Oil well

Topic: Engineering

From HandWiki - Reading time: 21 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 21 min

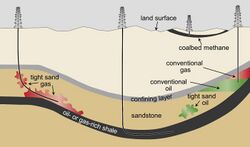

An oil well is a drillhole boring in Earth that is designed to bring petroleum oil hydrocarbons to the surface. Usually some natural gas is released as associated petroleum gas along with the oil. A well that is designed to produce only gas may be termed a gas well. Wells are created by drilling down into an oil or gas reserve and if necessary equipped with extraction devices such as pumpjacks. Creating the wells can be an expensive process, costing at least hundreds of thousands of dollars, and costing much more when in difficult-to-access locations, e.g., offshore. The process of modern drilling for wells first started in the 19th century but was made more efficient with advances to oil drilling rigs and technology during the 20th century.

Wells are frequently sold or exchanged between different oil and gas companies as an asset – in large part because during a drop in the price of oil and gas, a well may be unproductive, but if prices rise, even low-production wells may be economically valuable. Moreover, new methods, such as hydraulic fracturing (a process of injecting gas or liquid to force more oil or natural gas production) have made some wells viable. However, peak oil and climate policy surrounding fossil fuels have made fewer of these wells and costly techniques viable.

However, neglected or poorly maintained wellheads present environmental issues: they may leak methane or other toxic substances into local air, water and soil systems. This pollution often becomes worse when wells are abandoned or orphaned – i.e., where a well is no longer economically viable, so are no longer maintained by their (former) owners. A 2020 estimate by Reuters suggested that there were at least 29 million abandoned wells internationally, creating a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions worsening climate change.[1][2]

History

The earliest known oil wells were drilled in China in 347 CE. These wells had depths of up to about 240 metres (790 ft) and were drilled using bits attached to bamboo poles.[3] The oil was burned to evaporate brine producing salt. By the 10th century, extensive bamboo pipelines connected oil wells with salt springs. The ancient records of China and Japan are said to contain many allusions to the use of natural gas for lighting and heating. Petroleum was known as burning water in Japan in the 7th century.[4][5]

According to Kasem Ajram, petroleum was distilled by the Persian alchemist Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi (Rhazes) in the 9th century, producing chemicals such as kerosene in the alembic (al-ambiq),[6][7] and which was mainly used for kerosene lamps.[8] Arab and Persian chemists also distilled crude oil in order to produce flammable products for military purposes. Through Islamic Spain, distillation became available in Western Europe by the 12th century.[9]

Some sources claim that from the 9th century, oil fields were exploited in the area around modern Baku, Azerbaijan, to produce naphtha for the petroleum industry. These places were described by Marco Polo in the 13th century, who described the output of those oil wells as hundreds of shiploads. When Marco Polo in 1264 visited Baku, on the shores of the Caspian Sea, he saw oil being collected from seeps. He wrote that "on the confines toward Geirgine there is a fountain from which oil springs in great abundance, in as much as a hundred shiploads might be taken from it at one time."[10]

In 1846, Baku (settlement Bibi-Heybat) the first ever well was drilled with percussion tools to a depth of 21 metres (69 ft) for oil exploration. In 1846–1848, the first modern oil wells were drilled on the Absheron Peninsula north-east of Baku, by Russian engineer Vasily Semyonov applying the ideas of Nikolay Voskoboynikov.[11]

Ignacy Łukasiewicz, a Polish[12][13] pharmacist and petroleum industry pioneer drilled one of the world's first modern oil wells in 1854 in Polish village Bóbrka, Krosno County[14], and in 1856 built one of the world's first oil refineries.[15]

In North America, the first commercial oil well entered operation in Oil Springs, Ontario in 1858, while the first offshore oil well was drilled in 1896 in the Summerland Oil Field on the California Coast.[16]

The earliest oil wells in modern times were drilled percussively, by repeatedly raising and dropping a bit on the bottom of a cable into the borehole. In the 20th century, cable tools were largely replaced with rotary drilling, which could drill boreholes to much greater depths and in less time.[17] The record-depth Kola Borehole used a mud motor while drilling to achieve a depth of over 12,000 metres (12 km; 39,000 ft; 7.5 mi).[18]

Until the 1970s, most oil wells were essentially vertical, although lithological variations cause most wells to deviate at least slightly from true vertical (see deviation survey). However, modern directional drilling technologies allow for highly deviated wells that can, given sufficient depth and with the proper tools, actually become horizontal. This is of great value as the reservoir rocks that contain hydrocarbons are usually horizontal or nearly horizontal; a horizontal wellbore placed in a production zone has more surface area in the production zone than a vertical well, resulting in a higher production rate. The use of deviated and horizontal drilling has also made it possible to reach reservoirs several kilometers or miles away from the drilling location (extended reach drilling), allowing for the production of hydrocarbons located below locations that are difficult to place a drilling rig on, environmentally sensitive, or populated.

Life of a well

Planning

- For a production well, the target is picked to optimize production from the well and manage reservoir drainage.

- For an exploration or appraisal well, the target is chosen to confirm the existence of a viable hydrocarbon reservoir or to learn its extent.

- For an injection well, the target is selected to locate the point of injection in a permeable zone that may support disposing of water or gas and/or pushing hydrocarbons into nearby production wells.

The target (the endpoint of the well) will be matched with a surface location (the starting point of the well), and a trajectory between the two will be designed. There are many considerations to take into account when designing the trajectory such as the clearance from any nearby wells (anti-collision) or future wellpaths.

Before a well is drilled, a geologic target is identified by a geologist or geophysicist to meet the objectives of the well. When the well path is identified, a team of geoscientists and engineers will develop a set of presumed characteristics of the subsurface path that will be drilled through to reach the target. These properties may include lithology pore pressure, fracture gradient, wellbore stability, porosity and permeability. These assumptions are used by a well engineering team designing the casing and completion programs for the well. Also considered in the detailed planning are selection of the drill bits, bottom hole assembly, and the drilling fluid. Step-by-step procedures are written to provide guidelines for executing the well in a safe and cost-efficient manner.

With the interplay with many of the elements in a well's design, trajectories and designs often go through several iterations before the plan is finalized.

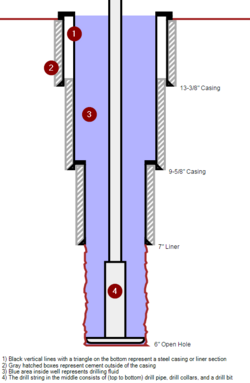

Drilling

The well is created by drilling a hole 12 cm to 1 meter (5 in to 40 in) in diameter into the earth with a drilling rig that rotates a drill string with a bit attached. At depths during the process, sections of steel pipe (casing), slightly smaller in diameter than the borehole at that point, are placed in the hole. Cement slurry will be pumped down the inside to rise in the annulus between the borehole and the outside of the casing. The casing provides structural integrity to that portion of the newly drilled wellbore, in addition to isolating potentially dangerous high pressure zones from lower-pressure ones, and from the surface.

With these zones safely isolated and the formation protected by the casing, the well can be drilled deeper (into potentially higher-pressure or more-unstable formations) with a smaller bit, and then cased with a smaller size pipe. Modern wells generally have two to as many as five sets of subsequently smaller hole sizes, each cemented with casing.

To drill the well

- The rotating drill bit, aided by the weight of the drill string above it, cuts into the rock. There are different types of drill bits; some cause the rock to disintegrate by compressive failure, while others shear slices off the rock as the bit turns.

- Drilling fluid, a.k.a. "mud", is pumped down the inside of the drill pipe and exits at the drill bit. The principal components of drilling fluid are usually water and clay, but it also typically contains a complex mixture of fluids, solids and chemicals that must be carefully tailored to provide the correct physical and chemical characteristics required to safely drill the well. Particular functions of the drilling mud include cooling the bit, lifting rock cuttings to the surface, preventing destabilisation (spalling) of the rock in the wellbore, and overcoming the pressure of fluids inside the rock so that these fluids do not enter the wellbore. Some oil wells are drilled with air or foam as the drilling fluid.

- The generated rock "cuttings" are swept up by the drilling fluid as it circulates back to the surface inside the casing and outside of the drill pipe. The fluid then goes through "shakers" that screen the cuttings out of the fluid, which is returned to the pit for reuse. Watching for abnormalities in the returning cuttings and monitoring pit volume or rate of returning fluid are imperative to catch "kicks" early. A "kick" is when the formation pressure at the depth of the bit is greater than the hydrostatic head of the mud above, which if not controlled temporarily by closing the blowout preventers followed by increasing the density of the drilling fluid would allow formation fluids to enter the annulus uncontrollably.

- The drill string to which the bit is attached is gradually lengthened as the well gets deeper by screwing in additional 9 m (30 ft) sections or "joints" of pipe under the kelly or top drive at the surface. This process is called "making a connection". The operation called "tripping" is when pulling the bit out of the hole to replace the bit (tripping out), and running back in with a new bit (tripping in). Joints are usually combined for more efficient tripping by creating stands of multiple joints. A conventional triple, for example, has three joints at a time racked vertically in the derrick. Some modern rigs, called "super singles", trip pipe one at a time, laying it out on racks as they go.

This process is all facilitated by a drilling rig, which contains all necessary equipment to circulate the drilling fluid, hoist and rotate the pipe, remove cuttings from the drilling fluid, and generate on-site power for these operations.

Completion

After drilling and casing the well, it must be 'completed'. Completion is the process in which the well is prepared to produce oil or gas.

In a cased-hole completion, small perforations are made in the portion of the casing across the production zone, to provide a path for the oil to flow from the surrounding rock into the production tubing. In open hole completion, often a 'sand screen' or 'gravel pack' is installed in the last-drilled but uncased reservoir section. These maintain structural integrity of the wellbore in the absence of casing, while still allowing flow from the reservoir into the borehole. Screens also control the migration of formation sands into production tubulars, which can lead to washouts and other problems, particularly from unconsolidated sand formations.

After a flow path is made, acids and fracturing fluids may be pumped into the well to fracture, clean, or otherwise prepare and stimulate the reservoir rock to allow optimal production of hydrocarbons into the wellbore. Usually the area above the producing section of the well is packed off inside the casing, and connected to the surface via a smaller diameter pipe called tubing. This arrangement provides a redundant barrier to leaks of hydrocarbons as well as allowing damaged sections to be replaced. Also, the smaller cross-sectional area of the tubing gives reservoir fluids an increased velocity to minimize liquid fallback that would create additional back pressure, and shields the casing from corrosive well fluids.

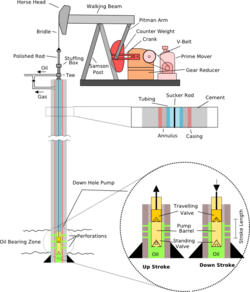

In many wells, the natural pressure of the subsurface reservoir is high enough for the oil or gas to flow to the surface. However, this is not always the case, especially in depleted fields where the pressures have been lowered by other producing wells, or in low-permeability oil reservoirs. Installing a smaller diameter tubing may be enough to help the production, but artificial lift methods may also be needed. Common solutions include surface pump jacks, downhole hydraulic pumps or gas lift assistance. Many new systems in recent years have been introduced for well completion. Multiple packer systems with frac ports or port collars in an all-in-one system have cut completion costs and improved production, especially in the case of horizontal wells. These new systems allow casing to run into the lateral zone equipped with proper packer/frac-port placement for optimal hydrocarbon recovery.

Production

The production stage is the most important stage of a well's life: when the oil and gas are produced. By this time, the oil rigs and workover rigs used to drill and complete the well will have moved off the wellbore, and the top is usually outfitted with a collection of valves called a Christmas tree or production tree. These valves regulate pressures, control flows, and allow access to the wellbore in case further completion work is needed. From the outlet valve of the production tree, the flow can be connected to a distribution network of pipelines and tanks to supply the product to refineries, natural gas compressor stations, or oil export terminals.

As long as the pressure in the reservoir remains high enough, the production tree is all that is required to produce the well. If the pressure depletes and it is considered economically viable, an artificial lift method mentioned in the completions section can be employed.

Workovers are often necessary in older wells, which may need smaller diameter tubing, scale or paraffin removal, acid matrix jobs, or completion in new zones of interest in a shallower reservoir. Such remedial work can be performed using workover rigs – also known as pulling units, completion rigs or "service rigs" – to pull and replace tubing, or by the use of well intervention techniques utilizing coiled tubing. Depending on the type of lift system and wellhead a rod rig or flushby can be used to change a pump without pulling the tubing.

Enhanced recovery methods such as water flooding, steam flooding, or CO2 flooding may be used to increase reservoir pressure and provide a "sweep" effect to push hydrocarbons out of the reservoir. Such methods require the use of injection wells (often chosen from old production wells in a carefully determined pattern), and are used when facing problems with reservoir pressure depletion or high oil viscosity, sometimes being employed early in a field's life. In certain cases – depending on the reservoir's geomechanics – reservoir engineers may determine that ultimate recoverable oil may be increased by applying a waterflooding strategy early in the field's development rather than later. Such enhanced recovery techniques are often called Secondary or "tertiary recovery".

Abandonment

Types of wells

By produced fluid

- Wells that produce crude oil

- Wells that produce crude oil and natural gas, or

- Wells that only produce natural gas.

Natural gas, in a raw form known as associated petroleum gas, is almost always a by-product of producing oil.[19] The short, light-gas carbon chains come out of solution when undergoing pressure reduction from the reservoir to the surface, similar to uncapping a bottle of soda where the carbon dioxide effervesces. If it escapes into the atmosphere intentionally it is known as vented gas, or if unintentionally as fugitive gas.

Unwanted natural gas can be a disposal problem at wells that are developed to produce oil. If there are no pipelines for natural gas near the wellhead it may be of no value to the oil well owner since it cannot reach the consumer markets. Such unwanted gas may then be burned off at the well site in a practice known as production flaring, but due to the energy resource waste and environmental damage concerns this practice is becoming less common.[20]

Often, unwanted (or 'stranded' gas without a market) gas is returned back into the reservoir with an 'injection' well for storage or for re-pressurizing the producing formation. Another solution is to convert the natural gas to a liquid fuel. Gas to liquid (GTL) is a developing technology that converts stranded natural gas into synthetic gasoline, diesel or jet fuel through the Fischer–Tropsch process developed in World War II Germany. Like oil, such dense liquid fuels can be transported using conventional tankers for trucking to refineries or users. Proponents claim GTL fuels burn cleaner than comparable petroleum fuels. Most major international oil companies are in advanced development stages of GTL production, e.g. the 140,000 bbl/d (22,000 m3/d) Pearl GTL plant in Qatar. In locations such as the United States with a high natural gas demand, pipelines are usually favored to take the gas from the well site to the end consumer.

By location

Wells can be located:

- Onshore, or

- Offshore

Offshore wells can further be subdivided into

- Wells with subsea wellheads, where the top of the well is sitting on the ocean floor under water, and often connected to a pipeline on the ocean floor.

- Wells with 'dry' wellheads, where the top of the well is above the water on a platform or jacket, which also often contains processing equipment for the produced fluid.

While the location of the well will be a large factor in the type of equipment used to drill it, there is actually little downhole difference in the well itself. An offshore well targets a reservoir that happens to be underneath an ocean. Due to logistics and specialized equipment needed, drilling an offshore well is far more costly than a comparable onshore well.[21] These wells dot the Southern and Central Great Plains, Southwestern United States, and are the most common wells in the Middle East.

By purpose

Another way to classify oil wells is by their purpose in contributing to the development of a resource. They can be characterized as:

- wildcat wells that are drilled where little or no known geological information is available. The site may have been selected because of wells drilled some distance from the proposed location but to an underground structure that appeared similar to the proposed site. Individuals who drill wildcat wells are known as 'wildcatters'.

- exploration wells are drilled purely for exploratory (information gathering) purposes in a new area. The site selection is usually based on seismic data, satellite surveys, etc. Details gathered in this well include the presence of hydrocarbon in the drilled location, the amount of fluid present and the depth at which oil or gas occurs.

- appraisal wells may be needed to assess characteristics (such as flow rate, reservoir quantity) of a proven hydrocarbon accumulation. Such wells reduce uncertainty about the characteristics and properties of the hydrocarbon present in the field.

- production wells are drilled primarily for producing oil or gas, once the producing structure and characteristics are determined.

- development wells are wells drilled for the production of oil or gas already proven by appraisal drilling to be suitable for exploitation.

- abandoned wells are wells permanently plugged in the drilling phase for technical reasons, or that had failed to locate commercially valuable hydrocarbons.

At a producing well site, active wells may be further categorized as:

- oil producers producing predominantly liquid hydrocarbons, but most include some associated gas.

- gas producers producing almost entirely gaseous hydrocarbons, consisting mostly of natural gas.

- water injectors injecting water into the formation to maintain reservoir pressure, or simply to dispose of water produced with the hydrocarbons because even after treatment, it would be too oily and too saline to be considered clean for dumping overboard offshore, let alone into a fresh water resource in the case of onshore wells. Water injection into the producing zone frequently has a beneficial element of reservoir management; however, often produced water disposal is into shallower zones safely beneath any fresh water zones.

- aquifer producers intentionally producing water for re-injection to manage pressure. If possible this water will come from the reservoir itself. Using aquifer produced water rather than water from other sources is to preclude chemical incompatibility that might lead to reservoir-plugging precipitates. These wells will generally be needed only if produced water from the oil or gas producers is insufficient for reservoir management purposes.

- gas injectors injecting gas into the reservoir often as a means of disposal or sequestering for later production, but also to maintain reservoir pressure.

Lahee classification[22]

- New Field Wildcat (NFW) – far from other producing fields and on a structure that has not previously produced.

- New Pool Wildcat (NPW) – new pools on already producing structure.

- Deeper Pool Test (DPT) – on already producing structure and pool, but on a deeper pay zone.

- Shallower Pool Test (SPT) – on already producing structure and pool, but on a shallower pay zone.

- Outpost (OUT) – usually two or more locations from nearest productive area.

- Development Well (DEV) – can be on the extension of a pay zone, or between existing wells (Infill).

Cost

The cost to drill a well depends mainly on the daily rate of the drilling rig, the extra services required to drill the well, the duration of the well program (including downtime and weather time), and the remoteness of the location (logistic supply costs).[23]

The daily rates of offshore drilling rigs vary by their depth capability and availability. Rig rates reported by an industry web service[24] show that deepwater drilling rigs are over twice the daily cost of the shallow water fleet, and rates for jack-up fleet can vary by factor of 3 depending upon capability.

With deepwater drilling rig rates in 2015 of around $520,000/day,[24] and similar additional spread costs, a deepwater well of a duration of 100 days can cost around US$100 million.[25]

With high-performance jack-up rig rates in 2015 of around $177,000/day[24] with similar service costs, a high pressure, high-temperature well of duration 100 days can cost about US$30 million.

Onshore wells can be considerably cheaper, particularly if the field is at a shallow depth, where costs range from less than $4.9 million to $8.3 million, and the average completion costing $2.9 million to $5.6 million per well.[26] Completion makes up a larger portion of onshore well costs than offshore wells, which generally have the added cost burden of a surface platform.[27]

The total costs mentioned do not include those associated with the risk of explosion and leakage of oil. Those costs include the cost of protecting against such disasters, the cost of the cleanup effort, and the hard-to-calculate cost of damage to the company's image.[28]

Impacts on wildlife

The impacts of oil exploration and drilling are often irreversible, particularly for wildlife.[29] Research indicates that caribou in Alaska show a marked avoidance of areas near oil wells and seismic lines due to disturbances.[29] Drilling often destroys wildlife habitat, causing wildlife stress, and breaks up large areas into smaller isolated ones, changing the environment, and forcing animals to migrate elsewhere.[30][29] It can also bring in new species that compete with or prey on existing animals.[30] Even though the actual area taken up by oil and gas equipment might be small, negative effects can spread. Animals like mule deer and elk try to stay away from the noise and activity of drilling sites, sometimes moving miles away to find peace. This movement and avoidance can lead to less space for these animals affecting their numbers and health.[31]

The Sage-grouse is another example of an animal that tries to avoid areas with drilling, which can lead to fewer of them surviving and reproducing.[30] Different studies show that drilling in their habitats negatively impacts sage-grouse populations. In Wyoming, sage grouse studied between 1984 and 2008 show a roughly 2.5 percent annual population decline in males, correlating with the density of oil and gas wells.[32] Factors such as sagebrush cover and precipitation seemed to have little effect on count changes. These results align with other studies highlighting the detrimental impact of oil and gas development on sage-grouse populations.

See also

- Engineering:Offshore drilling – Mechanical process where a wellbore is drilled below the seabed

- Engineering:Oil well control – Management of oil wells

- Earth:Oil spill – Release of petroleum into the environment

- Engineering:Thermomechanical cuttings cleaner

References

- ↑ "Special Report: Millions of abandoned oil wells are leaking methane, a climate menace" (in en). Reuters. 2020-06-17. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-drilling-abandoned-specialreport-idUSKBN23N1NL.

- ↑ "More Exposures from Abandoned Oil and Gas Wells Come Into Focus" (in en-us). 13 July 2020. https://www.verisk.com/insurance/covid-19/iso-insights/more-exposures-from-abandoned-oil-and-gas-wells-come-into-focus/.

- ↑ "A timeline from the histories of ASTM Committee D02 and the petroleum industry". https://www.astm.org/COMMIT/D02/to1899_index.html.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEB1911 - ↑ Robert James Forbes (1958). Studies in Early Petroleum History. Brill Archive. p. 180. https://books.google.com/books?id=eckUAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA180.

- ↑ Dr. Kasem Ajram (1992). The Miracle of Islam Science (2nd ed.). Knowledge House Publishers. ISBN 0-911119-43-4.

- ↑ Russell, James M. (1 November 2018) (in en). Plato's Alarm Clock: And Other Amazing Ancient Inventions. Michael O'Mara Books. ISBN 978-1-78243-935-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=IqxxDwAAQBAJ&dq=petroleum+%22Muhammad+ibn+Zakar%C4%ABya+R%C4%81zi%22+kerosene&pg=PT73.

- ↑ Zayn Bilkadi (University of California, Berkeley), "The Oil Weapons", Saudi Aramco World, January–February 1995, pp. 20–27

- ↑ Joseph P. Riva Jr. and Gordon I. Atwater. "petroleum". Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/454269/petroleum. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ↑ Steil, Tim. Fantastic Filling Stations. Voyageur Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-1610606295.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Oil and Gas Drilling" (in en). http://visions.az/en/news/366/4ca556e3/.

- ↑ Magdalena Puda-Blokesz, Ignacy Łukasiewicz: ojciec światowego przemysłu naftowego, działacz polityczny i patriota, filantrop i społecznik, przede wszystkim Człowiek

- ↑ Ludwik Tomanek, Ignacy Łukasiewicz twórca przemysłu naftowego w Polsce, wielki inicjator – wielki jałmużnik. Miejsce Piastowe: Komitet Uczczenia Pamięci Ignacego Łukasiewicza. 1928

- ↑ "Skansen Przemysłu Naftowego w Bóbrce / Museum of Oil Industry at Bobrka". Archived from the original on May 19, 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070519031720/http://www.geo.uw.edu.pl/BOBRKA/DATY/daty.htm.

- ↑ Frank, Alison Fleig (2005). Oil Empire: Visions of Prosperity in Austrian Galicia (Harvard Historical Studies). Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01887-7.

- ↑ "Canada Cool I North America's first commercial oil – Oil Springs" (in en-US). http://www.canadacool.com/location/oil-springs-first-commercial-oil-well/.

- ↑ "Location – Leverage Oilfield and Industrial Supply" (in en-US). http://www.loisco.com/about/.

- ↑ "How did the ingenious use of bamboo poles help drill the first oil wells?" (in en-US). 2020-05-31. https://oilnow.gy/featured/how-did-the-ingenious-use-of-bamboo-poles-help-drill-the-first-oil-wells/.

- ↑ Croft, Cameron P.. "How Do You Process Natural Gas?" (in en-US). https://www.croftsystems.net/oil-gas-blog/how-do-you-process-natural-gas/.

- ↑ Emam, Eman A. (December 2015). "Gas Flaring in Industry: an Overview". http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2016/ph240/miller1/docs/emam.pdf.

- ↑ "Crude Oil and Natural Gas Drilling Activity". U.S. Energy Information Administration. 21 May 2019. https://www.eia.gov/dnav/ng/ng_enr_drill_s1_a.htm.

- ↑ Drilling Well Classification System

- ↑ International, Petrogav (in en). Drilling Course for Hiring on Onshore Drilling Rigs. Petrogav International. https://books.google.com/books?id=US7JDwAAQBAJ&q=The+cost+of+a+well+depends+mainly+on+the+daily+rate+of+the+drilling+rig%2C+the+extra+services+required+to+drill+the+well%2C+the+duration+of+the+well+program&pg=PA218.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Rigzone – Rig day rates : http://www.rigzone.com/data/dayrates/

- ↑ Center, Petrogav International Oil & Gas Training (2020-07-02) (in en). The technological process on Offshore Drilling Rigs for fresher candidates. Petrogav International. https://books.google.com/books?id=stjuDwAAQBAJ&q=a+deep+water+well+of+duration+of+100+days+can+cost+around+US%24100+million&pg=PA198.

- ↑ "Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs". U.S. Energy Information Administration. 2016. https://www.eia.gov/analysis/studies/drilling/pdf/upstream.pdf.

- ↑ "The Cost of Oil & Gas Wells". Oil Scams. 2018. http://www.oilscams.org/how-much-does-oil-gas-well-cost.

- ↑ "How Much Does an Oil & Gas Well Cost?| Oil & Gas Investing Advice". http://www.oilscams.org/how-much-does-oil-gas-well-cost.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Lauren Bettino, Hank Moylan, Victoria Stukas (3 December 2015). "Impacts of Oil Drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge". https://websites.umass.edu/natsci397a-eross/impacts-of-oil-drilling-in-the-arctic-national-wildlife-refuge/. "This article provides an in-depth analysis of the potential impacts of oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge"

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 "Development of Oil and Gas". https://wgfd.wyo.gov/Habitat/Habitat-Information/Development-of-Oil-and-Gas. "This resource provides comprehensive information on the impacts of oil and gas development on wildlife habitats within Wyoming."

- ↑ "Study Quantifies Drilling Impacts on Mule Deer". 18 August 2015. https://www.hcn.org/articles/study-quantifies-drilling-impacts-on-mule-deer/. "This article discusses a study that quantifies the impacts of oil and gas drilling on mule deer populations."

- ↑ Green, Adam W.; Aldridge, Cameron L.; O'Donnell, Michael S. (2016). "Impacts of Oil and Gas Development on Sage-Grouse Populations in Wyoming". The Journal of Wildlife Management (Wildlife Society Bulletin) 81 (1): 46–57. doi:10.1002/jwmg.21179. https://wildlife.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jwmg.21179. Retrieved 2024-03-21. "This study examines the decline of sage-grouse populations in Wyoming".

External links

- Halliburton Technical Papers

- Freemyer Industrial Pressure

- Schlumberger Oilfield Glossary

- The History of the Oil Industry

- "Black Gold" Popular Mechanics, January 1930 – photo article on oil drilling in the 1920s and 1930s

- "World's Deepest Well" Popular Science, August 1938, article on the late 1930s technology of drilling oil wells

- Brief history of oil and gas production

- Mir-Babayev M.F. "Brief history of the first drilled oil well; and the people involved". Oil-Industry History (US), 2017, v. 18 #1, pp. 25–34

|

KSF

KSF