

| Haimirichia[1] | H. amonensis | One tooth[1] | A mackerel shark | ||

| Marckgrafia[1] | M. lybica | 13 teeth[1] | A member of Batoidea | ||

| Onchopristis | O. numida[6] | A rajiform ray[7] |  | ||

| Peyeria[1] | P. libyca | Three teeth[1] | A sawfish. Might be a junior synonym of Onchopristis numida. | ||

| Tribodus[1] | T. sp. | A member of Hybodontoidea | |||

Ray-finned fish

| Ray-finned fish | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

| Adrianaichthys[1] | A. pankowskii | Isolated scales[8] and two skulls[9] | A member of Lepisosteiformes. Originally described as a species of Lepidotes, but subsequently transferred to a separate genus.[10] |

| |

| Afrocascudo[11] | A. saharaensis | A neopterygiian fish, either an ancient loricariid catfish or a juvenile obaichthyid lepisosteiform.[12] | |||

| Agassizilia[13] | A. erfoudina | Possibly a member of the family Pycnodontidae. | |||

| Agoultichthys[1] | A. chattertoni | A long-bodied member of Actinopterygii of uncertain phylogenetic placement. Might be a member of the family Macrosemiidae[14] or Ophiopsiellidae.[15] | |||

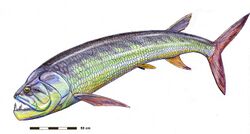

| Aidachar | A. pankowskii | A member of Ichthyodectiformes | |||

| Bartschichthys[1] | B. sp. | Isolated pinnulae (spines that support each dorsal finlet)[1] | A cladistian | ||

| Bawitius | cf. B. sp. | Isolated scales and jaw fragments[8] | A cladistian | ||

| Calamopleurus[1] | C. africanus | A partial skull[1] | A member of Amiiformes | ||

| Concavotectum[1] | C. moroccensis | A member of Tselfatiiformes | |||

| Dentilepisosteus[1] | D. kemkemensis | A member of Lepisosteiformes | |||

| Diplomystus[1] | D. sp. | A deep-bodied teleost belonging to the group Clupeomorpha | |||

| Diplospondichthys[1] | D. moreaui | A member of Actinopterygii of uncertain phylogenetic placement, possibly a teleost | |||

| Erfoudichthys[1] | E. rosae | Isolated skull[1] | A small-bodied teleost of unknown affinity | ||

| Neoproscinetes[13] | N. africanus | A member of the family Pycnodontidae | |||

| Obaichthys | O. africanus | Isolated scales[8] | A member of Lepisosteiformes | ||

| Oniichthys | O. falipoui | Near complete skeleton including skull[8] | A member of Lepisosteiformes | ||

| Palaeonotopterus[1] | P. greenwoodi | A member of Osteoglossomorpha | |||

| Serenoichthys[1] | S. kemkemensis | Several articulated skeletons[1] | A small cladistian | ||

| Spinocaudichthys[1] | S. oumtkoutensis | An elongate freshwater acanthomorph | |||

| Stromerichthys | S. aethiopicus | ||||

| Sudania[1] | S. sp. | An isolated pinnula[1] | A cladistian | ||

Lobe-finned fish

| Lobe-finned fish | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Material | Notes | Images |

| Arganodus | A. tiguidiensis | A lungfish |

| ||

| Axelrodichthys[16] | A.? lavocati | A mawsoniid coelacanth; this species was previously assigned to Mawsonia, and its generic assignment is still not certain[17] | |||

| Neoceratodus | N. africanus | A Neoceratodid lungfish | |||

Amphibians

| Amphibians | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

| Anura indet.[18] | Indeterminate | Douira Formation | Incomplete left ilium | |||

| Cretadhefdaa[18] | C. taouzensis | Douira Formation | Posterior portion of the skull, incomplete squamosal, incomplete maxilla, three incomplete presacral vertebrae, one incomplete sacral vertebra | A neobatrachian frog with possible hyloid affinities. | ||

| cf. Kababisha[19] | Indeterminate | A salamander belonging to the family Sirenidae | ||||

| ?Neobatrachia indet.[18] | Indeterminate | Douira Formation | Incomplete humerus | A frog, possibly a member of Ranoidea. | ||

| Oumtkoutia[19] | O. anae | A frog belonging to the family Pipidae | ||||

Lizards and snakes

Template:Paleobiota-key-compact

| Lizards and snakes reported from the Continental Red Beds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

B. hogreli[20] |

A polyglyphanodontid lizard. |

|||||

| Jeddaherdan[21] |

J. aleadonta |

Partial mandible with teeth. |

An iguanian belonging to the group Acrodonta, possibly a relative of the uromastycine agamids. Argued by Vullo et al. (2022) to actually come from Quaternary beds, and to be based on a fossil material of a member of the genus Uromastyx.[22] |

|||

|

L. ragei[23] |

Two isolated trunk vertebrae |

An early snake. |

||||

|

Madtsoiidae indet.[19] |

Indeterminate |

Vertebrae[1] |

An early snake. |

|||

|

?Nigerophiidae indet.[19] |

Indeterminate |

Dorsal vertebrae[1] |

An early snake. |

|||

|

Norisophis[24] |

N. begaa[24] |

One posterior and two mid-trunk vertebrae |

A stem-snake. |

|||

|

Indeterminate[24] |

A mid-trunk vertebra | |||||

|

cf. S. libycus |

Vertebrae[1] |

An early snake. |

||||

Plesiosaurs

| Plesiosaurs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

| Leptocleididae cf. Leptocleidus[25] | indeterminate | |||||

Turtles

| Turtles reported from the Continental Red Beds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | |

|

Dirqadim |

D. schaefferi |

A Euraxemydid | ||||

|

G. emringeri |

A Cearachelyin | |||||

| G. whitei | ||||||

|

Hamadachelys |

H. escuilliei |

|||||

Crocodylomorphs

A tooth enamel identified as cf. Sarcosuchus was discovered from the Ifezouane Formation.[26]

| Crocodylomorphs reported from the Continental Red Beds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

A. witmeri |

"Partial braincase of a large individual with skull roof, temporal, and occipital regions."[27] |

An aegyptosuchid that may be a synonym of Laganosuchus.[1] |

| |||

|

A. taouzensis |

Paired mandibles and a partial right mandible |

A peirosaurid. | ||||

|

A. rattoides |

Douira Formation | |||||

|

E. cherifiensis |

|

A pholidosaurid. The material may represent two different species.[1] | ||||

|

H. rebouli |

|

A peirosaurid. | ||||

|

K. auditorei |

Errachidia Province, Morocco[29] |

Known from an isolated caudal vertebra.[29] |

Initially thought to be a neotheropod,[29] but subsequently discovered to be an indeterminate crocodyliform.[30] | |||

| L. thaumastos | ||||||

|

L. sigogneaurusselae |

Anterior portion of a rostrum with mandible, with an almost complete dentition[31] |

|||||

Dinosaurs

Indeterminate lithostrotian remains once misattributed to the Titanosauridae are present in the province of Ksar-es-Souk, Morocco.[3] Template:Paleobiota-key-compact

Ornithischians

| Ornithischians reported from the Continental Red Beds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

Indeterminate |

Douira Formation |

An isolated tooth.[1] |

A probable ankylosaur[32] | |||

|

Indeterminate |

Douira Formation |

A large, clover-shaped, three-toed footprint.[1] |

Comparable in size and shape to tracks typically attributed to Iguanodon.[33] | |||

Sauropods

| Sauropods reported from the Continental Red Beds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

R. garasbae |

Ksar-es-Souk province, Morocco.[3] |

Gara Sbaa Formation |

A rebbachisaurid. |

| ||

|

Indeterminate |

Anterior dorsal vertebra, partial right ischium[34] |

The vertebra might belong to a basal titanosaurian, possibly distinct from Aegyptosaurus and Paralititan.[34] The ischium is not identifiable beyond Somphospondyli; it preserves numerous grooves and pits which might be feeding traces left by a very large non-avian theropod.[34] | ||||

|

Indeterminate |

|

Isolated teeth, caudal vertebrae, a partial humerus, a tarsal bone and the proximal end of an ulna.[1] |

Fossil material of one or more titanosaurian sauropods. Some fossils are indicative of large body size comparable to Paralititan stromeri.[1] | |||

Theropods

| Theropods reported from the Continental Red Beds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

Indeterminate |

Isolated teeth.[36][37] |

Abelisaurid material belonging to one or two distinct taxa.[1] |

| |||

|

C. saharicus[3] |

Ksar-es-Souk province, Morocco.[3] | Douira Formation | Partial skull, including braincase, nasals, postorbitals, jugals, left lacrimal and right maxilla with most teeth.[39] |

A carcharodontosaurid theropod. | ||

| Carcharodontosauridae[40] | Indeterminate | Southeast of Taouz, Errachidia Province | Ifezouane Formation | partial maxilla and partial jugal | A carcharodontosaurid theropod different from C. saharicus | |

|

D. agilis |

Gara Sbaa Formation |

"Partial skeleton, isolated limb elements."[41] |

A noasaurid ceratosaurian, May be synonymous with Bahariasaurus. | |||

|

Indeterminate |

Isolated teeth.[36] |

Originally described as teeth of indeterminate dromaeosaurids. Hendrickx et al. (2024) reinterpreted this fossil material as teeth of abelisauroid theropods, including noasaurids and juvenile abelisaurids.[37] | ||||

|

cf. Elaphrosaurus |

Indeterminate |

Ksar-es-Souk province, Morocco.[3] |

Fossils previously referred to cf. Elaphrosaurus are actually indeterminate theropod remains. | |||

|

Indeterminate |

||||||

| "Osteoporosia"[42] | "O. gigantea"[42] | A tooth and a possible neural arch from another specimen.[42] | A theropod, possibly synonymous with Sauroniops.[43] | |||

|

Indeterminate |

An isolated cervical vertebra.[44] |

An indeterminate saurischian. | ||||

|

S. pachytholus |

Ifezouane Formation |

"An isolated and almost complete left frontal,[46] and a possible tooth and neural arch from two other specimens."[43] |

A carcharodontosaurid thought to be distinct from Carcharodontosaurus,[45][46] considered a nomen dubium by Kellerman et al.[47] | |||

| Sigilmassasaurus | S. brevicollis | Tafilalt Oasis region, Morocco. | Kem Kem Formation | A single neck vertebrae. | A controversial spinosaurid theropod. | |

|

S. aegyptiacus |

Ksar-es-Souk province, Morocco.[3] | Douira Formation | Partial skeleton, including parts of the skull, neck, torso, and most of the tail and hind limbs.[48]

Numerous isolated bones. |

A spinosaurid theropod. | ||

| Averostra indet | Indeterminate | Tooth | Said to belong to either a non-abelisaurid ceratosaur or a megaraptoran. [37] | |||

| Abelisauroidea indet. | Indeterminate | Douira Formation [49] | Pedal Ungual [50] | An indeterminate abelisauroid, known from a 7 cm long pedal ungual. Likely an abelisaurid or noasaurid. | ||

Pterosaurs

| Pterosaurs of the Kem Kem Beds | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Abundance | Notes | Images |

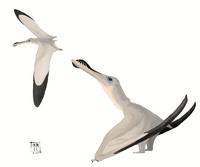

|

A. zouhri[51] |

Takmout | Ifezouane Formation |

A fragment of bone interpreted as a fragment of anterior mandibular symphysis,[52] and additional jaw fragments that pertain to the rostrum as well as indeterminate jaw fragments.[2] |

A tapejarid pterosaur. Originally believed to belong to either the family Thalassodromidae[53] or an additional specimen of Alanqa saharica.[54] |

| |

| Akharhynchus[55] | A. martilli | Tafilalt | Ifezouane Formation | A fragment of the anterior part of the premaxillae | A tropeognathine anhanguerian. | |

|

A. saharica[53] |

Ifezouane Formation | The holotype is a mandibular symphysis, of different parts of the jaw | A pterosaur of uncertain phylogenetic placement, probably an azhdarchid.[2] | |||

|

A. cf. piscator[56] |

upper Ifezouane Formation |

Partial mandibular symphysis[56] |

||||

|

Apatorhamphus[57] |

A. gyrostega[57] |

Ifezouane Formation |

Partial rostrum and mandible, with additional referred jaw fragments[2] |

A possible chaoyangopterid azhdarchoid pterosaur.[57] Originally believed to be a possible pteranodontid,[53] a possible dsungaripterid,[58] a possible non-azhdarchid azhdarchoid or nyctosaurid,[58] or a specimen of Alanqa saharica.[54] | ||

|

Azhdarchidae indet.[58][2] |

Indicative of multiple taxa.[58] Some of these vertebrae may pertain to Alanqa saharica.[54][59] | |||||

|

Azhdarchoidea indet. |

"Jaw morphotype A"[2] | Two jaw fragments[2] | Different from all named Kem Kem pterosaur taxa[2] | |||

| "Jaw morphotype B"[2] | Partial mandible fragment[2] | Probably had a similarly long jaw to Leptostomia[2] | ||||

| "Jaw morphotype C"[2] | Partial jaw fragments[2] | May belong to Apatorhamphus or Xericeps[2] | ||||

|

Indeterminate[2] |

Five cervical vertebrae, a scapulocoracoid, two humeri, two ulnae, a metacarpal IV, and a tibiotarsus[2] | |||||

| Coloborhynchus[56] | C. sp. A.[56] | Hassi El Begaa | Premaxillae fragment[56] | Possibly a specimen of Nicorhynchus fluviferox.[60] | ||

|

L. begaaensis[61] |

Aferdou N' Chaft |

upper Ifezouane Formation |

Partial rostrum and partial mandibular synthesis[61] |

A small, long-beaked pterosaur, likely a member of Azhdarchoidea.[61] | ||

|

Possibly Aferdou N'Chaft, Hassi El Begaa[60] |

Ifezouane Formation |

An anterior portion of the rostrum.[60] |

Originally described as a species of Coloborhynchus[62] but subsequently transferred to the genus Nicorhynchus. | |||

|

O. cf. simus.[56] |

upper Ifezouane Formation |

Premaxillae fragment[56] |

||||

|

S. moroccensis[63] |

Anterior part of a rostrum |

Classified by some authors as a species belonging to the genus Coloborhynchus.[53] | ||||

| Xericeps | X. curvirostra | Aferdou N'Chaft | Ifezouane Formation | Mandibular symphysis and partial mandible[2] | An indeterminate azhdarchoid, possibly a chaoyangopterid.[2] | |

See also

- Aoufous Formation, which lies within the Kem Kem Beds

- List of dinosaur-bearing rock formations

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 1.27 1.28 1.29 1.30 1.31 1.32 1.33 1.34 1.35 1.36 1.37 1.38 1.39 1.40 1.41 1.42 1.43 1.44 1.45 1.46 1.47 Ibrahim, N.; Sereno, P.C.; Varricchio, D.J.; Martill, D.M.; Dutheil, D.B.; Unwin, D.M.; Baidder, L.; Larsson, H.C.E. et al. (2020). "Geology and paleontology of the Upper Cretaceous Kem Kem Group of eastern Morocco". ZooKeys (928): 1–216. doi:10.3897/zookeys.928.47517. PMID 32362741. Bibcode: 2020ZooK..928....1I.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 Smith, Roy E.; Ibrahim, Nizar; Longrich, Nicholas; Unwin, David M.; Jacobs, Megan L.; Williams, Cariad J.; Zouhri, Samir; Martill, David M. (2023-02-04). "The pterosaurs of the Cretaceous Kem Kem Group of Morocco" (in en). PalZ 97 (3): 519–568. doi:10.1007/s12542-022-00642-6. ISSN 1867-6812. Bibcode: 2023PalZ...97..519S.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Late Cretaceous, Africa)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 604-605. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Alfio Alessandro Chiarenza; Andrea Cau (2016). "A large abelisaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from Morocco and comments on the Cenomanian theropods from North Africa". PeerJ 4. doi:10.7717/peerj.1754. PMID 26966675.

- ↑ Cavin, L.; Tong, H.; Boudad, L.; Meister, C.; Piuz, A.; Tabouelle, J.; Aarab, M.; Amiot, R. et al. (2010-07-01). "Vertebrate assemblages from the early Late Cretaceous of southeastern Morocco: An overview". Journal of African Earth Sciences 57 (5): 391–412. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2009.12.007. ISSN 1464-343X. Bibcode: 2010JAfES..57..391C. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1464343X09002404.

- ↑ Greenfield, T. (2021). "Corrections to the nomenclature of sawskates (Rajiformes, Sclerorhynchoidei)". Bionomina 22 (1): 39–41. doi:10.11646/bionomina.22.1.3.

- ↑ Villalobos-Segura, Eduardo; Kriwet, Jürgen; Vullo, Romain; Stumpf, Sebastian; Ward, David J; Underwood, Charlie J (2021-10-01). "The skeletal remains of the euryhaline sclerorhynchoid †Onchopristis (Elasmobranchii) from the 'Mid'-Cretaceous and their palaeontological implications". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 193 (2): 746–771. doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa166. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Cavin, Lionel; Boudad, Larbi; Tong, Haiyan; Läng, Emilie; Tabouelle, Jérôme; Vullo, Romain (2015). "Taxonomic Composition and Trophic Structure of the Continental Bony Fish Assemblage from the Early Late Cretaceous of Southeastern Morocco" (in en). PLOS ONE 10 (5). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125786. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 26018561. Bibcode: 2015PLoSO..1025786C.

- ↑ Forey, Peter L.; López-Arbarello, Adriana; MacLeod, Norman (2011). "A New Species of Lepidotes (Actinopterygii: Semiontiformes) from the Cenomanian (Upper Cretaceous) of Morocco". Palaeontologia Electronica 14 (1): 7A–12. https://palaeo-electronica.org/2011_1/239/239.pdf.

- ↑ François J. Meunier; René-Paul Eustache; Didier Dutheil; Lionel Cavin (2016). "Histology of ganoid scales from the early Late Cretaceous of the Kem Kem beds, SE Morocco: systematic and evolutionary implications". Cybium 40 (2): 121–132. doi:10.26028/cybium/2016-402-003. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303018377.

- ↑ Brito, P. M.; Dutheil, D. B.; Gueriau, P.; Keith, P.; Carnevale, G.; Britto, M.; Meunier, F. J.; Khalloufi, B. et al. (2024). "A saharan fossil and the dawn of Neotropical armoured catfishes in Gondwana". Gondwana Research 132: 103–112. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2024.04.008. Bibcode: 2024GondR.132..103B. https://serval.unil.ch/resource/serval:BIB_E3F9F6493E66.P002/REF.pdf.

- ↑ Britz, R.; Pinion, Amanda K.; Kubicek, Kole M.; Conway, Kevin W. (2024). "Comment on "A Saharan fossil and the dawn of Neotropical armoured catfishes in Gondwana" by Brito et al". Gondwana Research 133: 267–269. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2024.06.014. Bibcode: 2024GondR.133..267B.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Samuel L.A. Cooper; David M. Martill (2020). "A diverse assemblage of pycnodont fishes (Actinopterygii, Pycnodontomorpha) from the mid-Cretaceous, continental Kem Kem beds of South-East Morocco". Cretaceous Research 112. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104456.

- ↑ Alison M. Murray; Mark V. H. Wilson (2009). "A new Late Cretaceous macrosemiid fish (Neopterygii, Halecostomi) from Morocco, with temporal and geographical range extensions for the family". Palaeontology 52 (2): 429–440. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00851.x. Bibcode: 2009Palgy..52..429M.

- ↑ Martin Ebert (2018). "Cerinichthys koelblae, gen. et sp. nov., from the Upper Jurassic of Cerin, France, and its phylogenetic setting, leading to a reassessment of the phylogenetic relationships of Halecomorphi (Actinopterygii)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 38 (1). doi:10.1080/02724634.2017.1420071. Bibcode: 2018JVPal..38E0071E. https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/5990965.

- ↑ Fragoso, L.G.C.; Brito, P.; Yabumoto, Y. (2019). "Axelrodichthys araripensis Maisey, 1986 revisited". Historical Biology 31 (10): 1350–1372. doi:10.1080/08912963.2018.1454443. Bibcode: 2019HBio...31.1350C. https://figshare.com/articles/dataset/_i_Axelrodichthys_araripensis_i_Maisey_1986_revisited/6031925.

- ↑ Cavin, L.; Cupello, C.; Yabumoto, Y.; Fragoso, L.G.C.; Deesri, U.; Brito, P.M. (2019). "Phylogeny and evolutionary history of mawsoniid coelacanths". Bulletin of the Kitakyushu Museum of Natural History and Human History, Series A 17: 3–13. http://www.kmnh.jp/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/A17-3-Cavin.pdf. Retrieved 2024-04-27.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Lemierre, A.; Blackburn, D. C. (2022). "A new genus and species of frog from the Kem Kem (Morocco), the second neobatrachian from Cretaceous Africa". PeerJ 10: e13669. doi:10.7717/peerj.13699. PMID 35860040.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Jean-Claude Rage; Didier B. Dutheil (2008). "Amphibians and squamates from the Cretaceous (Cenomanian) of Morocco - A preliminary study, with description of a new genus of pipid frog". Palaeontographica Abteilung A 285 (1–3): 1–22. doi:10.1127/pala/285/2008/1. Bibcode: 2008PalAA.285....1R.

- ↑ Romain Vullo; Jean-Claude Rage (2018). "The first Gondwanan borioteiioid lizard and the mid-Cretaceous dispersal event between North America and Africa". The Science of Nature 105 (11–12). doi:10.1007/s00114-018-1588-3. PMID 30291449. Bibcode: 2018SciNa.105...61V.

- ↑ Sebastián Apesteguía; Juan D. Daza; Tiago R. Simões; Jean Claude Rage (2016). "The first iguanian lizard from the Mesozoic of Africa". Royal Society Open Science 3 (9). doi:10.1098/rsos.160462. PMID 27703708. Bibcode: 2016RSOS....360462A.

- ↑ Romain Vullo; Salvador Bailon; Yannicke Dauphin; Hervé Monchot; Ronan Allain (2022). "A reappraisal of Jeddaherdan aleadonta (Squamata: Acrodonta), the purported oldest iguanian lizard from Africa". Cretaceous Research 143: 105412. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105412. https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-03843530.

- ↑ Romain Vullo (2019). "A new species of Lapparentophis from the mid-Cretaceous Kem Kem beds, Morocco, with remarks on the distribution of lapparentophiid snakes". Comptes Rendus Palevol 18 (7): 765–770. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2019.08.004. Bibcode: 2019CRPal..18..765V.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Catherine G. Klein; Nicholas R. Longrich; Nizar Ibrahim; Samir Zouhri; David M. Martill (2017). "A new basal snake from the mid-Cretaceous of Morocco". Cretaceous Research 72: 134–141. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.12.001. Bibcode: 2017CrRes..72..134K. http://opus.bath.ac.uk/54192/1/Basal_Snake_Cretaceous_Morocco_PostReviewCleanCopyFigs.pdf.

- ↑ Bunker, G.; Martill, D. M.; Smith, R.; Zourhi, S.; Longrich, N. (2022). "Plesiosaurs from the fluvial Kem Kem Group (mid-Cretaceous) of eastern Morocco and a review of non-marine plesiosaurs". Cretaceous Research 140. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105310. Bibcode: 2022CrRes.14005310B.

- ↑ Amiot, Romain; Wang, Xu; Lécuyer, Christophe; Buffetaut, Eric; Boudad, Larbi; Cavin, Lionel; Ding, Zhongli; Fluteau, Frédéric et al. (2010). "Oxygen and carbon isotope compositions of middle Cretaceous vertebrates from North Africa and Brazil: Ecological and environmental significance". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 297 (2): 439–451. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2010.08.027. Bibcode: 2010PPP...297..439A. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0031018210005213.

- ↑ Casey M. Holliday; Nicholas M. Gardner (2012). "A New Eusuchian Crocodyliform with Novel Cranial Integument and Its Significance for the Origin and Evolution of Crocodylia". PLOS ONE 7 (1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030471. PMID 22303441. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...730471H.

- ↑ Cecily S. C. Nicholl; Eloise S. E. Hunt; Driss Ouarhache; Philip D. Mannion (2021). "A second peirosaurid crocodyliform from the Mid-Cretaceous Kem Kem Group of Morocco and the diversity of Gondwanan notosuchians outside South America". Royal Society Open Science 8 (10). doi:10.1098/rsos.211254. PMID 34659786. Bibcode: 2021RSOS....811254N.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Cau, Andrea; Maganuco, Simone (2009). "A new theropod dinosaur, represented by a single unusual caudal vertebra from the Kem Kem Beds (Cretaceous) of Morocco". Atti Soc. it. Sci. nat. Museo civ. Stor. nat. Milano 150 (II): 239–257.

- ↑ Lio, G., Agnolin, F., Cau, A. and Maganuco, S. (2012). "Crocodyliform affinities for Kemkemia auditorei Cau and Maganuco, 2009, from the Late Cretaceous of Morocco." Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali e del Museo di Storia Naturale di Milano, 153 (I), s. 119–126.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Jeremy E. Martin; France De Lapparent De Broin (2016). "A miniature notosuchian with multicuspid teeth from the Cretaceous of Morocco". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36 (6). doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1211534. Bibcode: 2016JVPal..36E1534M. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02124147/file/Lavocatchampsa.pdf.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Rozadilla, Sebastián; Agnolín, Federico; Manabe, Makoto; Tsuihiji, Takanobu; Novas, Fernando E. (September 2021). "Ornithischian remains from the Chorrillo Formation (Upper Cretaceous), southern Patagonia, Argentina, and their implications on ornithischian paleobiogeography in the Southern Hemisphere". Cretaceous Research 125. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104881. ISSN 0195-6671. Bibcode: 2021CrRes.12504881R.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Nizar Ibrahim; David J. Varricchio; Paul C. Sereno; Jeff A. Wilson; Didier B. Dutheil; David M. Martill; Lahssen Baidder; Samir Zouhri (2014). "Dinosaur footprints and other ichnofauna from the Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Morocco". PLOS ONE 9 (6). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090751. PMID 24603467. Bibcode: 2014PLoSO...990751I.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Matthew C. Lamanna; Yoshikazu Hasegawa (2014). "New titanosauriform sauropod dinosaur material from the Cenomanian of Morocco: implications for paleoecology and sauropod diversity in the Late Cretaceous of North Africa". Bulletin of Gunma Museum of Natural History 18: 1–19. http://www.gmnh.pref.gunma.jp/wp-content/uploads/bulletin18_3.pdf.

- ↑ Nizar Ibrahim; Cristiano Dal Sasso; Simone Maganuco; Matteo Fabbri; David M. Martill; Eric Gorscak; Matthew C. Lamanna (2016). "Evidence of a derived titanosaurian (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) in the "Kem Kem beds" of Morocco, with comments on sauropod paleoecology in the Cretaceous of Africa". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 71: 149–159. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304214496.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Ute Richter; Alexander Mudroch; Lisa G. Buckley (2013). "Isolated theropod teeth from the Kem Kem Beds (Early Cenomanian) near Taouz, Morocco". Paläontologische Zeitschrift 87 (2): 291–309. doi:10.1007/s12542-012-0153-1. Bibcode: 2013PalZ...87..291R.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Hendrickx, C.; Trapman, T. H.; Wills, S.; Holwerda, F. M.; Stein, K. H. W.; Rauhut, O. W. M.; Melzer, R. R.; Van Woensel, J. et al. (2024). "A combined approach to identify isolated theropod teeth from the Cenomanian Kem Kem Group of Morocco: cladistic, discriminant, and machine learning analyses". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 43 (4): e2311791. doi:10.1080/02724634.2024.2311791.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Robert S.H. Smyth; Nizar Ibrahim; Alexander Kao; David M. Martill (2019). "Abelisauroid cervical vertebrae from the Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Southern Morocco and a review of Kem Kem abelisauroids". Cretaceous Research 108. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2019.104330. Bibcode: 2020CrRes.10804330S.

- ↑ Brusatte, Stephen L.; Sereno, Paul C. (2007-12-12). "A new species of Carcharodontosaurus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Cenomanian of Niger and a revision of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (4): 902–916. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2007)27[902:ANSOCD2.0.CO;2]. ISSN 0272-4634. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1671/0272-4634%282007%2927%5B902%3AANSOCD%5D2.0.CO%3B2.

- ↑ Paterna, Alessandro; Cau, Andrea (2022-10-11). "New giant theropod material from the Kem Kem Compound Assemblage (Morocco) with implications on the diversity of the mid-Cretaceous carcharodontosaurids from North Africa". Historical Biology 35 (11): 2036–2044. doi:10.1080/08912963.2022.2131406. ISSN 0891-2963.

- ↑ "Table 4.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 76.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Singer (2015). JURAPARK NA TROPIE NOWYCH DINOZAURÓW Z MAROKA (Online).

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Molina-Pérez, Rubén; Larramendi, Asier; Connolly, David; Ramírez Cruz, Gonzalo Ángel; Mazzei, Sante; Atuchin, Andrey (2019-06-25). Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Theropods and Other Dinosauriformes. Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9780691190594-013. ISBN 978-0-691-19059-4. https://princetonup.degruyter.com/view/title/550250.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 B. McFeeters (2013). "Bone "taxon" B: Reevaluation of a supposed small theropod dinosaur from the mid-Cretaceous of Morocco". Kirtlandia 58: 38–41. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/284444286.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Andrea Cau; Fabio M. Dalla Vecchia; Matteo Fabbri (2012). "A thick-skulled theropod (Dinosauria, Saurischia) from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco with implications for carcharodontosaurid cranial evolution". Cretaceous Research 40: 251–260. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2012.09.002.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Andrea Cau; Fabio Marco Dalla Vecchia; Matteo Fabbri (2012). "Evidence of a new carcharodontosaurid from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 57 (3): 661–665. doi:10.4202/app.2011.0043.

- ↑ Kellermann, Maximilian; Cuesta, Elena; Rauhut, Oliver W. M. (2025-01-14). Spekker, Olga. ed. "Re-evaluation of the Bahariya Formation carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and its implications for allosauroid phylogeny" (in en). PLOS ONE 20 (1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0311096. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 39808629. Bibcode: 2025PLoSO..2011096K.

- ↑ Ibrahim, Nizar; Maganuco, Simone; Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Fabbri, Matteo; Auditore, Marco; Bindellini, Gabriele; Martill, David M.; Zouhri, Samir et al. (May 2020). "Tail-propelled aquatic locomotion in a theropod dinosaur" (in en). Nature 581 (7806): 67–70. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2190-3. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 32376955. Bibcode: 2020Natur.581...67I.

- ↑ Vecchia, Fabio Marco Dalla. Theropod pedal unguals from the Late Cretaceous (Cenomanian) of Morocco, Africa. https://www.academia.edu/1080746/Theropod_pedal_unguals_from_the_Late_Cretaceous_Cenomanian_of_Morocco_Africa.

- ↑ Souza-Júnior, André Luis de; Candeiro, Carlos Roberto dos Anjos; Vidal, Luciano da Silva; Brusatte, Stephen Louis; Mortimer, Mickey (2023-07-05). "Abelisauroidea (Theropoda, Dinosauria) from Africa: a review of the fossil record" (in en). Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia 63: e202363019–e202363019. doi:10.11606/1807-0205/2023.63.019. ISSN 1807-0205. https://revistas.usp.br/paz/article/view/177016.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 David M. Martill; Roy Smith; David M. Unwin; Alexander Kao; James McPhee; Nizar Ibrahim (2020). "A new tapejarid (Pterosauria, Azhdarchoidea) from the mid-Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Takmout, southern Morocco". Cretaceous Research 112. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104424. Bibcode: 2020CrRes.11204424M. https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/a-new-tapejarid-pterosauria-azhdarchoidea-from-the-midcretaceous-kem-kem-beds-of-takmout-southern-morocco(eb55e1bd-d84a-4126-ad63-7c500a93f57e).html.

- ↑ Peter Wellnhofer; Eric Buffetaut (1999). "Pterosaur remains from the Cretaceous of Morocco". Paläontologische Zeitschrift 73 (1–2): 133–142. doi:10.1007/BF02987987. Bibcode: 1999PalZ...73..133W.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 53.5 Ibrahim, N.; Unwin, D.M.; Martill, D.M.; Baidder, L.; Zouhri, S. (2010). "A New Pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea: Azhdarchidae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco". PLOS ONE 5 (5). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0010875. PMID 20520782. Bibcode: 2010PLoSO...510875I.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Alexander Averianov (2014). "Review of taxonomy, geographic distribution, and paleoenvironments of Azhdarchidae (Pterosauria)". ZooKeys (432): 1–107. doi:10.3897/zookeys.432.7913. PMID 25152671. Bibcode: 2014ZooK..432....1A.

- ↑ Jacobs, Megan L.; Smith, Roy E.; Zouhri, Samir (2024). "A new ornithocheirid pterosaur (Pterosauria: Ornithocheiridae) from the mid-Cretaceous Ifezouane Formation, Kem Kem Group of Morocco" (in en). Cretaceous Research 166: 106015. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2024.106015.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 56.6 56.7 56.8 Megan L. Jacobs; David M. Martill; David M. Unwin; Nizar Ibrahim; Samir Zouhri; Nicholas R. Longrich (2020). "New toothed pterosaurs (Pterosauria: Ornithocheiridae) from the middle Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Morocco and implications for pterosaur palaeobiogeography and diversity". Cretaceous Research 110. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104413. Bibcode: 2020CrRes.11004413J.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 James McPhee; Nizar Ibrahim; Alex Kao; David M. Unwin; Roy Smith; David M. Martill (2020). "A new ?chaoyangopterid (Pterosauria: Pterodactyloidea) from the Cretaceous Kem Kem beds of Southern Morocco". Cretaceous Research 110. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104410. Bibcode: 2020CrRes.11004410M. https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/a-new-chaoyangopterid-pterosauria-pterodactyloidea-from-the-cretaceous-kem-kem-beds-of-southern-morocco(78a38938-aa6d-4802-973e-d646e1e6d594).html.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 58.4 58.5 Taissa Rodrigues; Alexander W. A. Kellner; Bryn J. Mader; Dale A. Russell (2011). "New pterosaur specimens from the Kem Kem beds (Upper Cretaceous, Cenomanian) of Morocco". Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia 117 (1): 149–160. doi:10.13130/2039-4942/5967.

- ↑ Williams, Cariad J.; Pani, Martino; Bucchi, Andrea; Smith, Roy E.; Kao, Alexander; Keeble, William; Ibrahim, Nizar; Martill, David M. (2021-04-23). "Helically arranged cross struts in azhdarchid pterosaur cervical vertebrae and their biomechanical implications". iScience 24 (4). doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102338. PMID 33997669. Bibcode: 2021iSci...24j2338W.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 60.3 60.4 Borja Holgado; Rodrigo V. Pêgas (2020). "A taxonomic and phylogenetic review of the anhanguerid pterosaur group Coloborhynchinae and the new clade Tropeognathinae". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 65 (4): 743–761. doi:10.4202/app.00751.2020.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 Roy E. Smith; David M. Martill; Alexander Kao; Samir Zouhri; Nicholas Longrich (2020). "A long-billed, possible probe-feeding pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea: ?Azhdarchoidea) from the mid-Cretaceous of Morocco, North Africa". Cretaceous Research 118. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2020.104643. https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/a-longbilled-possible-probefeeding-pterosaur-pterodactyloidea-azhdarchoidea-from-the-midcretaceous-of-morocco-north-africa(4cd598bb-c55d-469e-b450-dbcbad9c22ae).html.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Jacobs, Megan L.; Martill, David M.; Ibrahim, Nizar; Longrich, Nick (March 2019). "A new species of Coloborhynchus (Pterosauria, Ornithocheiridae) from the mid-Cretaceous of North Africa". Cretaceous Research 95: 77–88. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2018.10.018. ISSN 0195-6671. Bibcode: 2019CrRes..95...77J. https://researchportal.port.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/a-new-species-of-coloborhynchus-pterosauria-ornithocheiridae-from-the-midcretaceous-of-north-africa(d0467c1b-2328-4004-8ad3-13a2d7a08bac).html.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Rodrigues, Taissa; Kellner, Alexander W. A (2008). "Review of the pterodactyloid pterosaur Coloborhynchus". Zitteliana B 28: 219–228. http://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/12017/1/zitteliana_2008_b28_15.pdf.

|

KSF

KSF