Landslide classification

Topic: Earth

From HandWiki - Reading time: 21 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 21 min

There have been known various classifications of landslides. Broad definitions include forms of mass movement that narrower definitions exclude. For example, the McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science and Technology distinguishes the following types of landslides:

- fall (by undercutting)

- fall (by toppling)

- slump

- rockslide

- earthflow

- sinkholes, mountain side

- rockslide that develops into rock avalanche

Influential narrower definitions restrict landslides to slumps and translational slides in rock and regolith, not involving fluidisation. This excludes falls, topples, lateral spreads, and mass flows from the definition.[1][2]

The causes of landslides are usually related to instabilities in slopes. It is usually possible to identify one or more landslide causes and one landslide trigger. The difference between these two concepts is subtle but important. The landslide causes are the reasons that a landslide occurred in that location and at that time and may be considered to be factors that made the slope vulnerable to failure, that predispose the slope to becoming unstable. The trigger is the single event that finally initiated the landslide. Thus, causes combine to make a slope vulnerable to failure, and the trigger finally initiates the movement. Landslides can have many causes but can only have one trigger. Usually, it is relatively easy to determine the trigger after the landslide has occurred (although it is generally very difficult to determine the exact nature of landslide triggers ahead of a movement event).

Classification factors

Various scientific disciplines have developed taxonomic classification systems to describe natural phenomena or individuals, like for example, plants or animals. These systems are based on specific characteristics like shape of organs or nature of reproduction. Differently, in landslide classification, there are great difficulties because phenomena are not perfectly repeatable; usually being characterised by different causes, movements and morphology, and involving genetically different material. For this reason, landslide classifications are based on different discriminating factors, sometimes very subjective. In the following write-up, factors are discussed by dividing them into two groups: the first one is made up of the criteria utilised in the most widespread classification systems that can generally be easily determined. The second one is formed by those factors that have been utilised in some classifications and can be useful in descriptions.

A1) Type of movement

This is the most important criterion, even if uncertainties and difficulties can arise in the identification of movements, being the mechanisms of some landslides often particularly complex. The main movements are falls, slides and flows, but usually topples, lateral spreading and complex movements are added to these.

A2) Involved material

Rock, earth and debris are the terms generally used to distinguish the materials involved in the landslide process. For example, the distinction between earth and debris is usually made by comparing the percentage of coarse grain size fractions. If the weight of the particles with a diameter greater than 2 mm is less than 20%, the material will be defined as earth; in the opposite case, it is debris.

A3) Activity

The classification of a landslide based on its activity is particularly relevant in the evaluation of future events. The recommendations of the WP/WLI (1993) define the concept of activity with reference to the spatial and temporal conditions, defining the state, the distribution and the style. The first term describes the information regarding the time in which the movement took place, permitting information to be available on future evolution, the second term describes, in a general way, where the landslide is moving and the third term indicates how it is moving.

A4) Movement velocity

This factor has a great importance in the hazard evaluation. A velocity range is connected to the different type of landslides, on the basis of observation of case history or site observations.

B1) The age of the movement

Landslide dating is an interesting topic in the evaluation of hazard. The knowledge of the landslide frequency is a fundamental element for any kind of probabilistic evaluation. Furthermore, the evaluation of the age of the landslide permits to correlate the trigger to specific conditions, as earthquakes or periods of intense rains. It is possible that phenomena could be occurred in past geological times, under specific environmental conditions which no longer act as agents today. For example, in some Alpine areas, landslides of the Pleistocene age are connected with particular tectonic, geomorphological and climatic conditions.

B2) Geological conditions

This represent a fundamental factor of the morphological evolution of a slope. Bedding attitude and the presence of discontinuities or faults control the slope morphogenesis.

B3) Morphological characteristics

As the landslide is a geological volume with a hidden side, morphological characteristics are extremely important in the reconstruction of the technical model.

B4) Geographical location

This criterion describes, in a general way, the location of landslides in the physiographic context of the area. Some authors have therefore identified landslides according to their geographical position so that it is possible to describe "alpine landslides", "landslides in plains", "hilly landslides" or "cliff landslides". As a consequence, specific morphological contexts are referred characterised by slope evolution processes.

B5) Topographical criteria

With these criteria, landslides can be identified with a system similar to that of the denomination of formations. Consequently, it is possible to describe a landslide using the name of a site. In particular, the name will be that of the locality where the landslide happened with a specific characteristic type.

B6) Type of climate

These criteria give particular importance to climate in the genesis of phenomena for which similar geological conditions can, in different climatic conditions, lead to totally different morphological evolution. As a consequence, in the description of a landslide, it can be interesting to understand in what type of climate the event occurred.

B7) Causes of the movements

In the evaluation of landslide susceptibility, causes of the triggers is an important step. Terzaghi describes causes as "internal" and "external" referring to modifications in the conditions of the stability of the bodies. Whilst the internal causes induce modifications in the material itself which decrease its resistance to shear stress, the external causes generally induce an increase of shear stress, so that block or bodies are no longer stable. The triggering causes induce the movement of the mass. Predisposition to movement due to control factors is determining in landslide evolution. Structural and geological factors, as already described, can determine the development of the movement, inducing the presence of mass in kinematic freedom.

Types and classification

In traditional usage, the term landslide has at one time or another been used to cover almost all forms of mass movement of rocks and regolith at the Earth's surface. In 1978, in a very highly cited publication, David Varnes noted this imprecise usage and proposed a new, much tighter scheme for the classification of mass movements and subsidence processes.[1] This scheme was later modified by Cruden and Varnes in 1996,[3] and influentially refined by Hutchinson (1988)[4] and Hungr et al. (2001).[2] This full scheme results in the following classification for mass movements in general, where bold font indicates the landslide categories:

| Type of movement | Type of material | ||||

| Bedrock | Engineering soils | ||||

| Predominantly fine | Predominantly coarse | ||||

| Falls | Rockfall | Earth fall | Debris fall | ||

| Topples | Rock topple | Earth topple | Debris topple | ||

| Slides | Rotational | Rock slump | Earth slump | Debris slump | |

| Translational | Few units | Rock block slide | Earth block slide | Debris block slide | |

| Many units | Rock slide | Earth slide | Debris slide | ||

| Lateral spreads | Rock spread | Earth spread | Debris spread | ||

| Flows | Rock flow | Earth flow | Debris flow | ||

| Rock avalanche | Debris avalanche | ||||

| (Deep creep) | (Soil creep) | ||||

| Complex and compound | Combination in time and/or space of two or more principal types of movement | ||||

Under this definition, landslides are restricted to "the movement... of shear strain and displacement along one or several surfaces that are visible or may reasonably be inferred, or within a relatively narrow zone",[1] i.e., the movement is localised to a single failure plane within the subsurface. He noted landslides can occur catastrophically, or that movement on the surface can be gradual and progressive. Falls (isolated blocks in free-fall), topples (material coming away by rotation from a vertical face), spreads (a form of subsidence), flows (fluidised material in motion), and creep (slow, distributed movement in the subsurface) are all explicitly excluded from the term landslide.

Under the scheme, landslides are sub-classified by the material that moves, and by the form of the plane or planes on which movement happens. The planes may be broadly parallel to the surface ("translational slides") or spoon-shaped ("rotational slides"). Material may be rock or regolith (loose material at the surface), with regolith subdivided into debris (coarse grains) and earth (fine grains).

Nevertheless, in broader usage, many of the categories that Varnes excluded are recognised as landslide types, as seen below. This leads to ambiguity in usage of the term.

The following clarifies the usages of the various terms in the table. Varnes and those who later modified his scheme only regard the slides category as forms of landslide.

Falls

Description: " the detachment of soil or rock from a steep slope along a surface on which little or no shear displacement takes place. The material then descends mainly through the air by falling, bouncing, or rolling" (Varnes, 1996).

Secondary falls: "Secondary falls involves rock bodies already physically detached from cliff and merely lodged upon it" (Hutchinson, 1988)

Speed: from very to extremely rapid

Type of slope: slope angle 45–90 degrees

Control factor: Discontinuities

Causes: Vibration, undercutting, differential weathering, excavation, or stream erosion

Topples

Description: "Toppling is the forward rotation out of the slope of a mass of soil or rock about a point or axis below the centre of gravity of the displaced mass. Toppling is sometimes driven by gravity exerted by material upslope of the displaced mass and sometimes by water or ice in cracks in the mass" (Varnes, 1996)

Speed: extremely slow to extremely rapid

Type of slope: slope angle 45–90 degrees

Control factor: Discontinuities, lithostratigraphy

Causes: Vibration, undercutting, differential weathering, excavation, or stream erosion

Slides

"A slide is a downslope movement of soil or rock mass occurring dominantly on the surface of rupture or on relatively thin zones of intense shear strain." (Varnes, 1996)

Translational slide

Description: "In translational slides the mass displaces along a planar or undulating surface of rupture, sliding out over the original ground surface." (Varnes, 1996)

Speed: extremely slow to extremely rapid (>5 m/s)

Type of slope: slope angle 20-45 degrees

Control factor: Discontinuities, geological setting

Rotational slides

Description: "Rotational slides move along a surface of rupture that is curved and concave" (Varnes, 1996)

Speed: extremely slow to extremely rapid

Type of slope: slope angle 20–40 degrees[5]

Control factor: morphology and lithology

Causes: Vibration, undercutting, differential weathering, excavation, or stream erosion

Spreads

"Spread is defined as an extension of a cohesive soil or rock mass combined with a general subsidence of the fractured mass of cohesive material into softer underlying material." (Varnes, 1996). "In spread, the dominant mode of movement is lateral extension accommodated by shear or tensile fractures" (Varnes, 1978)

Speed: extremely slow to extremely rapid (>5 m/s)

Type of slope: angle 45–90 degrees

Control factor: Discontinuities, lithostratigraphy

Causes: Vibration, undercutting, differential weathering, excavation, or stream erosion

Flows

A flow is a spatially continuous movement in which surfaces of shear are short-lived, closely spaced, and usually not preserved. The distribution of velocities in the displacing mass resembles that in a viscous liquid. The lower boundary of displaced mass may be a surface along which appreciable differential movement has taken place or a thick zone of distributed shear (Cruden & Varnes, 1996)

Flows in rock

Rock Flow

Description: "Flow movements in bedrock include deformations that are distributed among many large or small fractures, or even microfracture, without concentration of displacement along a through-going fracture" (Varnes, 1978)

Speed: extremely slow

Type of slope: angle 45–90 degrees

Causes: Vibration, undercutting, differential weathering, excavation, or stream erosion

Rock avalanche (Sturzstrom)

Description: "Extremely rapid, massive, flow-like motion of fragmented rock from a large rock slide or rock fall" (Hungr, 2001)

Speed: extremely rapid

Type of slope: angle 45–90 degrees

Control factor: Discontinuities, lithostratigraphy

Causes: Vibration, undercutting, differential weathering, excavation or stream erosion

Flows in soil

Debris flow

Description: "Debris flow is a very rapid to extremely rapid flow of saturated non-plastic debris in a steep channel" (Hungr et al.,2001)

Speed: very rapid to extremely rapid (>5 m/s)

Type of slope: angle 20–45 degrees

Control factor: torrent sediments, water flows

Causes: High intensity rainfall

Debris avalanche

Description: "Debris avalanche is a very rapid to extremely rapid shallow flow of partially or fully saturated debris on a steep slope, without confinement in an established channel." (Hungr et al., 2001)

Speed: very rapid to extremely rapid (>5 m/s)

Type of slope: angle 20–45 degrees

Control factor: morphology, regolith

Causes: High intensity rainfalls

Earth flow

Description: "Earth flow is a rapid or slower, intermittent flow-like movement of plastic, clayey earth." (Hungr et al.,2001)

Speed: slow to rapid (>1.8 m/h)

Type of slope: slope angle 5–25 degrees

Control factor: lithology

Mudflow

Description: "Mudflow is a very rapid to extremely rapid flow of saturated plastic debris in a channel, involving significantly greater water content relative to the source material (Plasticity index> 5%)." (Hungr et al.,2001)

Speed: very rapid to extremely rapid (>5 m/s)

Type of slope: angle 20–45 degrees

Control factor: torrent sediments, water flows

Causes: High intensity rainfall

Complex movement

Description: Complex movement is a combination of falls, topples, slides, spreads and flows

File:Global Rainfall-Triggered Landslides from 2007 through 2015.webm

Causes

Landslide causes include geological factors, morphological factors, physical factors and factors associated with human activity.

Geological causes

- Weathered materials

- Sheared materials

- Jointed or fissured materials

- Adversely orientated discontinuities

- Permeability contrasts

- Material contrasts

- Rainfall and snow fall

- Earthquakes

Morphological causes

- Slope angle

- Uplift

- Rebound

- Fluvial erosion

- Wave erosion

- Glacial erosion

- Erosion of lateral margins

- Subterranean erosion

- Internal erosion[6]

- Slope loading

- Vegetation change

- Erosion

Physical causes

Topography:

- Slope aspect and gradient

Geological factors:

- Discontinuity factors (dip spacing, asperity, dip and length)

- Physical characteristics of the rock (rock strength etc.)

Tectonic activity:

- Seismic activity (earthquakes)

- Volcanic eruption

Physical weathering:

- Thawing

- Freeze-thaw

- Soil erosion

Hydrogeological factors:

- Intense rainfall

- Rapid snow melt

- Prolonged precipitation

- Ground water changes (rapid drawdown)

- Soil pore water pressure

- Surface runoff

Human causes

- Deforestation

- Excavation

- Loading

- Water management (groundwater drawdown and water leakage)

- Land use (e.g. construction of roads, houses etc.)

- Mining and quarrying

- Vibration

Occasionally, even after detailed investigations, no trigger can be determined - this was the case in the large Aoraki / Mount Cook landslide in New Zealand 1991. It is unclear as to whether the lack of a trigger in such cases is the result of some unknown process acting within the landslide, or whether there was in fact a trigger, but it cannot be determined. The trigger may be due to a slow but steady decrease in material strength associated with the weathering of the rock - at some point the material becomes so weak that failure must occur. Hence, the trigger is the weathering process, but this is not detectable externally. In most cases a trigger is thought as an external stimulus that induces an immediate or near-immediate response in the slope, in this case in the form of the movement of the landslide. Generally, this movement is induced either because the stresses in the slope are altered by increasing shear stress or decreasing the effective normal stress, or by reducing the resistance to the movement perhaps by decreasing the shear strength of the materials within the landslide.

Rainfall

In the majority of cases the main trigger of landslides is heavy or prolonged rainfall. Generally this takes the form of either an exceptional short lived event, such as the passage of a tropical cyclone or even the rainfall associated with a particularly intense thunderstorm or of a long duration rainfall event with lower intensity, such as the cumulative effect of monsoon rainfall in South Asia. In the former case it is usually necessary to have very high rainfall intensities, whereas in the latter the intensity of rainfall may be only moderate - it is the duration and existing pore water pressure conditions that are important.

The importance of rainfall as a trigger for landslides cannot be overestimated. A global survey of landslide occurrence in the 12 months to the end of September 2003 revealed that there were 210 damaging landslide events worldwide. Of these, over 90% were triggered by heavy rainfall. One rainfall event for example in Sri Lanka in May 2003 triggered hundreds of landslides, killing 266 people and rendering over 300,000 people temporarily homeless. In July 2003 an intense rain band associated with the annual Asian monsoon tracked across central Nepal, triggering 14 fatal landslides that killed 85 people. The reinsurance company Swiss Re estimated that rainfall induced landslides associated with the 1997-1998 El Nino event triggered landslides along the west coast of North, Central and South America that resulted in over $5 billion in losses. Finally, landslides triggered by Hurricane Mitch in 1998 killed an estimated 18,000 people in Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala and El Salvador.

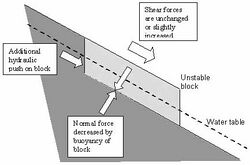

Rainfall triggers a large amount of landslides principally because the rainfall drives an increase in pore water pressure within the soil. Figure A illustrates the forces acting on an unstable block on a slope. Movement is driven by shear stress, which is generated by the mass of the block acting under gravity down the slope. Resistance to movement is the result of the normal load. When the slope fills with water, the fluid pressure provides the block with buoyancy, reducing the resistance to movement. In addition, in some cases fluid pressures can act down the slope as a result of groundwater flow to provide a hydraulic push to the landslide that further decreases the stability. Whilst the example given in Figures A and B is clearly an artificial situation, the mechanics are essentially as per a real landslide.

In some situations, the presence of high levels of fluid may destabilise the slope through other mechanisms, such as:

- Fluidization of debris from earlier events to form debris flows;

- Loss of suction forces in silty materials, leading to generally shallow failures (this may be an important mechanism in residual soils in tropical areas following deforestation);

- Undercutting of the toe of the slope through river erosion.

- Destabilizing of non-lithified earth materials through soil-piping.[7]

Considerable efforts have been made to understand the triggers for landsliding in natural systems, with quite variable results. For example, working in Puerto Rico, Larsen and Simon found that storms with a total precipitation of 100–200 mm, about 14 mm of rain per hour for several hours, or 2–3 mm of rain per hour for about 100 hours can trigger landslides in that environment. Rafi Ahmad, working in Jamaica, found that for rainfall of short duration (about 1 hour) intensities of greater than 36 mm/h were required to trigger landslides. On the other hand, for long rainfall durations, low average intensities of about 3 mm/h appeared to be sufficient to cause landsliding as the storm duration approached approximately 100 hours.

Corominas and Moya (1999) found that the following thresholds exist for the upper basin of the Llobregat River, Eastern Pyrenees area. Without antecedent rainfall, high intensity and short duration rains triggered debris flows and shallow slides developed in colluvium and weathered rocks. A rainfall threshold of around 190 mm in 24 h initiated failures whereas more than 300 mm in 24-48 h were needed to cause widespread shallow landsliding. With antecedent rain, moderate intensity precipitation of at least 40 mm in 24 h reactivated mudslides and both rotational and translational slides affecting clayey and silty-clayey formations. In this case, several weeks and 200 mm of precipitation were needed to cause landslide reactivation. A similar approach is reported by Brand et al. (1988) for Hong Kong, who found that if the 24-hour antecedent rainfall exceeded 200 mm then the rainfall threshold for a large landslide event was 70 mm·h−1. Finally, Caine (1980) established a worldwide threshold:

I = 14.82 D - 0.39 where: I is the rainfall intensity (mm·h−1), D is duration of rainfall (h)

This threshold applies over time periods of 10 minutes to 10 days. It is possible to modify the formula to take into consideration areas with high mean annual precipitations by considering the proportion of mean annual precipitation represented by any individual event. Other techniques can be used to try to understand rainfall triggers, including:

• Actual rainfall techniques, in which measurements of rainfall are adjusted for potential evapotranspiration and then correlated with landslide movement events

• Hydrogeological balance approaches, in which pore water pressure response to rainfall is used to understand the conditions under which failures are initiated

• Coupled rainfall - stability analysis methods, in which pore water pressure response models are coupled to slope stability models to try to understand the complexity of the system

• Numerical slope modelling, in which finite element (or similar) models are used to try to understand the interactions of all relevant processes

Seismicity

The second major factor in the triggering of landslides is seismicity. Landslides occur during earthquakes as a result of two separate but interconnected processes: seismic shaking and pore water pressure generation.

Seismic shaking

The passage of the earthquake waves through the rock and soil produces a complex set of accelerations that effectively act to change the gravitational load on the slope. So, for example, vertical accelerations successively increase and decrease the normal load acting on the slope. Similarly, horizontal accelerations induce a shearing force due to the inertia of the landslide mass during the accelerations. These processes are complex, but can be sufficient to induce failure of the slope. These processes can be much more serious in mountainous areas in which the seismic waves interact with the terrain to produce increases in the magnitude of the ground accelerations. This process is termed 'topographic amplification'. The maximum acceleration is usually seen at the crest of the slope or along the ridge line, meaning that it is a characteristic of seismically triggered landslides that they extend to the top of the slope.

Liquefaction

The passage of the earthquake waves through a granular material such as a soil can induce a process termed liquefaction, in which the shaking causes a reduction in the pore space of the material. This densification drives up the pore pressure in the material. In some cases this can change a granular material into what is effectively a liquid, generating 'flow slides' that can be rapid and thus very damaging. Alternatively, the increase in pore pressure can reduce the normal stress in the slope, allowing the activation of translational and rotational failures.

The nature of seismically-triggered landslides

For the main part seismically generated landslides usually do not differ in their morphology and internal processes from those generated under non-seismic conditions. However, they tend to be more widespread and sudden. The most abundant types of earthquake-induced landslides are rock falls and slides of rock fragments that form on steep slopes. However, almost every other type of landslide is possible, including highly disaggregated and fast-moving falls; more coherent and slower-moving slumps, block slides, and earth slides; and lateral spreads and flows that involve partly to completely liquefied material (Keefer, 1999). Rock falls, disrupted rock slides, and disrupted slides of earth and debris are the most abundant types of earthquake-induced landslides, whereas earth flows, debris flows, and avalanches of rock, earth, or debris typically transport material the farthest. There is one type of landslide that is essential uniquely limited to earthquakes - liquefaction failure, which can cause fissuring or subsidence of the ground. Liquefaction involves the temporary loss of strength of sands and silts which behave as viscous fluids rather than as soils. This can have devastating effects during large earthquakes.

Volcanic activity

Some of the largest and most destructive landslides known have been associated with volcanoes. These can occur either in association with the eruption of the volcano itself, or as a result of mobilisation of the very weak deposits that are formed as a consequence of volcanic activity. Essentially, there are two main types of volcanic landslide: lahars and debris avalanches, the largest of which are sometimes termed sector collapses. An example of a lahar was seen at Mount St Helens during its catastrophic eruption on May 18, 1980. Failures on volcanic flanks themselves are also common. For example, a part of the side of Casita Volcano in Nicaragua collapsed on October 30, 1998, during the heavy precipitation associated with the passage of Hurricane Mitch. Debris from the initial small failure eroded older deposits from the volcano and incorporated additional water and wet sediment from along its path, increasing in volume about ninefold. The lahar killed more than 2,000 people as it swept over the towns of El Porvenir and Rolando Rodriguez at the base of the mountain. Debris avalanches commonly occur at the same time as an eruption, but occasionally they may be triggered by other factors such as a seismic shock or heavy rainfall. They are particularly common on strato volcanoes, which can be massively destructive due to their large size. The most famous debris avalanche occurred at Mount St Helens during the massive eruption in 1980. On May 18, 1980, at 8:32 a.m. local time, a magnitude 5.1 earthquake shook Mount St. Helens. The bulge and surrounding area slid away in a gigantic rockslide and debris avalanche, releasing pressure, and triggering a major pumice and ash eruption of the volcano. The debris avalanche had a volume of about 1 km3 (0.24 cu mi), traveled at 50 to 80 m/s (110 to 180 mph), and covered an area of 62 km2 (24 sq mi), killing 57 people.

Snowmelt

In many cold mountain areas, snowmelt can be a key mechanism by which landslide initiation can occur. This can be especially significant when sudden increases in temperature lead to rapid melting of the snow pack. This water can then infiltrate into the ground, which may have impermeable layers below the surface due to still-frozen soil or rock, leading to rapid increases in pore water pressure, and resultant landslide activity. This effect can be especially serious when the warmer weather is accompanied by precipitation, which both adds to the groundwater and accelerates the rate of thawing.

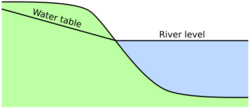

Water-level change

Rapid changes in the groundwater level along a slope can also trigger landslides. This is often the case where a slope is adjacent to a water body or a river. When the water level adjacent to the slope falls rapidly the groundwater level frequently cannot dissipate quickly enough, leaving an artificially high water table. This subjects the slope to higher than normal shear stresses, leading to potential instability. This is probably the most important mechanism by which river bank materials fail, being significant after a flood as the river level is declining (i.e. on the falling limb of the hydrograph) as shown in the following figures.

It can also be significant in coastal areas when sea level falls after a storm tide, or when the water level of a reservoir or even a natural lake rapidly falls. The most famous example of this is the Vajont failure, when a rapid decline in lake level contributed to the occurrence of a landslide that killed over 2000 people. Numerous huge landslides also occurred in the Three Gorges (TG) after the construction of the TG dam.[8][9]

Rivers

In some cases, failures are triggered as a result of undercutting of the slope by a river, especially during a flood. This undercutting serves both to increase the gradient of the slope, reducing stability, and to remove toe weighting, which also decreases stability. For example, in Nepal this process is often seen after a glacial lake outburst flood, when toe erosion occurs along the channel. Immediately after the passage of flood waves extensive landsliding often occurs. This instability can continue to occur for a long time afterwards, especially during subsequent periods of heavy rain and flood events.

Colluvium-filled bedrock hollows

Colluvium-filled bedrock hollows are the cause of many shallow earth landslides in steep mountainous terrain. They can form as a U- or V-shaped trough as local bedrock variations reveal areas in the bedrock which are more prone to weathering than other locations on the slope. As the weathered bedrock turns to soil, there is a greater elevation difference between the soil level and the hard bedrock. With the introduction of water and the thick soil, there is less cohesion and the soil flows out in a landslide. With every landslide more bedrock is scoured out and the hollow becomes deeper. After time, colluvium fills the hollow, and the sequence starts again.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Varnes D. J., Slope movement types and processes. In: Schuster R. L. & Krizek R. J. Ed., Landslides, analysis and control. Transportation Research Board Sp. Rep. No. 176, Nat. Acad. oi Sciences, pp. 11–33, 1978.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hungr O, Evans SG, Bovis M, and Hutchinson JN (2001) Review of the classification of landslides of the flow type. Environmental and Engineering Geoscience VII, 221-238.

- ↑ Cruden, David M., and David J. Varnes. "Landslides: investigation and mitigation. Chapter 3-Landslide types and processes." Transportation research board special report 247 (1996).

- ↑ Hutchinson, J. N. "General report: morphological and geotechnical parameters of landslides in relation to geology and hydrogeology." International symposium on landslides. 5. 1988.

- ↑ https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/1325/pdf/Sections/Section1.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ↑ Jacob, Jeemon (September 5, 2019). "Kerala's man-made disaster". https://www.indiatoday.in/india-today-insight/story/kerala-manmade-disaster-flood-1595657-2019-09-05. "soil-piping is a major cause for the landslides witnessed..."

- ↑ Jacob, Jeemon (September 5, 2019). "Kerala's man-made disaster". https://www.indiatoday.in/india-today-insight/story/kerala-manmade-disaster-flood-1595657-2019-09-05. "soil-piping is a major cause for the landslides witnessed..."

- ↑ Jian, Wenxing; Xu, Qiang; Yang, Hufeng; Wang, Fawu (2014-10-01). "Mechanism and failure process of Qianjiangping landslide in the Three Gorges Reservoir, China" (in en). Environmental Earth Sciences 72 (8): 2999–3013. doi:10.1007/s12665-014-3205-x. ISSN 1866-6280. Bibcode: 2014EES....72.2999J.

- ↑ Tomas, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, P.; Singleton, A.; Hoey, T.; Cheng, X. (2014-04-01). "Spatiotemporal characteristics of the Huangtupo landslide in the Three Gorges region (China) constrained by radar interferometry" (in en). Geophysical Journal International 197 (1): 213–232. doi:10.1093/gji/ggu017. ISSN 0956-540X.

Further reading

- Caine, N., 1980. The rainfall intensity-duration control of shallow landslides and debris flows. Geografiska Annaler, 62A, 23–27.

- Coates, D. R. (1977) - Landslide prospectives. In: Landslides (D.R. Coates, Ed.) Geological Society of America, pp. 3–38.

- Corominas, J. and Moya, J. 1999. Reconstructing recent landslide activity in relation to rainfall in the Llobregat River basin, Eastern Pyrenees, Spain. Geomorphology, 30, 79–93.

- Cruden D.M., VARNES D. J. (1996) - Landslide types and processes. In: Turner A.K.; Shuster R.L. (eds) Landslides: Investigation and Mitigation. Transp Res Board, Spec Rep 247, pp 36–75.

- Hungr O, Evans SG, Bovis M, and Hutchinson JN (2001) Review of the classification of landslides of the flow type. Environmental and Engineering Geoscience VII, 221–238.'

- Hutchinson J. N.: Mass Movement. In: The Encyclopedia of Geomorphology (Fairbridge, R.W., ed.), Reinhold Book Corp., New York, pp. 688–696, 1968.'

- Harpe C. F. S.: Landslides and related phenomena. A Study of Mass Movements of Soil and Rock. Columbia Univo Press, New York, 137 pp., 1938

- Keefer, D.K. (1984) Landslides caused by earthquakes. Bulletin of the Geological Society of America 95, 406-421

- Varnes D. J.: Slope movement types and processes. In: Schuster R. L. & Krizek R. J. Ed., Landslides, analysis and control. Transportation Research Board Sp. Rep. No. 176, Nat. Acad. oi Sciences, pp. 11–33, 1978.'

- Terzaghi K. - Mechanism of Landslides. In Engineering Geology (Berkel) Volume. Ed. da The Geological Society of America~ New York, 1950.

- WP/ WLI. 1993. A suggested method for describing the activity of a landslide. Bulletin of the International Association of Engineering Geology, No. 47, pp. 53–57

- Dunne, Thomas. Journal of the American Water Resources Association. August 1998, V. 34, NO. 4.

- www3.interscience.wiley.com JAWRA Journal of the American Water Resources AssociationVolume 34, Issue 4, Article first published online: 8 JUN 2007[|permanent dead link|dead link}}] (registration required)

- 2016, Ventura County Star. A driveway in Camarillo, California (466 E. Highland Ave., Camarillo, CA) sinks and a landslide ensues engulfing the driveway within minutes.

|

KSF

KSF