Outer Space Treaty

Topic: Engineering

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

Long name:

| |

|---|---|

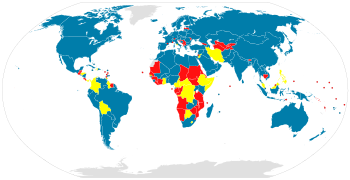

Parties Signatories Non-parties | |

| Signed | 27 January 1967 |

| Location | London, Moscow and Washington, D.C. |

| Effective | 10 October 1967 |

| Condition | 5 ratifications, including the depositary Governments |

| Parties | 114[1][2][3][4] |

| Depositary | Governments of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the United States of America |

| Languages | English, French, Russian, Spanish, Chinese and Arabic |

The Outer Space Treaty, formally the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies, is a multilateral treaty that forms the basis of international space law. Negotiated and drafted under the auspices of the United Nations, it was opened for signature in the United States , the United Kingdom , and the Soviet Union on 27 January 1967, entering into force on 10 October 1967. (As of August 2023), 114 countries are parties to the treaty—including all major spacefaring nations—and another 22 are signatories.[1][5][6]

The Outer Space Treaty was spurred by the development of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in the 1950s, which could reach targets through outer space.[7] The Soviet Union's launch of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite, in October 1957, followed by a subsequent arms race with the United States, hastened proposals to prohibit the use of outer space for military purposes. On 17 October 1963, the U.N. General Assembly unanimously adopted a resolution prohibiting the introduction of weapons of mass destruction in outer space. Various proposals for an arms control treaty governing outer space were debated during a General Assembly session in December 1966, culminating in the drafting and adoption of the Outer Space Treaty the following January.[8]

Key provisions of the Outer Space Treaty include prohibiting nuclear weapons in space; limiting the use of the Moon and all other celestial bodies to peaceful purposes; establishing that space shall be freely explored and used by all nations; and precluding any country from claiming sovereignty over outer space or any celestial body. Although it forbids establishing military bases, testing weapons and conducting military maneuvers on celestial bodies, the treaty does not expressly ban all military activities in space, nor the establishment of military space forces or the placement of conventional weapons in space.[9][10] From 1968 to 1984, the OST birthed four additional agreements: rules for activities on the Moon; liability for damages caused by spacecraft; the safe return of fallen astronauts; and the registration of space vehicles.[11]

OST provided many practical uses and was the most important link in the chain of international legal arrangements for space from the late 1950s to the mid-1980s. OST was at the heart of a 'network' of inter-state treaties and strategic power negotiations to achieve the best available conditions for nuclear weapons world security. The OST also declares that space is an area for free use and exploration by all and "shall be the province of all mankind". Drawing heavily from the Antarctic Treaty of 1961, the Outer Space Treaty likewise focuses on regulating certain activities and preventing unrestricted competition that could lead to conflict.[12] Consequently, it is largely silent or ambiguous on newly developed space activities such as lunar and asteroid mining.[13][14][15] Nevertheless, the Outer Space Treaty is the first and most foundational legal instrument of space law,[16] and its broader principles of promoting the civil and peaceful use of space continue to underpin multilateral initiatives in space, such as the International Space Station and the Artemis Program.[17][18]

Provisions

The Outer Space Treaty represents the basic legal framework of international space law. According to the U.N. Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), the core principles of the treaty are:[19]

- the exploration and use of outer space shall be carried out for the benefit and in the interests of all countries and shall be the province of all mankind;

- outer space shall be free for exploration and use by all States;

- outer space is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means;

- States shall not place nuclear weapons or other weapons of mass destruction in orbit or on celestial bodies or station them in outer space in any other manner;

- the Moon and other celestial bodies shall be used exclusively for peaceful purposes; prohibits their use for testing weapons of any kind, conducting military maneuvers, or establishing military bases, installations, and fortifications

- astronauts shall be regarded as the envoys of mankind;

- States shall be responsible for national space activities whether carried out by governmental or non-governmental entities;

- States shall be liable for damage caused by their space objects; and

- States shall avoid harmful contamination of space and celestial bodies.

Among its principles, it bars states party to the treaty from placing weapons of mass destruction in Earth orbit, installing them on the Moon or any other celestial body, or otherwise stationing them in outer space. It specifically limits the use of the Moon and other celestial bodies to peaceful purposes, and expressly prohibits their use for testing weapons of any kind, conducting military maneuvers, or establishing military bases, installations, and fortifications (Article IV). However, the treaty does not prohibit the placement of conventional weapons in orbit, and thus some highly destructive attack tactics, such as kinetic bombardment, are still potentially allowable.[20] In addition, the treaty explicitly allows the use of military personnel and resources to support peaceful uses of space, mirroring a common practice permitted by the Antarctic Treaty regarding that continent. The treaty also states that the exploration of outer space shall be done to benefit all countries and that space shall be free for exploration and use by all the states.

Article II of the treaty explicitly forbids any government from claiming a celestial body such as the Moon or a planet as its own territory, whether by declaration, occupation, or "any other means".[21] However, the state that launches a space object, such as a satellite or space station, retains jurisdiction and control over that object;[22] by extension, a state is also liable for damages caused by its space object.[23]

Responsibility for activities in space

Article VI of the Outer Space Treaty deals with international responsibility, stating that "the activities of non-governmental entities in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, shall require authorization and continuing supervision by the appropriate State Party to the Treaty" and that States Party shall bear international responsibility for national space activities whether carried out by governmental or non-governmental entities.

As a result of discussions arising from Project West Ford in 1963, a consultation clause was included in Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty: "A State Party to the Treaty which has reason to believe that an activity or experiment planned by another State Party in outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, would cause potentially harmful interference with activities in the peaceful exploration and use of outer space, including the Moon and other celestial bodies, may request consultation concerning the activity or experiment."[24][25]

Applicability in the 21st century

Being primarily an arms control treaty for the peaceful use of outer space, the Outer Space Treaty offers limited and ambiguous regulations to newer space activities such as lunar and asteroid mining.[13][15][26] It is therefore debated whether the extraction of resources falls within the prohibitive language of appropriation, or whether the use of such resources encompasses the commercial use and exploitation.[27]

Seeking clearer guidelines, private U.S. companies lobbied the U.S. government, which in 2015 introduced the U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act of 2015 legalizing space mining.[28] Similar national legislation to legalize the appropriation of extraterrestrial resources are now being introduced by other countries, including Luxembourg, Japan, China, India, and Russia.[13][26][29][30] This has created some controversy regarding legal claims over the mining of celestial bodies for profit.[26][27]

1976 Bogota Declaration

The "Declaration of the First Meeting of Equatorial Countries", also known as the "Bogota Declaration", was one of the few attempts to challenge the Outer Space Treaty. It was promulgated in 1976 by eight equatorial countries to assert sovereignty over those portions of the geostationary orbit that continuously lie over the signatory nations' territory.[31] These claims did not receive wider international support or recognition, and were subsequently abandoned.[32]

Influence on space law

As the first international legal instrument concerning space, the Outer Space Treaty is considered the "cornerstone" of space law.[33][34] It was also the first major achievement of the United Nations in this area of law, following the adoption of the first U.N. General Assembly resolution on space in 1958,[35] and the first meeting of the U.N. Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) the subsequent year.[36]

Within roughly a decade of the treaty's entry into force, several other treaties were brokered by the U.N. to further develop the legal framework for activities in space:[37]

- Rescue Agreement (1968)

- Space Liability Convention (1972)

- Registration Convention (1976)

- Moon Treaty (1979)

With the exception of the Moon Treaty, to which only 18 nations are party, all other treaties on space law have been ratified by most major space-faring nations (namely those capable of orbital spaceflight).[38] COPUOS coordinates these treaties and other questions of space jurisdiction, aided by the U.N. Office for Outer Space Affairs.

List of parties

The Outer Space Treaty was opened for signature in the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union on 27 January 1967, and entered into force on 10 October 1967. As of August 2023, 114 countries are parties to the treaty, while another 22 have signed the treaty but have not completed ratification.[1]

Multiple dates indicate the different days in which states submitted their signature or deposition, which varied by location: (L) for London, (M) for Moscow, and (W) for Washington, D.C. Also indicated is whether the state became a party by way of signature and subsequent ratification, by accession to the treaty after it had closed for signature, or by succession of states after separation from some other party to the treaty.

| State[1][2][3][4] | Signed | Deposited | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Ratification | |

| 1992 (W) | Accession | ||

|

Succession from | ||

|

1969 (M, W) | Ratification | |

| 2018 (M) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (W) | 1967 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1968 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 2015 (L) | Accession | ||

|

Succession from | ||

| 2019 (M) | Accession | ||

|

Accession | ||

| 1968 (W) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (M) | 1967 (M) | Ratification | |

|

|

Ratification | |

|

Accession | ||

| 2020 (L) | Accession | ||

|

1969 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) |

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (W) | 1968 (W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1967 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

|

1981 (W) | Ratification | |

|

Accession | ||

| 2023 (W) | Accession | ||

| 1977 (M) | Accession | ||

|

|

Ratification | |

|

Succession from | ||

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1967 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (W) | 1968 (W) | Ratification | |

|

1969 (W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (M, W) |

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (W) | 1969 (W) | Ratification | |

| 1989 (M) | Accession | ||

| 2010 (M) | Accession | ||

|

Succession from | ||

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1967 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1970 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1971 (L, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (W) | 1971 (L) | Ratification | |

| 1976 (M) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1967 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1968 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1982 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

|

2002 (L) | Ratification | |

|

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, W) |

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) |

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1972 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) |

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1967 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1998 (M) | Accession | ||

| 1984 (L) | Accession | ||

| 2009 (M) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (W) | 1967 (W) | Ratification | |

|

Accession | ||

|

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) |

|

Ratification | |

| 1968 (W) | Accession | ||

| 2013 (W) | Accession | ||

|

2006 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1968 (W) | Accession | ||

| 1968 (M) | Accession | ||

| 2017 (L) | Accession | ||

|

Succession from | ||

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1968 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (M) | 1967 (M) | Ratification | |

|

Accession | ||

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1970 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

|

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1969 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1968 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

|

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (W) |

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (L) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1969 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 2022 (L) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1968 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (W) | 2023 (W) | Ratification | |

|

Succession from | ||

| 2016 (L) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (W) |

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1968 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1996 (L) | Accession | ||

| 2012 (W) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1968 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1967 (L, M, W) | Ratification as the | |

| 1999 (L) | Succession from | ||

|

|

Ratification | |

| 1976 (W) | Accession | ||

| 1978 (L) | Accession | ||

|

|

Ratification | |

| 1976 (L, M, W) | Accession | ||

|

Succession from | ||

| 2019 (L) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (W) |

|

Ratification | |

|

Accession | ||

| 1967 (L) | 1986 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1967 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

|

1969 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1968 (M) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (L, M, W) |

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (W) | 1989 (W) | Ratification | |

|

Succession from | ||

|

|

Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1968 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1968 (W) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (M) | 1967 (M) | Ratification | |

| 2000 (W) | Accession | ||

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1967 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (L, M, W) | 1967 (L, M, W) | Ratification | |

|

1970 (W) | Ratification | |

| 1967 (W) | 1970 (W) | Ratification | |

| 1980 (M) | Accession | ||

| 1979 (M) | Accession | ||

|

Accession |

Partially recognized state abiding by treaty

The Republic of China (Taiwan), which is currently recognized by [[International recognition of Template:Numrec/ROC Template:Numrec/ROC|Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "[". UN member states]], ratified the treaty prior to the United Nations General Assembly's vote to transfer China's seat to the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1971. When the PRC subsequently ratified the treaty, they described the Republic of China's (ROC) ratification as "illegal". The ROC has committed itself to continue to adhere to the requirements of the treaty, and the United States has declared that it still considers the ROC to be "bound by its obligations".[5]

| State | Signed | Deposited | Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | 1970 | Ratification |

States that have signed but not ratified

22 states have signed but not ratified the treaty.

| State | Signed |

|---|---|

| 1967 (W) | |

| 1967 (W) | |

| 1967 (W) | |

| 1967 (W) | |

| 1967 (W) | |

| 1967 (W) | |

| |

| |

| 1967 (L) | |

| |

| 1967 (W) | |

| 1967 (W) | |

| 1967 (L) | |

| 1967 (W) | |

| 1967 (L) | |

| 1967 (W) | |

| 1967 (W) | |

| |

| |

| 1967 (W) | |

| 1967 (W) | |

|

List of non-parties

The remaining UN member states and United Nations General Assembly observer states which have neither ratified nor signed the Outer Space Treaty are:

Albania

Albania Andorra

Andorra Angola

Angola Belize

Belize Bhutan

Bhutan Brunei

Brunei Cambodia

Cambodia Cape Verde

Cape Verde Chad

Chad Comoros

Comoros Republic of the Congo

Republic of the Congo Costa Rica

Costa Rica Djibouti

Djibouti Dominica

Dominica East Timor

East Timor Eritrea

Eritrea Eswatini

Eswatini Gabon

Gabon Georgia

Georgia Grenada

Grenada Guatemala

Guatemala Guinea

Guinea Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast Kiribati

Kiribati Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Liechtenstein

Liechtenstein Malawi

Malawi Maldives

Maldives Marshall Islands

Marshall Islands Mauritania

Mauritania Federated States of Micronesia

Federated States of Micronesia Moldova

Moldova Monaco

Monaco Montenegro

Montenegro Mozambique

Mozambique Namibia

Namibia Nauru

Nauru North Macedonia

North Macedonia Palau

Palau Palestine

Palestine Saint Kitts and Nevis

Saint Kitts and Nevis Saint Lucia

Saint Lucia Samoa

Samoa São Tomé and Príncipe

São Tomé and Príncipe Senegal

Senegal Serbia

Serbia Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands South Sudan

South Sudan Sudan

Sudan Suriname

Suriname Tajikistan

Tajikistan Tanzania

Tanzania Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan Tuvalu

Tuvalu Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan Vanuatu

Vanuatu Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

See also

- High-altitude nuclear explosion (HANE)

- Kármán line

- Lunar Flag Assembly

- Common heritage of mankind

- Human presence in space

- Militarization of space

- Moon Treaty

- SPACE Act of 2015

- Treaty on Open Skies

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

- International waters

- International zone

- Extraterritorial jurisdiction

- Extraterritorial operation

- Extraterritoriality

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. https://treaties.unoda.org/t/outer_space.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "TREATY ON PRINCIPLES GOVERNING THE ACTIVITIES OF STATES IN THE EXPLORATION AND USE OF OUTER SPACE, INCLUDING THE MOON AND OTHER CELESTIAL BODIES". Foreign and Commonwealth Office. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/447550/12._Exploration___Use_of_Outer_Space__1967__status_list.pdf.

"Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and other Celestial Bodies [London version"]. Foreign and Commonwealth Office. https://treaties.fco.gov.uk/awweb/pdfopener?md=1&did=70785. - ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, Including the Moon and other Celestial Bodies". United States Department of State. 30 June 2017. https://www.state.gov/outer-space-treaty.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Dohovor o pryncypach dejateľnosty hosudarstv po yssledovanyju y yspoľzovanyju kosmyčeskoho prostranstva, vkľučaja Lunu y druhye nebesnыe tela" (in ru). Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Russia. 16 January 2013. http://www.mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/international_contracts/multilateral_contract/-/storage-viewer/spm_md.nsf/webdt/page-4/290B54346D114D77C3257D8D003037EC?_storageviewer_WAR_storageviewerportlet_advancedSearch=false&_storageviewer_WAR_storageviewerportlet_keywords=1967&_storageviewer_WAR_storageviewerportlet_fromPage=search&_storageviewer_WAR_storageviewerportlet_andOperator=1.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "China: Accession to Outer Space Treaty". United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs. http://disarmament.un.org/treaties/a/outer_space/china/acc/washington.

- ↑ In addition, the Republic of China in Taiwan, which is currently recognized by [[International recognition of Template:Numrec/ROC Template:Numrec/ROC|Expression error: Unrecognized punctuation character "[". UN member states]], ratified the treaty prior to the United Nations General Assembly's vote to transfer China's seat to the People's Republic of China (PRC) in 1971.

- ↑ "Outer Space Treaty". https://2009-2017.state.gov/t/isn/5181.htm.

- ↑ "Outer Space Treaty". https://2009-2017.state.gov/t/isn/5181.htm.

- ↑ Shakouri Hassanabadi, Babak (30 July 2018). "Space Force and international space law". http://www.thespacereview.com/article/3543/1.

- ↑ Irish, Adam (13 September 2018). "The Legality of a U.S. Space Force". OpinioJuris. http://opiniojuris.org/2018/09/13/the-legality-of-a-u-s-space-force/.

- ↑ Buono, Stephen (2020-04-02). "Merely a 'Scrap of Paper'? The Outer Space Treaty in Historical Perspective". Diplomacy and Statecraft 31 (2): 350-372. doi:10.1080/09592296.2020.1760038.

- ↑ "Outer Space Treaty". https://2009-2017.state.gov/t/isn/5181.htm.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 If space is ‘the province of mankind’, who owns its resources? Senjuti Mallick and Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan. The Observer Research Foundation. 24 January 2019. Quote 1: "The Outer Space Treaty (OST) of 1967, considered the global foundation of the outer space legal regime, […] has been insufficient and ambiguous in providing clear regulations to newer space activities such as asteroid mining." *Quote2: "Although the OST does not explicitly mention "mining" activities, under Article II, outer space including the Moon and other celestial bodies are "not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty" through use, occupation or any other means."

- ↑ Szoka, Berin; Dunstan, James (1 May 2012). "Law: Is Asteroid Mining Illegal?". Wired. http://www.wired.com/2012/05/opinion-asteroid-mining/.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Who Owns Space? US Asteroid-Mining Act Is Dangerous And Potentially Illegal. IFL. Accessed on 9 November 2019. Quote 1: "The act represents a full-frontal attack on settled principles of space law which are based on two basic principles: the right of states to scientific exploration of outer space and its celestial bodies and the prevention of unilateral and unbriddled commercial exploitation of outer-space resources. These principles are found in agreements including the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 and the Moon Agreement of 1979." *Quote 2: "Understanding the legality of asteroid mining starts with the 1967 Outer Space Treaty. Some might argue the treaty bans all space property rights, citing Article II."

- ↑ "Space Law". https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/index.html.

- ↑ "International Space Station legal framework" (in en). https://www.esa.int/Science_Exploration/Human_and_Robotic_Exploration/International_Space_Station/International_Space_Station_legal_framework.

- ↑ "NASA: Artemis Accords". https://www.nasa.gov/specials/artemis-accords/index.html.

- ↑ "The Outer Space Treaty". https://www.unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html.

- ↑ Bourbonniere, M.; Lee, R. J. (2007). "Legality of the Deployment of Conventional Weapons in Earth Orbit: Balancing Space Law and the Law of Armed Conflict". European Journal of International Law 18 (5): 873. doi:10.1093/ejil/chm051.

- ↑ Frakes, Jennifer (2003). "The Common Heritage of Mankind Principle and the Deep Seabed, Outer Space, and Antarctica: Will Developed and Developing Nations Reach a Compromise?". Wisconsin International Law Journal: 409.

- ↑ Outer Space Treaty of 1967#Article VIII

- ↑ Wikisource:Outer Space Treaty of 1967#Article VII

- ↑ Terrill Jr., Delbert R. (May 1999), Project West Ford, "The Air Force Role in Developing International Outer Space Law" (PDF), Air Force History and Museums:63–67

- ↑ Wikisource:Outer Space Treaty of 1967#Article IX

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Davies, Rob (6 February 2016). "Asteroid mining could be space's new frontier: the problem is doing it legally.". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/feb/06/asteroid-mining-space-minerals-legal-issues.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Koch, Jonathan Sydney (2008). "Institutional Framework for the Province of all Mankind: Lessons from the International Seabed Authority for the Governance of Commercial Space Mining.". Astropolitics 16 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1080/14777622.2017.1381824.

- ↑ "U.S. Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act". Act No. H.R.2262 of 5 December 2015. 114th Congress (2015–2016) Sponsor: Rep. McCarthy, Kevin. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2262.

- ↑ Ridderhof, R. (18 December 2015). "Space Mining and (U.S.) Space Law". https://www.peacepalacelibrary.nl/2015/12/space-mining-and-u-s-space-law/.

- ↑ "Law Provides New Regulatory Framework for Space Commerce | RegBlog". 31 December 2015. http://www.regblog.org/2015/12/31/rathz-space-commerce-regulation/.

- ↑ "Text of Declaration of the First Meeting of Equatorial Countries". Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. 2007-01-23. http://www.jaxa.jp/library/space_law/chapter_2/2-2-1-2_e.html.

- ↑ Gangale, Thomas (2006), "Who Owns the Geostationary Orbit?", Annals of Air and Space Law 31, http://pweb.jps.net/~gangale/opsa/ir/WhoOwnsGeostationaryOrbit.htm, retrieved 2011-10-14.

- ↑ "History: Treaties". https://unoosa.org/oosa/en/aboutus/history/treaties.html.

- ↑ "Space Law Treaties and Principles". https://unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties.html.

- ↑ "A History of Space". https://unoosa.org/oosa/en/timeline/index.html.

- ↑ Beyond UNISPACE: It's time for the Moon Treaty. Dennis C. O'Brien. Pace Review. 21 January 2019.

- ↑ "Space Law Treaties and Principles". https://unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties.html.

- ↑ Status of international agreements relating to activities in outer space as at 1 January 2008 United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, 2008

- ↑ "Presidencia de la republica". http://cce.gov.co/prensa/aprobado-proyecto-de-ley-que-ratifica-el-compromiso-de-colombia-con-el-desarrollo-espacial.

Further reading

- Annette Froehlich, et al.: A Fresh View on the Outer Space Treaty. Springer, Vienna 2018, ISBN:978-3-319-70433-3.

External links

- International Institute of Space Law

- Full text of the "Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies" in Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, or Spanish

- Status of International Agreements relating to Activities in Outer Space (list of state parties to treaty), UN Office for Outer Space Affairs

- "The Case for Withdrawing from the 1967 Outer Space Treaty"

- Still Relevant (and Important) After All These Years: The case for supporting the Outer Space Treaty

- Squadron Leader KK Nair's Space: The Frontiers of Modern Defence. Knowledge World Publishers, New Delhi, Chap. 5 "Examining Space Law...", pp. 84–104, available at Google Books.

- Introductory note by Vladimír Kopal, procedural history note and audiovisual material on the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies in the Historic Archives of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

- The Progressive Development of International Space Law by the United Nations—Lecture by Vladimír Kopal] in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

- The Law of Outer Space in the General Legal Field (Commonalities and Particularities)—Lecture by Vladlen Stepanovich Vereshchetin in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

- Humans on Mars and beyond full-text

|

KSF

KSF