Polar amplification

Topic: Earth

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

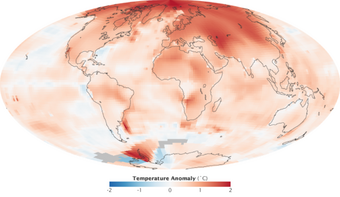

Polar amplification is the phenomenon that any change in the net radiation balance (for example greenhouse intensification) tends to produce a larger change in temperature near the poles than in the planetary average.[1] This is commonly referred to as the ratio of polar warming to tropical warming. On a planet with an atmosphere that can restrict emission of longwave radiation to space (a greenhouse effect), surface temperatures will be warmer than a simple planetary equilibrium temperature calculation would predict. Where the atmosphere or an extensive ocean is able to transport heat polewards, the poles will be warmer and equatorial regions cooler than their local net radiation balances would predict.[2] The poles will experience the most cooling when the global-mean temperature is lower relative to a reference climate; alternatively, the poles will experience the greatest warming when the global-mean temperature is higher.[1]

In the extreme, the planet Venus is thought to have experienced a very large increase in greenhouse effect over its lifetime,[3] so much so that its poles have warmed sufficiently to render its surface temperature effectively isothermal (no difference between poles and equator).[4][5] On Earth, water vapor and trace gasses provide a lesser greenhouse effect, and the atmosphere and extensive oceans provide efficient poleward heat transport. Both palaeoclimate changes and recent global warming changes have exhibited strong polar amplification, as described below.

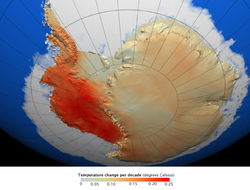

Arctic amplification is polar amplification of the Earth's North Pole only; Antarctic amplification is that of the South Pole.

History

An observation-based study related to Arctic amplification was published in 1969 by Mikhail Budyko,[6] and the study conclusion has been summarized as "Sea ice loss affects Arctic temperatures through the surface albedo feedback."[7][8] The same year, a similar model was published by William D. Sellers.[9] Both studies attracted significant attention since they hinted at the possibility for a runaway positive feedback within the global climate system.[10] In 1975, Manabe and Wetherald published the first somewhat plausible general circulation model that looked at the effects of an increase of greenhouse gas. Although confined to less than one-third of the globe, with a "swamp" ocean and only land surface at high latitudes, it showed an Arctic warming faster than the tropics (as have all subsequent models).[11]

Amplification

Amplifying mechanisms

Feedbacks associated with sea ice and snow cover are widely cited as one of the principal causes of terrestrial polar amplification.[12][13][14] These feedbacks are particularly noted in local polar amplification,[15] although recent work has shown that the lapse rate feedback is likely equally important to the ice-albedo feedback for Arctic amplification.[16] Supporting this idea, large-scale amplification is also observed in model worlds with no ice or snow.[17] It appears to arise both from a (possibly transient) intensification of poleward heat transport and more directly from changes in the local net radiation balance.[17] Local radiation balance is crucial because an overall decrease in outgoing longwave radiation will produce a larger relative increase in net radiation near the poles than near the equator.[16] Thus, between the lapse rate feedback and changes in the local radiation balance, much of polar amplification can be attributed to changes in outgoing longwave radiation.[15][18] This is especially true for the Arctic, whereas the elevated terrain in Antarctica limits the influence of the lapse rate feedback.[16][19]

Some examples of climate system feedbacks thought to contribute to recent polar amplification include the reduction of snow cover and sea ice, changes in atmospheric and ocean circulation, the presence of anthropogenic soot in the Arctic environment, and increases in cloud cover and water vapor.[13] CO2 forcing has also been attributed to polar amplification.[20] Most studies connect sea ice changes to polar amplification.[13] Both ice extent and thickness impact polar amplification. Climate models with smaller baseline sea ice extent and thinner sea ice coverage exhibit stronger polar amplification.[21] Some models of modern climate exhibit Arctic amplification without changes in snow and ice cover.[22]

The individual processes contributing to polar warming are critical to understanding climate sensitivity.[23] Polar warming also affects many ecosystems, including marine and terrestrial ecosystems, climate systems, and human populations.[20] Polar amplification is largely driven by local polar processes with hardly any remote forcing, whereas polar warming is regulated by tropical and midlatitude forcing.[24] These impacts of polar amplification have led to continuous research in the face of global warming.

Ocean circulation

It has been estimated that 70% of global wind energy is transferred to the ocean and takes place within the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC).[25] Eventually, upwelling due to wind-stress transports cold Antarctic waters through the Atlantic surface current, while warming them over the equator, and into the Arctic environment. This is especially noticed in high latitudes.[21] Thus, warming in the Arctic depends on the efficiency of the global ocean transport and plays a role in the polar see-saw effect.[25]

Decreased oxygen and low-pH during La Niña are processes that correlate with decreased primary production and a more pronounced poleward flow of ocean currents.[26] It has been proposed that the mechanism of increased Arctic surface air temperature anomalies during La Niña periods of ENSO may be attributed to the Tropically Excited Arctic Warming Mechanism (TEAM), when Rossby waves propagate more poleward, leading to wave dynamics and an increase in downward infrared radiation.[1][27]

Amplification factor

Polar amplification is quantified in terms of a polar amplification factor, generally defined as the ratio of some change in a polar temperature to a corresponding change in a broader average temperature:

- ,

where is a change in polar temperature and is, for example, a corresponding change in a global mean temperature.

Common implementations[28][29] define the temperature changes directly as the anomalies in surface air temperature relative to a recent reference interval (typically 30 years). Others have used the ratio of the variances of surface air temperature over an extended interval.[30]

Amplification phase

It is observed that Arctic and Antarctic warming commonly proceed out of phase because of orbital forcing, resulting in the so-called polar see-saw effect.[31]

Paleoclimate polar amplification

The glacial / interglacial cycles of the Pleistocene provide extensive palaeoclimate evidence of polar amplification, both from the Arctic and the Antarctic.[29] In particular, the temperature rise since the last glacial maximum 20,000 years ago provides a clear picture. Proxy temperature records from the Arctic (Greenland) and from the Antarctic indicate polar amplification factors on the order of 2.0.[29]

Recent Arctic amplification

Suggested mechanisms leading to the observed Arctic amplification include Arctic sea ice decline (open water reflects less sunlight than sea ice), atmospheric heat transport from the equator to the Arctic,[33] and the lapse rate feedback.[16]

The Arctic was historically described as warming twice as fast as the global average,[34] but this estimate was based on older observations which missed the more recent acceleration. By 2021, enough data was available to show that the Arctic had warmed three times as fast as the globe - 3.1 °C between 1971 and 2019, as opposed to the global warming of 1 °C over the same period.[35] Moreover, this estimate defines the Arctic as everything above 60th parallel north, or a full third of the Northern Hemisphere: in 2021–2022, it was found that since 1979, the warming within the Arctic Circle itself (above the 66th parallel) has been nearly four times faster than the global average.[36][37] Within the Arctic Circle itself, even greater Arctic amplification occurs in the Barents Sea area, with hotspots around West Spitsbergen Current: weather stations located on its path record decadal warming up to seven times faster than the global average.[38][39] This has fuelled concerns that unlike the rest of the Arctic sea ice, ice cover in the Barents Sea may permanently disappear even around 1.5 degrees of global warming.[40][41]

The acceleration of Arctic amplification has not been linear: a 2022 analysis found that it occurred in two sharp steps, with the former around 1986, and the latter after 2000.[42] The first acceleration is attributed to the increase in anthropogenic radiative forcing in the region, which is in turn likely connected to the reductions in stratospheric sulfur aerosols pollution in Europe in the 1980s in order to combat acid rain. Since sulphate aerosols have a cooling effect, their absence is likely to have increased Arctic temperatures by up to 0.5 degrees Celsius.[43][44] The second acceleration has no known cause,[35] which is why it did not show up in any climate models. It is likely to be an example of multi-decadal natural variability, like the suggested link between Arctic temperatures and Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO),[45] in which case it can be expected to reverse in the future. However, even the first increase in Arctic amplification was only accurately simulated by a fraction of the current CMIP6 models.[42]

Possible impacts on mid-latitude weather

See also

- Arctic dipole anomaly

- Arctic oscillation

- Climate of the Arctic

- Polar vortex

- Sudden stratospheric warming

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Lee, Sukyoung (January 2014). "A theory for polar amplification from a general circulation perspective". Asia-Pacific Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 50 (1): 31–43. doi:10.1007/s13143-014-0024-7. Bibcode: 2014APJAS..50...31L. http://www.meteo.psu.edu/~sxl31/papers/APJAS_special_revision.pdf.

- ↑ Pierrehumbert, R. T. (2010). Principles of Planetary Climate. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86556-2.

- ↑ Kasting, J. F. (1988). "Runaway and moist greenhouse atmospheres and the evolution of Earth and Venus". Icarus 74 (3): 472–94. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(88)90116-9. PMID 11538226. Bibcode: 1988Icar...74..472K. https://zenodo.org/record/1253896.

- ↑ Williams, David R. (15 April 2005). "Venus Fact Sheet". NASA. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/venusfact.html.

- ↑ "Titan, Mars and Earth: Entropy Production by Latitudinal Heat Transport". Ames Research Center, University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. 2001. http://sirius.bu.edu/withers/pppp/pdf/mepgrl2001.pdf.

- ↑ Budyko, M.I. (1969). "The effect of solar radiation variations on the climate of the Earth". Tellus 21 (5): 611–9. doi:10.3402/tellusa.v21i5.10109. Bibcode: 1969Tell...21..611B.

- ↑ Cvijanovic, Ivana; Caldeira, Ken (2015). "Atmospheric impacts of sea ice decline in CO2 induced global warming". Climate Dynamics 44 (5–6): 1173–86. doi:10.1007/s00382-015-2489-1. Bibcode: 2015ClDy...44.1173C. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs00382-015-2489-1.pdf.

- ↑ "Ice in Action: Sea ice at the North Pole has something to say about climate change". YaleScientific. 2016. http://www.yalescientific.org/2016/06/ice-in-action-sea-ice-at-the-north-pole-has-something-to-say-about-climate-change.

- ↑ Sellers, William D. (1969). "A Global Climatic Model Based on the Energy Balance of the Earth-Atmosphere System". Journal of Applied Meteorology 8 (3): 392–400. doi:10.1175/1520-0450(1969)008<0392:AGCMBO>2.0.CO;2. Bibcode: 1969JApMe...8..392S.

- ↑ Oldfield, Jonathan D. (2016). "Mikhail Budyko's (1920–2001) contributions to Global Climate Science: from heat balances to climate change and global ecology". Advanced Review 7 (5): 682–692. doi:10.1002/wcc.412.

- ↑ Manabe, Syukoro; Wetherald, Richard T. (1975). "The Effects of Doubling the CO2 Concentration on the Climate of a General Circulation Model". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences 32 (1): 3–15. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1975)032<0003:TEODTC>2.0.CO;2. Bibcode: 1975JAtS...32....3M.

- ↑ "Radiative forcing and climate response". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 102 (D6): 6831–64. 1997. doi:10.1029/96jd03436. Bibcode: 1997JGR...102.6831H.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "IPCC AR5 – Near-term Climate Change: Projections and Predictability (Chapter 11 / page 983 )". 2013. http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/report/WG1AR5_Chapter11_FINAL.pdf.

- ↑ Pistone, Kristina; Eisenman, Ian; Ramanathan, Veerabhadran (2019). "Radiative Heating of an Ice-Free Arctic Ocean" (in en). Geophysical Research Letters 46 (13): 7474–7480. doi:10.1029/2019GL082914. Bibcode: 2019GeoRL..46.7474P. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/678849wc.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Bekryaev, Roman V.; Polyakov, Igor V.; Alexeev, Vladimir A. (2010-07-15). "Role of Polar Amplification in Long-Term Surface Air Temperature Variations and Modern Arctic Warming" (in EN). Journal of Climate 23 (14): 3888–3906. doi:10.1175/2010JCLI3297.1. ISSN 0894-8755. Bibcode: 2010JCli...23.3888B.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Goosse, Hugues; Kay, Jennifer E.; Armour, Kyle C.; Bodas-Salcedo, Alejandro; Chepfer, Helene; Docquier, David; Jonko, Alexandra; Kushner, Paul J. et al. (December 2018). "Quantifying climate feedbacks in polar regions". Nature Communications 9 (1): 1919. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04173-0. PMID 29765038. Bibcode: 2018NatCo...9.1919G.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Polar amplification of surface warming on an aquaplanet in "ghost forcing" experiments without sea ice feedbacks". Climate Dynamics 24 (7–8): 655–666. 2005. doi:10.1007/s00382-005-0018-3. Bibcode: 2005ClDy...24..655A.

- ↑ Payne, Ashley E.; Jansen, Malte F.; Cronin, Timothy W. (2015). "Conceptual model analysis of the influence of temperature feedbacks on polar amplification" (in en). Geophysical Research Letters 42 (21): 9561–9570. doi:10.1002/2015GL065889. ISSN 1944-8007. Bibcode: 2015GeoRL..42.9561P.

- ↑ Hahn, L. C.; Armour, K. C.; Battisti, D. S.; Donohoe, A.; Pauling, A. G.; Bitz, C. M. (28 August 2020). "Antarctic Elevation Drives Hemispheric Asymmetry in Polar Lapse Rate Climatology and Feedback". Geophysical Research Letters 47 (16). doi:10.1029/2020GL088965. Bibcode: 2020GeoRL..4788965H. http://eartharxiv.org/6fbjk/.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Stuecker, Malte F.; Bitz, Cecilia M.; Armour, Kyle C.; Proistosescu, Cristian; Kang, Sarah M.; Xie, Shang Ping; Kim, Doyeon; McGregor, Shayne et al. (December 2018). "Polar amplification dominated by local forcing and feedbacks" (in en). Nature Climate Change 8 (12): 1076–1081. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0339-y. ISSN 1758-6798. Bibcode: 2018NatCC...8.1076S. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-018-0339-y.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Holland, M. M.; Bitz, C. M. (2003-09-01). "Polar amplification of climate change in coupled models" (in en). Climate Dynamics 21 (3): 221–232. doi:10.1007/s00382-003-0332-6. ISSN 1432-0894. Bibcode: 2003ClDy...21..221H.

- ↑ Pithan, Felix; Mauritsen, Thorsten (February 2, 2014). "Arctic amplification dominated by temperature feedbacks in contemporary climate models". Nature Geoscience 7 (3): 181–4. doi:10.1038/ngeo2071. Bibcode: 2014NatGe...7..181P.

- ↑ Taylor, Patrick C.; Cai, Ming; Hu, Aixue; Meehl, Jerry; Washington, Warren; Zhang, Guang J. (2013-09-09). "A Decomposition of Feedback Contributions to Polar Warming Amplification". Journal of Climate (American Meteorological Society) 26 (18): 7023–7043. doi:10.1175/jcli-d-12-00696.1. ISSN 0894-8755. Bibcode: 2013JCli...26.7023T.

- ↑ Stuecker, Malte F.; Bitz, Cecilia M.; Armour, Kyle C.; Proistosescu, Cristian; Kang, Sarah M.; Xie, Shang-Ping; Kim, Doyeon; McGregor, Shayne et al. (December 2018). "Polar amplification dominated by local forcing and feedbacks" (in en). Nature Climate Change 8 (12): 1076–1081. doi:10.1038/s41558-018-0339-y. ISSN 1758-6798. Bibcode: 2018NatCC...8.1076S. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41558-018-0339-y.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Petr Chylek; Chris K. Folland; Glen Lesins; Manvendra K. Dubey (February 3, 2010). "Twentieth century bipolar seesaw of the Arctic and Antarctic surface air temperatures". Geophysical Research Letters 12 (8): 4015–22. doi:10.1029/2010GL042793. Bibcode: 2010GeoRL..37.8703C. http://www.leif.org/EOS/2010GL042793.pdf. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ↑ Sung Hyun Nam; Hey-Jin Kim; Uwe Send (November 23, 2011). "Amplification of hypoxic and acidic events by La Niña conditions on the continental shelf off California". Geophysical Research Letters 83 (22): L22602. doi:10.1029/2011GL049549. Bibcode: 2011GeoRL..3822602N.

- ↑ Sukyoung Lee (June 2012). "Testing of the Tropically Excited Arctic Warming Mechanism (TEAM) with Traditional El Niño and La Niña". Journal of Climate 25 (12): 4015–22. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00055.1. Bibcode: 2012JCli...25.4015L.

- ↑ Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. (2006). "Past and future polar amplification of climate change: climate model intercomparisons and ice-core constraints". Climate Dynamics 26 (5): 513–529. doi:10.1007/s00382-005-0081-9. Bibcode: 2006ClDy...26..513M.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 James Hansen; Makiko Sato; Gary Russell; Pushker Kharecha (September 2013). "Climate sensitivity, sea level and atmospheric carbon dioxide". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 371 (2001). doi:10.1098/rsta.2012.0294. PMID 24043864. Bibcode: 2013RSPTA.37120294H.

- ↑ Kobashi, T.; Shindell, D. T.; Kodera, K.; Box, J. E.; Nakaegawa, T.; Kawamura, K. (2013). "On the origin of multidecadal to centennial Greenland temperature anomalies over the past 800 yr". Climate of the Past 9 (2): 583–596. doi:10.5194/cp-9-583-2013. Bibcode: 2013CliPa...9..583K.

- ↑ Kyoung-nam Jo; Kyung Sik Woo; Sangheon Yi; Dong Yoon Yang; Hyoun Soo Lim; Yongjin Wang; Hai Cheng; R. Lawrence Edwards (March 30, 2014). "Mid-latitude interhemispheric hydrologic seesaw over the past 550,000 years". Nature 508 (7496): 378–382. doi:10.1038/nature13076. PMID 24695222. Bibcode: 2014Natur.508..378J.

- ↑ "Thermodynamics: Albedo". NSIDC. https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/seaice/processes/albedo.html.

- ↑ "Arctic amplification". NASA. 2013. https://climate.nasa.gov/news/927/arctic-amplification.

- ↑ "Polar Vortex: How the Jet Stream and Climate Change Bring on Cold Snaps" (in en). InsideClimate News. 2018-02-02. https://insideclimatenews.org/news/02022018/cold-weather-polar-vortex-jet-stream-explained-global-warming-arctic-ice-climate-change.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Arctic warming three times faster than the planet, report warns" (in en). 2021-05-20. https://phys.org/news/2021-05-arctic-faster-planet.html.

- ↑ Rantanen, Mika; Karpechko, Alexey Yu; Lipponen, Antti; Nordling, Kalle; Hyvärinen, Otto; Ruosteenoja, Kimmo; Vihma, Timo; Laaksonen, Ari (11 August 2022). "The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979" (in en). Communications Earth & Environment 3 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3. ISSN 2662-4435.

- ↑ "The Arctic is warming four times faster than the rest of the world" (in en). 2021-12-14. https://www.science.org/content/article/arctic-warming-four-times-faster-rest-world.

- ↑ Isaksen, Ketil et al. (15 June 2022). "Exceptional warming over the Barents area" (in en). Scientific Reports 12 (1): 9371. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-13568-5. PMID 35705593.

- ↑ Damian Carrington (2022-06-15). "New data reveals extraordinary global heating in the Arctic" (in en). https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jun/15/new-data-reveals-extraordinary-global-heating-in-the-arctic.

- ↑ Armstrong McKay, David; Abrams, Jesse; Winkelmann, Ricarda; Sakschewski, Boris; Loriani, Sina; Fetzer, Ingo; Cornell, Sarah; Rockström, Johan et al. (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points" (in en). Science 377 (6611): eabn7950. doi:10.1126/science.abn7950. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 36074831. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abn7950.

- ↑ Armstrong McKay, David (9 September 2022). "Exceeding 1.5°C global warming could trigger multiple climate tipping points – paper explainer" (in en). https://climatetippingpoints.info/2022/09/09/climate-tipping-points-reassessment-explainer/.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Chylek, Petr; Folland, Chris; Klett, James D.; Wang, Muyin; Hengartner, Nick; Lesins, Glen; Dubey, Manvendra K. (25 June 2022). "Annual Mean Arctic Amplification 1970–2020: Observed and Simulated by CMIP6 Climate Models" (in en). Geophysical Research Letters 49 (13). doi:10.1029/2022GL099371. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2022GL099371.

- ↑ Acosta Navarro, J.C.; Varma, V.; Riipinen, I.; Seland, Ø.; Kirkevåg, A.; Struthers, H.; Iversen, T.; Hansson, H.-C. et al. (14 March 2016). "Amplification of Arctic warming by past air pollution reductions in Europe" (in en). Nature Geoscience 9 (4): 277–281. doi:10.1038/ngeo2673. Bibcode: 2016NatGe...9..277A. https://www.nature.com/articles/ngeo2673.

- ↑ Harvey, C. (14 March 2016). "How cleaner air could actually make global warming worse". Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/energy-environment/wp/2016/03/14/how-cleaner-air-could-actually-make-global-warming-worse.

- ↑ Chylek, Petr; Folland, Chris K.; Lesins, Glen; Dubey, Manvendra K.; Wang, Muyin (16 July 2009). "Arctic air temperature change amplification and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation". Geophysical Research Letters 36 (14): L14801. doi:10.1029/2009GL038777. Bibcode: 2009GeoRL..3614801C.

External links

- Turton, Steve (3 June 2021). "Why is the Arctic warming faster than other parts of the world? Scientists explain". World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/climate-arctic-glacial-melt-rate.

|

KSF

KSF