Warming stripes

Topic: Earth

From HandWiki - Reading time: 27 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 27 min

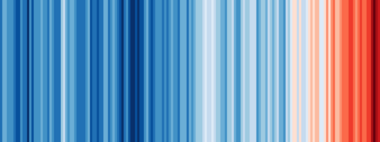

Warming stripes (sometimes referred to as climate stripes,[3][4][5][Note 1] climate timelines[6] or stripe graphics[7]) are data visualization graphics that use a series of coloured stripes chronologically ordered to visually portray long-term temperature trends.[2][Note 2] Warming stripes reflect a "minimalist"[2][5] style, conceived to use colour alone to avoid technical distractions to intuitively convey global warming trends to non-scientists.[8][9]

British climatologist Ed Hawkins originated the concept of visualizing historical temperature data in 2018.[1] The data visualization technique was soon extended to involve animation,[10] and to visualize diverse quantities such as sea level rise[11] predictive climate data,[12] progression of ocean depths,[13] aviation's greenhouse gas emissions,[14] biodiversity loss,[15] soil moisture changes[16] and fine particulate matter concentrations.[17] The graphic has been used to visually juxtapose temperature trends with other data—such as atmospheric CO

2 concentration,[18] global glacier retreat,[19] and precipitation.[4]

In less technical contexts, the graphic has been embraced by climate activists, used as cover images of books and magazines, used in fashion design, and projected onto natural landmarks.[20][21] It has been used on athletic team uniforms, music festival stages, and public infrastructure.[20][21]

Background, publication and content

— Ed Hawkins, May 2018

In May 2016, to make visualizing climate change easier for the general public, University of Reading climate scientist Ed Hawkins created an animated spiral graphic[26] of global temperature change as a function of time, a representation said to have gone viral.[9][27] Jason Samenow wrote in The Washington Post that the spiral graph was "the most compelling global warming visualization ever made",[28] before it was featured in the opening ceremony of the 2016 Summer Olympics.[10]

Separately, by 10 June 2017, Ellie Highwood, also a climate scientist at the University of Reading, had completed[29] a crocheted "global warming blanket"[20] that was inspired by "temperature blankets" representing temperature trends in respective localities.[30] Hawkins provided Highwood with a more user friendly colour scale to avoid the muted colour differences present in Highwood's blanket.[30] Independently, in November 2015, University of Georgia estuarine scientist Joan Sheldon made a "globally warm scarf" having 400 blue, red and purple rows, but could not contact Hawkins until 2022.[31] Both Highwood and Sheldon credit as their original inspirations, "sky blankets" and "sky scarves" which are based on daily sky colours.[32]

On 22 May 2018, Hawkins published[33] graphics constituting a chronologically ordered series of blue and red vertical stripes that he called warming stripes.[9] Hawkins, a lead author for the IPCC 6th Assessment Report, received the Royal Society's 2018 Kavli Medal, in part "for actively communicating climate science and its various implications with broad audiences".[34]

As described in a BBC article, in the month the big meteorological agencies release their annual climate assessments, Hawkins experimented with different ways of rendering the global data and "chanced upon the coloured stripes idea".[35] When he tried out a banner at the Hay Festival, according to the article, Hawkins "knew he'd struck a chord".[35] The National Centre for Atmospheric Science (UK), with which Hawkins is affiliated, states that the stripes "paint a picture of our changing climate in a compelling way. Hawkins swapped out numerical data points for colours which we intuitively react to".[6]

Others have called Hawkins's warming stripes "climate stripes"[3][4] or "climate timelines".[6]

Warming stripe graphics are reminiscent of colour field painting, a style prominent in the mid 20th century, which strips out all distractions and uses only colour to convey meaning.[8] A warming stripes graphic in a 2025 Museum of Modern Art exhibit has been compared to a painting by Morris Louis–one of the earliest proponents of the colour field monument.[36][37] Colour field pioneer Barnett Newman said he was "creating images whose reality is self-evident", an ethos that Hawkins is said to have applied to the problem of climate change.[8]

Collaborating with Berkeley Earth scientist Robert Rohde,[38] on 17 June 2019[2] Hawkins published for public use, a large set of warming stripes on ShowYourStripes.info.[39] Individualized warming stripe graphics were published for the globe, for most countries, as well as for certain smaller regions such as states in the US or parts of the UK,[40] since different parts of the world are warming more quickly than others.[41]

Data sources and data visualization

Warming stripe graphics are defined with various parameters, including:[33]

- source of dataset (meteorological organization)

- geographical scope of measurement (global, country, state, etc.)

- time period (year range, for horizontal "axis")

- temperature range (range of anomaly (deviation) about a reference or baseline temperature)

- colour palette (usually, shades of blue and red),

- colour scale (assignment of colours to represent respective ranges of temperature anomaly),

- temperature boundaries (temperature above which a stripe is red and below which is blue, usually determined by an average annual temperature over a "reference period" or "baseline" of usually 30 years).[48]

Hawkins' original graphics[Note 4] use the eight most saturated blues and reds from the ColorBrewer 9-class single hue palettes, which optimize colour palettes for maps and are noted for their colourblind-friendliness.[23] Hawkins said the specific colour choice was an aesthetic decision ("I think they look just right"), also selecting baseline periods to ensure equally dark shades of blue and red for aesthetic balance.[23] Hawkins chose the 1971-2000 average as a boundary between reds and blues because the average global temperature in that reference period represented the mid-point in the warming to date.[23]

A Republik analysis said that "this graphic explains everything in the blink of an eye", attributing its effect mainly to the chosen colors, which "have a magical effect on our brain, (letting) us recognize connections before we have even actively thought about them".[49] The analysis concluded that colors other than blue and red "don't convey the same urgency as (Hawkins') original graphic, in which the colors were used in the classic way: blue=cold, red=warm."[49]

ShowYourStripes.info cites dataset sources Berkeley Earth, NOAA, UK Met Office, MeteoSwiss, DWD (Germany),[40] specifically explaining that the data for most countries comes from the Berkeley Earth temperature dataset, except that for the US, UK, Switzerland & Germany the data comes from respective national meteorological agencies.[48]

For each country-level #ShowYourStripes graphic (Hawkins, June 2019), the average temperature in the 1971–2000 reference period is set as the boundary between blue (cooler) and red (warmer) colours, the colour scale varying +/- 2.6 standard deviations of the annual average temperatures between 1901 and 2000.[48][50] Hawkins noted in 2019 that the graphic for the Arctic "broke the colour scale" since it is warming more than twice as fast as the global average.[50] He later reported that the 2023 global average was so extreme that a new, darker shade of red was required.[24][51]

For statistical and geographic reasons, it is expected that graphics for small areas will show more year-to-year variation than those for large regions.[27] Year-to-year changes reflected in graphics for localities result from weather variability, whereas global warming over centuries reflects climate change.[46]

The NOAA website warns that the graphics "shouldn't be used to compare the rate of change at one location to another", explaining that "the highest and lowest values on the colour scale may be different at different locations".[4] Further, a certain colour in one graphic will not necessarily correspond to the same temperature in other graphics.[52][23]

A climate change denier generated a warming stripes graphic that misleadingly affixed Northern Hemisphere readings over one period to global readings over another period, and omitted readings for the most recent thirteen years, with some of the data being 29-year-smoothed—to give the false impression that recent warming is routine.[53] Calling the graphic "imposter warming stripes", meteorologist Jeff Berardelli described it in January 2020 as "a mishmash of data riddled with gaps and inconsistencies" with an apparent objective to confuse the public.[53]

Applications and influence

After Hawkins' first publication of warming stripe graphics in May 2018, broadcast meteorologists in multiple countries began to show stripe-decorated neckties, necklaces, pins and coffee mugs on-air, reflecting a growing acceptance of climate science among meteorologists and a willingness to communicate it to audiences.[59] In 2019, the United States House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis used warming stripes in its committee logo, showing horizontally oriented stripes behind a silhouette of the United States Capitol,[56] and three US Senators wore warming stripe lapel pins at the 2020 State of the Union Address.[60]

On 17 June 2019,[2] Hawkins initiated a social media campaign with hashtag #ShowYourStripes that encourages people to download their regions' graphics from ShowYourStripes.info, and to post them.[39] The campaign was backed by U.N. Climate Change, the World Meteorological Organization and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.[61] Called "a new symbol for the climate emergency" by French magazine L'EDN,[62] the graphics have been embraced by climate activists, used as cover images of books and magazines, used in fashion design, projected onto natural landmarks, and used on athletic team uniforms, music festival stages, and public infrastructure.[20]

More specifically, warming stripes have been applied to knit-it-yourself scarves,[63] a vase,[64] neckties, cufflinks, bath towels,[65] vehicles, and a music festival stage,[39] as well as on the side of Freiburg, Germany, streetcars,[66] as municipal murals in Córdoba, Spain,[67] Anchorage, Alaska,[68] and Jersey,[69] on face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic,[70] in an action logo of the German soccer club 1. FSV Mainz 05,[71] on the side of the Climate Change Observatory in Valencia,[72] on the side of a power station turbine house in Reading, Berkshire,[73] on tech-themed shirts,[74] on designer dresses,[75] on the uniforms of Reading Football Club,[76] on Leipzig's Sachsen Bridge,[58] on a biomethane-powered bus,[77] as a stage backdrop at the 2022 Glastonbury Festival,[78] on the racer uniforms and socks and webpage banner of the Climate Classic bicycle race,[21][79] on the World Bank's Climate Explainer Series,[80] projected onto the White Cliffs of Dover,[21][81] on an Envision Racing electric race car,[82] on numerous bridges and towers noted by Climate Central,[83] and in a logo of Climate Central itself.[84]

Remarking that "infiltrating popular culture is a means of triggering a change of attitude that will lead to mass action",[62] Hawkins surmised that making the graphics available for free has made them used more widely.[85] Hawkins further said that any merchandise-related profits are donated to charity.[85]

Through a campaign led by nonprofit Climate Central using hashtag #MetsUnite, more than 100 TV meteorologists—the scientists most laymen interact with more than any other[86]—featured warming stripes[39] and used the graphics to focus audience attention during broadcasts on summer solstices beginning in 2018[86][87] with the "Stripes for the Solstice" effort.[88]

On 24 June 2019, Hawkins tweeted that nearly a million stripe graphics had been downloaded by visitors from more than 180 countries[87] in the course of their first week.[89]

In 2018, the German Weather Service's meteorological training journal Promet showed a warming stripes graphic on the cover of the issue titled "Climate Communication".[90] By September 2019, the Met Office, the UK's national weather service, was using both a climate spiral and a warming stripe graphic on its "What is climate change?" webpage.[91] Concurrently, the cover of the 21–27 September 2019 issue of The Economist, dedicated to "The climate issue," showed a warming stripe graphic,[62][92][93] as did the cover of The Guardian on the morning of the 20 September 2019 climate strikes.[93] The environmental initiative Scientists for Future (2019) included warming stripes in its logo.[94] The Science Information Service (Germany) noted in December 2019 that warming stripes were a "frequently used motif" in demonstrations by the School strike for the climate and Scientists for Future, and were also on the roof of the German Maritime Museum in Bremerhaven.[95] Also in December 2019, Voilà Information Design said that warming stripes "have replaced the polar bear on a melting iceberg as the icon of the climate crisis".[23]

On 18 January 2020, a 20-metre-wide artistic light-show installation of warming stripes was opened at the Gendarmenmarkt in Berlin, with the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences building being illuminated in the same way.[96] The cover of the "Climate Issue" (fall 2020) of the Space Science and Engineering Center's Through the Atmosphere journal was a warming stripes graphic,[97] and in June 2021 the WMO used warming stripes to "show climate change is here and now" in its statement that "2021 is a make-or-break year for climate action".[61] The November 2021 UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) exhibited an immersive "climate canopy" sculpture consisting of hanging, blue and red color-coded, vertical lighted bars with fabric fringes.[98]

On 27 September 2019, the Fachhochschule (University of Applied Science) Potsdam announced that warming stripes graphics had won in the science category of an international competition recognising innovative and understandable visualisations of climate change,[66] the jury stating that the graphics make an "impact through their innovative, minimalist design".[5]

Hawkins was appointed Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in the 2020 New Year Honours "For services to Climate Science and to Science Communication".[99]

In April 2022, textiles from haute couture fashion designer Lucy Tammam with warming stripes won the Best Customer Engagement Campaign title in the Sustainable Fashion 2022 awards by Drapers fashion magazine.[100]

In October 2022, the front cover of Greta Thunberg's The Climate Book features warming stripes.[21][101][102]

In June 2023, Pope Francis was presented with a warming stripes stole.[21]

In May 2024, Hawkins received the Royal Geographical Society's Geographical Engagement Award for his work in developing warming stripes.[103]

In 2025, the warming stripes graphic was included in Engineering:Pirouette: Turning Points in Design, an exhibition of "widely recognized design icons" at the Museum of Modern Art highlighting design as an agent of change and "pivotal moments in design history."[104]

Extensions of warming stripes

In 2018, University of Reading post-doctoral research assistant Emanuele Bevacqua juxtaposed vertical-stripe graphics for CO

2 concentration and for average global temperature (August), and "circular warming stripes" depicting average global temperature with concentric coloured rings (November).[18]

In March 2019, German engineer Alexander Radtke extended Hawkins' historical graphics to show predictions of future warming through the year 2200, a graphic that one commentator described as making the future "a lot more visceral".[12] Radtke bifurcated the graphic to show diverging predictions for different degrees of human action in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[12]

On or before 30 May 2019, UK-based software engineer Kevin Pluck designed animated warming stripes that portray the unfolding of the temperature increase, allowing viewers to experience the change from an earlier stable climate to recent rapid warming.[10]

By June 2019, Hawkins vertically stacked hundreds of warming stripe graphics from corresponding world locations and grouped them by continent to form a comprehensive, composite graphic, "Temperature Changes Around the World (1901–2018)".[35][41]

On 1 July 2019, Durham University geography research fellow Richard Selwyn Jones published a Global Glacier Change graphic, modeled after and credited as being inspired by Hawkins' #ShowYourStripes graphics, allowing global warming and global glacier retreat to be visually juxtaposed.[19] Jones followed on 8 July 2019 with a stripe graphic portraying global sea level change using only shades of blue.[11] Separately, NOAA displayed a graphic juxtaposing annual temperatures and precipitation,[4] researchers from the Netherlands used stripe graphics to represent progression of ocean depths,[13] and the Institute of Physics used applied the graphic to represent aviation emission's percentage contribution to global warming.[14]

In 2023, University of Derby professor Miles Richardson created sequenced stripes to illustrate biodiversity loss,[15] and the German Meteorological Service represented soil moisture deviations using sequenced green and brown stripes.[16]

In August 2024, a collaboration among several universities and the UK Met Office published location-specific Air Quality Stripes having blue, yellow, orange, red and black stripes representing fine particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations over time.[17]

Critical response

Some warned that warming stripes of individual countries or states, taken out of context, could advance the idea that global temperatures are not rising,[39] though research meteorologist J. Marshall Shepherd said that "geographic variations in the graphics offer an outstanding science communication opportunity".[107] Meteorologist and #MetsUnite coordinator Jeff Berardelli said that "local stripe visuals help us tell a nuanced story—the climate is not changing uniformly everywhere".[108]

Others say the charts should include axes or legends,[39] though the website FAQ page explains the graphics were "specifically designed to be as simple as possible, and to start conversations... (to) fill a gap and enable communication with minimal scientific knowledge required to understand their meaning".[48] J. Marshall Shepherd, former president of the American Meteorological Society, lauded Hawkins' approach, writing that "it is important not to miss the bigger picture. Science communication to the public has to be different"[107] and commending Hawkins for his "innovative" approach and "outstanding science communication" effort.[39]

In The Washington Post, Matthew Cappucci wrote that the "simple graphics ... leave a striking visual impression" and are "an easily accessible way to convey an alarming trend", adding that "warming tendencies are plain as day".[3] Greenpeace spokesman Graham Thompson remarked that the graphics are "like a really well-designed logo while still being an accurate representation of very important data".[89]

CBS News contributor Jeff Berardelli noted that the graphics "aren't based on future projections or model assumptions" in the context of stating that "science is not left or right. It's simply factual."[3]

A September 2019 editorial in The Economist hypothesized that "to represent this span of human history (1850–2018) as a set of simple stripes may seem reductive"—noting those years "saw world wars, technological innovation, trade on an unprecedented scale and a staggering creation of wealth"—but concluded that "those complex histories and the simplifying stripes share a common cause," namely, fossil fuel combustion.[92]

Informally, warming stripes have been said to resemble "tie-dyed bar codes"[3] and a "work of art in a gallery".[109]

Writer Mark Feeney remarked that "seen in strictly visual terms, the graphic is quite pleasing to look at. It could be a Morris Louis painting. Understood conceptually, it’s alarming to contemplate."[37]

Similar graphics

The lobby of the MIT Museum has a sculpture made from thousands of feet of plastic twine, with each strand representing Earth's temperature going back to the ice age.[110] Blue and green strands reflect cooler climates than the reds and oranges.[110] The current temperature is represented by a single yellow piece of twine, and the sculpture then spreads out into a broad web representing possible futures with reds and blues.[110]

See also

Notes

- ↑ In his "Climate stripes for the UK" Climate Lab Book entry (17 September 2018), Ed Hawkins implicitly applied the generic term "climate stripes" to both temperature and rainfall graphics, reserving the more specific term "warming stripes" to the temperature graphic.

- ↑ More precisely: a warming stripes graphic generally portrays temperature anomalies, which are deviations below or above a chosen reference or baseline temperature.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Typically, warming stripe graphics portray temperature anomalies—usually, deviations from an average temperature over a chosen reference period (baseline)—and not absolute temperatures. Also, different graphics' colours may cover different-size temperature ranges (e.g., 0.10 °C per colour vs. 0.15 °C per colour). Accordingly, a particular colour in one graphic does not necessarily represent the same absolute temperature or temperature anomaly as the same colour in another graphic.

- ↑ In this Wikipedia article, some figures do not follow Hawkins' exact colour choice, as those figures were generated before the nature of Hawkins' chosen colour palette was widely publicized.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "2018 visualisation update / Warming stripes for 1850–2018 using the WMO annual global temperature dataset.". 4 December 2018. http://www.climate-lab-book.ac.uk/2018/2018-visualisation-update/. (Direct link to image).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "This Striking Climate Change Visualization Is Now Customizable for Any Place on Earth". 17 June 2019. https://earther.gizmodo.com/this-striking-climate-change-visualization-is-now-custo-1835581866.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "Show your stripes: These striking graphics that portray a warming climate are available for countries and regions". The Washington Post. 21 June 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2019/06/21/show-your-stripes-these-striking-graphics-that-portray-warming-climate-are-available-countries-regions/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 ""Climate stripes" graphics show U.S. trends by state and county". NOAA. 28 June 2019. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/features/climate-stripes-graphics-show-us-trends-state-and-county. Includes Jared Rennie's temperature-precipitation graphic (archive).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Visualisierungswettbewerb "Vis for Future" – das sind die Gewinner*innen" (in de). 27 September 2019. https://www.fh-potsdam.de/informieren/aktuelles/news-detailansicht/artikel/visualisierungswettbewerb-vis-for-future-das-sind-die-gewinnerinnen/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Ed Hawkins' warming stripes add colour to climate communication". UK. 2018. https://www.ncas.ac.uk/en/18-news/2935-ed-hawkin-s-warming-stripes-add-colour-to-climate-communication.

- ↑ "Show Your Stripes". Chicago, USA: The Climate Reality Project. 21 June 2019. https://climaterealitychicago.com/show-your-stripes/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 "This Climate Visualization Belongs in a Damn Museum". 25 May 2018. https://earther.gizmodo.com/this-climate-visualization-belongs-in-a-damn-museum-1826307536.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Staff, Science AF (25 May 2018). "This Has Got to Be One of The Most Beautiful And Powerful Climate Change Visuals We've Ever Seen". Science Alert. https://www.sciencealert.com/this-has-got-to-be-one-of-the-most-beautiful-and-powerful-climate-change-visuals-we-ve-ever-seen.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Why this climate change data is on flip-flops, leggings, and cars / Warming stripes keep showing up on clothes and crafts". Vox. 30 May 2019. https://www.vox.com/2019/3/4/18246245/climate-change-warming-stripes.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "One of the most striking trends – over a century of global-average sea level change.". Richard Selwyn Jones. 8 July 2019. https://twitter.com/selwynox/status/1148154450672050176. (link to image). For sea level change data, Jones cites "Sea-Level Rise from the Late 19th to the Early 21st Century". Surveys in Geophysics (Springer Netherlands) 32 (4–5): 585–602. September 2011. doi:10.1007/s10712-011-9119-1. Bibcode: 2011SGeo...32..585C. https://figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/Sea-level_rise_from_the_late_19th_to_the_early_21st_Century/22957013/1/files/40694336.pdf.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "New Climate Change Visualization Presents Two Stark Choices For Our Future". 20 March 2019. https://earther.gizmodo.com/new-climate-change-visualization-presents-two-stark-cho-1833443663.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Ecological consequences of sea level rise and flood protection strategies in shallow coastal systems: A quick-scan barcoding approach". Ocean & Coastal Management 210. 23 May 2021. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105674. Bibcode: 2021OCM...21005674T.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Aviation's present-day contribution to human-induced global warming is 4% and will increase over the next 30 years". Institute of Physics. 4 November 2021. https://phys.org/news/2021-11-aviation-present-day-contribution-human-induced-global.html.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Richardson, Miles (2023). "#BiodiversityStripes". University of Derby. https://biodiversitystripes.info/global.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Was Wir 2023 Über das Extremwetter in Deutschland Wissen (What We Know About Extreme Weather in Germany, 2023)". Deutscher Wetterdienst (German Meteorological Service). October 2023. p. 14. https://www.dwd.de/DE/klimaumwelt/aktuelle_meldungen/230927/Faktenpapier-Extremwetterkongress_download.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Air Quality Stripes". August 2024. https://airqualitystripes.info/.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "Climate Change Visualizations". November 2018. https://emanuele.bevacqua.eu/climatevisuals/. (University of Reading affiliate). (Author's link at University of Reading)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Inspired by @ed_hawkins #ShowYourStripes, here's 50 years of global glacier change!". Richard Selwyn Jones. 1 July 2019. https://twitter.com/selwynox/status/1145685364922880001.(). For temperature graphic Jones cites "Quantifying uncertainties in global and regional temperature change using an ensemble of observational estimates: The HadCRUT4 dataset". Journal of Geophysical Research 117 (D8). 17 April 2012. doi:10.1029/2011JD017187. Bibcode: 2012JGRD..117.8101M. For global glacier retreat graphic, Jones cites "Global glacier mass changes and their contributions to sea-level rise from 1961 to 2016". Nature 568 (7752): 382–386. 8 April 2019. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1071-0. PMID 30962533. Bibcode: 2019Natur.568..382Z. http://doc.rero.ch/record/324673/files/hus_ggm.pdf.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Rosch, Carla (10 December 2023). "The coloured stripes that explain climate change". BBC. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20231206-the-coloured-stripes-that-explain-climate-change.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 Igini, Martina (21 June 2024). "What the 'Warming Stripes' Tell Us About Climate Change". Earth.org. https://earth.org/showyourstripes-day-what-the-warming-stripes-tell-us-about-climate-change/.

- ↑ Data source: "Met Office Climate Dashboard / Global temperature / Global surface temperatures / (scroll down to) Berkeley Earth". Met Office (U.K.). January 2024. https://climate.metoffice.cloud/temperature.html. Data has been vertically offset to center trace vertically in chart.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 "Do you really understand the influential warming stripes?". 3 December 2019. https://www.chezvoila.com/blog/warmingstripes.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Stephens, Daisy (5 January 2024). "Climate stripes need new colour as world warms". BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c72yrd8y9pwo.

- ↑ "Double". 1999–2000. http://www.gabrieleevertz.com/index.html. (Wikimedia file page)

- ↑ "Global Temperature Change (1850–2016)". University of Reading. May 2016. http://blogs.reading.ac.uk/climate-lab-book/files/2016/05/spiral_optimized.gif. (Animated GIF.)

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 "The climate visualisations that leave no room for doubt or denial". The Spinoff (New Zealand). 17 September 2018. https://thespinoff.co.nz/science/17-09-2018/the-climate-visualisations-that-leave-no-room-for-doubt-or-denial/.

- ↑ "Unraveling spiral: The most compelling global warming visualization ever made". The Washington Post. 10 May 2016. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2016/05/10/the-most-compelling-visual-of-global-warming-ever-made/.

- ↑ "Ok so i am a crochet addict. This is my "global warming blanket" -stripes coloured according to last 100 years T anomaly.". 10 June 2017. https://twitter.com/elliehighwood/status/873603203279015937. (Tweet with image of "global warming blanket")

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 "The art of turning climate change science to a crochet blanket". European Geosciences Union. 15 June 2017. https://blogs.egu.eu/divisions/as/2017/06/15/the-art-of-turning-climate-change-science-to-a-crochet-blanket/.

- ↑ "The surprising story of 'warming stripes'". The New York Times. 17 June 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/17/climate/climate-warming-stripes.html.

- ↑ "Who really invented the climate stripes?". Canary Media. 3 June 2022. https://www.canarymedia.com/articles/climate-crisis/who-really-invented-the-climate-stripes.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "Warming stripes". UK. 22 May 2018. http://www.climate-lab-book.ac.uk/2018/warming-stripes/.

- ↑ "Our changing climate: learning from the past to inform future choices / Prize lecture". London: Royal Society. 30 April 2019. https://royalsociety.org/science-events-and-lectures/2019/04/kavli-lecture/. Hawkins described his climate spiral and warming stripes graphics in his Kavli prize lecture (video embedded in reference).

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 "The chart that defines our warming world / Is this the simplest way to show what is meant by global warming? The chart below organises all the countries of the world by region, time and temperature. The trend is unmistakeable.". BBC. 21 June 2019. https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-48678196. (Link to PNG image)

- ↑ "Designing for Climate Change". https://www.moma.org/magazine/articles/1212.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Feeney, Mark (23 July 2025). "At MoMA, designs for living". https://www.bostonglobe.com/2025/07/23/arts/moma-designs-living/.

- ↑ "From Dresses To Electric Cars, Why Are These Stripes All Over Social Media?". Forbes. 21 June 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidrvetter/2021/06/21/from-dresses-to-electric-cars-why-are-these-stripes-all-over-social-media/.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 "New climate 'stripes' reveal how much hotter your hometown has gotten in the past century". Science. 26 June 2019. https://www.science.org/content/article/new-climate-stripes-reveal-how-much-hotter-your-hometown-has-gotten-past-century.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 "#ShowYourStripes (main web page)". https://showyourstripes.info/.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "This is one of the simplest and best climate change graphics we've ever seen". Fast Company. 21 June 2019. https://www.fastcompany.com/90367577/this-is-one-of-the-simplest-and-best-climate-change-graphics-weve-ever-seen.

- ↑ "Climate at a Glance / Global Time Series". NOAA (National Centers for Environmental Information; National Climatic Data Center). December 2018. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/global/time-series/nhem/land_ocean/12/12/1880-2019. Choose 12-Month timescale, December 1880–2019, Northern Hemisphere, Land and Ocean, Plot.

- ↑ "Climate at a Glance / Global Time Series". NOAA (National Centers for Environmental Information; National Climatic Data Center). December 2018. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/global/time-series/shem/land_ocean/12/12/1880-2019. Choose 12-Month timescale, December 1880–2019, Southern Hemisphere, Land and Ocean, Plot.

- ↑ "Climate at a Glance / Global Time Series". NOAA (National Centers for Environmental Information; National Climatic Data Center). December 2018. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/global/time-series/globe/land_ocean/12/12/1880-2019. Choose 12-Month timescale, December 1880–2019, Global, Land and Ocean, Plot.

- ↑ "Climate at a Glance / Global Time Series". NOAA (National Centers for Environmental Information; National Climatic Data Center). December 2018. https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/global/time-series/caribbeanIslands/land_ocean/12/12/1880-2019. Choose 12-Month timescale, December 1880–2019, Caribbean Islands, Land and Ocean, Plot.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 "Warming Stripes: Global". NOAA (Science on a Sphere). 7 February 2019. https://sos.noaa.gov/datasets/warming-stripes-global/.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 "Land + Ocean (1850 – Recent) / Monthly Global Average Temperature (annual summary)". Berkeley Earth. 2019. http://berkeleyearth.lbl.gov/auto/Global/Land_and_Ocean_summary.txt. Data is based an average of "Annual Anomaly" from under "Land + Ocean anomaly using air temperature above sea ice" and from under "Land + Ocean using water temperature below sea ice", and adjusted to have a reference period (baseline) of 1961–1990 for comparison purposes.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 "#ShowYourStripes / FAQ Page". https://showyourstripes.info/faq.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 "Die schönste Klimagrafik der Welt" (in de). Republik.ch. 8 April 2019. https://www.republik.ch/2019/04/08/die-schoenste-klimagrafik-der-welt.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 "Show Your Stripes". World Meteorological Organization. 20 June 2019. https://public-old.wmo.int/en/media/news/show-your-stripes-0.

- ↑ "Show your stripes 2024: a darker shade of red". Royal Meteorological Society. 20 June 2024. https://www.rmets.org/metmatters/show-your-stripes-2024-darker-shade-red.

- ↑ "Global warming: Can these striking charts convince nay-sayers?". New Atlas. 19 June 2019. https://newatlas.com/global-warming-visualization/60210/.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "2,000 years of Earth's climate in one simple chart – and the copycat that isn't what it seems". CBS News. 30 January 2020. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/climate-change-2000-years-of-earths-temperatures-in-one-simple-chart-and-copycat-misinformation/.

- ↑ Hawkins, Ed; Williams, Richard G.; Young, Paul J.; Berardelli, Jeff; Burgess, Samantha N.; Highwood, Ellie; Randel, William; Roussenov, Vassil et al. (1 May 2025). "Warming Stripes Spark Climate Conversations: From the Ocean to the Stratosphere". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 6 (5): E964–E970. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-24-0212.1. Bibcode: 2025BAMS..106E.964H.

- ↑ "Atmospheric temperature trends". 12 September 2019. http://www.climate-lab-book.ac.uk/2019/atmospheric-temperature-trends/. (Higher-altitude cooling differences attributed to ozone depletion and greenhouse gas increases; spikes occurred with volcanic eruptions of 1982–1983 (El Chichón) and 1991–1992 (Pinatubo).)

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 "United States House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis / About". United States House of Representatives. 2019. https://climatecrisis.house.gov/about. Crediting Shawna Faison and House Creative Services.

- ↑ "Kooky the climate activist Kookaburra visits the UNFCCC pavillion [sic"]. 6 December 2019. https://www.flickr.com/photos/takver/49207825152/.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Warming Stripes auf der Sachsenbrücke" (in de). April 2022. https://sachsenbruecke.de/.

- ↑ "Why are more than 100 television meteorologists around the world wearing this tie?". The Washington Post. 21 June 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2018/06/21/why-are-over-100-television-meteorologists-around-the-world-wearing-this-tie/.

- ↑ "Climate change: Why are US senators wearing this symbol?". BBC. 9 February 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/science-environment-51418310/climate-change-why-are-us-senators-wearing-this-symbol.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "Warming stripes show that climate change is here and now". World Meteorological Organization. 21 June 2021. https://wmo.int/media/news/warming-stripes-show-climate-change-here-and-now.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 "Réchauffement climatique : ce graphique scientifique fait le buzz" (in fr). L'EDN. 23 September 2019. https://www.ladn.eu/mondes-creatifs/rechauffement-climatique-graphique-buzz/.

- ↑ "Dieser selbst gestrickte Schal zeigt, wie sehr sich die Erde in 138 Jahren erwärmt hat" (in de). ze.tt (Zeit Online partner) (Germany). 12 December 2019. https://ze.tt/dieser-selbst-gestrickte-schal-zeigt-wie-sehr-sich-die-erde-in-138-jahren-erwaermt-hat/.

- ↑ "Vase Inspired by Viral Climate Change Graphic". Woolley and Wallis (auctioneer). 21 November 2019. https://www.woolleyandwallis.co.uk/news/news/vase-inspired-by-viral-climate-change-graphic/.

- ↑ "Klimatuch 2214: Durchschnittliche Temperaturveränderung von 1850 bis 2021 / Jede Linie steht für ein Jahr / Global temperature change - So sieht die Klimaerwärmung aus! Velourqualität, 500g/m², 100% Baumwolle" (in de). HERKA Frottier. Kautzen, Austria: Herka GmbH. 2022. https://www.herka-frottier.at/shop/neuheiten-2021/klimatuch/.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "Die besten Darstellungen des Klimawandels" (in de). Tagesspiegel. 27 September 2019. https://digitalpresent.tagesspiegel.de/vis-for-future.

- ↑ "El código climático o la huella del alza de las temperaturas hecha color" (in es). El Diario. 7 October 2019. https://www.eldiario.es/andalucia/sostenibilidad/codigo-climatico-huella-temperaturas-hecha_0_945256358.html.

- ↑ "Anchorage public art depicts changing temperatures". Travel Weekly. 26 May 2020. https://www.travelweekly.com/North-America-Travel/Anchorage-public-art-depicts-changing-temperatures.

- ↑ Newsdesk (24 September 2023). "Climate change denier who damaged St Helier mural loses appeal". Jersey Evening Post. https://jerseyeveningpost.com/news/2023/09/24/climate-change-denier-who-damaged-st-helier-mural-loses-appeal/.

- ↑ "Face masks show Earth's grim warming trend". 12 May 2020. https://mashable.com/article/face-mask-coronavirus-climate-change/.

- ↑ "05ER Klimaverteidiger-Woche: Neue Anspruch Durch Neue Berechnung" (in de). 7 October 2020. https://www.mainz05.de/news/05er-klimaverteidiger-woche-neuer-anspruch-durch-neue-berechnung/.

- ↑ "El Ayuntamiento de València refuerza el trabajo del Observatorio del Cambio Climático con más presupuesto y personal para incidir en educación, formación y concienciación" (in es). El Periodic. 26 January 2021. https://www.elperiodic.com/valencia/ayuntamiento-valencia-refuerza-trabajo-observatorio-cambio-climatico-presupuesto-personal-para-incidir-educacion-formacion-concienciacion_725287.

- ↑ "Reading Hydro Murals". Reading Hydro. 2021. https://readinghydro.org/mural/. (link to image)

- ↑ "800,000 years of data, 1 clear message". FashionUnited. 1 June 2021. https://fashionunited.uk/news/fashion/800-000-years-of-data-1-clear-message/2021060155771.

- ↑ "Climate Stripes 12 Way Dress". 22 June 2021. https://www.tammam.co.uk/rtw/p/stripe-12-way.

- ↑ "Reading make climate change statement with eye-catching new home kit, which features stripes showing how temperatures are rising over time". 25 July 2022. https://talksport.com/football/efl/1156814/reading-climate-change-home-kit-stripes-temperatures-rising/.

- ↑ "Reading Buses teams up with University of Reading to launch climate stripes bus (and yes, it is eco-friendly)". Reading Today. 6 August 2022. https://rdg.today/reading-buses-teams-up-with-university-of-reading-to-launch-climate-stripes-bus-and-yes-it-is-eco-friendly/.

- ↑ "Greta Thunberg delivers a climate warning at Glastonbury". BBC. 25 June 2022. https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-61938933.

- ↑ "De Uitdaging Voor Duurzame Impact (The Challenge for Sustainable Impact)" (in Dutch). 2022. https://cycling4climate.nl/.

- ↑ "Climate Explainer Series". World Bank. 17 October 2022. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2022/10/17/what-you-need-to-know-about-food-security-and-climate-change.

- ↑ Fuller, Christian (21 June 2023). "Climate change warning beamed on Dover's White Cliffs". BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cjqz1xnjydgo.

- ↑ "Envision Racing Launches Iconic Climate Stripes on Race Car at COP28". Envision Racing. 8 December 2023. https://envision-racing.com/envision-racing-launches-iconic-climate-stripes-on-race-car-at-cop28/.

- ↑ "Stripes Day on June 21st". Climate Central. June 2023. https://www.climatecentral.org/stripes-information.

- ↑ "Climate Central (logo on Instagram)". Climate Central. https://www.instagram.com/climatecentral/.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "How a climate crisis graphic became a meme". 25 September 2019. https://www.designweek.co.uk/issues/23-29-september-2019/climate-change-graphic/.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 "Summer is officially here — time to show your stripes for climate change". The Boston Globe. 21 June 2019. https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2019/06/21/summer-officially-here-time-show-your-stripes-for-climate-change/2c1k3ukCMD2nT5xYqqZOEL/story.html.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 "TV meteorologists kicked off the summer by talking about climate change / #MetsUnite and #ShowYourStripes campaign highlighted the importance of climate communication". Media Matters. 25 June 2019. https://www.mediamatters.org/blog/2019/06/25/TV-meteorologists-kicked-off-the-summer-by-talking-about-climate-change/224036.

- ↑ "Why TV Meteorologists Will 'Show Their Stripes' For Climate On June 21st". Forbes. 19 June 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/marshallshepherd/2019/06/19/why-tv-meteorologists-will-show-their-stripes-for-climate-on-june-21st/.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 "Musicians to TV presenters show their stripes as climate campaign goes viral". Reuters. 28 June 2019. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-environment-climate-stripes/musicians-to-tv-presenters-show-their-stripes-as-climate-campaign-goes-viral-idUSKCN1TT2SO.

- ↑ ""Promet"-Themenheft zur Klimakommunikation" (in de). 26 September 2018. https://www.dwd.de/DE/klimaumwelt/aktuelle_meldungen/181126/promet_klimakommunikation.html.

- ↑ "What is climate change? / How fast is the temperature rising?". United Kingdom. September 2019. https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/weather/learn-about/climate-and-climate-change/climate-change/index. Climate spiral does not appear in full in archive for some reason; it's before the caption that includes "... The temperature increases as you move away from the centre of the circle."

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 "The climate issue". The Economist. 19 September 2019. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/09/19/the-climate-issue. (archived announcement).

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 "Climate strikes expected to be largest environmental protest in history". 20 September 2019. https://www.carbonbrief.org/daily-brief/climate-strikes-expected-to-be-largest-environmental-protest-in-history.

- ↑ "Warnt die Bahn in Cottbus vor dem Klimawandel? / Bahnhofs-Fassade zeigt Erderwärmung" (in de). B.Z. (Berlin, Germany: Axel Springer SE). 10 June 2020. https://www.bz-berlin.de/berlin/umland/warnt-die-bahn-in-cottbus-vor-dem-klimawandel.

- ↑ "Ed Hawkins Warming Stripes on the Roof of the German Maritime Museum". IDW (Informationsdienst Wissenschaft; Scientific Information Service). Germany. 2 December 2019. https://idw-online.de/de/news728235.

- ↑ "Claypaky Xtylos and Warming Stripes". Light and Sound Journal. 5 March 2020. https://www.lightsoundjournal.com/2020/03/05/claypaky-xtylos-and-warming-stripes/.

- ↑ "Through the Atmosphere Fall 2020, The Climate Issue". Space Science and Engineering Center. 19 November 2020. https://www.ssec.wisc.edu/news/articles/13301.

- ↑ "Climate Canopy exhibit displays global warming in new light". National Centre for Atmospheric Science. 13 October 2021. https://ncas.ac.uk/climate-canopy-exhibit-displays-global-warming-in-new-light/. (archive of related video)

- ↑ No. 62866. 28 December 2019. p. N18. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/62866/supplement/N18 Archived from the original on 28 December 2019.

- ↑ IED News Desk (29 April 2022). "University Of Reading: Climate Change Fashion Wins Sustainability Award". India Education Diary. https://indiaeducationdiary.in/university-of-reading-climate-change-fashion-wins-sustainability-award/.

- ↑ "Allen Lane reveals Greta Thunberg cover featuring Hawkins 'Warming Stripes' graph". The Bookseller. 26 May 2022. https://www.thebookseller.com/news/allen-lane-reveals-greta-thunberg-cover-featuring-hawkins-warming-stripes-graph.

- ↑ Thunberg, Greta, ed (2022-10-28). The Climate Book (1 ed.). London, UK: allen lane / Penguin Books / Penguin Random House. ISBN 978-0-241-54747-2. OCLC 1338161907. (2+18+446+2 pages) (NB. For space reasons references are not included in the printed book, but can be found online at: https://theclimatebook.org.)

- ↑ "Society's 2024 medal and award recipients announced". Royal Geographical Society. 7 May 2024. https://www.rgs.org/about-us/our-work/latest-news/societys-2024-medal-and-award-recipients-announced.

- ↑ "Pirouette: Turning Points in Design / January 26, 2025 – October 18, 2025". Museum of Modern Art. October 2024. https://press.moma.org/exhibition/pirouette/.

- ↑ "#ShowYourStripes / Temperature changes around the world (1901–2018)". 21 July 2019. http://www.climate-lab-book.ac.uk/2019/showyourstripes/#more-5629. (Direct link to image).

- ↑ "Average World Temperature Since 1850". 15 June 2016. https://www.reddit.com/r/dataisbeautiful/comments/4o6if2/the_temperature_of_the_world_since_1850_oc/?sort=old. Data source: University of East Anglia Climate Research Unit (CRU) (archive).

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 "Why Science For The Public Has To Be Different". Forbes. 24 June 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/marshallshepherd/2019/06/24/why-science-for-the-public-has-to-be-different/.

- ↑ "Show Your Stripes: Iconic Global Warming Imagery Goes Local". Weather Underground. 20 June 2019. https://www.wunderground.com/cat6/Show-Your-Stripes-Iconic-Global-Warming-Imagery-Goes-Local.

- ↑ "'Warming stripes' show how Australia's average temperatures have changed". News.com (Australia). 29 August 2018. https://www.news.com.au/technology/environment/warming-stripes-show-how-australias-average-temperatures-have-changed/news-story/3e4d898ff05a217548db0b5ba6715961.

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 110.2 Segran, Elizabeth (23 September 2025). "This stunning new sculpture visualizes what climate change could do to the Earth". Fast Company. https://www.fastcompany.com/91403726/this-stunning-new-sculpture-visualizes-what-climate-change-could-do-to-the-earth.

Further reading

- "The story behind the viral graphic that electrified the climate movement". Fast Company. 20 September 2019. https://www.fastcompany.com/90405797/the-story-behind-the-viral-graphic-that-electrified-the-climate-movement.

- Hawkins, Ed; Williams, Richard G.; Young, Paul J.; Berardelli, Jeff; Burgess, Samantha N.; Highwood, Ellie; Randel, William; Roussenov, Vassil et al. (1 May 2025). "Warming Stripes Spark Climate Conversations: From the Ocean to the Stratosphere". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 6 (5): E964–E970. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-24-0212.1. Bibcode: 2025BAMS..106E.964H. — historical summary, applications, scientific underpinnings

- "Annual United States Climate Stripes: Temperature and Precipitation". North Carolina State University. https://ncsu.maps.arcgis.com/apps/MapSeries/index.html?appid=a414fcbe90fb4dedaab06a8abf12b1a0. — clickable map of warming stripes for each county in 48 contiguous US states

- "On Inconvenient Images: Exploring the Design Space of Engaging Climate Change Visualizations for Public Audiences". Workshop on Visualisation in Environmental Sciences (EnvirVis) (The Eurographics Association): 1–8. 2019. doi:10.2312/envirvis.20191098. ISBN 978-3-03868086-4. https://www.academia.edu/39733782. — Survey of climate change visualizations

External links

- ShowYourStripes.info — warming stripes portraying historical data for multiple locations

- Ed Hawkins. Warming Stripes, 1850-2023. 2018–ongoing MoMA audio narrated by Hawkins

|

KSF

KSF