End (graph theory)

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 10 min

In the mathematics of infinite graphs, an end of a graph represents, intuitively, a direction in which the graph extends to infinity. Ends may be formalized mathematically as equivalence classes of infinite paths, as havens describing strategies for pursuit–evasion games on the graph, or (in the case of locally finite graphs) as topological ends of topological spaces associated with the graph. Ends of graphs may be used (via Cayley graphs) to define ends of finitely generated groups. Finitely generated infinite groups have one, two, or infinitely many ends, and the Stallings theorem about ends of groups provides a decomposition for groups with more than one end.

Definition and characterization

Ends of graphs were defined by Rudolf Halin (1964) in terms of equivalence classes of infinite paths.[1] A ray in an infinite graph is a semi-infinite simple path; that is, it is an infinite sequence of vertices in which each vertex appears at most once in the sequence and each two consecutive vertices in the sequence are the two endpoints of an edge in the graph. According to Halin's definition, two rays and are equivalent if there is a ray (which may equal one of the two given rays) that contains infinitely many of the vertices in each of and . This is an equivalence relation: each ray is equivalent to itself, the definition is symmetric with regard to the ordering of the two rays, and it can be shown to be transitive. Therefore, it partitions the set of all rays into equivalence classes, and Halin defined an end as one of these equivalence classes.[2]

An alternative definition of the same equivalence relation has also been used: two rays and are equivalent if there is no finite set of vertices that separates infinitely many vertices of from infinitely many vertices of .[3] This is equivalent to Halin's definition: if the ray from Halin's definition exists, then any separator must contain infinitely many points of and therefore cannot be finite, and conversely if does not exist then a path that alternates as many times as possible between and must form the desired finite separator.

Ends also have a more concrete characterization in terms of havens, functions that describe evasion strategies for pursuit–evasion games on a graph .[4] In the game in question, a robber is trying to evade a set of policemen by moving from vertex to vertex along the edges of . The police have helicopters and therefore do not need to follow the edges; however the robber can see the police coming and can choose where to move next before the helicopters land. A haven is a function that maps each set of police locations to one of the connected components of the subgraph formed by deleting ; a robber can evade the police by moving in each round of the game to a vertex within this component. Havens must satisfy a consistency property (corresponding to the requirement that the robber cannot move through vertices on which police have already landed): if is a subset of , and both and are valid sets of locations for the given set of police, then must be a superset of . A haven has order if the collection of police locations for which it provides an escape strategy includes all subsets of fewer than vertices in the graph; in particular, it has order (the smallest aleph number) if it maps every finite subset of vertices to a component of . Every ray in corresponds to a haven of order , namely, the function ; that maps every finite set to the unique component of that contains infinitely many vertices of the ray. Conversely, every haven of order can be defined in this way by a ray.[5] Two rays are equivalent if and only if they define the same haven, so the ends of a graph are in one-to-one correspondence with its havens of order .[4]

Examples

If the infinite graph is itself a ray, then it has infinitely many ray subgraphs, one starting from each vertex of . However, all of these rays are equivalent to each other, so only has one end.

If is a forest (that is, a graph with no finite cycles), then the intersection of any two rays is either a path or a ray; two rays are equivalent if their intersection is a ray. If a base vertex is chosen in each connected component of , then each end of contains a unique ray starting from one of the base vertices, so the ends may be placed in one-to-one correspondence with these canonical rays. Every countable graph has a spanning forest with the same set of ends as .[6] However, there exist uncountably infinite graphs with only one end in which every spanning tree has infinitely many ends.[7]

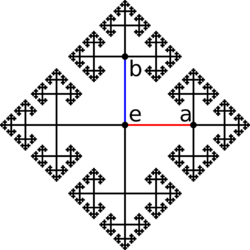

If is an infinite grid graph, then it has many rays, and arbitrarily large sets of vertex-disjoint rays. However, it has only one end. This may be seen most easily using the characterization of ends in terms of havens: the removal of any finite set of vertices leaves exactly one infinite connected component, so there is only one haven (the one that maps each finite set to the unique infinite connected component).

Relation to topological ends

In point-set topology, there is a concept of an end that is similar to, but not quite the same as, the concept of an end in graph theory, dating back much earlier to (Freudenthal 1931). If a topological space can be covered by a nested sequence of compact sets , then an end of the space is a sequence of components of the complements of the compact sets. This definition does not depend on the choice of the compact sets: the ends defined by one such choice may be placed in one-to-one correspondence with the ends defined by any other choice.

An infinite graph may be made into a topological space in two different but related ways:

- Replacing each vertex of the graph by a point and each edge of the graph by an open unit interval produces a Hausdorff space from the graph in which a set is defined to be open whenever each intersection of with an edge of the graph is an open subset of the unit interval.

- Replacing each vertex of the graph by a point and each edge of the graph by a point produces a non-Hausdorff space in which the open sets are the sets with the property that, if a vertex of belongs to , then so does every edge having as one of its endpoints.

In either case, every finite subgraph of corresponds to a compact subspace of the topological space, and every compact subspace corresponds to a finite subgraph together with, in the Hausdorff case, finitely many compact proper subsets of edges. Thus, a graph may be covered by a nested sequence of compact sets if and only if it is locally finite, having a finite number of edges at every vertex.

If a graph is connected and locally finite, then it has a compact cover in which the set is the set of vertices at distance at most from some arbitrarily chosen starting vertex. In this case any haven defines an end of the topological space in which . And conversely, if is an end of the topological space defined from , it defines a haven in which is the component containing , where is any number large enough that contains . Thus, for connected and locally finite graphs, the topological ends are in one-to-one correspondence with the graph-theoretic ends.[8]

For graphs that may not be locally finite, it is still possible to define a topological space from the graph and its ends. This space can be represented as a metric space if and only if the graph has a normal spanning tree, a rooted spanning tree such that each graph edge connects an ancestor-descendant pair. If a normal spanning tree exists, it has the same set of ends as the given graph: each end of the graph must contain exactly one infinite path in the tree.[9]

Special kinds of ends

Free ends

An end of a graph is defined to be a free end if there is a finite set of vertices with the property that separates from all other ends of the graph. (That is, in terms of havens, is disjoint from for every other end .) In a graph with finitely many ends, every end must be free. (Halin 1964) proves that, if has infinitely many ends, then either there exists an end that is not free, or there exists an infinite family of rays that share a common starting vertex and are otherwise disjoint from each other.

Thick ends

A thick end of a graph is an end that contains infinitely many pairwise-disjoint rays. Halin's grid theorem characterizes the graphs that contain thick ends: they are exactly the graphs that have a subdivision of the hexagonal tiling as a subgraph.[10]

Special kinds of graphs

Symmetric and almost-symmetric graphs

(Mohar 1991) defines a connected locally finite graph to be "almost symmetric" if there exist a vertex and a number such that, for every other vertex , there is an automorphism of the graph for which the image of is within distance of ; equivalently, a connected locally finite graph is almost symmetric if its automorphism group has finitely many orbits. As he shows, for every connected locally finite almost-symmetric graph, the number of ends is either at most two or uncountable; if it is uncountable, the ends have the topology of a Cantor set. Additionally, Mohar shows that the number of ends controls the Cheeger constant where ranges over all finite nonempty sets of vertices of the graph and where denotes the set of edges with one endpoint in . For almost-symmetric graphs with uncountably many ends, ; however, for almost-symmetric graphs with only two ends, .

Cayley graphs

Every group and a set of generators for the group determine a Cayley graph, a graph whose vertices are the group elements and the edges are pairs of elements where is one of the generators. In the case of a finitely generated group, the ends of the group are defined to be the ends of the Cayley graph for the finite set of generators; this definition is invariant under the choice of generators, in the sense that if two different finite set of generators are chosen, the ends of the two Cayley graphs are in one-to-one correspondence with each other.

For instance, every free group has a Cayley graph (for its free generators) that is a tree. The free group on one generator has a doubly infinite path as its Cayley graph, with two ends. Every other free group has infinitely many ends.

Every finitely generated infinite group has either 1, 2, or infinitely many ends, and the Stallings theorem about ends of groups provides a decomposition of groups with more than one end.[11] In particular:

- A finitely generated infinite group has 2 ends if and only if it has a cyclic subgroup of finite index.

- A finitely generated infinite group has infinitely many ends if and only if it is either a nontrivial free product with amalgamation or HNN-extension with finite amalgamation.

- All other finitely generated infinite groups have exactly one end.

Notes

- ↑ However, as (Krön Möller) point out, ends of graphs were already considered by (Freudenthal 1945).

- ↑ Halin (1964).

- ↑ E.g., this is the form of the equivalence relation used by (Diestel Kühn).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 The haven nomenclature, and the fact that two rays define the same haven if and only if they are equivalent, is due to (Robertson Seymour). (Diestel Kühn) proved that every haven comes from an end, completing the bijection between ends and havens, using a different nomenclature in which they called havens "directions".

- ↑ The proof by (Diestel Kühn) that every haven can be defined by a ray is nontrivial and involves two cases. If the set (where ranges over all finite sets of vertices) is infinite, then there exists a ray that passes through infinitely many vertices of , which necessarily determines . On the other hand, if is finite, then (Diestel Kühn) show that in this case there exists a sequence of finite sets that separate the end from all points whose distance from an arbitrarily chosen starting point in is . In this case, the haven is defined by any ray that is followed by a robber using the haven to escape police who land at set in round of the pursuit–evasion game.

- ↑ More precisely, in the original formulation of this result by (Halin 1964) in which ends are defined as equivalence classes of rays, every equivalence class of rays of contains a unique nonempty equivalence class of rays of the spanning forest. In terms of havens, there is a one-to-one correspondence of havens of order between and its spanning tree for which for every finite set and every corresponding pair of havens and .

- ↑ (Seymour Thomas); (Thomassen 1992); (Diestel 1992).

- ↑ (Diestel Kühn).

- ↑ Diestel (2006).

- ↑ (Halin 1965); (Diestel 2004).

- ↑ Stallings (1968, 1971).

References

- Diestel, Reinhard (1992), "The end structure of a graph: recent results and open problems", Discrete Mathematics 100 (1–3): 313–327, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(92)90650-5

- Diestel, Reinhard (2004), "A short proof of Halin's grid theorem", Abhandlungen aus dem Mathematischen Seminar der Universität Hamburg 74: 237–242, doi:10.1007/BF02941538

- Diestel, Reinhard (2006), "End spaces and spanning trees", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 96 (6): 846–854, doi:10.1016/j.jctb.2006.02.010

- Diestel, Reinhard (2003), "Graph-theoretical versus topological ends of graphs", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 87 (1): 197–206, doi:10.1016/S0095-8956(02)00034-5

- "Über die Enden topologischer Räume und Gruppen", Mathematische Zeitschrift 33: 692–713, 1931, doi:10.1007/BF01174375

- "Über die Enden diskreter Räume und Gruppen", Commentarii Mathematici Helvetici 17: 1–38, 1945, doi:10.1007/bf02566233

- "Über unendliche Wege in Graphen", Mathematische Annalen 157 (2): 125–137, 1964, doi:10.1007/bf01362670

- "Über die Maximalzahl fremder unendlicher Wege in Graphen", Mathematische Nachrichten 30 (1–2): 63–85, 1965, doi:10.1002/mana.19650300106

- Krön, Bernhard; Möller, Rögnvaldur G. (2008), "Metric ends, fibers and automorphisms of graphs", Mathematische Nachrichten 281 (1): 62–74, doi:10.1002/mana.200510587, http://homepage.univie.ac.at/bernhard.kroen/kroen_metric.pdf

- "Some relations between analytic and geometric properties of infinite graphs", Discrete Mathematics 95 (1–3): 193–219, 1991, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(91)90337-2, http://www.fmf.uni-lj.si/~mohar/Reprints/1991/BM91_Mohar_DM95_InfiniteGraphs.pdf

- "Excluding infinite minors", Discrete Mathematics 95 (1–3): 303–319, 1991, doi:10.1016/0012-365X(91)90343-Z

- "An end-faithful spanning tree counterexample", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 113 (4): 1163–1171, 1991, doi:10.2307/2048796

- "On torsion-free groups with infinitely many ends", Annals of Mathematics, Second Series 88 (2): 312–334, 1968, doi:10.2307/1970577

- Group theory and three-dimensional manifolds: A James K. Whittemore Lecture in Mathematics given at Yale University, 1969, Yale Mathematical Monographs, 4, New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1971

- "Infinite connected graphs with no end-preserving spanning trees", Journal of Combinatorial Theory, Series B 54 (2): 322–324, 1992, doi:10.1016/0095-8956(92)90059-7

|

KSF

KSF