Cartridge (firearms)

Topic: Engineering

From HandWiki - Reading time: 45 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 45 min

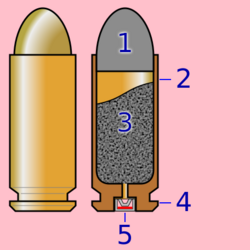

1. Bullet, as the projectile;

2. Cartridge case, which holds all parts together;

3. Propellant, for example, gunpowder or cordite;

4. Rim, which provides the extractor on the firearm a place to grip the casing to remove it from the chamber once fired;

5. Primer, which ignites the propellant

A cartridge,[1][2] also known as a round, is a type of pre-assembled firearm ammunition packaging a projectile (bullet, shot, or slug), a propellant substance (smokeless powder, black powder substitute, or black powder) and an ignition device (primer) within a metallic, paper, or plastic case that is precisely made to fit within the barrel chamber of a breechloading gun, for convenient transportation and handling during shooting.[3] Although in popular usage the term "bullet" is often used to refer to a complete cartridge, the correct usage only refers to the projectile.

Cartridges can be categorized by the type of their primers – a small charge of an impact- or electric-sensitive chemical mixture that is located: at the center of the case head (centerfire); inside the rim (rimfire); or formerly, inside the walls on the fold of the case base that is shaped like a cup (cupfire); in a sideways projection that is shaped like a pin (pinfire) or a lip (lipfire); or in a small nipple-like bulge at the case base (teat-fire). Only the centerfire and rimfire survive in mainstream usage today.

Military and commercial producers continue to pursue the goal of caseless ammunition. Some artillery ammunition uses the same cartridge concept as found in small arms. In other cases, the artillery shell is separate from the propellant charge.

A cartridge without a projectile is called a blank; one that is completely inert (contains no active primer and no propellant) is called a dummy; one that failed to ignite and shoot off the projectile is called a dud; and one that ignited but failed to sufficiently push the projectile out of the barrel is called a squib.

Design

Purpose

The cartridge was invented specifically for breechloading firearms. Prior to its invention, the projectiles and propellant were carried separately and had to be individually loaded via the muzzle into the gun barrel before firing, then have a separate ignitor compound (from a burning slow match, to a small charge of gunpowder in a flash pan, to a metallic percussion cap mounted on top of a "nipple" or cone), to serve as a source of activation energy to set off the shot. Such loading procedures often require adding paper/cloth wadding and ramming down repeatedly with a rod to optimize the gas seal, and are thus clumsy and inconvenient, severely restricting the practical rate of fire of the weapon, leaving the shooter vulnerable to the threat of close combat (particularly cavalry charges) as well as complicating the logistics of ammunition.

The primary purpose of using a cartridge is to offer a handy pre-assembled "all-in-one" package that is convenient to handle and transport, easily loaded into the breech (rear end) of the barrel, as well as preventing potential propellant loss, contamination or degradation from moisture and the elements. In modern self-loading firearms, the cartridge case also enables the action mechanism to use part of the propellant's energy (carried inside the cartridge itself) and cyclically load new rounds of ammunition to allow quick repeated firing.

To perform a firing, the round is first inserted into a "ready" position within the chamber aligned with the bore axis (i.e. "in battery"). While in the chamber, the cartridge case obturates all other directions except the bore to the front, reinforced by a breechblock or a locked bolt from behind, designating the forward direction as the path of least resistance. When the trigger is pulled, the sear disengages and releases the hammer/striker, causing the firing pin to impact the primer embedded in the base of the cartridge. The shock-sensitive chemical in the primer then creates a jet of sparks that travels into the case and ignites the main propellant charge within, causing the powders to deflagrate (but not detonate). This rapid exothermic combustion yields a mixture of highly energetic gases and generates a very high pressure inside the case, often fire-forming it against the chamber wall. When the pressure builds up sufficiently to overcome the fastening friction between the projectile (e.g. bullet) and the case neck, the projectile will detach from the case and, pushed by the expanding high-pressure gases behind it, move down the bore and out the muzzle at extremely high speed. After the bullet exits the barrel, the gases are released to the surroundings as ejectae in a loud blast, and the chamber pressure drops back down to ambient level. The case, which had been elastically expanded by high pressure, contracts slightly, which eases its removal from the chamber when pulled by the extractor. The spent cartridge, with its projectile and propellant gone but the case still containing a used-up primer, then gets ejected from the gun to clear room for a subsequent new round.

Components

A typical modern cartridge consists of four components: a case, a projectile, the propellant, and a primer.

Case

The main defining component of the cartridge is the case, which gives the cartridge its shape and serves as the integrating housing for other functional components—it acts as a container for the propellant powders and also serves as a protective shell against the elements; it attaches the projectile either at the front end of the cartridge (bullets for pistols, submachine guns, rifles, and machine guns) or inside of the cartridge (wadding/sabot containing either a quantity of shot (pellets) or an individual slug for shotguns), and align it with the barrel bore to the front; it holds the primer at the back end, which receives an impact from a firing pin and is responsible for igniting the main propellant charge inside the case.

While historically paper had been used in the earliest cartridges, almost all modern cartridges use metallic casing. The modern metallic case can either be a "bottleneck" one, whose frontal portion near the end opening (known as the "case neck") has a noticeably smaller diameter than the main part of the case ("case body"), with a noticeably angled slope ("case shoulder") in between; or a "straight-walled" one, where there is no narrowed neck and the whole case looks cylindrical. The case shape is meant to match exactly to the chamber of the gun that fires it, and the "neck", "shoulder", and "body" of a bottleneck cartridge have corresponding counterparts in the chamber known as the "chamber neck", "chamber shoulder", and "chamber body". Some cartridges, like the .470 Capstick, have what is known as a "ghost shoulder" which has a very slightly protruding shoulder, and can be viewed as a something between a bottleneck and straight-walled case. A ghost shoulder, rather than a continuous taper on the case wall, helps the cartridge to line up concentrically with the bore axis, contributing to accuracy. The front opening of the case neck, which receives and fastens the bullet via crimping, is known as the case mouth. The closed-off rear end of the case body, which holds the primer and technically is the case base, is ironically called the case head as it is the most prominent and frequently the widest part of the case. There is a circumferential flange at the case head called a rim, which provides a lip for the extractor to engage. Depending on whether and how the rim protrudes beyond the maximum case body diameter, the case can be classified as either "rimmed", "semi-rimmed", "rimless", "rebated", or "belted".

The shape of a bottleneck cartridge case (e.g. body diameter, shoulder slant angle and position, neck length) also affects the amount of attainable pressure inside the case, which in turn influences the accelerative capacity of the projectile. Wildcat cartridges are often made by reshaping the case of an existing cartridge. Straight-sided cartridges are less prone to rupturing than tapered cartridges, in particular with higher pressure propellant when used in blowback-operated firearms.

In addition to case shape, rifle cartridges can also be grouped according to the case dimensions, which in turn dictates the minimal receiver size and operating space (bolt travel) needed by the action, into either "mini-action", "short-action", "long-action" ("standard-action"), or "magnum" categories.

- Mini-action cartridges, are usually referring to intermediate rifle cartridges, typically with a cartridge overall length (COL) of 57 mm (2.25 in) or shorter, exemplified by the .223 Remington and 7.62×39mm;

- Short-action cartridges include all full-powered rifle cartridges with a COL between 57 and 71 mm (2.25 and 2.8 in), most commonly exemplified by the .308 Winchester;

- Long-action cartridges, also known as the "standard-action" cartridges, are traditional full-powered rifle cartridges with a COL between 71 and 85 mm (2.8 and 3.34 in), exemplified by the .30-06 Springfield;

- Magnum-action cartridges, are usually longer than the traditional full-powered rifle cartridges, with a COL between 85 and 91 mm (3.34 and 3.6 in), as well as some long-action cartridges with a case head larger than 13 mm (.50 in) diameter, exemplified by the .300 Winchester Magnum and 7mm Remington Magnum.[4]

The most popular material used to make cartridge cases is brass due to its good corrosion resistance. The head of a brass case can be work-hardened to withstand the high pressures, and allow for manipulation via extraction and ejection without rupturing. The neck and body portion of a brass case is easily annealed to make the case ductile enough to allow reshaping so that it can be handloaded many times, and fire forming can help accurize the shooting.

Steel casing is used in some plinking ammunition, as well as in some military ammunition (mainly from the former Soviet Union and China ).[citation needed] Steel is less expensive to make than brass, but it is far less corrosion-resistant and not feasible to reuse and reload. Military forces typically consider service small arms cartridge cases to be disposable, single-use devices. However, the mass of the cartridges can affect how much ammunition a soldier can carry, so the lighter steel cases do have a logistic advantage.[5] Conversely, steel is more susceptible to contamination and damage so all such cases are varnished or otherwise sealed against the elements. One downside caused by the increased strength of steel in the neck of these cases (compared to the annealed neck of a brass case) is that propellant gas can blow back past the neck and leak into the chamber. Constituents of these gases condense on the (relatively cold) chamber wall, and this solid propellant residue can make extraction of fired cases difficult. This is less of a problem for small arms of the former Warsaw Pact nations, which were designed with much looser chamber tolerances than NATO weapons.[citation needed]

Aluminum-cased cartridges are available commercially. These are generally not reloaded, as aluminum fatigues easily during firing and resizing. Some calibers also have non-standard primer sizes to discourage reloaders from attempting to reuse these cases.

This article is missing information about semi-combustible cases in 120×570mm NATO tank shells: the body is polymer, but the base stays. (March 2023) |

Plastic cases are commonly used in shotgun shells, and some manufacturers have now started offering polymer-cased centerfire rifle cartridges.

Projectile

As firearms are projectile weapons, the projectile is the effector component of the cartridge, and is actually responsible for reaching, impacting, and exerting damage onto a target. The word "projectile" is an umbrella term that describes any type of kinetic object launched into ballistic flight, but due to the ubiquity of rifled firearms shooting bullets, the term has become somewhat a technical synonym for bullets among handloaders. The projectile's motion in flight is known as its external ballistics, and its behavior upon impacting an object is known as its terminal ballistics.

A bullet can be made of virtually anything (see below), but lead is the traditional material of choice because of its high density, malleability, ductility, and low cost of production. However, at speeds greater than 300 m/s (980 ft/s), pure lead will melt more and deposit fouling in rifled bores at an ever-increasing rate. Alloying the lead with a small percentage of tin or antimony can reduce such fouling, but grows less effective as velocities are increased. A cup made of harder metal (e.g. copper), called a gas check, is often placed at the base of a lead bullet to decrease lead deposits by protecting the rear of the bullet against melting when fired at higher pressures, but this too does not work at higher velocities. A modern solution is to cover the bare lead in a protective powder coat, as seen in some rimfire ammunitions. Another solution is to encase a lead core within a thin exterior layer of harder metal (e.g. gilding metal, cupronickel, copper alloys or steel), known as a jacketing. In modern days, steel, bismuth, tungsten, and other exotic alloys are sometimes used to replace lead and prevent release of toxicity into the environment. In armor-piercing bullets, very hard and high-density materials such as hardened steel, tungsten, tungsten carbide, or even depleted uranium are used for the penetrator core.

Non-lethal projectiles with very limited penetrative and stopping powers are sometimes used in riot control or training situations, where killing or even wounding a target at all would be undesirable. Such projectiles are usually made from softer and lower-density materials, such as plastic or rubber. Wax bullets (such as those used in Simunition training) are occasionally used for force-on-force tactical trainings, and pistol dueling with wax bullets used to be a competitive Olympic sport prior to World War I.

For smoothbore weapons such as shotguns, small metallic balls known as shots are typically used, which is usually contained inside a semi-flexible, cup-like sabot called "wadding". When fired, the wadding is launched from the gun as a payload-carrying projectile, loosens and opens itself up after exiting the barrel, and then inertially releases the contained shots as a hail of sub-projectiles. Shotgun shots are usually made from bare lead, though copper/zinc–coated steel balls (such as those used by BB guns) can also be used. Lead pollution of wetlands has led to the BASC and other organizations campaigning for the phasing out of traditional lead shot.[6] There are also unconventional projectile fillings such as bundled flechettes, rubber balls, rock salt and magnesium shards, as well as non-lethal specialty projectiles such as rubber slugs and bean bag rounds. Solid projectiles (e.g. slugs, baton rounds, etc.) are also shot while contained within a wadding, as the wadding obturates the bore better and typically slides less frictionally within the barrel.

Propellant

The propellant is what actually fuels the main function of any firearm (i.e. shooting out the projectile). When a propellant deflagrates (subsonic combustion), the redox reaction breaks its molecular bonds and releases the chemical energy stored within. At the same time, the combustion yields significant amount of gaseous products, which is highly energetic due to the exothermic nature of the reaction. These combustion gases become highly pressurized when confined in a rigid space – such as the cartridge casing (reinforced by the chamber wall) occluded from the front by the projectile (bullet, or wadding containing shots/slug) and from behind by the primer (supported by the bolt/breechblock). When the pressure builds up high enough to overcome the crimp friction between the projectile and the case, the projectile separates from the case and gets propelled down the gun barrel by further expansion of the gases like a piston engine, receiving kinetic energy from the propellant gases and accelerating to a very high muzzle velocity within a short distance (i.e. the barrel length). The projectile motion driven by the propellant inside the gun is known as the internal ballistics.

The oldest gun propellant was black gunpowder, a low explosive made from a mixture of sulfur, carbon and potassium nitrate, invented in China during the 9th century as one of Four Great Inventions, and still remains in occasional use as a solid propellant (mostly for antique firearms and pyrotechnics). Modern firearm propellants however are smokeless powders based on nitrocellulose and nitroglycerin, first invented during the late 19th century as a cleaner and better-performing replacement for black powder. Modern smokeless powder may be corned into small spherical balls, or extruded into cylinders or strips with many cross-sectional shapes using solvents such as ether, which can be cut into short ("flakes") or long pieces ("cords").

The performance characteristics of a propellant are greatly influenced by its grain size and shape, because the specific surface area influences the burn rate, which in turn influences the rate of pressurization. Short-barrel firearms such as handguns necessitate faster-burning propellants to obtain sufficient muzzle energy, while long guns typically use slower-burning propellants.

Due to the relatively short distance a gun barrel can offer, the sealed acceleration time is very limited and only a small proportion of the total energy generated by the propellant combustion will get transferred to the projectile. The residual energy in the propellant gases gets dissipated to the surrounding in the form of heat, vibration/deformation, light (in the form of muzzle flash) and a prominent muzzle blast (which is responsible for the loud sound/concussive shock perceivable to bystanders and most of the recoil felt by the shooter, as well as potentially deflecting the bullet), or as unusable kinetic energy transferred to other ejecta byproducts (e.g. unburnt powders, dislodged foulings).

Primer

Because the main propellant charge are located deep inside the gun barrel and thus impractical to be directly lighted from the outside, an intermediate is needed to relay the ignition. In the earliest black powder muzzleloaders, a fuse was used to direct a small flame through a touch hole into the barrel, which was slow and subjected to disturbance from environmental conditions. The next evolution was to have a small separate charge of finer gunpowder poured into a flash pan, where it could start a "priming" ignition by an external source such as a slow match (matchlock), or a pyrite (wheellock) or a flint striking a steel frizzen (snaplock and flintlock) to create sparks. When the primer powder starts combusting, the flame is transferred through an internal touch hole called a flash hole to provide activation energy for the main powder charge in the barrel. The disadvantage was that the flash pan could still be exposed to the outside, making it difficult (or even impossible) to fire the gun in rainy or humid conditions as wet gunpowder burns poorly.

After Edward Charles Howard discovered fulminates in 1800[7][8] and the patent by Reverend Alexander John Forsyth expired in 1807,[9] Joseph Manton invented the precursor percussion cap in 1814,[10] which was further developed in 1822 by the English-born American artist Joshua Shaw,[11] and caplock fowling pieces appeared in Regency era England. These guns used a spring-loaded hammer to strike a percussion cap placed over a conical nipple, which served as both an "anvil" against the hammer strike and a transfer port for the sparks created by impactfully crushing the cap, and was easier and quicker to load, more resilient to weather conditions, and more reliable than the preceding flintlocks.[9]

Modern primers are basically improved percussion caps with shock-sensitive chemicals (e.g. lead styphnate) enclosed in a small button-shaped capsule. In the early paper cartridges, invented not long after the percussion cap, the primer was located deep inside the cartridge just behind the bullet, requiring a very thin and elongated firing pin to pierce the paper casing. Such guns were known as needle guns, the most famous of which was decisive in the Prussian victory over the Austrians at Königgrätz in 1866. After the metallic cartridge was invented, the primer was relocated backward to the base of the case, either at the center of the case head (centerfire), inside the rim (rimfire), inside a cup-like concavity of the case base (cupfire), in a pin-shaped sideways projection (pinfire), in a lip-like flange (lipfire), or in a small nipple-like bulge at the case base (teat-fire). Today, only the centerfire and rimfire have survived the test of time as the mainstream primer designs, while the pinfire also still exists but only in rare novelty miniature guns and a few very small blank cartridges designed as noisemakers.

In rimfire ammunitions, the primer compound is moulded integrally into the interior of the protruding case rim, which is crushed between the firing pin and the edge of the barrel breech (serving as the "anvil"). These ammunitions are thus not reloadable, and are usually on the lower end of the power spectrum, although due to the low manufacturing cost some of them (e.g. .22 Long Rifle) are among the most popular and prolific ammunitions currently being used.

Centerfire primers are a separately manufactured component, seated into a central recess at the case base known as the primer pocket, and have two types: Berdan and Boxer. Berdan primers, patent by American inventor Hiram Berdan in 1866, are a simple capsule, and the corresponding case has two small flash holes with a bulged bar in between, which serves as the "anvil" for the primer. Boxer primers, patented by Royal Artillery colonel Edward Mounier Boxer also in 1866, are more complex and have an internal tripedal "anvil" built into the primer itself, and the corresponding case has only a single large central flash hole. Commercially, Boxer primers dominate the handloader market due to the ease of depriming and the ability to transfer sparks more efficiently.

Due to their small size and charge load, primers lack the power to shoot out the projectile by themselves, but can still put out enough energy to separate the bullet from the casing and push it partway into the barrel – a dangerous condition called a squib load. Firing a fresh cartridge behind a squib load obstructing the barrel will generate dangerously high pressure, leading to a catastrophic failure and potentially causing severe injuries when the gun blows apart in the shooter's hands. Actor Brandon Lee's infamous accidental death in 1993 was believed to be caused by an undetected squib that was dislodged and shot out by a blank.

Manufacturing

Beginning in the 1860s, early metallic cartridges (e. g. for the Montigny mitrailleuse[13] or the Snider–Enfield rifle[14]) were produced similarly to the paper cartridges, with sides made from thick paper, but with copper (later brass) foil supporting the base of the cartridge and some more details in it holding the primer. In the 1870s, brass foil covered all of the cartridge, and the technology to make solid cases, in which the metallic cartridges described below were developed, but before the 1880s, it was far too expensive and time consuming for mass production[15] and the metallurgy was not yet perfected.[16]

To manufacture cases for cartridges, a sheet of brass is punched into disks. These disks go through a series of drawing dies. The disks are annealed and washed before moving to the next series of dies. The brass needs to be annealed to remove the work-hardening in the material and make the brass malleable again ready for the next series of dies.[12]

Manufacturing bullet jackets is similar to making brass cases: there is a series of drawing steps with annealing and washing.[12]

Specifications

Critical cartridge specifications include neck size, bullet weight and caliber, maximum pressure, headspace, overall length, case body diameter and taper, shoulder design, rim type, etc. Generally, every characteristic of a specific cartridge type is tightly controlled and few types are interchangeable in any way. Exceptions do exist but generally, these are only where a shorter cylindrical rimmed cartridge can be used in a longer chamber, (e.g., .22 Short in .22 Long Rifle chamber, .32 H&R Magnum in .327 Federal Magnum chamber, and .38 Special in a .357 Magnum chamber). Centerfire primer type (Boxer or Berdan, see below) is interchangeable, although not in the same case. Deviation in any of these specifications can result in firearm damage and, in some instances, injury or death. Similarly, the use of the wrong type of cartridge in any given gun can damage the gun, or cause bodily injury.

Cartridge specifications are determined by several standards organizations, including SAAMI in the United States, and C.I.P. in many European states. NATO also performs its own tests for military cartridges for its member nations; due to differences in testing methods, NATO cartridges (headstamped with the NATO cross) may present an unsafe combination when loaded into a weapon chambered for a cartridge certified by one of the other testing bodies.[17]

Bullet diameter is measured either as a fraction of an inch (usually in 1/100 or in 1/1000) or in millimeters. Cartridge case length can also be designated in inches or millimeters.

History

(1) Colt Army 1860 .44 paper cartridge, Civil War

(2) Colt Thuer-Conversion .44 revolver cartridge, patented in 1868

(3) .44 Henry rim fire cartridge flat

(4) .44 Henry rim fire cartridge pointed

(5) Frankford Arsenal .45 Colt cartridge, Benét ignition

(6) Frankford Arsenal .45 Colt-Schofield cartridge, Benét ignition

Paper cartridges have been in use for centuries, with a number of sources dating their usage as far back as the late 14th and early 15th centuries. Historians note their use by soldiers of Christian I, Elector of Saxony and his son in the late 16th century,[18][19] while the Dresden Armoury has evidence dating their use to 1591.[20][18] Capo Bianco wrote in 1597 that paper cartridges had long been in use by Neapolitan soldiers. Their use became widespread by the 17th century.[18] The 1586 round consisted of a charge of powder and a bullet in a paper cartridge. Thick paper is still known as "cartridge paper" from its use in these cartridges.[21] Another source states the cartridge appeared in 1590.[22] King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden had his troops use cartridges in the 1600s.[23] The paper formed a cylinder with twisted ends; the ball was at one end, and the measured powder filled the rest.[24]

This cartridge was used with muzzle-loading military firearms, probably more often than for sporting shooting, the base of the cartridge being ripped or bitten off by the soldier, the powder poured into the barrel, and the paper and bullet rammed down the barrel.[25] In the Civil War era cartridge, the paper was supposed to be discarded, but soldiers often used it as a wad.[26] To ignite the charge an additional step was required where a finer-grained powder called priming powder was poured into the pan of the gun to be ignited by the firing mechanism.

The evolving nature of warfare required a firearm that could load and fire more rapidly, resulting in the flintlock musket (and later the Baker rifle), in which the pan was covered by furrowed steel. This was struck by the flint and fired the gun. In the course of loading, a pinch of powder from the cartridge would be placed into the pan as priming, before the rest of the cartridge was rammed down the barrel, providing charge and wadding.[27]

Later developments rendered this method of priming unnecessary, as, in loading, a portion of the charge of powder passed from the barrel through the vent into the pan, where it was held by the cover and hammer. [citation needed]

The next important advance in the method of ignition was the introduction of the copper percussion cap. This was only generally applied to the British military musket (the Brown Bess) in 1842, a quarter of a century after the invention of percussion powder and after an elaborate government test at Woolwich in 1834. The invention that made the percussion cap possible was patented by the Rev. A. J. Forsyth in 1807 and consisted of priming with a fulminating powder made of potassium chlorate, sulfur, and charcoal, which ignited by concussion. This invention was gradually developed, and used, first in a steel cap, and then in a copper cap, by various gunmakers and private individuals before coming into general military use nearly thirty years later.[citation needed]

The alteration of the military flint-lock to the percussion musket was easily accomplished by replacing the powder pan with a perforated nipple and by replacing the cock or hammer that held the flint with a smaller hammer that had a hollow to fit on the nipple when released by the trigger. The shooter placed a percussion cap (now made of three parts of potassium chlorate, two of fulminate of mercury and powdered glass) on the nipple. The detonating cap thus invented and adopted brought about the invention of the modern cartridge case, and rendered possible the general adoption of the breech-loading principle for all varieties of rifles, shotguns, and pistols. This greatly streamlined the reloading procedure and paved the way for semi- and full-automatic firearms.[citation needed]

However, this big leap forward came at a price: it introduced an extra component into each round – the cartridge case – which had to be removed before the gun could be reloaded. While a flintlock, for example, is immediately ready to reload once it has been fired, adopting brass cartridge cases brought in the problems of extraction and ejection. The mechanism of a modern gun must not only load and fire the piece but also provide a method of removing the spent case, which might require just as many added moving parts. Many malfunctions occur during this process, either through a failure to extract a case properly from the chamber or by allowing the extracted case to jam the action. Nineteenth-century inventors were reluctant to accept this added complication and experimented with a variety of caseless or self-consuming cartridges before finally accepting that the advantages of brass cases far outweighed this one drawback.[28]

Integrated cartridges

The first integrated cartridge was developed in Paris in 1808 by the Swiss gunsmith Jean Samuel Pauly in association with French gunsmith François Prélat. Pauly created the first fully self-contained cartridges:[29] the cartridges incorporated a copper base with integrated mercury fulminate primer powder (the major innovation of Pauly), a round bullet and either brass or paper casing.[30][31] The cartridge was loaded through the breech and fired with a needle. The needle-activated centerfire breech-loading gun would become a major feature of firearms thereafter.[32] Pauly made an improved version, protected by a patent, on 29 September 1812.[29]

Probably no invention connected with firearms has wrought such changes in the principle of gun construction as those effected by the "expansive cartridge case". This invention has completely revolutionized the art of gun making, has been successfully applied to all descriptions of firearms and has produced a new and important industry: that of cartridge manufacture. Its essential feature is preventing gas from escaping the breech when the gun is fired, by means of an expansive cartridge case containing its own means of ignition. Previous to this invention shotguns and sporting rifles were loaded by means of powder flasks and shot bags or flasks, bullets, wads, and copper caps, all carried separately. One of the earliest efficient modern cartridge cases was the pinfire cartridge, developed by French gunsmith Casimir Lefaucheux in 1836.[33] It consisted of a thin weak shell made of brass and paper that expanded from the force of the explosion. This fit perfectly in the barrel and thus formed an efficient gas check. A small percussion cap was placed in the middle of the base of the cartridge and was ignited by means of a brass pin projecting from the side and struck by the hammer. This pin also afforded the means of extracting the cartridge case. This cartridge was introduced in England by Lang, of Cockspur Street, London, about 1845.

In the American Civil War (1861–1865) a breech-loading rifle, the Sharps, was introduced and produced in large numbers. It could be loaded with either a ball or a paper cartridge. After that war, many were converted to the use of metal cartridges. The development by Smith & Wesson (among many others) of revolver handguns that used metal cartridges helped establish cartridge firearms as the standard in the United States by the late 1860s and early 1870s, although many continue to use percussion revolvers well after that.[34]

Modern metallic cartridges

Most of the early all-metallic cartridges were of the pinfire and rimfire types.

The first centerfire metallic cartridge was invented by Jean Samuel Pauly in the first decades of the 19th century. However, although it was the first cartridge to use a form of obturation, a feature integral to a successful breech-loading cartridge, Pauly died before it was converted to percussion cap ignition.

Frenchman Louis-Nicolas Flobert invented the first rimfire metallic cartridge in 1845. His cartridge consisted of a percussion cap with a bullet attached to the top.[35][36] Flobert then made what he called "parlor guns" for this cartridge, as these rifles and pistols were designed to be shot in indoor shooting parlors in large homes.[37][38] These 6mm Flobert cartridges do not contain any powder. The only propellant substance contained in the cartridge is the percussion cap.[39] In English-speaking countries, the 6mm Flobert cartridge corresponds to .22 BB Cap and .22 CB Cap ammunition. These cartridges have a relatively low muzzle velocity of around 700 ft/s (210 m/s).

French gunsmith Benjamin Houllier improved the Lefaucheux pinfire cardboard cartridge and patented in Paris in 1846, the first fully metallic pinfire cartridge containing powder in a metallic cartridge.[33][40] He also included in his patent claims rim and centerfire primed cartridges using brass or copper casings.[30] Houllier commercialised his weapons in association with the gunsmiths Blanchard or Charles Robert.[41][42]

In the United States, in 1857, the Flobert cartridge inspired the .22 Short, specially conceived for the first American revolver using rimfire cartridges, the Smith & Wesson Model 1. A year before, in 1856, the LeMat revolver was the first American breech-loading firearm, but it used pinfire cartridges, not rimfire. Formerly, an employee of the Colt's Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company, Rollin White, had been the first in America to conceive the idea of having the revolver cylinder bored through to accept metallic cartridges (circa 1852), with the first in the world to use bored-through cylinders probably having been Lefaucheux in 1845, who invented a pepperbox-revolver loaded from the rear using bored-through cylinders.[43] Another possible claimant for the bored-through cylinder is a Frenchman by the name of Perrin, who allegedly produced in 1839 a pepperbox revolver with a bored-through cylinder to order. Other possible claimants include Devisme of France in 1834 or 1842 who claimed to have produced a breech-loading revolver in that period though his claim was later judged as lacking in evidence by French courts and Hertog & Devos and Malherbe & Rissack of Belgium who both filed patents for breech-loading revolvers in 1853.[44] However, Samuel Colt refused this innovation. White left Colt, went to Smith & Wesson to rent a license for his patent, and this is how the S&W Model 1 saw the light of day in 1857. The patent didn't definitely expire until 1870, allowing Smith & Wesson competitors to design and commercialize their own revolving breech-loaders using metallic cartridges. Famous models of that time are the Colt Open Top (1871–1872) and Single Action Army "Peacemaker" (1873). But in rifles, the lever-action mechanism patents were not obstructed by Rollin White's patent infringement because White only held a patent concerning drilled cylinders and revolving mechanisms. Thus, larger caliber rimfire cartridges were soon introduced after 1857, when the Smith & Wesson .22 Short ammunition was introduced for the first time. Some of these rifle cartridges were used in the American Civil War, including the .44 Henry and 56-56 Spencer (both in 1860). However, the large rimfire cartridges were soon replaced by centerfire cartridges, which could safely handle higher pressures.[45][46]

In 1867, the British war office adopted the Eley–Boxer metallic centerfire cartridge case in the Pattern 1853 Enfield rifles, which were converted to Snider-Enfield breech-loaders on the Snider principle. This consisted of a block opening on a hinge, thus forming a false breech against which the cartridge rested. The priming cap was in the base of the cartridge and was discharged by a striker passing through the breech block. Other European powers adopted breech-loading military rifles from 1866 to 1868, with paper instead of metallic cartridge cases. The original Eley-Boxer cartridge case was made of thin-coiled brass—occasionally these cartridges could break apart and jam the breech with the unwound remains of the case upon firing. Later the solid-drawn, centerfire cartridge case, made of one entire solid piece of tough hard metal, an alloy of copper, with a solid head of thicker metal, has been generally substituted.[citation needed]

Centerfire cartridges with solid-drawn metallic cases containing their own means of ignition are almost universally used in all modern varieties of military and sporting rifles and pistols.[citation needed]

Around 1870, machined tolerances had improved to the point that the cartridge case was no longer necessary to seal a firing chamber. Precision-faced bolts would seal as well, and could be economically manufactured.[citation needed] However, normal wear and tear proved this system to be generally infeasible.

Factory vs. handloading

Nomenclature

The name of any given cartridge does not necessarily reflect any cartridge or gun dimension. The name is merely the standardized and accepted moniker. SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute) and the European counterpart (CIP) and members of those organizations specify correct cartridge names.

It is incomplete to refer to a cartridge as a certain "caliber" (e.g., "30-06 caliber"), as the word caliber only describes the bullet diameter. The correct full name for this round is .30–'06 Springfield. The "-'06" means it was introduced in 1906. In sporting arms, the only consistent definition of "caliber" is bore diameter, and dozens of unique .30-caliber round types exist.

There is considerable variation in cartridge nomenclature. Names sometimes reflect various characteristics of the cartridge. For example, the .308 Winchester uses a bullet of 308/1000-inch diameter and was standardized by Winchester. Conversely, cartridge names often reflect nothing related to the cartridge in any obvious way. For example, the .218 Bee uses a bullet of 224/1000-inch diameter, fired through a .22-in bore, etc. The 218 and Bee portions of this cartridge name reflect nothing other than the desires of those who standardized that cartridge. Many similar examples exist, for example: .219 Zipper, .221 Fireball, .222 Remington, .256 Winchester, .280 Remington, .307 Winchester, .356 Winchester.

Where two numbers are used in a cartridge name, the second number may reflect a variety of things. Frequently the first number reflects bore diameter (inches or millimeters). The second number reflects case length (in inches or mm). For example, the 7.62×51mm NATO refers to a bore diameter of 7.62 mm and has an overall case length of 51 mm, with a total length of 71.1 mm. The commercial version is the .308 Winchester.

In older black powder cartridges, the second number typically refers to powder charge, in grains. For example, the .50-90 Sharps has a .50-inch bore and used a nominal charge of 90.0 grains (5.83 g) of black powder.

Many such cartridges were designated by a three-number system (e.g., 45–120–31⁄4 Sharps: 45-caliber bore, 120 grains of (black) powder, 31⁄4-inch long case). Other times, a similar three-number system indicated bore (caliber), charge (grains), and bullet weight (grains). The 45-70-500 Government is an example.

Often, the name reflects the company or individual who standardized it, such as the .30 Newton, or some characteristic important to that person.

The .38 Special actually has a nominal bullet diameter of 0.3570 inches (9.07 mm) (jacketed) or 0.3580 inches (9.09 mm) (lead) while the case has a nominal diameter of 0.3800 inches (9.65 mm), hence the name. This is historically logical: the hole drilled through the chambers of .36-caliber cap-and-ball revolvers when converting those to work with cartridges was 0.3800 inches (9.65 mm), and the cartridge made to work in those revolvers was logically named the .38 Colt. The original cartridges used a heeled bullet like a .22 rimfire where the bullet was the same diameter as the case. Early Colt Army .38s have a bore diameter that will allow a .357" diameter bullet to slide through the barrel. The cylinder is bored straight through with no step. Later versions used an inside the case lubricated bullet of .357" diameter instead of the original .38" with a reduction in bore diameter. The difference in .38 Special bullet diameter and case diameter reflects the thickness of the case mouth (approximately 11/1000-inch per side). The .357 Magnum evolved from the .38 Special. The .357 was named to reflect bullet diameter (in thousandths inch), not case diameter. "Magnum" was used to indicate its longer case and higher operating pressure.

Classification

Cartridges are classified by some major characteristics. One classification is the location of the primer. Early cartridges began with the pinfire, then the rimfire, and finally the centerfire.

Another classification describes how cartridges are located in the chamber (headspace). Rimmed cartridges are located with the rim near the cartridge head; the rim is also used to extract the cartridge from the chamber. Examples are the .22 long rifle and .303 British. In a rimless cartridge, the cartridge head diameter is about the same as or smaller than the body diameter. The head will have a groove so the cartridge can be extracted from the chamber. Locating the cartridge in the chamber is accomplished by other means. Some rimless cartridges are necked down, and they are positioned by the cartridge's shoulder. An example is the .30-06 Springfield. Pistol cartridges may be located by the end of the brass case. An example is the .45 ACP. A belted cartridge has a larger diameter band of thick metal near the head of the cartridge. An example is the .300 Weatherby Magnum. An extreme version of the rimless cartridge is the rebated case; guns employing advanced primer ignition need such a case because the case moves during firing (i.e., it is not located at a fixed position). An example is the 20mm×110RB.

Centerfire

A centerfire cartridge has a centrally located primer held within a recess in the case head. Most centerfire brass cases used worldwide for sporting ammunition use Boxer primers. It is easy to remove and replace Boxer primers using standard reloading tools, facilitating reuse.

Some European- and Asian-manufactured military and sporting ammunition uses Berdan primers. Removing the spent primer from (decapping) these cases requires the use of a special tool because the primer anvil (on which the primer compound is crushed) is an integral part of the case and the case, therefore, does not have a central hole through which a decapping tool can push the primer out from the inside, as is done with Boxer primers. In Berdan cases, the flash holes are located to the sides of the anvil. With the right tool and components, reloading Berdan-primed cases is perfectly feasible. However, Berdan primers are not readily available in the U.S.

Rimfire

Rimfire priming was a popular solution before centerfire priming was perfected. In a rimfire case, centrifugal force pushes a liquid priming compound into the internal recess of the folded rim as the manufacturer spins the case at a high rate and heats the spinning case to dry the priming compound mixture in place within the hollow cavity formed within the rim fold at the perimeter of the case interior.

In the mid to late 19th century, many rimfire cartridge designs existed. Today only a few, mostly for use in small-caliber guns, remain in general and widespread use. These include the .17 Mach II, .17 Hornady Magnum Rimfire (HMR), 5mm Remington Magnum (Rem Mag), .22 (BB, CB, Short, Long, Long Rifle), and .22 Winchester Magnum Rimfire (WMR).

Compared to modern centerfire cases used in the strongest types of modern guns, existing rimfire cartridge designs use loads that generate relatively low pressure because of limitations of feasible gun design – the rim has little or no lateral support from the gun. Such support would require very close tolerances in the design of the chamber, bolt, and firing pin. Because that is not cost-effective, it is necessary to keep rimfire load pressure low enough so that the stress generated by chamber pressure that would push the case rim outward cannot expand the rim significantly. Also, the wall of the folded rim must be thin and ductile enough to easily deform, as necessary to allow the blow from the firing pin to crush and thereby ignite the primer compound, and it must do so without rupturing, If it is too thick, it will be too resistant to deformation. If it is too hard, it will crack rather than deform. These two limitations – that the rim is self-supporting laterally and that the rim is thin and ductile enough to easily crush in response to the firing pin impact – limit rimfire pressures.[46]

Modern centerfire cartridges are often loaded to about 65,000 psi (450,000 kPa) maximum chamber pressure. Conversely, no commercialized rimfire has ever been loaded above about 40,000 psi (280,000 kPa) maximum chamber pressure. However, with careful gun design and production, no fundamental reason exists that higher pressures could not be used. Despite the relative pressure disadvantage, modern rimfire magnums in .17-caliber/4.5mm, .20-caliber/5mm, and .22-caliber/5.6mm can generate muzzle energies comparable to smaller centerfire cartridges.[citation needed]

Today, .22 LR (Long Rifle) accounts for the vast majority of all rimfire ammunition used. Standard .22 LR rounds use an essentially pure lead bullet plated with a typical 95% copper, 5% zinc combination. These are offered in supersonic and subsonic types, as well as target, plinking, and hunting versions. These cartridges are usually coated with hard wax for fouling control.

The .22 LR and related rimfire .22 cartridges use a heeled bullet, where the external diameter of the case is the same as the diameter of the forward portion of the bullet and where the rearward portion of the bullet, which extends into the case, is necessarily smaller in diameter than the main body of the bullet.

Semi-automatic vs. revolver cartridges

Most revolver cartridges are rimmed at the base of the case, which seats against the edge of cylinder chamber to provide headspace control (to keep the cartridge from moving too far forward into the chamber) and to facilitate easy extraction.

Nearly every centerfire semi-automatic pistol cartridge is "rimless", where the rim is of the same diameter as the case body but separated by a circumferential groove in between, into which the extractor engages the rim by hooking. A "semi-rimmed" cartridge is essentially a rimless one but the rim diameter is slightly larger than the case body, and a "rebated rimless" cartridge is one with the rim smaller in diameter. All such cartridges' headspace on the case mouth (although some, such as .38 Super, at one time seated on the rim, this was changed for accuracy reasons), which prevents the round from entering too far into the chamber. Some cartridges have a rim that is significantly smaller than the case body diameter. These are known as rebated-rim designs and almost always allow a handgun to fire multiple caliber cartridges with only a barrel and magazine change.

-

Rimless .380 ACP semi-automatic cartridge

-

Rimmed .38 special revolver cartridge

Projectile designs

- A shotgun shell loaded with multiple metallic "shot", which are small, generally spherical projectiles.

- Shotgun slug: A single solid projectile designed to be fired from a shotgun.

- Baton round: a generally non-lethal projectile fired from a riot gun.

- Bullets

- Armor-piercing (AP): A hard bullet made from steel or tungsten alloys in a pointed shape typically covered by a thin layer of lead and or a copper or brass jacket. The lead and jacket are intended to prevent barrel wear from the hard-core materials. AP bullets are sometimes less effective on unarmored targets than FMJ bullets are. This has to do with the reduced tendency of AP projectiles to yaw (turn sideways after impact).

- Full metal jacket (FMJ): Made with a lead core surrounded by a full covering of brass, copper, or mild steel. These usually offer very little deformation or terminal performance expansion, but will occasionally yaw (turn sideways). Despite the name, an FMJ bullet typically has an exposed lead base, which is not visible in an intact cartridge.

- Glaser safety slug: Copper jackets filled with bird shot and covered by a crimped polymer endcap. Upon impact with flesh, the projectile is supposed to fragment, with the birdshot spreading like a miniature shotgun pattern.

- Jacketed hollow point (JHP): Soon after the invention of the JSP, Woolwich Arsenal in Great Britain experimented with this design even further by forming a hole or cavity in the nose of the bullet while keeping most of the exterior profile intact. These bullets could theoretically deform even faster and expand to a larger diameter than the JSP. In personal defense use, concerns have arisen over whether clothing, especially heavy materials like denim, can clog the cavity of JHP bullets and cause expansion failures.

- Jacketed soft point (JSP): In the late 19th century, the Indian Army at Dum-Dum Arsenal, near Kolkata, developed a variation of the FMJ design where the jacket did not cover the nose of the bullet. The soft lead nose was found to expand in the flesh while the remaining jacket still prevented lead fouling in the barrel. The JSP roughly splits the difference between FMJ and JHP. It gives more penetration than JHP but has better terminal ballistic characteristics than the FMJ.

- Round nose lead (RNL): An unjacketed lead bullet. Although largely supplanted by jacketed ammunition, this is still common for older revolver cartridges. Some hunters prefer roundnose ammunition for hunting in brush because they erroneously believe that such a bullet deflects less than sharp-nosed spitzer bullets, regardless of the fact that this belief has been repeatedly proven not to be true. Refer to American Rifleman magazine.

- Flat nose lead (FNL): Similar to round nose lead, with a flattened nose. Common in cowboy action shooting and plinking ammunition loads.

- Total metal jacket (TMJ): Featured in some Speer cartridges, the TMJ bullet has a lead core completely and seamlessly enclosed in brass, copper or other jacket metal, including the base. According to Speer's literature, this prevents hot propellant gases from vaporizing lead from the base of the bullet, reducing lead emissions. Sellier & Bellot produce a similar version that they call TFMJ, with a separate end cap of jacket material.

- Wadcutter (WC): Similar to the FNL, but completely cylindrical, in some instances with a slight concavity in the nose. This bullet derives its name from its popularity for target shooting, because the form factor cuts neat holes in paper targets, making scoring easier and more accurate and because it typically cuts a larger hole than a round nose bullet, a hit centered at the same spot can touch the next smaller ring and therefore score higher.

- Semi-wadcutter (SWC) identical to the WC with a smaller diameter flap pointed conical or radiused nose added. Has the same advantages for target shooters but is easier to load into the gun and works more reliably in semi-automatic guns. This design is also superior for some hunting applications.

- Truncated cone: Also known as round nose flat point, etc. Descriptive of typical modern commercial cast bullet designs.

The Hague Convention of 1899 bans the use of expanding projectiles against the military forces of other nations. Some countries accept this as a blanket ban against the use of expanding projectiles against anyone, while others[note 1] use JSP and HP against non-military forces such as terrorists and criminals.[47]

Common cartridges

Ammunition types are listed numerically.

- 22 Long Rifle (22 LR): A round that is often used for target shooting and the hunting of small game such as squirrels. Because of the small size of this round, the smallest self-defense handguns chambered in 22 rimfire (though less effective than most centerfire handguns cartridges) can be concealed in situations where a handgun chambered for a centerfire cartridge could not. The 22 LR is the most commonly fired sporting arms cartridge, primarily because, when compared to any centerfire ammunition, 22 LR ammunition is much less expensive and because recoil generated by the light 22 bullet at modest velocity is very mild.

- .22-250 Remington: A very popular round for medium to long range small game and varmint hunting, pest control, and target shooting. The 22–250 is one of the most popular rounds for fox hunting and other pest control in Western Europe due to its flat trajectory and very good accuracy on rabbit to fox-sized pests.

- .300 Winchester Magnum: One of the most popular big game hunting rounds of all time. Also, as a long-range sniping round, it is favored by US Navy SEALs and the German Bundeswehr. While not in the same class as the 338 Lapua, it has roughly the same power as 7 mm Remington Magnum, and easily exceeds the performance of 7.62×51mm NATO.

- 30-06 Springfield (7.62×63mm): The standard US Army rifle round for the first half of the 20th century. It is a full-power rifle round suitable for hunting most North American game and most big game worldwide.[48]

- .303 British: the standard British Empire military rifle cartridge from 1888 to 1954.[49]

- .308 Winchester: the commercial name of a centerfire cartridge based on the military 7.62×51mm NATO round. Two years prior to the NATO adoption of the 7.62×51mm NATO T65 in 1954, Winchester (a subsidiary of the Olin Corporation) branded the round and introduced it to the commercial hunting market as the 308 Winchester. The Winchester Model 70 and Model 88 rifles were subsequently chambered for this round. Since then, the 308 Winchester has become the most popular short-action big-game hunting round worldwide. It is also commonly used for civilian and military target events, military sniping and police sharpshooting.

- .357 Magnum: Using a lengthened version of the .38 Special case loaded to about twice the maximum chamber pressure as the 38 Spc., the 357 Magnum was rapidly accepted by hunters and law enforcement. At the time of its introduction, 357 Magnum bullets were claimed to easily pierce the body panels of automobiles and crack engine blocks (to eventually disable the vehicle).[50]

- .375 Holland & Holland Magnum: designed for hunting African big game in the early 20th century and legislated as the minimum caliber for African hunters during the mid-20th century[51]

- .40 S&W: A shorter-cased version of the 10mm Auto.

- .44 Magnum: A high-powered pistol round designed primarily for hunting.

- .45 ACP: The standard US pistol round for about one century. Typical 45 ACP loads are subsonic.[52]

- .45 Colt: a more powerful 45-caliber round using a longer cartridge. The 45 Colt was designed for the Colt Single Action Army, circa 1873. Other 45-caliber single-action revolvers also use this round.

- .45-70 Government: Adopted by the US Army in 1873 as their standard service rifle cartridge. Most commercial loadings of this cartridge are constrained by the possibility that someone might attempt to fire a modern loading in a vintage 1873 rifle or replica. However, current production rifles from Marlin, Ruger, and Browning can accept loads that generate nearly twice the pressure generated by the original black powder cartridges.

- .50 BMG (12.7×99mm NATO): Originally designed to destroy aircraft in the First World War,[53] this round still serves an anti-materiel round against light armor. It is used in heavy machine guns and high-powered sniper rifles. Such rifles can be used, amongst other things, for destroying military matériel such as sensitive parts of grounded aircraft and armored transports. Civilian shooters use these for long-distance target shooting.

- 5.45×39mm Soviet: The Soviet response to the 5.56×45mm NATO round.

- 5.56×45mm NATO: Adopted by the US military in the 1960s, it later became the NATO standard rifle round in the early 80s, displacing the 7.62×51mm. Remington later adopted this military round as the .223 Remington, a very popular round for varminting and small game hunting.

- 7×64mm: One of the most popular long range varmint and medium- to big-game hunting rounds in Europe, especially in the countries such as France and (formerly) Belgium where the possession of firearms chambered for a (former) military round is forbidden or is more heavily restricted. This round is offered by European rifle makers in both bolt-action rifles and a rimmed version, the 7×65mmR is chambered in double and combination rifles. Another reason for its popularity is its flat trajectory, very good penetration and high versatility, depending on what bullet and load are used. Combined with a large choice of different 7 mm bullets available the 7×64mm is used on everything from fox and geese to red deer, Scandinavian moose and European brown bear equivalent to the North American black bear. The 7×64mm essentially duplicates the performance of the 270 Winchester and 280 Remington.

- 7 mm Remington Magnum: A long-range hunting round.

- 7.62×39mm: The standard Soviet/ComBloc rifle round from the mid-1940s to the mid-1970s, this is easily one of the most widely distributed rounds in the world due to the distribution of the ubiquitous Kalashnikov AK-47 series.

- 7.62×51mm NATO: This was the standard NATO rifle round until its replacement by the 5.56×45mm. It is currently the standard NATO sniper rifle and medium machinegun chambering. In the 1950s it was the standard NATO round for rifles, but recoil and weight proved problematic for the new battle rifle designs such as the FN FAL. Standardized commercially as the 308 Winchester.

- 7.62×54mmR: The standard Russian rifle round from the 1890s to the mid-1940s. The "R" stands for rimmed. The 7.62×54mmR rifle round is a Russian design dating back to 1891. Originally designed for the Mosin-Nagant rifle, it was used during the late Tsarist era and throughout the Soviet period, in machine guns and rifles such as the SVT-40. The Winchester Model 1895 was also chambered for this cartridge per a contract with the Russian government. It is still in use by the Russian military in the Dragunov and other sniper rifles and some machine guns. The round is colloquially known as the "7.62 Russian". This name sometimes causes people to confuse this round with the "7.62 Soviet" round, which refers to the 7.62 × 39 round used in the SKS and AK-47 rifles.

- 7.65×17mm Browning SR (32 ACP): A very small pistol round. However, this was the predominant Police Service round in Europe until the mid-1970s. The "SR" stands for semi-rimmed, meaning the case rim is slightly larger than the case body diameter.

- 8×57mm IS: The standard German service rifle round from 1888 to 1945, the 8×57mmIS (aka 8 mm Mauser) has seen wide distribution around the globe through commercial, surplus, and military sales, and is still a popular and commonly used hunting round in most of Europe, partly because of the abundance of affordable hunting rifles in this chambering as well as a broad availability of different hunting, target, and military surplus ammunition available.[54]

- 9×19mm Parabellum: Invented for the German military at the turn of the 20th century, the wide distribution of the 9×19mm Parabellum round made it the logical choice for the NATO standard pistol and Submachine gun round.

- 9.3×62mm: Very common big game hunting round in Scandinavia along with the 6.5×55mm, where it is used as a very versatile hunting round on anything from small and medium game with lightweight cast lead bullets to the largest European big game with heavy soft point hunting bullets. The 9.3×62mm is also very popular in the rest of Europe for Big game, especially driven Big game hunts due to its effective stopping power on running game. And, it is the single round smaller than the 375 H&H Magnum that has routinely been allowed for legal hunting of dangerous African species.

- 12.7×108mm: The 12.7×108mm round is a heavy machine gun and anti-materiel rifle round used by the Soviet Union, the former Warsaw Pact, modern Russia, and other countries. It is the approximate Russian equivalent of the NATO .50 BMG (12.7×99mm NATO) round. The differences between the two are the bullet shape, the types of powder used, and that the case of the 12.7×108mm is 9 mm longer and marginally more powerful.

- 14.5×114mm: The 14.5×114 mm is a heavy machine gun and anti-materiel rifle round used by the Soviet Union, the former Warsaw Pact, modern Russia, and other countries. Its most common use is in the KPV heavy machine gun found on several Russian Military vehicles.

Snake shot

Snake shot (AKA: bird shot, rat shot and dust shot)[55] refers to handgun and rifle rounds loaded with small lead shot. Snake shot is generally used for shooting at snakes, rodents, birds, and other pests at very close range.

The most common snake shot cartridge is .22 Long Rifle loaded with No. 12 shot. From a standard rifle these can produce effective patterns only to a distance of about 3 metres (10 ft) – but in a smoothbore shotgun this can extend as far as 15 metres (50 ft).

Caseless ammunition

Many governments and companies continue to develop caseless ammunition [citation needed] (where the entire case assembly is either consumed when the round fires or whatever remains is ejected with the bullet). So far, none has been successful enough to reach the civilian market and gain commercial success. Even within the military market, use is limited. Around 1848, Sharps introduced a rifle and paper cartridge (containing everything but the primer) system. When new, these guns had significant gas leaks at the chamber end, and with use these leaks progressively worsened. This problem plagues caseless cartridges and gun systems to this day.

The Daisy Heddon VL Single Shot Rifle, which used a caseless round in .22 caliber, was produced by the air gun company, beginning in 1968. Apparently, Daisy never considered the gun an actual firearm. In 1969, the ATF ruled it was in fact a firearm, which Daisy was not licensed to produce. Production of the guns and the ammo was discontinued in 1969. They are still available on the secondary market, mainly as collector items, as most owners report that accuracy is not very good.[56]

In 1989, Heckler & Koch, a prominent German firearms manufacturer, began advertising the G11 assault rifle, which shot a 4.73×33 square caseless round. The round was mechanically fired, with an integral primer.[citation needed]

In 1993 Voere of Austria began selling a gun and caseless ammunition. Their system used a primer, electronically fired at 17.5 ± 2 volts. The upper and lower limits prevent fire from either stray currents or static electricity. The direct electrical firing eliminates the mechanical delays associated with a striker, reducing lock time and allowing for easier adjustment of the rifle trigger.[citation needed]

In both instances, the "case" was molded directly from solid nitrocellulose, which is itself relatively strong and inert. The bullet and primer were glued into the propellant block.[citation needed]

Trounds

The "Tround" ("Triangular Round") was a unique type of cartridge designed in 1958 by David Dardick, for use in specially designed Dardick 1100 and Dardick 1500 open-chamber firearms. As their name suggests, Trounds were triangular in cross-section and were made of plastic or aluminum, with the cartridge completely encasing the powder and projectile. The Tround design was also produced as a cartridge adaptor, to allow conventional .38 Special and 22 Long Rifle cartridges to be used with the Dardick firearms.[citation needed]

Eco-friendly cartridges

They are meant to prevent pollution and are mostly biodegradable (metals being the exception) or fully. They are also meant to be used on older guns.[57]

Blank ammunition

- 7.62×51mm NATO (left)

- 9×19mm Parabellum (right).

A blank is a charged cartridge that does not contain a projectile or alternatively uses a non-metallic (for instance, wooden) projectile that pulverizes when hitting a blank firing adapter. To contain the propellant, the opening where the projectile would normally be located is crimped shut, and/or it is sealed with some material that disperses rapidly upon leaving the barrel.

This sealing material can still potentially cause harm at extremely close range. Actor Jon-Erik Hexum died when he shot himself in the head with a blank, and actor Brandon Lee was famously killed during the filming of The Crow when a blank fired behind a bullet that was stuck in the bore drove that bullet through his abdomen and into his spine. The gun had not been properly deactivated and a primed case with a bullet instead of a dummy had been used previously. Someone pulled the trigger and the primer drove the bullet silently into the bore.

Blanks are used in training, but do not always cause a gun to behave the same as live ammunition does; recoil is always far weaker, and some automatic guns only cycle correctly when the gun is fitted with a blank-firing adaptor to confine gas pressure within the barrel to operate the gas system.

Blanks can also be used to launch a rifle grenade, although later systems used a "bullet trap" design that captures a bullet from a conventional round, speeding deployment. This also negates the risk of mistakenly firing a live bullet into the rifle grenade, causing it to instantly explode instead of propelling it forward.

Blanks are also used as dedicated launchers for propelling a grappling hook, rope line or flare, or for a training lure for training gun dogs.

The power loads used in a variety of nail guns are essentially rimfire blanks.[citation needed]

Dummy rounds

Drill rounds are inert versions of cartridges used for education and practice during military training. Other than the lack of propellant and primer, these are the same size as normal cartridges and will fit into the mechanism of a gun in the same way as a live cartridge does. Because dry-firing (releasing the firing pin with an empty chamber) a gun can sometimes lead to firing pin (striker) damage, dummy rounds termed snap caps are designed to protect centerfire guns from possible damage during "dry-fire" trigger control practices.

To distinguish drill rounds and snap-caps from live rounds these are marked distinctively. Several forms of markings are used; e.g. setting colored flutes in the case, drilling holes through the case, coloring the bullet or cartridge, or a combination of these. In the case of centerfire drill rounds, the primer will often be absent, its mounting hole in the base is left open. Because these are mechanically identical to live rounds, which are intended to be loaded once, fired, and then discarded, drill rounds have a tendency to become significantly worn and damaged with repeated passage through magazines and firing mechanisms, and must be frequently inspected to ensure that these are not so degraded as to be unusable. For example, the cases can become torn or misshapen and snag on moving parts, or the bullet can become separated and stay in the breech when the case is ejected.[citation needed]

Mek-Porek

The brightly-colored Mek-Porek is an inert cartridge base designed to prevent a live round from being unintentionally chambered, to reduce the chances of an accidental discharge from mechanical or operator failure. An L-shaped flag is visible from the outside so that the shooter and other people concerned are instantly aware of the situation of the weapon. The Mek-Porek is usually tethered to its weapon by a short string and can be quickly ejected to make way for a live round if the situation suddenly warrants it. This safety device is standard-issue in the Israel Defense Forces.[58]

Snap cap

A snap cap is a device that is shaped like a standard cartridge but contains no primer, propellant, or projectile. It is used to ensure that dry firing firearms of certain designs does not cause damage. A small number of rimfire and centerfire firearms of older design should not be test-fired with the chamber empty, as this can lead to weakening or breakage of the firing pin and increased wear to other components in those firearms. In the instance of a rimfire weapon of primitive design, dry firing can also cause deformation of the chamber edge. For this reason, some shooters use a snap cap in an attempt to cushion the weapon's firing pin as it moves forward. Some snap caps contain a spring-dampened fake primer, or one made of plastic, or none at all; the springs or plastic absorb force from the firing pin, allowing the user to safely test the function of the firearm action without damaging its components.

Snap caps and action-proving dummy rounds also work as a training tool to replace live rounds for loading and unloading drills, as well as training for misfires or other malfunctions, as they function identically to a live "dud" round that has not ignited. Usually, one snap-cap is usable for 300 to 400 clicks.[citation needed] After that, due to the hole at the false primer, the firing pin does not reach it.

See also

- Ammunition box

- Antique guns

- List of handgun cartridges

- List of Magnum pistol cartridges

- List of rebated rim cartridges

- List of rifle cartridges

- Table of handgun and rifle cartridges

Notes

- ↑ The US did not sign the complete Hague Convention of 1899 in any case, but still follows its guidelines in military conflicts.

References

- ↑ "Glossary – SAAMI". Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20200804173256/https://saami.org/saami-glossary/?letter=C. Retrieved 2 April 2021. "CARTRIDGE: A single round of ammunition consisting of the case, primer and propellant with or without one or more projectiles. Also applies to a shotshell."

- ↑ "DEFINITIONS OF C.I.P. TERMS". Commission internationale permanente pour l'épreuve des armes à feu portatives. 2001. https://www.cip-bobp.org/homologation/uploads/ciptexts/definition-calibrage-en.pdf. Retrieved 2 April 2021. "Cartridge – Cartouche: A means to fire a propellant charge by means of a percussion device, with or without a projectile, all contained in a case."

- ↑ Sparano, Vin T. (2000). "Cartridges". The Complete Outdoors Encyclopedia. Macmillan. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-312-26722-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=iTX3BYBnOTcC&pg=PA37.

- ↑ "Short Action vs Long Action Rifles Explained". American Gun Association. 3 August 2020. https://blog.gunassociation.org/short-action-vs-long-action-rifles/.

- ↑ "Mass, Weight, Density or Specific Gravity of Different Metals". https://www.simetric.co.uk/si_metals.htm.

- ↑ "Lead". https://basc.org.uk/lead/. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ Howard, Edward (1800) "On a New Fulminating Mercury", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 90 (1): 204–238.

- ↑ Edward Charles Howard at National Portrait Gallery

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Fadala, Sam (17 November 2006). The Complete Blackpowder Handbook. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. pp. 159–161. ISBN 0-89689-390-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Dzxyneq43AEC&pg=PA160.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Sam Fadala (2006). The Complete Blackpowder Handbook. Krause Publications. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-89689-390-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=Dzxyneq43AEC&pg=PA158.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Joshua Shaw". http://www.researchpress.co.uk/firearms/ignition/shaw02.htm.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Hamilton, Douglas Thomas (1916). Cartridge manufacture; a treatise covering the manufacture of rifle cartridge cases, bullets, powders, primers and cartridge clips, and the designing and making of the tools used in connection with the production of cartridge cases and bullets. New York: The Industrial Press. http://archive.org/details/cartridgemanufac00hamirich. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ↑ "Mitrailleuse Ammunition". https://www.victorianshipmodels.com/antitorpedoboatguns/Mitrailleuse/mitrailleuseammu.html.

- ↑ "British Military Small Arms Ammo - .577 inch Ball Pattern I to V". https://sites.google.com/site/britmilammo/-577-inch-snider/-577-inch-ball-pattern-i-to-v.

- ↑ "British Military Small Arms Ammo - .45 Martini-Henry Solid Case Rifle". https://sites.google.com/site/britmilammo/-450-inch-martini-henry/-45-martini-henry-drawn-case.

- ↑ "Hotchkiss Ammunition". http://www.victorianshipmodels.com/antitorpedoboatguns/Hotchkiss/hotchkissammunit.html.

- ↑ "Unsafe Firearm-Ammunition Combinations". SAAMI. 6 March 2012. http://www.saami.org/specifications_and_information/publications/download/SAAMI_ITEM_211-Unsafe_Arms_and_Ammunition_Combinations.pdf.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Greener, William Wellington (1907), "Ammunition and Accessories.–Cartridges", The Gun and Its Development, Cassell, pp. 570, 589, https://books.google.com/books?id=3HMCAAAAYAAJ, retrieved 22 March 2017

- ↑ Nickel, Helmut; Pyhrr, Stuart W.; Tarassuk, Leonid (2013). The Art of Chivalry: European Arms and Armor from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 174. ISBN 978-0300199413.

- ↑ Metschl, John (1928). "The Rudolph J. Nunnemacher Collection of Projectile Arms". Bulletin of the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee 9: 60.

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, article on "cartridge" (subsection: "cartridge-paper").

- ↑ U.S. Army (September 1984), Military Explosives, Technical Manual, Department of the Army, TM 9-1300-214, p. 2-3, stating "1590. Cartridges with ball and power combined were introduced for small arms."

- ↑ U.S. Army 1984, pp. 2–3 indicates the period 1611–1632 and states the improved cartridge increased the rate of fire for the Thirty Years' War.

- ↑ Sharpe, Philip B. (1938), "The Development of the Cartridge", The Rifle in America, New York: William Morrow, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Greener 1907, p. 570

- ↑ Sharpe 1938, p. 30

- ↑ Scott, Christopher L.; Turton, Alan; Gruber von Arni, Eric (2004). Edgehill: The Battle Reinterpreted. Pen and Sword. pp. 9–12. ISBN 978-1844152544.

- ↑ Winant, Lewis (1959). Early Percussion Firearms. Great Britain: Herbert Jenkins Ltd. pp. 145–146. ISBN 0-600-33015-X

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Chemical Analysis of Firearms, Ammunition, and Gunshot Residue" by James Smyth Wallace p. 24.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 http://www.sil.si.edu/smithsoniancontributions/HistoryTechnology/pdf_hi/SSHT-0011.pdf .

- ↑ Firearms by Roger Pauly p. 94.

- ↑ A History of Firearms by W. Y. Carman p. 121.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Kinard, Jeff (2004) Pistols: An Illustrated History of Their Impact, ABC-CLIO, p. 109

- ↑ "Cabela's still sells black powder pistols; remain in use for hunting". http://www.cabelas.com/category/Pistols-Revolvers/104503680.uts.

- ↑ "History of firearms" (fireadvantages.com)

- ↑ "How guns work" (fireadvantages.com)

- ↑ Flayderman, Norm (2007). Flayderman's Guide to Antique American Firearms and Their Values (9 ed.). Iola, Wisconsin: F+W Media, Inc. p. 775. ISBN 978-0-89689-455-6.

- ↑ Barnes, Frank C.; Bodinson, Holt (2009). "Amrerican Rimfire Cartridges". Cartridges of the World: A Complete and Illustrated Reference for Over 1500 Cartridges. Iola, Wisconsin: Gun Digest Books. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-89689-936-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=3_-kUkNXTNwC&pg=PA441. Retrieved 25 January 2012.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Shooting section (la section de tir) of the official website (in French) of a modern indoor shooting association in Belgium, Les Arquebusier de Visé.

- ↑ Les Lefaucheux , by Maître Simili, Spring 1990 (in French)

- ↑ "An example of a Benjamin Houllier gun manufactured in association with the gunsmith Blanchard". Littlegun.info. http://www.littlegun.info/arme%20francaise/artisans%20e%20f%20g%20h%20i%20j/a%20houllier%20blanchar%20gb.htm.

- ↑ "An example of a Benjamin Houllier gun manufactured in association with the gunsmiths Blanchard and Charles Robert". Littlegun.info. http://www.littlegun.info/arme%20francaise/artisans%20e%20f%20g%20h%20i%20j/a%20houllier%20blanchar%20et%20ch%20robert%20gb.htm.

- ↑ "Early Percussion Firearms". Spring Books. 25 October 2015. https://books.google.com/books?id=DjWpnQEACAAJ&q=Early+Percussion+Firearms.

- ↑ "Annales de la propriété industrielle, artistique et littéraire". Au bureau des Annales. 10 April 1863. https://books.google.com/books?id=SzEwAQAAMAAJ&q=Perrin+1839+Arme&pg=PA186.

- ↑ Cartridges of the World, various editions and articles.