Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement

Topic: Finance

From HandWiki - Reading time: 19 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 19 min

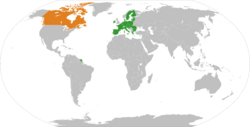

Canada (orange) and the European Union (green) | |

| Type | Trade agreement |

|---|---|

| Signed | 30 October 2016 |

| Location | Brussels |

| Effective | Not in force (parts are provisionally applied) |

| Condition | Approval by all signatories |

| Provisional application | 21 September 2017[1] |

| Signatories |

|

| Ratifiers | 14 EU members[2] |

| Languages | |

The Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) (unofficially, Canada-Europe Trade Agreement) is a free-trade agreement between Canada and the European Union.[3][4][5] It has been provisionally applied,[6] thus removing 98% of the preexisting tariffs between the two parts.

The negotiations were concluded in August 2014. All 28 European Union member states approved the final text of CETA for signature, with Belgium being the final country to give its approval.[7] Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada, travelled to Brussels on 30 October 2016 to sign on behalf of Canada.[8] The European Parliament approved the deal on 15 February 2017.[9] The agreement is subject to ratification by the EU and national legislatures.[5][10] It could only enter into force if no adverse opinion on the dispute resolution mechanism was given by the European Court of Justice following a request for an opinion by Belgium.[11] The European Court of Justice has stated in its opinion that the dispute resolution mechanism complies with EU law.[12] Until its formal entry into force, substantial parts are provisionally applied from 21 September 2017.[1]

The European Commission indicates the treaty will lead to savings of just over half a billion euros in taxes for EU exporters every year, mutual recognition in regulated professions such as architects, accountants and engineers, and easier transfers of company staff and other professionals between the EU and Canada. The European Commission claims CETA will create a more level playing field between Canada and the EU on intellectual property rights.[13]

Proponents of CETA emphasize that the agreement will boost trade between the EU and Canada and thus create new jobs, facilitate business operations by abolishing customs duties, goods checks, and various other levies, facilitate mutual recognition of diplomas and regulate investment disputes by creating a new system of courts.[14][15] Opponents consider that CETA would weaken European consumer rights, including high EU standards concerning food safety,[16] and criticize it as a boon only for big business and multinational corporations, while risking net-losses, unemployment, and environmental damage impacting individual citizens.[17][18][19] The deal also includes a controversial investor-state dispute settlement mechanism which makes critics fear that multinational corporations could sue national governments for billions of dollars if they thought that the government policies had a bad impact on their business.[15] A poll conducted by Angus Reid Institute in February 2017 concluded that 55 percent of Canadians support CETA, while only 10 percent oppose it. The support, however, has waned when compared to the poll conducted in 2014.[20] In contrast, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) has a 44 percent support rate among Canadians in February 2017.[21] In contrast to Canada, the agreement has prompted protests in a number of European countries.

History

CETA is Canada's biggest bilateral initiative since NAFTA. It was started as a result of a joint study "Assessing the Costs and Benefits of a Closer EU-Canada Economic Partnership",[22] which was released in October 2008. Officials announced the launch of negotiations on 6 May 2009 at the Canada-EU Summit in Prague.[4][23] This, after the Canada-EU Summit in Ottawa on 18 March 2004 where leaders agreed to a framework for a new Canada-EU Trade and Investment Enhancement Agreement (TIEA). The TIEA was intended to move beyond traditional market access issues, to include areas such as trade and investment facilitation, competition, mutual recognition of professional qualifications, financial services, e-commerce, temporary entry, small- and medium-sized enterprises, sustainable development, and sharing science and technology. The TIEA was also to build on a Canada-EU regulatory co-operation framework for promoting bilateral co-operation on approaches to regulatory governance, advancing good regulatory practices and facilitating trade and investment. In addition to lowering barriers, the TIEA was meant to heighten Canadian and European interest in each other's markets.[24] The TIEA continued until 2006 when Canada and the EU decided to pause negotiations. This led to negotiations for a Canada-European Union trade agreement (later renamed as the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement, or CETA), and this agreement will go beyond the TIEA toward an agreement with a much broader and more ambitious scope.

An agreement in principle was signed by Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper and European Commission President José Manuel Barroso on 18 October 2013. The negotiations were concluded on 1 August 2014.[25] The trade agreement was officially presented on 25 September 2014 by Harper and Barroso during an EU - Canada Summit at the Royal York Hotel in downtown Toronto.[26] The Canada Europe Roundtable for Business has served as the parallel business process from the launch to the conclusion of the CETA negotiations.

After it had been leaked by German public television on 14 August, the 1634 pages long Consolidated CETA text was published on the EU's official website on 26 September 2014.[27]

Completion, translation of the final text into 24 EU languages, and ratification is expected to take years since the passage of the deal requires approval of the European Parliament and the European Council as well as Canada and the individual 28 EU member states as well.[28][29]

Research commissioned by negotiating parties

The EU-Canada Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA), a three-part study commissioned by the European Commission to independent experts and completed in September 2011, provided a comprehensive prediction on the impacts of CETA.[30][31][32] It predicts a number of macro-economic and sector-specific impacts, suggesting the EU may see increases in real GDP of 0.02–0.03% in the long-term from CETA, whereas Canada may see increases of 0.18–0.36%; the Investment section of the report suggests these numbers could be higher when factoring in investment increases. At the sectoral level, the study predicts the greatest gains in output and trade to be stimulated by services liberalization and by the removal of tariffs applied on sensitive agricultural products; it also suggests CETA could have a positive social impact if it includes provisions on the ILO's Core Labour Standards and Decent Work Agenda. The study details a variety of impacts in various "cross-cutting" components of CETA: it advocates against controversial NAFTA-style ISDS provisions; predicts potentially imbalanced benefits from a government procurement (GP) chapter; assumes CETA will lead to an upward harmonization in IPR regulations, particularly changing Canadian IPR laws; and predicts impacts in terms of competition policy and several other areas.[32]

Economic ties between the EU and Canada

Canada and the EU have a long history of economic co-operation. Comprising 28 Member States with a total population of over 500 million and a GDP of €13.0 trillion in 2012,[33] the European Union (EU) is the world's second largest single market, foreign investor and trader. As an integrated bloc, the EU represents Canada's second largest trading partner in goods and services. In 2008, Canadian goods and services exports to the EU totalled C$52.2 billion, an increase of 3.9% from 2007, and imports from the EU amounted to $62.4 billion.

According to Statistics Canada, the EU is also the second largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI) in Canada, with the stock of FDI amounting to $133.1 billion at the end of 2008. In 2008, the stock of Canada's direct investment in the EU totalled $136.6 billion, and the EU is the destination of 21.4% of Canadian direct investment abroad. According to Eurostat, the EU identified Canada as its third largest destination and its fourth largest source of FDI in 2007.

Copyright provisions

The neutrality of this article is disputed. (November 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Many of its provisions on copyright were initially thought to be identical to the controversial ACTA, which was rejected by the European Parliament in 2012. The European Commission has indicated[34] that this is not the case.

Part of the Agreement is stricter enforcement of intellectual property, including liability for Internet Service Providers, a ban on technologies that can be used to circumvent copyright.[35] After failure of ACTA the copyright language in CETA was substantially watered down.[36] The following provisions remain:

- WIPO ratification. The EU asked that Canada respect the rights and obligations under the WIPO Internet treaties. The EU only formally ratified those treaties in the week of 16 December 2009.

- Anti-circumvention provisions. The EU asked that Canada implement anti-circumvention provisions that include a ban on the distribution of circumvention devices. There is no such requirement in the WIPO Internet treaties.

- ISP Liability provisions. The treaty requires both EU and Canada to enact safe harbor statutory provisions that would limit ISPs liability where they act as mere conduits, cache content, or host content. These protections may not be conditioned on service providers monitoring their service for possible infringements.

- Enforcement provisions. The EU asked that Canada establish new enforcement provisions including measures to preserve evidence, ordering alleged infringers to disclose information on a wide range of issue[s], mandate disclosure of banking information in commercial infringement cases, allow for injunctive relief, and destruction of goods. There is also a full section on new border measures requirements.

- Making available or distribution rights. The EU asked that Canada implement a distribution or making available right to copyright owners.

These are just the copyright provisions. There are sections dealing with patents, trademarks, designs, and (coming soon) geographical indications. These include:

- requiring Canada to comply with the Trademark Law Treaty (Canada is not a contracting party)

- requiring Canada to accede to the Hague System for the International Registration of Industrial Designs

- creating new legal protections for registered industrial designs including extending the term of protection from the current 10 years to up to 25 years

- requiring Canada to comply with the Patent Law Treaty (Canada has signed but not implemented)

- requiring Canada to establish enhanced protection for data submitted for pharmaceutical patents.

—Dr Michael Geist, Canada Research Chair in Internet and E-commerce Law, University of Ottawa[37]

On 22 October 2012, five Polish NGOs criticized the secrecy surrounding the negotiations, the similarities to ACTA, and demanded more disclosures about the negotiations from the Polish government.[38]

In the Consolidated CETA Text a long section on "Intellectual Property Rights", IPR, (pp. 339–375) deals comprehensively with copyrights, trademarks, patents, designs, trade secrets and licensing. Here reference is made to the TRIPS agreement (p. 339 f). In addition to the interests of the pharmaceutical and software industries CETA encourages to prosecute "Camcording" (the so-called "film piracy", Art. 5.6, p. 343). Especially the negotiations on food exports lasted very long. The interests connected with European cheese exports and Canadian beef exports led to a protection of these kinds of intellectual properties and long lists of "Geographical Indications Identifying a Product Originating in the European Union" (pp. 363–347).[39]

Non-tariff barriers

Agricultural

CETA does not necessarily alter EU non-tariff barriers such as European regulations on beef, which include a ban on the use of growth hormones, but it could do so. Given the cooperation mechanisms institutionalized through the Agreement,[40][41] this cannot be ruled out. Canadian stakeholders have criticized the EU's delays in the approval process for genetically modified organisms (GMOs), and GMO traceability and labelling requirements, none of which are addressed in CETA.[42]

Environmental

Both the EU and Canada will retain the right to regulate freely in areas of public interest such as environmental protection, or people's health and safety.[43]

Impact on fisheries

The provincial Government of Newfoundland and Labrador has argued that the Federal Government of Canada in Ottawa reneged on a deal to pay $280 million in exchange for its relinquishment of minimum processing requirements as part of CETA. Those rules helped protect jobs in fish plants, especially in rural areas hit hard by the cod moratorium, which was instituted in 1992.[44]

Visa disputes

The Czech Republic, Romania and Bulgaria had declared they would not endorse the agreement, in effect scuppering the entire agreement, until the visa requirements for their citizens entering Canada were lifted.[45] All other EU countries already had visa free travel to Canada. Visas requirements were lifted for the Czech Republic on 14 November 2013.[46][47][48] Canada has given a written undertaking to cancel visa requirements for Bulgarian and Romanian nationals visiting Canada for business and tourism, within a timeframe no later than the end of 2017.[49][50] Canada lifted visa requirements for Bulgarian and Romanian citizens on 1 December 2017.[51][52]

Investment protection and investor-state-tribunals

Section 4 of CETA (pages 158–161) provides Investment Protection to foreign investors, and guarantees a "fair and equitable treatment and full protection and security".

CETA allows foreign corporations to sue states before arbitral tribunals if they claim to have suffered losses because a state had violated its Non Discriminatory Treatment obligations (CETA, section 3, p 156 f) or because of a violation of the guaranteed investment protection.

This license exists only in one direction—states cannot sue companies in these investor-state arbitrations. Such investors complaints are nothing new under public international law (UNCTAD listed 514 such cases at the end of 2012, most from the United States, the Netherlands, Great Britain and Germany) but for transatlantic trade and investment, this comprehensive level of parallel justice is new.

After much criticism of the hitherto often confidential arbitral proceedings, CETA now provides for a certain amount of transparency by declaring the UNCITRAL Rules on Transparency in Treaty-based Investor-State Arbitration applicable to all proceedings (article X.33: Transparency of proceedings, p. 174).

While there is no appeal mechanism against arbitration awards comparable to scrutiny of court judgments, awards made under CETA are subject to ICSID (International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes) annulment proceedings if the claim is brought under the ICSID Rules, or setting-aside proceedings if the claim is brought under the UNCITRAL Rules or any other rules the parties have agreed on. Only after time limits set for these review mechanisms have lapsed, is the tribunal's final award to "be binding between the disputing parties and in respect of that particular case". (article X.39: Enforcement of awards, p. 177)

On 26 March 2014, German Economics Minister Sigmar Gabriel wrote an open letter to EU Trade Commissioner Karel De Gucht, stating that investment protection was central sensitive point, which could in the end decide whether a transatlantic free trade agreement would meet with German approval. He further stated that investment arbitration was unnecessary between countries with well-developed legal systems.

The CETA "Investor-State Dispute Settlement" (ISDS) provisions could create a precedent for similar arrangements within TTIP. Furthermore, critics allege that CETA would allow US companies to sue EU states through Canadian subsidiaries.[53][54][55]

In 2016, the EU Commission announced that it had agreed with the Canadian government to replace ad hoc arbitral tribunals in CETA with a permanent dispute settlement tribunal. The tribunal will consist of 15 members named by Canada and the EU, dealing with individual cases in panels of three. An appeals mechanism will be established to ensure "legal correctness" of awards. The tribunal's members may not appear as experts or party counsel in other investment cases.[56]

Signature and ratification

It was initially unclear whether or not the EU member states had to ratify the agreement, as the European Commission considered the treaty to be solely in the competence of the EU.[57] However, in July 2016 it was decided that CETA be qualified as a "mixed agreement" and thus be ratified through national procedures as well.[58]

Shortly before the scheduled signature of CETA on 27 October 2016, Belgium announced it was unable to sign the treaty, as assent is required by all regional governments. The federal government and Flanders, which are governed by the centre-right Michel and Bourgeois governments respectively, are in favour, whereas the French Community, Wallonia and Brussels, which are led by centre-left parties that are in opposition at federal level, rejected signature in its current form. On 27 April 2016, the Walloon Parliament had already adopted a resolution in opposition to CETA. On 13 October 2016, David Lametti defended CETA before a Walloon Parliament committee.[59] However, the next day the Walloon Parliament affirmed its opposition. Walloon Minister-President Paul Magnette led the intra-Belgian opposition shortly before the planned signature.

The intra-Belgian disagreement was solved in the final days of October, paving the way for CETA's signature. On 28 October, the Belgian regional parliaments allowed Full Powers to be given to the federal government, and the following day Minister of Foreign Affairs Didier Reynders gave his signature on behalf of Belgium.[60][61] The next day, on Sunday 30 October 2016, the treaty was signed by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, President of the European Council Donald Tusk, President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker and Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico (as Slovakia held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the second half of 2016).[62]

Following the signature, the consent by the European Parliament and the ratification by Canada, CETA applies provisionally since 21 September 2017,[63] awaiting its ratification by the European Union member states, the European Union and Canada. The procedure is completed when the instrument of ratification is deposited and in many countries requires parliamentary approval.

Parliamentary approval

- The European Parliament approved the agreement on 15 February 2017;[9]

- The Latvian parliament, the Saeima, ratified the agreement on 23 February 2017.

- The Canadian Parliament's bill on CETA, Bill C-30, received Royal Assent on 16 May 2017.[64] The Canadian government had indicated that the agreement would be ratified on or before 1 July 2017,[65] however dispute with the EU regarding details of implementation has delayed the ratification date.[66] After rounds of extensive discussions, the two sides announced that CETA will be provisionally applied on 21 September 2017, nearly three months later than the anticipated date of implementation.[67]

- The Danish parliament, the Folketing, ratified the agreement on 1 June 2017.[68]

- The Spanish parliament, the Cortes Generales, ratified the agreement on 29 June 2017.[69]

- The Croatian parliament, the Sabor, ratified the agreement on 30 June 2017.[70]

- The Czech parliament's upper house, the Senate of the Czech Republic, ratified the agreement on 20 April 2017 and the Czech parliament's lower house, the Chamber of Deputies, ratified the agreement on 13 September 2017.[71][72]

- The Portuguese parliament, the Assembleia da República, ratified the agreement on 20 September 2017.[73]

- The Lithuanian parliament, the Seimas, ratified the agreement on 24 April 2018.[74]

- The French parliament's lower house, the National Assembly, ratified the agreement on 23 July 2019.[75][76] But the upper house, the Senate, has not ratified the agreement yet.

- The Slovak parliament ratified the agreement in September 2019.[77]

- The Luxembourg parliament ratified the agreement in May 2020.[78]

Instruments of ratification

Fifteen states have deposited their instruments of ratification: Austria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, and the UK.[2]

Legal challenge

In Germany, a constitutional complaint made by more than 125,000 people had the Federal Constitutional Court (13 October 2016) examine whether its provisional applicability was compatible with the German Basic Law.[79] The Federal Constitutional Court confirmed this in principle; however, the federal government must ensure

- that a Council decision on the provisional application will only include those areas of CETA that are undisputedly within the competence of the European Union,

- that until a decision by the Federal Constitutional Court is made, the main thing is that the decisions taken in the CETA Joint Committee will be adequately democratically linked, and that

- the interpretation of Art. 30.7 para. 3 letter c CETA enables a unilateral termination of the provisional application by Germany.[80]

A ratification vote by the Bundestag and Bundesrat will not take place before the Federal Constitutional Court judgment as taken place.[81] In January 2020, it was not known when this decision will be made.

In September 2017, Belgium requested the opinion of the European Court of Justice on whether the dispute resolution system of CETA is compatible with EU law. The agreement could not come into force until the ECJ had given its opinion nor if the ECJ opinion were to be that CETA is incompatible with EU law.[11] On 30 April 2019, the European Court of Justice gave its opinion that the system for the resolution of disputes between investors and states in CETA is compatible with EU law.[12]

See also

- Canada–European Free Trade Association Free Trade Agreement

- European Union free trade agreements

- Free-trade agreements of Canada

- Free-trade area

- Rules of Origin

- Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "EU and Canada agree to set a date for the provisional application of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement. Statement by Mr. Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission and. Mr Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada". European Commission. 8 July 2017. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_STATEMENT-17-1959_en.htm. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Agreement Details". Council of the EU. http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/documents-publications/agreements-conventions/agreement/?aid=2016017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ↑ European Commission, EU–Canada, http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/international/cooperating-governments/canada/, retrieved 20 December 2009, "Launched at the May 2009 EU–Canada Summit in Prague, the CETA aims to eliminate trade and investment barriers between the two territories. The CETA has established a historic precedent by including the Canadian provinces directly in the negotiations."

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (Canada), Canada-European Union: Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) Negotiations, http://www.international.gc.ca/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/eu-ue/can-eu-report-intro-can-ue-rapport-intro.aspx, retrieved 20 December 2009

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/belgians-reach-deal-on-eu-canada-free-trade-agreement/article32542390/

- ↑ http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2017/september/tradoc_156062.pdf

- ↑ "Belgium green lights unchanged Ceta". https://euobserver.com/economic/135717.

- ↑ YorkRegion.com. "Trudeau Brussels-bound to sign CETA on Sunday". http://www.yorkregion.com/news-story/6934897-trudeau-brussels-bound-to-sign-ceta-on-sunday/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Bálint Péter Linder (2017-02-15). "CETA: MEPs back EU-Canada trade agreement". European Parliament Press Service. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/news-room/20170209IPR61728/ceta-meps-back-eu-canada-trade-agreement.

- ↑ Waldie, Paul (30 October 2016). "Trudeau signs CETA but final ratification still required by European Union". https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/national/prime-minister-trudeau-signs-canada-eu-trade-deal-in-brussels/article32586423/.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "BELGIAN REQUEST FOR AN OPINION FROM THE EUROPEAN COURT OF JUSTICE". Government of Belgium. https://diplomatie.belgium.be/sites/default/files/downloads/ceta_summary.pdf. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "THE MECHANISM FOR THE RESOLUTION OF DISPUTES BETWEEN INVESTORS AND STATES PROVIDED FOR BY THE FREE TRADE AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE EU AND CANADA (CETA) IS COMPATIBLE WITH EU LAW". Court of Justice of the EU. https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2019-04/cp190052en.pdf. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ↑ "What will the EU gain from CETA?". http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2016/february/tradoc_154331.pdf.

- ↑ SKREBLIN, Ksenija (20 September 2017). "Trgovinski sporazum između EU-a i Kanade stupa na snagu—Hrvatska—European Commission". https://ec.europa.eu/croatia/news/eu_canada_trade_agreement_enters_into_force_hr.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Sporazum o slobodnoj trgovini CETA—Gospodarstvo—DW—21.09.2017". http://www.dw.com/hr/sporazum-o-slobodnoj-trgovini-ceta/a-40623781.

- ↑ (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Gabriel optimistic over EU-Canada CETA trade deal | Business | DW.COM | 18.10.2016". http://www.dw.com/en/gabriel-optimistic-over-eu-canada-ceta-trade-deal/a-36073644.

- ↑ "EU Commission refuses to revise Canada Ceta trade deal" (in en-GB). BBC News. 2016-09-23. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-37450742.

- ↑ "Trading Away Democracy, HOW CETA'S INVESTOR PROTECTION RULES THREATEN THE PUBLIC GOOD IN CANADA AND THE EU". Published by Association Internationale de Techniciens, Experts et Chercheurs (Aitec), Vienna Chamber of Labour (AK Vienna), Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), Corporate Europe Observatory (CEO), Council of Canadians, Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), European Federation of Public Service Unions (EPSU), German NGO Forum on Environment & Development, Friends of the Earth Europe (FoEE), PowerShift, Quaker Council for European Affairs (QCEA), Quebec Network on Continental Integration (RQIC), Trade Justice Network, Transnational Institute (TNI), Transport & Environment (T&E).. November 2014. https://www.tni.org/files/download/ceta-isds-en_0.pdf.

- ↑ Blaise, Kerrie (30 Nov 2016). "Submissions to the Standing Committee on International Trade Re: An Act to Implement the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (Bill C-30)". Canadian Environmental Law Association. http://www.cela.ca/sites/cela.ca/files/1085-Standing%20Committee%20Submissions%20on%20CETA_Nov_30_2016.pdf.

- ↑ "CETA: As support softens, Canadians still back trade deal with Europe 5-to-1 over those who oppose it—Angus Reid Institute". 14 February 2017. http://angusreid.org/ceta-trudeau-europe/.

- ↑ "Facing tough talk over NAFTA renegotiations, Canadians rediscover affection for the trade pact—Angus Reid Institute". 12 February 2017. http://angusreid.org/trump-nafta-renegotiation/.

- ↑ Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (Canada), Assessing the Costs and Benefits of a Closer EU–Canada Economic Partnership, http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2008/october/tradoc_141032.pdf, retrieved 12 October 2016

- ↑ "Towards a Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement". European External Action Service. Archived from the original on 5 May 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150505112357/http://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/canada/eu_canada/trade_relation/ceta/index_en.htm. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ↑ Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (Canada), Canada–European Union Trade and Investment Enhancement Agreement, http://www.international.gc.ca/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/eu-ue/tiea.aspx?lang=en, retrieved 10 August 2010

- ↑ "Verhandlungen über Freihandelsabkommen mit Kanada abgeschlossen (Negotiations with Canada on freetrade agreement completed)". 2012-08-06. http://www.sueddeutsche.de/wirtschaft/entwurf-fuer-ceta-verhandlungen-ueber-freihandelsabkommen-mit-kanada-abgeschlossen-1.2078844. Retrieved 2012-08-06.

- ↑ ""Symbolic" summit to mark end of CETA talks". 2014-09-24. http://www.embassynews.ca/news/2014/09/24/%E2%80%98symbolic%E2%80%99-leaders%E2%80%99-summit-to-mark-the-end-of-ceta-talks/46100. Retrieved 2014-09-25.

- ↑ "Consolidated CETA Text". http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2014/september/tradoc_152806.pdf. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ↑ Laura Payton (2013-10-18). "CETA: Canada-EU free trade deal lauded by Harper, Barroso". CBC News. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/ceta-canada-eu-free-trade-deal-lauded-by-harper-barroso-1.2125122.

- ↑ "Canada-Europe deal risks derailment over visa spat". The Star (Toronto). https://www.thestar.com/business/2012/04/26/canadaeurope_trade_deal_risks_derailment_over_visa_spat.html.

- ↑ Kirpatrick, C.; Raihan, S., Bleser, A.; Prud’homme, D.; Mayrand, K.; Morin, JF.; Pollitt, H.; Hinjosa, L.; Williams, M. "EU–Canada SIA Final Report." September 2011, pp. 1–468

- ↑ "EU–Canada SIA Annexes to Final Report September 2011, pp. 1–106

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "EU–Canada SIA Briefing Document" September 2011, pp. 1–5

- ↑ "Gross domestic product at market prices". Eurostat. http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/tgm/refreshTableAction.do;jsessionid=9ea7d07d30df81d7d40a2e93409b986efd20d5e17291.e34MbxeSaxaSc40LbNiMbxeNaNaNe0?tab=table&plugin=1&pcode=tec00001&language=en. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2012/august/tradoc_149866.pdf

- ↑ "Canada–EU Trade Agreement Replicates ACTA's Notorious Copyright Provisions | Electronic Frontier Foundation". Eff.org. 21 July 2012. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2012/10/ceta-replicates-acta. Retrieved 2012-10-16.

- ↑ Rita Matulionyte (2 August 2018). "Future EU-Australia FTA and copyright: what could we expect in the IP chapter?". Kluwer Copyright Blog. http://copyrightblog.kluweriplaw.com/2018/08/02/future-eu-australia-fta-copyright-expect-ip-chapter/. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ↑ Geist, Michael (16 December 2009). "Beyond ACTA: Proposed EU – Canada Trade Agreement Intellectual Property Chapter Leaks". Michael Geist's Blog. Michael Geist. http://www.michaelgeist.ca/content/view/4627/125/. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ↑ Wyślij. "List 5 organizacji pozarządowych do Ministra Kultury i Ministra Gospodarki w sprawie umowy CETA :: Prawo kultury" (in pl). Prawokultury.pl. http://prawokultury.pl/newsy/list-5-organizacji-pozarzadowych-do-minstra-kultur/. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ↑ "Consolidated CETA Text". EUROPEAN COMMISSION, Directorate-General for Trade. 2014-08-05. https://www.tagesschau.de/wirtschaft/ceta-dokument-101.pdf. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ Government of Canada (2017). "CETA Chapter Summaries". https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/ceta-aecg/chapter_summary-resume_chapitre.aspx?lang=eng.

- ↑ Global Affairs Canada (2014). "Increasing exports of agricultural and agri-food products. In: Opening New Markets in Europe - Creating Jobs and Opportunities for Canadians. How CETA Will Benefit Canada's Key Economic Sectors.". pp. 7–8. https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/assets/pdfs/ceta-aecg/final_sectors_content-eng_v11.pdf.

- ↑ "Canada–European Union Economic and Trade Negotiations: The Agri-food Sector". Parliament of Canada. 2011. http://www.parl.gc.ca/content/lop/researchpublications/cei-25-e.htm?Param=ce5. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ↑ "CETA—EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement". Trade—European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/in-focus/ceta/#democracy.

- ↑ G+M: "Newfoundland and Labrador says talks at stalemate with Ottawa over fish fund", 26 May 2015

- ↑ "Bulgaria, Romania Tie EU-Canada Deal to Visas :: Balkan Insight". http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/bulgaria-romania-tie-eu-canada-deal-to-visa-free-travel-05-16-2016.

- ↑ all: Economia, a.s.. "Víza do Kanady brzy skončí | HN.IHNED.CZ - česko". Hn.Ihned.Cz. http://hn.ihned.cz/c1-60249600-viza-do-kanady-brzy-skonci. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ "Češi budou už brzy létat do Kanady opět bez víz — Domácí — ČT24 — Česká televize". Ceskatelevize.cz. 2013-07-15. http://www.ceskatelevize.cz/ct24/domaci/234748-cesi-budou-uz-brzy-letat-do-kanady-opet-bez-viz/. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ Canada, Government of (30 October 2016). "Canada News Centre - Search Results". cic.gc.ca. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/department/media/releases/2013/2013-11-14.asp.

- ↑ "Romania reaches visa deal with Canada: report" (in en-US). POLITICO. 2016-10-21. http://www.politico.eu/article/report-romania-reaches-visa-deal-with-canada/.

- ↑ "Bulgarian government approves signing of EU-Canada CETA deal". 2016-10-25. http://sofiaglobe.com/2016/10/25/bulgarian-government-approves-signing-of-eu-canada-ceta-deal/.

- ↑ Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (15 April 2015). "Electronic Travel Authorization (eTA)". https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/visit-canada/eta.html.

- ↑ Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (17 May 2013). "Entry requirements by country/territory". https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/services/visit-canada/entry-requirements-country.html#visaExempt.

- ↑ "US multinationals could sue EU governments through CETA" (in en-GB). https://www.euractiv.com/section/trade-society/news/us-multinationals-could-sue-eu-governments-through-ceta/.

- ↑ "Canada-EU Deal Likely to Result in 'Deluge' of Big Business Cases Brought Against European Governments". Common Dreams. http://www.commondreams.org/newswire/2016/09/19/canada-eu-deal-likely-result-deluge-big-business-cases-brought-against-european.

- ↑ "If you're worried about TTIP, then you need to know about CETA" (in en-GB). The Independent. 2015-09-29. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/if-youre-worried-about-ttip-then-you-need-to-know-about-ceta-a6671886.html.

- ↑ CETA: EU and Canada agree on new approach on investment in trade agreement, EU Commission Press Release, 29 February 2016

- ↑ "National ratification issue could derail EU-Canada trade deal". Financial Times. 3 July 2016. https://www.ft.com/content/8e9428d4-412a-11e6-9b66-0712b3873ae1.

- ↑ "The ratification of CETA by national parliaments – a stepping stone in the transition from the old world of trade towards the new world of international trade". EPP Group. 13 July 2016. http://www.eppgroup.eu/press-release/The-ratification-of-CETA-by-national-parliaments.

- ↑ "CETA: le vice-ministre canadien défend des "valeurs communes" devant le Parlement wallon". RTBF. 13 October 2016. https://www.rtbf.be/info/belgique/detail_ceta-le-vice-ministre-canadien-defend-des-valeurs-communes-devant-le-parlement-wallon?id=9428885.

- ↑ "Reynders heeft handtekening gezet onder Belgisch akkoord voor CETA". deredactie.be. 29 October 2016. http://deredactie.be/permalink/1.2805902.

- ↑ MOTION déposée en conclusion du débat sur l’Accord économique et commercial global (AECG–CETA). Doc. 633 (2016-2017) N° 3. P.W.—C.R.I. N° 6 (2016–2017)—Vendredi 28 octobre 2016.

- ↑ "EU and Canada sign CETA". European Commission. 30 October 2016. http://ec.europa.eu/news/2016/10/20161030_en.htm.

- ↑ "Notice concerning the provisional application of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) between Canada, of the one part, and the European Union and its Member States, of the other part". http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1515577599150&uri=CELEX:22017X0916(02).

- ↑ "C-30: An Act to implement the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between Canada and the European Union and its Member States and to provide for certain other measures". Parliament of Canada. http://www.parl.ca/LegisInfo/BillDetails.aspx?Language=E&billId=8549249. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ McGregor, Janyce (27 March 2017). "'We are ready': Canada-Europe trade deal set to kick in, mostly, by July 1". CBC News. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/ceta-implementation-malmstrom-canada-1.4039484. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ↑ McGregor, Janyce (2 July 2017). "Canada's trade deal with itself now in effect, as EU deal waits". CBC News. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/cfta-interprovincial-trade-july-1-1.4181380. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ↑ "Canada, EU to provisionally apply CETA in September". CBC News. 8 July 2017. http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/ceta-september-provisionally-1.4196210. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ↑ "Denmark is the second EU member-state to ratify CETA—Insights—DLA Piper Global Law Firm". https://www.dlapiper.com/en/denmark/insights/publications/2017/06/denmark-ratifies-ceta/.

- ↑ Garea, Fernando (29 June 2017). "El Congreso ratifica el CETA con críticas del PP y Ciudadanos al PSOE por su abstención". http://politica.elpais.com/politica/2017/06/29/actualidad/1498721488_698452.html.

- ↑ "Sabor potvrdio CETA-u". 30 June 2017. https://lider.media/aktualno/biznis-i-politika/hrvatska/sabor-potvrdio-ceta-u/.

- ↑ "Senate approves free trade deal with Canada". 20 April 2017. http://www.praguemonitor.com/2017/04/21/senate-approves-free-trade-deal-canada.

- ↑ "Lower house approves CETA agreement". 14 September 2017. http://praguemonitor.com/2017/09/14/lower-house-approves-ceta-agreement.

- ↑ "Governo aprova acordo comercial com o Canadá sem apoio dos parceiros". 20 September 2017. https://www.dn.pt/lusa/interior/governo-aprova-acordo-comercial-com-o-canada-sem-apoio-dos-parceiros-8784621.html.

- ↑ "Seimas ratifikavo Kanados ir ES prekybos susitarimą su specialiu pareiškimu". 24 April 2018. http://www.lrs.lt/sip/portal.show?p_r=119&p_k=1&p_t=257423.

- ↑ CBC News (23 July 2019). "French parliament narrowly ratifies CETA trade deal with Canada". CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/france-canada-ceta-trade-deal-1.5221766. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ↑ Nationale, Assemblée. "Ratification du CETA : adoption par scrutin public le 23 juillet" (in fr-FR). http://www.assemblee-nationale.fr/dyn/actualites-accueil-hub/ratification-du-ceta-adoption-par-scrutin-public-le-23-juillet.

- ↑ a.s, Petit Press (2019-09-26). "Parliament approves trade agreement with Canada" (in en). https://spectator.sme.sk/c/22222080/parliament-approves-trade-agreement-with-canada.html.

- ↑ "Ceta ratification approved despite protests - Delano - Luxembourg in English" (in fr). 2020-05-07. http://delano.lu/d/detail/news/ceta-ratification-approved-despite-protests/210383.

- ↑ Bernhard Kempen (2016-08-29). "Beschwerdeschrift zur Bürgerklage "Nein zu CETA"" (in de) (PDF). mehr-demokratie.de. https://www.mehr-demokratie.de/fileadmin/pdf/2016-08-30_CETA-Klage.pdf.

- ↑ "Bundesverfassungsgericht - Presse - Eilanträge in Sachen "CETA" erfolglos" (in de). 2019-09-26. https://www.bundesverfassungsgericht.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/DE/2016/bvg16-071.html.

- ↑ "Kurzinformation Organstreitverfahren zum CETA-Abkommen vor dem Bundesverfassungsgericht - Deutscher Bundestag" (in de). 2018-03-18. https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/556774/9a924b1f985684c9b3edad20fc239060/WD-3-079-18-pdf-data.pdf.

External links

- Comprehensive economic and trade agreement (CETA) between the EU and Canada

- Annexes to the comprehensive economic and trade agreement (CETA) between the EU and Canada

- Trading Away Democracy, How CETA's investor protection rules threaten the public good in Canada and the EU, November 2014 White paper from the Transnational Institute (TNI)

- Official EU CETA site

- Market Access Map (A free tool developed by International Trade Centre, which identify customs tariffs, tariff rate quotas, trade remedies, regulatory requirements and preferential regimes applicable to products, including Hong Kong–New Zealand CEPA)

- Rules of Origin Facilitator (A free tool jointly developed by International Trade Centre, World Trade Organization and World Customs Organization which enables traders to find specific criteria and general origin requirements applicable to their products, understand and comply with them in order to be eligible for preferential tariffs. The tool is very useful for traders who want to gain benefit from Hong Kong–New Zealand CEPA)

KSF

KSF