Spacecraft magnetometer

Topic: Engineering

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 14 min

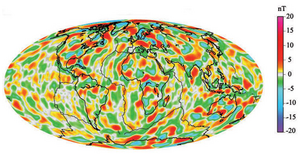

Spacecraft magnetometers are magnetometers used aboard spacecraft and satellites, mostly for scientific investigations, plus attitude sensing. Magnetometers are among the most widely used scientific instruments in exploratory and observation satellites. These instruments were instrumental in mapping the Van Allen radiation belts around Earth after its discovery by Explorer 1, and have detailed the magnetic fields of the Earth, Moon, Sun, Mars, Venus and other planets and moons. There are ongoing missions using magnetometers,[example needed] including attempts to define the shape and activity of Saturn's core.

The first spacecraft-borne magnetometer was placed on the Sputnik 3 spacecraft in 1958 and the most detailed magnetic observations of the Earth have been performed by the Magsat[1] and Ørsted satellites. Magnetometers were taken to the Moon during the later Apollo missions. Many instruments have been used to measure the strength and direction of magnetic field lines around Earth and the Solar System.

Spacecraft magnetometers basically fall into three categories: fluxgate, search-coil and ionized gas magnetometers. The most accurate magnetometer complexes on spacecraft contain two separate instruments, with a helium ionized gas magnetometer used to calibrate the fluxgate instrument for more accurate readings. Many later magnetometers contain small ring-coils oriented at 90° in two dimensions relative to each other forming a triaxial framework for indicating direction of magnetic field.

Magnetometer types

Magnetometers for non-space use evolved from the 19th to mid-20th centuries, and were first employed in spaceflight by Sputnik 3 in 1958. A main constraint on magnetometers in space is the availability of power and mass. Magnetometers fall into 3 major categories: the fluxgate type, search coil and the ionized vapor magnetometers. The newest type is the Overhauser type based on nuclear magnetic resonance technology.

Fluxgate magnetometers

Fluxgate magnetometers are used for their electronic simplicity and low weight. There have been several types of fluxgate used in spacecraft, which vary in two regards. Primarily better readings are obtained with three magnetometers, each pointing in a different direction. Some spacecraft have instead achieved this by rotating the craft and taking readings at 120° intervals, but this creates other issues. The other difference is in the configuration, which is simple and circular.

Magnetometers of this type were equipped on the "Pioneer 0"/Able 1, "Pioneer 1"/Able 2, Ye1.1, Ye1.2, and Ye1.3 missions that failed in 1958 due to launch problems. The Pioneer 1 however did collect data on the Van Allen belts.[2] In 1959 the Soviet "Luna 1"/Ye1.4 carried a three-component magnetometer that passed the Moon en route to a heliocentric orbit at a distance of 6,400 miles (10,300 km), but the magnetic field could not be accurately assessed.[2] Eventually the USSR managed a lunar impact with "Luna 2", a three component magnetometer, finding no significant magnetic field in close approach to the surface.[2] Explorer 10 had an abbreviated 52 hr mission with two fluxgate magnetometers on board. During 1958 and 1959 failure tended to characterize missions carrying magnetometers: 2 instruments were lost on Able IVB alone. In early 1966 the USSR finally placed Luna 10 in orbit around the Moon carrying a magnetometer and was able to confirm the weak nature of the Moon's magnetic field.[2] Venera 4, 5, and 6 also carried magnetometers on their trips to Venus, although they were not placed on the landing craft.

Vector sensors

The majority of early fluxgate magnetometers on spacecraft were made as vector sensors. However, the magnetometer electronics created harmonics which interfered with readings. Properly designed sensors had feedback electronics to the detector that effectively neutralized the harmonics. Mariner 1 and Mariner 2 carried fluxgate-vector sensor devices. Only Mariner 2 survived launch and as it passed Venus on December 14, 1962 it failed to detect a magnetic field around the planet. This was in part due to the distance of the spacecraft from the planet, noise within the magnetometer, and a very weak Venusian magnetic field.[2] Pioneer 6, launched in 1965, is one of 4 Pioneer satellites circling the Sun and relaying information to Earth about solar winds. This spacecraft was equipped with a single vector-fluxgate magnetometer.[2]

Ring core and spherical

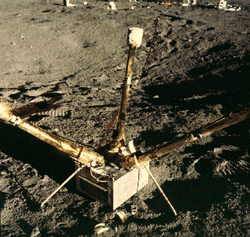

Ring core sensor fluxgate magnetometers began replacing vector sensor magnetometers with the Apollo 16 mission in 1972, where a three axis magnetometer was placed on the Moon. These sensors were used on a number of satellites including Magsat, Voyager, Ulysses, Giotto, AMPTE. The Lunar Prospector-1 uses ring-coil made of these alloys extended away from each other and its spacecraft to look for remnant magnetism in the Moons 'non-magnetic' surface.[3][4]

Properly configured, the magnetometers are capable of measuring magnetic field differences of 1 nT. These devices, with cores about 1 cm in size, were of lower weight than vector sensors. However, these devices were found to have non-linear output with magnetic fields greater than >5000 nT. Later it was discovered that creating a spherical structure with feedback loops wire transverse to the ring in the sphere could negate this effect. These later magnetometers were called spherical fluxgate or compact spherical core (CSC) magnetometers used in the Ørsted satellite. The metal alloys that form the core of these magnetometers has also improved since Apollo-16 mission with latest using advanced molybdenum-permalloy alloys, producing lower noise with more stable output.[5]

Search-coil magnetometer

Search-coil magnetometers, also called induction magnetometers, are wound coils around a core of high magnetic permeability. Search coils concentrate magnetic field lines inside the core along with fluctuations.[6] The benefit of these magnetometers is that they measure alternating magnetic field and so can resolve changes in magnetic fields quickly, many times per second. Following Lenz's law, the voltage is proportional to the time derivative of magnetic flux. The voltage will be amplified by the apparent permeability of the core. This apparent permeability (μa) is defined as:

.

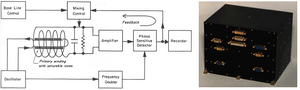

The Pioneer 5 mission finally managed to get a working magnetometer of this type in orbit around the Sun showing that magnetic fields existed between Earth and Venus orbits.[2][7] A single magnetometer was oriented along the plane perpendicular to the spin axis of the spacecraft. Search coil magnetometers have become increasingly more common in Earth observation satellites. A commonly used instrument is the triaxial search-coil magnetometer. Orbiting Geophysical Observatory (OGO missions - OGO-1 to OGO-6)[8][9] The Vela (satellite) mission used this type as part of a package to determine if nuclear weapons evaluation was being conducted outside Earth's atmosphere.[10] In September 1979 a Vela satellite collected evidence of a potential nuclear burst over the South Western Indian Ocean. In 1997 the US created the FAST that was designed to investigate aurora phenomena over the poles.[11] And currently it is investigating magnetic fields at 10 to 30 Earth radii with the THEMIS satellites[12] THEMIS, which stands for Time History of Events and Macroscale Interactions during Substorms is an array of five satellites which hope to gather more precise history of how magnetic storms arise and dissipate.[13]

Ionized gas magnetometers

Heavy metal — scalar

Certain spacecraft, like Magsat, are equipped with scalar magnetometer. The output of these device, often in out frequency, is proportional to the magnetic field. The Magsat and Grm-A1 had cesium-vapor (cesium-133) sensor heads of dual-cell design, this design left two small dead zones. Explorer 10 (P14) was equipped with a rubidium vapor magnetometer, presumably a scalar magnetometer since the spacecraft also had a fluxgate. The magnetometer was fouled accidentally which caused it to overheat, it worked for a period of time but 52 h into the mission transmission went dead and was not regained.[14] Ranger 1 and 2 carried a rubidium vapor magnetometer, failed to reach lunar orbit.[2]

Helium

This type of magnetometer depends on the variation in helium absorptivity, when excited, polarized infrared light with an applied magnetic field.[15] A low field vector-helium magnetometer was equipped on the Mariner 4 spacecraft to Mars like the Venus probe a year earlier, no magnetic field was detected.[16] Mariner 5 used a similar device For this experiment a low-field helium magnetometer was used to obtain triaxial measurements of interplanetary and Venusian magnetic fields. Similar in accuracy to the triaxial flux-gated magnetometers this device produced more reliable data.

Other types

Overhauser magnetometer provides extremely accurate measurements of the strength of the magnetic field. The Ørsted satellite uses this type of magnetometer to map the magnetic fields over the surface of the Earth.

On the Vanguard 3 mission (1959) a proton processional magnetometer was used to measure geomagnetic fields. The proton source was hexane.[17]

Configurations of magnetometers

Unlike ground-based magnetometers that can be oriented by the user to determine the direction of magnetic field, in space the user is linked by telecommunications to a satellite traveling at 25,000 km per hour. The magnetometers used need to give an accurate reading quickly to be able to deduce magnetic fields. Several strategies can be employed, it is easier to rotate a space craft about its axis than to carry the weight of an additional magnetometer. Another strategy is to increase the size of the rocket, or make the magnetometer lighter and more effective. One of the problems, for example in studying planets with low magnetic fields like Venus, does require more sensitive equipment. The equipment has necessarily needed to evolve for today's modern task. Ironically satellites launched more the 20 years ago still have working magnetometers in places where it would take decades to reach today, at the same time the latest equipment is being used to analyze changes in the Earth here at home.

Uniaxial

These simple fluxgate magnetometers were used on many missions. On Pioneer 6 and Injun 1 the magnetometers were mounted to a bracket external to the space craft and readings were taken as the spacecraft rotated every 120°.[18] Pioneer 7 and Pioneer 8 are configured similarly.[19] The fluxgate on Explorer 6 was mounted along the spin axis to verify spacecraft tracking magnetic field lines. Search coil magnetometers were used on Pioneer 1, Explorer 6, Pioneer 5, and Deep Space 1.

Diaxial

A two axis magnetometer was mounted to the ATS-1 (Applications Technology Satellite).[20] One sensor was on a 15 cm boom and the other on the spacecraft's spin axis (Spin stabilized satellite). The Sun was used to sense the position of the boom mounted device, and triaxial vector measurements could be calculated. Compared to other boom mounted magnetometers, this configuration had considerable interference. With this spacecraft, the sun induced magnetic oscillations and this allowed the continued use of the magnetometer after the Sun sensor failed. Explorer 10 had two fluxgate magnetometers but is technically classified as a dual technique since it also had a rubidium vapor magnetometer.

Triaxial

The Sputnik-3 had a vector fluxgate magnetometer, however because the orientation of the spacecraft could not be determined the direction vector for the magnetic field could not be determined. Three axis magnetometers were used on Luna 1, Luna 2, Pioneer Venus, Mariner 2, Venera 1, Explorer 12, Explorer 14, and Explorer 15. Explorer 33 was 'to be' the first US spacecraft to enter stable orbit around the Moon was equipped with the most advanced magnetometer, a boom-mounted triaxial fluxgate (GFSC) magnetometer of the early-vector type. It had a small range but was accurate to a resolution of 0.25 nT.[21] However, after a rocket failure it was left in a highly elliptical orbit around Earth that orbited through the electro/magnetic tail.[22]

The Pioneer 9 and Explorer 34 used a configuration similar to Explorer 33 to survey the magnetic field within Earth's solar orbit. Explorer 35 was the first of its type to enter stable orbit around the Moon, this proved important because with the sensitive triaxial magnetometer on board, it was found the Moon effectively had no magnetic field, no radiation belt, and solar winds directly impacted the Moon.[2] Lunar Prospector surveyed for surface magnetism around the Moon (1998–99), using the triaxial (extended) magnetometers. With Apollo 12 improved magnetometers were placed on the Moon as part of the Lunar Module/Apollo Lunar Surface Experiments Package

(ALSEP).[23][24] The magnetometer continued to work several months after that return module departed. As part of the Apollo 14 ALSEP, there was a portable magnetometer.

The first use of the three axis ring-coil magnetometer was on the Apollo 16 Moon mission. Subsequently, it was used on the Magsat. The MESSENGER mission has triaxial ring-coil magnetometer with a range of +/- 1000 mT and a sensitivity of 0.02 mT, still in progress, the mission is designed to get detailed information about Mercurian magnetosphere.[25] The first use of spherical magnetometer in three axis configuration was on the Ørsted satellite.

Dual technique

Each type of magnetometer has its own built in 'weakness'. This can result from the design of the magnetometer to the way the magnetometer interacts with the spacecraft, radiation from the Sun, resonances, etc. Using completely different design is a way to measure which readings are the result of natural magnetic fields and the sum of magnetic fields altered by spacecraft systems. In addition each type has its strengths. The fluxgate type is relatively good at providing data that finds magnetic sources. One of the first Dual technique systems was the abbreviated Explorer 10 mission which used a rubidium vapor and biaxial fluxgate magnetometers. Vector helium is better at tracking magnetic field lines and as a scalar magnetometer. Cassini spacecraft used a Dual Technique Magnetometer. One of these devices is the ring-coil vector fluxgate magnetometer (RCFGM). The other device is a vector/scalar helium magnetometer.[26] The RCFGM is mounted 5.5 m out on an 11 m boom with the helium device at the end.

Explorer 6 (1959) used a search coil magnetometer to measure the gross magnetic field of the Earth and vector fluxgate.,[27] however because of induced magnetism in the space craft the fluxgate sensor became saturated and did not send data. Future missions would attempt to place magnetometers further away from the space craft.

Magsat Earth geological satellite was also Dual Technique. This satellite and Grm-A1 carried a scalar cesium vapor magnetometer and vector fluxgate magnetometers.[28][29] The Grm-A1 satellite carrier the magnetometer on 4 meter boom. This particular spacecraft was designed to hold in a precised equi-gravitational orbit, while taking measurements.[30] For purposes similar to Magsat, the Ørsted satellite, also used a dual technique system. The Overhauser magnetometer is situated at the end of an 8 meter long boom, in order to minimize disturbances from the satellite's electrical systems. The CSC fluxgate magnetometer is located inside the body and associated with a star tracking device. One of the greater accomplishments of the two missions, the Magsat and Ørsted missions happen to capture a period of great magnetic field change, with the potential of a loss of dipole, or pole reversal.[31][32]

By mounting

The simplest magnetometer implementations are mounted directly to their vehicles. However, this places the sensor close to potential interferences such as vehicle currents and ferrous materials. For relatively insensitive work, such as "compasses" (attitude sensing) in Low Earth orbit, this may be sufficient.

The most sensitive magnetometer instruments are mounted on long booms, deployed away from the craft (e.g., the Voyagers, Cassini). Many contaminant fields then decrease strongly with distance, while background fields appear unchanged. Two magnetometers may be mounted, one only partially down the boom. The vehicle body's fields will then appear different at the two distances, while background fields may or may not change significantly over such scales. Magnetometer booms for vector instruments must be rigid, to prevent additional flexing motions from appearing in the data.

Some vehicles mount magnetometers on simpler, existing appendages, such as specially designed solar arrays (e.g., Mars Global Surveyor, Juno, MAVEN). This saves the cost and mass of a separate boom. However, a solar array must have its cells carefully implemented and tested to avoid becoming a contaminating field.

Examples

- FIELDS, on Parker Solar Probe launched 2018

- Magnetometer, on Juno Jupiter Orbiter, launched 2011 arrived at Jupiter 2018

- Interior Characterization of Europa using Magnetometry

See also

References

- ↑ History of Vector Magnetometers in Space

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Asif A. Siddiqi 1958. Deep space chronicle. A Chronology of Deep Space and Planetary Probes 1958–2000 History. NASA.

- ↑ Lunar Prospector Magnetometer (MAG) National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ "Improved gravity field of the moon from lunar prospector". Science 281 (5382): 1476–80. September 1998. doi:10.1126/science.281.5382.1476. PMID 9727968. Bibcode: 1998Sci...281.1476K.

- ↑ The MGS Magnetometer and Electron Reflectometer Mars global surveyor, NASA

- ↑ Search Coil Magnetometers (SCM) THEMIS mission. NASA

- ↑ Magnetometer - Pioneer 5 mission

- ↑ Search coil magnetometer - OGO1 mission, National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Frandsen, A. M. A., Holzer, R. E., and Smith, E. J. OGO Search Coil Magnetometer Experiments. (1969) IEEE Trans. Geosci. Electron. GE-7, 61-74.

- ↑ Search coil magnetometers - Vela2A mission National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Tri-Axial Fluxgate and Search-coil Magnetometers - FAST Mission National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Search coil magnetometer - Themis-A National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Themis-A National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ RB-Vapor and Fluxgate Magnetometers National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Triaxial Low Field Helium Magnetometer - Mariner 5 mission National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Helium Magnetometer-Mariner 4 mission National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Proton Processional Magnetometer National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Uniaxial Fluxgate Magnetometer - Pioneer 6 National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Single-Axis Magnetometer-Pioneer 9 National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Biaxial Fluxgate Magnetometer - Application Technology Satellite -1 (ATS-1) National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ GFSC Magnetometer - Explorer 33 National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Behannon KW. Mapping of the Earth's Bow Shock and Magnetic Tail by Explorer 33. 1968. J. Geophys. Res. 73: 907-930

- ↑ Lunar Surface Magnetometer - Apollo-12 Lunar module National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Lunar Surface Magnetometer National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ MESSENGER Space Science Data Center, NASA]

- ↑ SPACECRAFT - Cassini Orbiter Instruments - MAG

- ↑ Experiments Explorer 6 National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Scalar Magnetometer Magsat mission National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ Vector Magnetometer Magsat mission National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ GRM-A1 National Space Science Data Center, NASA

- ↑ "Small-scale structure of the geodynamo inferred from Oersted and Magsat satellite data". Nature 416 (6881): 620–3. April 2002. doi:10.1038/416620a. PMID 11948347. Bibcode: 2002Natur.416..620H. http://orbit.dtu.dk/en/publications/smallscale-structure-of-the-geodynamo-inferred-from-oersted-and-magsat-satellite-data(17764f14-49bb-4a72-901f-f22800e2b8f2).html.

- ↑ NASA AND USGS MAGNETIC DATABASE "ROCKS" THE WORLD NASA Web Feature, NASA

|

KSF

KSF