Table of Contents

- 1 Motivation

- 2 Preliminaries, notation, and basic notions

- 3 Set theoretic properties and constructions relevant to topology

- 4 Convergence, limits, and cluster points

- 5 Filters and nets

- 6 Topologies and prefilters

- 7 Examples of applications of prefilters

- 8 See also

- 9 Notes

- 10 Citations

- 11 References Categories

- Not empty: – just as since is always a neighborhood of (and of anything else that it contains);

- Does not contain the empty set: – just as no neighborhood of is empty;

- Closed under finite intersections: If – just as the intersection of any two neighborhoods of is again a neighborhood of ;

- Upward closed: If then – just as any subset of that contains a neighborhood of will necessarily be a neighborhood of (this follows from and the definition of "a neighborhood of ").

- Proper or nondegenerate if Otherwise, if then it is called improper[17] or degenerate.

- Directed downward[15] if whenever then there exists some such that

- This property can be characterized in terms of directedness, which explains the word "directed": A binary relation on is called (upward) directed if for any two there is some satisfying Using in place of gives the definition of directed downward whereas using instead gives the definition of directed upward. Explicitly, is directed downward (resp. directed upward) if and only if for all there exists some "greater" such that (resp. such that ) − where the "greater" element is always on the right hand side, − which can be rewritten as (resp. as ).

- Closed under finite intersections (resp. unions) if the intersection (resp. union) of any two elements of is an element of

- If is closed under finite intersections then is necessarily directed downward. The converse is generally false.

- Upward closed or Isotone in [6] if or equivalently, if whenever and some set satisfies Similarly, is downward closed if An upward (respectively, downward) closed set is also called an upper set or upset (resp. a lower set or down set).

- The family which is the upward closure of is the unique smallest (with respect to ) isotone family of sets over having as a subset.

- Ideal[17][18] if is downward closed and closed under finite unions.

- Dual ideal on [19] if is upward closed in and also closed under finite intersections. Equivalently, is a dual ideal if for all [20]

- Explanation of the word "dual": A family is a dual ideal (resp. an ideal) on if and only if the dual of which is the family is an ideal (resp. a dual ideal) on In other words, dual ideal means "dual of an ideal". The dual of the dual is the original family, meaning [17]

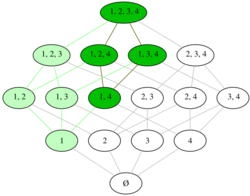

- Filter on [19][8] if is a proper dual ideal on That is, a filter on is a non−empty subset of that is closed under finite intersections and upward closed in Equivalently, it is a prefilter that is upward closed in In words, a filter on is a family of sets over that (1) is not empty (or equivalently, it contains ), (2) is closed under finite intersections, (3) is upward closed in and (4) does not have the empty set as an element.

- Warning: Some authors, particularly algebrists, use "filter" to mean a dual ideal; others, particularly topologists, use "filter" to mean a proper/non–degenerate dual ideal.[21] It is recommended that readers always check how "filter" is defined when reading mathematical literature. However, the definitions of "ultrafilter," "prefilter," and "filter subbase" always require non-degeneracy. This article uses Henri Cartan's original definition of "filter",[1][22] which required non–degeneracy.

- The power set is the one and only dual ideal on that is not also a filter. Excluding from the definition of "filter" in topology has the same benefit as excluding from the definition of "prime number": it obviates the need to specify "non-degenerate" (the analog of "non-unital" or "non-") in many important results, thereby making their statements less awkward.

- Prefilter or filter base[8][23] if is proper and directed downward. Equivalently, is called a prefilter if its upward closure is a filter. It can also be defined as any family that is equivalent to some filter.[9] A proper family is a prefilter if and only if [9] A family is a prefilter if and only if the same is true of its upward closure.

- If is a prefilter then its upward closure is the unique smallest (relative to ) filter on containing and it is called the filter generated by A filter is said to be generated by a prefilter if in which is called a filter base for

- Unlike a filter, a prefilter is not necessarily closed under finite intersections.

- π–system if is closed under finite intersections. Every non–empty family is contained in a unique smallest π–system called the π–system generated by which is sometimes denoted by It is equal to the intersection of all π–systems containing and also to the set of all possible finite intersections of sets from :

- A π–system is a prefilter if and only if it is proper. Every filter is a proper π–system and every proper π–system is a prefilter but the converses do not hold in general.

- A prefilter is equivalent to the π–system generated by it and both of these families generate the same filter on

- Filter subbase[8][24] and centered[9] if and satisfies any of the following equivalent conditions:

- has the finite intersection property, which means that the intersection of any finite family of (one or more) sets in is not empty; explicitly, this means that whenever then

- The π–system generated by is proper; that is,

- The π–system generated by is a prefilter.

- is a subset of some prefilter.

- is a subset of some filter.[10]

- Assume that is a filter subbase. Then there is a unique smallest (relative to ) filter containing called the filter generated by , and is said to be a filter subbase for this filter. This filter is equal to the intersection of all filters on that are supersets of The π–system generated by denoted by will be a prefilter and a subset of Moreover, the filter generated by is equal to the upward closure of meaning [9] However, if and only if is a prefilter (although is always an upward closed filter subbase for ).

- A –smallest (meaning smallest relative to ) prefilter containing a filter subbase will exist only under certain circumstances. It exists, for example, if the filter subbase happens to also be a prefilter. It also exists if the filter (or equivalently, the π–system) generated by is principal, in which case is the unique smallest prefilter containing Otherwise, in general, a –smallest prefilter containing might not exist. For this reason, some authors may refer to the π–system generated by as the prefilter generated by However, if a –smallest prefilter does exist (say it is denoted by ) then contrary to usual expectations, it is not necessarily equal to "the prefilter generated by " (that is, is possible). And if the filter subbase happens to also be a prefilter but not a π-system then unfortunately, "the prefilter generated by this prefilter" (meaning ) will not be (that is, is possible even when is a prefilter), which is why this article will prefer the accurate and unambiguous terminology of "the π–system generated by ".

- Subfilter of a filter and that is a superfilter of [17][25] if is a filter and where for filters,

- Importantly, the expression "is a superfilter of" is for filters the analog of "is a subsequence of". So despite having the prefix "sub" in common, "is a subfilter of" is actually the reverse of "is a subsequence of." However, can also be written which is described by saying " is subordinate to " With this terminology, "is subordinate to" becomes for filters (and also for prefilters) the analog of "is a subsequence of,"[26] which makes this one situation where using the term "subordinate" and symbol may be helpful.

- The singleton set is called the indiscrete or trivial filter on [27][28] It is the unique minimal filter on because it is a subset of every filter on ; however, it need not be a subset of every prefilter on

- The dual ideal is also called the degenerate filter on [20] (despite not actually being a filter). It is the only dual ideal on that is not a filter on

- If is a topological space and then the neighborhood filter at is a filter on By definition, a family is called a neighborhood basis (resp. a neighborhood subbase) at if and only if is a prefilter (resp. is a filter subbase) and the filter on that generates is equal to the neighborhood filter The subfamily of open neighborhoods is a filter base for Both prefilters also form a bases for topologies on with the topology generated being coarser than This example immediately generalizes from neighborhoods of points to neighborhoods of non–empty subsets

- is an elementary prefilter[29] if for some sequence of points

- is an elementary filter or a sequential filter on [30] if is a filter on generated by some elementary prefilter. The filter of tails generated by a sequence that is not eventually constant is necessarily not an ultrafilter.[31] Every principal filter on a countable set is sequential as is every cofinite filter on a countably infinite set.[20] The intersection of finitely many sequential filters is again sequential.[20]

- The set of all cofinite subsets of (meaning those sets whose complement in is finite) is proper if and only if is infinite (or equivalently, is infinite), in which case is a filter on known as the Fréchet filter or the cofinite filter on [28][27] If is finite then is equal to the dual ideal which is not a filter. If is infinite then the family of complements of singleton sets is a filter subbase that generates the Fréchet filter on As with any family of sets over that contains the kernel of the Fréchet filter on is the empty set:

- The intersection of all elements in any non–empty family is itself a filter on called the infimum or greatest lower bound of which is why it may be denoted by Said differently, Because every filter on has as a subset, this intersection is never empty. By definition, the infimum is the finest/largest (relative to ) filter contained as a subset of each member of [28]

- If are filters then their infimum in is the filter [9] If are prefilters then is a prefilter that is coarser than both (that is, ); indeed, it is one of the finest such prefilters, meaning that if is a prefilter such that then necessarily [9] More generally, if are non−empty families and if then and is a greatest element of [9]

- Let and let The supremum or least upper bound of denoted by is the smallest (relative to ) dual ideal on containing every element of as a subset; that is, it is the smallest (relative to ) dual ideal on containing as a subset. This dual ideal is where is the π–system generated by As with any non–empty family of sets, is contained in some filter on if and only if it is a filter subbase, or equivalently, if and only if is a filter on in which case this family is the smallest (relative to ) filter on containing every element of as a subset and necessarily

- Let and let

The supremum or least upper bound of denoted by if it exists, is by definition the smallest (relative to ) filter on containing every element of as a subset.

If it exists then necessarily [28] (as defined above) and will also be equal to the intersection of all filters on containing

This supremum of exists if and only if the dual ideal is a filter on

The least upper bound of a family of filters may fail to be a filter.[28] Indeed, if contains at least 2 distinct elements then there exist filters for which there does not exist a filter that contains both

If is not a filter subbase then the supremum of does not exist and the same is true of its supremum in but their supremum in the set of all dual ideals on will exist (it being the degenerate filter ).[20]

- If are prefilters (resp. filters on ) then is a prefilter (resp. a filter) if and only if it is non–degenerate (or said differently, if and only if mesh), in which case it is one of the coarsest prefilters (resp. the coarsest filter) on that is finer (with respect to ) than both this means that if is any prefilter (resp. any filter) such that then necessarily [9] in which case it is denoted by [20]

- Let and let which makes a prefilter and a filter subbase that is not closed under finite intersections. Because is a prefilter, the smallest prefilter containing is The π–system generated by is In particular, the smallest prefilter containing the filter subbase is not equal to the set of all finite intersections of sets in The filter on generated by is All three of the π–system generates, and are examples of fixed, principal, ultra prefilters that are principal at the point is also an ultrafilter on

- Let be a topological space, and define where is necessarily finer than [32] If is non–empty (resp. non–degenerate, a filter subbase, a prefilter, closed under finite unions) then the same is true of If is a filter on then is a prefilter but not necessarily a filter on although is a filter on equivalent to

- The set of all dense open subsets of a (non–empty) topological space is a proper π–system and so also a prefilter. If the space is a Baire space, then the set of all countable intersections of dense open subsets is a π–system and a prefilter that is finer than If (with ) then the set of all such that has finite Lebesgue measure is a proper π–system and a free prefilter that is also a proper subset of The prefilters and are equivalent and so generate the same filter on The prefilter is properly contained in, and not equivalent to, the prefilter consisting of all dense open subsets of Since is a Baire space, every countable intersection of sets in is dense in (and also comeagre and non–meager) so the set of all countable intersections of elements of is a prefilter and π–system; it is also finer than, and not equivalent to,

- Ultra[8][33] if and any of the following equivalent conditions are satisfied:

- For every set there exists some set such that (or equivalently, such that ).

- For every set there exists some set such that

- This characterization of " is ultra" does not depend on the set so mentioning the set is optional when using the term "ultra."

- For every set (not necessarily even a subset of ) there exists some set such that

- Ultra prefilter[8][33] if it is a prefilter that is also ultra. Equivalently, it is a filter subbase that is ultra. A prefilter is ultra if and only if it satisfies any of the following equivalent conditions:

- is maximal in with respect to which means that

-

- Although this statement is identical to that given below for ultrafilters, here is merely assumed to be a prefilter; it need not be a filter.

- is ultra (and thus an ultrafilter).

- is equivalent to some ultrafilter.

- A filter subbase that is ultra is necessarily a prefilter. A filter subbase is ultra if and only if it is a maximal filter subbase with respect to (as above).[17]

- Ultrafilter on [8][33] if it is a filter on that is ultra. Equivalently, an ultrafilter on is a filter that satisfies any of the following equivalent conditions:

- is generated by an ultra prefilter.

- For any [17]

- This condition can be restated as: is partitioned by and its dual

- For any if then (a filter with this property is called a prime filter).

- This property extends to any finite union of two or more sets.

- is a maximal filter on ; meaning that if is a filter on such that then necessarily (this equality may be replaced by ).

- If is upward closed then So this characterization of ultrafilters as maximal filters can be restated as:

- Because subordination is for filters the analog of "is a subnet/subsequence of" (specifically, "subnet" should mean "AA–subnet," which is defined below), this characterization of an ultrafilter as being a "maximally subordinate filter" suggests that an ultrafilter can be interpreted as being analogous to some sort of "maximally deep net" (which could, for instance, mean that "when viewed only from " in some sense, it is indistinguishable from its subnets, as is the case with any net valued in a singleton set for example),[note 5] which is an idea that is actually made rigorous by ultranets. The ultrafilter lemma is then the statement that every filter ("net") has some subordinate filter ("subnet") that is "maximally subordinate" ("maximally deep").

- (1) (2) the π–system generated by and (3) the filter generated by

- Free[7] if or equivalently, if this can be restated as

- A filter is free if and only if is infinite and contains the Fréchet filter on as a subset.

- Fixed if in which case, is said to be fixed by any point

- Any fixed family is necessarily a filter subbase.

- Principal[7] if

- A proper principal family of sets is necessarily a prefilter.

- Discrete or Principal at [27] if

- The principal filter at is the filter A filter is principal at if and only if

- Countably deep if whenever is a countable subset then [20]

- is fixed, or equivalently, not free, meaning

- is principal, meaning

- Some element of is a finite set.

- Some element of is a singleton set.

- is principal at some point of which means for some

- does not contain the Fréchet filter on

- is sequential.[20]

- Definition: Every contains some Explicitly, this means that for every there is some such that (thus holds).

- Said more briefly in plain English, if every set in is larger than some set in Here, a "larger set" means a superset.

-

- In words, states exactly that is larger than some set in The equivalence of (a) and (b) follows immediately.

- which is equivalent to ;

- ;

- which is equivalent to ;

- [6]

- So in this case, this definition of " is finer than " would be identical to the topological definition of "finer" had been topologies on

- The upward closures of are equal.

- Not empty

- Proper (that is, is not an element)

- Moreover, any two degenerate families are necessarily equivalent.

- Filter subbase

- Prefilter

- In which case generate the same filter on (that is, their upward closures in are equal).

- Free

- Principal

- Ultra

- Is equal to the trivial filter

- In words, this means that the only subset of that is equivalent to the trivial filter is the trivial filter. In general, this conclusion of equality does not extend to non−trivial filters (one exception is when both families are filters).

- Meshes with

- Is finer than

- Is coarser than

- Is equivalent to

- ;

- the π–system generated by ;

- the filter on generated by ;

- is a prefilter;

- is a prefilter;

- ;

- meshes with

- the prefilter of all open balls centered at the origin, where

- the prefilter of all closed balls centered at the origin, where This prefilter is equivalent to the one above.

- the prefilter where is a union of spheres centered at the origin having progressively smaller radii. This family consists of the sets as ranges over the positive integers.

- any of the families above but with the radius ranging over (or over any other positive decreasing sequence) instead of over all positive reals.

- Drawing or imagining any one of these sequences of sets when has dimension suggests that intuitively, these sets "should" converge to the origin (and indeed they do). This is the intuition that the above definition of a "convergent prefilter" make rigorous.

- converges to

- converges to the set

- converges to

- There exists a family equivalent to that converges to

- clusters at

- clusters at the set

- The family generated by clusters at

- There exists a family equivalent to that clusters at

- [42]

- for every neighborhood of

- If is a filter on then for every neighborhood

- There exists a prefilter subordinate to (that is, ) that converges to

- This is the filter equivalent of " is a cluster point of a sequence if and only if there exists a subsequence converging to

- In particular, if is a cluster point of a prefilter then is a prefilter subordinate to that converges to

- The limit inferior of is the infimum of the set of all cluster points of

- The limit superior of is the supremum of the set of all cluster points of

- is a convergent prefilter if and only if its limit inferior and limit superior agree; in this case, the value on which they agree is the limit of the prefilter.

- Definition: For every there exists some such that if

- For every there exists some such that the tail of starting at is contained in (that is, such that ).

- For every there exists some such that

- that is, the prefilter converges to

- Definition: For every and every there exists some such that

- For every and every the tail of starting at intersects (that is, ).

- For every and every

- mesh (by definition of "mesh").

- is a cluster point of

- is a cluster point of if and only if is a cluster point of

- Suppose is a prefilter such that

- If [proof 1]

- This is the analog of "if a sequence converges to then so does every subsequence."

- If is a cluster point of then is a cluster point of

- This is the analog of "if is a cluster point of some subsequence, then is a cluster point of the original sequence."

- If [proof 1]

- if and only if for any finer prefilter there exists some even more fine prefilter such that [43]

- This is the analog of "a sequence converges to if and only if every subsequence has a sub–subsequence that converges to "

- is a cluster point of if and only if there exists some finer prefilter such that

- This is the analog of the following false statement: " is a cluster point of a sequence if and only if it has a subsequence that converges to " (that is, if and only if is a subsequential limit).

- The analog for sequences is false since there is a Hausdorff topology on and a sequence in this space (both defined here[note 7][51]) that clusters at but that also does not have any subsequence that converges to [52]

- is a Willard–subnet of or a subnet in the sense of Willard if there exists an order–preserving map such that is cofinal in

- is a Kelley–subnet of or a subnet in the sense of Kelley if there exists a map such that and whenever is eventual in then is eventual in

- is an AA–subnet of or a subnet in the sense of Aarnes and Andenaes if any of the following equivalent conditions are satisfied:

- If is eventual in is eventual in

- For any subset mesh, then so do

- For any subset

- Example: If and is a constant sequence and if and then is an AA-subnet of but it is neither a Willard-subnet nor a Kelley-subnet of

- is a limit point of a prefilter on Explicitly: there exists a prefilter such that [50]

- is a limit point of a filter on [44]

- There exists a prefilter such that

- The prefilter meshes with the neighborhood filter Said differently, is a cluster point of the prefilter

- The prefilter meshes with some (or equivalently, with every) filter base for (that is, with every neighborhood basis at ).

- is a limit points of

- There exists a prefilter such that [50]

- is a closed subset of

- If is a prefilter on such that then

- If is a prefilter on such that is an accumulation points of then [50]

- If is such that the neighborhood filter meshes with then

- is a Hausdorff space.

- Every prefilter on converges to at most one point in [8]

- The above statement but with the word "prefilter" replaced by any one of the following: filter, ultra prefilter, ultrafilter.[8]

- is a compact space.

- Every ultrafilter on converges to at least one point in [56]

- That this condition implies compactness can be proven by using only the ultrafilter lemma. That compactness implies this condition can be proven without the ultrafilter lemma (or even the axiom of choice).

- The above statement but with the word "ultrafilter" replaced by "ultra prefilter".[8]

- For every filter there exists a filter such that and converges to some point of

- The above statement but with each instance of the word "filter" replaced by: prefilter.

- Every filter on has at least one cluster point in [56]

- That this condition is equivalent to compactness can be proven by using only the ultrafilter lemma.

- The above statement but with the word "filter" replaced by "prefilter".[8]

- Alexander subbase theorem: There exists a subbase such that every cover of by sets in has a finite subcover.

- That this condition is equivalent to compactness can be proven by using only the ultrafilter lemma.

- is continuous at

- Definition: For every neighborhood of there exists some neighborhood of such that

- [52]

- If is a filter on such that then

- The above statement but with the word "filter" replaced by "prefilter".

- is continuous.

- If is a prefilter on such that then [52]

- If is a limit point of a prefilter then is a limit point of

- Any one of the above two statements but with the word "prefilter" replaced by "filter".

- For each the discrete ultrafilter at is an element of

- If is a subset of a proper filter then

- If and if each member of intersects each member of then

- A map is closed (meaning it sends closed sets to closed subset of ) if and only if whenever then

- In comparison, is continuous if and only if whenever then

ProofAssume is closed and If then is in the open set so that implies that is eventually empty and thus that in So assume and let be an open neighborhood of in It remains to show that for some index Since is closed, is an open neighborhood of in so there must exists some index such that This implies where the right hand side is a subset of as desired.

For the converse, assume that implies Let be closed and assume it is not empty. Let be a net in (meaning for all ) and let be such that It remains to show that The hypotheses guarantee that The fact that every fiber is not empty and that these fibers converge to imply that Since is open, were it true that then there would exist some index such that which is impossible since for every index Thus so there is some which proves that

- A map is open (meaning it sends open sets to open subset of ) if and only if whenever is a point in and is a net that clusters at then clusters at

- In comparison, is continuous if and only if whenever is a net that clusters at a point then clusters at

ProofFor the non-trivial direction, suppose that is not an open map. Pick an open subset such that is not open in where non-openness means that there is some point such that is not a neighborhood of in Explicitly, this means that for every neighborhood of in which guarantees the existence of some Let denote the neighborhood filter of in and direct it by to make into a net that converges to in which implies that clusters at in Because there exists But does not clusters at since for every

The alternative proof below is demonstrate how a prefilter can be used to construct a net of sets, which in turn can be used to construct a net of points.

Because is not a neighborhood of the family does not contain the empty set. If and are neighborhood of then the intersections and both equal which belongs to (since ) and is thus not empty. This shows that is a π-system and that it meshes with the neighborhood filter In particular, is a prefilter that clusters at Moreover, because every contains as a subset, which proves that

Pick as before. The set is thus a neighborhood of that is disjoint from for every neighborhood Thus does not cluster at even though the prefilter clusters at

Conclusion using nets of sets: Direct the above prefilter by so that the identity map becomes a net of sets. This net clusters at (respectively, converges to) because this is true of But because does not cluster at neither does the net of preimages

Conclusion using nets of points: For every pick a point Then is a net that converges to in (because this is true of the net of sets ), which implies that clusters at in But does not clusters at since for every

- A map is open if and only if whenever then any closed subset of that contains [note 8] will necessarily also contain

- In comparison, by the closure characterization of continuity, is continuous if and only if whenever then any closed subset of that contains will necessarily also contain

ProofIf is any subset then it is readily verified that This implies that a map is open if and only if whenever is closed in then is closed in This characterization of "open map" combined with the convergent net characterization of closed sets produces the desired conclusion: is open if and only if whenever and is a closed subset of that contains then necessarily

- A continuous surjection is a quotient map if and only if whenever then any saturated closed subset of that contains will necessarily also contain (A set is saturated if )

- A subset is closed in if and only if for every point and every net of subsets of that is not eventually empty, if then

- A map is continuous if and only if whenever and are sets or points in such that then

Proof

The proof is essentially identical to the usual proof involving only nets of points. One direction (that whose conclusion is that is continuous) only requires consideration of nets of points and so it is omitted. So suppose that the map is continuous and that Let be an open neighborhood of in Then is an open neighborhood of in so there exists some index such that Thus as desired.

- A map is continuous if and only if whenever is a net of sets or points in that clusters at (respectively, converges to) some given point or subset of then clusters at (respectively, converges to) in

- Lower case letters for elements

- Upper case letters for subsets

- Upper case calligraphy letters for subsets (or equivalently, for elements such as prefilters).

- Upper case double–struck letters for subsets

- Closure in : belongs to the closure of if and only if

- Neighborhoods in : is a neighborhood of if and only if there exists some such that (that is, such that for all ).

- Characterizations of the category of topological spaces

- Convergence space – Generalization of the notion of convergence that is found in general topology

- Filtration (mathematics)

- Filtration (probability theory) – Model of information available at a given point of a random process

- Fréchet filter

- Generic filter

- Ideal (set theory) – Non-empty family of sets that is closed under finite unions and subsets

- ↑ Sequences and nets in a space are maps from directed sets like the natural number, which in general maybe entirely unrelated to the set and so they, and consequently also their notions of convergence, are not intrinsic to

- ↑ Technically, any infinite subfamily of this set of tails is enough to characterize this sequence's convergence. But in general, unless indicated otherwise, the set of all tails is taken unless there is some reason to do otherwise.

- ↑ Indeed, net convergence is defined using neighborhood filters while (pre)filters are directed sets with respect to so it is difficult to keep these notions completely separate.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 The terms "Filter base" and "Filter" are used if and only if

- ↑ For instance, one sense in which a net could be interpreted as being "maximally deep" is if all important properties related to (such as convergence for example) of any subnet is completely determined by in all topologies on In this case and its subnet become effectively indistinguishable (at least topologically) if one's information about them is limited to only that which can be described in solely in terms of and directly related sets (such as its subsets).

- ↑ The set equality holds more generally: if the family of sets then the family of tails of the map (defined by ) is equal to

- ↑ The topology on is defined as follows: Every subset of is open in this topology and the neighborhoods of are all those subsets containing for which there exists some positive integer such that for every integer contains all but at most finitely many points of For example, the set is a neighborhood of Any diagonal enumeration of furnishes a sequence that clusters at but possess not convergent subsequence. An explicit example is the inverse of the bijective Hopcroft and Ullman pairing function which is defined by

- ↑ A set contains means that for every index

- ↑ As a side note, had the definitions of "filter" and "prefilter" not required propriety then the degenerate dual ideal would have been a prefilter on so that in particular, with

- ↑ This is because the inclusion is the only one in the sequence below whose proof uses the defining assumption that

- ↑ By definition, Since transitivity implies

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Cartan 1937a.

- ↑ Wilansky 2013, p. 44.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Schechter 1996, pp. 155–171.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Fernández-Bretón, David J. (2021-12-22). "Using Ultrafilters to Prove Ramsey-type Theorems". The American Mathematical Monthly (Informa UK Limited) 129 (2): 116–131. doi:10.1080/00029890.2022.2004848. ISSN 0002-9890.

- ↑ Howes 1995, pp. 83–92.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Dolecki & Mynard 2016, pp. 27–29.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Dolecki & Mynard 2016, pp. 33–35.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 Narici & Beckenstein 2011, pp. 2–7.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 Császár 1978, pp. 53–65.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Bourbaki 1989, p. 58.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Schubert 1968, pp. 48–71.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Narici & Beckenstein 2011, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Dugundji 1966, pp. 215–221.

- ↑ Dugundji 1966, p. 215.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Wilansky 2013, p. 5.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Dolecki & Mynard 2016, p. 10.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Schechter 1996, pp. 100–130.

- ↑ Császár 1978, pp. 82–91.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Dugundji 1966, pp. 211–213.

- ↑ 20.00 20.01 20.02 20.03 20.04 20.05 20.06 20.07 20.08 20.09 Dolecki & Mynard 2016, pp. 27–54.

- ↑ Schechter 1996, p. 100.

- ↑ Cartan 1937b.

- ↑ Császár 1978, pp. 53–65, 82–91.

- ↑ Arkhangel'skii & Ponomarev 1984, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Joshi 1983, p. 244.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Dugundji 1966, p. 212.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Wilansky 2013, pp. 44–46.

- ↑ 28.00 28.01 28.02 28.03 28.04 28.05 28.06 28.07 28.08 28.09 28.10 28.11 28.12 28.13 28.14 28.15 28.16 28.17 28.18 28.19 28.20 28.21 28.22 28.23 Bourbaki 1989, pp. 57–68.

- ↑ Castillo, Jesus M. F.; Montalvo, Francisco (January 1990), "A Counterexample in Semimetric Spaces", Extracta Mathematicae 5 (1): 38–40, https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/118277.pdf

- ↑ Schaefer & Wolff 1999, pp. 1–11.

- ↑ Bourbaki 1989, pp. 129–133.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 Wilansky 2008, pp. 32–35.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Dugundji 1966, pp. 219–221.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Jech 2006, pp. 73–89.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Császár 1978, pp. 53–65, 82–91, 102–120.

- ↑ Dolecki & Mynard 2016, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Dolecki & Mynard 2016, pp. 37–39.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Arkhangel'skii & Ponomarev 1984, pp. 20–22.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 39.7 Császár 1978, pp. 102–120.

- ↑ Bourbaki 1989, pp. 68–83.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Dixmier 1984, pp. 13–18.

- ↑ Bourbaki 1989, pp. 69.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 43.4 43.5 43.6 43.7 Bourbaki 1989, pp. 68–74.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Bourbaki 1989, p. 70.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 45.6 45.7 45.8 Bourbaki 1989, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Dixmier 1984, pp. 14–17.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Kelley 1975, pp. 65–72.

- ↑ Bruns G., Schmidt J.,Zur Aquivalenz von Moore-Smith-Folgen und Filtern, Math. Nachr. 13 (1955), 169-186.

- ↑ Dugundji 1966, p. 220–221.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 Dugundji 1966, pp. 211–221.

- ↑ Dugundji 1966, p. 60.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Dugundji 1966, pp. 215–216.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 53.5 53.6 53.7 53.8 Schechter 1996, pp. 157–168.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Clark, Pete L. (18 October 2016). "Convergence". http://math.uga.edu/~pete/convergence.pdf.

- ↑ Bourbaki 1989, p. 129.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Bourbaki 1989, p. 83.

- ↑ Bourbaki 1989, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Dugundji 1966, pp. 216.

- Template:Adams Franzosa Introduction to Topology Pure and Applied

- Template:Arkhangel'skii Ponomarev Fundamentals of General Topology Problems and Exercises

- Jarchow, Hans (1981). Locally convex spaces. Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner. ISBN 978-3-519-02224-4. OCLC 8210342.

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1989). General Topology: Chapters 1–4. Éléments de mathématique. Berlin New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-64241-1. OCLC 18588129. https://doku.pub/documents/31425779-nicolas-bourbaki-general-topology-part-i1pdf-30j71z37920w.

- Template:Bourbaki General Topology Part II Chapters 5-10

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1987). Topological Vector Spaces: Chapters 1–5. Éléments de mathématique. 2. Berlin New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-540-42338-6. OCLC 17499190. http://www.numdam.org/item?id=AIF_1950__2__5_0.

- Burris, Stanley; Sankappanavar, Hanamantagouda P. (2012). A Course in Universal Algebra. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-9880552-0-9. http://www.thoralf.uwaterloo.ca/htdocs/ualg.html.

- Cartan, Henri (1937a). "Théorie des filtres". Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences 205: 595–598. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3157c/f594.image.

- Cartan, Henri (1937b). "Filtres et ultrafiltres". Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences 205: 777–779. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k3157c/f776.image.

- Template:Comfort Negrepontis The Theory of Ultrafilters 1974

- Template:Császár General Topology

- Template:Dixmier General Topology

- Dolecki, Szymon; Mynard, Frederic (2016). Convergence Foundations Of Topology. New Jersey: World Scientific Publishing Company. ISBN 978-981-4571-52-4. OCLC 945169917.

- Dugundji, James (1966). Topology. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. ISBN 978-0-697-06889-7. OCLC 395340485.

- Template:Dunford Schwartz Linear Operators Part 1 General Theory

- Edwards, Robert E. (Jan 1, 1995). Functional Analysis: Theory and Applications. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-68143-6. OCLC 30593138.

- Template:Howes Modern Analysis and Topology 1995

- Jarchow, Hans (1981). Locally convex spaces. Stuttgart: B.G. Teubner. ISBN 978-3-519-02224-4. OCLC 8210342.

- Jech, Thomas (2006). Set Theory: The Third Millennium Edition, Revised and Expanded. Berlin New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-540-44085-7. OCLC 50422939.

- Template:Joshi Introduction to General Topology

- Template:Kelley General Topology

- Köthe, Gottfried (1969). Topological Vector Spaces I. Grundlehren der mathematischen Wissenschaften. 159. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-64988-2. OCLC 840293704.

- MacIver R., David (1 July 2004). "Filters in Analysis and Topology". http://www.efnet-math.org/~david/mathematics/filters.pdf. (Provides an introductory review of filters in topology and in metric spaces.)

- Narici, Lawrence; Beckenstein, Edward (2011). Topological Vector Spaces. Pure and applied mathematics (Second ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1584888666. OCLC 144216834.

- Robertson, Alex P.; Robertson, Wendy J. (1980). Topological Vector Spaces. Cambridge Tracts in Mathematics. 53. Cambridge England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29882-7. OCLC 589250.

- Schaefer, Helmut H.; Wolff, Manfred P. (1999). Topological Vector Spaces. GTM. 8 (Second ed.). New York, NY: Springer New York Imprint Springer. ISBN 978-1-4612-7155-0. OCLC 840278135.

- Schechter, Eric (1996). Handbook of Analysis and Its Foundations. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-622760-4. OCLC 175294365.

- Template:Schubert Topology

- Trèves, François (August 6, 2006). Topological Vector Spaces, Distributions and Kernels. Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-45352-1. OCLC 853623322.

- Wilansky, Albert (2013). Modern Methods in Topological Vector Spaces. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-486-49353-4. OCLC 849801114.

- Template:Wilansky Topology for Analysis 2008

- Willard, Stephen (2004). General Topology. Dover Books on Mathematics (First ed.). Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-43479-7. OCLC 115240.

Contents

Filters in topology

From HandWiki - Reading time: 102 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 102 min

Filters in topology, a subfield of mathematics, can be used to study topological spaces and define all basic topological notions such as convergence, continuity, compactness, and more. Filters, which are special families of subsets of some given set, also provide a common framework for defining various types of limits of functions such as limits from the left/right, to infinity, to a point or a set, and many others. Special types of filters called ultrafilters have many useful technical properties and they may often be used in place of arbitrary filters.

Filters have generalizations called prefilters (also known as filter bases) and filter subbases, all of which appear naturally and repeatedly throughout topology. Examples include neighborhood filters/bases/subbases and uniformities. Every filter is a prefilter and both are filter subbases. Every prefilter and filter subbase is contained in a unique smallest filter, which they are said to generate. This establishes a relationship between filters and prefilters that may often be exploited to allow one to use whichever of these two notions is more technically convenient. There is a certain preorder on families of sets, denoted by that helps to determine exactly when and how one notion (filter, prefilter, etc.) can or cannot be used in place of another. This preorder's importance is amplified by the fact that it also defines the notion of filter convergence, where by definition, a filter (or prefilter) converges to a point if and only if where is that point's neighborhood filter. Consequently, subordination also plays an important role in many concepts that are related to convergence, such as cluster points and limits of functions. In addition, the relation which denotes and is expressed by saying that is subordinate to also establishes a relationship in which is to as a subsequence is to a sequence (that is, the relation which is called subordination, is for filters the analog of "is a subsequence of").

Filters were introduced by Henri Cartan in 1937[1] and subsequently used by Bourbaki in their book Topologie Générale as an alternative to the similar notion of a net developed in 1922 by E. H. Moore and H. L. Smith. Filters can also be used to characterize the notions of sequence and net convergence. But unlike[note 1] sequence and net convergence, filter convergence is defined entirely in terms of subsets of the topological space and so it provides a notion of convergence that is completely intrinsic to the topological space; indeed, the category of topological spaces can be equivalently defined entirely in terms of filters. Every net induces a canonical filter and dually, every filter induces a canonical net, where this induced net (resp. induced filter) converges to a point if and only if the same is true of the original filter (resp. net). This characterization also holds for many other definitions such as cluster points. These relationships make it possible to switch between filters and nets, and they often also allow one to choose whichever of these two notions (filter or net) is more convenient for the problem at hand. However, assuming that "subnet" is defined using either of its most popular definitions (which are those given by Willard and by Kelley), then in general, this relationship does not extend to subordinate filters and subnets because as detailed below, there exist subordinate filters whose filter/subordinate–filter relationship cannot be described in terms of the corresponding net/subnet relationship; this issue can however be resolved by using a less commonly encountered definition of "subnet", which is that of an AA–subnet.

Thus filters/prefilters and this single preorder provide a framework that seamlessly ties together fundamental topological concepts such as topological spaces (via neighborhood filters), neighborhood bases, convergence, various limits of functions, continuity, compactness, sequences (via sequential filters), the filter equivalent of "subsequence" (subordination), uniform spaces, and more; concepts that otherwise seem relatively disparate and whose relationships are less clear.

Contents

Motivation

Archetypical example of a filter

The archetypical example of a filter is the neighborhood filter at a point in a topological space which is the family of sets consisting of all neighborhoods of

By definition, a neighborhood of some given point is any subset whose topological interior contains this point; that is, such that Importantly, neighborhoods are not required to be open sets; those are called open neighborhoods.

Listed below are those fundamental properties of neighborhood filters that ultimately became the definition of a "filter."

A filter on is a set of subsets of that satisfies all of the following conditions:

Generalizing sequence convergence by using sets − determining sequence convergence without the sequence

A sequence in is by definition a map from the natural numbers into the space

The original notion of convergence in a topological space was that of a sequence converging to some given point in a space, such as a metric space.

With metrizable spaces (or more generally first–countable spaces or Fréchet–Urysohn spaces), sequences usually suffices to characterize, or "describe", most topological properties, such as the closures of subsets or continuity of functions.

But there are many spaces where sequences can not be used to describe even basic topological properties like closure or continuity.

This failure of sequences was the motivation for defining notions such as nets and filters, which never fail to characterize topological properties.

Nets directly generalize the notion of a sequence since nets are, by definition, maps from an arbitrary directed set into the space A sequence is just a net whose domain is with the natural ordering. Nets have their own notion of convergence, which is a direct generalization of sequence convergence.

Filters generalize sequence convergence in a different way by considering only the values of a sequence. To see how this is done, consider a sequence which is by definition just a function whose value at is denoted by rather than by the usual parentheses notation that is commonly used for arbitrary functions. Knowing only the image (sometimes called "the range") of the sequence is not enough to characterize its convergence; multiple sets are needed. It turns out that the needed sets are the following,[note 2] which are called the tails of the sequence :

These sets completely determine this sequence's convergence (or non–convergence) because given any point, this sequence converges to it if and only if for every neighborhood (of this point), there is some integer such that contains all of the points This can be reworded as:

Script error: No such module "in5".every neighborhood must contain some set of the form as a subset.

Or more briefly: every neighborhood must contain some tail as a subset. It is this characterization that can be used with the above family of tails to determine convergence (or non–convergence) of the sequence Specifically, with the family of sets in hand, the function is no longer needed to determine convergence of this sequence (no matter what topology is placed on ). By generalizing this observation, the notion of "convergence" can be extended from sequences/functions to families of sets.

The above set of tails of a sequence is in general not a filter but it does "generate" a filter via taking its upward closure (which consists of all supersets of all tails). The same is true of other important families of sets such as any neighborhood basis at a given point, which in general is also not a filter but does generate a filter via its upward closure (in particular, it generates the neighborhood filter at that point). The properties that these families share led to the notion of a filter base, also called a prefilter, which by definition is any family having the minimal properties necessary and sufficient for it to generate a filter via taking its upward closure.

Nets versus filters − advantages and disadvantages

Filters and nets each have their own advantages and drawbacks and there's no reason to use one notion exclusively over the other.[note 3] Depending on what is being proved, a proof may be made significantly easier by using one of these notions instead of the other.[2] Both filters and nets can be used to completely characterize any given topology. Nets are direct generalizations of sequences and can often be used similarly to sequences, so the learning curve for nets is typically much less steep than that for filters. However, filters, and especially ultrafilters, have many more uses outside of topology, such as in set theory, mathematical logic, model theory (ultraproducts, for example), abstract algebra,[3] combinatorics,[4] dynamics,[4] order theory, generalized convergence spaces, Cauchy spaces, and in the definition and use of hyperreal numbers.

Like sequences, nets are functions and so they have the advantages of functions. For example, like sequences, nets can be "plugged into" other functions, where "plugging in" is just function composition. Theorems related to functions and function composition may then be applied to nets. One example is the universal property of inverse limits, which is defined in terms of composition of functions rather than sets and it is more readily applied to functions like nets than to sets like filters (a prominent example of an inverse limit is the Cartesian product). Filters may be awkward to use in certain situations, such as when switching between a filter on a space and a filter on a dense subspace [5]

In contrast to nets, filters (and prefilters) are families of sets and so they have the advantages of sets. For example, if is surjective then the image under of an arbitrary filter or prefilter is both easily defined and guaranteed to be a prefilter on 's domain, whereas it is less clear how to pullback (unambiguously/without choice) an arbitrary sequence (or net) so as to obtain a sequence or net in the domain (unless is also injective and consequently a bijection, which is a stringent requirement). Similarly, the intersection of any collection of filters is once again a filter whereas it is not clear what this could mean for sequences or nets. Because filters are composed of subsets of the very topological space that is under consideration, topological set operations (such as closure or interior) may be applied to the sets that constitute the filter. Taking the closure of all the sets in a filter is sometimes useful in functional analysis for instance. Theorems and results about images or preimages of sets under a function may also be applied to the sets that constitute a filter; an example of such a result might be one of continuity's characterizations in terms of preimages of open/closed sets or in terms of the interior/closure operators. Special types of filters called ultrafilters have many useful properties that can significantly help in proving results. One downside of nets is their dependence on the directed sets that constitute their domains, which in general may be entirely unrelated to the space In fact, the class of nets in a given set is too large to even be a set (it is a proper class); this is because nets in can have domains of any cardinality. In contrast, the collection of all filters (and of all prefilters) on is a set whose cardinality is no larger than that of Similar to a topology on a filter on is "intrinsic to " in the sense that both structures consist entirely of subsets of and neither definition requires any set that cannot be constructed from (such as or other directed sets, which sequences and nets require).

Preliminaries, notation, and basic notions

In this article, upper case Roman letters like denote sets (but not families unless indicated otherwise) and will denote the power set of A subset of a power set is called a family of sets (or simply, a family) where it is over if it is a subset of Families of sets will be denoted by upper case calligraphy letters such as Whenever these assumptions are needed, then it should be assumed that is non–empty and that etc. are families of sets over

The terms "prefilter" and "filter base" are synonyms and will be used interchangeably.

Warning about competing definitions and notation

There are unfortunately several terms in the theory of filters that are defined differently by different authors. These include some of the most important terms such as "filter." While different definitions of the same term usually have significant overlap, due to the very technical nature of filters (and point–set topology), these differences in definitions nevertheless often have important consequences. When reading mathematical literature, it is recommended that readers check how the terminology related to filters is defined by the author. For this reason, this article will clearly state all definitions as they are used. Unfortunately, not all notation related to filters is well established and some notation varies greatly across the literature (for example, the notation for the set of all prefilters on a set) so in such cases this article uses whatever notation is most self describing or easily remembered.

The theory of filters and prefilters is well developed and has a plethora of definitions and notations, many of which are now unceremoniously listed to prevent this article from becoming prolix and to allow for the easy look up of notation and definitions. Their important properties are described later.

Sets operations

The upward closure or isotonization in [6][7] of a family of sets is

and similarly the downward closure of is

| Notation and Definition | Name |

|---|---|

| Kernel of [7] | |

| Dual of where is a set.[8] | |

| Trace of [8] or the restriction of where is a set; sometimes denoted by | |

| [9] | Elementwise (set) intersection ( will denote the usual intersection) |

| [9] | Elementwise (set) union ( will denote the usual union) |

| Elementwise (set) subtraction ( will denote the usual set subtraction) | |

| Power set of a set [7] |

If and then are said to be equivalent (with respect to subordination).

Two families mesh,[8] written ifThroughout, is a map.

| Notation and Definition | Name |

|---|---|

| [13] | Image of or the preimage of under |

| [14] | Image of under |

| Image (or range) of |

Topology notation

Denote the set of all topologies on a set Suppose is any subset, and is any point.

| Notation and Definition | Name |

|---|---|

| Set or prefilter[note 4] of open neighborhoods of | |

| Set or prefilter of open neighborhoods of | |

| Set or filter[note 4] of neighborhoods of | |

| Set or filter of neighborhoods of |

If then

Nets and their tails

A directed set is a set together with a preorder, which will be denoted by (unless explicitly indicated otherwise), that makes into an (upward) directed set;[15] this means that for all there exists some such that For any indices the notation is defined to mean while is defined to mean that holds but it is not true that (if is antisymmetric then this is equivalent to ).

A net in [15] is a map from a non–empty directed set into The notation will be used to denote a net with domain

| Notation and Definition | Name |

|---|---|

| Tail or section of starting at where is a directed set. | |

| Tail or section of starting at | |

| Set or prefilter of tails/sections of Also called the eventuality filter base generated by (the tails of) If is a sequence then is also called the sequential filter base.[16] | |

| (Eventuality) filter of/generated by (tails of) [16] | |

| Tail or section of a net starting at [16] where is a directed set. |

Warning about using strict comparison

If is a net and then it is possible for the set which is called the tail of after , to be empty (for example, this happens if is an upper bound of the directed set ). In this case, the family would contain the empty set, which would prevent it from being a prefilter (defined later). This is the (important) reason for defining as rather than or even and it is for this reason that in general, when dealing with the prefilter of tails of a net, the strict inequality may not be used interchangeably with the inequality

Filters and prefilters

The following is a list of properties that a family of sets may possess and they form the defining properties of filters, prefilters, and filter subbases. Whenever it is necessary, it should be assumed that

The family of sets is:

Many of the properties of defined above and below, such as "proper" and "directed downward," do not depend on so mentioning the set is optional when using such terms. Definitions involving being "upward closed in " such as that of "filter on " do depend on so the set should be mentioned if it is not clear from context.

A family is/is a(n):

There are no prefilters on (nor are there any nets valued in ), which is why this article, like most authors, will automatically assume without comment that whenever this assumption is needed.

Basic examples

Named examples

Other examples

Ultrafilters

There are many other characterizations of "ultrafilter" and "ultra prefilter," which are listed in the article on ultrafilters. Important properties of ultrafilters are also described in that article.

A non–empty family of sets is/is an:

The ultrafilter lemma

The following important theorem is due to Alfred Tarski (1930).[34]

The ultrafilter lemma/principle/theorem[28] (Tarski) — Every filter on a set is a subset of some ultrafilter on

A consequence of the ultrafilter lemma is that every filter is equal to the intersection of all ultrafilters containing it.[28] Assuming the axioms of Zermelo–Fraenkel (ZF), the ultrafilter lemma follows from the Axiom of choice (in particular from Zorn's lemma) but is strictly weaker than it. The ultrafilter lemma implies the Axiom of choice for finite sets. If only dealing with Hausdorff spaces, then most basic results (as encountered in introductory courses) in Topology (such as Tychonoff's theorem for compact Hausdorff spaces and the Alexander subbase theorem) and in functional analysis (such as the Hahn–Banach theorem) can be proven using only the ultrafilter lemma; the full strength of the axiom of choice might not be needed.

Kernels

The kernel is useful in classifying properties of prefilters and other families of sets.

The kernel[6] of a family of sets is the intersection of all sets that are elements of

If then and this set is also equal to the kernel of the π–system that is generated by In particular, if is a filter subbase then the kernels of all of the following sets are equal:

If is a map then Equivalent families have equal kernels. Two principal families are equivalent if and only if their kernels are equal.

Classifying families by their kernels

A family of sets is:

If is a principal filter on then and and is also the smallest prefilter that generates

Family of examples: For any non–empty the family is free but it is a filter subbase if and only if no finite union of the form covers in which case the filter that it generates will also be free. In particular, is a filter subbase if is countable (for example, the primes), a meager set in a set of finite measure, or a bounded subset of If is a singleton set then is a subbase for the Fréchet filter on

Characterizing fixed ultra prefilters

If a family of sets is fixed (that is, ) then is ultra if and only if some element of is a singleton set, in which case will necessarily be a prefilter. Every principal prefilter is fixed, so a principal prefilter is ultra if and only if is a singleton set.

Every filter on that is principal at a single point is an ultrafilter, and if in addition is finite, then there are no ultrafilters on other than these.[7]

The next theorem shows that every ultrafilter falls into one of two categories: either it is free or else it is a principal filter generated by a single point.

Proposition — If is an ultrafilter on then the following are equivalent:

Finer/coarser, subordination, and meshing

The preorder that is defined below is of fundamental importance for the use of prefilters (and filters) in topology. For instance, this preorder is used to define the prefilter equivalent of "subsequence",[26] where "" can be interpreted as " is a subsequence of " (so "subordinate to" is the prefilter equivalent of "subsequence of"). It is also used to define prefilter convergence in a topological space. The definition of meshes with which is closely related to the preorder is used in topology to define cluster points.

Two families of sets mesh[8] and are compatible, indicated by writing if If do not mesh then they are dissociated. If then are said to mesh if mesh, or equivalently, if the trace of which is the family does not contain the empty set, where the trace is also called the restriction of

Declare that stated as is coarser than and is finer than (or subordinate to) [28][11][12][9][20] if any of the following equivalent conditions hold:

and if in addition is upward closed, which means that then this list can be extended to include:

If an upward closed family is finer than (that is, ) but then is said to be strictly finer than and is strictly coarser than Two families are comparable if one of them is finer than the other.[28]

Example: If is a subsequence of then is subordinate to in symbols: and also Stated in plain English, the prefilter of tails of a subsequence is always subordinate to that of the original sequence. To see this, let be arbitrary (or equivalently, let be arbitrary) and it remains to show that this set contains some For the set to contain it is sufficient to have Since are strictly increasing integers, there exists such that and so holds, as desired. Consequently, The left hand side will be a strict/proper subset of the right hand side if (for instance) every point of is unique (that is, when is injective) and is the even-indexed subsequence because under these conditions, every tail (for every ) of the subsequence will belong to the right hand side filter but not to the left hand side filter.

For another example, if is any family then always holds and furthermore,

A non-empty family that is coarser than a filter subbase must itself be a filter subbase.[9] Every filter subbase is coarser than both the π–system that it generates and the filter that it generates.[9]

If are families such that the family is ultra, and then is necessarily ultra. It follows that any family that is equivalent to an ultra family will necessarily be ultra. In particular, if is a prefilter then either both and the filter it generates are ultra or neither one is ultra.

The relation is reflexive and transitive, which makes it into a preorder on [35] The relation is antisymmetric but if has more than one point then it is not symmetric.

Equivalent families of sets

The preorder induces its canonical equivalence relation on where for all is equivalent to if any of the following equivalent conditions hold:[9][6]

Two upward closed (in ) subsets of are equivalent if and only if they are equal.[9] If then necessarily and is equivalent to Every equivalence class other than contains a unique representative (that is, element of the equivalence class) that is upward closed in [9]

Properties preserved between equivalent families

Let be arbitrary and let be any family of sets. If are equivalent (which implies that ) then for each of the statements/properties listed below, either it is true of both or else it is false of both :[35]

Missing from the above list is the word "filter" because this property is not preserved by equivalence. However, if are filters on then they are equivalent if and only if they are equal; this characterization does not extend to prefilters.

Equivalence of prefilters and filter subbases

If is a prefilter on then the following families are always equivalent to each other:

and moreover, these three families all generate the same filter on (that is, the upward closures in of these families are equal).

In particular, every prefilter is equivalent to the filter that it generates. By transitivity, two prefilters are equivalent if and only if they generate the same filter.[9] Every prefilter is equivalent to exactly one filter on which is the filter that it generates (that is, the prefilter's upward closure). Said differently, every equivalence class of prefilters contains exactly one representative that is a filter. In this way, filters can be considered as just being distinguished elements of these equivalence classes of prefilters.[9]

A filter subbase that is not also a prefilter cannot be equivalent to the prefilter (or filter) that it generates. In contrast, every prefilter is equivalent to the filter that it generates. This is why prefilters can, by and large, be used interchangeably with the filters that they generate while filter subbases cannot.

Set theoretic properties and constructions relevant to topology

Trace and meshing

If is a prefilter (resp. filter) on then the trace of which is the family is a prefilter (resp. a filter) if and only if mesh (that is, [28]), in which case the trace of is said to be induced by . The trace is always finer than the original family; that is, If is ultra and if mesh then the trace is ultra. If is an ultrafilter on then the trace of is a filter on if and only if

For example, suppose that is a filter on is such that Then mesh and generates a filter on that is strictly finer than [28]

When prefilters mesh

Given non–empty families the family satisfies and If is proper (resp. a prefilter, a filter subbase) then this is also true of both In order to make any meaningful deductions about from needs to be proper (that is, which is the motivation for the definition of "mesh". In this case, is a prefilter (resp. filter subbase) if and only if this is true of both Said differently, if are prefilters then they mesh if and only if is a prefilter. Generalizing gives a well known characterization of "mesh" entirely in terms of subordination (that is, ):

Script error: No such module "in5".Two prefilters (resp. filter subbases) mesh if and only if there exists a prefilter (resp. filter subbase) such that and

If the least upper bound of two filters exists in then this least upper bound is equal to [36]

Images and preimages under functions

Throughout, will be maps between non–empty sets.

Images of prefilters

Let Many of the properties that may have are preserved under images of maps; notable exceptions include being upward closed, being closed under finite intersections, and being a filter, which are not necessarily preserved.

Explicitly, if one of the following properties is true of then it will necessarily also be true of (although possibly not on the codomain unless is surjective):[28][13][37][38][39][34] ultra, ultrafilter, filter, prefilter, filter subbase, dual ideal, upward closed, proper/non–degenerate, ideal, closed under finite unions, downward closed, directed upward. Moreover, if is a prefilter then so are both [28] The image under a map of an ultra set is again ultra and if is an ultra prefilter then so is

If is a filter then is a filter on the range but it is a filter on the codomain if and only if is surjective.[37] Otherwise it is just a prefilter on and its upward closure must be taken in to obtain a filter. The upward closure of is where if is upward closed in (that is, a filter) then this simplifies to:

If then taking to be the inclusion map shows that any prefilter (resp. ultra prefilter, filter subbase) on is also a prefilter (resp. ultra prefilter, filter subbase) on [28]

Preimages of prefilters

Let Under the assumption that is surjective:

Script error: No such module "in5". is a prefilter (resp. filter subbase, π–system, closed under finite unions, proper) if and only if this is true of

However, if is an ultrafilter on then even if is surjective (which would make a prefilter), it is nevertheless still possible for the prefilter to be neither ultra nor a filter on [38]

If is not surjective then denote the trace of by where in this case particular case the trace satisfies: and consequently also:

This last equality and the fact that the trace is a family of sets over means that to draw conclusions about the trace can be used in place of and the surjection can be used in place of For example:[13][28][39]

Script error: No such module "in5". is a prefilter (resp. filter subbase, π–system, proper) if and only if this is true of

In this way, the case where is not (necessarily) surjective can be reduced down to the case of a surjective function (which is a case that was described at the start of this subsection).

Even if is an ultrafilter on if is not surjective then it is nevertheless possible that which would make degenerate as well. The next characterization shows that degeneracy is the only obstacle. If is a prefilter then the following are equivalent:[13][28][39]

and moreover, if is a prefilter then so is [13][28]

If and if denotes the inclusion map then the trace of is equal to [28] This observation allows the results in this subsection to be applied to investigating the trace on a set.

Subordination is preserved by images and preimages

The relation is preserved under both images and preimages of families of sets.[28] This means that for any families [39]

Moreover, the following relations always hold for any family of sets :[39] where equality will hold if is surjective.[39] Furthermore,

If then[20] and [39] where equality will hold if is injective.[39]

Products of prefilters

Suppose is a family of one or more non–empty sets, whose product will be denoted by and for every index let denote the canonical projection. Let be non−empty families, also indexed by such that for each The product of the families [28] is defined identically to how the basic open subsets of the product topology are defined (had all of these been topologies). That is, both the notations denote the family of all cylinder subsets such that for all but finitely many and where for any one of these finitely many exceptions (that is, for any such that necessarily ). When every is a filter subbase then the family is a filter subbase for the filter on generated by [28] If is a filter subbase then the filter on that it generates is called the filter generated by .[28] If every is a prefilter on then will be a prefilter on and moreover, this prefilter is equal to the coarsest prefilter such that for every [28] However, may fail to be a filter on even if every is a filter on [28]

Convergence, limits, and cluster points

Throughout, is a topological space.

Prefilters vs. filters

With respect to maps and subsets, the property of being a prefilter is in general more well behaved and better preserved than the property of being a filter. For instance, the image of a prefilter under some map is again a prefilter; but the image of a filter under a non–surjective map is never a filter on the codomain, although it will be a prefilter. The situation is the same with preimages under non–injective maps (even if the map is surjective). If is a proper subset then any filter on will not be a filter on although it will be a prefilter.

One advantage that filters have is that they are distinguished representatives of their equivalence class (relative to ), meaning that any equivalence class of prefilters contains a unique filter. This property may be useful when dealing with equivalence classes of prefilters (for instance, they are useful in the construction of completions of uniform spaces via Cauchy filters). The many properties that characterize ultrafilters are also often useful. They are used to, for example, construct the Stone–Čech compactification. The use of ultrafilters generally requires that the ultrafilter lemma be assumed. But in the many fields where the axiom of choice (or the Hahn–Banach theorem) is assumed, the ultrafilter lemma necessarily holds and does not require an addition assumption.

A note on intuition

Suppose that is a non–principal filter on an infinite set has one "upward" property (that of being closed upward) and one "downward" property (that of being directed downward). Starting with any there always exists some that is a proper subset of ; this may be continued ad infinitum to get a sequence of sets in with each being a proper subset of The same is not true going "upward", for if then there is no set in that contains as a proper subset. Thus when it comes to limiting behavior (which is a topic central to the field of topology), going "upward" leads to a dead end, while going "downward" is typically fruitful. So to gain understanding and intuition about how filters (and prefilter) relate to concepts in topology, the "downward" property is usually the one to concentrate on. This is also why so many topological properties can be described by using only prefilters, rather than requiring filters (which only differ from prefilters in that they are also upward closed). The "upward" property of filters is less important for topological intuition but it is sometimes useful to have for technical reasons. For example, with respect to every filter subbase is contained in a unique smallest filter but there may not exist a unique smallest prefilter containing it.

Limits and convergence

Script error: No such module "in5".A family is said to converge in to a point or subset of [8] if Explicitly, means that every neighborhood contains some as a subset (that is, ); thus the following then holds: In words, a family converges to a point or subset if and only if it is finer than the neighborhood filter at A family converging to a point or subset may be indicated by writing [32] and saying that is a limit of if this limit is a point (and not a subset), then is also called a limit point.[40] As usual, is defined to mean that and is the only limit point of that is, if also [32] (If the notation "" did not also require that the limit point be unique then the equals sign = would no longer be guaranteed to be transitive). The set of all limit points of is denoted by [8]

In the above definitions, it suffices to check that is finer than some (or equivalently, finer than every) neighborhood base in of the point or set (for example, such as or when ).

Examples

If is Euclidean space and denotes the Euclidean norm (which is the distance from the origin, defined as usual), then all of the following families converge to the origin:

Although was assumed to be the Euclidean norm, the example above remains valid for any other norm on

The one and only limit point in of the free prefilter is since every open ball around the origin contains some open interval of this form. The fixed prefilter does not converges in to any point and so although does converge to the set since However, not every fixed prefilter converges to its kernel. For instance, the fixed prefilter also has kernel but does not converges (in ) to it.

The free prefilter of intervals does not converge (in ) to any point, and it converges to a subset if and only if (that is, if and only if the set contains some interval of the form as a subset). The same is also true of the prefilter because it is equivalent to and equivalent families have the same limits. In fact, if is any prefilter in any topological space then for every in particular, every prefilter converges to the set More generally, because the only neighborhood of is itself (that is, ), every non-empty family (including every filter subbase) converges to

For any point or subset its neighborhood filter always converges to More generally, any neighborhood basis at converges to In any topological space, a family converges to a point if and only if it converges to the singleton set When a space carries the indiscrete topology then every non-empty family converges to every non-empty subset (and thus also to every point since singleton sets are non-empty). A point is always a limit point of the principle ultra prefilter and of the ultrafilter that it generates. The empty family does not converge to any point nor to any set. Because the empty set is always an open neighborhood of itself, a family converges to if and only if Thus no filter, prefilter, or other non-degenerate family can converge to the empty set.

If is a non-empty subset then and consequently, if for all then Applying this to this says that if a family has at least one limit point, then it converges to its set of limit points:

Basic properties