Zealandia

Topic: Earth

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 9 min

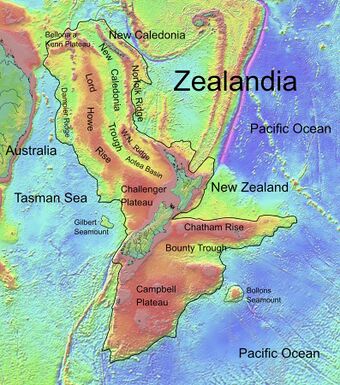

Zealandia (pronounced /ziːˈlændiə/), also known as Te Riu-a-Māui (Māori)[1] or Tasmantis (from Tasman Sea),[2][3] is an almost entirely submerged mass of continental crust in Oceania that subsided after breaking away from Gondwana 83–79 million years ago.[4] It has been described variously as a submerged continent, continental fragment, and microcontinent.[5] The name and concept for Zealandia was proposed by Bruce Luyendyk in 1995,[6] and satellite imagery shows it to be almost the size of Australia.[7] A 2021 study suggests Zealandia is over a billion years old, about twice as old as geologists previously thought.[8][9]

By approximately 23 million years ago, the landmass may have been completely submerged.[10][11] Today, most of the landmass (94%) remains submerged beneath the Pacific Ocean.[12] New Zealand is the largest part of Zealandia that is above sea level, followed by New Caledonia.

Mapping of Zealandia concluded in 2023.[13] With a total area of approximately 4,900,000 km2 (1,900,000 sq mi),[5] Zealandia is substantially larger than any features termed microcontinents and continental fragments. If classified as a microcontinent, Zealandia would be the world's largest microcontinent. Its area is six times the area of the next-largest microcontinent, Madagascar,[5] and more than half the exposed land area of the Australian continent. Zealandia is more than twice the size of the largest intraoceanic large igneous province (LIP) in the world, the Ontong Java Plateau (approximately 1,900,000 km2 or 730,000 sq mi), and the world's largest island, Greenland (2,166,086 km2 or 836,330 sq mi). Zealandia is also substantially larger than the Arabian Peninsula (3,237,500 km2 or 1,250,000 sq mi), the world's largest peninsula, and the Indian subcontinent (4,300,000 km2 or 1,700,000 sq mi). Due to these and other geological considerations, such as crustal thickness and density,[14][15] some geologists from New Zealand, New Caledonia, and Australia have concluded that Zealandia fulfills all the requirements to be considered a continent rather than a microcontinent or continental fragment.[5] Geologist Nick Mortimer commented that if it were not for the ocean level, it would have been recognised as such long ago.[16]

Zealandia supports substantial inshore fisheries and contains gas fields, of which the largest known is the New Zealand Maui gas field, near Taranaki. Permits for oil exploration in the Great South Basin were issued in 2007.[17] Offshore mineral resources include ironsands, volcanic massive sulfides and ferromanganese nodule deposits.[18]

Etymology

GNS Science recognises two names for the landmass. In English, the most common name is Zealandia, a latinate name for New Zealand; the name was coined in the mid-1990s and became established through common use. In the Māori language, the landmass is named Te Riu-a-Māui, meaning 'the hills, valleys, and plains of Māui'.[1]

Geology

{{#section-h:Geology of Zealandia|Geology}}

Biogeography

New Caledonia is at the northern end of the ancient continent, while New Zealand rises at the plate boundary that bisects it. These land masses constitute two outposts of the Antarctic flora, featuring araucarias and podocarps. At Curio Bay, logs of a fossilized forest closely related to modern kauri and Norfolk pine can be seen that grew on Zealandia approximately 180 million years ago during the Jurassic period, before it split from Gondwana.[19] The trees growing in these forests were buried by volcanic mud flows and gradually replaced by silica to produce the fossils now exposed by the sea.

As sea levels drop during glacial periods, more of Zealandia becomes a terrestrial environment rather than a marine environment. Originally, it was thought that Zealandia had no native land mammal fauna, but the discovery in 2006 of a fossil mammal jaw from the Miocene in the Otago region demonstrates otherwise.[20]

Political divisions

Template:More sources needed section

The total land area (including inland water bodies) of Zealandia is 286,660.25 km2 (110,680.14 sq mi). Of this, New Zealand comprises the overwhelming majority, at 267,988 km2 (103,471 sq mi, or 93.49%) that includes the mainland (North Island and South Island), nearby islands, and most outlying islands, including the Chatham Islands, the New Zealand Subantarctic Islands, the Solander Islands, and the Three Kings Islands (but not the Kermadec Islands or Macquarie Island (Australia), which are parts of the rift).[21]

New Caledonia and the islands surrounding it comprise some 18,576 km2 (7,172 sq mi or 6.48%) and the remainder is made up of various territories of Australia including the Lord Howe Island Group (New South Wales) at 56 km2 (22 sq mi or 0.02%), Norfolk Island at 35 km2 (14 sq mi or 0.01%), as well as the Cato, Elizabeth, and Middleton reefs (Coral Sea Islands Territory) with 5.25 km2 (2.03 sq mi).[21][22]

Population

As of 2024,[update] the total human population of Zealandia is approximately 5.4 million people. The largest city is Auckland with about 1.7 million people; roughly one-third of the total population of the continent.

New Zealand – 5,112,300[23]

New Zealand – 5,112,300[23] New Caledonia (France) – 268,767[24]

New Caledonia (France) – 268,767[24] Norfolk Island (Australia) – 1,748[25]

Norfolk Island (Australia) – 1,748[25]- Template:Country data Lord Howe Island (Australia) – 382[26]

- Template:Country data Coral Sea Islands Cato Reef (Australia) – 0

- Template:Country data Coral Sea Islands Elizabeth Reef (Australia) – 0

- Template:Country data Coral Sea Islands Middleton Reef (Australia) – 0

See also

- Australia (continent)

- Exclusive economic zone of New Zealand

- New Zealand Subantarctic Islands

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "The origin and meaning of the name Te Riu-a-Māui/Zealandia". GNS Science. 2 May 2019. https://www.gns.cri.nz/Home/News-and-Events/What-s-new/The-origin-and-meaning-of-the-name-Te-Riu-a-Maui-Zealandia.

- ↑ Flannery, Tim (2002) (in en). The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People. Grove Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-8021-3943-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=eIW5aktgo0IC&pg=PA42. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ↑ Danver, Steven L. (22 December 2010). Popular Controversies in World History: Investigating History's Intriguing Questions. ABC-CLIO. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-59884-078-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=slVobUjdzGMC&q=%22Zealandia%22+%22Tasmantis%22&pg=PA187. "Zealandia or Tasmantis, with its 3.5 million square km territory being larger than Greenland, ..."

- ↑ Gurnis, M.; Hall, C.E.; Lavier, L.L. (2004). Evolving force balance during incipient subduction: Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, v. 5, Q07001. https://doi.org/10.01029/02003GC000681.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedmortimer - ↑ Luyendyk, Bruce P. (April 1995). "Hypothesis for Cretaceous rifting of east Gondwana caused by subducted slab capture". Geology 23 (4): 373–376. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0373:HFCROE>2.3.CO;2. Bibcode: 1995Geo....23..373L.

- ↑ Gorvett, Zaria (8 February 2021). "The missing continent it took 375 years to find". BBC. https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20210205-the-last-secrets-of-the-worlds-lost-continent.

- ↑ Turnbull, R.E.; Schwartz, J.J.; Fiorentini, M.L.; Jongens, R.; Evans, N.J.; Ludwig, T.; McDonald, B.J.; Klepeis, K.A. (2021-08-01). "A hidden Rodinian lithospheric keel beneath Zealandia, Earth's newly recognized continent" (in en). Geology 49 (8): 1009–1014. doi:10.1130/G48711.1. ISSN 0091-7613. Bibcode: 2021Geo....49.1009T.

- ↑ Aylin Woodward (14 Aug 2021). "A fragment of a mysterious 8th continent is hiding under New Zealand - and it's twice as old as scientists thought". https://www.businessinsider.com/hidden-continent-zealandia-under-new-zealand-age-map-2021-7.

- ↑ "Searching for the lost continent of Zealandia". The Dominion Post. 29 September 2007. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/31306/Searching-for-the-lost-continent-of-Zealandia. "We cannot categorically say that there has always been land here. The geological evidence at present is too weak, so we are logically forced to consider the possibility that the whole of Zealandia may have sunk."

- ↑ Campbell, Hamish; Gerard Hutching (2007). In Search of Ancient New Zealand. North Shore, New Zealand: Penguin Books. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-14-302088-2.

- ↑ Wood, Ray; Stagpoole, Vaughan; Wright, Ian; Davy, Bryan; Barnes, Phil (2003). New Zealand's Continental Shelf and UNCLOS Article 76. Institute of Geological and Nuclear Sciences series 56. Wellington, New Zealand: National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. p. 16. NIWA technical report 123. https://www.gns.cri.nz/research/marine/images/unclosbook_print.pdf. Retrieved 22 February 2007. "The continuous rifted basement structure, thickness of the crust, and lack of seafloor spreading anomalies are evidence of prolongation of the New Zealand land mass to Gilbert Seamount."

- ↑ Newcomb, Tim. "Earth's Hidden Eighth Continent Is No Longer Lost" (in en-US). Popular Mechanics. ISSN 0032-4558. https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/environment/a45226285/eighth-continent-zealandia-mapped/.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMortimerCampbell2014 - ↑ "Zealandia: Is there an eighth continent under New Zealand?" (in en-GB). BBC News. 2017-02-17. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-39000936.

- ↑ Sumner, Thomas (2017-03-13). "Is Zealandia a continent?". Science News for Students. Society for Science and the Public. https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/zealandia-continent.

- ↑ "Great South Basin – Questions and Answers". 11 July 2007. https://www.crownminerals.govt.nz/cms/about/media-centre/great-south-basin-media-pack-1/great-south-basin-questions-and-answers.

- ↑ "New survey published on NZ mineral deposits". 30 May 2007. https://www.crownminerals.govt.nz/cms/news/2006/new-survey-published-on-nz-mineral-deposits.

- ↑ "Fossil forest: Features of Curio Bay/Porpoise Bay". https://www.doc.govt.nz/templates/page.aspx?id=35598.

- ↑ Campbell, Hamish; Gerard Hutching (2007). In Search of Ancient New Zealand. North Shore, New Zealand: Penguin Books. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-14-302088-2.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "The Lost Continent of Zealandia". https://www.virtualoceania.net/newzealand/maps/zealandia.shtml#:~:text=Zealandia,%20The%20Hidden%20Continent&text=This%20opens%20in%20a%20new,sq%20mi%20or%2093%25)..

- ↑ "Detailed map of Zealandia". https://data.gns.cri.nz/tez/index.html?map=TRAMZ-Bathymetric.

- ↑ "Population | Stats NZ". https://www.stats.govt.nz/topics/population.

- ↑ "268 767 habitants en 2014.". ISEE. http://www.isee.nc/population/recensement/structure-de-la-population-et-evolutions.

- ↑ "2016 Census QuickStats: Norfolk Island" (in en). https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SSC90004?opendocument.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics (27 June 2017). "Lord Howe Island (State Suburb)". 2016 Census QuickStats. http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/SSC12387.

External links

- "Zealandia: Earth's Hidden Continent". https://www.geosociety.org/gsatoday/archive/27/3/article/GSATG321A.1.htm.

- "E Tūhura - Explore Zealandia A portal for geoscience webmaps and information on the Te Riu-a-Māui / Zealandia region". https://data.gns.cri.nz/tez/index.html?content=/mapservice/Content/Zealandia/Home.html.

- "Zealandia: the New Zealand (drowned) Continent". http://www.teara.govt.nz/EarthSeaAndSky/OceanStudyAndConservation/SeaFloorGeology/1/en.

- Zealandia (National Geographic Encyclopedia)

- Is Zealandia a continent?

- The missing continent that took 375 years to find, by Zaria Gorvett, 7 February 2021, BBC website.

- Earth Has a Hidden 8th Continent, by Tia Ghose published 17 February 2017, Live Science website.

[ ⚑ ] 40°S 170°E / 40°S 170°E

|

KSF

KSF