History of the electric vehicle

Topic: Engineering

From HandWiki - Reading time: 51 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 51 min

Crude electric carriages were first invented in the late 1820s and 1830s. Practical, commercially available electric vehicles appeared during the 1890s. An electric vehicle held the vehicular land speed record until around 1900. In the early 20th century, the high cost, low top speed, and short-range of battery electric vehicles, compared to internal combustion engine vehicles, led to a worldwide decline in their use as private motor vehicles. Electric vehicles have continued to be used for loading and freight equipment and for public transport – especially rail vehicles.

At the beginning of the 21st century, interest in electric and alternative fuel vehicles in private motor vehicles increased due to: growing concern over the problems associated with hydrocarbon-fueled vehicles, including damage to the environment caused by their emissions; the sustainability of the current hydrocarbon-based transportation infrastructure; and improvements in electric vehicle technology.

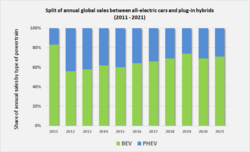

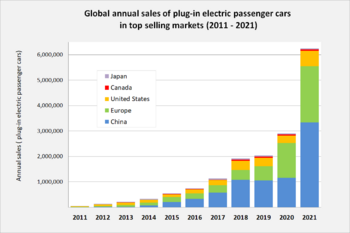

Since 2010, combined sales of all-electric cars and utility vans achieved 1 million units delivered globally in September 2016,[1] 4.8 million electric cars in use at the end of 2019,[2] and cumulative sales of light-duty plug-in electric cars reached the 10 million unit milestone by the end of 2020.[3] The global ratio between annual sales of battery electric cars and plug-in hybrids went from 56:44 in 2012 to 74:26 in 2019, and fell to 69:31 in 2020.[3][4][5] As of August 2020[update], the fully electric Tesla Model 3 is the world's all-time best selling plug-in electric passenger car, with around 645,000 units.[6]

Early history

Electric model cars

Designs of electric motors by individuals such as Benjamin Franklin led to ideas for electric vehicles.[7][8][9] The invention of the first model electric vehicle is attributed to various people.[10] In 1828, the Hungarian priest and physicist Ányos Jedlik invented an early type of electric motor, and created a small model car powered by his new motor. Between 1832 and 1839, Scottish inventor Robert Anderson also invented a crude electric carriage.[11] In 1835, Professor Sibrandus Stratingh of Groningen, the Netherlands and his assistant Christopher Becker from Germany also created a small-scale electric car, powered by non-rechargeable primary cells.[12]

Electric locomotives

In 1834, Vermont blacksmith Thomas Davenport built a similar contraption which operated on a short, circular, electrified track.[13] The first known electric locomotive was built in 1837, in Scotland by chemist Robert Davidson of Aberdeen. It was powered by galvanic cells (batteries). Davidson later built a larger locomotive named Galvani, exhibited at the Royal Scottish Society of Arts Exhibition in 1841. The 7,100 kg (7-long-ton) vehicle had two direct-drive reluctance motors, with fixed electromagnets acting on iron bars attached to a wooden cylinder on each axle, and simple commutators. It hauled a load of 6,100 kg (6 long tons) at 6.4 km/h (4 mph) for a distance of 2.4 km (1.5 mi). It was tested on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway in September of the following year, but the limited power from batteries prevented its general use. It was destroyed by railway workers, who saw it as a threat to their security of employment.[14][15][16][17]

A patent for the use of rails as conductors of electric current was granted in England in 1840, and similar patents were issued to Lilley and Colten in the United States in 1847.[18] The first battery rail car was used in 1887 on the Royal Bavarian State Railways.[19]

First full-scale electric cars

Rechargeable batteries that provided a viable means for storing electricity on board a vehicle did not come into being until 1859, with the invention of the lead–acid battery by French physicist Gaston Planté.[20][21] Camille Alphonse Faure, another French scientist, significantly improved the design of the battery in 1881; his improvements greatly increased the capacity of such batteries and led directly to their manufacture on an industrial scale.[22]

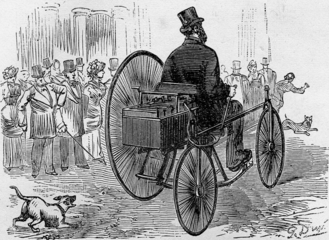

What is likely the first human-carrying electric vehicle with its own power source was tested along a Paris street in April 1881 by French inventor Gustave Trouvé.[23] In 1880 Trouvé improved the efficiency of a small electric motor developed by Siemens (from a design purchased from Johann Kravogl (de) in 1867) and using the recently developed rechargeable battery, fitted it to an English James Starley tricycle, so inventing the world's first electric vehicle.[24] Although this was successfully tested on 19 April 1881 along the Rue Valois in central Paris, he was unable to patent it.[25] Trouvé swiftly adapted his battery-powered motor to marine propulsion; to make it easy to carry his marine conversion to and from his workshop to the nearby River Seine, Trouvé made it portable and removable from the boat, thus inventing the outboard motor. On 26 May 1881, the 5-metre Trouvé boat prototype, called Le Téléphone reached a speed of 3.6 km/h (2.2 mph) going upstream and 9.0 km/h (5.6 mph) downstream.[26]

English inventor Thomas Parker, who was responsible for innovations such as electrifying the London Underground, overhead tramways in Liverpool and Birmingham, and the smokeless fuel coalite, built his first electric car in Wolverhampton in 1884, although the only documentation is a photograph from 1895.[27]

Parker's long-held interest in the construction of more fuel-efficient vehicles led him to experiment with electric vehicles. He also may have been concerned about the malign effects smoke and pollution were having in London.[28] Production of the car was in the hands of the Elwell-Parker Company, established in 1882 for the construction and sale of electric trams. The company merged with other rivals in 1888 to form the Electric Construction Corporation; this company had a virtual monopoly on the British electric car market in the 1890s. The company manufactured the first electric 'dog cart' in 1896.[29]

France and the United Kingdom were the first nations to support the widespread development of electric vehicles.[11] German engineer Andreas Flocken built the first real electric car in 1888.[30][31][32][33]

Electric trains were also used to transport coal out of mines, as their motors did not use up precious oxygen. Before the pre-eminence of internal combustion engines, electric automobiles also held many speed and distance records.[34] Among the most notable of these records was the breaking of the 100 km/h (62 mph) speed barrier, by Camille Jenatzy on 29 April 1899 in his 'rocket-shaped' vehicle Jamais Contente, which reached a top speed of 105.88 km/h (65.79 mph). Also notable was Ferdinand Porsche's design and construction of an all-wheel drive electric car, powered by a motor in each hub, which also set several records in the hands of its owner E.W. Hart.

The first electric car in the United States was developed in 1890–91 by William Morrison of Des Moines, Iowa; the vehicle was a six-passenger wagon capable of reaching a speed of 23 km/h (14 mph). It was not until 1895 that consumers began to devote attention to electric vehicles after A.L. Ryker introduced the first electric tricycles to the U.S.[35]

-

Gustave Trouvé's tricycle (1881), world's first electric car

-

Electric car built in England by Thomas Parker, photo from 1895

-

Flocken Elektrowagen, 1888 (reconstruction, 2011)

-

Columbia Electric's (1896–99) "Victoria" electric cab on Pennsylvania Ave., Washington D.C., seen from Lafayette Square in 1905, driving in front of the White House.

-

German electric car, 1904, with the chauffeur on top

1890s-1910s: Golden age

Interest in motor vehicles increased greatly in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Electric battery-powered taxis became available at the end of the 19th century. In London, Walter Bersey designed a fleet of such cabs and introduced them to the streets of London in 1897.[36] They were soon nicknamed "Hummingbirds" due to the idiosyncratic humming noise they made.[37] In the same year in New York City, the Samuel's Electric Carriage and Wagon Company began running 12 electric hansom cabs.[38] The company ran until 1898 with up to 62 cabs operating until it was reformed by its financiers to form the Electric Vehicle Company.[39]

Electric vehicles had a number of advantages over their early-1900s competitors. They did not have the vibration, smell, and noise associated with gasoline cars. They also did not require gear changes. (While steam-powered cars also had no gear shifting, they suffered from long start-up times of up to 45 minutes on cold mornings.) The cars were also preferred because they did not require a manual effort to start, as did gasoline cars which featured a hand crank to start the engine.

Electric cars found popularity among well-heeled customers who used them as city cars, where their limited range proved to be even less of a disadvantage.

Acceptance of electric cars was initially hampered by a lack of power infrastructure.[40] In the United States by the turn of the century, 40 per cent of automobiles were powered by steam, 38 per cent by electricity, and 22 per cent by petrol. A total of 33,842 electric cars were registered in the United States, and the U.S. became the country where electric cars had gained the most acceptance.[41] Most early electric vehicles were massive, ornate carriages designed for the upper-class customers that made them popular. They featured luxurious interiors and were replete with expensive materials. Electric vehicles were often marketed as luxury cars for women, which may have generated a stigma among male consumers.[42][43] Sales of electric cars peaked in the early 1910s. There were over 300 listed manufacturers who produced a vehicle in the United States until 1942.[44]

In 1910s, The Standard Electric used Westinghouse electric motors and claimed to have a range of 110 miles on a charge. It was operated by a tiller from the left-hand side. The controller had six forward speeds, and had a top speed of 20-mph. The model M was a closed model Coupe or open Runabout, and priced from $1,785 to $1,900.[45]

Power as a service and General Vehicle

To overcome the limited operating range of electric vehicles, and the lack of recharging infrastructure, an exchangeable battery service was first proposed as early as 1896.[46] The concept was first put into practice by Hartford Electric Light Company through the GeVeCo battery service and was initially available for electric trucks. The vehicle owner purchased the vehicle from General Vehicle Company (GVC, a subsidiary of the General Electric Company) without a battery and the electricity was purchased from Hartford Electric through an exchangeable battery. The owner paid a variable per-mile charge and a monthly service fee to cover the maintenance and storage of the truck. Both vehicles and batteries were modified to facilitate a fast battery exchange. The service was provided between 1910 and 1924 and during that period covered more than 6 million miles. Beginning in 1917 a similar successful service was operated in Chicago for owners of Milburn Wagon Company cars who also could buy the vehicle without the batteries.[46]

In New York City , in the pre-World War I era, ten electric vehicle companies banded together to form the New York Electric Vehicle Association.[47] The association included manufacturers and dealers, among them General Motors' truck division, and the aforementioned General Vehicle division of General Electric, which claimed to have almost 2,000 operating vehicles in the metropolitan region.[48] When opening their flagship department store, Lord and Taylor boasted of its electric vehicle fleet – numbering 38 trucks – and the conveyor system to efficiently load and unload goods.[48][49]

-

Thomas Edison and an electric car in 1913

-

1912 Detroit Electric advertisement

1920s–1950s: Dark age of Electric Vehicles

After enjoying success at the beginning of the 20th century, the electric car began to lose its position in the automobile market. A number of developments contributed to this situation. By the 1920s an improved road infrastructure improved travel times, creating a need for vehicles with a greater range than that offered by electric cars. Worldwide discoveries of large petroleum reserves led to the wide availability of affordable petrol, making petrol-powered cars cheaper to operate over long distances. Electric cars were limited to urban use by their slow speed (no more than 24–32 km/h or 15–20 mph[41]) and low range (50–65 km or 30–40 miles[41]), and gasoline cars were now able to travel farther and faster than equivalent electrics.

Gasoline cars also overcame much of their negatives compared to electrics, in several areas. Whereas ICE cars originally had to be hand-cranked to start – a difficult and sometimes dangerous activity – the invention of the electric starter by Charles Kettering in 1912[50] eliminated the need of a hand starting crank. Further, while gasoline engines are inherently noisier than electric motors, the invention of the muffler by Milton O. Reeves and Marshall T. Reeves in 1897 significantly reduced the noise to tolerable levels. Finally, the initiation of mass production of gas-powered vehicles by Henry Ford brought their price down.[51] By contrast, the price of similar electric vehicles continued to rise; by 1912, an electric car sold for almost double the price of a gasoline car.[11]

Most electric car makers stopped production at some point in the 1910s. Electric vehicles became popular for certain applications where their limited range did not pose major problems. Forklift trucks were electrically powered when they were introduced by Yale in 1923.[52] In Europe, especially the United Kingdom, milk floats were powered by electricity, and for most of the 20th century the majority of the world's battery electric road vehicles were British milk floats.[53] Electric golf carts were produced by Lektro as early as 1954.[54] By the 1920s, the early heyday of electric cars had passed, and a decade later, the electric automobile industry had effectively disappeared.[55]

Years passed without a major revival in the use of electric cars. Fuel-starved European countries fighting in World War II experimented with electric cars such as the British milk floats and the French Bréguet Aviation car, but overall, while ICE development progressed at a brisk pace, electric vehicle technology stagnated. In the late 1950s, Henney Coachworks and the National Union Electric Company, makers of Exide batteries, formed a joint venture to produce a new electric car, the Henney Kilowatt, based on the French Renault Dauphine. The car was produced in 36-volt and 72-volt configurations.[56] The 72-volt models had a top speed approaching 96 km/h (60 mph) and could travel for nearly an hour on a single charge. Despite Kilowatt's improved performance with respect to previous electric cars, it was about double the cost of a regular gasoline-powered Dauphine, and production ended in 1961.[57]

-

Electric vehicle TAMA, produced by Tachikawa Aircraft Company in 1947. Mechanical Engineering Heritage (Japan) No. 40

-

East German electric vans of the Deutsche Post in 1953

-

The Henney Kilowatt, a 1961 production electric car

1960s–1990s: Revival of interest

In 1959, American Motors Corporation (AMC) and Sonotone Corporation announced a joint research effort to consider producing an electric car powered by a "self-charging" battery.[58] AMC had a reputation for innovation in economical cars while Sonotone had technology for making sintered plate nickel-cadmium batteries that could be recharged rapidly and weighed less than traditional lead-acid versions.[59] That same year, Nu-Way Industries showed an experimental electric car with a one-piece plastic body that was to begin production in early 1960.[58]

In the mid-1960s a few battery-electric concept cars appeared, such as the Scottish Aviation Scamp (1965),[60] and an electric version of General Motors gasoline car, the Electrovair (1966).[61] None of them entered production. The 1973 Enfield 8000 did make it into small-scale production, 112 were eventually produced.[62] In 1967, AMC partnered with Gulton Industries to develop a new battery based on lithium and a speed controller designed by Victor Wouk.[63] A nickel-cadmium battery supplied power to an all-electric 1969 Rambler American station wagon.[63] Other "plug-in" experimental AMC vehicles developed with Gulton included the Amitron (1967) and the similar Electron (1977).[64]

On 31 July 1971, an electric car received the unique distinction of becoming the first crewed vehicle to drive on the Moon; that car was the Lunar Roving Vehicle, which was first deployed during the Apollo 15 mission. The "Moon buggy" was developed by Boeing and GM subsidiary Delco Electronics (co-founded by Kettering)[50] featured a DC drive motor in each wheel, and a pair of 36-volt silver-zinc potassium hydroxide non-rechargeable batteries.

After years outside the limelight, the energy crises of the 1970s and 1980s brought about renewed interest in the perceived independence electric cars had from the fluctuations of the hydrocarbon energy market. However, vehicles such as the intensely-marketed Sinclair C5 failed.[65] General Motors created a concept car using another gasoline car as the base, the Electrovette (1976). At the 1990 Los Angeles Auto Show, General Motors President Roger Smith unveiled the GM Impact electric concept car, along with the announcement that GM would build electric cars for sale to the public.

From the 1960s to the 1990s, a number of companies made battery electric vehicles converted from existing manufactured models, often using gliders. None were sold in large numbers, with sales hampered by high cost and a limited range. Most of these vehicles were sold to government agencies and electric utility companies. The passage of the Electric and Hybrid Vehicle Research, Development and Demonstration Act of 1976 in the US provided government incentives for development of electric vehicles in the US.[66] Electric Fuel Propulsion Corporation (now Apollo Energy Systems) produced the Electrosport (a converted AMC Hornet), the Mars I (a converted Renault Dauphine), and the Mars II (a converted Renault R-10). Jet Industries sold the Electra-Van 600 (a converted Subaru Sambar 600), the Electra-Van 750 (converted Mazda B2000/Ford Courier pickup trucks), the Electrica (converted Ford Escort/Mercury Lynx cars) and the Electrica 007 (converted Dodge Omni 024/Plymouth Horizon TC3 cars). U.S. Electricar Corp., based in Massachusetts, sold the Lectric Leopard, a converted Renault 5.[67] Electric Vehicle Associates sold the Current Fare (a converted Ford Fairmont) and the Change of Pace (a converted AMC Pacer).[68] U.S. Electricar, Inc., based in California, sold a converted Geo Prizm.[69] Solectria Corporation (now Azure Dynamics) sold the Solectria Force (a converted Geo Metro) and the E10 (a converted Chevrolet S-10). Later, General Motors would also produce an electric S-10, the Chevrolet S-10 EV, based on the General Motors EV1.[70]

In the early 1990s, the California Air Resources Board (CARB), the government of California's "clean air agency", began a push for more fuel-efficient, lower-emissions vehicles, with the ultimate goal being a move to zero-emissions vehicles such as electric vehicles.[71][72] In response, automakers developed electric models, including the Chrysler TEVan, Ford Ranger EV pickup truck, GM EV1 and S10 EV pickup, Honda EV Plus hatchback, Nissan lithium-battery Altra EV miniwagon and Toyota RAV4 EV. The Altra was notable for being the first production EV to use lithium-ion batteries.[73] [74] The automakers were accused of pandering to the wishes of CARB in order to continue to be allowed to sell cars in the lucrative Californian market, while failing to adequately promote their electric vehicles in order to create the impression that the consumers were not interested in the cars, all the while joining oil industry lobbyists in vigorously protesting CARB's mandate.[72] GM's program came under particular scrutiny; in an unusual move, consumers were not allowed to purchase EV1s, but were instead asked to sign closed-end leases, meaning that the cars had to be returned to GM at the end of the lease period, with no option to purchase, despite lease interest in continuing to own the cars.[72] Chrysler, Toyota, and a group of GM dealers sued CARB in Federal court.[75]

After public protests by EV drivers' groups upset by the repossession of their cars, Toyota offered the last 328 RAV4-EVs for sale to the general public for six months until 22 November 2002. Almost all other production electric cars were withdrawn from the market and were in some cases seen to have been destroyed by their manufacturers.[72] Toyota continues to support the several hundred Toyota RAV4-EVs in the hands of the general public and in fleet usage. GM famously de-activated the few EV1s that were donated to engineering schools and museums.[76]

Throughout the 1990s, interest in fuel-efficient or environmentally friendly cars declined among consumers in the United States, who instead favored sport utility vehicles, which were affordable to operate despite their poor fuel efficiency thanks to lower gasoline prices. Domestic U.S. automakers chose to focus their product lines on truck-based vehicles, which enjoyed larger profit margins than the smaller cars which were preferred in places like Europe or Japan.

Most electric vehicles on the world roads were low-speed, low-range neighborhood electric vehicles (NEVs). Pike Research estimated there were almost 479,000 NEVs on world roads in 2011.[77] As of July 2006[update], there were between 60,000 and 76,000 low-speed battery-powered vehicles in use in the United States, up from about 56,000 in 2004.[78] North America's top-selling NEV is the Global Electric Motorcars (GEM) vehicles, with more than 50,000 units sold worldwide by mid-2014.[79] The world's two largest NEV markets in 2011 were the United States, with 14,737 units sold, and France, with 2,231 units.[80] Other micro electric cars sold in Europe was the Kewet, since 1991, and replaced by the Buddy, launched in 2008.[81] Also the Th!nk City was launched in 2008 but production was halted due to financial difficulties.[82] Production restarted in Finland in December 2009.[83] The Th!nk was sold in several European countries and the U.S.[84][85] In June 2011 Think Global filed for bankruptcy and production was halted.[86] Worldwide sales reached 1,045 units by March 2011.[87] A total of 200,000 low-speed small electric cars were sold in China in 2013, most of which are powered by lead-acid batteries. These electric vehicles are not considered by the government as new energy vehicles due to safety and environmental concerns, and consequently, do not enjoy the same benefits as highway legal plug-in electric cars.[88]

-

Charging station with NEMA connector for electric AMC Gremlin used by Seattle City Light in 1973[89]

-

The Honda EV Plus, one of the cars introduced as a result of the CARB ZEV mandate

-

Three Lunar Roving Vehicles are currently parked on the Moon

-

Th!nk City and Buddy in Oslo, Norway

-

The General Motors EV1, one of the cars introduced due to the California Air Resources Board mandate, had a range of 260 km (160 miles) with NiMH batteries in 1999.

2000s: Modern highway-capable electric cars

California electric car maker Tesla Motors began development in 2004 on the Tesla Roadster, which was first delivered to customers in 2008.[90] The Roadster was the first production all-electric car to travel more than 320 km (200 miles) per charge.[91] Since 2008, Tesla sold approximately 2,450 Roadsters in over 30 countries through December 2012.[92] Tesla sold the Roadster until early 2012, when its supply of Lotus Elise gliders ran out, as its contract with Lotus Cars for 2,500 gliders expired at the end of 2011.[93][94] Tesla stopped taking orders for the Roadster in the U.S. market in August 2011,[95][96] and the 2012 Tesla Roadster was sold in limited numbers only in Europe, Asia and Australia.[97][98]

The Mitsubishi i-MiEV was launched in Japan for fleet customers in July 2009, and for individual customers in April 2010,[99][100][101] followed by sales to the public in Hong Kong in May 2010, and Australia in July 2010 via leasing.[102][103] The i-MiEV was launched in Europe in December 2010, including a rebadged version sold in Europe as Peugeot iOn and Citroën C-Zero.[104][105] The market launch in the Americas began in Costa Rica in February 2011, followed by Chile in May 2011.[106][107] Fleet and retail customer deliveries in the U.S. and Canada began in December 2011.[108][109][110] Accounting for all vehicles of the iMiEV brand, Mitsubishi reports around 27,200 units sold or exported since 2009 through December 2012, including the minicab MiEVs sold in Japan, and the units rebadged and sold as Peugeot iOn and Citroën C-Zero in the European market.[111]

Senior leaders at several large automakers, including Nissan and General Motors, have stated that the Roadster was a catalyst which demonstrated that there is pent-up consumer demand for more efficient vehicles. In an August 2009 edition of The New Yorker, GM vice-chairman Bob Lutz was quoted as saying, "All the geniuses here at General Motors kept saying lithium-ion technology is 10 years away, and Toyota agreed with us – and boom, along comes Tesla. So I said, 'How come some tiny little California startup, run by guys who know nothing about the car business, can do this, and we can't?' That was the crowbar that helped break up the log jam."[112]

2010s

The Nissan Leaf, introduced in Japan and the United States in December 2010, became the first modern all-electric, zero tailpipe emission five door family hatchback to be produced for the mass market from a major manufacturer.[114][115] As of January 2013[update], the Leaf is also available in Australia, Canada and 17 European countries.[116]

The Better Place network was the first modern commercial deployment of the battery swapping model. The Renault Fluence Z.E. was the first mass production electric car enable with switchable battery technology and sold for the Better Place network in Israel and Denmark.[117] Better Place launched its first battery-swapping station in Israel, in Kiryat Ekron, near Rehovot in March 2011. The battery exchange process took five minutes.[118] As of December 2012[update], there were 17 battery switch stations fully operational in Denmark enabling customers to drive anywhere across the country in an electric car.[119] By late 2012 the company began to suffer financial difficulties, and decided to put on hold the roll out in Australia and reduce its non-core activities in North America, as the company decided to concentrate its resources on its two existing markets.[120][121][122] On 26 May 2013, Better Place filed for bankruptcy in Israel.[123] The company's financial difficulties were caused by the high investment required to develop the charging and swapping infrastructure, about US$850 million in private capital, and a market penetration significantly lower than originally predicted by Shai Agassi. Less than 1,000 Fluence Z.E. cars were deployed in Israel and around 400 units in Denmark.[124][125]

The Smart electric drive, Wheego Whip LiFe, Mia electric, Volvo C30 Electric, and the Ford Focus Electric were launched for retail customers during 2011. The BYD e6, released initially for fleet customers in 2010, began retail sales in Shenzhen, China in October 2011.[126] The Bolloré Bluecar was released in December 2011 and deployed for use in the Autolib' carsharing service in Paris.[127] Leasing to individual and corporate customers began in October 2012 and is limited to the Île-de-France area.[128] In February 2011, the Mitsubishi i MiEV became the first electric car to sell more than 10,000 units, including the models badged in Europe as Citroën C-Zero and Peugeot. The record was officially registered by Guinness World Records. Several months later, the Nissan Leaf overtook the i MiEV as the best selling all-electric car ever,[129] and by February 2013 global sales of the Leaf reached the 50,000 unit mark.[116]

The next Tesla vehicle, the Model S, was released in the U.S. on 22 June 2012[130] and the first delivery of a Model S to a retail customer in Europe took place on 7 August 2013.[131] Deliveries in China began on 22 April 2014.[132] The next model was the Tesla Model X.[133] Other models released to the market in 2012 and 2013 include the BMW ActiveE, Coda, Renault Fluence Z.E., Honda Fit EV, Toyota RAV4 EV, Renault Zoe, Roewe E50, Mahindra e2o, Chevrolet Spark EV, Mercedes-Benz SLS AMG Electric Drive, Fiat 500e, Volkswagen e-Up!, BMW i3, and Kandi EV. Toyota released the Scion iQ EV in the U.S. (Toyota eQ in Japan) in 2013. The car production is limited to 100 units. The first 30 units were delivered to the University of California, Irvine in March 2013 for use in its Zero Emission Vehicle-Network Enabled Transport (ZEV-NET) carsharing fleet. Toyota announced that 90 out of the 100 vehicles produced globally will be placed in carsharing demonstration projects in the United States and the rest in Japan.[134]

The Coda sedan went out of production in 2013, after selling only about 100 units in California. Its manufacturer, Coda Automotive, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on 1 May 2013. The company stated that it expects to emerge from the bankruptcy process to focus on energy storage solutions as it has decided to abandon car manufacturing.[135]

The Tesla Model S ranked as the top-selling plug-in electric car in North America during the first quarter of 2013 with 4,900 cars sold, ahead of the Nissan Leaf (3,695).[136] European retail deliveries of the Tesla Model S began in Oslo in August 2013,[137] and during its first full month in the market, the Model S ranked as the top-selling car in Norway with 616 units delivered, representing a market share of 5.1% of all the new cars sold in the country in September 2013, becoming the first electric car to top the new car sales ranking in any country, and contributing to a record all-electric car market share of 8.6% of new car sales during that month.[138][139] In October 2013, an electric car was the best selling car in the country for a second month in a row. This time was the Nissan Leaf with 716 units sold, representing a 5.6% of new car sales that month.[140][141]

The Renault–Nissan Alliance reached global sales of 100,000 all-electric vehicles in July 2013.[144] The 100,000th customer was a U.S. student who bought a Nissan Leaf.[145] In mid January 2014, global sales of the Nissan Leaf reached the 100,000 unit milestone, representing a 45% market share of worldwide pure electric vehicles sold since 2010.[146]

As of June 2014[update], there were over 500,000 plug-in electric passenger cars and utility vans in the world, with the U.S. leading plug-in electric car sales with a 45% share of global sales.[147][148] In September 2014, sales of plug-in electric cars in the United States reached the 250,000 unit milestone.[149] Global cumulative sales of the Tesla Model S passed the 50,000 unit milestone in October 2014.[150] In November 2014 the Renault–Nissan Alliance reached 200,000 all-electric vehicles delivered globally, representing a 58% share of the global light-duty all-electric market segment.[151]

The world's top-selling all-electric cars in 2014 were the Nissan Leaf (61,507), Tesla Model S (31,655), BMW i3 (16,052), and the Renault Zoe (11,323). Accounting for plug-in hybrids, the Leaf and the Model S also ranked first and second correspondingly among the world's top 10 selling plug-in electric cars.[143] All-electric models released to the retail customers in 2014 include the BMW Brilliance Zinoro 1E, Chery eQ, Geely-Kandi Panda EV, Zotye Zhidou E20, Kia Soul EV, Volkswagen e-Golf, Mercedes-Benz B-Class Electric Drive, and Venucia e30.

General Motors unveiled the Chevrolet Bolt EV concept car at the 2015 North American International Auto Show.[153] The Bolt is scheduled for availability in late 2016 as a model year 2017.[154] GM anticipates the Bolt will deliver an all-electric range more than 320 km (200 miles), with pricing starting at US$37,500 before any applicable government incentives.[155] The European version, marketed as the Opel Ampera-e, will go into production in 2017.[156]

In May 2015, global sales of highway legal all-electric passenger cars and light utility vehicles passed the 500,000 unit milestone, accounting for sales since 2008. Out these, Nissan accounts for about 35%, Tesla Motors about 15%, and Mitsubishi about 10%.[157] Also in May 2015, the Renault Zoe and the BMW i3 passed the 25,000 unit global sales milestone.[158] Worldwide sales of the Model S passed the 75,000 unit milestone in June 2015.[150]

By early June 2015, the Renault–Nissan Alliance continued as the leading all-electric vehicle manufacturer with global sales of over 250,000 pure electric vehicles representing about half of the global light-duty all-electric market segment. Nissan sales totaled 185,000 units, which includes the Nissan Leaf and the e-NV200 van. Renault has sold 65,000 electric vehicles, and its line-up includes the ZOE passenger car, the Kangoo Z.E. van, the SM3 Z.E. (previously Fluence Z.E.) sedan and the Twizy heavy quadricycle.[159]

By mid-September 2015, the global stock of highway legal plug-in electric passenger cars and utility vans passed the one million sales milestone, with the pure electrics capturing about 62% of global sales.[160] The United States is the plug-in segment market leader with a stock of over 363,000 plug-in electric cars delivered since 2008 through August 2015, representing 36.3% of global sales.[160] The state of California is the largest plug-in car regional market, with more than 158,000 units sold between December 2010 and June 2015, representing 46.5% of all plug-in cars sold in the U.S.[161][162][163][164] Until December 2014, California not only had more plug-in electric vehicles than any other state in the nation, but also more than any other country.[165][166]

As of August 2015[update], China ranked as the world's second top-selling country plug-in market, with over 157,000 units sold since 2011 (15.7%), followed by Japan with more than 120,000 plug-in units sold since 2009 (12.1%).[160] As of June 2015[update], over 310,000 light-duty plug-in electric vehicles have been registered in the European market since 2010.[167][168] European sales are led by Norway, followed by the Netherlands, and France.[160] In the heavy-duty segment, China is the world's leader, with over 65,000 buses and other commercial vehicles sold through August 2015.[160]

As of December 2015[update], global sales of electric cars were led by the Nissan Leaf with over 200,000 units sold making the Leaf the world's top-selling highway-capable electric car in history. The Tesla Model S, with global deliveries of more than 100,000 units, listed as the world's second best selling all-electric car of all time.[169] The Model S ranked as the world's best selling plug-in electric vehicle in 2015, up from second best in 2014.[170][171] The Model S was also the top-selling plug-in car in the U.S. in 2015.[172] Most models released in the world's markets to retail customers during 2015 were plug-in hybrids. The only new series production all-electric cars launched up to October 2015 were the BYD e5 and the Tesla Model X, together with several variants of the Tesla Model S line-up.[173]

The Tesla Model 3 was unveiled on 31 March 2016. With pricing starting at US$35,000 and an all-electric range of 345 km (215 miles), the Model 3 is Tesla Motors first vehicle aimed for the mass market. Before the unveiling event, over 115,000 people had reserved the Model 3.[175] As of 7 April 2016[update], one week after the event, Tesla Motors reported over 325,000 reservations, more than triple the 107,000 Model S cars Tesla had sold by the end of 2015. These reservations represent potential sales of over US$14 billion.[176][177] As of 31 March 2016[update], Tesla Motors has sold almost 125,000 electric cars worldwide since delivery of its first Tesla Roadster in 2008.[178] Tesla reported the number of net reservations totaled about 373,000 as of 15 May 2016[update], after about 8,000 customer cancellations and about 4,200 reservations canceled by the automaker because these appeared to be duplicates from speculators.[179][180]

The Hyundai Ioniq Electric was released in South Korea in July 2016, and sold over 1,000 units during its first two months in the market.[181] The Renault-Nissan Alliance achieved the milestone of 350,000 electric vehicles sold globally in August 2016, and also set an industry record of 100,000 electric vehicles sold in a single year.[182] Nissan global electric vehicle sales passed the 250,000 unit milestone also in August 2016.[182] Renault global electric vehicle sales passed the 100,000 unit milestone in early September 2016.[183] Global sales of the Tesla Model X passed the 10,000 unit mark in August 2016, with most cars delivered in the United States.[184]

Cumulative global sales of pure electric passenger cars and utility vans passed the 1 million unit milestone in September 2016.[1] Global sales of the Tesla Model S achieved the 150,000 unit milestone in November 2016, four years and five months after its introduction, and just five more months than it took the Nissan Leaf to achieve the same milestone.[186] Norway achieved the milestone of 100,000 all-electric vehicles registered in December 2016.[187] Retail deliveries of the 383 km (238 miles) Chevrolet Bolt EV began in the San Francisco Bay Area on 13 December 2016.[185] In December 2016, Nissan reported that Leaf owners worldwide achieved the milestone of 3 billion km (1.9 billion miles) driven collectively through November 2016, saving the equivalent of nearly 500 million kg (1,100 million lb) of CO

2 emissions.[188] Global Nissan Leaf sales passed 250,000 units delivered in December 2016.[189][190] The Tesla Model S was the world's best-selling plug-in electric car in 2016 for the second year running, with 50,931 units delivered globally.[174][191]

In December 2016, Norway became the first country where 5% of all registered passenger cars were plug-in electric cars.[192] When new car sales in Norway are categorised by powertrain or fuel, nine of the top ten best-selling models in 2016 were electric-drive models. The Norwegian electric-drive segment achieved a combined market share of 40.2% of new passenger car sales in 2016, consisting of 15.7% for all-electric cars, 13.4% for plug-in hybrids, and 11.2% for conventional hybris.[193] A record monthly market share for the plug-in electric passenger segment in any country was achieved in Norway in January 2017 with 37.5% of new car sales; the plug-in hybrid segment reached a 20.0% market share of new passenger cars, and the all-electric car segment had a 17.5% market share.[194] Also in January 2017, the electrified passenger car segment, consisting of plug-in hybrids, all-electric cars and conventional hybrids, for the first time ever surpassed combined sales of cars with a conventional diesel or gasoline engine, with a market share of 51.4% of new car sales that month.[194][195] For many years Norwegian electric vehicles have been subsidised by approximately 50%, and have several other benefits, such as use of bus lanes and free parking.[196] Many of these perks have been extended to 2020.[197]

In February 2017 Consumer Reports named Tesla as the top car brand in the United States and ranked it 8th among global carmakers.[199] Deliveries of the Tesla Model S passed the 200,000 unit milestone during the fourth quarter of 2017.[200] Global sales of the Nissan Leaf achieved the 300,000 unit milestone in January 2018.[201]

In September 2018, the Norwegian market share of all-electric cars reached 45.3% and plug-in hybrids 14.9%, for a combined market share of the plug-in car segment of 60.2% of new car registrations that month, becoming the world's highest-ever monthly market share for the plug-in electric passenger segment in Norway and in any country. Accounting for conventional hybrids, the electrified segment achieved an all-time record 71.5% market share in September 2018.[202][203] In October 2018, Norway became the first country where 1 in every 10 passenger cars registered is a plug-in electric vehicle.[198] Norway ended 2018 with plug-in market share of 49.1%, meaning that every second new passenger car sold in the country in 2018 was a plug-in electric. The market share for the all-electric segment was 31.2% in 2018.[204]

Tesla delivered its 100,000th Model 3 in October 2018.[207] U.S. sales of the Model 3 reached the 100,000 unit milestone in November 2018, quicker than any previous model sold in the country.[208] The Model 3 was the top-selling plug-in electric car in the U.S. for 12 consecutive months since January 2018, ending 2018 as the best-selling plug-in with an estimated all-time record of 139,782 units delivered, the first time a plug-in car sold more than 100 thousand units in a single year.[209][210][211] In 2018, for the first time in any country, an all-electric car topped annual sales of the passenger car segment. The Nissan Leaf was Norway's best selling new passenger car model in 2018.[212][213] The Tesla Model 3 listed as the world's best selling plug-in electric car in 2018.[214]

In January 2019, with 148,046 units sold since inception in the American market, the Model 3 overtook the Model S to become the all-time best selling all-electric car in the U.S.[215] Until 2019, the Nissan Leaf was the world's all-time top-selling highway legal electric car, with global sales of 450,000 units through December 2019.[205] The Tesla Model 3 ended 2019 as the world's best selling plug-in electric car for the second consecutive year, with just over 300,000 units delivered.[214][5] Also, the Model 3 topped the annual list of best selling passenger car models in the overall market in two countries, Norway and the Netherlands.[216][217]

The global stock of plug-in electric passenger cars reached 5.1 million units in December 2018, consisting of 3.3 million all-electric cars (65%) and 1.8 million plug-in hybrid cars (35%).[218][214] The global ratio between BEVs and PHEVs has been shifting towards fully electric cars, it went from 56:44 in 2012 to 60:40 in 2015, and rose from 69:31 in 2018 to 74:26 in 2019.[5][214][4] Despite the rapid growth experienced, the plug-in electric car segment represented just about 1 out of every 250 motor vehicles on the world's roads at the end of 2018.[219]

2020s

The Tesla Model 3 surpassed the Nissan Leaf in early 2020 to become the world's best selling electric car ever, with more than 500,000 total units sold by March 2020.[206] However, the Tesla Model Y is the bestselling electric vehicle in terms of yearly units.[220] Tesla also became the first auto manufacturer to produce 1 million electric cars in March 2020.[221] Global sales of the Model 3 passed the 1 million milestone in June 2021, the first electric car model to do so.[222] However, later in May 2023, the Model Y became the world's best selling vehicle in Q1.[223]

The Nissan Leaf achieved the milestone of 500,000 units sold globally in early December 2020, 10 years after its inception.[224] Combined sales of plug-in electric cars and light-duty commercial vans since 2010 achieved the 10 million unit milestone by the end of 2020. Just a year and a half later, the combined sales doubled to 20 million in June 2022.[225]

-

The Tesla Model 3 is the world's all-time best selling plug-in electric car, and became the first electric car to sell 1 million units in June 2021.[206]

-

Vietnam's VinFast VF e34

-

VinFast VinBus

Electric bicycle

The principal manufacturer of e-bikes globally is China, with 2009 seeing the manufacturing of 22.2 million units. In the world Geoby is the leading manufacturers of E-bikes. Pedego is the best selling in the U.S. China accounts for nearly 92% of the market worldwide. In China the number of electric bicycles on the road was 120 million in 2010. Jiangsu Yadea, an electric bicycle producer of renown in China, leads the ranking of China National Light Industry Council (CNLIC) electric bicycle industry for three years. It retains capacity of nearly 6 million electric bicycles a year.

In 1997, Charger Electric Bicycle was the first U.S. company to come out with a pedelec.

First models of electric bicycles appeared in late 19th century. US Patent office registered several e-bike patents since 1895 to 1899 (Ogden Bolton patented battery-powered bicycle in 1895, Hosea W. Libbey patented bicycle with double electric motor in 1897 and John Schnepf patented electric motor with roller wheel).

Timeline of milestones

| Date | Timeline of electric vehicle milestones |

|---|---|

| 1875 | World's first electric tram line operated in Sestroretsk near Saint Petersburg, Russia, invented and tested by Fyodor Pirotsky.[226][227] |

| 1881 | World's first commercially successful electric tram, the Gross-Lichterfelde tramway in Lichterfelde near Berlin in Germany built by Werner von Siemens who contacted Pirotsky. It initially drew current from the rails, with overhead wire being installed in 1883. |

| 1882 | The trolleybus dates back to 29 April 1882, when Dr. Ernst Werner Siemens demonstrated his "Elektromote" in a Berlin suburb. This experiment continued until 13 June 1882 |

| 1883 | Mödling and Hinterbrühl Tram, Vienna, Austria, first electric tram powered by overhead wire. |

| 1884 | Thomas Parker built an electric car in Wolverhampton using his own specially designed high-capacity rechargeable batteries. |

| Dec 1996 | Launch of the limited production General Motors EV1[228][229] |

| 1998 | Launch of Nissan Altra EV, becoming the first highway legal electric car to use lithium-ion batteries[73][74] |

| Jul 2009 | Launch of the Mitsubishi i-MiEV, the first modern highway legal series production electric car[101] |

| Dec 2010 | Nissan Leaf and Chevrolet Volt deliveries began[230] |

| 2011 | The Nissan Leaf passed the Mitsubishi i MiEV as the world's all-time best selling all-electric car[129] |

| Jun 2012 | Launch of the Tesla Model S[231] |

| Mar 2014 | 1% of all cars in use in Norway are plug-ins[232] |

| Sep 2015 | Cumulative global plug-in sales passed 1 million units.[233] |

| Nov 2016 | Global all-electric car/van sales passed 1 million.[1] |

| Dec 2016 | Cumulative global plug-in sales passed 2 million units[234] |

| 5% of passenger cars on Norwegian roads are plug-ins[192] | |

| Early 2017 |

1 millionth domestic new energy car sold in China[235][236] |

| Jul 2017 | Launch of the Tesla Model 3[237] |

| Nov 2017 | Cumulative global plug-in sales passed 3 million units[218] |

| Dec 2017 | Annual global sales passed the 1 million unit mark[238] |

| 5% of all cars in use in Norway are all-electric.[239] | |

| Annual global market share passed 1% for the first time[238] | |

| First half 2018 |

1 millionth plug-in electric car sold in Europe[240] |

| Sep 2018 | 1 millionth plug-in electric car sold in the U.S.[241] |

| 2 millionth new energy vehicle sold in China[242] (includes heavy-duty commercial vehicles) | |

| Oct 2018 | 10% of passenger cars on Norwegian roads are plug-ins[243] |

| Nov 2018 | 500,000th plug-in car sold in California[244] |

| Dec 2018 | Annual global sales passed the 2 million unit mark[214][245] |

| Tesla Model 3 becomes first plug-in to exceed 100,000 sales in a single year[246] | |

| Dec 2019 | One out of two new passenger cars registered in Norway in 2019 was a plug-in electric car[247] |

| Early 2020 |

The Tesla Model 3 surpassed the Nissan Leaf as the world's best selling plug-in electric car in history[206] |

| Mar 2020 | The Tesla Model 3 is the first electric car to sell more than 500,000 units since inception.[206] |

| Tesla, Inc. becomes the first auto manufacturer to produce 1 million electric cars[221] | |

| Apr 2020 | 10% of all cars on the road in Norway are all-electric[248] |

| Dec 2020 | Nissan Leaf global sales reached 500,000 units.[224] |

| Cumulative global plug-in sales passed the 10 million unit milestone [3] | |

| The Norwegian plug-in car segment achieved a record annual market share of 74.7% of new car sales.[249] | |

| Over 15% of all cars on Norwegian roads are plug-in electric.[250] | |

| June 2021 | Tesla Model 3 global sales passed 1,000,000 units.[251] |

| May 2022 | Cumulative global plug-in sales passed the 20 million unit milestone[225] |

| January 2023 | EVs surpass 10% in global market share[252] |

| May 2023 | Tesla Model Y becomes the world's best selling vehicle[223] |

Notable production vehicles

Selected list of battery electric vehicles include (in chronological order):[253][254]

| Name | Production years | Number produced | Range | Notability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker Electric | 1899–1915 | 80 km (50 miles) | One of the first electric cars. Largest electric automaker in the world, as of 1906. | |

| Studebaker Electric | 1902–1912 | 1,841 | 30–80 miles | One of the first electric cars. |

| Detroit Electric | 1907–1939 | 13,000[255] | 130 km (80 miles) | Over 13,000 manufactured, making it one of the most successful early electric vehicles. |

| Henney Kilowatt | 1958–1960 | <100 | First mass production electric car since they fell out of favour in the early 1900s. | |

| Sebring-Vanguard Citicar | 1974–1982 | 4,444 including variants[256] |

Approximately 65 km (40 miles) |

Most popular electric car of its time, post-war. |

| General Motors EV1 | 1996–2003 | 1,117 | 255 km (160 miles) | First purpose-designed electric vehicle of the modern era from a major automaker and the first GM car designed to be an electric vehicle from the outset. |

| Honda EV Plus | 1997–1999 | ~300 | 130–175 km (80–110 miles) | First known vehicle from a major automaker to eschew the use of lead-acid batteries in favour of NiMH. |

| Toyota RAV4 EV | 1997–2002 | 1,900[257] | 140 km (87 miles) | First electric vehicle to be publicly sold by Toyota |

| REVAi | 2001–2012 | 4,000+[258] | 80 km (50 miles) | |

| Tesla Roadster | 2008–2012 | 2,500 | 355 km (220 miles) | First vehicle by Tesla, Inc. |

| Mitsubishi i MiEV (Peugeot iOn/Citroën C-Zero) |

2009– | 50,000 (2015)[259] | 160 km (100 miles) (Japanese cycle) 100 km (62 miles) (EPA cycle) |

First significantly popular production electric vehicle (over 50,000 sold). |

| Nissan Leaf | 2010– | 470,000 (2020)[260] | 175 km (109 miles) (New European Driving Cycle) | Surpassed the Mitsubishi i-MiEV to become the most successful electric vehicle until the Tesla Model 3. Over 500,000 sold. |

| BYD F3DM | 2010-2013 | 3,284 | 97 km (60 miles) | First mass-produced plug-in hybrid automobile. |

| Renault Kangoo Z.E. | 2011– | 50,000 (2020)[261][262] | As of December 2019, the top-selling all-electric light commercial vehicle in Europe. | |

| Tesla Model S | 2012– | 200,000 (2017)[200] | 560 km (348 miles) Performance mode

402 miles (647 km) Long Range Plus [263] |

First clean-slate design from Tesla, Inc. |

| Renault Zoe | 2013– | Since 2020, Europe's all-time best selling plug-in electric car. | ||

| BMW i3 | 2013– | 165,000 (2020)[264] | 130 to 160 km (80 to 100 miles)[265] | First purpose-designed electric car from BMW. |

| Chevrolet Bolt | 2017– | 51,600 (2018)[266] | 238 miles (383 km)[267] | |

| Tesla Model 3[268] | 2017– | More than 500,000 by March 2020[206] |

355 km (220 miles) Standard version,

500 km (310 miles) Long Range version |

Most successful electric car worldwide, as of 2020. |

See also

- History of the automobile

- History of plug-in hybrids

- History of electric motorcycles and scooters

- List of production battery electric vehicles

- Country specific

- Electric car use by country

- Plug-in electric vehicles in Japan

- Plug-in electric vehicles in the Netherlands

- Plug-in electric vehicles in Norway

- Plug-in electric vehicles in the United Kingdom

- Plug-in electric vehicles in the United States

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Shahan, Zachary (2016-11-22). "1 Million Pure EVs Worldwide: EV Revolution Begins!". Clean Technica. https://cleantechnica.com/2016/11/22/1-million-ev-revolution-begins/.

- ↑ "Global EV Outlook 2020: Entering the decade of electric drive?". International Energy Agency (IEA), Clean Energy Ministerial, and Electric Vehicles Initiative (EVI). June 2020. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2020. See Statistical annex, pp. 247–252 (See Tables A.1 and A.12). The global stock of plug-in electric passenger vehicles totaled 7.2 million cars at the end of 2019, of which, 47% were on the road in China. The stock of plug-in cars consist of 4.8 million battery electric cars (66.6%) and 2.4 million plug-in hybrids (33.3%). In addition, the stock of light commercial plug-in electric vehicles in use totaled 378 thousand units in 2019, and about half a million electric buses were in circulation, most of which are in China.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Irle, Roland (19 January 2021). "Global Plug-in Vehicle Sales Reached over 3,2 Million in 2020". https://www.ev-volumes.com/news/86364/. Plug-in sales totaled 3.24 million in 2020, up from 2.26 million in 2019. Europe, with nearly 1.4 million units surpassed China as the largest EV market for the first time since 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hertzke, Patrick; Müller, Nicolai; Schenk, Stephanie; Wu, Ting (May 2018). "The global electric-vehicle market is amped up and on the rise". McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/the-global-electric-vehicle-market-is-amped-up-and-on-the-rise. See Exhibit 1: Global electric-vehicle sales, 2010-17.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Jose, Pontes (2020-01-31). "Global Top 20 - December 2019". EVSales.com. http://ev-sales.blogspot.com/2020/01/global-top-20-december-2019.html. "Global sales totaled 2,209,831 plug-in passenger cars in 2019, with a BEV to PHEV ratio of 74:26, and a global market share of 2.5%. The world's top selling plug-in car was the Tesla Model 3 with 300,075 units delivered, and Tesla was the top selling manufacturer of plug-in passenger cars in 2019 with 367,820 units, followed by BYD with 229,506."

- ↑ Kane, Mark (4 October 2020). "See The Best Selling Battery Electric Cars Of All-Time Here". https://insideevs.com/news/447165/see-best-selling-battery-electric-cars/.

- ↑ Block, S.S. (2015). Benjamin Franklin, Genius of Kites, Flights and Voting Rights. McFarland, Incorporated, Publishers. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-7864-8024-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=_SpzBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA84. Retrieved 2023-04-07.

- ↑ Eisen, J. (2001). Suppressed Inventions and Other Discoveries: Revealing the World's Greatest Secrets of Science and Medicine. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-399-52735-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=caMNee9ybUQC&pg=PA499. Retrieved 2023-04-07.

- ↑ Barber, H.L. (1917). Story of the Automobile: Its History and Development from 1760 to 1917, with an Analysis of the Standing and Prospects of the Automobile Industry. A. J. Munson & Company. p. 13. https://books.google.com/books?id=qyUtJjqXQ_YC&pg=PA13. Retrieved 2023-04-07.

- ↑ Guarnieri, Massimo (2012). "Looking back to electric cars". HISTory of ELectro-technology CONference (HISTELCON). pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/HISTELCON.2012.6487583. ISBN 9781467330787. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/6487583. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Bellis, M. (2006), "The Early Years", The History of Electric Vehicles, About.com, http://inventors.about.com/library/weekly/aacarselectrica.htm, retrieved 6 July 2006

- ↑ "The world's first electric car" (in nl). University of Groningen Museum. 8 October 2021. https://www.rug.nl/museum/collections/collection-stories/wagentje-van-stratingh.

- ↑ Today in Technology History: July 6, The Center for the Study of Technology and Science, http://www.tecsoc.org/pubs/history/2001/jul6.htm, retrieved 2009-07-14

- ↑ Day, Lance; McNeil, Ian (1966). "Davidson, Robert". Biographical dictionary of the history of technology. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06042-4. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780415060424.

- ↑ Gordon, William (1910). "The Underground Electric". Our Home Railways. 2. London: Frederick Warne. p. 156.

- ↑ Renzo Pocaterra, Treni, De Agostini, 2003

- ↑ Armstrong Moore, Elizabeth (10 February 2009), "As electric cars gain currency, Oregon charges ahead", Christian Science Monitor, http://features.csmonitor.com/environment/2009/02/10/as-electric-cars-gain-currency-oregon-charges-ahead/, retrieved 2009-04-24

- ↑ "Electric Traction". September 2010. http://mikes.railhistory.railfan.net/r066.html.

- ↑ Johnston, Ben (September 2010). "Battery Rail Vehicles". http://railknowledgebank.com/Presto/content/GetDoc.axd?ctID=MTk4MTRjNDUtNWQ0My00OTBmLTllYWUtZWFjM2U2OTE0ZDY3&rID=NzA=&pID=Nzkx&attchmnt=True&uSesDM=False&rIdx=MjUyOA==&rCFU=.

- ↑ "Planté Battery". National High Magnetic Field Laboratory. http://www.magnet.fsu.edu/education/tutorials/museum/plantebattery.html.

- ↑ "Development of the Motor Car and Bicycle". TravelSmart Teacher Resource Kit (Government of Australia). 2003. http://www.travelsmart.gov.au/teachers/teachers6.html. Retrieved 2009-04-24.

- ↑ Timeline: Life & Death of the Electric Car, NOW on PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 9 June 2006, https://www.pbs.org/now/shows/223/electric-car-timeline.html, retrieved 2009-04-24

- ↑ Wakefield, Ernest H. (1994), History of the Electric Automobile, Society of Automotive Engineers, pp. 2–3, ISBN 1-56091-299-5

- ↑ Wakefield, Ernest Henry (1993), History of the Electric Automobile, USA: Society of Automobile Engineers, pp. 540

- ↑ Desmond, Kevin (2000). A Century of Outboard Racing. Van de Velde Maritime. ISBN 978-0760310472.

- ↑ Communication made by Trouvé to the Académie des Sciences de Paris, 1881

- ↑ "World's first electric car built by Victorian inventor in 1884". The Daily Telegraph (London). 2009-04-24. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/howaboutthat/5212278/Worlds-first-electric-car-built-by-Victorian-inventor-in-1884.html.

- ↑ Fuller, John (2009-04-09). "What is the history of electric cars?". auto.howstuffworks.com. http://auto.howstuffworks.com/fuel-efficiency/hybrid-technology/history-of-electric-cars1.htm.

- ↑ "Electric Vehicles History Part III". http://www.electricvehiclesnews.com/History/historyearlyIII.htm.

- ↑ Schrader, Halwart (2002) (in de). Deutsche Autos 1885 - 1920. Stuttgart: Motorbuch-Verlag. p. 182. ISBN 9783613022119.

- ↑ Boyle, David (2018). 30-Second Great Inventions. Ivy Press. pp. 62. ISBN 9781782406846.

- ↑ Denton, Tom (2016). Electric and Hybrid Vehicles. Routledge. p. 6. ISBN 9781317552512.

- ↑ "Elektroauto in Coburg erfunden" (in de). Neue Presse Coburg. Germany. 2011-01-12. https://www.np-coburg.de/lokal/coburg/coburg/Elektroauto-in-Coburg-erfunden;art83423,1491254.

- ↑ Cub Scout Car Show, January 2008, http://www.macscouter.com/CubScouts/PowWow07/SCCC_2007/CubScoutThemes/Jan_2008.pdf, retrieved 2009-04-12

- ↑ "1896 Riker Electric Tricycle". The Henry Ford. https://www.thehenryford.org/collections-and-research/digital-collections/artifact/274188/.

- ↑ Says, Alan Brown. "The Surprisingly Old Story of London's First Ever Electric Taxi" (in en-GB). https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/the-surprisingly-old-story-of-londons-first-ever-electric-taxi/.

- ↑ "History of the Licensed London Taxi". http://www.london-taxi-cabs.com/information/history-of-the-licensed-london-taxi.

- ↑ "Hailing the History of New York's Yellow Cabs". https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=11804573.

- ↑ "Car Companies". Early Electric. http://www.earlyelectric.com/carcompanies.html.

- ↑ Taalbi, Josef; Nielsen, Hana (2021). "The role of energy infrastructure in shaping early adoption of electric and gasoline cars" (in en). Nature Energy 6 (10): 970–976. doi:10.1038/s41560-021-00898-3. ISSN 2058-7546. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41560-021-00898-3.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Automobile, https://www.britannica.com/technology/automobile/Early-electric-automobiles, retrieved 18 July 2009

- ↑ Scharff, Virginia (1992). Taking the Wheel: Women and the Coming of the Motor Age. Univ. New Mexico Press.

- ↑ Marçal, Katrine (5 Nov 2021). "Ladies only: Why men snubbed the original electric car". https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-ladies-only-why-men-snubbed-the-original-electric-car/.

- ↑ Kimes, Beverly (1996). Standard Catalog of American Cars 1805–1942. Krause Publications. p. 1591. ISBN 0-87341-478-0.

- ↑ "Ford Focus Electric Reviews - Ford Focus Electric Price, Photos, and Specs - Car and Driver". http://www.caranddriver.com/ford/focus-electric/specs.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Kirsch, David A. (2000). The Electric Vehicle and the Burden of History. New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Rutgers University Press. pp. 153–162. ISBN 0-8135-2809-7. https://archive.org/details/electricvehicleb0000kirs.

- ↑ "Electric Delivery and Trucking During the Blizzard". The New York Times: pp. 6. 1914-02-18. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/58164944/electric-delivery-and-trucking-during/.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "75 General Vehicles Electric Trucks". The New York Times: p. 6. 1914-02-18. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/58165046/75-general-vehicles-electric-trucks/.

- ↑ "Lord & Taylor Open Fifth Avenue Store". The New York Times: p. 6. 1914-02-25. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/58165407/lord-taylor-open-fifth-avenue-store/.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Matthe, Roland; Eberle, Ulrich (2014-01-01). "The Voltec System - Energy Storage and Electric Propulsion". https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262004450.

- ↑ McMahon, D. (13 November 2009). "Some EV History / History of Electric Cars and Other Vehicles". Econogics. http://www.econogics.com/ev/evhistry.htm.

- ↑ "1984". Yale History. http://www.yale.com/ygl_history.asp?language=English.

- ↑ "Escaping Lock-in: the Case of the Electric Vehicle". http://www.cgl.uwaterloo.ca/~racowan/escape.html.

- ↑ "Lektro has been making electric vehicles since 1945". Lektro. http://www.lektro.com/about_history.asp. Chapter: Lektro history.

- ↑ Schiffer, Michael Brian (17 March 2003). Taking Charge: The Electric Automobile in America. Smithsonian. ISBN 978-1-58834-076-4.

- ↑ Appel, Tom (5 January 2018). "What Was The Henney Kilowatt?". The Daily Drive. https://blog.consumerguide.com/what-was-the-henney-kilowatt/.

- ↑ Schreiber, Ronnie (3 May 2019). "The Henney Kilowatt: Tesla Model 3's long lost ancestor". Hagerty. https://www.hagerty.com/media/car-profiles/henney-kilowatt-tesla-model-3-ancestor/.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Rearview Mirror". Ward's AutoWorld. 1 April 2000. http://wardsautoworld.com/ar/auto_rearview_mirror_13/index.html. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ↑ Russell, Roger. "Sonotone History: Tubes, Hi-Fi Electronics, Tape heads and Nicad Batteries". Sonotone Corporation History. http://www.roger-russell.com/sonopg/sononst.htm.

- ↑ Carr, Richard (1 July 1966). "In search of the town car". Design (Council of Industrial Design) (211): 29–37.

- ↑ Valdes-Dapena, Peter (7 April 2009). "GM's long road back to electric cars". CNN. https://money.cnn.com/galleries/2008/autos/0809/gallery.gm_electric_cars/3.html.

- ↑ Westbrook, Michael Hereward (2001). The Electric Car. Institute of Engineering & Technology. ISBN 0-85296-013-1.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Goodstein, Judith (2004). "Godfather of the Hybrid". Engineering & Science (California Institute of Technology) LXVII (3). https://calteches.library.caltech.edu/4118/1/Hybrid.pdf. Retrieved 9 July 2022.

- ↑ Florea, Ciprian (11 March 2022). "Remembering the AMC Amitron, the EV Concept That Looks Like a Mini Tesla Cybertruck". https://www.autoevolution.com/news/remembering-the-amc-amitron-the-ev-concept-that-looks-like-a-mini-tesla-cybertruck-183716.html.

- ↑ Randerson, James (July 2008). "Who stopped the future?". Wallpaper (IPC Media) (112): 104. ISSN 1364-4475. OCLC 948263254. "'The big problem was that it had no market,' says Woordward. 'Globa warming hadn't been invented then'".

- ↑ Thompson, Cadie (2 July 2017). "How the electric car became the future of transportation". Business Insider (US). https://www.businessinsider.com/electric-car-history-2017-5.

- ↑ Abuelsamid, Sam (5 November 2008). "eBay find of the day: 1980 Lectric Leopard". https://www.autoblog.com/2008/11/05/ebay-find-of-the-day-1980-lectric-leopard-w-video/.

- ↑ Edelstein, Stephen (21 January 2014). "Rare 1980 Ford Fairmont EVA Electric Conversion For Sale". Green Car Reports (US). https://www.greencarreports.com/news/1089781_rare-1980-ford-fairmont-eva-electric-conversion-for-sale.

- ↑ Richardson, R.A.; Yarger, E.J.; Cole, G.H. (1 April 1996). Dynamometer testing of the U.S. Electricar Geo Prizm conversion electric vehicle (Technical report). US: U.S. Department of Energy Office of Scientific and Technical Information. doi:10.2172/236257. OSTI 236257. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ↑ McCausland, Evan (13 August 2008). "1994 Solectria E10 and 1997 Chevrolet S10 Electric Pickups". Automobile magazine (US). https://www.automobilemag.com/news/1994-solectria-e10-and-1997-chevrolet-s10-electric-pickups-134812/.

- ↑ Sperling, Daniel and Deborah Gordon (2009), Two billion cars: driving toward sustainability, Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 24 and 189–191, ISBN 978-0-19-537664-7

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 72.2 72.3 Who Killed the Electric Car? Directed by Chris Paine, Distributed by Sony Pictures Classics

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 "California Commuter". EV World. 2001-01-31. http://www.evworld.com/archives/testdrives/altra.html.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 The Nissan Altra EV - Nissan Launching Electrick Minivan

- ↑ "California's Clean Cars Program Under Attack". https://www.nrdc.org/media/2003/030213.

- ↑ Adams, Noel (2001-12-02). "Why is GM Crushing Their EV-1s?". Electrifying Times. http://www.electrifyingtimes.com/ev1crush.html.

- ↑ King, Danny (20 June 2011). "Neighborhood Electric Vehicle Sales To Climb". Edmunds Auto Observer. http://www.autoobserver.com/2011/06/neighborhood-electric-vehicle-sales-to-climb.html.

- ↑ Saranow, Jennifer (27 July 2006). "The Electric Car Gets Some Muscle". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. http://www.post-gazette.com/pg/06208/709068-185.stm.

- ↑ "Polaris GEM Introduces 2015 Models". 2014-07-24. https://www.wsj.com/article/PR-CO-20140724-915574.html.

- ↑ Hurst and Clint Wheelock, Dave (2011). "Executive Summary: Neighborhood Electric Vehicles – Low Speed Electric Vehicles for Consumer and Fleet Markets". Pike Research. http://www.pikeresearch.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/NEV-11-Executive-Summary.pdf.

- ↑ "Historien bak Buddy" (in no). Norway. http://www.puremobility.com/no/om-pure-mobility.

- ↑ "Think Begins Production of New TH!NK City EV". Green Car Congress. 2007-12-02. http://www.greencarcongress.com/2007/12/think-begins-pr.html.

- ↑ Montavalli, Jim (2009-12-11). "Think Restarts Production in Finland". The New York Times. http://wheels.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/12/11/think-restarts-production-in-finland/?scp=1&sq=Think%20Restarts%20Production%20in%20Finland&st=cse.

- ↑ "THINK Begins EV Sales in Finland". Green Car Congress. 11 September 2010. http://www.greencarcongress.com/2010/09/thinkev-20100911.html#more.

- ↑ Loveday, Eric (2010-09-13). "Think kicks off sales of City electric vehicle in Finland". AutoblogGreen. http://green.autoblog.com/2010/09/13/think-kicks-off-sales-of-city-electric-vehicle-in-finland/.

- ↑ Bolduc, Douglas A. (2011-06-22). "Norwegian EV maker Think files for bankruptcy". Automotive News. http://www.autonews.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20110622/COPY01/306229798/1193.

- ↑ Doggett, Scott (2011-03-30). "Think Announces $36,495 MSRP for City EV". http://blogs.edmunds.com/greencaradvisor/2011/03/think-announces-36495-msrp-for-city-ev.html.

- ↑ Xueqing, Jiang (2014-01-11). "New-energy vehicles 'turning the corner'". China Daily. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/motoring/2014-01/11/content_17229981.htm.

- ↑ Reardon, William A. (1973). The energy and resource conservation aspects of electric vehicle utilization for the City of Seattle. Richland, WA: Battelle Pacific Northwest Laboratories. pp. 28–29.

- ↑ "We have begun regular production of the Tesla Roadster". Tesla Motors. 2008-03-17. http://www.teslamotors.com/blog2/?p=57.

- ↑ Shahan, Zachary (2015-04-26). "Electric Car Evolution". Clean Technica. https://cleantechnica.com/2015/04/26/electric-car-history/. 2008: The Tesla Roadster becomes the first production electric vehicle to use lithium-ion battery cells as well as the first production electric vehicle to have a range of over 200 miles on a single charge.

- ↑ "SEC Form 10-K for Fiscal Year Ended Dec 31, 2012, Commission File Number: 001-34756, Tesla Motors, Inc.". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2016-02-06. http://ir.teslamotors.com/secfiling.cfm?filingid=1193125-13-96241&cik=. "As of December 31, 2012, we had delivered approximately 2,450 Tesla Roadsters to customers in over 30 countries."

- ↑ Woodyard, Chris (2011-08-03). "Tesla boasts about electric car deliveries, plans for sedan". USA Today. http://content.usatoday.com/communities/driveon/post/2011/08/tesla-boasts-about-electric-car-deliveries-plans-for-sedan/1.

- ↑ Garthwaite, Josie (2011-05-06). "Tesla Prepares for a Gap as Roadster Winds Down". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/08/automobiles/08TESLA.html?_r=1&emc=eta1.

- ↑ Dillow, Clay (2011-06-24). "Farewell Roadster: Tesla Will Stop Taking Orders for its Iconic EV in Two Months". Popular Science (US). http://www.popsci.com/cars/article/2011-06/farewell-roadster-tesla-will-stop-taking-orders-its-iconic-ev-two-months.

- ↑ Valdes-Dapena, Peter (2011-06-22). "Tesla Roadster reaches the end of the line". CNN Money (US). https://money.cnn.com/2011/06/21/autos/tesla_roadster_selling_out/index.htm.

- ↑ King, Danny (2012-01-11). "Tesla continues Roadster sales with tweaks in Europe, Asia and Australia". Autoblog Green. http://green.autoblog.com/2012/01/11/tesla-continues-roadster-sales-in-europe-asia-and-australia/#continued.

- ↑ Gordon-Bloomfield, Nikki (2012-01-11). "Tesla Updates Roadster For 2012. There's Just One Catch...". Green Car Reports. http://www.greencarreports.com/news/1071608_tesla-updates-roadster-for-2012-theres-just-one-catch.

- ↑ "Mitsubishi Motors Begins Production of i-MiEV; Targeting 1,400 Units in Fiscal 2009". Green Car Congress. 5 June 2009. http://www.greencarcongress.com/2009/06/imiev-20090605.html.

- ↑ Kageyama, Yuri (2010-03-31). "Japanese Start Buying Affordable Electric Cars". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/businesstechnology/2011495208_apasjapanelectriccar.html?syndication=rss.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Kim, Chang-Ran (2010-03-30). "Mitsubishi Motors lowers price of electric i-MiEV". Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTOE62T09V20100330.

- ↑ "Mitsubishi Begins Sales of i-MiEV to Individuals in Hong Kong; First Individual Sales Outside of Japan". Green Car Congress. 2010-05-20. http://www.greencarcongress.com/2010/05/hksar-20100520.html#more.

- ↑ "Mitsubishi Motors to Begin Shipping i-MiEV to Australia in July; 2nd Market Outside Japan". Green Car Congress. 2010-06-02. http://www.greencarcongress.com/2010/06/imiev-20100602.html#more.

- ↑ "The i-MiEV goes on sale in 15 European countries; near-term plan to boost that to 19". GreenCarCongress. 2011-01-14. http://www.greencarcongress.com/2011/01/imiev-20110114.html#more.

- ↑ Halvorson, Bengt (2011-10-04). "2012 Mitsubishi i: First Drive, U.S.-Spec MiEV". Green Car Reports. http://www.greencarreports.com/news/1066863_2012-mitsubishi-i-first-drive-u-s--spec-miev.

- ↑ "Mitsubishi To Launch Its Electric Car First in Costa Rica". InsideCostaRica. 2010-12-27. http://insidecostarica.com/dailynews/2010/december/27/costarica10122704.htm.

- ↑ Ibarra, Alejandro Marimán (2011-05-04). "Mitsubishi i-MIEV: Lanzado oficialmente en Chile" (in es). Yahoo Chile. http://cl.noticias.autocosmos.yahoo.net/2011/05/04/mitsubishi-i-miev-lanzado-oficialmente-en-chile.

- ↑ Woodyard, Chris (2011-12-08). "Mitsubishi delivers its first 'i' electric car". USA Today. http://content.usatoday.com/communities/driveon/post/2011/12/mitsubishi-delivers-its-first-i-electric-car/1.

- ↑ Mitsubishi Motors North America (2011-12-12). "Mitsubishi Motors, Governor of Hawaii and Cutter Mitsubishi Hand Over Keys to First 2012 Mitsubishi i-MiEV Retail Customer". ABC Action News (Press release). Archived from the original on 2012-07-19. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- ↑ Blanco, Sebastian (2011-06-08). "Mitsubishi sets Canadian i-MiEV price at $32,998". AutoblogGreen. http://green.autoblog.com/2011/06/08/mitsubishi-sets-canadian-i-miev-price-at-32-998/.

- ↑ Ingram, Antony (2013-01-24). "Mitsubishi i-MiEV Electric Cars Recalled To Fix Braking Problem". Green Car Reports. http://www.greencarreports.com/news/1081892_mitsubishi-i-miev-electric-cars-recalled-to-fix-braking-problem.

- ↑ Friend, Tad (2009-01-07). "Elon Musk and electric cars". The New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2009/08/24/090824fa_fact_friend. Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ↑ "Global EV Outlook 2023 / Trends in electric light-duty vehicles". International Energy Agency. April 2023. https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2023/trends-in-electric-light-duty-vehicles.

- ↑ Doggett, Scott (2010-12-11). "First Production Nissan Leaf Electric Vehicle Delivered to Customer". Edmunds.com. http://www.insideline.com/nissan/leaf/2011/first-production-nissan-leaf-electric-vehicle-delivered-to-customer.html.

- ↑ "Nissan Rolls Out Leaf Electric Car in Japan". Associated Press. 3 December 2010. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=131771329.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 "Nissan LEAF Smashes 50,000 Global Sales Milestone" (Press release). Nissan Media Room. 2013-02-14. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "The Renault Fluence ZE". Better Place. 2010-10-22. http://www.betterplace.com/the-company-multimedia-photos/index/id/72157623854339020.

- ↑ Udasin, Sharon (2011-03-24). "Better Place launches 1st Israeli battery-switching station". The Jerusalem Post. http://www.jpost.com/Sci-Tech/Article.aspx?id=213562.

- ↑ "Better Place Delivers For Demanding Amsterdam Taxi Drivers". Better Place. http://www.betterplace.com/the-company/press-room/Better-Place-Delivers-for-Demanding-Amsterdam-Taxi-Drivers.

- ↑ McCowen, David (2013-02-18). "The rise and fall of Better Place". Drive.com.au. http://news.drive.com.au/drive/motor-news/the-rise-and-fall-of-better-place-20130218-2emmn.html.

- ↑ Beissmann, Tim (2012-12-13). "Renault Fluence Z.E. launch delayed due to infrastructure hold-ups". Car Advice. http://www.caradvice.com.au/205154/renault-fluence-z-e-launch-delayed-due-infrastructure-hold-ups/.

- ↑ "Better Place winding down ops in North America and Australia, to focus on Denmark and Israel". Green Car Congress. 2013-04-17. http://www.greencarcongress.com/2013/02/bp-20130207.html.

- ↑ Voelcker, John (2013-05-26). "Better Place Electric-Car Service Files For Bankruptcy". Green Car Reports. http://www.greencarreports.com/news/1084406_better-place-electric-car-service-files-for-bankruptcy.

- ↑ Kershner, Isabel (2013-05-26). "Israeli Venture Meant to Serve Electric Cars Is Ending Its Run". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/27/business/global/israeli-electric-car-company-files-for-liquidation.html?_r=0.

- ↑ Elis, Niv (2013-05-26). "Death of Better Place: Electric car co. to dissolve". The Jerusalem Post. http://www.jpost.com/Business/Business-News/Death-of-Better-Place-Electric-car-co-to-dissolve-314380.

- ↑ "First Pure-Electric Vehicle now available for Consumers in China". BYD Company. 2011-10-27. http://www.bydenergy.com/bydenergy/energy/News%20Center/News/78.html.

- ↑ Lord, Richard (2011-12-05). "Autolib' electric car sharing service launches in Paris, France". Sustainable Guernsey. http://www.sustainableguernsey.info/blog/2011/12/autolib-electric-car-sharing-service-launches-in-paris-france/.

- ↑ Lepsch, Laurent (2012-10-08). "Louez une Bluecarpour 500 € par mois" (in fr). Auto News. http://www.autonews.fr/dossiers/votre-quotidien/90768-bollore-blucear-paris-location.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 Guinness World Records (2012). "Best-selling electric car". Guinness World Records. http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/records-10000/best-selling-electric-car/.

- ↑ Boudreau, John (2012-06-22). "In a Silicon Valley milestone, Tesla Motors begins delivering Model S electric cars". San Jose Mercury News. http://www.mercurynews.com/business/ci_20919722/silicon-valley-milestone-tesla-motors-begins-delivering-model?refresh=no.

- ↑ Ingram, Antony (2013-08-07). "First 2013 Tesla Model S Delivered Outside North America--In Oslo". Green Car Reports. http://www.greencarreports.com/news/1086101_first-2013-tesla-model-s-delivered-outside-north-america--in-oslo.

- ↑ Makinen, Julie (2014-04-22). "Tesla delivers its first electric cars in China; delays upset some". Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/business/autos/highway1/la-fi-hy-tesla-elon-musk-china-20140422,0,4201103.story#axzz2zd58LPWF.

- ↑ Blanco, Sebastian (2014-11-05). "Tesla Model X delayed, again, but Musk says Model S demand remains high". Autoblog Green. http://green.autoblog.com/2014/11/05/tesla-model-x-delayed-again/.

- ↑ "UC Irvine's car-sharing program charges ahead" (Press release). University of California, Irvine. 2013-03-21. Retrieved 2013-03-28.

- ↑ "Electric Car Maker Files for Bankruptcy Protection". The New York Times. Reuters. 2013-05-01. https://www.nytimes.com/2013/05/02/business/global/02iht-coda02.html?ref=automobiles&_r=0.